- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

9

Kidneys

■ Circumscribed Changes

Anechoic Structure

Kidneys |

Anomalies, Malformations |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Diffuse Changes |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Circumscribed Changes |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Anechoic Structure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hypoechoic or |

|

|

|

|

Isoechoic Structure |

|

|

|

|

Complex Structure |

|

|

|

|

Hyperechoic Structure |

|

|

|

|

Echogenic Structure |

Renal Cysts, Polycystic Kidney/Cystic Nephroma

Perirenal Cystic Masses

Lymph Cysts

Cystic Renal Cell Carcinoma, Intracystic Carcinoma

Papillary Necrosis, Cystic Degeneration of the Medullary Pyramids

Cavities

Abscess

Organized Hematoma

Urinoma, Seroma

Vascular Dilatations

Hydrocalices, Pyelectasis, Hydronephrosis

Cyst-like Metastases

Renal Cysts, Polycystic Kidney/Cystic Nephroma

Simple cysts (dysontogenic). Round, sharply circumscribed, anechoic masses located in or on the kidney and showing posterior acoustic enhancement can be confidently identified as primary (dysontogenic) cysts if, in addition to the usual cystic criteria, they show an absence of vascularity on color duplex scanning and there are no additional structural abnormalities in the affected kidney. Whether single or multiple, they represent tubular retention cysts that have resulted from dilatation of the Bowman capsule or proximal tubules. Consequently, they have a cyst wall that produces typical entrance and exit echoes in ultrasound but cannot always be directly visualized. Primary dysontogenic cysts display a typical location (Table 9.5;  9.2a–d).

9.2a–d).

Multiple cysts (dysontogenic). Kidneys that contain multiple cysts are usually of normal size. In contrast to a polycystic kidney, the renal cortex, medullary pyramids, and renal sinus are clearly defined. The multilocular cystic nephroma is to be considered as a special feature in earlyinfancy(age2 months–2 years).Itismostly unilateral and benign. It consists of irregular smallcystswithseptaeand showsno vascularity in CDS ( 9.2e, Fig. 9.72c,d, Fig. 9.9).9

9.2e, Fig. 9.72c,d, Fig. 9.9).9

Polycystic kidney disease (autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, ADPKD). This disease involves a polycystic malformation of the distal renal tubules, tubular epithelium, or tubular walls leading to a predominantly bilateral polycystic transformation of the kidneys. In ultrasound the kidneys are considerably enlarged and contain numerous cysts that completely alter the contours of the renal capsule and cause poor delineation of the renal borders. There is variable rarefaction of the parenchyma due to a combination of cyst compression, blooming effects, and interstitial fibrosis. Polycystic kidneys are commonly associated with cysts in the liver and other organs, and

Table 9.5 Classification of renal cysts by their location and structure (after Bosniak, earlier classification)

Location |

Type of cyst |

Renal cortex |

Renal cortical cyst |

Subcapsular |

Subcapsular cyst |

Peripelvic |

Peripelvic cortex cyst descending from the cortex |

Peripelvic |

Peripelvic lymph cyst with its origin from lymph vessels of the renal sinus |

Extrapelvic |

Peripelvic cyst spreading out of the renal pelvis |

Table 9.6 Classification of renal cysts21 (including CEUS)

Bosniak I |

Simple cyst, all cyst criteria present |

Malignant: |

|

|

~0% |

Bosniak II |

Minimally complex, a few thin (≤ 1 mm) septa |

Malignant: |

|

|

~0% |

Bosniak IIF |

Minimally complex but increased number of septa, minimally |

Malignant: |

|

thickened, minimal contrast enhancement within the septa. Cyst |

~25%22 |

|

> 3 cm diameter requiring follow-up or operation |

|

Bosniak III |

Complicated cyst (thick or multiple irregular septa > 1 mm), contrast |

Malignant: |

|

enhancement |

~54%22 |

Bosniak IV |

Clearly malignant, solid mass contrast enhancement with large |

Malignant: |

|

cystic or necrotic component |

~100% |

the initial ultrasound findings are unequivocal (Fig. 9.8; Fig. 9.17 d–f).

Atypical or secondary cysts. Atypical (complicated, Table 9.6) or secondary cysts differ from simple, uncomplicated cysts in their shape, location, or contents. They may be elliptical, polygonal, or oblong; they may show a parapelvic or extrarenal location; and they may contain internal echoes (thickened walls, septa, sedimentation, flakes, or clots) and blood vessels in

malignant tumors. These cysts need further diagnosis and should be followed up ( 9.2 g,

9.2 g,

Table 9.6).

