- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

Hypertrophy

The musculature of the intestinal wall up- |

(muscularis propria) despite the dilated lumen. |

Functional disorders such as irritable bowel |

|

stream of a stenosis or a functionally stenosed |

Typical such examples are the wall of the de- |

syndrome can be visualized by the extensive |

|

bowel segment will become hypertrophic be- |

scending colon and sigmoid in stenotic sigmoid |

accentuated layering of the entire colon wall, |

|

cause of increased activity |

and will display |

diverticulitis and the prestenotic bowel seg- |

accentuated haustra, and localized pain caused |

widening of the outermost |

hypoechoic layer |

ments in Crohn disease. |

by pressure throughout the entire colon. |

Tumor

Extended tumor growth may mimic diffuse |

typical characteristics of a focal tumor lesion. |

changes in the wall of the bowel and has to |

The musculature of the intestinal wall up- |

be differentiated especially from Crohn disease |

stream of a stenosis or a functionally stenosed |

as well as ischemia; however, these present the |

bowel segment will become hypertrophic as a |

Lymphoma

Lymphoma may lead to extended diffuse involvement of the bowel wall.

result of increased activity and will display widening of the outermost hypoechoic layer (muscularis propria) despite the dilated lumen.

Dilated Lumen

Tract |

|

|

|

|

Stomach |

|

Physiological Dilatation |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

Small/Large Intestine |

|

Prepping for the Study |

||

|

|

|

||||||

Gastrointestinal |

|

|

Focal Wall Changes |

|

Inflammation |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

Extended Wall Changes |

|

Ileus |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dilated Lumen |

|

Coprostasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Narrowed Lumen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tumor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foreign Body |

Small intestine. Under physiological conditions no chyme can be demonstrated in the small intestine (hence its name “intestinum jejunum,” meaning empty intestine). Oral intake of food and fluid will result, after some delay (temporary retention of the ingesta in the stomach), in a dilated lumen of the small bowel. Demonstration of fluid within the in-

testinal lumen in the fasting patient has to be regarded as pathological; further differentiation should include the size of the lumen, peristaltic activity, and the wall changes.

Large intestine. Because of its storage function, the large bowel is always full of scybala and air and therefore the sonographic assessment of

Physiological Dilatation

Fluid can be demonstrated in the small intes- |

small bowel display a normal wall texture. In |

tine within just a few minutes after oral intake; |

those jejunal segments filled with fluid, the |

the lumen becomes fluid-filled in segmental |

circular folds will be visualized as fine corruga- |

fashion, waves of contraction alternating with |

tions, while at the ileum the intraluminal sur- |

distension of the intestinal loops and propel- |

face will be smooth. Even a distended lumen |

ling the column of ingesta forward. The loops of |

will not have a diameter exceeding 15–20 mm, |

Prepping for

for the

the Study

Study

Specific loading by oral fluid uptake for sono- |

ment of changes in the lumen and of focal |

graphic bowel studies or rectal enemas for hy- |

and extended changes in the intestinal wall, |

drocolonic sonography (HCS) permit assess- |

detection and localization of circumscribed ob- |

its diameter is irrelevant. In pathological conditions or when particular types of bowel preparation are employed, fluid or sonolucent chyme can be visualized in the lumen, in which case the diameter of the lumen, particularly any change in lumen diameter, can be assessed during the sonographic study.

and during contraction the bowel will be wrung dry; here, the loops of the small bowel will evidence a thick muscular layer. The fine film of fluid remaining permits excellent delineation of the mucosa as well.

structions and stenosis, and especially assessment of the peristalsis.

