- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

11

Urinary Tract

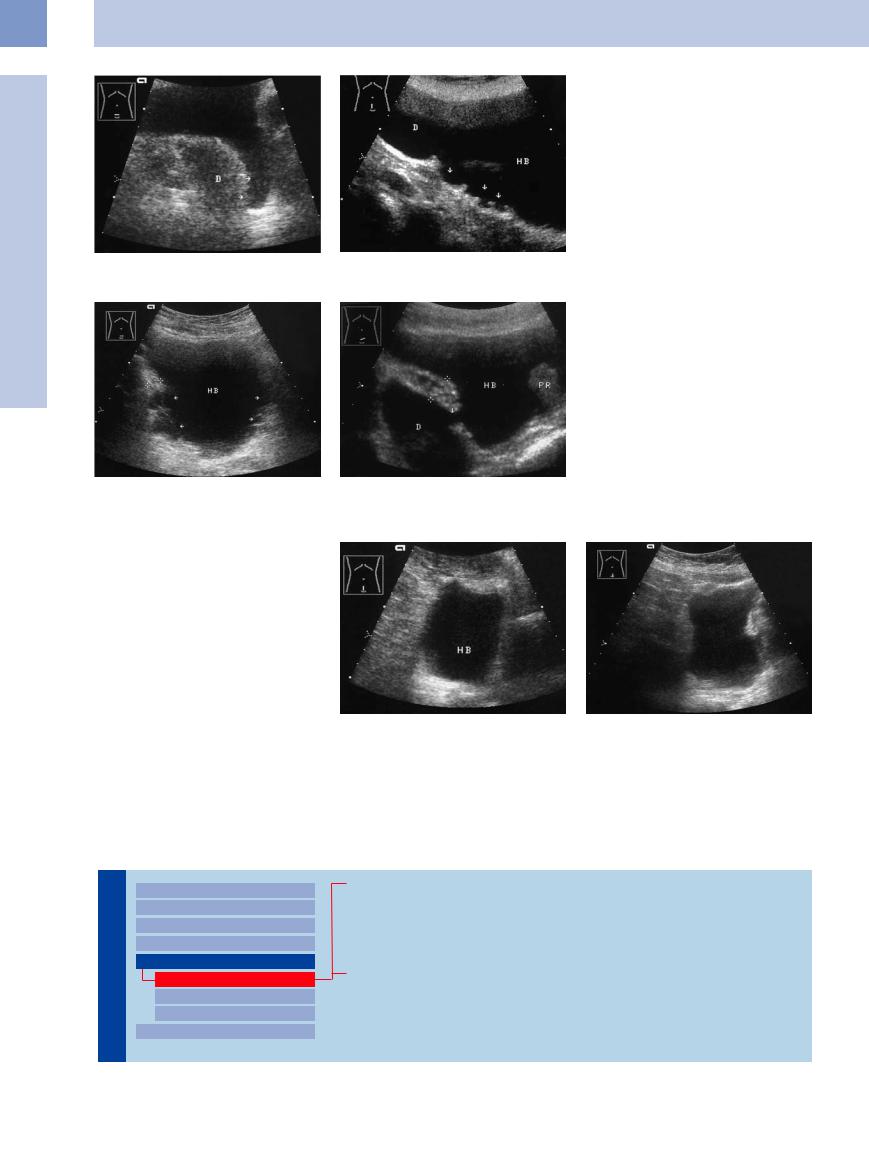

Fig. 11.62 Bladder diverticulum in a partially filled bladder.

a With additional distension a hypoechoic saccular mass appears, representing a large, partially filled diverticulum

(D). The extension (arrows) corresponds to the elongated neck of the diverticulum.

b Primary diverticula cranially (D) and on the bladder floor (arrows). Female, additional ectopic ureteral insertion and reflux (see Fig. 11.29).

Fig. 11.63

a Multiple pseudodiverticula (arrows) with wall hypertrophy (cursors). The protrusion of the diverticula through gaps in the bladder wall can be seen. HB = bladder.

b Large pseudodiverticulum (D), neck of diverticulum (arrow), and wall hypertrophy (12.8 mm) in benign protuberant prostatic hyperplasia (PR).