Septated cysts. Renal cysts occasionally show fine septations that subdivide the cysts into separate compartments. Septated cysts require careful ultrasound scrutiny to differentiate them from cystic RCC. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) may be helpful in differentiating benign from malignant lesions; vascular-

344

9

Circumscribed Changes

Fig. 9.55

a Atypical (complicated) cyst with septae (arrow; Bosniak IIF).

b CEUS. There is no detectable blood flow (somewhat altered scan direction); follow-up of 3 years.

c Complicated cyst (Bosniak III), CEUS and operation: cystic carcinoma. Atypical subcostal oblique scan left upper abdomen (image courtesy of Professor C. Goerg, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Marburg, Germany).

Fig. 9.56 Hydatid cysts.

a and b Suspected hydatid cyst of the kidney (young Asian female): septated round mass. Hyperechoic marginal wall, no interior vascularization (CDS).

ized septae are probably malignant ( 9.2a, Fig. 9.55). Lesions having this appearance require surveillance and possible surgery. The differential diagnosis should also include a hydatid cyst and, in young boys, multilocular cystic nephroma (benign cystic nephroma), which demonstrate in ultrasonography a complex renal mass with numerous anechoic cysts separated by echogenic septae.

9.2a, Fig. 9.55). Lesions having this appearance require surveillance and possible surgery. The differential diagnosis should also include a hydatid cyst and, in young boys, multilocular cystic nephroma (benign cystic nephroma), which demonstrate in ultrasonography a complex renal mass with numerous anechoic cysts separated by echogenic septae.

Retention cysts due to scarring. Secondary retention cysts develop in one-third to one-half of all patients with chronic interstitial nephritis requiring dialysis. These cysts result from scarring of the renal tubules. Many of the cysts are misshapen and rather small, and most are related to the cortex ( 9.2 g, Fig. 9.37).

9.2 g, Fig. 9.37).

Hydatid cyst. Both the dog tapeworm (Echinococcus granulosus), which forms a primary cyst containing internal daughter cysts, and the fox tapeworm (Echinococcus multilocularis), in

c Hydatid cyst of the left kidney: Large loculations separated by thick septae (image courtesy Dr. G. v. Klinggräff, Hamburg, Germany).

which the daughter cysts invade and destroy the host tissues from the primary cyst, can cause hydatid disease in humans. The most frequently infected organ is the liver but other sites may be affected, including the kidneys. Sonographically, the cysts are outlined by an echogenic wall. Daughter cysts produce a ro- sette-like pattern. Echinococcus multilocularis may also appear as a solid tumor mass. Hydatid cysts require differentiation from cysts with internal septations (Fig. 9.56; see also

Figs. 2.65, 2.66, 5.26).

Perirenal Cystic Masses

Cystic Masses

Cystic renal lesions also require differentiation |

cystic/liquid adrenal processes, and splenic or |

from other anechoic masses in neighboring or- |

pancreatic tail cysts or abscesses. In the case of |

gans and from adjacent cystic processes. Peri- |

adherent fluid-filled bowel loops, the correct |

renal cystic masses may represent adherent |

diagnosis is supplied by using real-time ultra- |

bowel loops, the gallbladder, loculated ascites, |

sound to observe the moving bowel contents. |

Equivocal findings require further investigation, such as ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) ( 9.2h,i).

9.2h,i).