7

Small/Large Intestine

287

7

Gastrointestinal Tract

Inflammation

In a fasting patient suffering from enteritis, the |

nal wall to a varying extent, accompanied by |

change their location. Other findings in enter- |

intestinal lumen will exhibit some fluid, but |

vigorous or even swirling hyperperistalsis |

itis may be the signs of peritonism (free intra- |

here the dilatation is less than after oral intake |

characterized by constant alternation between |

abdominal fluid) as well as regional lympha- |

and the luminal diameter rarely exceeds |

contraction and dilation without any rest in |

denopathy. |

10 mm (Figs. 7.55, 7.56, 7.57, 7.58). The primary |

these phases. During their peristaltic move- |

|

aspect is edematous thickening of the intesti- |

ments the loops of the small bowel constantly |

|

Ileus

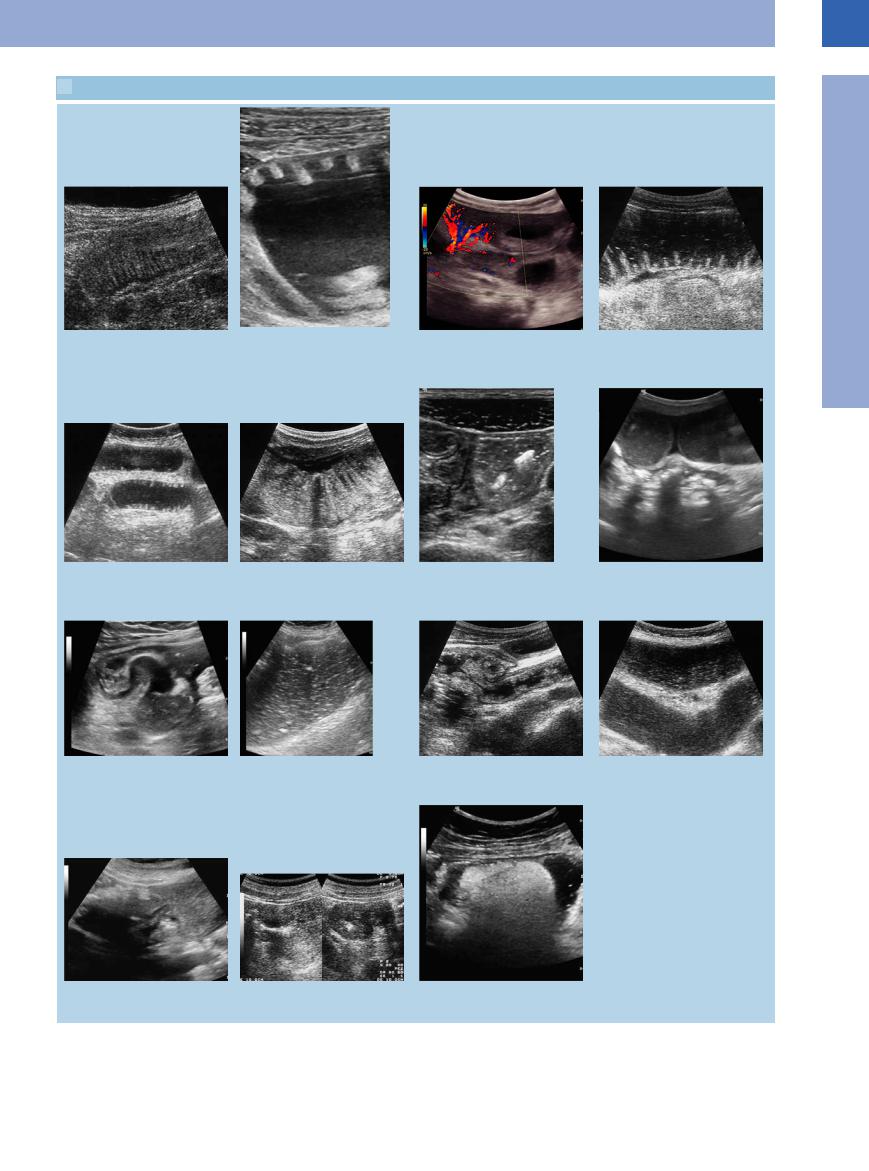

The leading sonographic sign of ileus is distension of the bowel. In the small intestine this dilatation of the lumen may be several centimeters. The lumen is filled with fluid (in the small bowel) or echogenic chyme (in the large bowel and in chronic ileus). Because of the constant filling of the lumen, the intestinal wall can be assessed quite well at the intraluminal surface. The circular folds in the small bowel appear rigid, giving rise to the so-called “piano key phenomenon,” and in the large intestine the haustra are easily identifiable. Despite the dilatation, with increasing duration and severity of the damage the intestinal wall itself may appear thickened and full of edema ( 7.4).

