- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

2

Liver

Round Ligament of the

of the  Liver

Liver

In cross-sectional views of the upper quadrants, the round ligament will appear usually as a more or less hyperechoic lesion ( 2.12h,i). The decisive aspect for differentiating this spherical hyperechoic lesion from a true mass is scanning in the sagittal plane, and its characteristic location between segments II and III on the left and segment IV on the right.

2.12h,i). The decisive aspect for differentiating this spherical hyperechoic lesion from a true mass is scanning in the sagittal plane, and its characteristic location between segments II and III on the left and segment IV on the right.

Anatomy of the Round Ligament

The round ligament (ligamentum teres) is a fibrous septum separating the double segments II/III medially on the left from the double segments IVa/IVb laterally on the right, thus splitting the liver into the anatomic left and right lobes. The obliterated umbilical vein ascends in this fibrous cord from the umbilicus to end in the left branch of the portal vein. In portal hypertension,

varicose collaterals are opened up along the obliterated umbilical vein (which may become patent again), shunting blood from the portal venous system of the liver to the convoluted cutaneous varicosities around the umbilicus (caput medusae) (see also recanalized umbilical vein (inner and outer caput medusae)  1.8 g–l).

1.8 g–l).

Focal Fatty Change

Change

Increased fatty infiltration in individual seg- |

preservation of segmental interfaces, and |

outline. The kinetics of the contrast agent in |

ments or certain areas of the liver parenchyma |

course of vessels usually points the way toward |

infiltrated parenchyma does not differ from |

may mimic an echogenic mass. The lack of |

diagnosing this parenchymatous lesion as focal |

that of the normal liver parenchyma in CEUS. |

texture-induced changes in the surface, the |

fatty change. These changes have a map-like |

|

Bile Ducts/Vessels

Dilated bile ducts may be filled with sediment, sludge, or viscous bile. Past thrombosis of the portal vein may appear as mass of moderate echogenicity.