345

9

Kidneys

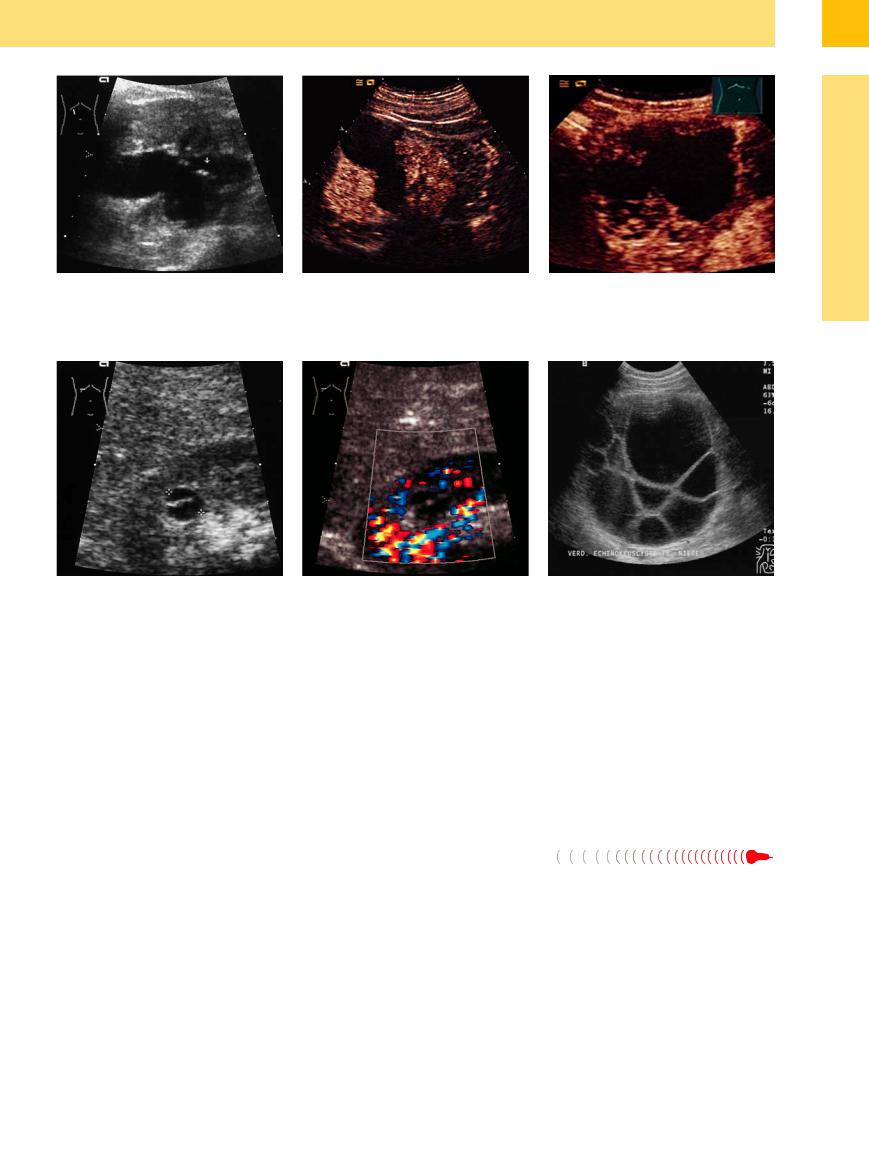

9.2 Renal Cysts and Perirenal Cystic Masses

9.2 Renal Cysts and Perirenal Cystic Masses

Perirenal cysts

a Septated right upper-pole cyst: slightly |

b Two subcapsular cysts (Z, z) appear as |

c Perirenal cyst, no vascularization. Left |

irregular cystic mass (Z) subdivided by an |

anechoic masses “piggybacked” on the |

lower pole cyst (C). |

echogenic septum (arrows). Di erential |

left kidney (N). |

|

diagnosis: cystic renal cell carcinoma. L = |

|

|

liver; N = kidney. |

|

|

Cortical and parapelvic cysts

d Peripelvic cyst (Z): round, anechoic mass |

e Multiple renal cysts: some of the cysts |

f Renal cortical cyst displaying all criteria: |

located in the renal sinus; apparently a |

(Z, z) are round; others are triangular or |

anechoic mass with smooth margins, a |

cortical cyst protruding into the renal |

bandlike. |

capsule (bright entry echo at the cyst |

sinus. L = liver; N = kidney. |

|

apex), and distal acoustic enhancement; |

|

|

dysontogenic tubular retention cyst. L = |

|

|

liver; N = kidney. |

Differential diagnosis of cystic masses

g Secondary cysts (arrows) in an atrophic |

h and i Di erential diagnosis of a perirenal |

i “Cyst-like” metastasis (Z) from a high- |

kidney with a hyperechoic rim of residual |

cystic mass. |

grade adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

parenchyma. The patient presented clin- |

h Large echo-free mass (cyst, Z) in the |

(see also Fig. 9.79). The indentation of |

ically with a plasmacytoma. |

triangle between the kidney, spleen, and |

the posterior hepatic surface suggests a |

|

pancreatic tail. Di erential diagnosis: cyst |

solid mass. L = liver. |

|

of the kidney, spleen, or pancreatic tail. |

|

Lymph Cysts

Parapelvic (peripelvic) lymph cysts. Parapelvic cysts generally represent lymph cysts, which have an epithelial lining. Projecting into the renal sinus, they present as flattened, usually elliptical cystic lesions. Generally these cysts are multiple.