7.4).

Peristalsis. The most important sonographic criterion in the differential diagnosis of ileus is assessment of the peristaltic movement. The

The Various Types of Ileus

Ultrasound may be able to diagnose ileus 6 hours before it shows up on regular radiographic films.

All types of ileus. All types of ileus are characterized by significant distension of the lumen, signs of wall thickening (edema, hypertrophy), and finally signs of peritonitis with demonstration of an increasing amount of free fluid between the bowel loops. The typical air–fluid interfaces have a sonographic counterpart: with the patient supine, the air-filled intestinal loops will block imaging with the probe on the anterior abdominal wall, while a study with the probe on the lateral abdominal wall will demonstrate quite well the intestinal loops distended by the fluid/chyme, and their peristalsis, thus permitting better differentiation of the ileus.

early stages of mechanical ileus demonstrate vigorous peristaltic activity of the wall, which, however, is ineffective and results only in incomplete contraction. The intraluminal column of fluid exhibits pendulating peristalsis, while during the later stages the unsuccessful peristalsis of the intestinal wall will cease completely. The intraluminal fluid will slosh gently back and forth and finally will simply stop moving. This stage of the mechanical ileus can no longer be differentiated from paralytic ileus, with the same rigidly distended lumen, thickened wall, and signs of peritonism (free fluid).

It is nowadays possible to distinguish the causes of mechanical ileus as well as paralytic ileus.

Table 7.6 summarizes the causes of mechanical ileus and Table 7.7 gives an overview of diagnoses accompanying a paralytic ileus that can be established sonographically.

Table 7.6 Sonographically visible causes of mechanical ileus

●Inflammatory stenosis (Crohn disease, diverticulitis)

●Adhesions, bridle

●Intussusception

●Hernia

●Volvulus and torsion

●Tumor

●Gallstone

●Foreign body

Table 7.7 Sonographically visible causes of a paralytic ileus

●Acute pancreatitis

●Acute appendicitis

●Acute cholecystitis

●Ureterolithiasis with colic

●Intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal abscess

●Retroperitoneal hematoma

●Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

●GI perforation

Mechanical ileus. Initially this will demonstrate hyperperistalsis in those intestinal segments upstream of the obstruction, which itself can quite often be visualized sonographically, but the chyme/fluid will no longer be propelled in a directed fashion. In addition to antegrade “squirting” movements, more and more retropulsion (backward sloshing) becomes evident as well as pendulating motion of the intraluminal fluid. During the late stages of mechanical ileus this hyperperistalsis will disappear completely, the intestinal wall will be seen to initiate some ineffective efforts of contraction, and the intraluminal column of fluid sloshes back and forth gently until it finally rests. In this phase movement of the intraluminal fluid is caused by movements from breathing and pulse activity. Downstream of the mechanical obstruction the bowel will be contracted, demonstrating a collapsed lumen and feeble, futile peristalsis or no obvious peristaltic activity at all (so-called starvation gut).

Paralytic ileus. This type of ileus is characterized by luminal distension, thickening of the wall, and the signs of peritonism (free fluid). The intestinal wall does not exhibit any peristaltic activity and the intraluminal column of fluid is static; this situation cannot be differentiated from advanced mechanical ileus, unless it is possible to visualize the cause underlying the mechanical obstruction.

Intestinal disruption of propulsion. The diagnosis of mechanical or paralytic ileus based on sonography should only be given if a cause can be determined by sonography. If typical signs of an ileus can be detected but the cause remains unknown, the term “intestinal disruption of propulsion” should be used.

