- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

11

Urinary Tract

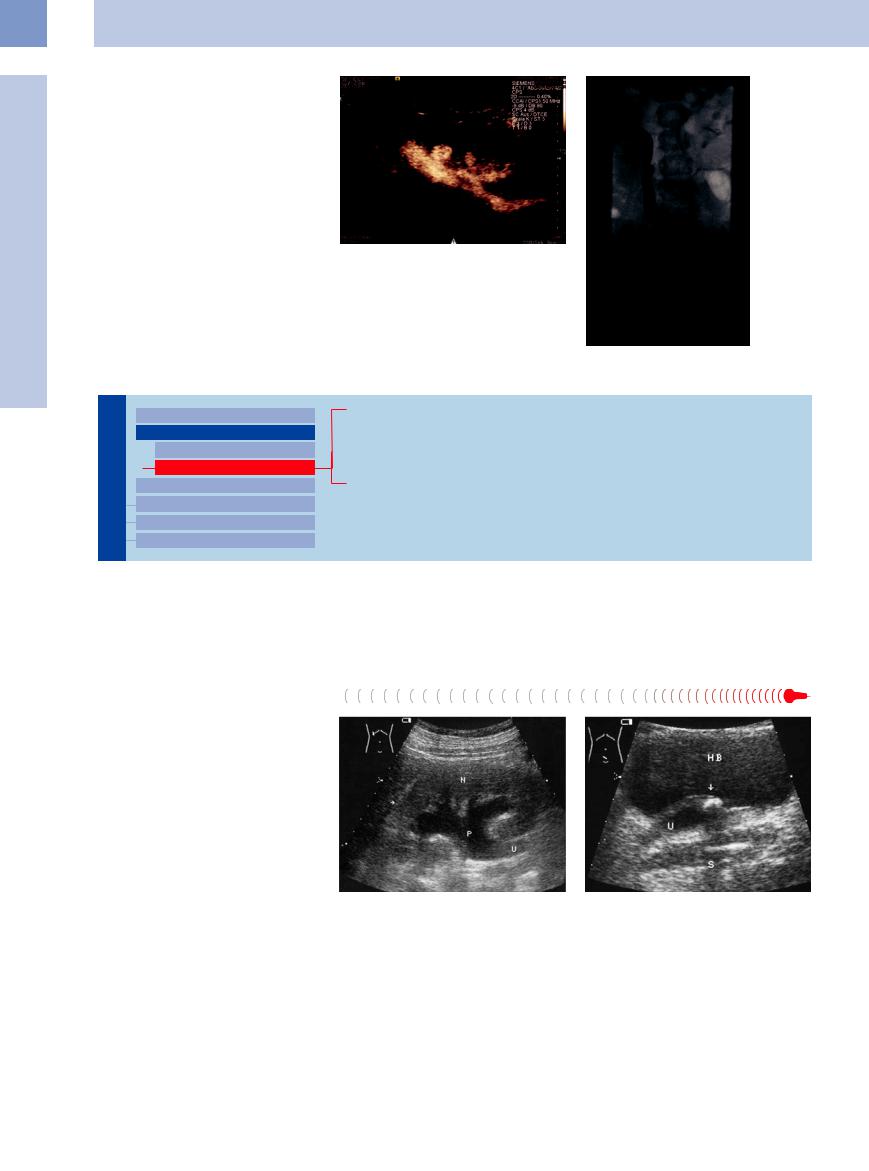

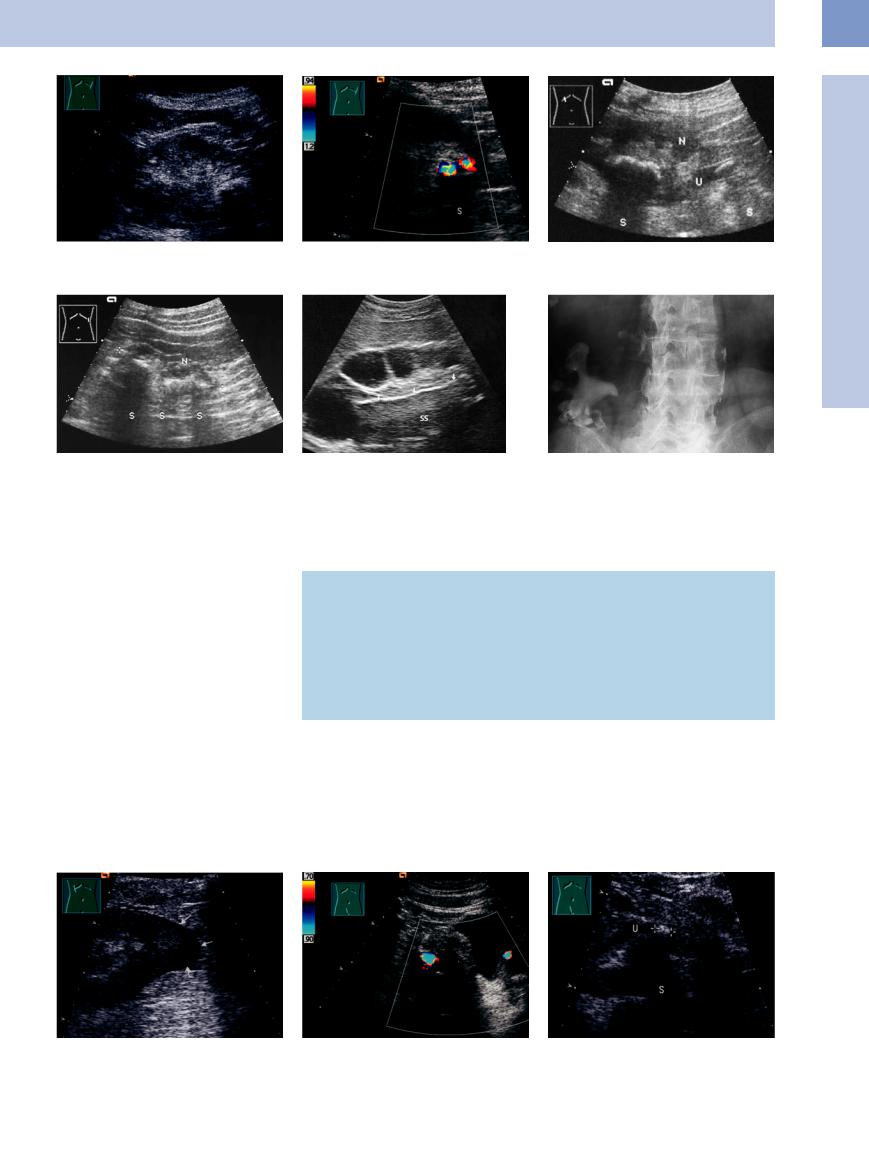

become a routine option that can completely replace reflux examinations using ionizing radiation (i. e., voiding cystourethrography) in girls (boys after conservative or operative therapy) and for screening high-risk patients for reflux. Comparative studies of voiding urosonography and cystourethrography have shown significantly higher sensitivity for urosonography in detecting reflux (Fig.11.30).

Fig. 11.30 Vesicoureteral reflux (images courtesy of Professor V. Klingmüller, University of Marburg, Germany). a CEUS after introduction of contrast agent into the bladder: enhancement within the renal pelvis and ureter.

b Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). Reflux into the renal pelvis.

Hypoechoic

Urinary Tract

Malformations

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter Anechoic

Hypoechoic

Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass Changes in Bladder Size or Shape Intracavitary Mass

Wall Changes

Hemorrhage (Traumatic, Clot)

Infected Obstruction

Suppurative Pyelitis

Pyonephrosis

Hemorrhage (Traumatic, Clot)

(Traumatic, Clot)

Traumatic or postprocedure hemorrhages |

in |

the features of fluid-related pyelectasis. The |

echogenic and show nondirectional flow with |

|

the |

kidney appear as hypoechoic masses |

in |

cause in most cases can be determined clini- |

turbulent zones on color Doppler. |

the |

renal pelvis and ureter or may produce |

cally (see Fig.11.38). Fresh hemorrhages are |

|

|

Infected Obstruction

If a patient with renal stone colic becomes febrile, an infected obstruction should be suspected. Urinalysis will show signs of a urinary tract infection. Not every infected obstruction is preceded by stone colic, but an obstructive, septic urinary tract infection should be considered in patients who present with unexplained fever. This is especially likely in older patients with impaired host resistance and in patients with poorly controlled diabetes.

