- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

9

Kidneys

Cyst-like Metastases

Hypoor anechoic structures in highly malignant non-Hodgkin lymphomas may be taken for cysts. The diagnosis is made by the underlying dysfunction and its regression rate under therapy (see Fig. 9.73).

Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

Kidneys

Anomalies, Malformations Diffuse Changes Circumscribed Changes

Anechoic Structure

Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

Complex Structure

Hyperechoic Structure

Echogenic Structure

Dromedary Hump, Fetal Lobulation

Abscess

Hemorrhagic Cyst

Fresh Renal Infarct

Hematoma

Renal Cell Carcinoma

Urothelial Carcinoma

Malignant Lymphoma

Metastasis

Papillary Adenoma, Oncocytoma, Inflammatory Tumor

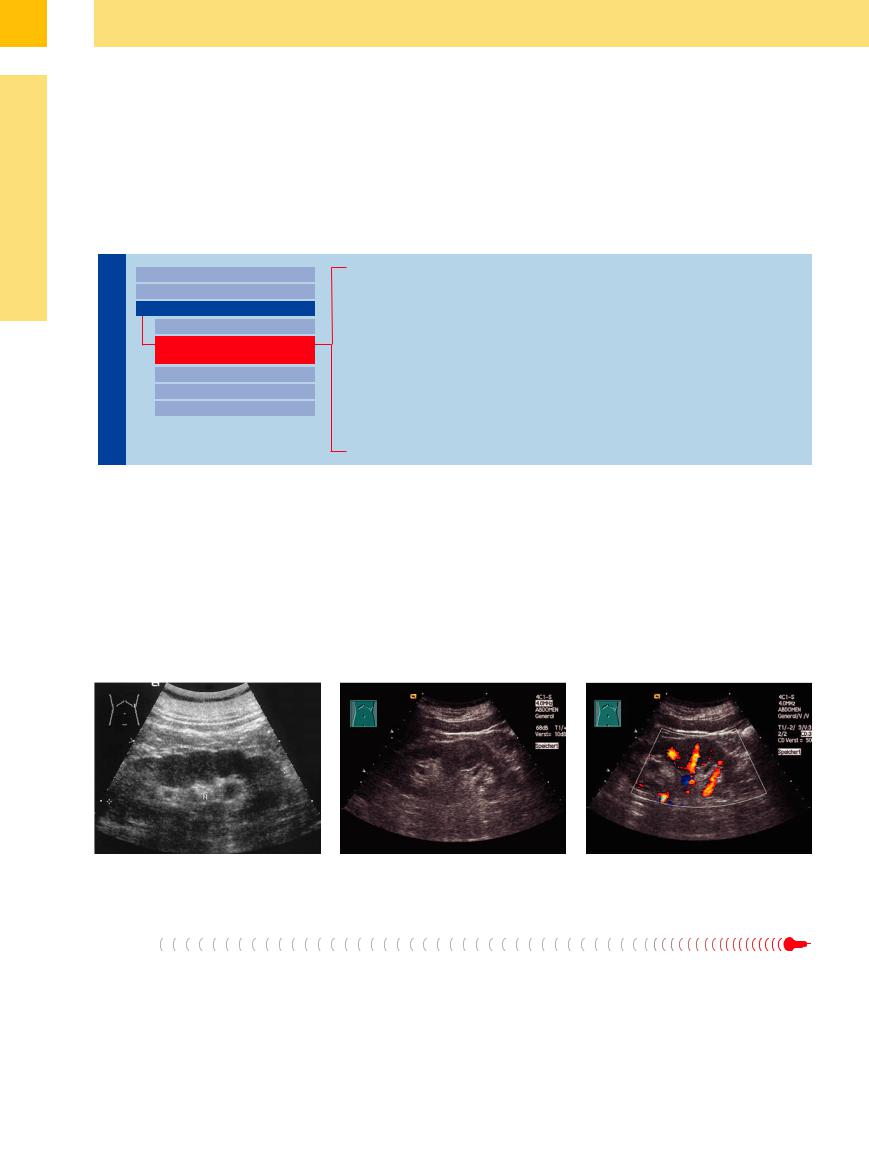

Dromedary Hump, Fetal Lobulation

Dromedary hump. The physiological dromedary hump in the left kidney appears as a hypoechoic “mass” that is occasionally difficult or impossible to distinguish from a tumor. To exclude this diagnosis, it is helpful to inspect the structure closely in a zoomed view to confirm a normal renal architecture, and to obtain a color Doppler view showing an absence of irregular tumor vessels as well as the absence of an abnormal vascular rim. The differentiation be-

tween such “pseudotumors” and solid renal masses can be made by CEUS: pseudotumors have the same enhancing characteristics as the surrounding parenchyma in all phases, whereas the enhancement in renal tumors differs from the surrounding parenchyma, with a difference in degree or distribution of enhancement in at least one vascular phase, in most cases.2

Fetal lobation. Fetal lobation is a developmental anomaly based on incomplete fusion of the fetal nephrons. It is characterized by a normal but undulating parenchyma that bulges outward and also toward the renal sinus. The constricted areas between the bulges represent sites of normal parenchymal thickness and are not rarefied areas like those caused by scarring (Fig. 9.66).

