- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

5

Spleen

in fanlike fashion respectively to and from the |

is a landmark structure in ultrasound studies |

(“ultrasound window”); this may be possible |

splenic hilum ( 5.1a,b). The arterial blood is |

for locating the tail of the pancreas ( 5.1f,g). |

even if the tail of the pancreas cannot be dem- |

supplied by the splenic artery ( 5.1c) and only |

Quite frequently it is possible to visualize the |

onstrated from anterior because of intestinal |

rarely via accessory arteries in the gastro- |

area of the pancreatic tail by insonation |

gas ( 5.1h,i). |

splenic ligament. The trunk of the splenic vein |

through the spleen from the patient’s left side |

|

■ Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

Spleen |

|

Large Spleen |

|

Malignant Invasion |

||

|

|

|

Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Diffuse Parenchymal Changes |

|

Benign Nonhomogeneity |

|

|

|

|

Small Spleen |

|

|

Focal Changes of the Spleen

Diffuse nonhomogeneity of the splenic texture |

sonographic follow-up, and possibly ultra- |

is rare, especially when compared with tex- |

sound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy.1 |

tural nonhomogeneity of the liver. Definite di- |

The sonographic appearance is character- |

agnosis is based on history, clinical picture, |

ized by a “subjectively” inhomogeneous |

|

splenic parenchyma without definite delinea- |

tion of individual focal masses (compared with healthy hepatic parenchyma, the tissue of the healthy spleen appears somewhat “more homogeneous”). However, the transition to focal micronodular splenic disorder is fluent.