Ultrasound often shows only a hypoechoic or largely anechoic dilatation of the pyelocaliceal system. A stone is frequently but not always detectable. If the obstruction can be visualized, it may appear as a hyperechoic mass in the renal pelvis (staghorn calculus), in the ureter (ureteral stone), or at the vesical or infravesical level (tumor, reflux, or prostatic hyperplasia, which is bilateral). For this reason, the sonographic investigation of fever should always include a detailed inspection of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (Figs. 11.31, 11.32, 11.33).

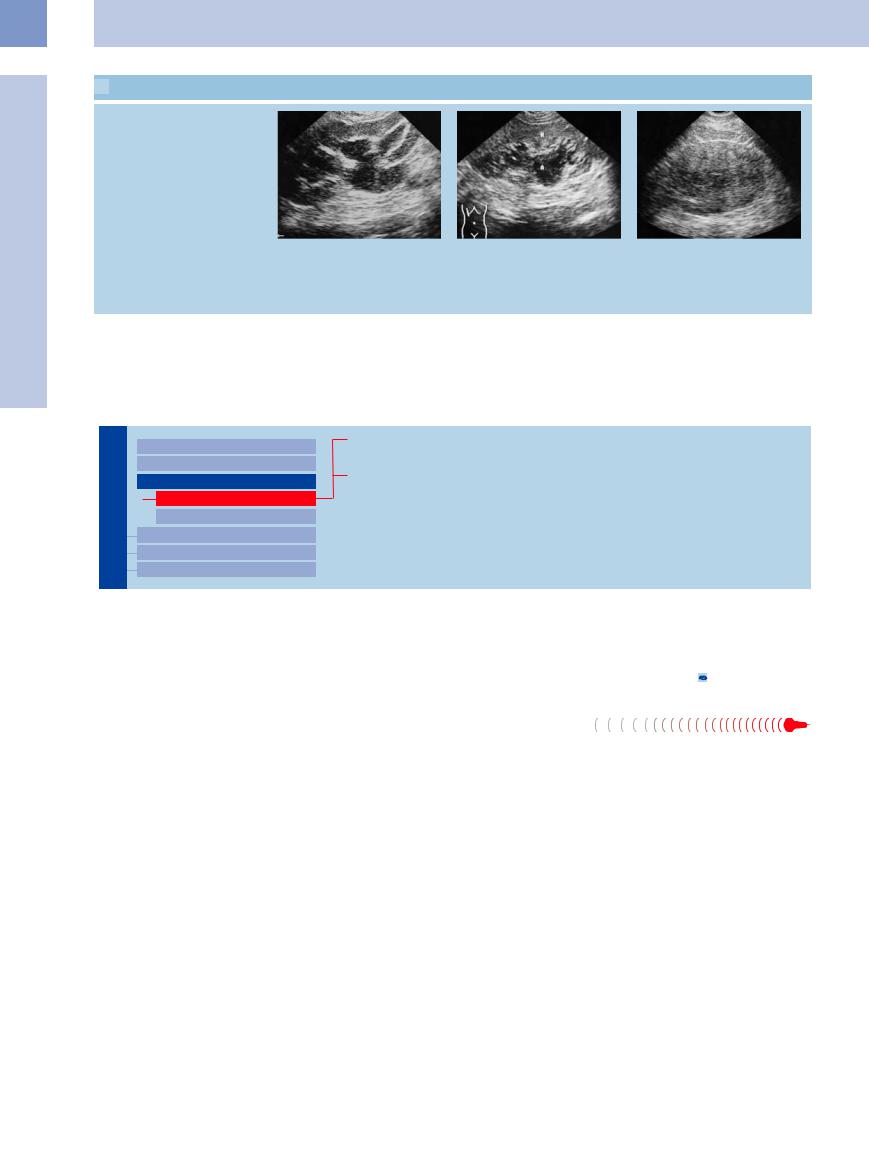

Fig. 11.31 Infected obstruction in association with a prevesical stone; septic temperatures.

a Grade I urinary stasis. The renal pelvis (P) and ureter (U) are not entirely anechoic. N = kidney.

Even if a stone is not detected and there is no ureteral dilatation, the mere suspicion of an infected obstruction warrants intervention in order to prevent urosepsis.

b Prevesical obstructing stone (arrow, acoustic shadow S). HB = bladder.

