- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

7

Gastrointestinal Tract

Tumor

Focal circular tumors of the gastric antrum, |

Fig. 7.23 Narrowing of the gastric lumen by an oblong |

|

body, and cardia as well as scirrhous carcinoma |

scirrhous carcinoma of the antrum, upper abdominal |

|

transverse scan. |

||

(Fig. 7.23) will lead to significant narrowing of |

||

|

||

the lumen, accompanied by dilatation of those |

|

|

segments of the stomach and/or esophagus up- |

|

|

stream. |

|

Postoperative Status

Depending on the degree of resection in stomach operations, the lumen of the gastric stump may be markedly smaller.

■ Small/Large Intestine

Small intestine. Ultrasonographic assessment of the jejunum and ileum is successful only if certain conditions are met. When differentiating sonographic findings of the small intestine, it is vital to know the time of the last ingestion. In a fasting patient these segments of the small intestine do not display a filled lumen, and unless there are pathological findings, such as ascites or inflammatory or neoplastic changes, this “empty intestine” is masked from the routine diagnostic ultrasonography. The only section of the small bowel regularly identified during ultrasound scanning is the terminal ileum where it crosses anterior to the psoas

muscle and where it terminates at the colon (ileocecal valve). Visualization and assessment of the jejunal and ileal loops can be facilitated and improved by examining the patient postprandially or after oral intake of fluid (with antifoaming agent added). Apart from a systematic analysis based on the above criteria, assessment profits from use of a 5 MHz probe since this allows better differentiation of the wall layers. In the visualization and assessment of peristaltic activity, no other abdominal organ, except the small bowel, has to rely so heavily on real-time scanning.

Colon. The large bowel frames the abdominal cavity. It is always filled to a varying degree by feces, scybala, and gas, thus being more of a hindrance for abdominal ultrasound scanning than offering easy access for diagnostic sonography. The physiological peristaltic movement of the colon cannot be visualized. The wall, lumen, and peristalsis can only be identified in large-bowel pathology or when employing special examination techniques (retrograde saline lavage, hydrocolonic sonography).

Focal Wall Changes

Tract |

|

|

|

|

|

Stomach |

|

Carcinoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Small/Large Intestine |

|

GIST |

||

|

|

|

|||||||

Gastrointestinal |

|

|

Focal Wall Changes |

|

Lymphoma |

||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Extended Wall Changes |

|

Appendiceal Mucocele |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dilated Lumen |

|

Hematoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Narrowed Lumen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Polyp |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intussusception |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foreign Object/Gallstone/Bezoar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diverticula |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diverticulitis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendicitis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hernia |