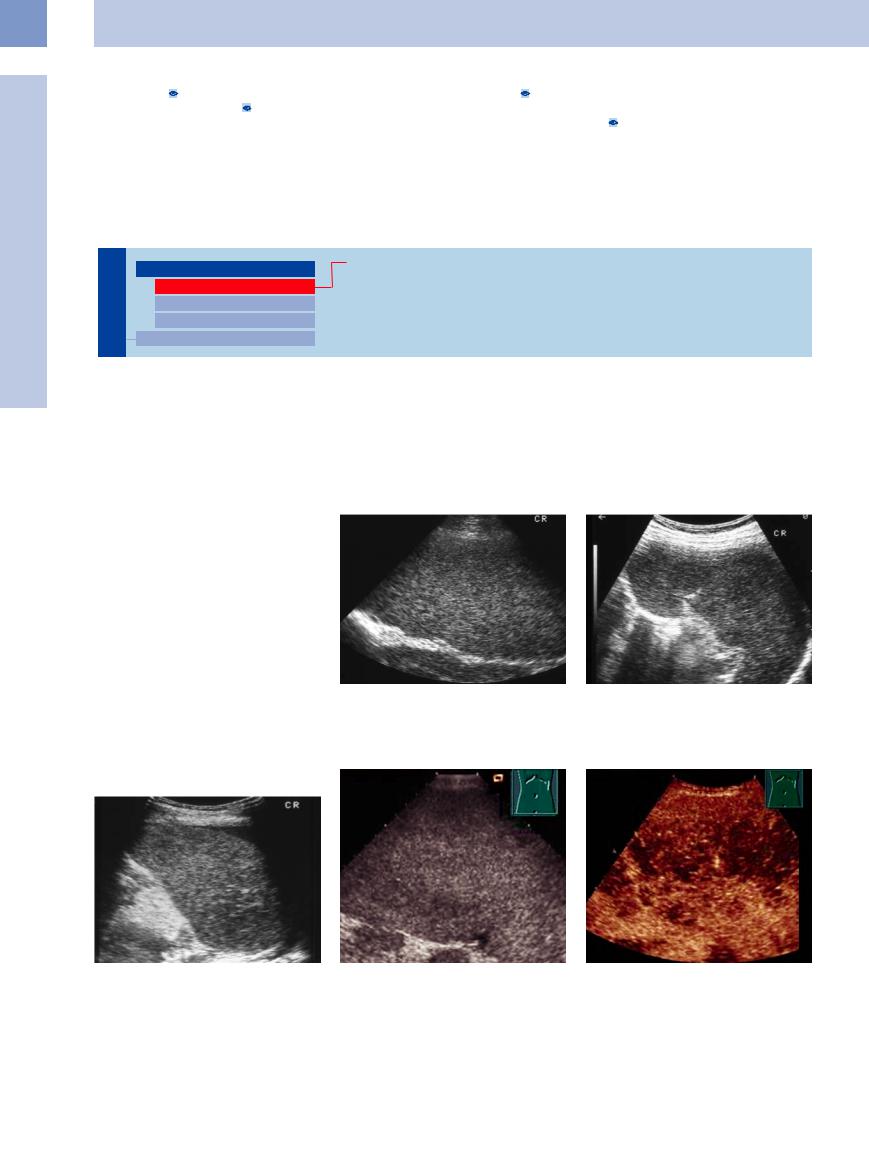

Malignant Invasion

Diffuse splenic change as a sign of malignant invasion is frequently found in low-grade lymphomas (Fig. 5.9), in Hodgkin lymphoma (Fig. 5.10), and rarely as diffuse splenic invasion by a solid tumor (Fig. 5.11a).

On occasion, in individual cases focal masses in the spleen with diffuse nonhomogeneity can be detected by contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS; Fig. 5.11b,c).1–4