392

Fig. 11.32 Infected obstruction: anechoic to hypoechoic, |

Fig. 11.33 Infected obstruction in association with sub- |

poorly marginated dilatation of the pyelocaliceal system |

pelvic ureteral stenosis. |

(P) and ureter (U). N = kidney. |

a Hypoechoic, obstructed pelvis with sonographically in- |

|

distinct margins. |

Suppurative Pyelitis

Suppurative pyelitis is a pyelonephritis that has developed by the ascending route and predominantly affects the renal pelvis. Obstruction may be present or absent. Unlike pyelonephritis that arises by the hematogenous route, the findings are concentrated in the renal pelvis and consist of an anechoic mass that is clearly definable with ultrasound. Suppurative pyelitis

may result from an obstruction to urine outflow such as a congenital malformation, prostatic hyperplasia, or urolithiasis, or there may be factors predisposing to infection such as diabetes mellitus, a ureteral stent, or a urinary catheter.

The sonographic signs of suppurative pyelitis range from the features of an anechoic ob-

Pyonephrosis

An infected hydronephrosis leads to pyoneph- |

Pyonephrosis appears as a patchy heterogene- |

|

rosis. The sonographic findings are difficult to |

ous, tumor-like mass with a rounded or ellip- |

|

interpret because the familiar parenchymal si- |

tical shape. |

11.3 illustrate the typical |

nus echo pattern is absent and the normal renal |

The images in |

|

shape and structure are markedly changed, |

sonographic features of pyelitis, pyonephrosis, |

|

which can easily lead to misinterpretation. |

and renal pelvic abscesses. |

|

b Radiograph: ureteropelvic junction obstruction?, probably due to an aberrant vessel.

struction or a dilated renal pelvis with internal echoes to circumscribed round, oval, or bandlike hypoechoic or anechoic masses. Inflammatory swelling (to > 2 mm) of the renal pelvic walls, which appear as smooth, thin, hypoechoic bands, is virtually pathognomonic of this condition ( 11.3, Fig.11.1).

11.3, Fig.11.1).