Indented Bladder,

Bladder,  Operated Bladder

Operated Bladder

Bladder shape can also be altered by extrinsic indentation from a tumor, an enlarged uterus, colonic gas, or adherent bowel loops.

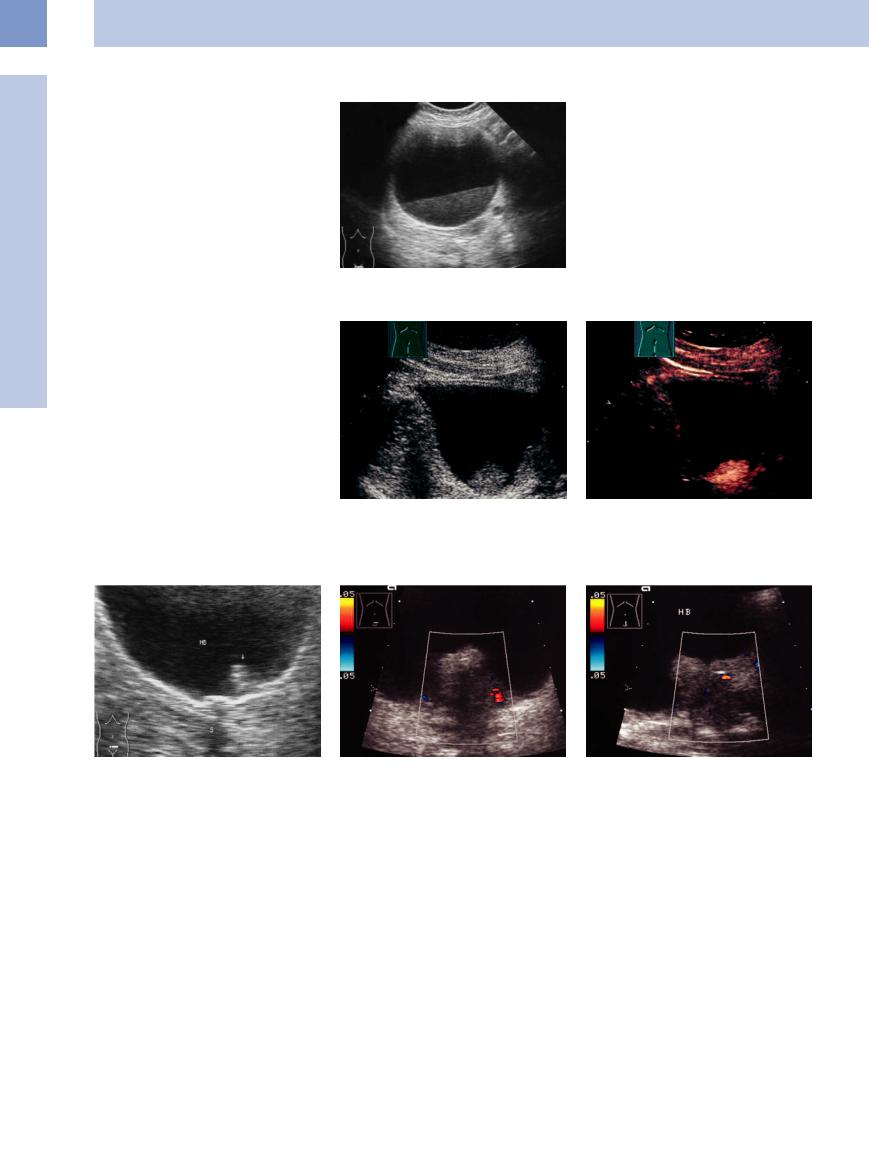

A special case is a bladder substitute that has been reconstructed from bowel. The ileal neobladder resembles a normal full bladder but is distinguished by its asymmetry and thin wall (Fig.11.64, Fig.11.65).

Fig. 11.64 Scarring and deformity of the bladder (HB) caused by old peritonitis following severe colitis and colostomy placement. Polygonal bladder shape with tapered extensions and ill-defined walls.