Fig. 5.9 Splenomegaly with coarse splenic parenchyma in |

Fig. 5.10 Diffuse textural nonhomogeneity compatible |

malignant lymphoma. This finding is compatible with |

with splenic invasion in Hodgkin disease. |

splenic invasion. |

|

Fig. 5.11 |

b Diffuse structural inhomogeneity in a patient with |

c Hypoechoic lesions in the spleen are detectable by |

a Coarse splenic parenchyma in metastasizing breast |

malignant lymphoma. |

CEUS. |

cancer. This finding is suspicious for splenic metastasis. |

|

|

206

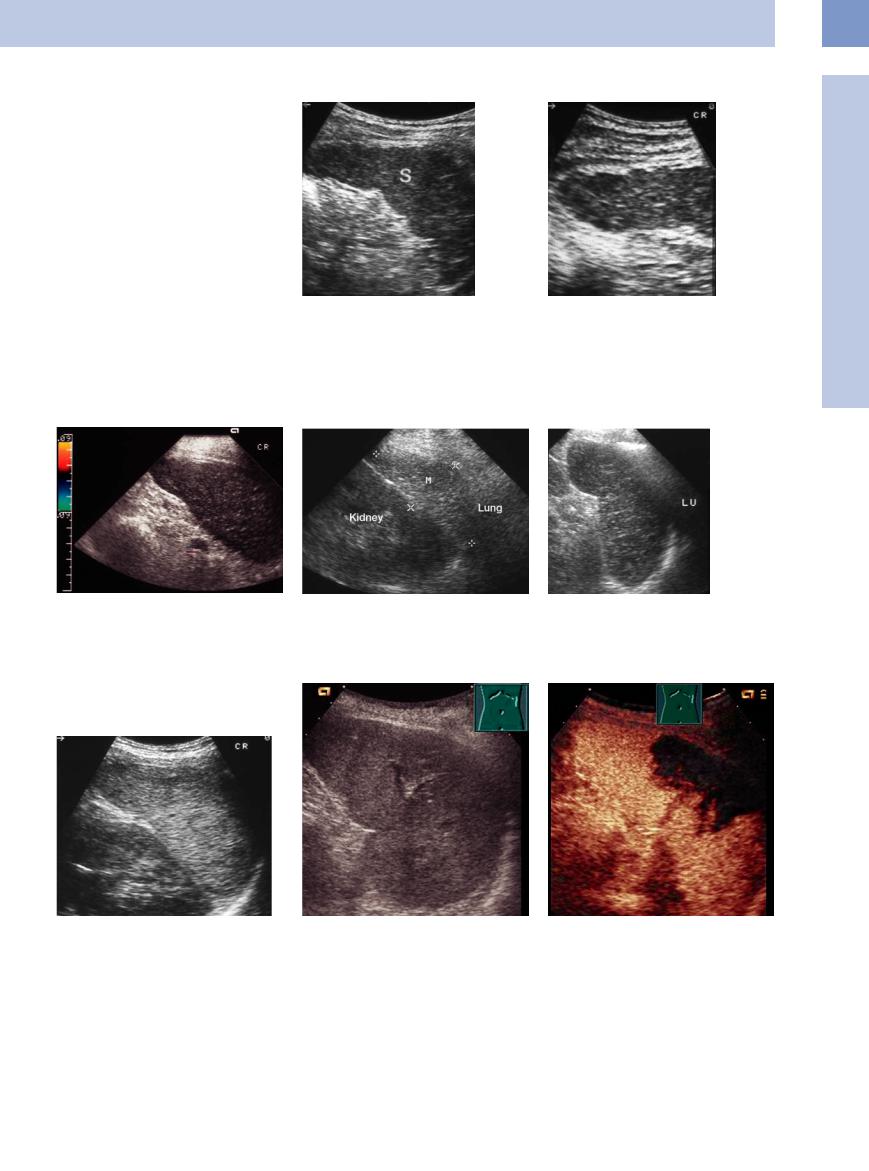

Benign Nonhomogeneity

Diffuse nonhomogeneity may be demonstrated in some cases of:

●Collagen disease (e. g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa)

● Benign granulomatous disease (Fig. 5.12) (e. g., tuberculosis, Wegener granulomatosis, sarcoidosis)

●Bacterial infection

●Amyloidosis (Fig. 5.13)

●Obstruction of the splenic artery

●Thorotrast exposure (Fig 5.14)

●Portal hypertension (Fig. 5.15)

●Incidental finding in “healthy” patients (Fig. 5.16a)

Vascular causes of diffuse nonhomogeneity of the spleen can be reliably detected by CEUS (Fig. 5.16b,c).

Fig. 5.12a and b Diffuse textural nonhomogeneity of the spleen (S) with undulating surface in Wegener disease. This finding is compatible with granulomatous invasion.

5

Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

Fig. 5.13 Coarse splenic parenchyma in amyloidosis. Color-flow Doppler scanning cannot demonstrate any flow signals. This finding is indicative of functional hyposplenism.

Fig. 5.16

a Textural nonhomogeneity of the spleen in a patient without obvious clinical pathological findings. The etiology remains uncertain.

Fig. 5.14 Small spleen with increased echogenicity in known Thorotrast exposure. M = spleen.

b Diffuse structural inhomogeneity in a patient with endocarditis.

Fig. 5.15 Coarse splenic parenchyma in long-term portal hypertension and hepatic cirrhosis. This finding is compatible with splenic fibrosis. LU = lung.

c Anechoic lesions corresponding to splenic infarctions are detectable by CEUS.

207

5

Spleen

Large Spleen

Spleen |

|

Large Spleen |

|||

|

|

|

|

Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diffuse Parenchymal Changes |

|

|

|

|

|

Small Spleen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Focal Changes of the Spleen |

