- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

1

Vessels

Intraluminal Mass

Vessels |

|

|

Aorta, Arteries |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Vena Cava, Veins |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Anomalies |

|

|

|

|

Dilatation |

|

|

|

|

Intraluminal Mass |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compression, Infiltration |

Venous Thrombosis

Phleboliths, Calcification

Venous Valves

Venous Thrombosis

The value of diagnostic ultrasound. Today, ultrasonography is the modality of choice in case of suspected thrombosis, and together with phlebography it has become the gold standard in the diagnosis of venous thrombosis. Colorflow Doppler scanning demonstrating little or no flow has expanded its diagnostic capabilities. Sonographic work-up for suspected venous thrombosis of easily accessible regions may be performed without difficulty and takes only a few minutes. It is more difficult to perform on the iliac veins, the lower leg, the periuterine venous plexus, or the ovarian vein, where it has a higher error rate. The sensitivity is 91%, the specificity 96%.

Phlebography only becomes necessary in case of strong clinical suspicion, if the diagnostic findings are negative or ambivalent, or if the conditions for the study are especially poor. Reliable sonographic diagnosis of venous thrombosis is even possible in the lower leg, although here usually only the posterior tibial veins can be imaged.

Venous filling. There may be problems if the deep veins are not sufficiently filled, particularly in hypovolemia, in which case it may be helpful to evaluate the patient standing and

with compression of the lower leg. On the other hand, marked venous engorgement will complicate the evaluation since the deep veins will come under pressure and this may mimic incompressibility.

Criteria of thrombosis. The surest sign of thrombosis is venous incompressibility. It is not possible to differentiate between old and fresh thrombi. A free-floating thrombus tail surrounded by blood flow, identification of the thrombus head, and discrete compressibility of the thrombus indicate a soft thrombus. A normal venous lumen is seen only in old thrombosis. Extrinsic compression of the vein with the probe could shear off the thrombus in rare cases but would not result in any clinically evident embolism.

Ultrasonography of a thrombus surrounded by blood demonstrates an anechoic marginal lumen between thrombus and venous wall, the flow being confirmed by color-flow Doppler scan. Color-flow duplex evaluation is of vital importance for this type of thrombosis as well as for difficult sonographic conditions. Even if the vein is hardly visible in B-mode imaging, thrombosis can be definitively ruled out by color-flow duplex scanning. Compression ul-

trasonography is best suited for evaluating the treatment, making phlebographic controls unnecessary. There is no formal distinction between plateletand tumor-induced thrombosis.

1.5 gives examples of the sonographic criteria of thrombosis after Habscheid15 (also see Fig.1.13, Fig.1.65).

1.5 gives examples of the sonographic criteria of thrombosis after Habscheid15 (also see Fig.1.13, Fig.1.65).