When they are bilateral and show a fingerlike arrangement extending toward the renal hilum, they are classified as multiple parapelvic cysts or benign cystic lymphangioma. Between the elliptical, anechoic lesions tapering toward the hilum are hyperechoic, septum-like parti-

tions formed by the compressed sinus tissue and pyelocaliceal system ( 9.3a–h).10 Differentiation is required from renal pelvic dilatation due to a lower urinary tract obstruction, but the absence of ureteropelvic junction dilatation serves to exclude that condition. Occasionally there is no alternative to excretory urography for establishing a diagnosis. In the case of lymph cysts, the urogram will show sharply circumscribed impressions on the pyelocaliceal system (

9.3a–h).10 Differentiation is required from renal pelvic dilatation due to a lower urinary tract obstruction, but the absence of ureteropelvic junction dilatation serves to exclude that condition. Occasionally there is no alternative to excretory urography for establishing a diagnosis. In the case of lymph cysts, the urogram will show sharply circumscribed impressions on the pyelocaliceal system ( 9.3 d).

9.3 d).

Intrarenal or perirenal lymphoceles. Intrarenal or perirenal cystic lesions may also be lymphoceles, depending on the cause of the disease. They occur after surgery, in rejection episodes after renal transplantation, and also in chronic progressive renal diseases such as renal failure requiring dialysis. When they present as a perirenal mass, lymphoceles have an anechoic, cystic appearance. They may also contain septations ( 9.3e,f).

9.3e,f).

346

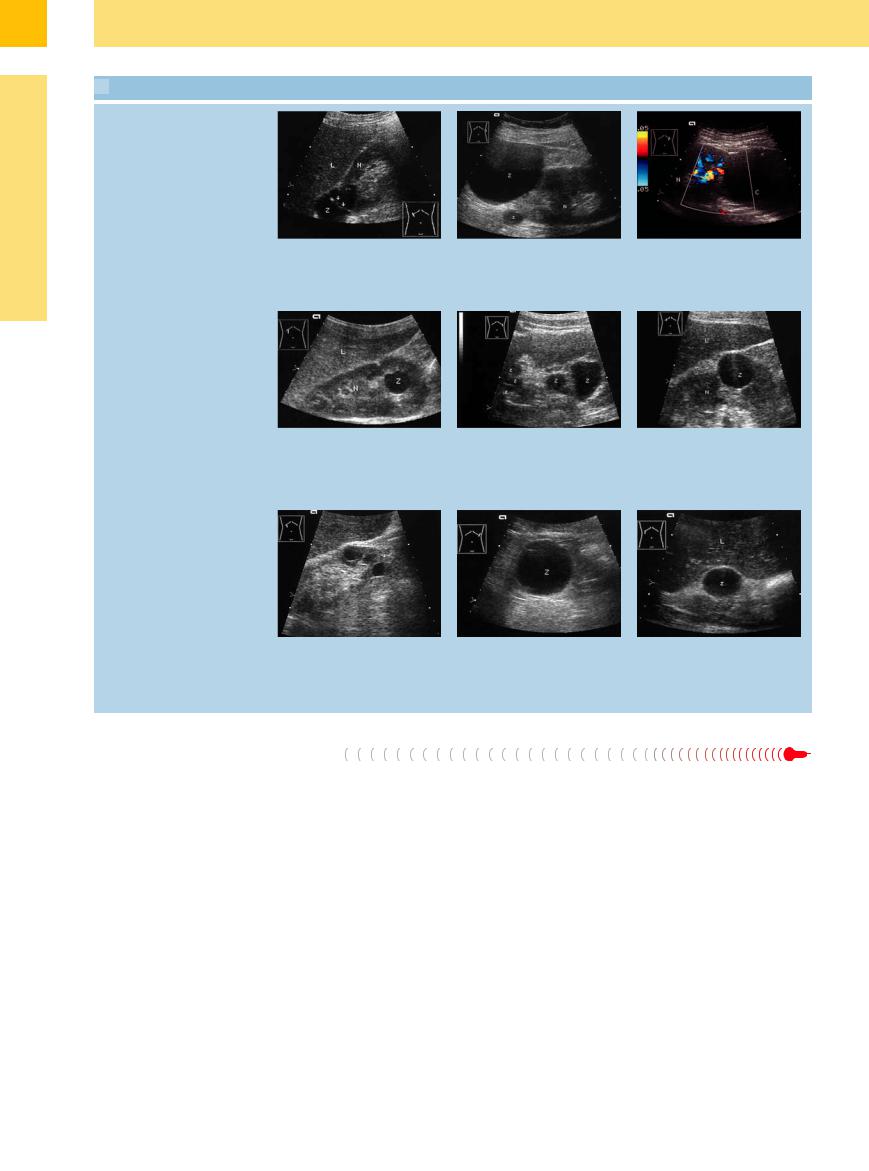

9.3 Lymph Cysts

9.3 Lymph Cysts

a and b Multiple parapelvic cysts on both sides: “benign cystic lymphangioma.”