Echogenic Masses

|

|

|

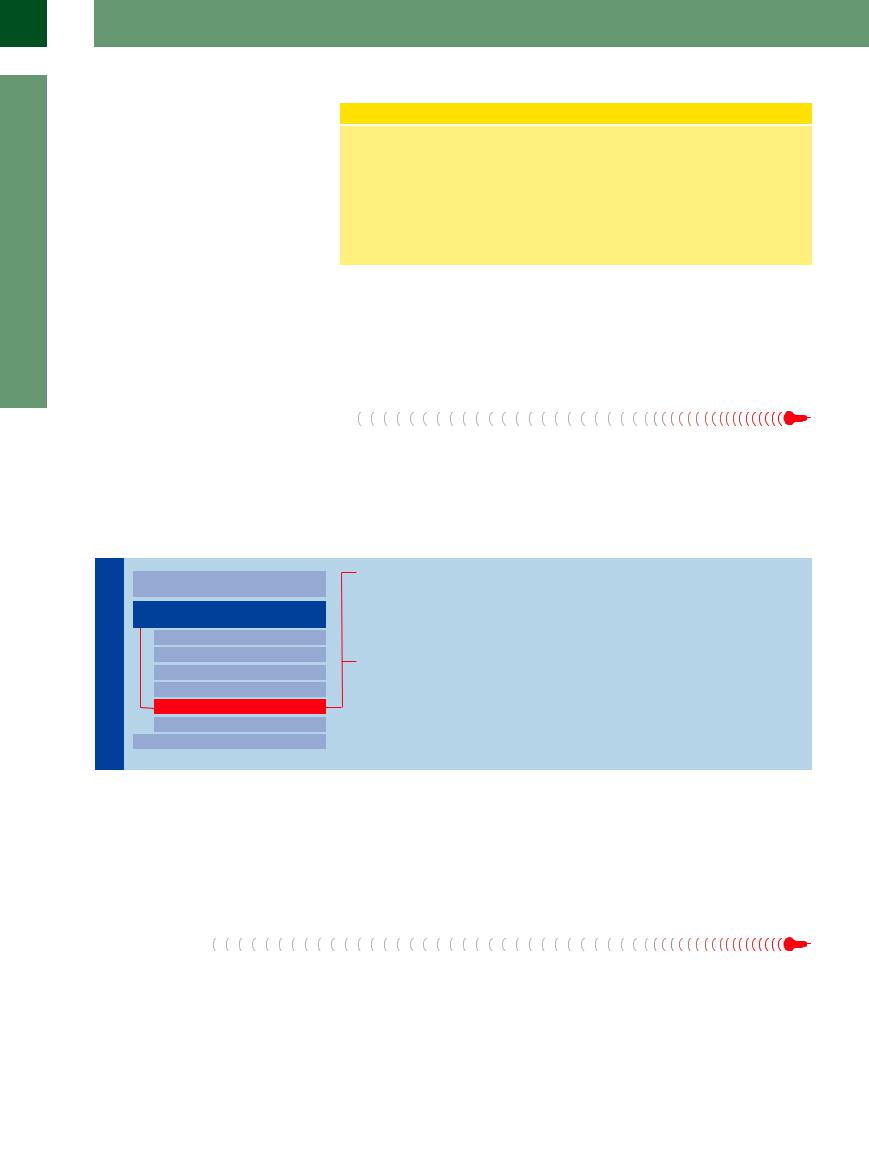

Diffuse Changes in Hepatic |

|

Liver |

Parenchyma |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Localized Changes in Hepatic |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Parenchyma |

|

|

|

|

|

Anechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hypoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Isoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hyperechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Echogenic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Irregular Masses |

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions |

|

|

|

|

||

“Comet Tails”

Calcification

Calculus

Foreign Body

Air

The echogenic appearance of a mass in the liver is due to changes that result in total reflection of the signal, complete absorption of the ultrasound energy, and in consequence posterior shadowing. Since in many cases the texture of the mass itself cannot be evaluated, any further differentiation has to rely on the type of shadowing encountered.

“Comet Tails”

Very small but powerful reflectors produce impressive artifacts likened to the tail of a comet. The most frequent location of the reflectors is periportal, but they may also be found within

the parenchyma. By themselves, the reflectors are hard to detect and differentiate, but their comet tails, which sparkle in real-time studies, make them hard to miss (Fig. 2.100, Fig. 2.101).

These impressive comet-tail artifacts are the sequelae of changes induced by inflammation of the liver or bile ducts, which can present themselves as fine calcification (Fig. 2.102).