11.3 Suppurative Inflammations of the Renal Pelvis

11.3 Suppurative Inflammations of the Renal Pelvis

Suppurative pyelitis

11

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

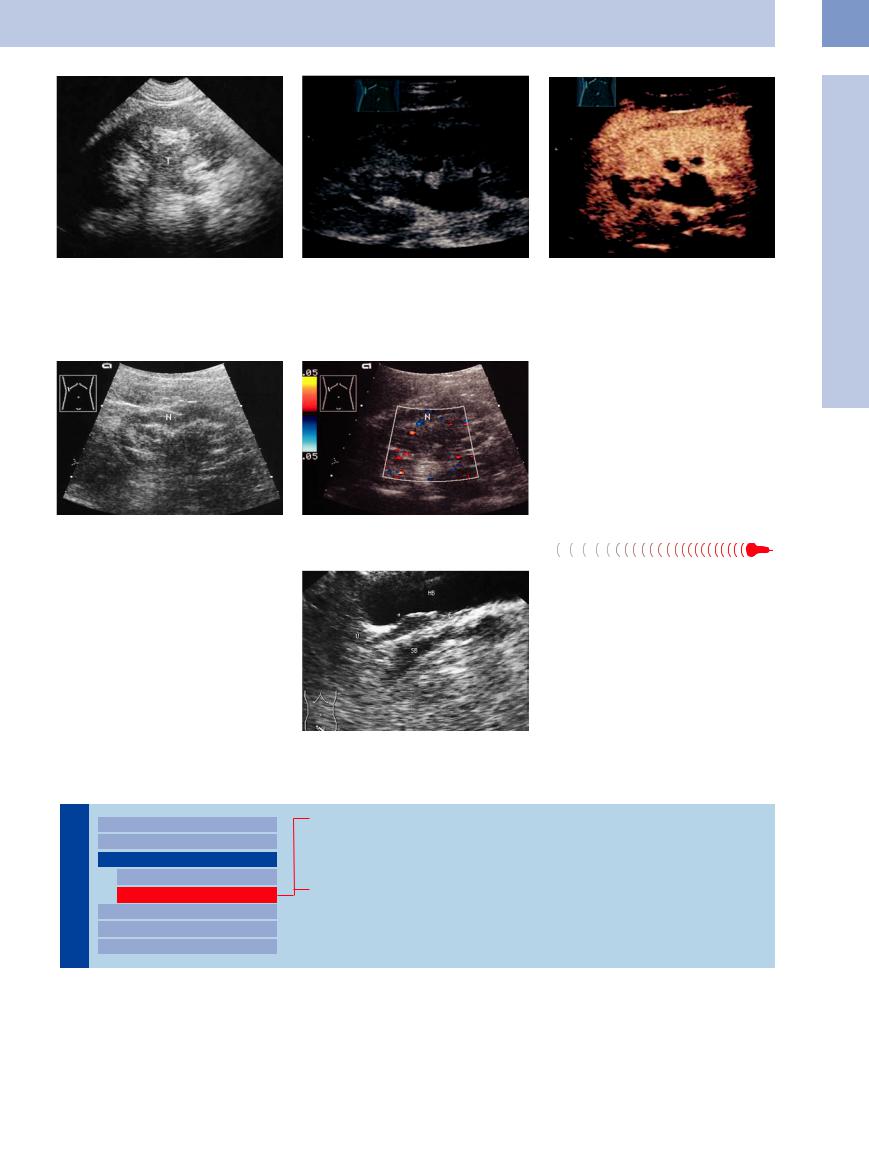

a Suppurative pyelitis. Slightly shifted scan plane shows a hypoechoic ureter with absence of central echoes (arrow). The hypoechoic “tram tracks” could represent the swollen ureteral wall. L = liver; N = kidney.

Renal pelvic abscesses

d Renal pelvic abscess (arrow) before treatment: elliptical hypoechoic mass.

b and c Bilateral suppurative pyelitis in a young diabetic man with septic temperatures.

b Right kidney: hypoechoic band-like mass in the renal pelvis/ureteropelvic junction (arrows). N = kidney.

e B-mode image: elliptical anechoic mass

(A) with a fine, hypoechoic pelvic wall that shows inflammatory swelling.

c Left kidney: hypoechoic separation of the central renal sinus echogenicity due to purulent fluid in the renal pelvis and calices (arrows).

f Pyelitis with abscess formation: two hypoechoic masses in the renal pelvis (A). N = kidney.