a Right kidney (N): elliptical cysts radiating toward the hilum in a fan-shaped pattern. L = liver.

e Perirenal lymph cysts (arrows): small cysts, some showing a string-of-beads arrangement (varied at follow-ups). The patient presented clinically with severe right heart failure and erythrocytosis. N = kidney.

b Left kidney: a less obvious alignment toward the hilum.

f Postoperative lymphocele (C) following stone surgery with postoperative bleeding; very conspicuous medullary pyramids (arrows). Left nephrectomy. N = kidney.

c Parapelvic cysts, CDS: lack of interior vascularization, therefore no signs of tumor.10

g Parapelvine lymph cyst (Z) of the right kidney (N).

d Excretory urogram: multiple parapelvic cysts producing curved and smoothly margined impressions of the pyelocalyceal system.

h Parapelvic cyst (z) protruding from the right kidney (N; “extrapelvic cyst”).

Cystic Renal Cell Carcinoma, Intracystic Carcinoma

Carcinoma, Intracystic Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma. Cystic RCC is a rare form of renal carcinoma which can be inferred when more than 50% of the lesion is cystic (clear-cell carcinoma) (see Table 9.6). It shows a predominantly anechoic, cystic structure with more or less pronounced solid components. Foci of necrobiotic tumor liquefaction are common, especially in tumors of long duration.

CEUS allows the characterization of renal cystic lesions as benign or malignant at least as accurately as contrast-enhanced CT. It is more sensitive than CT in detecting enhancement of the cystic wall, septa, and solid components11 (Fig. 9.57, Fig. 9.78).

Intracystic carcinoma. Another type of cystic renal tumor is renal carcinoma that arises inside a cyst. Because intracystic carcinoma is extremely rare, it does not justify regular sonographic or CT follow-ups in patients with known cysts (Fig. 9.58).