Focal wall changes at the small and large intes- |

the vicinity of this target sign as well, particu- |

||||||||

tine always present as a localized finding at the |

larly in those intestinal segments upstream of |

||||||||

intestinal loop itself. However, there will usu- |

the lesion. |

||||||||

ally be characteristic reactions and changes in |

|

|

|||||||

274

Carcinoma

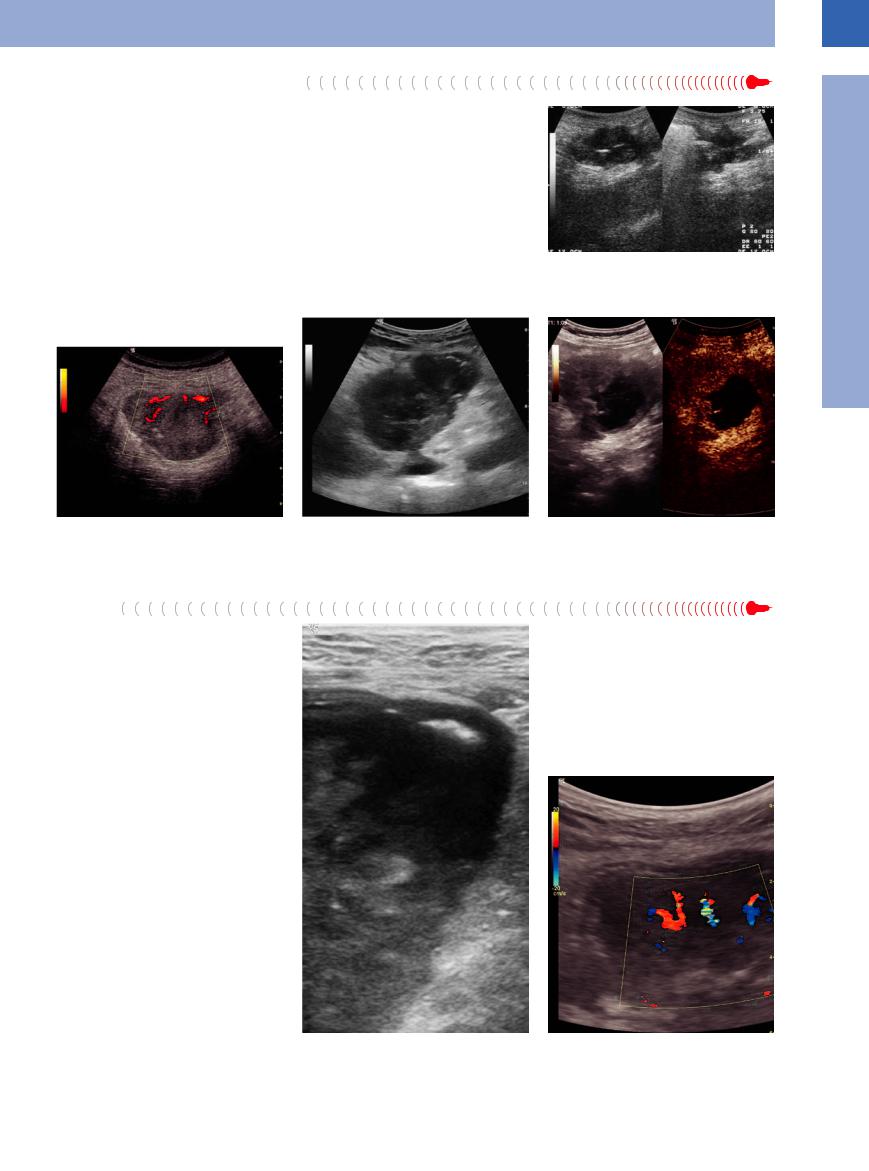

Focal adenocarcinoma is a common pathological finding in the large bowel, but it is a rare entity in the small intestine (Figs. 7.24, 7.25, 7.26, 7.27). Ultrasonography will demonstrate a typical concentric or atypical off-center target sign with loss of the normal wall layers. Irregular delineation at the luminal surface is not uncommon, and in concentric malignancies quite often the lumen will be narrowed. This stenosis may result in dilatation of the intestinal segments upstream, finally leading to fullblown ileus. The area around the neoplasm is

Fig. 7.25 Cancer of the colon in a polypoid tumor with pathologic tumor vessels.

characterized by a lack of peristaltic movement. The texture of the target sign is coarse, lacks pliability, and sometimes may be painful, signifying peritonitis.

The tumor may present a smooth or irregular surface, and in advanced stages free fluid and localized lymphadenopathy around the tumor may be demonstrated. Presently, there are no clear-cut color flow Doppler criteria characteristics of intestinal malignancy. These lesions are rather hypovascular in CEUS examinations, but relevant studies are lacking.

Fig. 7.26 Cancer of the colon with target sign, dorsally ascites by peritoneal carcinosis.

Fig. 7.24 Cancer of the small intestine.

Fig. 7.27 Tumor of the cecum: in CEUS, solid tumor formation, cystic/necrotic liquefaction.