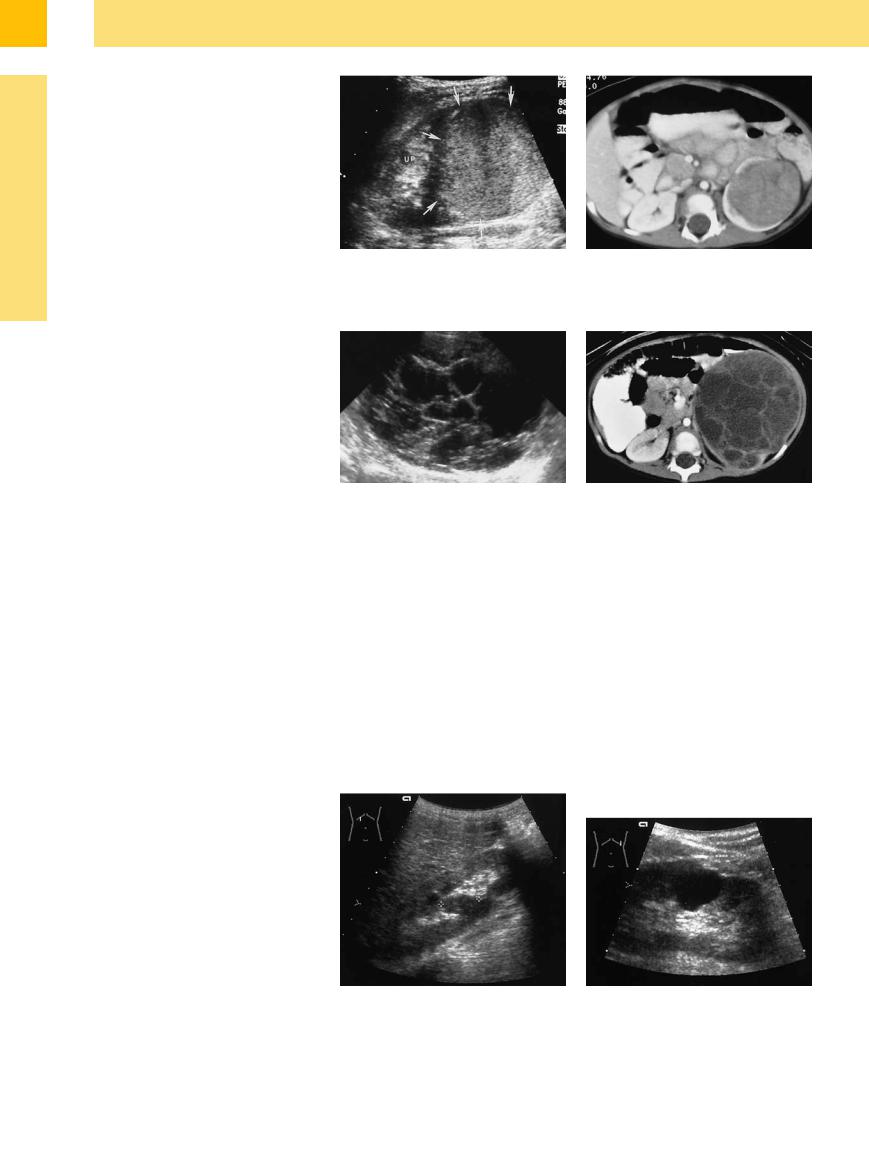

Fig. 9.66 Renal contour distortion. a In fetal lobation.

Abscess

Abscesses in and around the kidney can result from local abscess formation (pyelonephritis, usually E. coli) or from the hematogenous spread of infection (usually staphylococcal). They can spread beyond the renal capsule to form a perinephritic abscess, or they may spread into the perirenal fat, forming a paranephritic abscess.

b Physiological, hypoechoic dromedary hump in the left renal border, indistinguishable from a tumor (see  9.4a). M = spleen; N = kidney.

9.4a). M = spleen; N = kidney.

Their sonographic features are diverse. A simple abscess produces a mass effect creating a bulge in the renal outline. It shows a hypoechoic to heterogeneous echo structure and usually has ill-defined margins. The sonographer should look for gas bubbles, which are a common phenomenon and appear as focal

c Regular vessels in CDS, consequently no tumor.

echogenic inclusions with or without reverberations (Fig. 9.30, Fig. 9.67).

Perirenal abscesses appear as ill-defined masses that may spread in an inferior or lumbar direction. Emphysematous and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis are special forms.