9

Circumscribed Changes

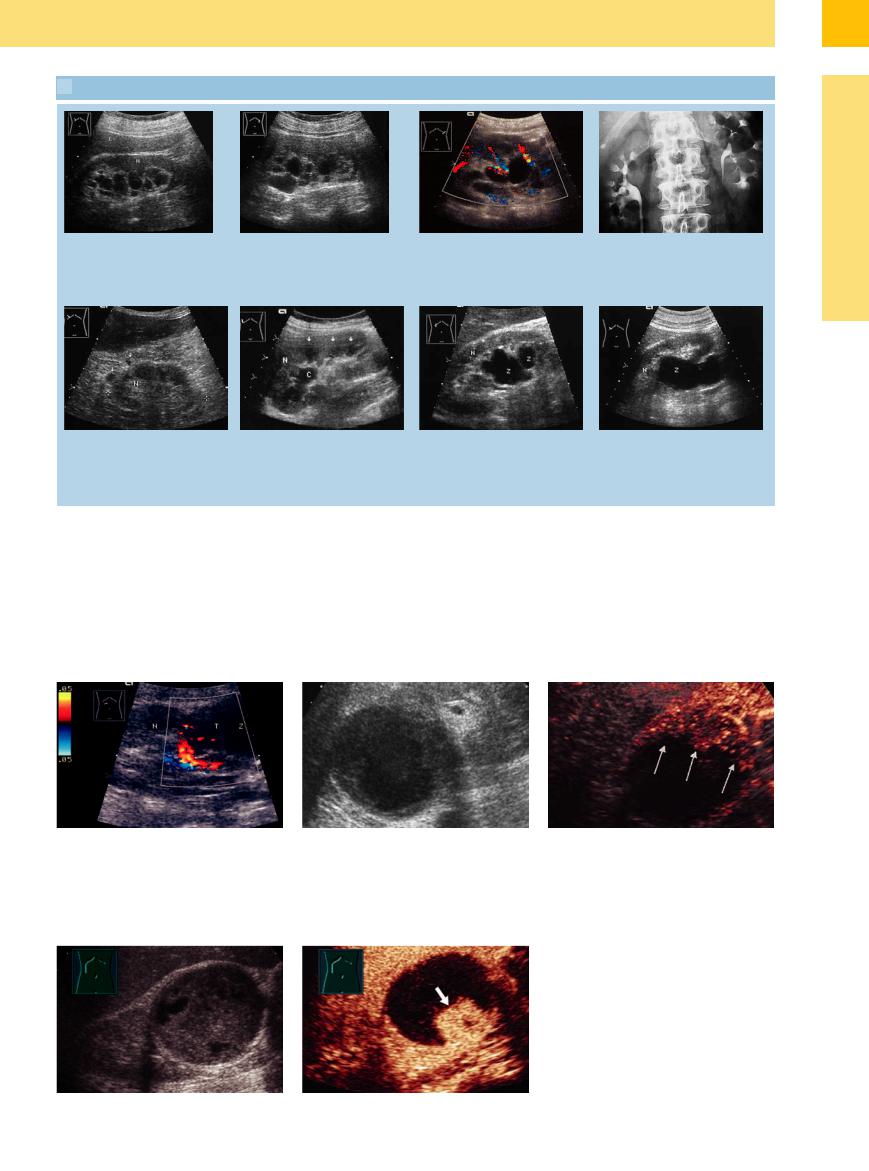

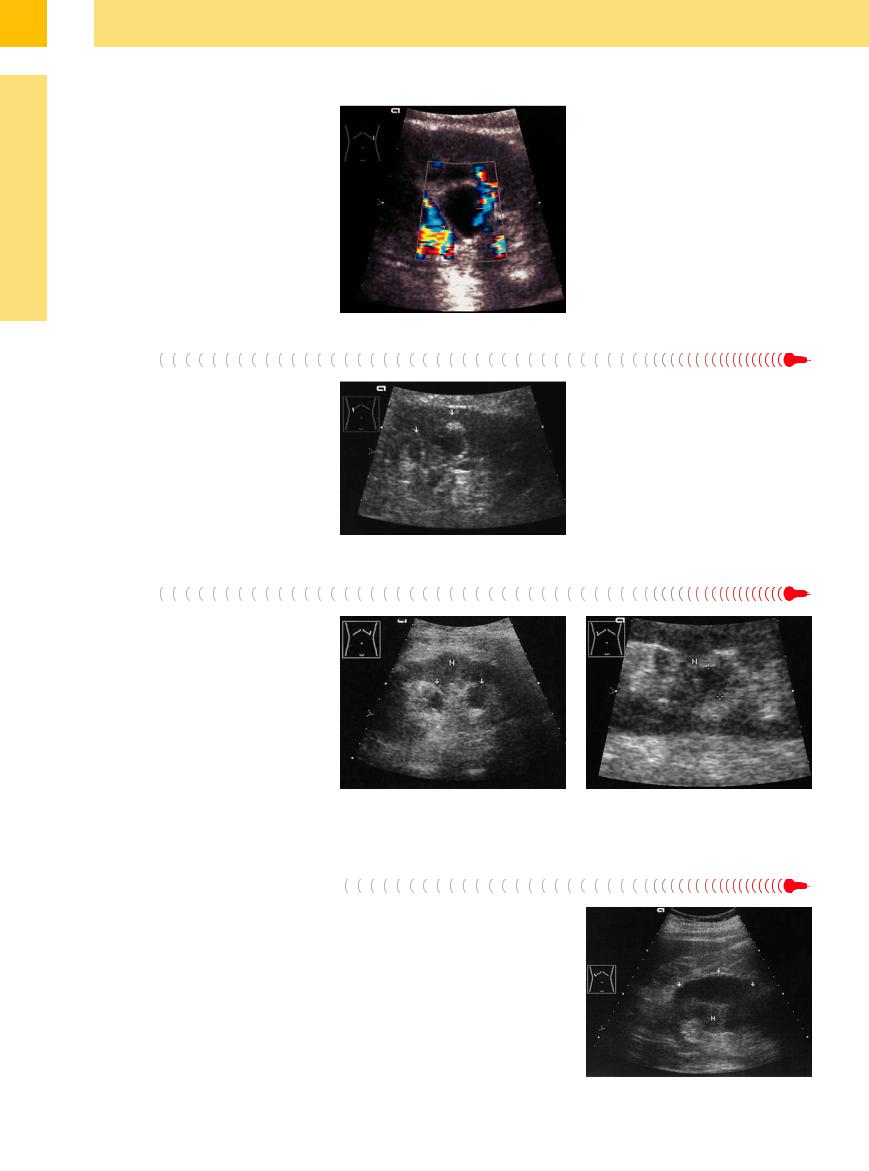

Fig. 9.57 Cystic renal cell carcinoma. No histology because of earlier nephrectomy on the left side.

a Transverse scan through the right upper abdomen: solid and cystic tumor components with pathological intratumoral vessels (cf. Fig. 11.7, p. 383). N = kidney. b and c Known renal cyst (2 years) (images courtesy of Professor C. Goerg, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Marburg, Germany).

b Smoothly margined cyst at the cranial pole of the kidney with thickened wall.

c CEUS: Enhancing at the cyst wall (arrows; Bosniak IV): renal cell carcinoma (RCC). N = kidney.