393

11

Urinary Tract

11.3 Suppurative Inflammations of the Renal Pelvis (Continued)

11.3 Suppurative Inflammations of the Renal Pelvis (Continued)

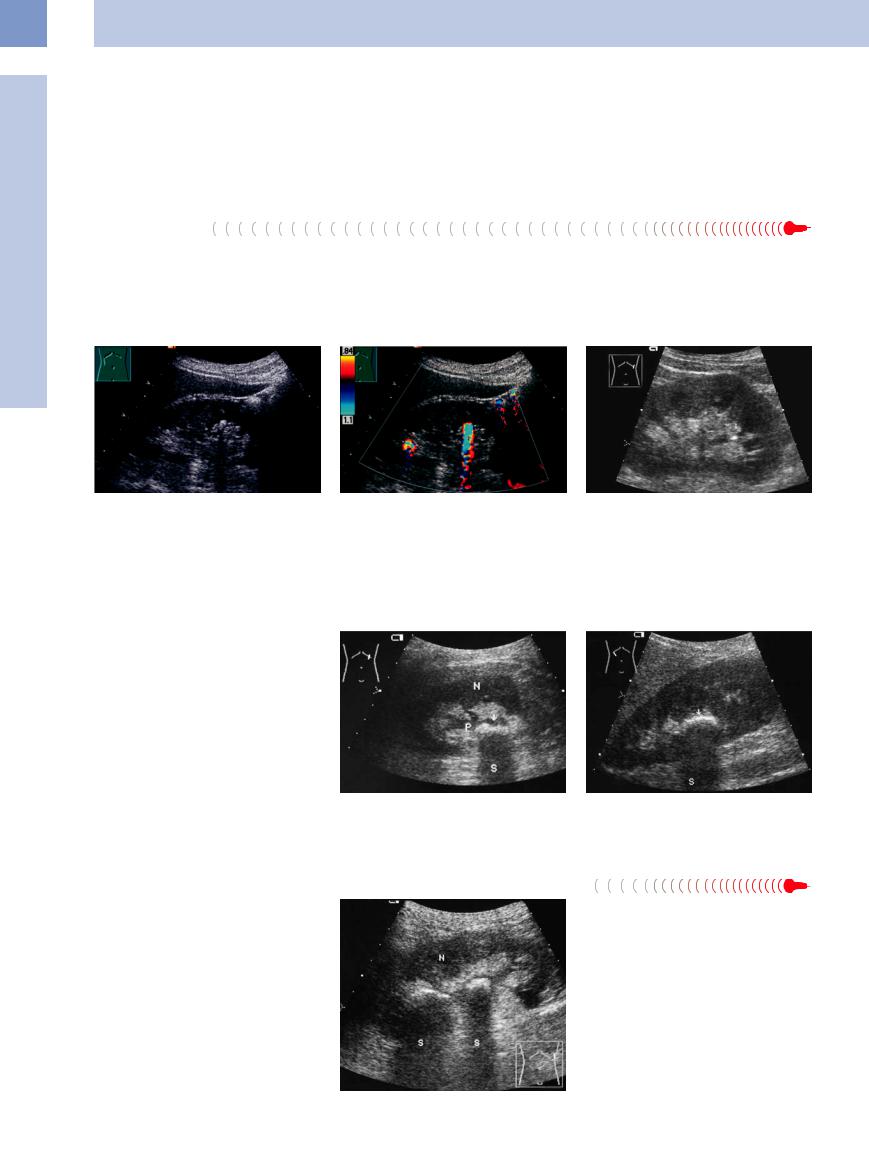

Pyonephrosis

g Pyonephrosis: extensive hypoechoic, |

h Pyonephrosis: hypoechoic abscesses |

i Pyonephrosis (surgery): left flank scan |

nonhomogeneous mass in the pyelocaly- |

with irregular margins (A) in suppurative |

demonstrates an irregular mass. The |

ceal system. |

pyelitis of the kidney (N). |

kidney can no longer be identified |

|

|

because the entire pyelocalyceal system |

|

|

has acquired a solid texture due to |

|

|

suppuration. |

■ Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass

Hypoechoic

Urinary Tract

Malformations

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass

Hypoechoic

Hyperechoic

Changes in Bladder Size or Shape Intracavitary Mass

Wall Changes

Urothelial Carcinoma

Ureteral Clots

The differential diagnosis of hypoechoic |

suppurative pyelitis, an infected obstruction, |

diagnosis is aided by color Doppler examina- |

changes in the renal sinus complex centers on |

renal cell carcinoma invading the renal pelvis, |

tion, which frequently shows internal vascular- |

the differentiation of urothelial carcinoma (see |

atypical renal parenchymal bands, parapelvic |

ity in tumors but not in abscesses, sinus lip- |

below) from other hypoechoic masses such as |

cysts, and sinus lipomatosis. The differential |

omatosis, or cysts (see 9.5). |

Urothelial Carcinoma

Classification. The majority of urinary tract tumors are urothelial carcinomas. They arise as malignant tumors from the transitional epithelium (urothelium) and therefore occur in the renal pelvis, ureter, and bladder. The following tumor types are named in the 2004 WHO classification of renal pelvic tumors:8

Urothelial tumors

●Infiltrating urothelial carcinoma

●Non-invasive urothelial neoplasias (carcinoma in situ, high grade, low grade)

–Non-invasive papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential

–Urothelial papilloma

Squamous neoplasms

Glandular neoplasms

●Adenocarcinoma

●Villous adenoma

Neuroendocrine tumors Melanocytic tumors Mesenchymal tumors

Hematopoietic and lymphoid tumors Miscellaneous tumors

Actual urothelial carcinomas—transitional cell carcinomas—are less common than renal cell carcinomas. They occur grossly in papillary or solid forms.

Ultrasound. The ultrasound appearance varies with tumor location. Tumors in the renal pelvis usually assume the shape of the pyelocaliceal system and may extend into the upper ureter as well as the renal parenchyma. They are somewhat more reflective than the renal parenchyma, but they may also be less echogenic.

A long-standing tumor may contain foci of liquefaction, giving it a cystic or abscess-like appearance.

A hemorrhagic cyst should be excluded, because a tumor may also be stemmed and mobile. Their high vascularization also helps in differentiating a tumor from sinus lipomatosis or an abscess.

The differential diagnosis includes metastases, and extension of renal cell carcinoma into the renal pelvis. Tuberculosis involves exclusively the ureter and is nonifiltrating (Figs. 11.34, 11.35, 11.36, 11.37;  11.2 d, see also Chapter 9, p. 354).

11.2 d, see also Chapter 9, p. 354).