288

7.4 Ileus

7.4 Ileus

a Enteritis with a small fluid film on the circular folds.

e Rigid circular folds displaying the piano key phenomenon.

i Conglomerate of small-bowel loops with an incarcerated bowel loop as a cause (or consequence) of ileus.

m Cause of a mechanical ileus: colonic tumor with filiform stenosis and inspissated content in the lumen of the gut.

b Ileus: distended small bowel loops with typical demonstration of the circular folds.

f Free fluid in peritonism and intramural gas in the jejunal wall.

j Ileus with distended bowel loop, inspissated content.

n Cause of a mechanical ileus: stenotic tumor of the right flexure, longitudinal and transverse scan.

c Chronic ileus with peritonitis (inflammatory hypervascularization) and rigid dilated and wall-thickened small-bowel loops.

g Mechanical ileus: demonstration of distended bowel loops and emptied contracted bowel loops (so-called “starvation gut”).

k Ileocecum in chronic ileus (stenotic tumor of the hepatic flexure).

o Submucous lipoma in the sigma with symptoms of ileus.

d So-called “piano key” phenomenon in mechanical ileus, in addition, free fluid signifying peritonism.

h Mechanical ileus: ventral distended flu- id-filled bowel loops, posterior emptied contracted bowel loops (starvation gut).

l Chronic ileus in incarcerated inguinal hernia (Fig. 7.53).

7

Small/Large Intestine

289

7

Gastrointestinal Tract

Coprostasis

The colon filled with gas or feces can be identified by its prominent arching haustra: a perfectly normal finding, but intensified in coprostasis. In irritable bowel syndrome, local tenderness may often be elicited along the course of the colon.

Tumor

A large polypoid tumor may fill the lumen completely (Fig. 7.67). It may be identified by indirect signs (e. g., as cause of mechanical ileus) or the visualization of tumor vessels in

the polypoid mass may facilitate the differentiation of tumor from feces. A possible complication is the tumor acting as the leading point in intussusception.

Foreign Body

It is exceptionally rare for foreign bodies to be identified and located as such; quite often, it is possible only if they are sufficiently large to produce complete obstruction with subsequent mechanical ileus.

Narrowed Lumen

Tract |

|

|

|

|

Stomach |

|

Tumor Stenosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

Small/Large Intestine |

|

“Starvation Gut” |

||

|

|

|

||||||

Gastrointestinal |

|

|

Focal Wall Changes |

|

Ischemia |

|||

|

|

Extended Wall Changes |

|

|||||

|

|

|

Atrophy |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dilated Lumen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Narrowed Lumen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The lumen may be narrowed by changes in the bowel wall (tumor, inflammation, invasion) or by external effects (adhesions, tumor, hernia).

Tumor Stenosis

Carcinomas that grow primarily in circular fashion, but also off-center, as well as lymphomas can narrow the lumen until there is a filiform stenosis, and finally a complete stoppage with the full-blown clinical picture of mechanical ileus (Figs. 7.66, 7.67, 7.68). Apart from the pathological gut signature of the tumor, ultrasonography can demonstrate the distended intestinal loops proximal to the obstruction, while downstream there is the poststenotic “starvation gut” (see below).