Fig. 9.58

a Large, smoothly margined, complex structured renal mass, probably intracystic hemorrhage (image courtesy of Professor C. Goerg, Department of Hematology–On- cology, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Marburg, Germany).

b CEUS: enhancement (arrow) on the bottom of the mass, the remaining part of the mass demonstrates no enhancement: Cystic renal cell carcinoma (Bosniak IV) (image courtesy of Professor C. Goerg, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Marburg, Germany).

347

9

Kidneys

Papillary Necrosis, Cystic

Necrosis, Cystic  Degeneration of

Degeneration of the Medullary Pyramids

the Medullary Pyramids

Papillary necrosis and caliceal cysts most commonly develop in a setting of purulent or nonpurulent interstitial chronic nephritis. They present as small cystic lesions projecting toward the calices.

In advanced diabetic nephropathy, it is not uncommon to find cystic degeneration of the medullary pyramids, which exhibit classic cystic features. Often they are located next to very hypoechoic medullary pyramids that may eventually undergo complete cystic transformation. The medullary pyramids disappear in the dialysis stage, often to be replaced by multiple small, secondary cysts that were once pyramids (Fig. 9.59,  9.1 d).

9.1 d).

Fig. 9.59 Cystic mass in the area of a medullary pyramid. Color Doppler shows no vascularity. Diabetes mellitus. Probably the cystic transformation of a medullary pyramid. N = kidney.

Cavities

Hematogenous spread of renal tuberculosis gives rise to cortical tubercles that descend into the tubules, papillae, and associated calices where they form ulcer cavities.

These cavities have a cystic appearance in ultrasound. While a purely cavernous-cystic process cannot be recognized sonographically as a tuberculous cavity, the late stage is additionally marked by the formation of scars and calcifications. This combination allows for a presumptive sonographic diagnosis (Figs. 9.60, 9.93, 9.94).

Fig. 9.60 Old cavernous (?) medullary pyramids that have undergone secondary cystic transformation (arrows). Ultrasound shows irregular, echo-free masses with a hyperechoic rim projected at the site of the medullary pyramids (see also Fig. 9.93). Patient had a known history of spinal tuberculosis.

Abscess

Renal abscess generally appears as a predominantly hypoechoic mass with internal echoes that distinguish it from a cystic lesion. Some abscesses, however, may be so hypoechoic that they mimic cystic lesions. A color void is seen on color Doppler scanning; CEUS depicts renal abscesses as nonenhancing regions and can be used to monitor their course (Fig. 9.61,  9.5 d,

9.5 d,

11.3 g,h).2

11.3 g,h).2

Fig. 9.61 Bilateral abscesses in a patient with septic uri- |

b Right kidney in magnified view: cystic mass with irreg- |

nary tract infection and diabetes mellitus. N = kidney. |

ular margins (cursors) in the renal sinus echo complex. |

a Left kidney: predominantly echo-free cystic abscesses |

|

with irregular margins (arrows). |

|

Organized Hematoma

Whereas fresh hematomas appear as echogenic, heterogeneous masses in ultrasound (see below), older hematomas appear increasingly hypoechoic to anechoic. Besides circumscribed parenchymal destruction, hematomas usually produce a subcapsular mass caused by the subcapsular extravasation of blood. This mass presents sonographically as perirenal fluid (Fig. 9.62). Color Doppler shows decreased perfusion in areas of renal contusion, while it shows an absence of perfusion in a hematoma.

The history and clinical presentation give additional information on the cause of these cystic lesions. Equivocal cases should be evaluated by CT, which is superior to ultrasound for this type of examination.

Fig. 9.62 Perirenal, elliptical echo-free mass (arrows): urinoma, hematoma following renal trauma. N = kidney.

348

9

Circumscribed Changes

scanning and spectral analysis. Arterial signals are typically recorded from aneurysms, while arteriovenous malformations exhibit high flow velocities (up to 180 cm/s) and low RI (0.32–0.25) (see Fig. 9.18).12 Renal artery aneurysms located outside the kidney are relatively easy to identify.

Renal vein ectasia or congestion. An ectatic or congested renal vein has the same sonographic appearance as an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation; therefore, color Doppler examination is diagnostically decisive. The vein can be confidently distinguished from an arterial aneurysm by spectral analysis (Fig. 9.63).