Fig. 11.65 Ileal bladder substitute following bladder tumor surgery. The substitute bladder has an irregular shape and no clearly defined wall (the ileal wall is not visualized in the standard 3.5 MHz scan).

■ Intracavitary Mass

Hypoechoic

Tract |

|

Malformations |

|

|

|

|

|

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter |

|

|

|

|

|

Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass |

Urinary |

|

|

|

Changes in Bladder Size or Shape |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intracavitary Mass |

|

|

|

|

|

Hypoechoic |

|

|

Hyperechoic |

|

|

Echogenic |

|

|

Wall Changes |

|

|

Blood Clots

Bladder Sludge

Bladder Papilloma

Polypoid Bladder Carcinoma

Mesenchymal Tumors

402

Blood Clots

Blood clots in the bladder are usually iatrogenic following the construction of a suprapubic bladder fistula, but they can also result from inflammations, cytostatic therapy, coagulation disorders, and tumors. If they are mobile, the diagnosis is easily made. But clots adherent to the bladder wall require differentiation from polypoid tumors, which they resemble in their mixed hypoechoic–hyperechoic structure. This differentiation can be made by demonstrating

their mobility and possible shape changes when the patient is repositioned or by instilling fluid into the bladder through an indwelling catheter. Tumors are distinguishable from blood clots by their vascularity in contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS; Fig.11.66, Fig.11.67).

Bladder tamponade. Bladder tamponade is caused by extremely heavy clot formation, leading to severe compression pain and com-

pletely obstructing the outflow of urine. Generally it requires operative treatment. Sonographically, bladder tamponade appears as a tumor-like mass, usually slightly heterogeneous to hypoechoic, that completely occupies the bladder lumen. Residual anechoic urine is sometimes detectable (Fig.11.68, Fig.11.69).

11

Intracavitary Mass

Fig. 11.66 Clotted blood in the bladder (HB), lower abdominal transverse scan.

a Tumor-like echo texture (arrow).

b The mass is no longer seen after several position changes, proving that it is not a real tumor. Its position also changes on standing. Other ways to distinguish a clot from tumor are to repeat the scans with different degrees of bladder distention or rapidly fill the bladder through an indwelling catheter.

Fig. 11.67 Large polypoid blood clot (arrow), appearing as an echogenic mass on the bladder floor. The clot showed motion-dependent shape and position changes with transient swirling of clot particles. HB = bladder.

Fig. 11.68 Incomplete bladder tamponade.

a Bizarre, tumor-like hypoechoic mass (arrow) with a small amount of residual free urine.

b The clot moved after several position changes, excluding a tumor. HB = bladder.