114

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

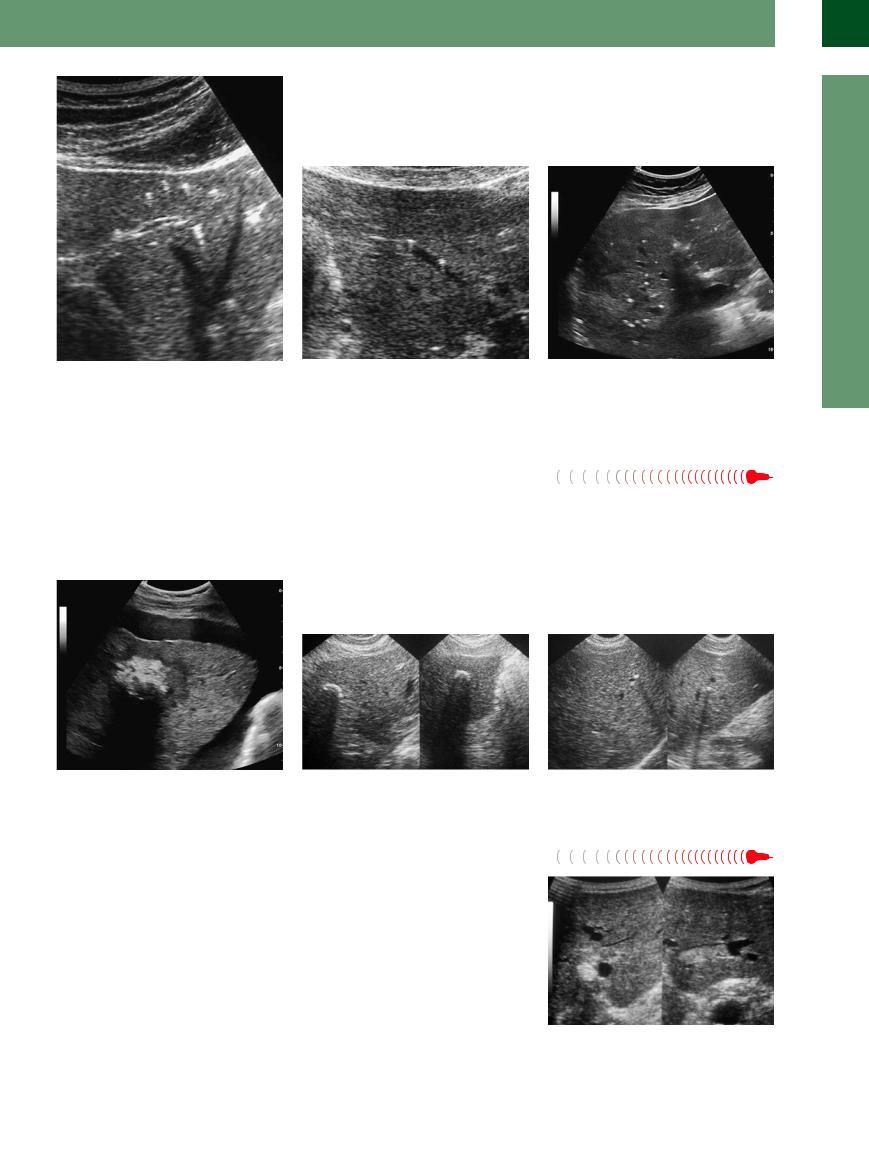

Fig. 2.100 These coarse reflectors within the hepatic pa- |

Fig. 2.101 “Comet tails.” Coarse perivenous reflectors; |

renchyma, characterized by their strong intrinsic echo |

note the characteristic posterior reverberation artifacts. |

and the posterior reverberation artifacts, are known as |

|

“comet tails.” |

|

Calcification

Calcifications present as echogenic masses that, |

even within hepatic masses. The calcifications |

|

depending on their size, will always lead |

to |

in hydatid cysts, hepatocellular carcinoma, and |

posterior shadowing. They may be found |

in |

metastases (Figs. 2.103, 2.104, 2.105) are typi- |

the parenchyma, around the portal veins, and |

cal examples. Differential diagnosis of echo- |

|

Fig. 2.103 Necrotic and calcified metastasis in a colonic |

Fig. 2.104 Calcification in an old Echinococcus infection. |

carcinoma after several years of palliative chemotherapy. |

|

Calculus

Gallstones in the intrahepatic bile ducts are a |

changes are limited to individual segments of |

||

characteristic finding |

in Caroli |

disease |

the liver, in which case these echodense masses |

(Fig. 2.106, Fig. 2.107). They may obstruct the |

are grouped like beads on a string. To confirm |

||

duct completely and thus mimic an intrahe- |

the suspected diagnosis, the sonographer has |

||

patic echodense mass. |

Frequently, |

these |

to pinpoint a fluid-filled/congested bile duct. |

Fig. 2.102 Postinflammatory periportal and parenchymatous microcalcification.

dense periportal masses has to include the possibility of calculi in the intrahepatic bile ducts as well as phleboliths in branches of the portal vein.

Fig. 2.105 Small periportal calcification.

Fig. 2.106 Sediments in the bile duct.