|

|

|

|

|

||

Infection

Congestive Splenomegaly

Systemic Hematological Malignancy

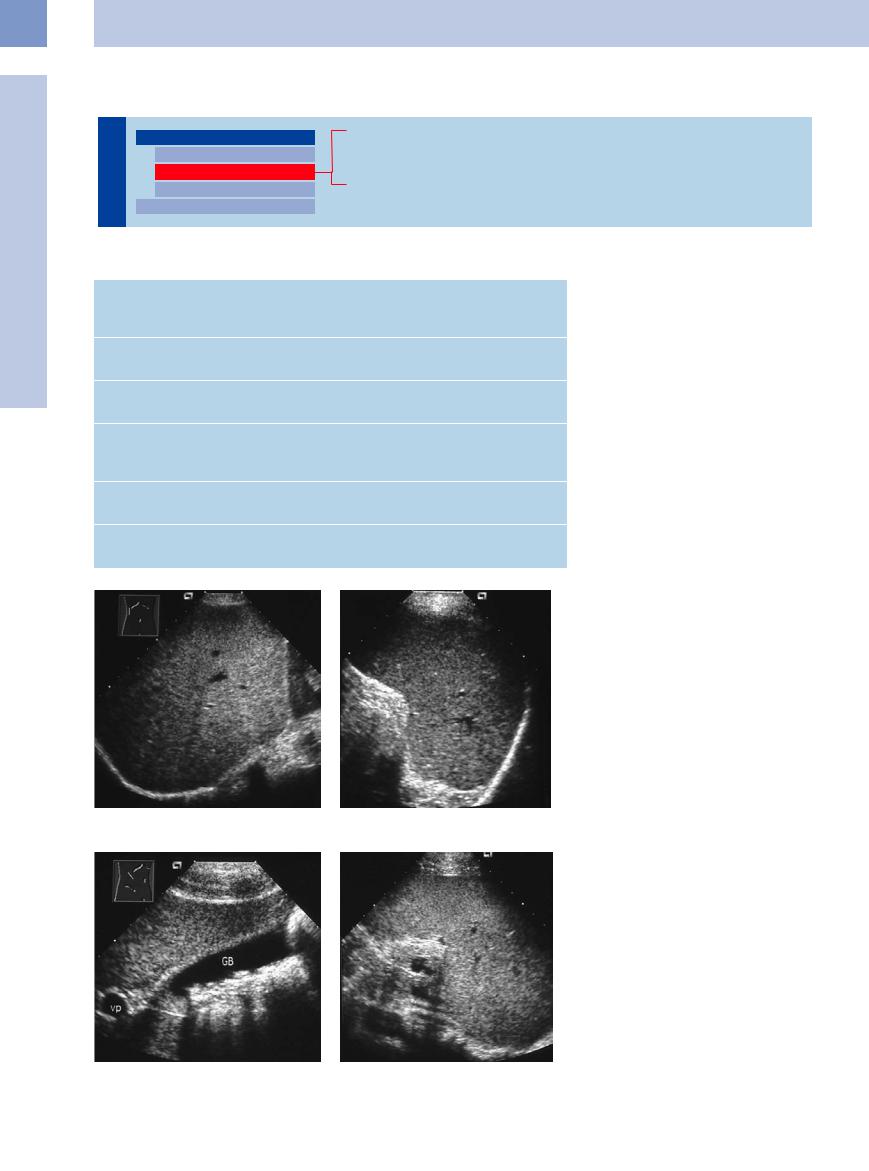

Table 5.1 Possible causes of splenomegaly

Acute and chronic systemic infection

Infectious mononucleosis, chickenpox, hepatitis, AIDS, sepsis, endocarditis, typhus, tuberculosis, malaria, toxoplasmosis, leishmaniasis, candidiasis

Disorders of the portal circulation

Hepatic cirrhosis, thrombosis of the portal and splenic veins, AV fistula of the spleen

Hemolytic disorders

Pernicious anemia, spherocytosis, thalassemia, sickle-cell anemia

Malignant systemic disease

Leukemia, myeloproliferative disorders, myelodysplastic syndrome, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, malignant histiocytosis, systemic mastocytosis

Immune disorders

Collagen disease, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, Evans syndrome

Other

Amyloidosis, Wegener disease, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis, lipidosis

Differential diagnosis of splenomegaly covers an extremely wide range of possibilities (Table 5.1). Experience tells us that any ultrasound study of the spleen is not by itself sufficient for pinpointing the definite cause of splenomegaly.

Severity. Although the size of the spleen may vary rather widely between patients with the same disease, assessing the dimensions of the organ may yield some differential diagnostic clues.

Mild to moderate splenomegaly is encountered, e. g., in infections and granulomatous disease (Fig. 5.17), portal hypertension (Figs. 5.20, 5.21), and acute leukemia.