Fig. 9.63 Ectatic branches of the renal vein. L = liver; N = |

b Color Doppler: vascularity consistent with ectatic renal |

kidney. |

veins. |

a B-mode image: irregular cyst-like areas in the sinus |

|

echo complex. |

|

Hydrocalices, Pyelectasis, Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis

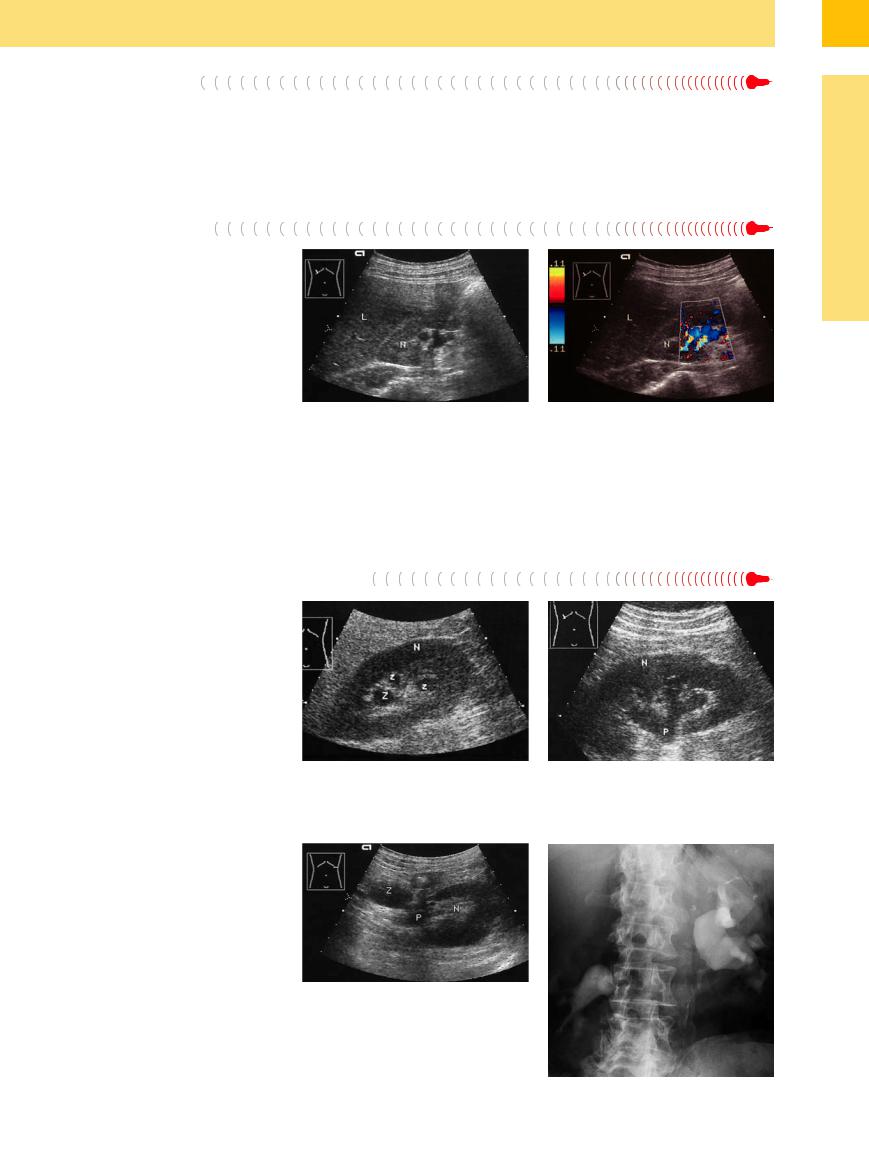

Certain sectional planes through distended calices in obstructive pyelocaliceal dilatation can create the impression of multiple renal cysts. In this case an oblique longitudinal scan, preferably from the posterior (ureter) side, will demonstrate the cystic enlargement of the calices.

Hydrocalices and hydronephrosis are seen in association with ureteral obstructions. Hydrocalices may also be congenital or secondary to caliceal stones or nephrocalcinosis (Fig. 9.64,

Fig. 9.65; see also Fig.11.10).

Fig. 9.65 Cyst combined with obstructive caliceal and pelvic ectasia. N = kidney.

a Transverse ultrasound scan through the left kidney: cyst (Z), pyelectasis (P).

b Excretory urogram: curved medial and lateral indentations in the upper portions of the calices. Renal pelvic indentation and congestion due to subpelvic obstruction (by a tumor?).

Fig. 9.64 Obstructive caliectasis. N = kidney.

a Scan through the calices, which resemble cysts (Z) in this plane.

b Oblique scan demonstrates the dilated pyelocaliceal system (P).

349