115

2

Liver

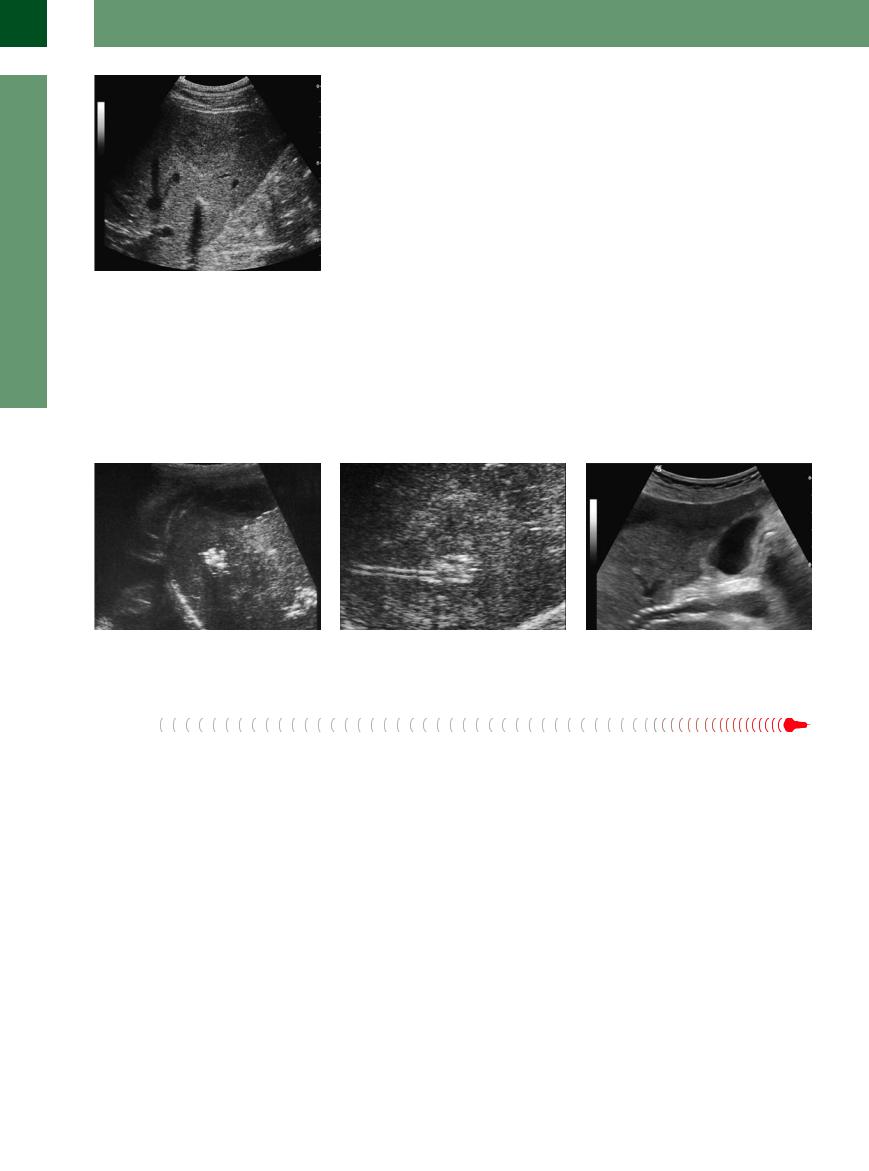

Fig. 2.107 Calculus within a bile duct (in Caroli disease); ventrally, demonstration of an atypical isoechogenic hemangioma (CEUS).

Foreign Body

Because of their typical texture and the pa- |

splinters and projectiles will also be imaged |

leak) or hyperechoic repair areas with organ- |

tient’s history, iatrogenic foreign bodies in the |

as echodense masses with posterior shadow- |

ization/granulation and the formation of scar/ |

liver (drains, stents, clips) are relatively easily |

ing. Depending on the time since they pene- |

fibrous tissue. |

detected as echodense hepatic masses of vary- |

trated the liver, they may be surrounded by |

|

ing shape (Figs. 2.108, 2.109, 2.110). Metallic |

hypoechoic liquid lesions (hemorrhage, biliary |

|

Fig. 2.108 Foreign body—here the basket of an abscess drain.