Urothelial carcinoma in the ureter appears as a hypoechoic mass with associated obstruction to urine outflow ( 11.2 d).

11.2 d).

394

Fig. 11.34 Urothelial carcinoma (T) (surgery): hypoechoic |

Fig. 11.35 Urothelial carcinoma: hypoechoic mass in the |

Fig. 11.36 As in Fig. 11.35; CEUS demonstrates an en- |

mass in the pyelocaliceal system with extension into the |

renal pelvis of the right kidney (arrow). |

hancement within the supposed tumor mass (image |

ureter, indistinguishable from suppurative pyelitis or pyo- |

|

courtesy of Professor C. Goerg, University Hospital Gies- |

nephrosis in the B-mode image. (Color Doppler can help |

|

sen and Marburg, Marburg, Germany). |

by demonstrating intratumoral vascularity.) |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 11.37 Sinus lipomatosis, the main lesion requiring |

|

|

differentiation from urothelial carcinoma of the renal |

|

|

pelvis. |

|

|

a Gray-scale image: hypoechoic streaks in the sinus echo |

|

|

complex of the kidney (N). Sinus lipomatosis or urothelial |

|

|

carcinoma? |

|

|

b Color Doppler: absence of vascularity in the hypo- |

|

|

echoic mass is more consistent with sinus lipomatosis. |

Ureteral Clots

Ureteral clots appear as hypoechoic or heterogeneous tumor-like masses in the ureters with associated obstruction to urine outflow. They may occur in the setting of a generalized hemorrhagic diathesis, after surgical procedures, or in association with a renal tumor or urolithiasis. They are difficult or impossible to distinguish from primary tumors by ultrasound. The correct diagnosis is usually made from the history, the clinical course, or endoscopic inspection (Fig.11.38).

Fig. 11.38 Ureteral clot, caused by renal cell carcinoma bleeding into the ureter. Patient presented clinically with renal colic. Hypoechoic mass in the prevesical ureter (U). Arrows = echogenic ureteral ridge; HB = urinary bladder; SB = seminal vesicles.

Hyperechoic

Tract |

Malformations |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter |

||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass |

||

Urinary |

|||||

|

Hypoechoic |

||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Hyperechoic |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Changes in Bladder Size or Shape |

||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Intracavitary Mass |

||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Wall Changes |

||

|

|

|

|||

Caliceal Stones

Renal Pelvic Stone

Staghorn Calculus

Ureteral Stone

Urolithiasis. Urolithiasis can have many |

diseases with increased oxalic acid absorption, |

acidosis or a disturbance of cystine |

metabo- |

causes: primary or secondary hyperuricemia |

and inflammatory or neoplastic renal pelvic |

lism. Often, however, lithiasis results from the |

|

(tumor chemotherapy!), hypercalcemia, mal- |

diseases. Less frequent causes are congenital |

crystallization of salts dissolved in the urine, |

|

assimilation syndromes, inflammatory bowel |

or acquired metabolic disorders such as renal |

with no identifiable cause. Since |

crystals |

11

Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass

395

11

Urinary Tract

require a relatively static precipitation medium in order to grow, they tend to form at sites where a high salt concentration is combined with fluid stasis and a favorable pH. Stones therefore most commonly form in the renal pelvis and bladder.

Sonographic criteria. Regardless of the stone composition—urate or cystine/xanthine stones, calcium oxalate/calcium phosphate stones, or infection stones (struvite/carbonate apatite)

—ultrasound shows an intensely echogenic focus with distal acoustic shadowing. Because a stone surface echo is very difficult to discern within the high-level echoes of the renal sinus

Caliceal Stones

A renal caliceal stone is characterized by a stone echo with an acoustic shadow and by caliectasis, which occurs proximal to the site of the stone. Concomitant ectasia of the caliceal neck suggests a calculus located distal to the infundibulum, whereas a caliceal stone echo

not associated with caliectasis is difficult or impossible to distinguish from papillary calcification. The history and clinical presentation in these cases will suggest the correct diagnosis (Figs. 11.39, 11.40, 11.41).

complex, the presence of an acoustic shadow is important in confirming the diagnosis of urolithiasis. Not every echo represents a stone, even when associated with partial shadowing. It must also be consistently definable in multiple planes of section.

Fig. 11.39 Caliceal stones: caliectasis; supported caliceal calculus; incomplete shadowing.