350

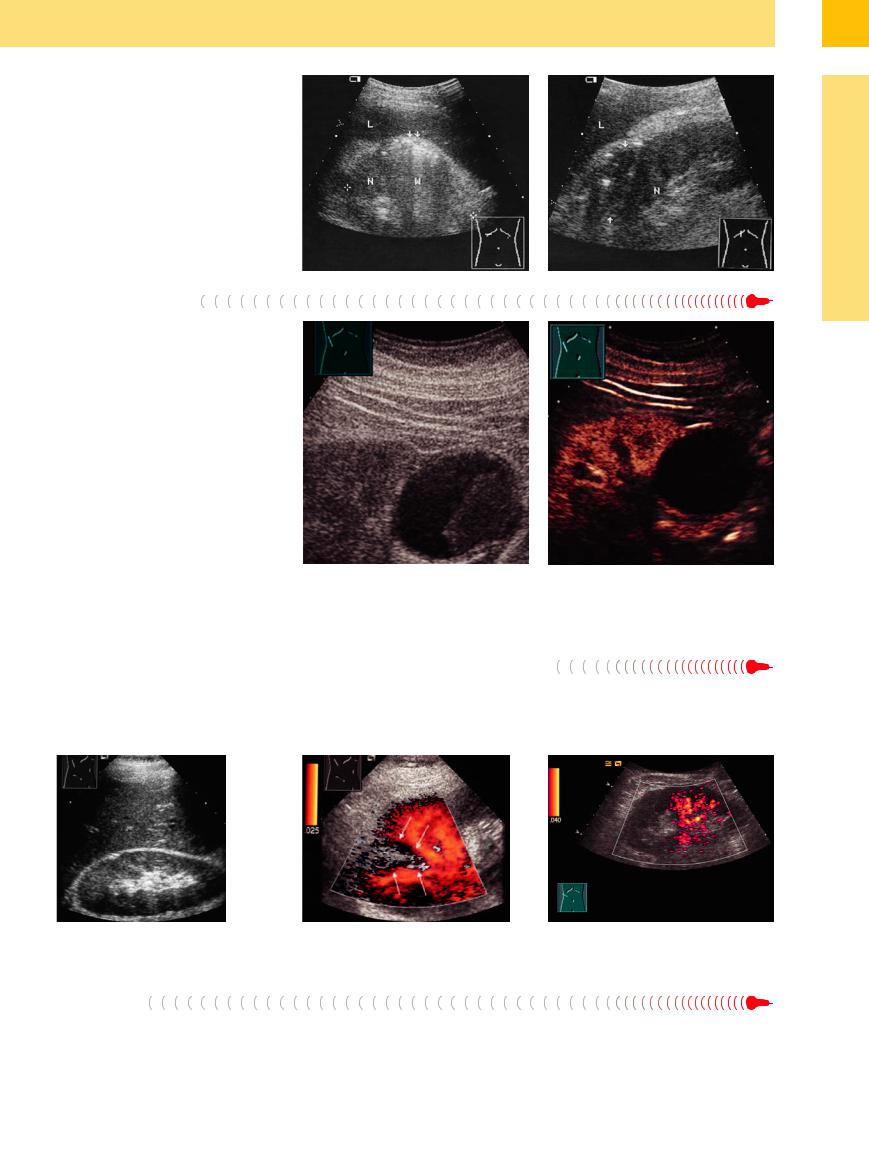

Fig. 9.67 Renal abscess, emphysematous pyelonephritis. L = liver; N = kidney.

a Echogenic bacterial gas bubbles with reverberations (arrows, W) before medical treatment.

b After antibiotic treatment: hypoechoic mass (arrows), contour distortion, ill-defined margins, and scattered echogenic gas bubbles.

While some cyst criteria such as smooth margins and a round shape are maintained in a hemorrhagic cyst, the bleeding causes the initial anechoic mass to become more reflective. This makes the cyst difficult to distinguish from a tumor. The diagnosis can be established by power Doppler or CEUS, with the latter delivering the more accurate results (Fig. 9.68,

Fig. 9.77).

9

Circumscribed Changes

Fig. 9.68 Renal cyst with tumorous mass (images courtesy of Professor C. Goerg, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Marburg, Germany).

a Gray-scale image: hypoechoic mass within a cystic lesion.

b CEUS: no enhancement; probably hemorrhagic lesion, Bosniak II.

Fresh Renal Infarct

A fresh renal infarct is seldom diagnosed clin- |

infarct more often. Especially in gray-scale ul- |

ically and is usually detected incidentally. |

trasound, the infarct displays a typical wedge |

When color Doppler ultrasound (or even bet- |

shape with the base directed toward the renal |

ter, CEUS) is employed, one can find this kind of |

capsule. The late stage is marked by surface |

retractions and focal rarefied areas in the parenchyma due to scarring and fibrous contracture (Fig. 9.69).

