- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

13

Female Genital Tract

Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

Female Genital Tract

Vagina

Uterus Fallopian Tubes Ovaries

Anechoic Cystic Mass

Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

Endometriotic Cysts

Thecomatosis

Inflammatory Adnexal Mass

Ovarian Carcinoma

Metastases

Pseudomyxoma Peritonei

Ovarian Tumors (by Histological Criteria)

Endometriotic Cysts

Cysts

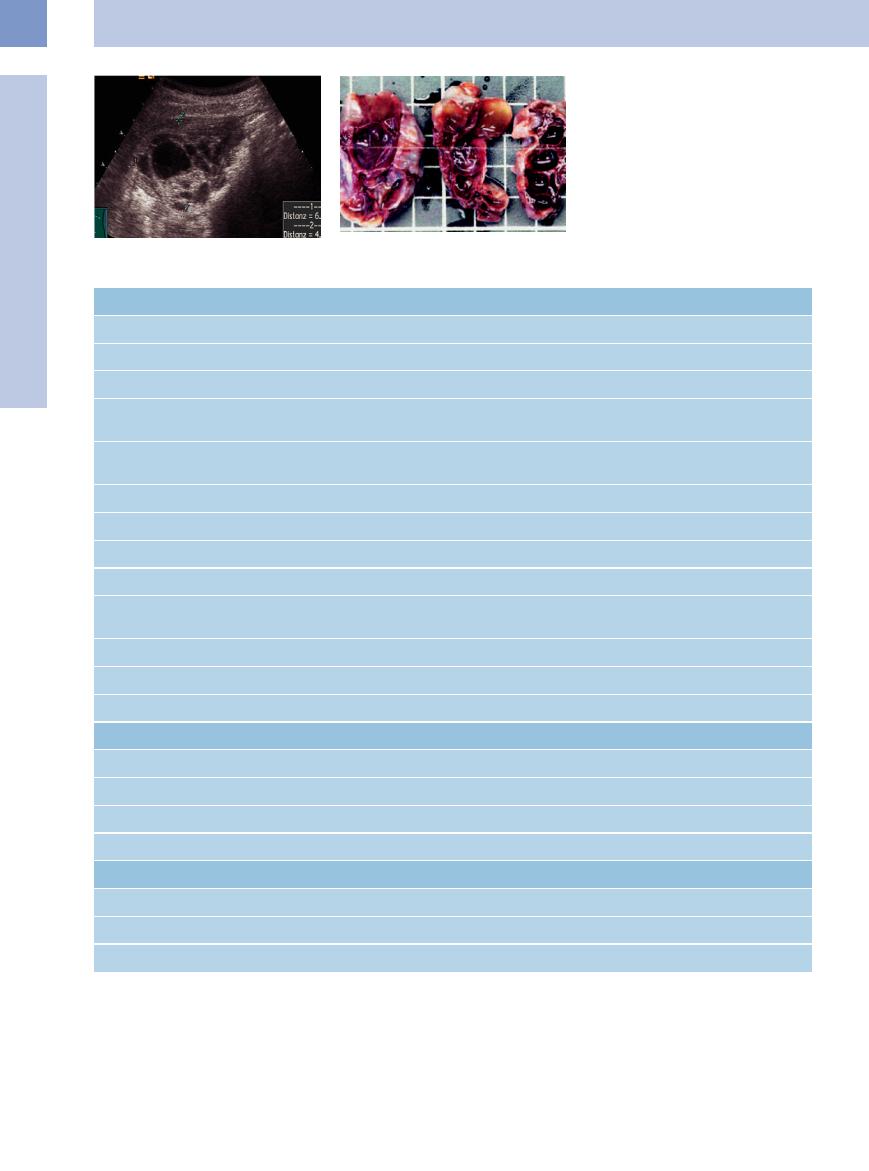

Fifty-five percent of patients with endometriosis have ovarian involvement. The endometriotic cysts are usually located on the ovarian surface, initially have a uniformly hypoechoic cystic appearance, and later become nonhomogeneous owing to recurrent bleeding. In this case the endometriosis is no longer distin-

Table 13.2 Differential diagnosis of endometriotic cysts

●Hemorrhagic functional cyst

●Cystadenoma

●Ovarian carcinoma (endometrioid carcinoma)

●Intraligamentous myomas

●Inflammatory processes

guishable from carcinoma. The full differential diagnosis is shown in Table 13.2.

The sonographic criteria are as follows (Figs. 13.96, 13.97, 13.98):

●Anechoic mass on the cortex, 1–5 mm in diameter

Ovarian Endometriosis

Pathogenesis. The cyst wall is lined with endometrioid epithelium. This can result from the dissemination of endometrium from the uterus, but a more likely cause is the primary formation of cysts composed of celomic epithelium. This would better explain the primary occurrence of ovarian adenocarcinoma (approximately 5% of ovarian tumors are endometrioid tumors, mostly carcinomas).

●With intracystic bleeding, the mass enlarges and may show homogeneous internal echoes

●Thick, echogenic wall

●Difficult to localize to a specific organ

●With recurrence, a nonhomogeneous echo pattern may be seen

Management. Histological confirmation is always required. Ultrasound follow-ups should be scheduled at 6-month intervals. Response should be monitored in cases that have been treated with GnRH analogues.