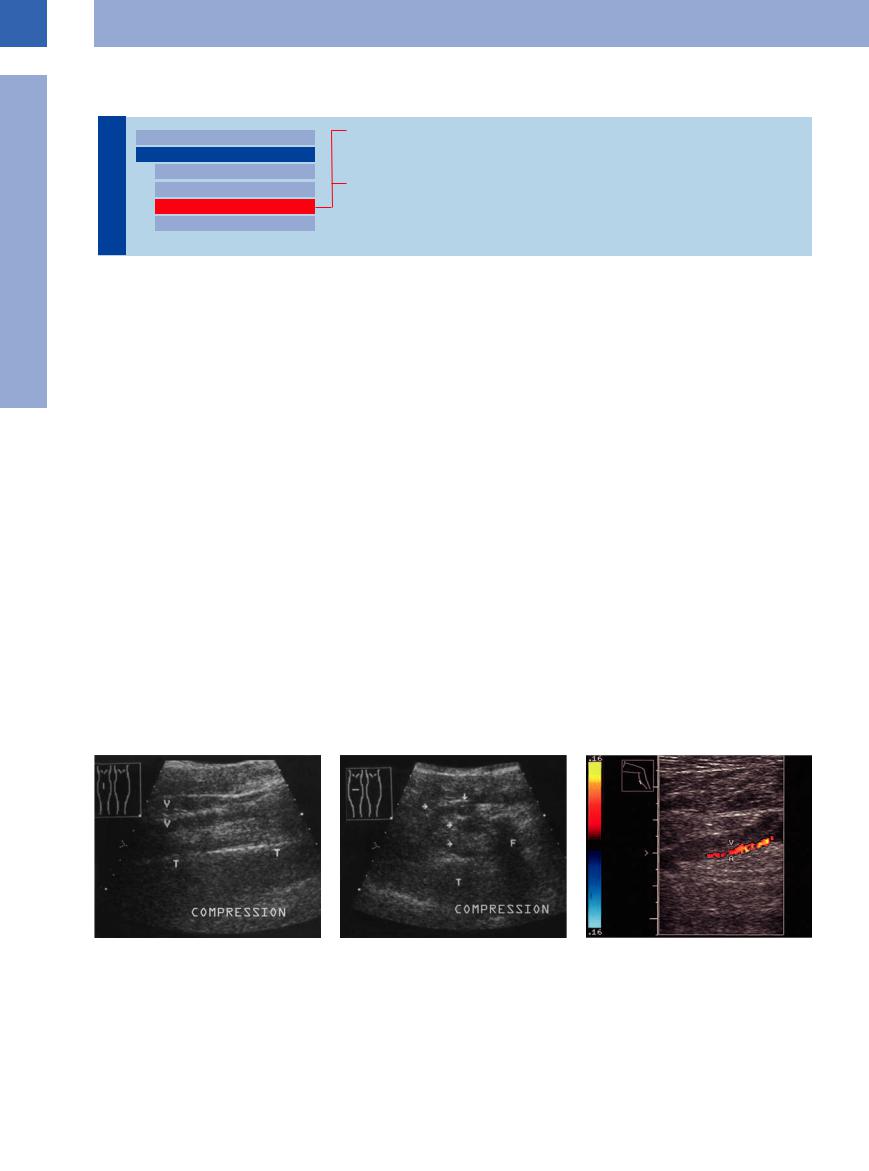

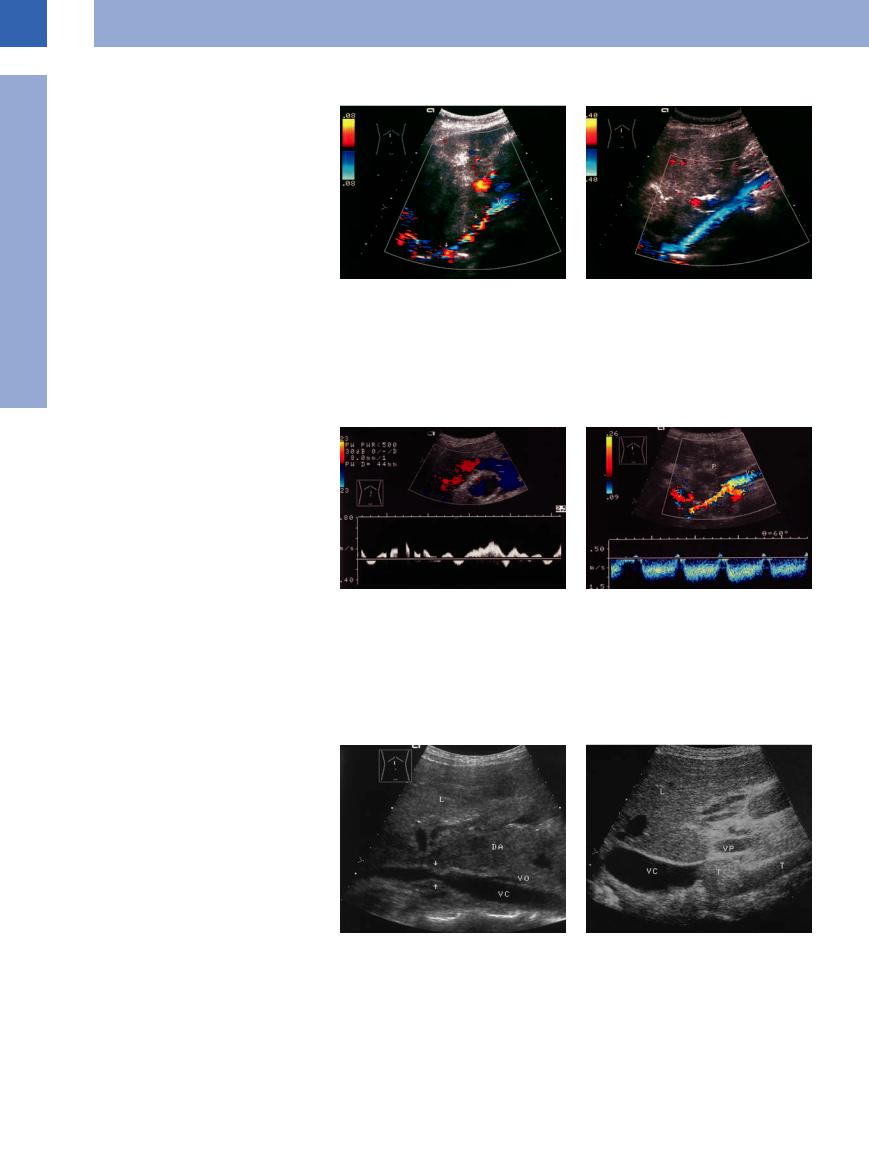

Crural thrombosis. Venous thrombosis in the calf is more difficult to image because the deep posterior tibial veins are hard to insonate, especially in hypovolemia and dialysis. In this case the lack of demonstrable veins almost rules out venous thrombosis since the latter would have resulted in easily viewed engorged veins (Fig.1.70).

Superficial venous thrombosis. Just as for the deep veins, superficial venous thrombosis fulfills the same typical sonographic criteria. In thrombosis of the greater and lesser saphenous vein, always insonate the saphenofemoral and saphenopopliteal junctions, respectively, to check the passage into the deep vein (Fig.1.71, Fig.1.72).

Fig. 1.70 Deep venous thrombosis of the calf affecting the posterior tibial group of veins (V, arrows). F = fibula; T = tibia.

a Longitudinal view of the calf.

b Transverse view of the calf: incompressible veins (arrows).

c Deep venous thrombosis of the calf, color-flow Doppler scan: enlargement of the vein (V) compared with the artery (A). Incompressibility.

34

1.5 Sonographic Criteria for Assessing Venous Thrombosis

1.5 Sonographic Criteria for Assessing Venous Thrombosis

Incompressibility (most important sign)

Vascular enlargement (1.5 × arterial diameter)