Fig. 9.69 Fresh renal infarct.

a Survey scan shows increased echogenicity in the upper pole of the right kidney.

b Color Doppler: the wedge-shaped avascular region (arrows) confirms the infarct. The patient presented clinically with flank pain.

c Extensive renal infarction, power Doppler: avascular area of the upper pole of the right kidney depicting the infarction.

Hematoma

Like renal infarcts and hematomas at other locations, a renal hematoma or contusion undergoes structural changes over time. It appears initially as a hyperechoic or isoechoic

mass that causes a bulge in the renal outline. The echo structure of the mass is somewhat irregular compared with the normal renal parenchyma. Later the hematoma becomes less

echogenic and may culminate in a residual secondary cyst or pseudocyst. Diagnosis, extent, and follow-up are the domain of color Doppler ultrasound and CEUS (Fig. 9.70).

351

9

Kidneys

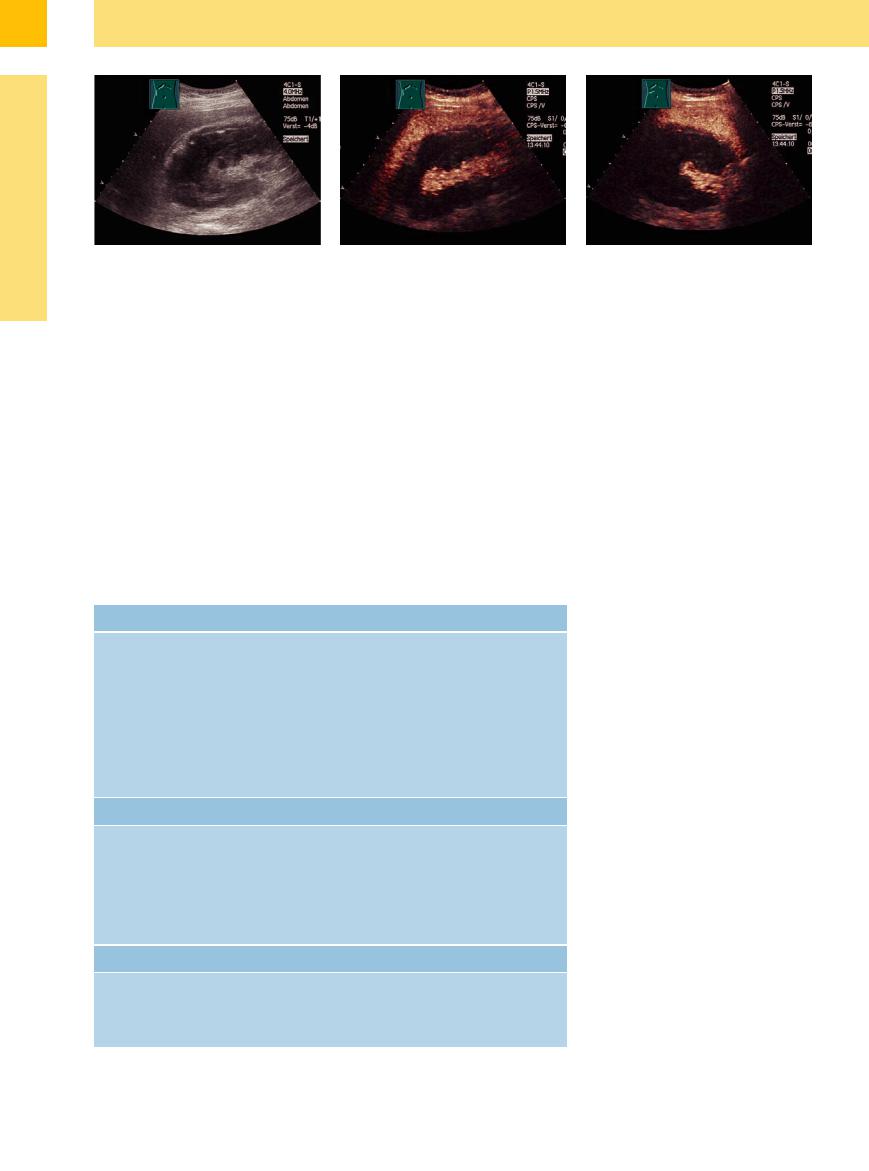

Fig. 9.70 Renal hemorrhage caused by renal puncture.

a Irregular predominantly hypoechoic structure, dissolved architecture.

b CEUS: no contrast perfusion in the upper and middle |

c CEUS, transverse scan. |

parts of the kidney. |

|

Renal Cell Carcinoma

Forms. RCC occurs in three different forms:

●Ordinary solid RCC (most common form)

●Tubulopapillary form

●Cystic RCC (rare)

The 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of genitourinary tumors recognizes over 40 subtypes of renal neoplasms. Since the publication of the latest iterations of the WHO classification in 2004, several novel renal tumor subtypes have been described,13,14 as shown in Table 9.7. Since RCC arises from the renal parenchyma, it displays the immunohistochemical features of uropoietic tubular epithelium.14