GIST

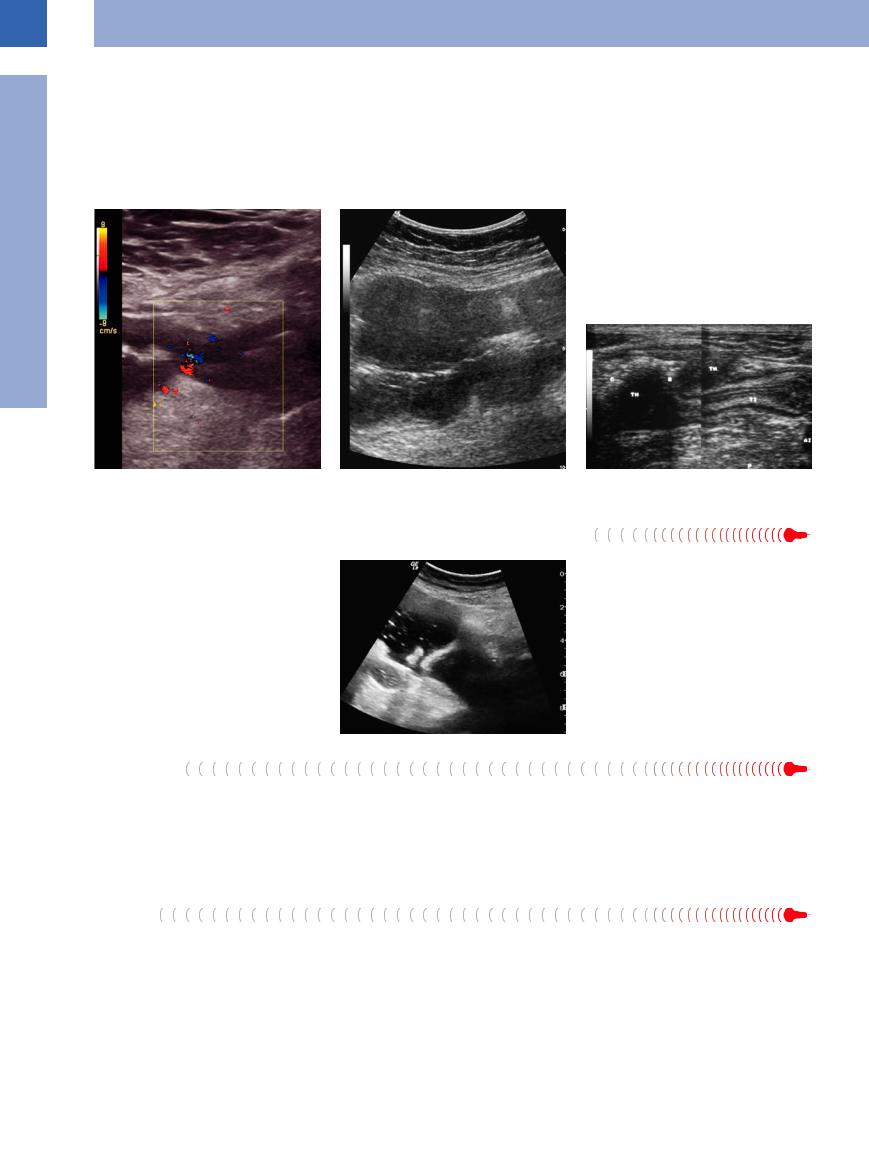

GIST is typically a hypoechoic mass with smooth margins. Up to a certain size these tumors are related to a layer in the wall of the small intestine (Fig. 7.28). With increasing size this relation is lost. GIST normally show a pronounced pathological vascularization (Fig. 7.29).

Fig. 7.28 GIST of the small bowel with enlarged intralumi- |

Fig. 7.29 GIST of the small bowel: intensive vascularization |

nal growth. |

of the prevailing indoluminal position. |

7

Small/Large Intestine

275

7

Gastrointestinal Tract

Lymphoma

Lymphoma of the small and large bowel |

zarre neoplasms with luminal stenosis are en- |

presents as a focal hypoechoic mass in the in- |

countered, which are difficult to delineate from |

testinal wall with loss of the normal layered |

the adjacent tissue and frequently are hyper- |

architecture (Figs. 7.30, 7.31, 7.32). Often bi- |

vascular. |

Fig. 7.30 Lymphangioma of the small bowel. |

Fig. 7.31 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the jejunum. |

Fig. 7.32 Lymphoma at the ileocecal valve in a patient |

|

|

with AIDS. |

Appendiceal  Mucocele

Mucocele

Cystic protrusions and mucinous-cystic tumors of the appendix are indications for surgery. They can be well delineated by ultrasound, and hydrocolonic sonography makes it possible to differentiate between different cystic masses in the right lower abdomen (Fig. 7.33).