Intraluminal echogenic structures

No Doppler signals and flow or flow defects in color-flow Doppler scanning

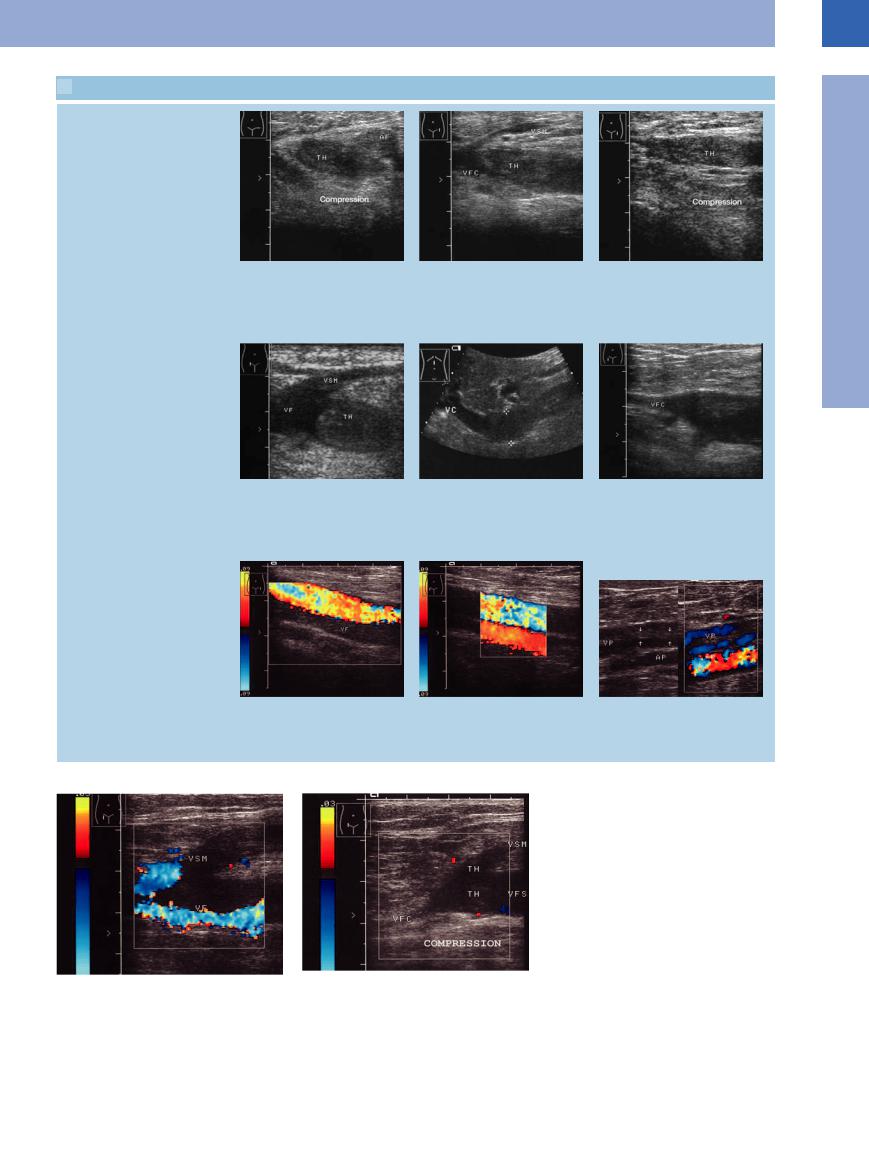

a–c Deep venous thrombosis (TH) of the thigh.

a Cross-section: this view permits better detection of the vein, which cannot be compressed because of the thrombosis.

d Fresh venous thrombosis (TH), such as is imaged here, will always enlarge the diameter of the vessel. The lumen of the vein will remain normal only in cases of old thrombosis (g). VF = femoral vein; VSM = greater saphenous vein.

g and h Old thrombosis of the femoral vein (VF) in color-flow Doppler scanning. g Since the vein is not dilated, there is no initial suspicion of thrombosis; no flow in color-flow duplex scanning.

b Longitudinal view: presentation of the patent proximal segment of the common femoral vein (VFC) as well as the thrombus (TH). The greater saphenous vein (VSM) is slender with no suspicion of thrombosis.

e Thrombosis of the vena cava (VC): localized engorgement of the vena cava (calipers). The thrombus itself hardly has any structural elements and therefore cannot be seen directly.

h For comparison, the right femoral vein, which is not thrombosed.

c Compression: under extrinsic compression there is complete collapse of the proximal femoral and the greater saphenous veins, while the thrombosed section is incompressible.

f Thrombosis of the common femoral vein (VFC): markedly dilated segment of the vein at the partial thrombosis (echogenic structures).

i Partial thrombosis of the popliteal vein (VP). B-mode image: central thrombosis (arrows) of the vein. In color-flow Doppler imaging there is marginal flow. AP = popliteal artery.

Fig. 1.71 Deep thrombosis of the superficial femoral and greater saphenous veins.

a No flow in the greater saphenous vein (VSM), with some flow in the superficial femoral vein (VF).

b Compression: the remaining perfusion is blocked, while the thrombus (TH) is incompressible.