Table 9.7 WHO classification of kidney tumors13

The different types of RCC occur with the following frequencies:

●Clear-cell carcinoma about 75%, often underlying pseudocystic transformation

●Papillary RCC 10%, likewise with pseudocystic transformation (also multifocal)

●Chromophobe cell carcinoma 3–5% without a cystic transformation; probably the malignant variant of the oncocytoma

●Spindle cell carcinoma 1–2%; undifferentiated carcinoma of a clear-cell or papillary carcinoma

●Collecting-duct carcinoma < 10%

●Oncocytoma (non-metastasizing) 3–9% of all primary neoplasms

Benign |

Malignant (RCC subtypes) |

Papillary adenoma |

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma |

Oncocytoma |

Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma (MCRCC) |

Metanephric tumors |

Papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC) |

● Adenoma |

Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma |

● Adenofibroma |

Carcinoma of the collecting ducts of Bellini (CDC) |

● Stromal tumors |

Renal medullary carcinoma |

|

Renal carcinoma associated with Xp11 translocations |

|

Renal cell carcinoma associated with neuroblastoma |

|

Mucinous, tubular, and spindle cell carcinoma |

|

Renal cell carcinoma, unclassified |

Neuroendocrine tumors |

Mixed mesenchymal and epithelial tumors |

Carcinoid |

Cystic nephroma |

Neuroendocrine carcinoma |

Mixed epithelial and stromal tumor |

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor |

Synovial sarcoma |

Neuroblastoma |

Nephroblastic tumors |

Phaeochromocytoma |

Nephrogenic rests |

|

Nephroblastoma |

|

Cystic partially di erentiated nephroblastoma |

Other tumors |

|

Mesenchymal tumors |

|

Hematopoietic and lymphoid tumors |

|

Germ cell tumors |

|

Metastatic tumors |

|

Sonographic features. The ultrasound appearance of RCC varies greatly with its stage and histological classification. The most common and characteristic appearance of RCC is that of a round, isoechoic mass in the renal parenchyma that creates a bulge in the renal outline. Hypoechoic tumors are also seen. Atypical hyperechoic tumors are found in 30% of cases; most of these are early stage tumors (see Fig. 9.82, Fig. 9.83). Cystic RCC displays cystic features along with solid elements or septations. Small RCC are homogeneous and ordinarily present a hyperechoic structure. They become a more hypoechoic or irregular structure as they grow (Fig. 9.55a, Fig. 9.78).

Advanced tumors show regressive changes in the form of liquefaction, hyperechoic areas, and calcifications ( 9.4 d). With its wide spectrum of features, RCC can be characterized as chameleon-like in its sonographic appearance (

9.4 d). With its wide spectrum of features, RCC can be characterized as chameleon-like in its sonographic appearance ( 9.4).

9.4).

A narrow, anechoic rim (displaced vessels) is consistently present around the tumor. If this is accompanied by irregular internal tumor vessels within the mass (color Doppler, pattern 4 (after Jinzaki;3 see Fig. 9.71), the ultrasound diagnosis may be considered established. In some cases spectral analysis demonstrates (predominantly in the peripheral vascularity) a high Doppler shift with high-velocity signals (> 70 cm/s), but also tumor vessels with nearly continuous flow signals and a low systolic– diastolic variation.

In CEUS, a rapidly increasing enhancement from peripheral to central is present within 10–20 s due to arteriovenous shunts, leading in larger carcinomas to a rapid wash-out. But solid renal tumors do not show diagnostic perfusion patterns on CEUS, which is thus usually not able to differentiate between malignant and benign solid renal masses (e. g., carcinoma versus angiomyolipoma). CEUS does not improve the sensitivity because there are no reliable criteria to distinguish malignant from benign masses such as angiomyolipoma, oncocytoma, or leiomyoma.6

The differentiation of hyperechoic small carcinoma from angiomyolipoma is more successful in gray-scale ultrasound combined with power Doppler (accuracy 78%15). Power Dop-