Air

Gas will produce hyperechoic reflections, and sometimes even brilliant sparkles. There is an eminent difference between the sonographic appearance of small individual gas bubbles and large areas containing gas. The latter result in the characteristic total reflection and poste-

Fig. 2.109 Foreign body—here abscess drain with basket.

rior shadowing with its ill-defined margin, while small individual bubbles will not generate posterior shadowing. The acoustic stimulation triggers natural oscillation, which in turn produces an ill-defined posterior tail, a hum, and may therefore be identified by real-time

Fig. 2.110 Foreign body—transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).

scanning. Gas pockets can be found in bile ducts and portal vein branches or they may be part of complications within a hepatic mass (tumor, metastasis, abscess) ( 2.13).

2.13).

116

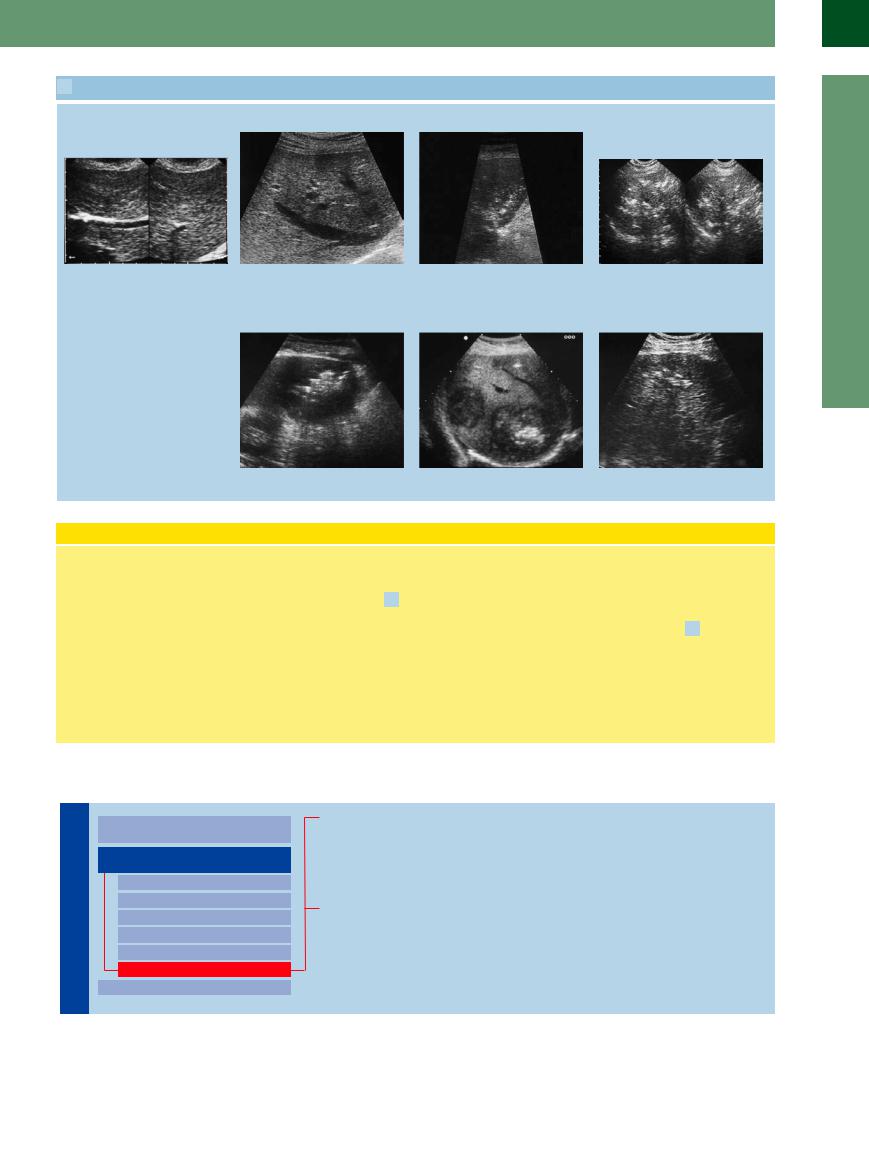

2.13 Intrahepatic Accumulation of Gas

2.13 Intrahepatic Accumulation of Gas

Pneumobilia. Gas formation

a Pneumobilia: periportal echoes. |

b Periportal echoes in discrete pneumo- |

|

bilia after Whipple procedure; no comet |

|

tails. |

e Abscess with central necrosis and gas formation.

c Portovenous gas embolism. Left: Early stage with initial gas deposits in the parenchyma. Right: Late stage with advanced confluent accumulation of gas in the parenchyma.

f Necrosis after percutaneous ethanol injection, with gas formation in HCC.

d Late stage of confluent gas formation.

g Necrosis with gas formation in HCC, after transarterial chemoembolization.