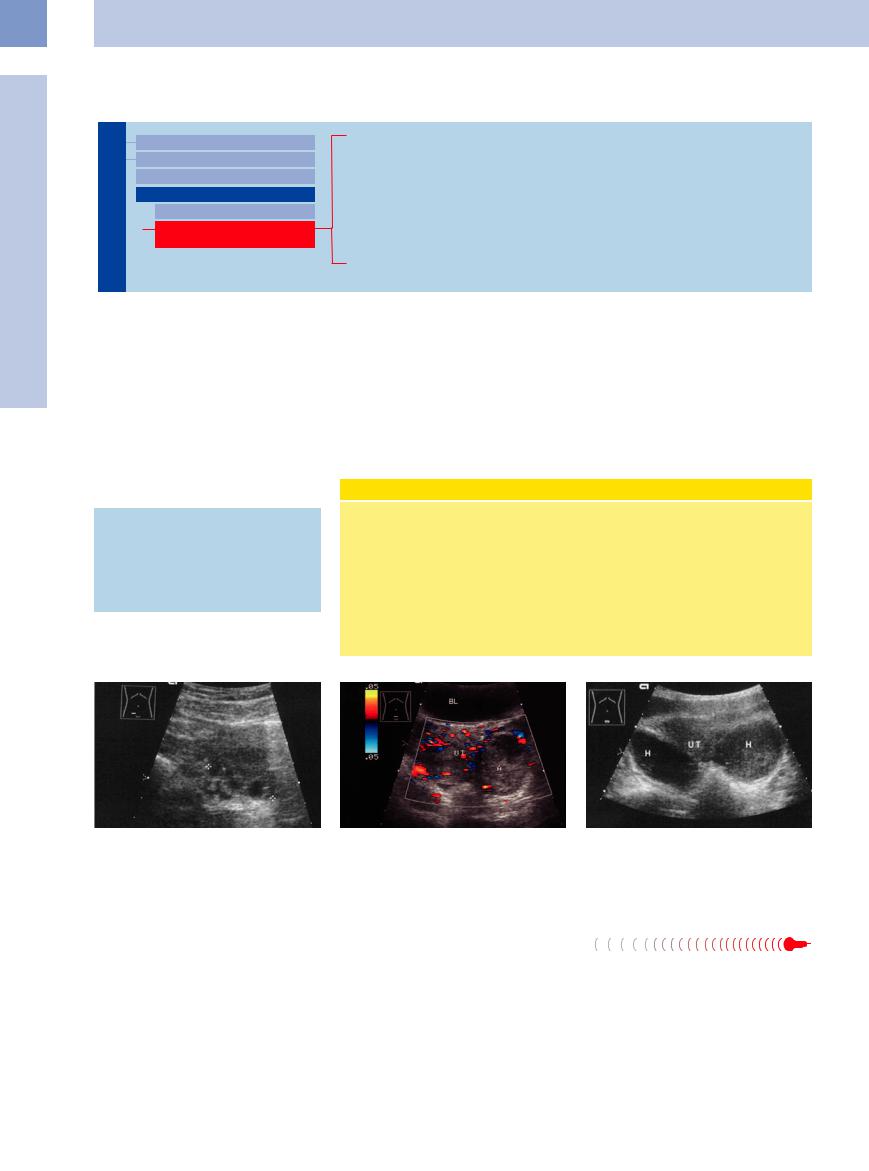

Fig. 13.96 Endometriotic cysts of the ovary. Multiple hy- |

Fig. 13.97 Large, solitary histological endometriotic cyst |

poechoic foci in the ovary. |

(surgery and histology; first sonographic diagnosis: ab- |

|

scess). The clinical and sonographic diagnosis was ab- |

|

scess. The absence of vascularity is not consistent with |

|

ovarian carcinoma. BL = bladder; UT = uterus. |

Thecomatosis

Thecomatosis is a pure stromal hyperplasia causing moderate enlargement of the ovary, which undergoes nodular changes. Histologically, the cortex is hyperplastic and shows intracellular fat deposits. Stromal hyperplasia occurs only in menopause.

Fig. 13.98 Endometriosis with bleeding: hypoechoic mass, hematomas (H) due to bleeding in foci of endometriosis. UT = uterus.