352

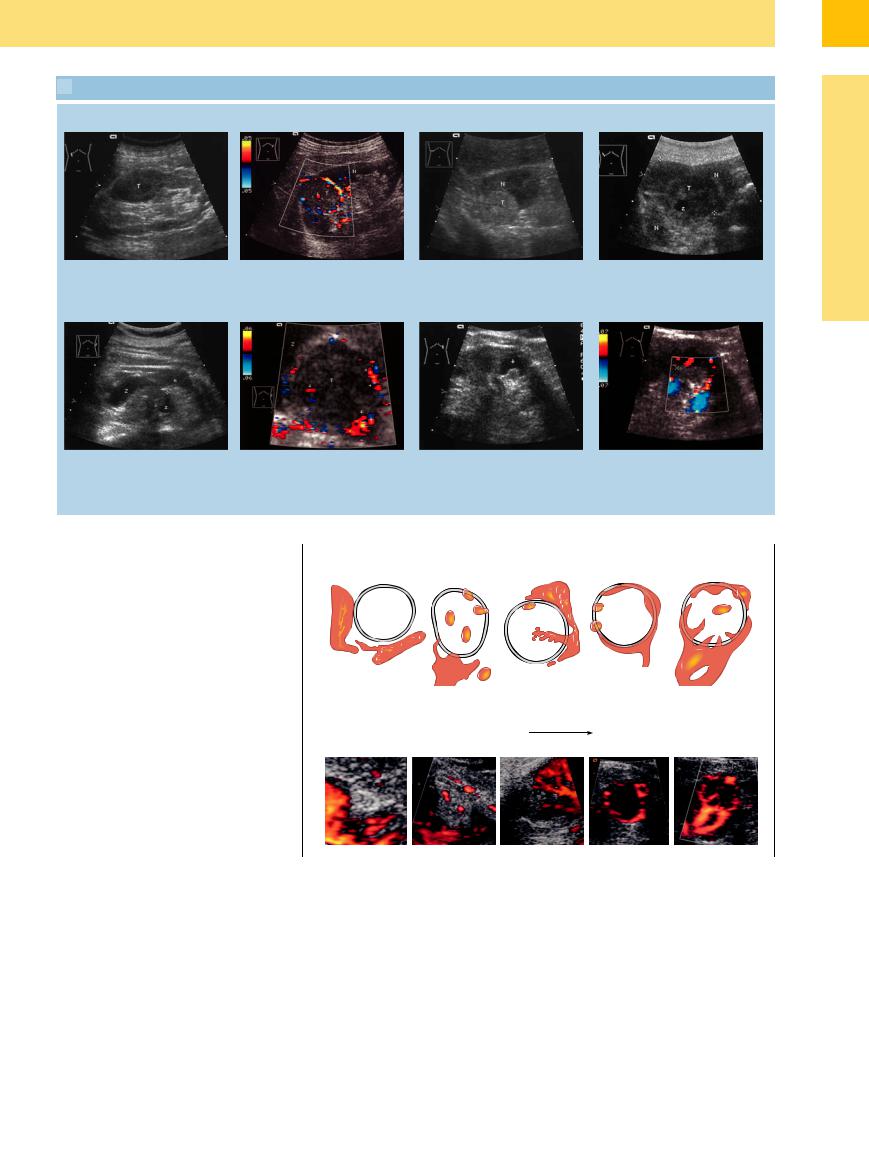

9.4 Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC)

9.4 Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC)

Varying echogenicity

a Hypoechoic tumor (T) with ill-defined |

b Isoechoic mass (T) at the upper pole of |

c Hyperechoic tumor (T). N = renal |

d Partially cystic (Z) transformed tumor. |

margins. Bulging renal outline. |

the kidney, pathognomonic: vascular rim |

parenchyma. |

N = kidney. Isoechoic renal carcinoma |

|

and intratumoral vessels (arrows). |

|

(T), partially cystically transformed (Z, z). |

|

|

|

N = right kidney. |

9

Circumscribed Changes

e Complex structured clear-cell carcinoma. Areas of necrobiotic liquefaction and bleeding (histology). N = kidney; T = tumor.

f Magnification: CDS: Intratumoral and marginal vascularization. Complex structured tumor mass with hyperand anechoic (Z) portions of the right kidney (N). P = renal pelvis.

g and h Differential diagnosis: small focal h CDS. mass (arrow, cursors), 9.6 × 17.8 mm.

g Causing cystically enlarged pyramid (known for 3 years; masses < 1.5 cm can be observed). Probably adenoma.

pler ultrasound can add information to that obtained from gray-scale ultrasound for differential diagnosis of small solid renal lesions.3 The rate of correct diagnosis is significantly increased with combined ultrasound (78%) compared to gray-scale or power Doppler ultrasound alone.

Diagnostic procedure. At present, RCC is detected incidentally in routine ultrasound in 70–80% of cases. It is rarely diagnosed by a targeted search in patients who already have metastatic symptoms. Metastasis may occur by the hematogenous route or by contiguous spread into the renal vein and inferior vena cava.16 Tumor thrombi may occur in the right heart. It is essential, therefore, to closely inspect the renal veins, vena cava, and locoregional lymphatics during ultrasound examination. On the left side, a dromedary hump should be included in the differential diagnosis.

CEUS is recommended in the following clinical situations:11

●Suspected vascular disorders, including renal infarction and cortical necrosis

●Differential diagnosis between solid lesions and cysts presenting with equivocal appearance at conventional ultrasound

●Differentiation between renal tumors and anatomical variations mimicking a renal tumor (“pseudotumors”) when conventional ultrasound is equivocal

●Characterization of complex cystic masses as benign, indeterminate, or malignant to provide information for surgical strategy

●Additional help, when necessary, in the fol- low-up of nonsurgical complex masses

Fig. 9.71 Diagram showing Doppler signal pattern of solid renal lesions (Jinzaki et al3).