Hematoma

Fig. 7.33 Demonstration of the cecal pole in hydrocolonic sonography: fluid-filled cecum with dilatation, thready connection to the balloon-like fluid-filled appendix (mucocele); posterior to the colon: normal ileum.

Sometimes coumarin anticoagulant therapy will be complicated by bleeding into the intestinal wall, leading to circular hypoechoic thickening of the wall or a focal hypoechoic mass, with subsequent narrowing of the lumen and loss of peristalsis.

Polyp

Polypoid changes of the intestinal wall are purely incidental findings best visualized when the lumen of the bowel contains only a trace of fluid (Fig. 7.35). Such a polyp will appear as a focal sessile protrusion into the in-

testinal lumen characterized by an atypical pathological gut signature. In larger polypoid lesions, color flow Doppler scanning may demonstrate the presence of vessels, thus permitting these neoplasms to be differentiated from

scybala. Polyps do not alter the outer margin of the intestinal wall. During peristaltic movement of the bowel, such a sessile polyp may be localized, but sometimes large polyps can induce intussusception.

276

Intussusception

In intussusception one part of the intestine prolapses along the longitudinal axis into an immediately adjoining part. Intussusception of early childhood, where the abnormal mobility of various intestinal segments will lead to the well-known enteric (Fig. 7.34) and ileocecal intussusception, has a different etiology from that in adults. In the latter case, there will always be a lead point triggering and leading the way for the prolapse. Such lead points include polyps (Figs. 7.35, 7.36, 7.37, 7.38), large mural lymph nodes, and tumors; in addition, intussusception may also arise in small bowel affected by Crohn disease.

Intussusception will present intermittently as a multilayered pathological gut signature or target sign. Edema and inflammation produce marked thickening, thus emphasizing the various layers of the wall, the outermost hypoechoic layer (muscularis propria) of the intus-

Fig. 7.34 Enteric intussusception.

susceptum being especially thick. The intussus- |

bowel loops are invaginated, the patient suffers |

ceptum can be identified by its own peristalsis, |

from massive localized pain and tenderness. |

and in adults a tumorous lesion (polyp, tumor, |

|

lymph node) will provide the lead point. When |

|

7

Small/Large Intestine

Fig. 7.35 Intussusception. Left: longitudinal view with muscular hypertrophy in the thickened outer and delicate invaginated inner gut signature. Right: cross-sectional view of a polyp as the leading point.

Fig. 7.36 Jejuno-jejunal short-segmental intussusception in Crohn disease.

a Transverse scan.

b Longitudinal scan.

Fig. 7.37 Ileocecal intussusception: demonstration of vascularity (CDS).

fFig. 7.38 Intussusception of the ileocecal valve into the cecum in the case of an enteritis; this may regress and occurs also in the preparation for a saline lavage.

277

7

Gastrointestinal Tract

Foreign Object/Gallstone/Bezoar

Large foreign objects may impact in the small |

men of the small intestine it will be visualized |

logical findings can be demonstrated at the |

bowel, thus producing localized reaction and |

as a ball-shaped, inhomogeneous hyperechoic |

gallbladder and possibly the biliary tree (pneu- |

even triggering mechanical ileus. The most |

mass with posterior shadowing. There is very |

mobilia). Other foreign objects such as probes |

common such object is a large gallstone that |

little localized tenderness and the findings and |

(gall drainage) which are placed intervention- |

has perforated the gallbladder into the duode- |

symptoms of the mechanical ileus dominate |

ally by operation or endoscopy usually relocate |

num (Fig. 7.39, Fig. 7.40). If it obstructs the lu- |

the picture. In addition, unequivocally patho- |

naturally into the intestine (Fig. 7.41, Fig. 7.42). |

Fig. 7.40 Surgical specimen after the operation for a gallstone ileus.

Fig. 7.39 Gallstone impacted in the jejunum. |

Fig. 7.41 Foreign body in a small bowel loop after a |

|

Whipple operation, demonstration with a 3.5 MHz convex |

|

array. |

Diverticula

Besides the typical clinical findings, ultrasound has become the most important method for the diagnosis of diverticulitis, providing a sensitivity of 98.1% and a diagnostic accuracy of 97.7%.