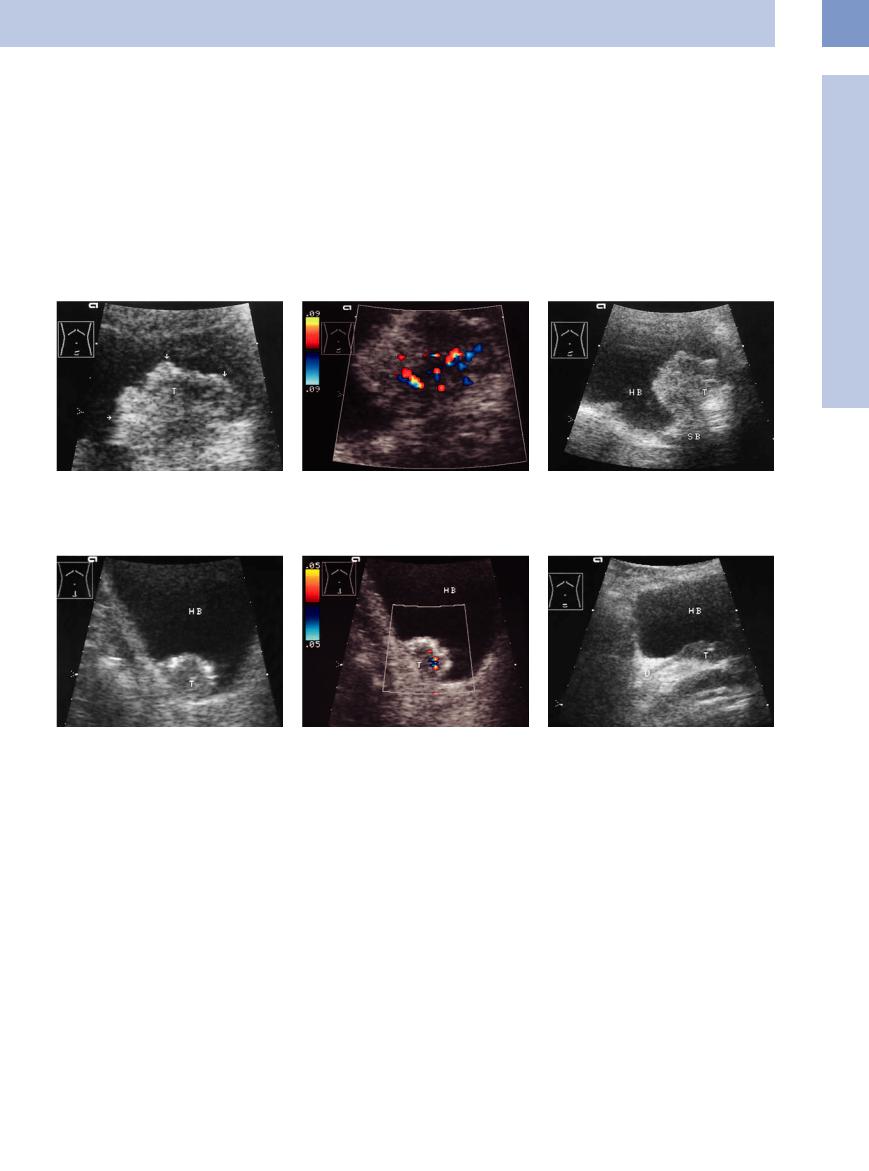

Fig. 11.69

a Bladder tamponade requiring surgery. The bladder is filled by hypoechoic clot with a nonhomogeneous structure.

b Differential diagnosis of bladder tamponade. The bladder (HB) has been invaded by sigmoid carcinoma (T), which completely fills the bladder lumen.

403

11

Urinary Tract

Bladder Sludge

Sediment found in the bladder usually consists of urinary precipitates or pus. It presents a shifting or mobile sludge structure much like that seen in the gallbladder. The mobility of bladder sludge will generally distinguish it from flat, sessile bladder-wall tumors and areas of hypertrophic wall thickening. The best diagnostic procedure may be CEUS (Fig.11.70).

Fig. 11.70 Purulent bladder sediment in a patient with pyonephrosis.

Bladder Papilloma

Most benign and malignant bladder tumors appear sonographically as exophytic intraluminal masses or as plaque-like lesions infiltrating the bladder wall. Benign bladder papilloma is an example of an exophytic tumor. Other than the loose correlation between tumor size and biological behavior, there are no sonographic criteria that can confidently distinguish a benign papilloma from papillary carcinoma. Detectable wall infiltration is suggestive of carcinoma, however. This requires differentiation from an adenoma of the prostatic median lobe protruding into the bladder (Figs. 11.71, 11.72, 11.73).

Fig. 11.72 Bladder papilloma (arrow): lobulated, narrow polypoid mass occupying a constant position in the bladder. Next to it is a hyperechoic mass with an acoustic shadow (S): bladder stone. HB = bladder.

Fig. 11.71 a and b Polypoid bladder tumor (images courtesy of Professor C. Goerg, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Marburg, Germany).

a Gray-scale image: lobulated hypoechoic mass on the bladder floor.

Fig. 11.73 Median-lobe adenoma (benign prostatic hyperplasia), color Doppler.

a Polypoid mass extending into the bladder lumen. Apparent wall infiltration, scant peripheral vascularity.

b CEUS: intensive enhancement (arrow): bladder tumor.

b Longitudinal scan angled slightly downward shows that the tumor is connected to the median lobe of the prostate. HB = bladder.