●Identification of clinically suspected renal abscesses in patients with complicated urinary tract infection

●In patients undergoing renal tumor ablation under ultrasound guidance, CEUS may be used to improve lesion visualization in difficult cases and to detect residual tumor either immediately or later after ablation. When CEUS is planned, preablation assessment of lesion vascularity is important.

The size of solid renal tumors is a reliable factor in differentiating malignant from benign masses: tumors larger than 7 cm are malignant in 100% of cases whereas tumors less than 7 cm are 16% benign17 and those 4 cm or less are 20% benign.18 Tumors smaller than 1.5 cm may be controlled ( 9.4 g,h).

9.4 g,h).

The sonographic detection rate also depends on the tumor dimension: for tumors 10–15 mm in size it is 30%; at 20–25 mm, 80%, beyond that, 100%. The corresponding rates in CT are 70–100%.

353

9

Kidneys

The differential diagnosis of small, benign kidney tumors incorporates a large spectrum of focal lesions:

●Angiomyolipoma

●Oncocytoma

●Leiomyoma

●Focal xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis

●Hemangioma

●Complicated benign cyst

Nephroblastoma/Wilms tumor/cystic nephroma. A special type of renal tumor in children is the malignant nephroblastoma (Wilms tumor; see Table 9.7), which usually presents as a rapidly enlarging mass that becomes symptomatic. It shows a solid formation like the rare benign mesoblastic nephroblastoma, whereas the benign cystic nephroma shows multilocular fluid-filled cysts with vascularized septae (Fig. 9.72).

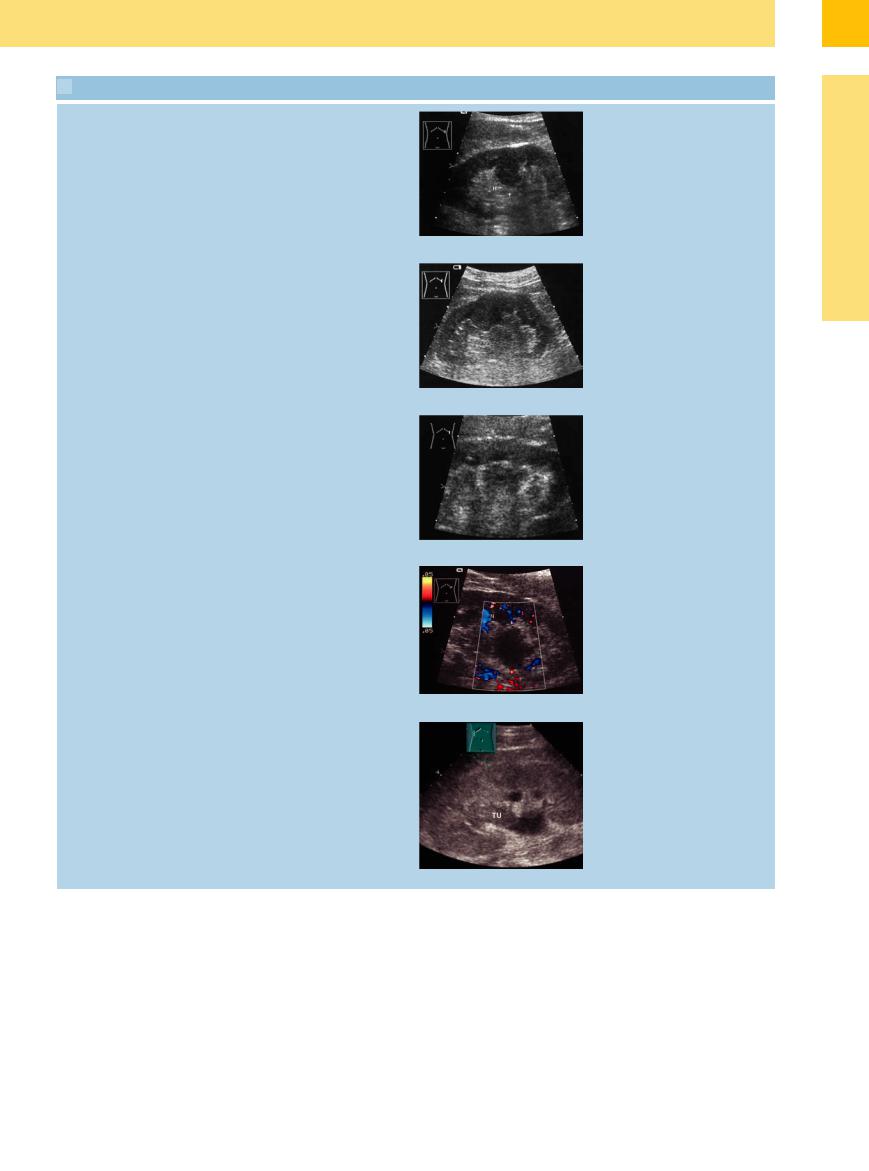

Fig. 9.72 Wilms tumor in an 18-month-old boy.19

a The left kidney shows a large well-defined and homogeneous echogenic mass (arrows) arising from the lower pole. Normal parenchyma is seen in the upper pole (UP).