464

Inflammatory Adnexal Mass

Enlargements of the ovaries due to inflamma- |

● |

Tubo-ovarian abscess or infections originat- |

densely matted (making them difficult to |

tion fall under the heading of adnexal masses. |

|

ing from the fallopian tube (Fig.13.100, |

distinguish from carcinoma) |

They include the following entities: |

|

Fig.13.101; see also Fig.13.79) |

|

● Ovarian abscess (Fig.13.99) |

● |

Hematogenous tuberculosis. Conglomerate |

|

|

|

masses are formed, usually bilateral and |

|

13

Ovaries

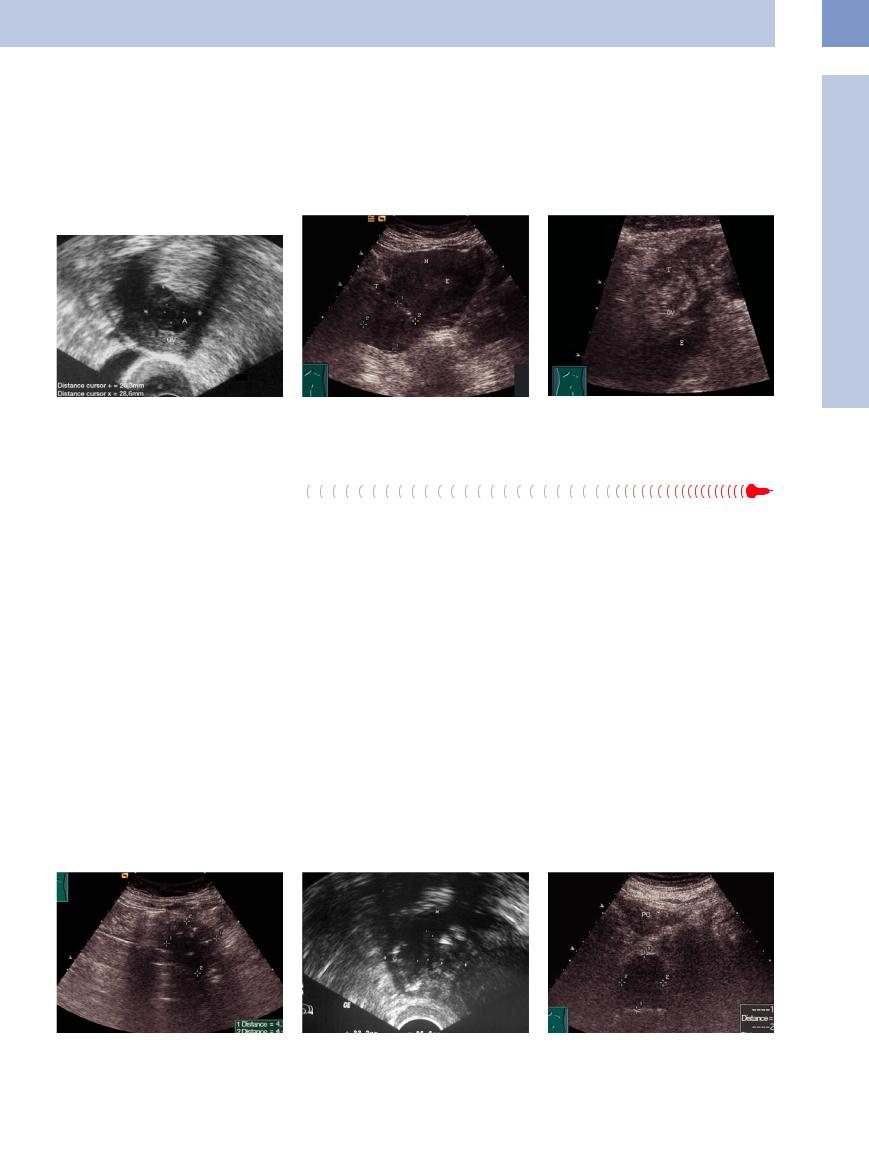

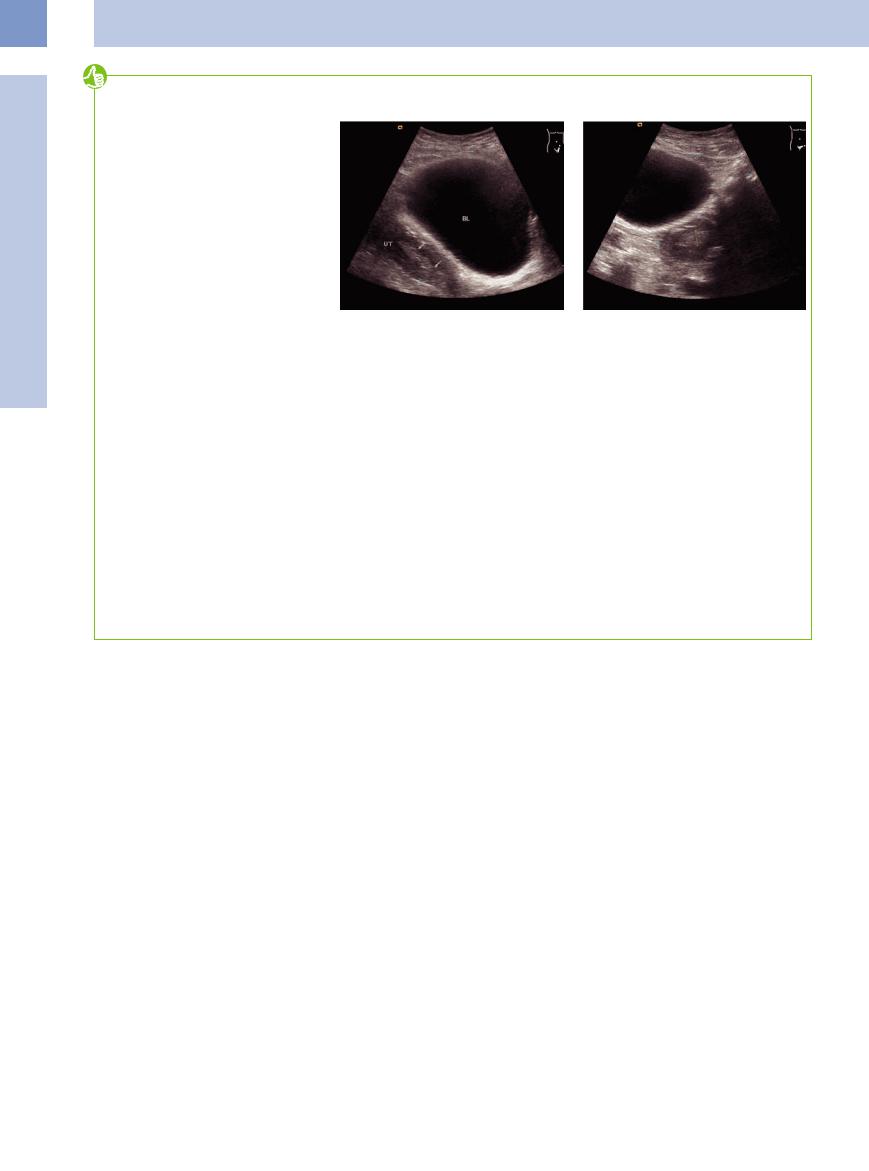

Fig. 13.99 Ovarian abscess: The ovary (OV) is enlarged |

Fig. 13.100 Adnexitis: nonhomogeneous enlarged ovary |

and hyperechoic; it appears in the center anechoic to |

(cursors) causing pain under palpation. |

hypoechoic as a sign for an abscess. |

|

Ovarian Carcinoma

Sonographically ovarian tumors of uncertain importance can only be assessed by morphological criteria such as solid or cystic portions, size of cysts, wall thickness, and septation. A central vascularization is a sign of malignancy in tumors of the adnexa. Biopsies to establish a diagnosis are contraindicated due to the risk of spreading along the injection canal. To date, non-invasive diagnostic measures cannot replace surgical staging and give reliable assessments of the operability of ovarian cancer.

Any kind of tissue can give rise to a malignant tumor, but only tumors derived from the germinal epithelium are classified as ovarian carcinoma. Theca-like transformation in ovarian tumors leads to small amounts of estrogen production in 15–20% of all epithelial cancers.

Tumors in postmenopausal women who are not on hormone replacement therapy are always suspicious. If findings are equivocal, diagnostic laparoscopy is always advised, although a diagnosis can not always be made. Surgical

exploration and extirpation is needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Some 10% of ovarian cancers are determined by genetic factors. Characteristics of familial ovarian cancer are clustering of cases within the family, often associated with increased cases of breast cancer (hereditary breast and ovarian cancer), less often associated with bowl and uterine cancer (HNPCC) or other tumors (Li–Fraumeni syndrome). An uncharacteristically early age of onset is noticeable. Ovarian cancer is mainly diagnosed in late stages of the disease, but screening will not improve early detection. This is why general screening for ovarian cancer was not recommended in the latest guidelines (2007).

Sonographic features. Carcinoma can have almost any sonomorphological appearance: cystic, hyperechoic, hypoechoic, and nonhomogeneous (Figs. 13.102, 13.103, 13.104). Large tumors contain nonhomogeneous solid com-

Fig. 13.101 Adnexitis: nonhomogeneous hypoechoic fallopian tube (T), nonhomogeneous hyperechoic ovary (OV), surrounded by a fluid collection (E).

ponents, may show central anechoic necrosis, and tend to invade neighboring structures, producing ill-defined margins. It is common for ovarian carcinoma to coexist with uterine or tubal cancers. Primary malignant tumors of the ovary are indistinguishable from metastases arising from other primary malignancies.

Endometrioid adenocarcinomas are more heavily permeated by cysts and papillomas. They account for approximately 5% of ovarian tumors (Fig.13.105).

Ovarian cancers secreting hormones can cause hyperplasia of the endometrium (Fig.13.106, Fig.13.107).

Peritoneal carcinomatosis. Serous or mucinous carcinomas usually become disseminated throughout the abdominal cavity while the primary tumor itself is still relatively small. The peritoneum in these cases is studded with small tumor nodules and shows irregular hyperechoic thickening. Metastases are seeded

Fig. 13.102 Ovarian carcinoma: nonhomogeneous hypoechoic/hyperechoic mass (cursors) in the lower abdomen.

Fig. 13.103 Ovarian carcinoma, transvaginal ultrasonography; same patient as in Fig. 13.101.

Fig. 13.104 Ovarian carcinoma: hypoechoic tumor (cursors) combined with metastasis and intensive hypoechoic peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC).