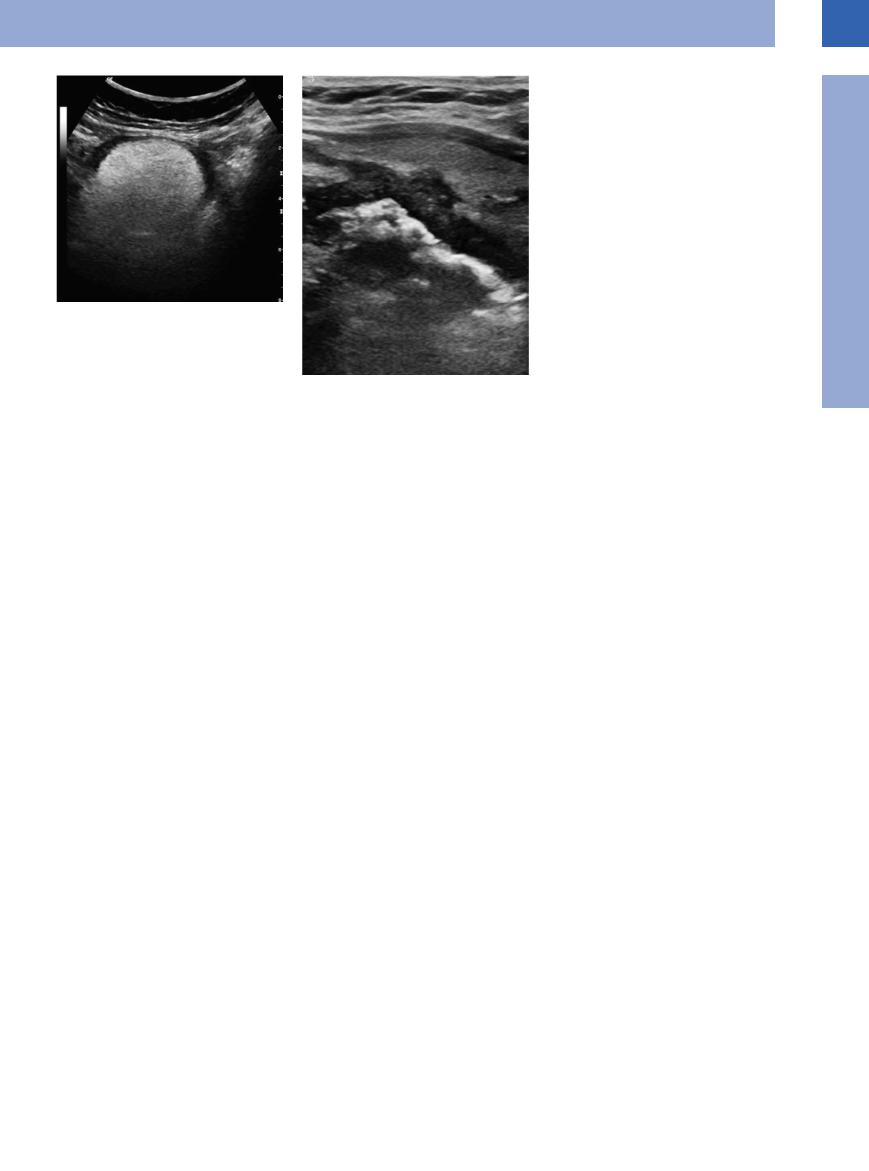

Fig. 7.66 Carcinoma of the transverse colon. Loss of the wall layering, eccentric externally growing tumor, stenotic lumen, posterior enlarged lymph nodes.

290

Fig. 7.67 Occlusion of the sigmoid colon caused by a large polypoid lipoma.

Fig. 7.68 Pathological gut signature: typical tumorous target sign (here, esophageal carcinoma) with loss of the normal wall layering; stenosis of the lumen; infiltration into the surrounding fatty tissue.

“Starvation  Gut”

Gut”

Compared with the distended intestinal loops proximal to the obstruction, in mechanical ileus the bowel segment distal to the obstruction will be contracted and empty.

Ischemia

In chronic ischemia there is extended hyperechoic thickening of the intestinal wall with a markedly narrowed lumen.

Atrophy

Bypassed intestinal loops demonstrate a constricted lumen.

7

Small/Large Intestine

291

7

Gastrointestinal Tract

Tips, tricks, and pitfalls

The GI tract can often be easily examined sonographically, but it can never be examined completely. The nihilists therefore line up against the enthusiasts.

The sonography of the intestine is mainly indicated and important (first-choice method) in emergencies, such as acute appendicitis, diverticulitis, ileus, perforation, and abscesses.

Furthermore, sonography provides important additional information on the extent, activity, complications, and differential diagnosis of chronic inflammatory bowel disease and has its merits in monitoring progress and the recognition of complications. Sonography can help guide a therapeutic intervention to puncture and drain abscesses.

The use of sonography helps differentiate between other chronic inflammatory bowel diseases and delivers important additional information (Fig. 7.69). It is a diagnostic instrument, and can be used to differentiate and monitor progression of ischemic bowel diseases.