Severe splenomegaly is typical of, e. g., malignant lymphoma, hemolytic anemia (Fig. 5.18), storage disease, infectious mononucleosis (Fig. 5.19), and leishmaniasis.

Extreme splenomegaly is seen in myelofibrosis, in terminal chronic myelocytic leukemia (CML; Fig. 5.23), and also in advanced lowgrade malignant lymphomas (Fig. 5.24). In some cases ultrasound may not be able to ascertain the exact size of the spleen.

Fig. 5.17a and b Hepatosplenomegaly in sarcoidosis. Hepatic involvement was confirmed by histology.

Fig. 5.18 A 40-year-old patient with spherocytosis.

a Frequently there are bilirubin gallstones in the gallbladder (GB) due to the chronic hemolysis.

b Splenomegaly. GB = gallbladder; VP = portal vein.

208

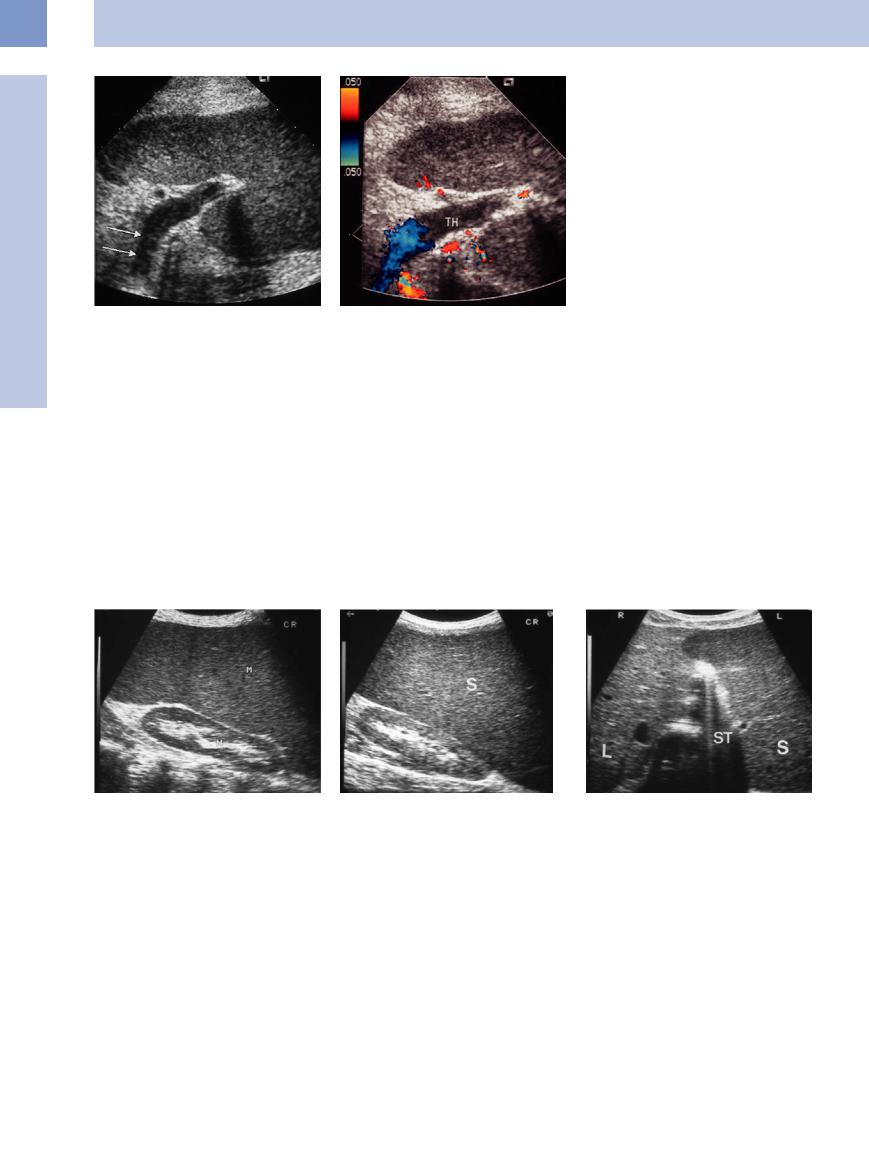

Infection

In viral or bacterial infections, moderate splenomegaly will sometimes display a slightly inhomogeneous splenic parenchyma without definite delineation of focal masses. In a few patients, infectious mononucleosis may be accompanied by extreme splenomegaly (Fig. 5.19). Complete resolution of this state may take months. Spontaneous splenic hemorrhage or rupture after inadequate incidental trauma has been reported in a rare few cases, mostly in spleens with rapidly enlarged volume.

Fig. 5.19 Infectious mononucleosis. |

b The splenic enlargement resolved over time |

a Marked splenomegaly (M). |

(3 months). |

Congestive Splenomegaly

Splenomegaly

Hepatic cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Splenomegaly is observed in 50–75% of patients with cirrhosis of the liver and portal hypertension (Fig. 5.20, Fig. 5.21). The causes are:

●Passive congestion (diminished portal venous outflow)

●Hypercirculation (increased splanchnic inflow)

●Intrinsic splenic factors (e. g., autoimmune processes)

This is counteracted by hemodynamically important portosystemic shunts, the extent of which may vary significantly from patient to patient. A regular-sized spleen does not rule out portal hypertension.

Splenic vein thrombosis. In thrombosis of the splenic vein, splenomegaly will be observed in approximately 60% of patients. A regular-sized spleen does not rule out splenic vein thrombosis. Ultrasound will visualize thrombosis of the

splenic vein as a homogeneously echogenic mass of varying severity within the lumen of the vessel (Fig. 5.22). Color-flow Doppler imaging will demonstrate the lack of flow as well as the collateral circulation and thus confirm the preliminary diagnosis.