c and d Multilocular cystic nephroma.

c Longitudinal scan of the left kidney shows numerous anechoic locules separated by echogenic septae.

b Contrast-enhanced CT scan confirms a large, intrarenal soft-tissue mass surrounded by enhancing parenchyma.

d Contrast-enhanced CT confirms a multilocular mass with enhancing septations replacing the renal parenchyma.

Urothelial Carcinoma

Carcinomas of the renal pelvis, ureter, and bladder differ fundamentally from renal tumors. They arise from the urothelium, or transitional epithelium, and occur as papillary and solid tumors. Renal pelvic carcinoma is three times more common than ureteral carcinoma. The tumor presents clinically with hematuria.

Urothelial carcinoma forms a hypoechoic, polypoid mass that fills the lumen of the renal

pelvis to produce a hypoechoic, butterfly-like figure. The tumor usually has a homogeneous echo texture, but the added presence of liquefied foci and calcifications give the tumor a inhomogeneous appearance. Unlike an infected obstruction and other masses in the central sinus echo complex, the tumor exhibits vascularity on color duplex examination. It is difficult to distinguish from RCC that has in-

vaded or displaced the renal sinus or renal pelvis ( 9.5e, see also Figs. 11.34, 11.35, 11.36).

9.5e, see also Figs. 11.34, 11.35, 11.36).

Given the major importance of hypoechoic masses in the renal sinus echo complex, the differential diagnostic features of these masses are reviewed in  9.5.

9.5.

Malignant Lymphoma

Another hypoechoic renal tumor is malignant lymphoma. It may occur either as a diffuse hypoechoic or heterogeneous mass (highgrade lymphoma) or as a smaller, circumscribed, round or oval tumor (renal involvement by low-grade lymphoma) (Figs. 9.32,

9.73, 9.79).

Fig. 9.73 |

b Probable high-grade malignant lymphoma, intra-ab- |

a Renal involvement by low-grade non-Hodgkin lym- |

dominal tumor dispersion: Atypical oval anechoic mass; |

phoma (cursors): elliptical hypoechoic tumor at the junc- |

clarification by CEUS or by follow-up under therapy. |

tion of the renal sinus and parenchyma. |

|

354

9.5 Differential Diagnosis of Hypoechoic Masses in the Renal Sinus Echo Complex

9.5 Differential Diagnosis of Hypoechoic Masses in the Renal Sinus Echo Complex

Renal column |

● |

Conical extension between the medullary |

|

|

pyramids |

|

● Isoechoic to the renal cortex |

|

|

● |

Normal vascularity |

Duplex kidney |

● |

Notch in the renal outline |

|

● |

Enlarged, elongated kidney |

|

● Normal echo structure (or hypoechoic with |

|

|

|

overlying parenchyma) |

|

● |

Normal vascularity |

|

● |

Duplicated renal pelvis |

● Duplicated ureters (visible only with obstruction)

Sinus lipomatosis |

● |

Hypoechoic, nodular mass with ill-defined |

|

|

margins |

|

● Confined to the sinus echo complex |

|

|

● Parenchymal–pelvic ratio shifted in favor of |

|

|

|

renal sinus |

|

● No vascularity in CDS |

|

|

● |

Bilateral |

Infected obstruction, abscess |

Infected obstruction |

|

|

● |

Hypoechoic to anechoic area conforming to |

|

|

the pyelocaliceal system and extending into |

|

|

the ureter |

|

● |

No vascularity |

Abscess, pyonephrosis

●Round or polygonal, nonhomogeneous mass, usually with ill-defined margins

●No vascularity

Urocelial carcinoma |

● |

Hypoechoic mass |

|

● |

Polygonal margins |

|

● |

Tumor vascularization |

a Hypertrophic renal column (C) next to large, hypoechoic medullary pyramids; renal transplant. NP = parenchyma.

b Tumor-like nub of parenchyma extending into the central echo complex.

c Hypoechoic tumor-like transformation of the sinus echo complex; no vascularity in the mass. N = kidney.

d Renal pelvic abscess: hypoechoic mass with ill-defined borders. Clinically, the patient had poorly controlled diabetes. N = kidney.

e Urocelial carcinoma (TU): hypoechoic mass in the central reflex invading the caliceal system; minimal obstruction.

9

Circumscribed Changes

355