1

Vena Cava, Veins

35

1

Vessels

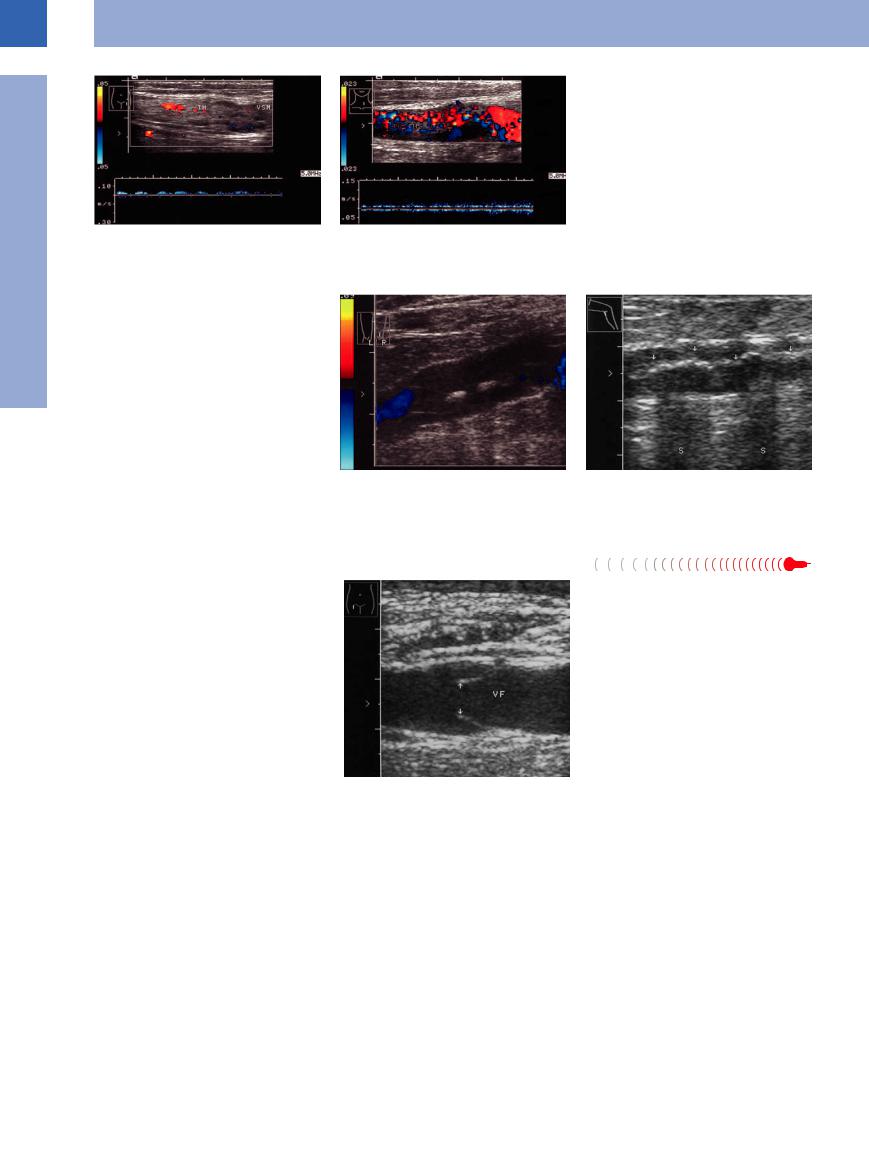

Fig. 1.72 Superficial venous thrombosis (TH).

a Thrombosis of the greater saphenous vein (VSM). Distended lumen, echogenic structures, low-level perfusion, spectral analysis.

b Intensive spotty vascularization within a thrombus in the jugular vein: tumorous thrombus originating from thyroid metastasis of renal carcinoma.

Phleboliths, Calcification

Phleboliths (also known as “vein stones”) are calcified thrombi and appear as hyperechogenic masses, sometimes associated with shadowing. They may occur in focal fashion or as extended horseshoe-shaped calcifications, resulting in a bandlike structure within the vein with strong reflections (Fig.1.73, Fig.1.74).

Fig. 1.73 Phleboliths with incomplete shadowing in a |

Fig. 1.74 Old calcified band-shaped thrombosis of the |

superficial vein of the calf, old thrombosis, flow defect |

lesser saphenous vein, shadowing (S). |

in color-flow Doppler scanning. |

|

Venous Valves

Venous valves are pocket-shaped intimal folds with check valve characteristics, permitting blood flow only toward the heart. Under excellent sonographic conditions they may be imaged as echogenic V-shaped intraluminal structures opening toward the heart (Fig.1.75).

Fig. 1.75 Venous valves (arrows) within the femoral vein (VF).