Fig. 5.20 Cirrhosis of the liver.

a Hepatic cirrhosis (L) and ascites confirmed by histology. b Congestive splenomegaly (S).

Fig. 5.21 Congenital hypoplasia of the portal vein.

a Hypoplasia of the portal vein and esophageal varices. b Congestive splenomegaly.

5

Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

209

5

Spleen

Fig. 5.22 Partial thrombosis (TH) of the splenic vein. a Mild splenomegaly.

b Color-flow Doppler image.

Systemic Hematological Malignancy

Hematological Malignancy

Myeloproliferative disorder. Splenomegaly is regarded as the principal diagnostic sign in myeloproliferative disorders, particularly in myelofibrosis and CML (Fig. 5.23). It is found in approximately 70% of CML cases at the time of primary diagnosis, and after several years frequently results in an extremely large spleen. The number of circulating blast cells and the size of the spleen are decisive prognostic parameters.

High-grade lymphoma. In high-grade lymphoma, the size of the spleen is an unreliable

indicator of possible splenic involvement. Despite the fact that increasing splenic size will raise the probability of invasion by the lymphoma, a normal-sized spleen does not rule out possible involvement of the spleen.5

Low-grade lymphoma. In low-grade lymphoma, particularly in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL; Fig. 5.24), hairy cell leukemia, and also immunocytoma, splenomegaly will point toward a highly probable invasion of the spleen, even if the sonographic echo pattern of the organ is homogeneous. This has to

do with the fact that these entities are characterized by a leukemic course. Demonstration of splenomegaly is of prognostic significance, particularly in CLL.

Hodgkin disease. Use of splenic size as the sole criterion for possible involvement of the spleen has been abandoned. Approximately one-third of all affected spleens are normal in size. In contrast to almost all non-Hodgkin lymphomas, in Hodgkin disease the correlation between splenic size and extent of organ involvement is only tenuous.

Fig. 5.23 Extreme splenomegaly (M) in myeloproliferative |

Fig. 5.24 Hepatosplenomegaly (S) in CLL. |

b Both organs may touch in the upper abdomen (ST = |

disorder. |

a Ultrasound does not yield accurate dimensions of the |

stomach). L = liver. |

|

spleen. |

|

210