Polypoid Bladder Carcinoma

Bladder Carcinoma

Most benign and malignant bladder tumors arise from the transitional epithelium (urothelium). Other tumor types include squamous cell carcinomas (often associated with schistosomiasis), adenocarcinomas, and mesenchymal tumors (rhabdomyosarcoma, seen mainly in children). The Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) staging system is shown in Fig.11.98, p. 412. The most common malignant bladder tumor is urothelial carcinoma. Morphologically, approximately 70% of malignant bladder tumors display a papillary, almost villous type of growth. A small percentage are

solid or nodular. Bladder carcinomas metastasize chiefly to the regional lymph nodes along the iliac vessels. They can also seed hematogenously to the liver, lung, and bone marrow.

Bladder carcinomas may become ulcerated, and therefore typical complaints such as urgency are usually accompanied by hematuria.

Sonographic features. Polypoid bladder carcinoma is easily detected sonographically in a well-distended bladder when the lesion is larger than 5 mm. Exceptions are tumors located on the floor or roof of the bladder. Ultra-

sound demonstrates a nonhomogeneous internal echo pattern with smooth or lobulated, often hyperechoic, margins (Fig.11.74, Fig.11.75). Some tumors are pedunculated and exhibit a cauliflower-like structure. An intensely echogenic “hood” suggests a fibrous or partially calcified tumor surface, which is reportedly more characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma.9 The sonographic staging10 of a presumed or detected bladder carcinoma requires evaluating the deeper wall structures.

404

Sensitivity of ultrasound. Ultrasound has only about a 50% sensitivity in the diagnosis of bladder tumors.11 This results from the low detection rate of small tumors and precancerous lesions confined to the mucosa, tumors located on the bladder roof or anterior wall, and multiple tumors. Other lesions that usually escape sonographic detection are foci of simple or atypical hyperplasia, small urothelial papillomas, carcinoma in situ, plaque-like urothelial carcinomas, and small papillary carcinomas. Wall infiltration (mucous layer, infiltration into the muscle layer) is not detectable in abdominal ultrasound.

Fig. 11.74 Polypoid bladder tumor (T; papillary urothelial carcinoma).

a Intravesical mass with irregular margins (blooming effect causes the surface to appear more echogenic).

Fig. 11.75 Polypoid bladder tumor (T). Histology (after transurethral resection) indicated urothelial carcinoma without bladder wall infiltration (stage pTa).

a Hypoechoic tumor with an echogenic rim and no detectable bladder wall infiltration. HB = bladder.

Differentiation from clot. It is difficult to distinguish bladder carcinoma from intravesical clots. The following criteria are helpful in this regard:

●A mass on the bladder roof or side walls is suggestive of neoplasia.

●Movement of the mass when the patient is repositioned suggests a clot (no movement is more consistent with a neoplasm).

●Swirling echoes and a change in shape and size on rapid filling of the bladder suggest a blood clot.

b Irregular tumor vessels are detected, proving that the mass is not a clot.

b Color Doppler shows spotty vascularity.

●Color Doppler examination: vascularity suggests a tumor, while lack of vascularity (low flow velocity) is more consistent with a clot.

●Wall infiltration positively identifies the mass as a tumor.

●Repeat scans should always be obtained to check the constancy of the finding.

A bladder tumor is rarely the result of invasion by prostatic carcinoma, because that tumor arises from the outer zone of the prostate and does not extend toward the bladder floor like a median-lobe adenoma (Fig.11.76).

c Infiltration of the seminal vesicle (SB) is detected, indicating a stage T4a tumor by ultrasound (see Fig. 11.98).

Fig. 11.76 Known local metastatic prostatic carcinoma, histologically confirmed. The tumor (T) has infiltrated the bladder floor and obstructed the ureter (U). The tumor regressed completely after combined hormonal and chemotherapy. HB = bladder.

Mesenchymal Tumors

Reticuloendothelial tumors and the rare mesenchymal tumors rhabdomyoma and rhabdomyosarcoma are sonographically indistinguishable from urothelial carcinoma, and so the same ultrasound criteria are used for these tumors as for carcinoma.

11

Intracavitary Mass

405