Intrahepatic Accumulation of Gas

Any accumulation of gas detected in the liver has to be regarded as a serious complication unless it is due to iatrogenic intervention.

Mass. Gas accumulated in a mass points to an infection with gas-forming bacteria, usually Gram-negative pathogens; another alternative would be necrosis with or without complications.

Diffuse. Diffusely distributed gas in the hepatic parenchyma is found in portovenous gas embolism, initially as coarse periportal echoes ( 2.13 d–g). Real-time ultrasound scanning can demonstrate gas bubbles being swept into the liver via the portal vein. If the barrier between the intestinal lumen and the mesenteric vascular system is impaired as a result of necrotic inflammation or ulcers, or because of endoscopic/radiological procedures, the result may be this potentially life-threatening pathological finding.

2.13 d–g). Real-time ultrasound scanning can demonstrate gas bubbles being swept into the liver via the portal vein. If the barrier between the intestinal lumen and the mesenteric vascular system is impaired as a result of necrotic inflammation or ulcers, or because of endoscopic/radiological procedures, the result may be this potentially life-threatening pathological finding.

Aerobilia. In the case of portovenous gas embolism, the detection of immobile sessile echoes in the hepatic parenchyma and the hepatopetal flow of gas bubbles within the portal vein rules out the differential diagnosis of pneumobilia ( 2.13a,b). In the latter case, the air in the bile ducts will shift, and when the patient is repositioned the gas will accumulate at the highest point; the acoustic energy may induce reverberation in the gas, making it “hum.”

2.13a,b). In the latter case, the air in the bile ducts will shift, and when the patient is repositioned the gas will accumulate at the highest point; the acoustic energy may induce reverberation in the gas, making it “hum.”

Irregular Masses

|

|

|

Diffuse Changes in Hepatic |

|

Liver |

Parenchyma |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Localized Changes in Hepatic |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Parenchyma |

|

|

|

|

|

Anechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hypoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Isoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hyperechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Echogenic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Irregular Masses |

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions |

|

|

|

|

||

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Thorotrastosis

Diffuse Metastasis

Alveolar Hydatid Disease

Liver Injuries in Multiple Trauma

The texture of the hepatic parenchyma can be |

one or more of the characteristics of the indi- |

inferred from the size, density, brilliance, and |

vidual echo. If hepatic lesions are distributed |

distribution/pattern of the individual echoes. |

more or less evenly and affect the entire organ, |

Textural irregularities result from changes in |

they may be very hard to detect as circum- |

scribed lesions or at all. The following entities are characterized by precisely such textural changes.