The information value of sonography is limited, since the technique is dependent on visibility and

Fig. 7.69 High-resolution percutaneous ultrasound is better than its reputation suggests. The layers of the intestinal wall are visible, if the measured compression method is used. In the case at hand, a temporary invagination is visible during an infectious enteritis with lymphadenopathy.

References

[1]Schwerk WB, Beckh K, Raith M. A prospective evaluation of high-resolution sonography in the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1992;4:173–182

[2]Solvig J, Ekberg O, Lindgren S, Florén CH, Nilsson P. Ultrasound examination of the small bowel: comparison with enteroclysis in patients with Crohn disease. Abdom Imaging 1995;20(4):323–326

cannot be implemented in a standardized way. This is true especially in the detection and staging of tumors (tumor exclusion is not possible) so sonography cannot be used for screening of polyps and early carcinomas.

Sonography of the upper intestinal tract

(stomach sonography) is suitable only to localize a tumor and for the diagnosis of a gastric outlet obstruction.

Sonography is suitable for the diagnosis of a perforated ulcer, even if it is walled-off. It is not suitable for the diagnosis of unperforated ulcers or exact tumor staging.

In particular, the combined use of sonography and endoscopy by the same examiner is very valuable for the patient: it is the patient who benefits most, if the gastroenterologist “opens both eyes.” Endoscopy allows the endoluminal assessment of the mucous membrane and the possibility of a biopsy. Sonography make it possible to assess the surrounding, the wall and the movement (peristalsis) of the intestine.

If a circumscribed thickening of the wall is detected sonographically, endoscopy should follow.

Fig. 7.70 Endosonography is excellent for detecting the infiltration of mucosal or submucosal tumors into deeper layers of the GI wall. In the case at hand, a solely mucosal tumor has not reached the muscularis propria and can easily be removed endoscopically.

[3]Gasche C, Moser G, Turetschek K, Schober E, Moeschl P, Oberhuber G. Transabdominal bowel sonography for the detection of intestinal complications in Crohn’s disease. Gut 1999;44(1):112–117

[4]Neye H, Voderholzer W, Rickes S, Weber J, Wermke W, Lochs H. Evaluation of criteria for the activity of Crohn’s disease by power Doppler sonography. Dig Dis 2004;22(1): 67–72

In principle, we see more than we think or expect!

The GI tract examination can be time consuming and has to be practiced, meaning that points of reference have to be found—e. g., the sigmoid region, systematic tracking of the colon, or systematic search for the appendix by using the cecum and the iliac vessels as leads.

For an orientational view of the bowels a convex abdominal probe (3–5 MHz) should be used, followed by a high-frequency linear probe (5–10 MHz) for a systematic examination. The measured compression method should be applied, to eliminate or avoid air, intestinal contents, and other interference effects. Important additional information is obtained by sonopalpation and a targeted sonographic search for tender points. Especially in emergencies, sonography is the first method of choice. This applies to the detection of air in cases of perforation (see Chapter 8), but also in cases of sealed, encapsulated gas collection. The increased accumulation of liquid or obstructed passage (incomplete and complete ileus) can be detected significantly earlier than with conservative radiologic techniques (5–6 h). Tumor detection is easily possible, if the intestinal wall is clearly infiltrated (T2–3), but the sonographic method is inadequate if early stages of mucosal changes or of polyps need to be detected.

A sample may possibly be obtained by ultra- sound-guided percutaneous needle biopsy, if a visible tumor cannot be reached endoscopically. The stated complication rate is very low (< 0.1%). Endosonography (EUS) complements sonography and endoscopy in many cases and is applied in a target-oriented and sequential way. The method is established for tumor staging (infiltration depth, T-staging, esophagus, stomach, rectum), diagnostic of mucosal and submucosal tumors (e. g., GIST) (Fig. 7.70), for assessing operability (e. g., in bile duct and pancreatic tumors), and finally to differentiate tumors and for targeted ultrasound-guided FNA. EUS can be used to exclude very small concretions in the bile duct.

[5]Arienti V, Campieri M, Boriani L, et al. Management of severe ulcerative colitis with the help of high resolution ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91(10):2163–2169

292