465

13

Female Genital Tract

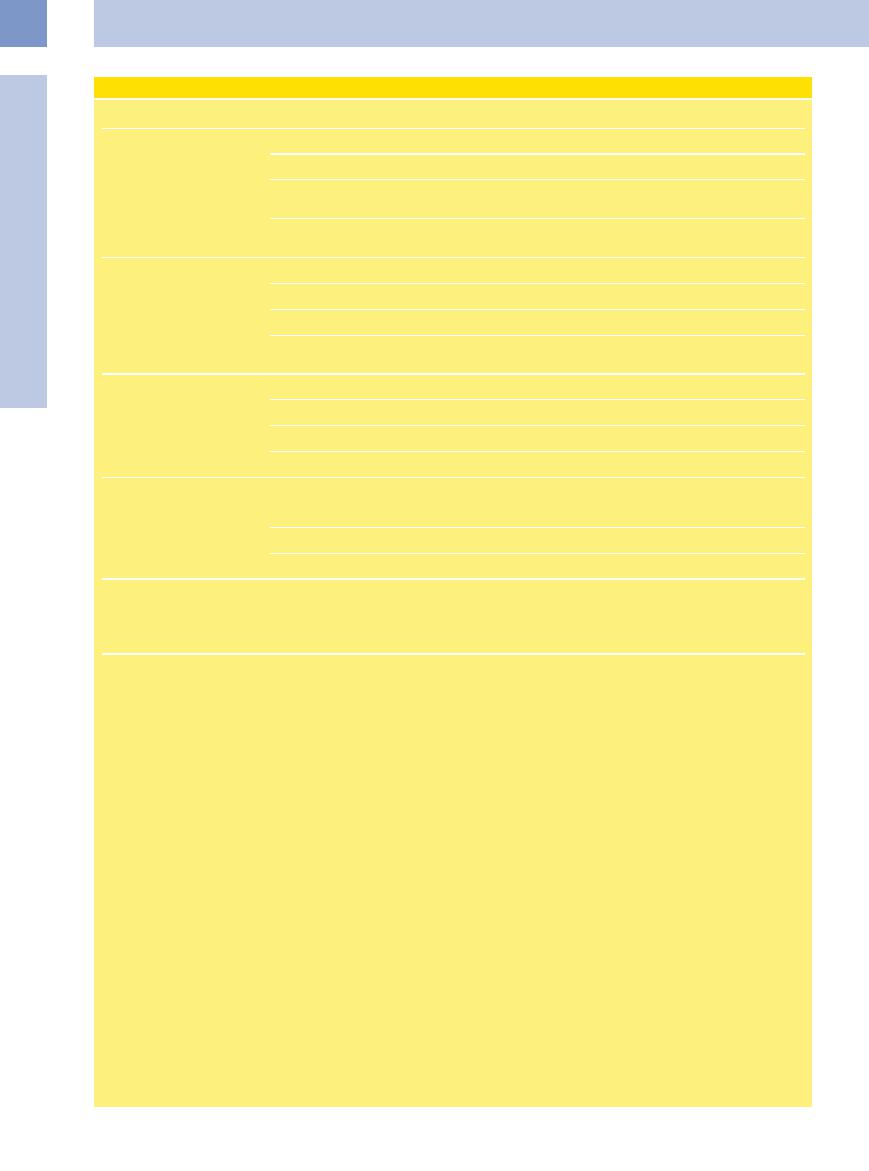

T and FIGO Categories for Ovarian Cancer (after WHO 201312)

TNM |

FIGO |

|

Description |

T1 |

I |

|

The cancer is confined to one or both ovaries |

T1a |

|

IA |

The cancer is only inside one ovary; it does not penetrate the capsule |

T1b |

|

IB |

The cancer is inside both ovaries but does not penetrate to the outside and is not in fluid taken from the |

|

|

|

pelvis |

T1c |

|

IC |

The cancer is in one or both ovaries and is either on the outside of an ovary or grown through the |

|

|

|

capsule of an ovary or is in fluid taken from the pelvis |

T2 |

II |

|

The cancer is in one or both ovaries and is extending into pelvic tissues |

T2a |

|

IIA |

The cancer has metastasized (spread) to the uterus and/or the fallopian tubes |

T2b |

|

IIB |

The cancer has spread to pelvic tissues besides the uterus and fallopian tubes |

T2c |

|

IIC |

The cancer has spread to the uterus and/or fallopian tubes and/or other pelvic tissues (like T2a or T2b) |

|

|

|

and is also in fluid taken from the pelvis |

T3 |

III |

|

The cancer is in one or both ovaries and has spread to the peritoneum outside the pelvis |

T3a |

|

IIIA |

The cancer metastases are so small that they cannot be seen except under a microscope |

T3b |

|

IIIB |

The cancer metastases can be seen but no tumor is bigger than 2 cm (0.8 inches) |

T3c |

|

IIIC |

The cancer metastases are larger than 2 cm (0.8 inches) |

N categories |

|

|

|

NX |

IV |

|

No description of lymph node involvement is possible because information is incomplete |

N0 |

|

|

No lymph node involvement |

N1 |

|

|

Cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes close to tumor |

M categories |

|

|

|

M0 |

|

|

No distant spread |

M1 |

|

|

Cancer has spread to the inside of the liver, to the lungs, or to other organs |

T categories for fallopian tube cancer

Tx

Tis

T1

T1a

T1b

T1c

T2

T2a

T2b

T2c

T3

T3a

T3b

466

13

Ovaries

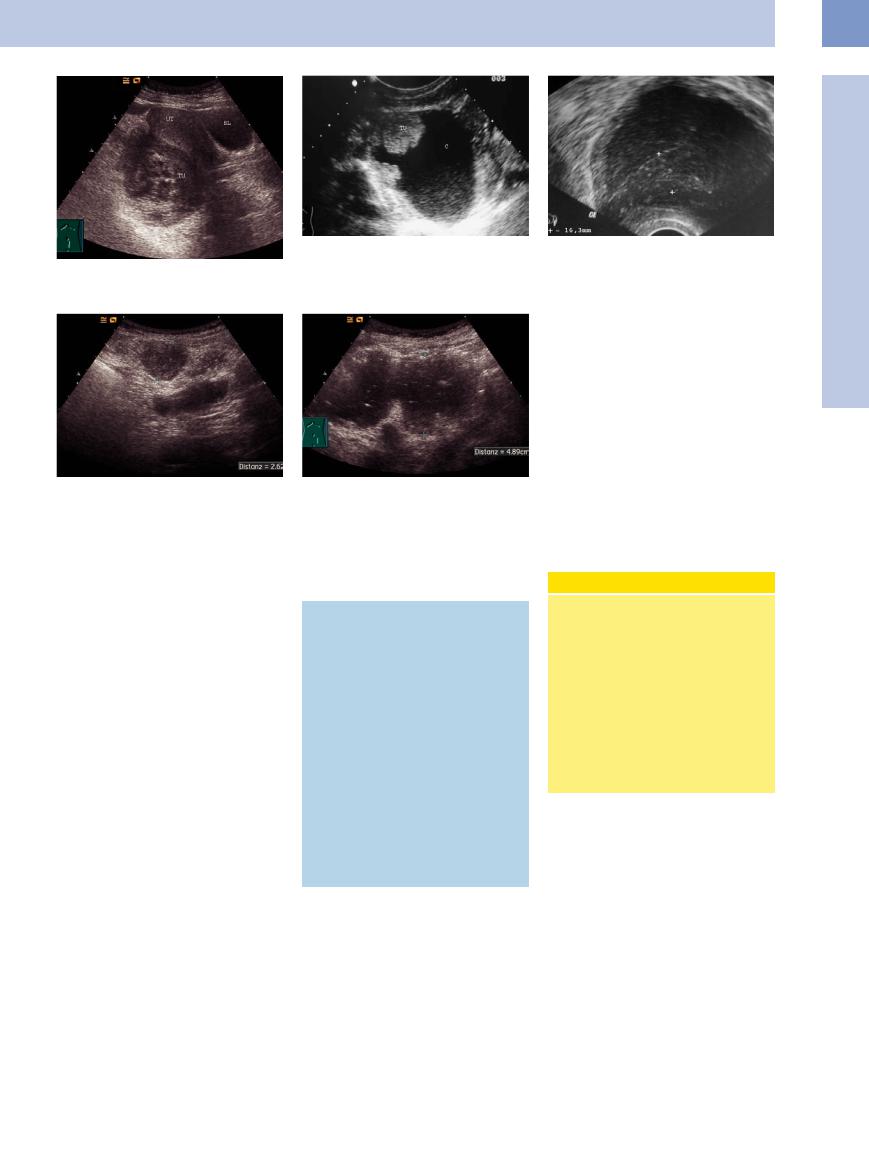

Fig. 13.105 Endometrioid ovarian carcinoma (TU), complex hyperechoic/cystic mass. UT = uterus; BL = bladder.

Fig. 13.108 Peritoneal carcinomatosis (cursors) in a nonovarian carcinoma of the ovary; 59-year-old woman: peritoneal carcinomatosis without a detectable ovarian carcinoma.

Fig. 13.106 Cystadenocarcinoma: hyperechoic polypoid masses (TU) of the cystic epithelium; C = cyst.