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

117

2

Liver

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Carcinoma

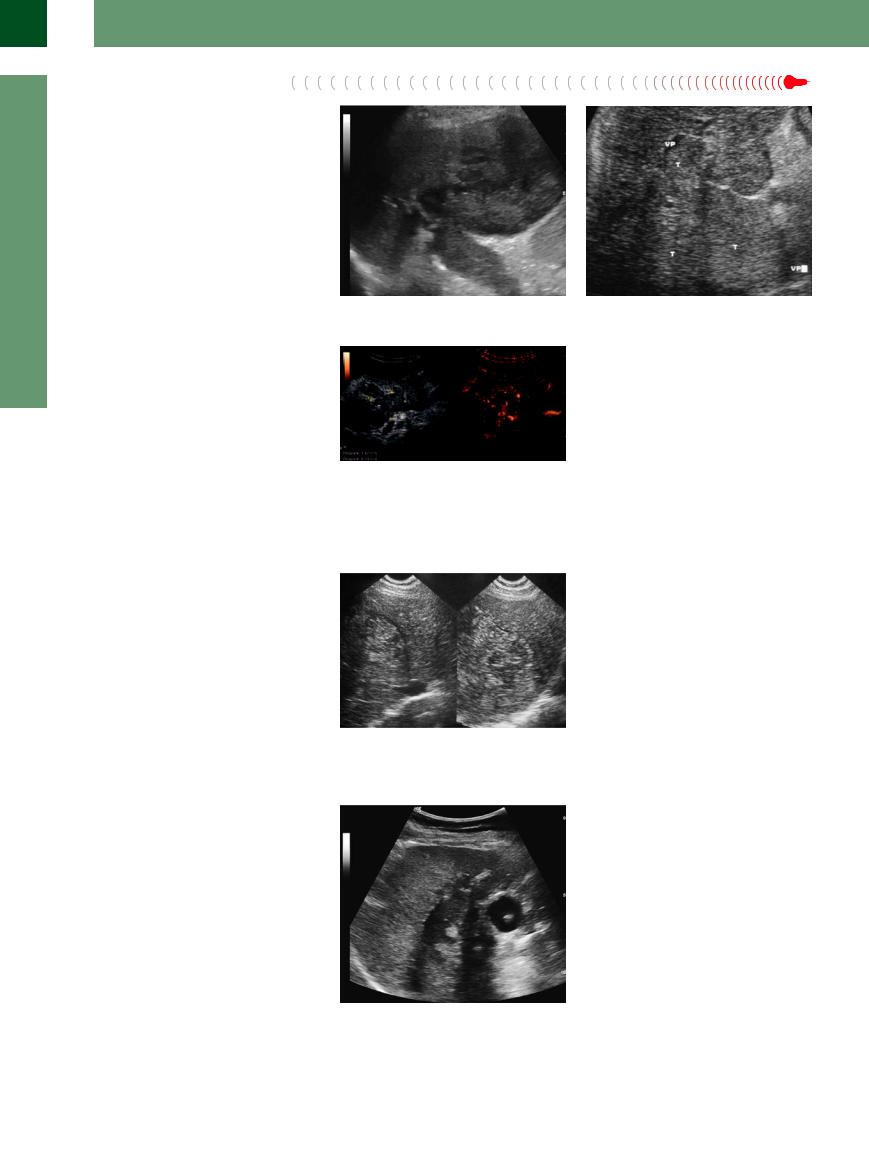

Diffuse HCC cannot be differentiated from the coarse echotexture of cirrhosis. Telltale signs of malignancy are typical complications of HCC, such as invasion of the vascular system, and the diffuse irregular hypervascularization that may be demonstrated on color-flow Doppler imaging or by CEUS (Figs. 2.111, 2.112, 2.113;

2.10 d, m–s).

2.10 d, m–s).

Fig. 2.111 Diffuse HCC with portal vein thrombosis.

Fig. 2.113 HCC with diffuse invasion of the portal vein; tumor vascularization of the thrombus (CEUS, arterial phase).

Fig. 2.112 HCC with diffuse invasion of the portal vein (VP). T = tumor.

Thorotrastosis

This tumor is hardly ever seen now and is also |

Fig. 2.114 Thorotrastosis. |

characterized by diffuse changes of the entire |

|

hepatic parenchyma (Fig. 2.114). |

|

Diffuse Metastasis

Although diffuse metastasis of the liver may |

Fig. 2.115 Diffuse infiltration into the liver in gallbladder |

|

involve the entire organ, it may be impossible |

carcinoma; an inflammatory infiltration can be excluded; |

|

to delineate individual lesions as metastases |

extent and dimensions can be demonstrated by CEUS |

|

(see Fig. 3.64 d,e, Chapter 3). |

||

with any certainty. Such changes are quite fre- |

||

|

||

quent in cancer of the breast, stomach, and |

|

|

pancreas (Fig. 2.115). CEUS is indispensable |

|

|

for diagnostic clarification. |

|

118