Diverticula of the sigmoid colon are echogenic because of the gas or feces they contain; sometimes the outer hypoechoic layer of the intestinal wall (muscularis propria) becomes more pronounced owing to the concurrent muscular hypertrophy.

At times, duodenal diverticula (Fig. 7.43, Fig. 7.44) may be recognized at the papilla by the manifestation of indirect signs such as dilation of DP and/or DHC and by the alternating presence of air and fluid within the lumen. A malignant mass has to be excluded (by CEUS). However, Meckel’s diverticulum may only be visualized in the presence of pathological changes.

Fig. 7.43 Visualization of a periampullary duodenal diverticulum filled with air.

Fig. 7.44 Parapapillar duodenal diverticula with dilated pancreatic and common bile duct.

Fig. 7.42 Foreign body in a small bowel loop after a Whipple operation, demonstration with 9 MHz array.

278

Diverticulitis

Inflammation of a diverticulum will always result in localized tenderness. The diverticulum itself displays marked distension; the diverticular wall will appear as an edematous, hypoechoic, crescent-shaped halo around the lumen which, when filled with feces, will be hyperechoic or hypoechoic in the presence of fluid (Fig. 7.45).

Apart from this typical local finding, diverticulitis will demonstrate two other characteristic findings: particularly proximal of the diverticulum, the intestinal loop shows extended muscular hypertrophy of the wall and thicken-

ing of the outermost hypoechoic layer, as well as edema with pronounced layering of the wall and marked narrowing of varying degree of the gut lumen. There will be significant inflammatory hypervascularity at the diverticulum, which is surrounded by a localized massive reaction of the adjacent tissue: its being walled off by the greater omentum may result in a hyperechoic halo several centimeters thick. Complications are heralded by peridiverticular fluid, local collection of gas, abscess formation, and fistulization ( 7.2).

7.2).

Fig. 7.45 Diverticulitis. Indicating sign is the extensive edematous pathological gut signature in the left lower quadrant with muscular hypertrophy of the intestinal wall and narrowed lumen.

Diverticulosis/Diverticulitis

True diverticula are sacculations of the intestinal wall involving all layers and resulting in localized outpouching, e. g., duodenal diverticula (Fig. 7.43), Meckel’s diverticulum, diverticula of the ascending colon. However, false diverticula, also known as pseudodiverticula, are by far more frequent: here, gaps (defects) in the muscularis propria lead to localized sacculation of mucosa and submucosa (e. g., sigmoid diverticula). Local findings always include hyperplasia of the muscularis propria, and the

musculature of the surrounding intestinal wall becomes hypertrophied. The formation of numerous pseudodiverticula in the sigmoid colon (diverticulosis) is seen as a sequela of local pressure increases within the intestinal lumen, which in turn arises from nutrition low in dietary fiber. In addition, focal weakening of the bowel wall around the afferent and efferent vessels is also considered a causative factor. Feces impacted and inspissated in the extruded diverticular sac induce local pressure ero-

sion of the mucosa, chronic inflammatory granulation (diverticulitis), and also possibly abscess formation and perforation ( 7.2). Apart from muscular hypertrophy of the intestinal wall (particularly of the proximal segments), recurrent and chronic inflammation with edema and narrowing of the lumen will finally result in cicatricial contraction of the chronically inflamed bowel segment.

7.2). Apart from muscular hypertrophy of the intestinal wall (particularly of the proximal segments), recurrent and chronic inflammation with edema and narrowing of the lumen will finally result in cicatricial contraction of the chronically inflamed bowel segment.