Fig. 13.109 Malignant ascites caused by a peritoneal carcinomatosis; nonhomogeneous fluid suspension with deposits of echogenic spots.

Fig. 13.107 Endometrial hyperplasia (transvaginal scan) in ovarian carcinoma: uterus with endometrial hyperplasia (16.3 mm).

early to the greater omentum (Fig.13.108). A large, flat, confluent, hypoechoic tumor may be formed ( 8.3a,d,

8.3a,d,  8.6f, Fig. 8.34). Hypoechoic masses also form on the diaphragm and along the umbilical vein. With the associated obstruction of lymphatic drainage, the serous fluid produced by the tumor cells usually leads to a copious ascites that is often bloodtinged on percutaneous aspiration (Fig.13.109). Cytological analysis of the ascites has a diagnostic accuracy of 80%.

8.6f, Fig. 8.34). Hypoechoic masses also form on the diaphragm and along the umbilical vein. With the associated obstruction of lymphatic drainage, the serous fluid produced by the tumor cells usually leads to a copious ascites that is often bloodtinged on percutaneous aspiration (Fig.13.109). Cytological analysis of the ascites has a diagnostic accuracy of 80%.

Metastasis. Lymph node metastases (paraaortic, inguinal, lesser pelvis) are of minor importance. Ovarian carcinoma spreads hematogenously to the pleura, lung, and liver and less commonly to the brain and bone.

Differential diagnosis. Differentiation from intestinal carcinoma can be difficult. Bowel cancers are frequently associated with hepatic and lymph node metastases, but they rarely show omental involvement or peritoneal carcinomatosis with ascites.

In differentiating ovarian cancer from uterine myomas, a short, firm pedicle not attached to the cornual region suggests a subserous myoma, whereas a soft, mobile pedicle connected to the cornual region suggests an ovarian tumor (Fig.13.110, Fig.13.111). The full differential diagnosis is listed in Table 13.3.

Table 13.3 Differential diagnosis of ovarian masses

●Gallbladder hydrops

●Splenic tumor

●Pelvic kidney, renal tumor, hydronephrosis

●Pancreatic cysts

●Mesenteric cysts

●Bowel tumors, diverticulosis

●Tuberculous conglomerate masses

●Nodal packages in the mesentery

●Distended bladder

●Uterine myomas

●Tumors of the pelvic connective tissue (lipoma, sarcoma, endothelioma, retroperitoneal liposarcoma, retroperitoneal pseudomyxoma, osteoma, enchondroma)

●Tumors of the bony pelvis (may invade the connective tissue)

The sonographic criteria for carcinoma are as follows:

●Larger than 5 cm

●Nonhomogeneous, cystic-solid

●Ill-defined margins

●Lobulated or nodulated

●Echogenic

Borderline Criteria

Borderline tumors are tumors that have a low malignant potential:2

●Epithelial tumors

●Confined to the organ

●No stromal invasion

●Amenable to curative surgery

●Five-year survival rate 80–90%, even with peritoneal seeding

●Occurrence in premenopausal women: two-thirds of malignant tumors in women under age 40 are borderline tumors, as opposed to only 10% in women over age 40.

●Broad septa

●Bilateral

●Papillary deposits

●Free fluid

●On palpation: fixed, matted, firm (Table 13.4)

467

13

Female Genital Tract

Fig. 13.110 Tumor in the lower abdomen (abdominal pain): nonhomogeneous cystic mass with suspicion for ovarian tumor.

f Fig. 13.111 Peritoneal duplication; surgical specimen.

Table 13.4 TNM and FIGO classifications for ovarian cancer11

Primary tumor (T)

TNM |

FIGO |

|

T1 |

I |

Tumor limited to the ovaries (one or both) |

T1a |

IA |

Tumor limited to one ovary; capsule intact, no tumor on ovarian surface; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

T1b |

IB |

Tumor limited to both ovaries; capsules intact, no tumor on ovarian surface; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal |

|

|

washings |

T1c |

IC |

Tumor limited to one or both ovaries with any of the following: capsule ruptured, tumor on ovarian surface, malignant cells in |

|

|

ascites or peritoneal washings |

T2 |

II |

Tumor involves one or both ovaries with pelvic extension |

T2a |

IIA |

Extension and/or implants on the uterus and/or tube(s); no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

T2b |

IIB |

Extension to other pelvic tissues |

T2c |

IIC |

Pelvic extension (T2a or T2b) with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

T3 |

III |

Tumor involves one or both ovaries with microscopically confirmed peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis and/or regional |

|

|

lymph node metastasis |

T3a |

IIIA |

Microscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis (no macroscopic tumor) |

T3b |

IIIB |

Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis, ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension |

T3c |

IIIC |

Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis, > 2 cm in greatest dimension, and/or regional lymph node metastasis |

Regional lymph nodes (N) |

||

TNM |

FIGO |

|

NX |

|

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 |

|

No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 |

IIIC |

Regional lymph node metastasis |

Distant metastasis (M) |

||

TNM |

FIGO |

|

M0 |

|

No distant mestastasis |

M1 |

IV |

Distant metastasis (excludes peritoneal metastasis) |

468

Metastases

Ovarian metastases are very rare and originate |

Krukenberg tumor is the term applied to |

metastasize chiefly by the lymphogenous route |

from cancers of the bronchial system, gastro- |

enlarged ovaries (generally both) that are dif- |

and less commonly via the bloodstream. |

intestinal tract, breast, and gallbladder. Ap- |

fusely permeated by epithelial signet-ring cells, |

|

proximately 3% of malignant ovarian tumors |

usually from gastric carcinoma and occasion- |

|

are metastases. |

ally from colon carcinoma. The tumor cells |

|

Pseudomyxoma Peritonei

Peritonei

In pseudomyxoma peritonei, the peritoneal |

carcinoma of the appendix. Pseudomyxoma |

As there is no effective treatment, the dis- |

cavity is filled with a large quantity of mucin. |

peritonei can also arise secondarily from the |

ease runs a malignant course marked by intes- |

Ultrasound demonstrates anechoic fluid in the |

rupture of a mucinous cystoma (usually at op- |

tinal adhesions and obstructions, with patients |

peritoneal cavity (see Fig. 8.33). |

eration) or possibly as a primary epithelial dis- |

dying from cachexia. |

The cause may be tumor cells seeded from a |

ease based on peritoneal metaplasia. |

|

mucinous ovarian tumor or a mucinous adeno- |

|

|

Ovarian Tumors (by Histological Criteria)

Histological Criteria)

Because many different cell types exist in the ovaries, a large number of different neoplasms can arise. As a result, the ovaries are subject to a greater diversity of tumor types than any other organ in the human body.

Incidence data.

●Epithelial tumors:

–66% of all ovarian tumors are epithelial tumors

–Of the malignant tumors, 85% are epithelial tumors

●Serous tumors:

–50% of all ovarian tumors are serous tumors

–70% of serous tumors are benign, and 20–25% of serous tumors are true invasive carcinomas

–40% of ovarian carcinomas are serous carcinomas, making this the most common type

●Sex cord–stromal tumors:

–7% of all true ovarian tumors are sex cord–stromal tumors

●Germ cell tumors:

–15–20% of all ovarian tumors are germ cell tumors

–95% of germ cell tumors are benign cystic teratomas

–2–3% of germ cell tumors are malignant

–Approximately 65% of malignant ovarian tumors up to age 20 are germ cell tumors

●Bilateral occurrence:

–20–30% of benign tumors

–30–40% of borderline tumors

–65–75% of carcinomas

Epithelial tumors. Epithelial tumors arise from inclusion cysts in the germinal epithelium. The ovary contains numerous germinal epithelial cysts whose origin is still unexplained. Mixed epithelial tumors occur. Epithelial tumors can vary considerably in size. They may be cystic, cystic/solid, or solid. Most solid tumors are malignant.