Fig. 11.40 Same patient as in Fig. 11.39, CDS, high PRF: an intensive twinkling artifact in the region of the presumed calculus and an additional one in the upper pole. Confirmed kidney stones.

Fig. 11.41 Stone in a lower caliceal neck (arrow) with another, more distal outflow obstruction, causing very clear delineation of the caliceal stone in the fluid milieu of the pyelocaliceal system. (Without an acoustic shadow, ordinarily it would not be possible to distinguish the stone within the central echo complex.)

Renal Pelvic Stone

Renal pelvic stones, like caliceal stones, may be solitary or multiple. They have the same ultrasound appearance as caliceal stones but lack the typical isolated caliectasis that occurs with the latter. They may also be obstructive for one or more caliceal groups (Fig.11.42).

Fig. 11.42 Renal pelvic stone (arrow; acoustic shadow S). a Here a mild obstruction of the renal pelvis (P) delineates the stone in the left kidney (N).

Staghorn Calculus

Calculus

Because a staghorn calculus is associated with a broad linear echo or an irregular echogenic zone, it is easily missed when nonobstructive and may be mistaken for a bright central sinus echo. Depending on the scan plane, ultrasound may show a broad echo with a single broad associated shadow, or a scan in the caliceal plane may show multiple echogenic foci that cast separate shadows (Figs. 11.43, 11.44, 11.45, 11.46, 11.47).

b High-amplitude echo from a nonobstructive stone.

Fig. 11.43 Renal pelvic stone (partial staghorn calculus) with local obstruction of the middle and lower caliceal groups: broad hyperechoic zones with acoustic shadows

(S) in the midpelvic region of the left kidney (N).

396

Fig. 11.44 a and b Partial staghorn calculus.

a High-amplitude echo, shadowing, in the lower pole of the left kidney: supported nonobstructive stone.

Fig. 11.45 Staghorn calculus: multiple high-level stone echoes with acoustic shadows (S) throughout the pyelocaliceal system. Depending on the scan plane, ultrasound may demonstrate multiple isolated stone echoes as shown here or a broad linear echo (Fig. 11.46). N = kidney.

The differential diagnosis of hyperechoic masses in the renal sinus echo complex is reviewed in Table 11.2.

b CDS, high PRF: confirmed by the twinkling artifact.

Fig. 11.46 Staghorn calculus with massive caliectasis and a bright linear echo (arrows) with an acoustic shadow (SS). Massive, anechoic caliectasis with severe chronic renal congestion and parenchymal loss.

c Shadowing stone in the lower renal pelvis and a ureteral stone (U; acoustic shadows S).

Fig. 11.47 Radiographic view of a staghorn calculus (compare with Fig. 11.46).

Table 11.2 Differential diagnosis of echogenic masses in the sinus echo complex

●Kidney stone (Fig. 11.39)

●Vascular calcification (Fig. 9.87)

●Papillary calcification (Fig. 9.86)

●Nephrocalcinosis (Fig. 9.91)

●Tumor calcification

●Gas-forming abscess (Fig. 9.90)

●Medullary sponge kidney

●Inflammatory calcification (Fig. 9.93)

●Posttraumatic calcification

Ureteral Stone

The most frequent cause of renal colic is a |

vesical junction. Of these sites, the latter is the |

potential for contrast-induced diuresis with |

ureteral stone. Calculi tend to become im- |

most common. |

risk of fornix rupture and perirenal urinoma |

pacted at sites of physiological narrowing: the |

The landmark for locating the stone at ultra- |

formation (Fig.11.48). Figures 11.49, 11.50, |

ureteropelvic junction, the point where the |

sound is the dilated ureter. An intravenous uro- |

11.51, 11.52 illustrate some typical locations of |

ureter crosses the iliac vessels, and the uretero- |

gram can usually be omitted because of the |

ureteral stones. |

11

Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass

Fig. 11.48 Renal colic: urinoma; perirenal fluid collection (arrows), hardly dilated pelvis.

Fig. 11.49 Ureteral stone: diagnosis in renal colic with urinoma (see Fig. 11.48).

a The iliac stone is only detectable by the twinkling artifact. Additional stone in the prostatic urethra.

b Using this knowledge, the barely dilated ureter (U) and the stone become visible under magnification in the grayscale image (cursors; shadowing, S).

397