7.2 Acute Sigmoid Diverticulitis

7.2 Acute Sigmoid Diverticulitis

7

Small/Large Intestine

a Sigmoid with slight hypertrophy of the colonic wall and detection of a gas-filled diverticulum; no pain at palpation, no panniculitis.

e and f Demonstration of inflammatory hypervascularity.

e Normal color Doppler.

b Perforation with demonstration of free c and d Walled-off perforation with localized collection of free air and free fluid. fluid and abscess formation: hyperechoic

panniculitis.

f Power Doppler. |

g Differential diagnosis to acute diverticulitis: appendicitis. Immediately |

|

next to the thickened gut sign of the sigmoid (right side) there is a localized hypoechoic |

|

area (pain at palpation) corresponding to an ischemic epiploic |

|

appendix. No panniculitis. |

279

7

Gastrointestinal Tract

Appendix

An experienced examiner can visualize a normal appendix with high-resolution probes in approximately 70% of cases; a gut signature displaying normal architecture will be seen at the cecum, terminating blindly and lacking in peristalsis, with a maximum diameter in excesss of 6 mm (Fig. 7.46).

Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis can be diagnosed sonographically with a positive predictive value of 95.7% and a sensitivity of 88.5%. Thus, the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound is only marginally less than that of bolus CT (sensitivity 96%, positive predictive value 95–96%). Inflammation of the appendix is characterized by enlargement, dilatation, and thickening, initially with demonstration of edema and accentuated layering of the wall; quite often fecaliths will be seen within the lumen. Appendicitis is always accompanied by localized tenderness (Figs. 7.47, 7.48, 7.49). Advanced stages will destroy the layered structure of the wall and produce a hyperechoic echo, local accumulation of fluid, and abscess formation (Table 7.4, Fig. 7.50). In such an advanced stage of the inflammation, the appendix itself is almost im-

possible to identify, and frequently localized lymphadenopathy will be evident.

Table 7.5 summarizes the differential diagnosis of appendicitis by ultrasound (Fig. 7.51).

Table 7.4 Sonographic signs in acute appendicitis

●Swelling of the appendix

●Thickening of the wall

●Fluid-filled lumen

●Tenderness

●Fecalith

●Hyperechoic omental cap

●Free fluid

●Perityphlitis

●Loss of peristalsis

Table 7.5 Differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis by ultrasound

Bowel |

● Enteritis |

|

● Terminal ileitis |

|

● Intussusception |

|

● Diverticulitis |

|

● Tumor |

Adnexa and ovary |

● Adnexitis |

|

● Tubo-ovarian abscess (Fig. 7.51) |

|

● Ectopic pregnancy |

|

● Hemorrhagic cyst |

|

● Torsion of ovarian tumor |

Psoas muscle |

● Hematoma of the psoas muscle |

Ureter |

● Stenotic ureteral origin |

|

● Ureterolith |

Lymph node |

● Mesenteric lymphadenitis |

Vessels |

● Thrombosis |

|

● Arterial dissection |

|

● Aneurysm |

Other |

● Cholecystitis |

|

● Pancreatitis |

|

● Perforated gastric ulcer |

Fig. 7.46 Normal appendix in free fluid collection.

Fig. 7.47 Acute appendicitis. Pathologically distended and thickened appendix (12 mm) with blurred wall layering, local tenderness; posterior echogenic panniculitis.

Fig. 7.48 Acute appendicitis. Thick pathological gut signature with barely visible wall layering.

280

7

Small/Large Intestine

Fig. 7.49 Acute appendicitis. Thick pathological gut sig- |

Fig. 7.50 Perforated acute appendicitis. |

nature with accentuated wall layering, inflammatory hy- |

|

pervascularization, posterior hyperechoic halo, anterior |

|

free fluid. |

|

Hernia

Hernias are defects in the abdominal wall. Ultrasound can identify the location (inguinal, femoral, umbilical, incisional, spigelian, epigastric) and size of the fascial defect as well as the contents. Demonstration of an edematous gut signature with accentuated wall architecture in the hernial sac proves that bowel is involved in the herniation; in these cases, stasis and even mechanical ileus may be present in the more proximal intestinal segments (Figs. 7.52, 7.53, 7.54).

Fig. 7.51 Differential diagnosis for acute appendicitis: purulent salpingitis.

Fig. 7.52 Hernia.

Fig. 7.53 Inguinal hernia on the left with incarcerated intestinal loop and mechanical ileus.

Fig. 7.54 Umbilical hernia.

a Scan showing an incarcerated intestinal loop (circular folds).

b CDS: preserved vascularization of the hernial content.

281