Sex cord–stromal tumors. These tumors arise from sexually differentiated mesenchyma.

Classification of Ovarian Tumors5,10

●Superficial epithelial–stromal tumors

–Serous tumors

–Mucinous tumors

–Endometrioid tumors

–Clear cell tumors

–Transitional cell tumors (Brenner tumor)

–Squamous cell tumors

–Epithelial mixed tumors

–Undifferentiated carcinoma

●Sex cord–stromal tumors

–Granulosa–stromal cell tumors

–Sertoli–stromal cell tumors, androblastoma

–Sex cord tumors with annular tubules

–Gynandroblastoma

–Unclassifiable

–Steroid (lipid) cell tumors

●Germ cell tumors

–Dysgerminoma

–Yolk sac tumor

–Embryonic carcinoma

–Choriocarcinoma

–Teratoma

–Mixed types

●Gonadoblastoma

●Germ cell–sex cord–stromal tumors

They are palpable, hormone-producing ovarian tumors that are composed of one or more cell types. They produce estrogen or androgens.

Germ cell tumors. Germ cell tumors are more prevalent in Africa and Asia than in Europe (5–15% of malignant ovarian tumors), whereas epithelial tumors are less common. Germ cell tumors occur predominantly in childhood and from 20 to 30 years of age; they are rare after menopause. Approximately two-thirds of malignant ovarian tumors in patients under age 20 are germ cell tumors. They are derived from primordial germ cells (direct: dysgerminoma; indirect embryonic: teratoma; extraembryonic tumors: choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumor). Germ cell tumors grow rapidly, are unilateral,

●Tumors of the rete ovarii

●Mesothelial tumors

●Tumors of uncertain histogenesis

●Gestational trophoblastic diseases

●Soft-tissue tumors, not ovary-specific

●Malignant lymphoma

●Unclassifiable tumors

●Metastases

●Tumorlike lesions

–Solitary follicular cyst

–Multiple follicular cysts

–Luteinized cyst in pregnancy

–Hyperreaction luteinalis (multiple lutein cysts)

–Corpus luteum cyst

–Gestational luteoma

–Ectopic pregnancy

–Stromal hyperplasia

–Stromal hyperthecosis

–Massive edema

–Fibromatosis

–Endometriosis

–Nonclassifiable cyst

–Inflammatory lesions

and metastasize by hematogenous and lymphogenous spread. They are very sensitive to chemotherapy and have a favorable prognosis overall. Consistent therapy and follow-ups can provide a cure rate of up to 90%.

Morphological and sonomorphological criteria. Tables 13.5, 13.6, and 13.7 summarize the principal morphological and sonomorphological criteria for the three main groups of superficial stromal tumors, sex cord–stromal tumors, and germ cell tumors. The following box, p. 473, then reviews the essential aspects of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of ovarian tumors.