36

Compression, Infiltration

Vessels |

|

Lymph Nodes, Cysts |

|

Aorta, Arteries |

Enlarged Caudate Lobe |

|

Vena Cava, Veins |

Budd–Chiari Syndrome/Veno-occlusive Disease |

|

Anomalies |

|

|

Dilatation |

Other Masses |

|

Intraluminal Mass |

|

|

Malignant Tumor |

|

|

Compression, Infiltration |

|

|

|

|

Enlarged Caudate Lobe |

|

|

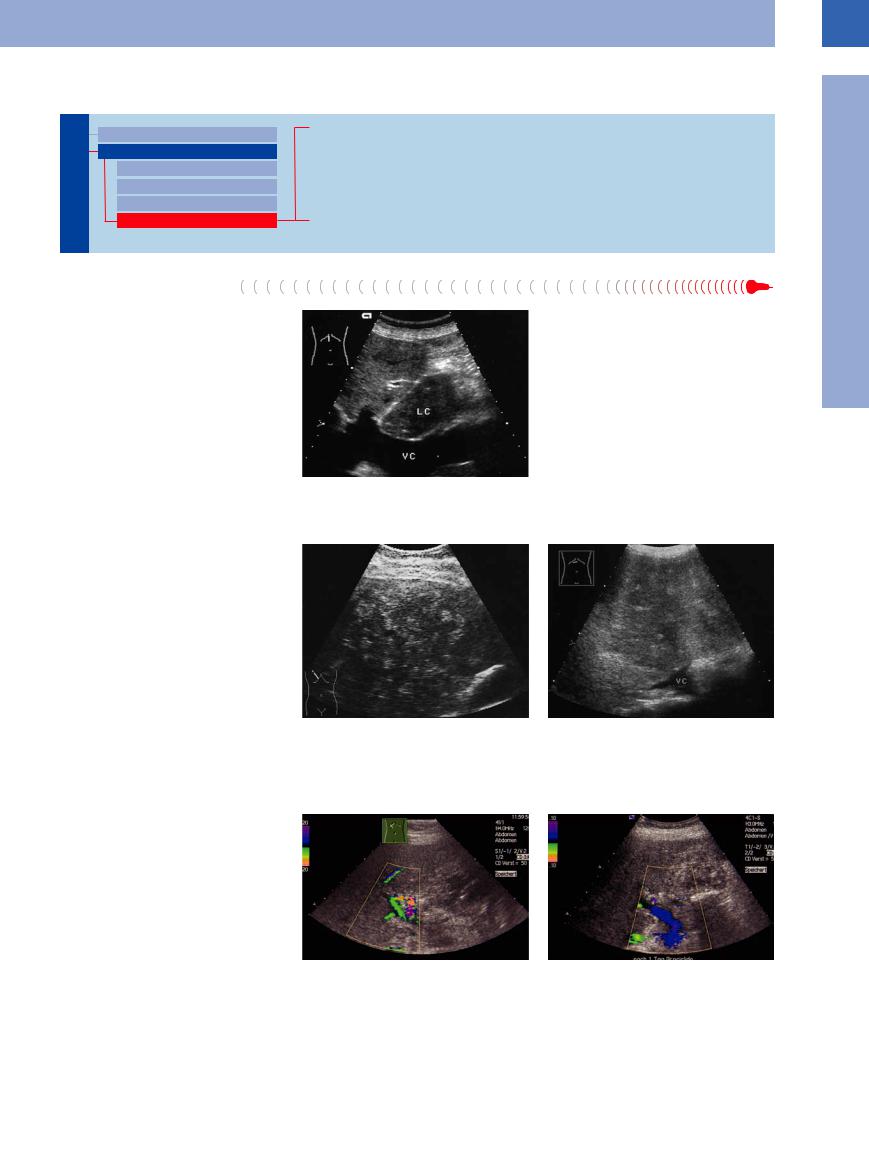

The inferior vena cava arcs widely posterior to |

Fig. 1.76 Cirrhotic enlargement of the caudate lobe (LC): |

|

the caudate lobe. Because of this close anatom- |

impressed and displaced vena cava (VC). |

|

ical relationship, it is more (tumorous infiltra- |

|

|

tion) or less (long arced impression in case of cirrhotic enlargement of the caudate lobe) involved in any adjacent changes (Fig.1.76).