13

Ovaries

469

13

Female Genital Tract

Table 13.5 Features of epithelial tumors |

|

|

|

Tumor |

Tumor behavior, frequency, Histology, morphology |

Sonographic criteria |

Special features |

|

bilateral occurrence |

|

|

Serous tumors

● Cystadenoma |

● Most common benign |

● Thin cyst wall, lined with |

|

ovarian tumor |

epithelium |

|

● Generally unilateral |

● Serous contents |

|

|

● Usually large cysts |

● Cystadeno- |

● Most common malignant |

● Predominantly cystic with |

carcinoma |

ovarian tumor (1/3 of all |

solid elements |

|

ovarian cancers) |

● Circumscribed thickening |

|

|

of cyst wall |

|

|

● Polypoid structures, intra- |

|

|

tumoral hemorrhage, and |

|

|

necrosis may occur |

|

|

● Stromal infiltration |

Mucinous tumors |

|

|

● Mucinous |

● 25% of all ovarian tumors |

● Multifocal |

cystoma |

● Initially benign, eventually |

● Often septated |

|

degenerates |

● Thin-walled |

|

● 5–20% bilateral (depend- |

|

|

ing on malignancy) |

|

● Mucinous |

● 10% of ovarian carcinomas |

● Mixed cystic and solid |

cystadeno- |

● 20% bilateral |

● Intratumoral hemorrhage |

carcinoma |

|

and necrosis may occur |

Endometrioid |

● 20% of ovarian carcinomas |

● Mixed cystic and solid |

tumor |

● 30–40% bilateral |

● Cyst contents serous or |

|

|

bloody |

|

|

● Foci of bleeding and ne- |

|

|

crosis |

● |

Anechoic mass |

● See “Cystic ovarian |

● |

Smooth surface |

masses” |

●Thin echogenic wall

●Thin septa, possibly multilocular

● Mixed anechoic (cystic ele- |

● See “Cystic ovarian |

ments) to hyperechoic |

masses” |

(cyst wall) |

|

● Nonhomogeneous echo- |

|

genic areas (bleeding and |

|

necrosis) |

|

● Often with ascites in |

|

metastases/peritoneal |

|

metastases |

|

● Variable echogenicity |

● See “Cystic ovarian |

● Fine to coarse internal |

masses” |

echoes in the septated |

|

spaces |

|

● Anechoic (cystic) to echo- |

● Often associated with |

genic (solid) with hypo- |

pseudo-myxoma peritonei |

echoic areas (bleeding and |

|

necrosis) |

|

● Cyst contents hypoechoic |

● Coexists with endometrial |

to echogenic |

carcinoma in 15–30% of |

|

cases |

Clear cell tumor |

● 5–10% of ovarian carcino- |

● Mixed cystic and solid |

● Mixed anechoic and hyper- |

|

|

mas |

|

echoic |

|

|

● 40% bilateral |

|

● Indistinguishable from oth- |

|

|

|

|

er tumors by ultrasound |

|

Transitional cell |

● 1–2% of all ovarian tumors |

● Smooth margins |

● With calcifications: high- |

● Patients are approximately |

tumor (Brenner |

● Usually benign |

● Not visible or up to 2–3 cm |

level internal echoes with |

50 years old |

tumor) |

● Unilateral |

large |

acoustic shadows |

|

|

|

● Calcifications may occur |

|

|

470

Table 13.6 Features of sex cord–stromal tumors |

|

|

|

|

Tumor |

Tumor behavior, frequency, |

Histology, morphology |

Sonographic criteria |

Special features |

|

bilateral occurrence |

|

|

|

Granulosa-stromal cell tumors |

|

|

|

|

● Granulosa cell |

● Most common estrogen- |

● Solid structure |

● Hypoechoic |

● Estrogen production can lead to |

tumor |

producing ovarian tumor |

● Up to 30 cm in diameter |

● Possible cysts |

precocious pseudopuberty in ado- |

|

● Usually unilateral |

|

|

lescents, to uterine and breast |

|

● Frequent malignant |

|

|

enlargement in sexually mature |

|

growth without correla- |

|

|

women, and to endometrial hyper- |

|

tive histology |

|

|

plasia or carcinoma in postmeno- |

|

|

|

|

pausal women |

|

|

|

|

● Can recur after 10–20 years |

● Thecoma |

● Less common than gran- |

● 5–10 cm in diameter |

● Smooth margins |

● Estrogen production |

(theca cell |

ulosa cell tumor |

● Consists of fat-rich stro- |

● Hypoechoic with echo- |

● Rare in puberty, common around |

tumor) |

● Unilateral |

mal cells, collagen-pro- |

genic strands |

menopause |

|

● Generally benign |

ducing cells, and nests of |

|

● Causes menstrual abnormalities and |

|

|

granulosa cells |

|

breast enlargement; endometrial |

|

|

|

|

hypertrophy and carcinoma may |

|

|

|

|

occur |

|

|

|

|

● Often confused with fibroma |

● Ovarian fibro- |

● Most common ovarian |

● Arises from sexually un- |

● Smooth margins, oval, |

● 40% of fibromas > 6 cm associated |

ma |

stromal tumor |

di erentiated mesenchy- |

uniformly hypoechoic |

with ascites |

|

● 4% of all ovarian tumors |

ma |

● Occasional cystic de- |

● Rare development of fibrosarcoma |

|

● Usually unilateral |

● Firm due to collagen |

generation |

● Meigs syndrome: benign ovarian tu- |

|

● Usually benign |

production |

● Often heavily calcified |

mor (fibroma) with ascites and |

|

|

● “Adenofibroma”: also |

|

pleural e usion (usually on the right |

|

|

contains glands and cysts |

|

side), caused by lymphatic obstruc- |

|

|

|

|

tion? |

● Differentiation required from Krukenberg tumor: metastases from bowel or breast tumors

● Sarcoma |

● Highly malignant |

● Solid, less firm than fi- |

● Solid, predominantly |

|

● Pure sarcomas are rare, |

bromas |

hypoechoic (less hypo- |

|

mostly mixed forms: fi- |

● Histological structure re- |

echoic than fibroma) |

|

brosarcoma, leiomyosar- |

sembles “fish flesh” |

|

|

coma, adenosarcoma |

|

|

Sertoli stromal |

● 0.2% of all ovarian |

● Solid, up to 10 cm in |

● Smooth margins, non- |

cell tumors, an- |

tumors |

diameter |

homogeneous hypo- |

droblastomas |

● Usually benign |

● Cells resemble Sertoli |

echoic/hyperechoic |

|

● Unilateral |

and Leydig cells |

texture |

●In young women and children

●In young women (ca. 25 years)

●80% produce androgens, causing hirsutism with beard growth, deep voice, secondary amenorrhea, clitoral hypertrophy, breast and uterine atrophy, alopecia, increased libido

●Androblastomas: incomplete development of a testis from stroma of embryonic gonads; special form composed of ovarian hilar cells (hilar-Leydig cell tumor) may produce estrogen

Steroid (lipid) |

● Usually benign |

● |

Resemble a hyperneph- |

● |

Urinary 17-ketosteroids sometimes |

cell tumors |

|

|

roma, may arise from |

|

elevated |

|

|

|

heterotopic adrenal |

● |

Obesity, virilization, abdominal |

|

|

|

tissues |

|

striae |

|

|

● |

Soft, slightly necrotic |

|

|

13

Ovaries

471

13

Female Genital Tract

Table 13.7 Features of germ cell tumors |

|

|

|

|

Tumor |

Tumor behavior, fre- |

Histology, morphology |

Sonographic criteria |

Special features |

|

quency, bilateral occur- |

|

|

|

|

rence |

|

|

|

Dysgerminoma |

● 5–10% of all ovarian tu- |

● Very fast-growing, solid |

|

● Very radiosensitive |

(gonocytoma, round |

mors, ca. 2% of malig- |

tumor up to about 30 cm |

|

● Good prognosis |

cell sarcoma, semi- |

nant ovarian tumors up |

|

|

● Occult tumors on the opposite |

noma) |

to age 20 |

|

|

side |

|

● Most common malignant |

|

|

|

|

germ cell tumor (50%) |

|

|

|

|

● Most common malignant |

|

|

|

|

tumor in pregnancy and |

|

|

|

|

intersexuality |

|

|

|

|

● 10% bilateral (large tu- |

|

|

|

|

mors) |

|

|

|

Yolk sac tumor |

● 20% of immature germ |

● Reticular epithelial cells |

|

● Produces AFP (used as tumor |

(entodermal sinus |

cell tumors of the ovary |

● Papillary structure |

|

marker) |

tumor) |

● Malignant |

|

|

● Better prognosis today with |

|

|

|

|

cytostatics |

Teratomas |

|

|

|

|

● Dermoid (benign |

● 15% of all ovarian tumors |

● Composed of embryonic |

● Ill-defined margins |

● In younger women |

teratoma, |

● One-third of all benign |

germ cells |

● Solid with high non- |

● Strictly speaking, a retention |

dermoid cyst) |

ovarian tumors |

● Grows very slowly |

homogeneous echo- |

cyst; enlarges when skin secre- |

|

● 80% of all germ cell |

● Rarely larger than fist- |

genicity, occasionally |

tions expand the cyst sac |

|

tumors |

size |

with calcium |

● Prone to torsion, suppuration; |

|

● Benign, but the squa- |

● Surface smooth but ir- |

● Cyst with layered in- |

may penetrate into the rectum |

|

mous portion may show |

regular |

ternal structure; path- |

|

|

malignant change (1%) |

|

ognomonic, especially |

|

|

● Usually unilateral |

|

when echogenic part |

|

|

|

|

is anterior (floating se- |

|

|

|

|

bum, liquid at body |

|

|

|

|

temperature) |

|

|

|

|

● May contain tooth bud |

|

|

|

|

and bone with acous- |

|

|

|

|

tic shadowing |

|

● Malignant solid |

● Highly malignant |

● Dermoid with disordered |

|

● Destructive spread |

teratomas |

|

cell pattern and glial |

|

● Metastases |

|

|

proliferation |

|

|

|

|

● Rapid growth |

|

|

● Struma ovarii |

|

● Monodermal neoplasm, |

● Requires di erentia- |

● Hormone production can cause |

|

|

predominates in thyroid |

tion from hemorrhagic |

hyperthyroidism |

|

|

tissue |

cyst, cystadenoma, fi- |

|

|

|

|

broma |

|

472

Clinical Aspects, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Ovarian Tumors

Symptoms

●There are no early symptoms.

●Ovarian tumors cause few if any complaints and have ample room to expand from the lesser to the greater pelvis. Often they are detected only after the abdominal girth increases. Many of these tumors are detected incidentally.

●Uterine bleeding (7%) occurs when there is a coexisting uterine tumor or when the ovarian cancer has penetrated the vaginal wall.

●Estrogen production and its associated symptoms occur in 18% of all ovarian tumors and 25% of ovarian carcinomas.

●In 70% of cases, metastases are already present at operation.

Typical complications

●Torsion of a pedunculated uterine tumor (10–20%) may be caused by an external force acting on the tumor (sudden deceleration), especially if the mass contains fluid. A gradual occlusion of the blood supply causes a gradual increase in complaints, while sudden occlusion produces a shocklike condition with peritonitis. Torsion can lead to necrosis.

●Infections occur in 2% of ovarian tumors, usually owing to the migration of infectious microorganisms from the bowel. They can lead to suppuration (pyogenic organisms) and putrefaction (putrefactive bacteria). The results are high intermittent fever and life-threatening peritonitis.

●Incarceration occurs if the tumor cannot move upward out of the lesser pelvis.

●Rupture occurs in 3% of all ovarian cysts, usually spontaneously and often as a result of torsion. Life-threatening internal bleeding can develop. The draining cystic fluid and spillage of cells lead to chronic ascites.

●Complaints relating to the complications are low back pain, a bloated feeling, difficulties in passing urine and stool, varices, and leg edema.

Diagnosis

Gynecological examination and ultrasonography by an experienced examiner using modern equipment should ensure that no malignant tumors are discovered incidentally at operation.

Tumor locations:

●Large ovarian tumors can exert traction on the uterus, causing it to assume a transverse position in the lesser pelvis.

●Small ovarian tumors are located in the lesser pelvis adjacent to the uterus, which they may displace.

●Dermoid cysts are often located anterior to the uterus.

●Tumors of the pelvic connective tissue are difficult to define.

Rule:

●The attachment of a tumor is located opposite the site of greatest mobility. Testing this mobility sign will usually help in distinguishing between an abdominal tumor and a tumor of genital origin.

Suspicious signs during palpation:

●Palpable nodule on the uterine attachment of the sacrouterine ligaments, in the cul-de-sac, or on the epiploic appendages of the rectum.

●Ovaries palpable after menopause.

Imaging and invasive studies

The patient may be examined by ultrasound, laparoscopy, CT (in exceptional cases; see below), or laparotomy with extirpation and histological evaluation.

Ultrasound with a well-distended bladder:

●Criteria for malignancy: solid, irregular, mixed solid/cystic elements, ascites.

●Criteria for benignancy: smooth, unilocular or multilocular cysts.

Cysts should not be aspirated:

●Danger of rupture and possible cell spillage.

●Needle aspiration cannot exclude intracystic carcinoma.

●Cyst aspiration is never curative.

Aspiration of ascites:

● The ascites in early ovarian carcinoma is free of tumor cells.

Laparoscopy:

●Laparoscopy is unsafe owing to the risk of cell spillage and uncertain because a wedge excision may be nondiagnostic. Because every ovarian tumor ultimately should be removed, laparoscopy merely wastes time.

CT:

●Whenever possible, CT should be performed only after menopause because of radiation exposure to the ovaries.

Treatment

●Wait for menstruation to occur before performing surgery, as functional cysts will regress spontaneously.

●With malignant ovarian tumors, both ovaries and fallopian tubes should almost always be removed along with the uterus and greater omentum because of the likelihood of metastases.

●A cure is possible if the largest tumor remnant left behind is no larger than 1–2 cm.

●Ovarian tumors are responsive to chemotherapy. If tumors recur, they do so quickly after the therapy is discontinued.

●Even during pregnancy, every true ovarian tumor should be surgically removed because of the risk of torsion, rupture, and suppuration in the puerperium (10%).

Prognosis

The prognosis depends critically on the timing of the first operation and the corresponding tumor stage, the histological type (serous tumors have a poorer prognosis than mucinous or endometrioid lesions), the degree of tumor differentiation (grading), the postoperative residual tumor mass, the age and the overall health of the patient.

The 5-year survival rates (after surgery and chemotherapy) are as follows:

● Stage I–IIA |

65–90% |

● Stage II |

approx. 50% |

● Stage III |

approx. 10–12% |

● Stage IV |

approx. 1–2% |

Today, 70% of ovarian carcinomas are diagnosed in stage III or IV; the 5-year survival rate is 30%.

13

Ovaries

473

13

Female Genital Tract

Tips, tricks, and pitfalls

In general

●Uterus, cervix, vagina, and ovary need to be examined routinely and systematically, even by the examiner not belonging to the group of “specialists.” History and clinical findings ought to be integrated.

●Complexity in anatomy in the region examined must be considered.

●Color-coded sonography and contrast-en- hanced ultrasonography (CEUS) must be used carefully.

●Further imaging techniques must be available, such as transvaginal endosonography (TVS) and MRI. In uterine adenomyomatosis especially, MRI shows better specificity; otherwise TVS and MRI are equally useful in classifying myometrium and layers of endometrium.

●The occurrence of sarcoma in patients with myoma is only about 0.27%. There are no good ultrasound criteria for it.

Special

●Before menopause:

–Routinely, ovaries are detected in lower abdominal sections by following parametria from ovary in the direction of iliacal vessels (color-coded sonography), taking the obturator muscle as another landmark.

–Ovaries are detected by their (small, cystic) follicles, showing different degrees of maturity, and their oval shape; in midcycle liquid masses in the minor pelvis are normal as a result of ruptured graafian follicles.

Fig. 13.112 a and b Unevenly thickened endometrium (arrows and distance bars) exceeding 12.4 mm—highly suspicious of carcinoma of endometrium (no hormonal therapy); lower abdominal sections.

●After menopause:

–Endometrium thickness less than 4–5 mm presents no risk.

–If the endometrial thickness is greater than this, histology is needed, especially if it is 20 mm or more.

–In asymptomatic patients, an endometrial diameter of more than 1 mm is regarded as a cancer risk situation (Fig. 13.112).

In cystic lesions, the same tumor entity may show different sonographic features, and vice versa: the same sonographic tumor appearance may represent different histologic entities.

●Signs of malignity:

–Uneven texture

–Ascites

–More than four papillary structures

–Multilocular cysts

–Strong vascularization

●Signs of benignity:

– Cystoid structure solitary and less than 7 mm in diameter

–Acoustic shadowing

–Smooth contour

–No vascularization

Experienced examiners can distinguish the harmless from the harmful in TVS.

References

[1]Kaiser R, Pfleiderer A. Keimzelltumoren. In: Lehrbuch der Gynäkologie. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1985

[2]Frank K, Goldhofer W. Uterus und Adnexe. In: Rettenmaier G, Seitz K (eds.). Sonographische Differentialdiagnostik. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1999

[3]Kozlowski P, Böhmer S. Gynäkologische Fragestellung in der Ultraschalldiagnostik. Landshut: ecomed, 1991

[4]Schmidt-Gollwitzer M. Abnorme vaginale Blutungen. In: Martius G, Schmidt-Gollwitzer M (eds.). Differentialdiagnose in Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1984; p.16

[5]Sohn C, Krapfl-Gast AS, Schiesser M. Checkliste Sonographie in Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1998

[6]Kaiser R, Pfleiderer A. Geschwülste. In: Lehrbuch der Gynäkologie. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1985

[7]Schmidt-Gollwitzer K, Schmidt-Gollwitzer M. Der palpable Unterbauchtumor. In: Martius G, Schmidt-Gollwitzer M (eds.). Differ-

entialdiagnose in Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1984

[8]Moltz L. Androgenisierungserscheinungen. In: Differentialdiagnose in Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1984; p. 46

[9]Merz E. Anatomie des weiblichen Beckens. In: Sonographische Diagnostik in Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe. Vol1, 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1997

[10]Scully RE. Histological typing of ovarian tumours, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000

[11]Tavassoli FA, Deville P, Eds. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs (IARC/World Health Organization Classification of Tumours). Lyon: IARC, 2003

[12]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Ovarian Cancer: Including Fallopian Tube Cancer and Primary Peritoneal Cancer V1.2013

474