Budd–Chiari  Syndrome/Veno-occlusive Disease

Syndrome/Veno-occlusive Disease

The most severe, and without treatment lethal, effect on the inferior vena cava is Budd–Chiari syndrome with thrombosis of all hepatic veins (young women on oral contraceptives) or tumorous occlusion (older patients with infiltration of the inferior vena cava at the junction of the hepatic veins). Ultrasonography, in particular color-flow duplex scanning with spectral analysis, is the imaging modality of choice in the diagnosis of a thrombotic or tumorous occlusion of the hepatic veins. It may also aid in the rapid diagnosis of the cause of lower venous congestion (as well as upper, e. g., with local metastasis of lung cancer).

Veno-occlusive disease (VOD). At diminished filling of the great liver veins the VOD is only indirectly detectable on a flow arrest or reversal flow of the portal vein (mostly caused by hematological diseases) (Fig.1.77).

Fig. 1.77 Acute and chronic Budd–Chiari syndrome.

a Acute Budd–Chiari syndrome: occlusion of all three hepatic veins (infiltration of the vena cava by metastatic lymph nodes). Speckled liver structure, no visible veins. Clinical diagnosis was ovarian cancer; there was massive pain and the patient died after a few days.

b Chronic Budd–Chiari syndrome: Diffuse metastatic infiltration with occlusion of the liver veins. VC = vena cava.

c Veno-occlusive disease |

(VOD) in acute myeloid leuke- |

d Regular flow (lilac–blue coded) after 1 day defibrotide |

mia and allogenic bone |

marrow transplantation. Flow |

(Prociclide). |

arrest/reversed flow in the region of the portal vein, |

|

|

green–lilac–yellow coded. |

|

|

1

Vena Cava, Veins

37

1

Vessels

Lymph Nodes, Cysts

Cysts

Compression of the vena cava and peripheral veins by lymph nodes and cysts is quite common. Because of their thin walls and low blood pressure, veins will yield to the pressure of an extrinsic mass and become indented according to its shape. The type of mass may be diagnosed on the basis of the patient’s history and clinical symptoms, and occasionally by ultra- sound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

Malignant lymphomas tend to present as extended mass encasing arteries and veins; they are thus associated with compression and displacement rather than infiltration (Fig.1.78).

Fig. 1.78 Tumor compression and infiltration of the vena cava (VC, arrows) by metastasis of a colorectal carcinoma in the caudate lobe.

a Image shows an irregular high-grade stenotic vena cava with turbulence-induced color change (blue–yellow–red, CDS).

b Three months later, after chemotherapy: regression of the infiltration and restored laminar flow.

Other Masses

Retroperitoneal fibrosis is another, but rather uncommon, cause of impression of the vena cava. Aortic aneurysm or enlargement of the pancreatic head may also displace or severely compress the vena cava (Fig.1.79, Fig.1.80).

Fig. 1.79 Severe curved displacement of the vena cava by |

Fig. 1.80 Compression of the vena cava by the enlarged |

an aortic aneurysm: spectral analysis depicts the normal |

pancreatic head in an acute attack of chronic pancreatitis. |

venous Doppler spectrum with cardiac modulation. |

The vena cava (VC) is markedly narrowed. Abnormal |

|

spectral waveform shows stenotic flow acceleration and |

|

a pulsatile flow pattern. P = pancreas. |

Malignant Tumor

Malignant tumors tend to infiltrate, whereas metastases compress. In both cases the end result may be occlusion of the vena cava with its prognostically poor sequelae (Fig.1.81,

Fig.1.82, Fig.1.97).

Fig. 1.81 Severe infiltration of the vena cava (arrows) by the caudate lobe metastasis of breast cancer. DA = small bowel; VO = ovarian vein; VC = vena cava; L = liver.

Fig. 1.82 Renal cell carcinoma. Upper abdominal longitudinal scan of tumor (T) infiltrating the vena cava (VC). L = liver; VP = portal vein.

38