- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

8

Peritoneal Cavity

8.6 Differential Diagnosis of Benign and Malignant Ascites (Continued)

8.6 Differential Diagnosis of Benign and Malignant Ascites (Continued)

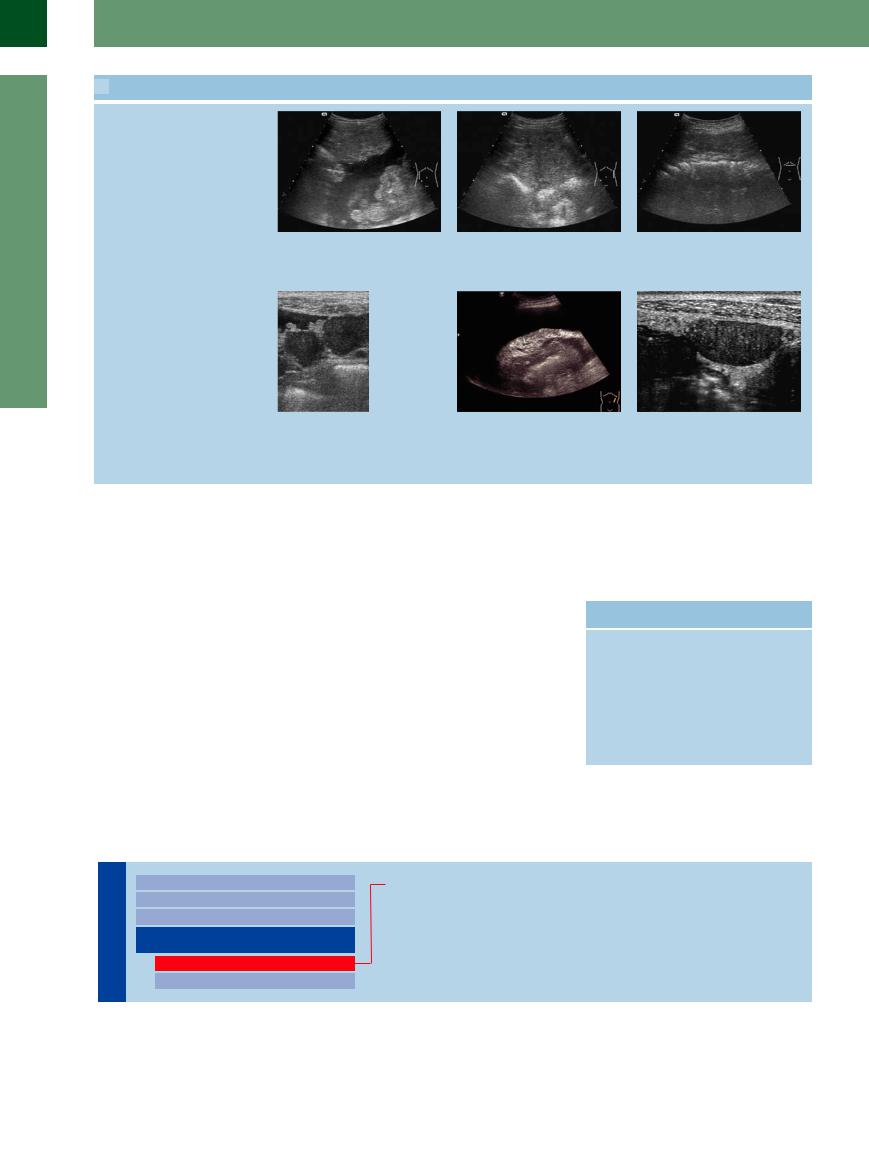

Peritoneal tumor masses

g Peritoneal tumor masses are a certain |

h Peritoneal carcinomatosis without as- |

i Increased separation of colon and ab- |

sign in the differential diagnosis: perito- |

cites (about 50%). Peritoneal tumor |

dominal wall because of the peritoneum |

neal carcinomatosis in advanced cancer of |

masses are the cardinal sign in sonogra- |

and greater omentum. This is a cardinal |

the colon. |

phy. |

sign even if ascites is not present. |

j Mesenteric and omentum metastasis respectively complete the complex image of peritoneal carcinosis.

k Thick hyperechoic induration resting on the stomach and surrounded by ascites caused by a gastric cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis (permission kindly granted by Dr. A Holle, University of Rostock, Germany).

l Hypoechoic solid nodule at the inner side of the abdomen wall, peritoneal carcinomatosis without ascites (permission kindly granted by Dr. A Holle, University of Rostock, Germany).

■ Differentiating Intraand Extraluminal GI Tract Fluid

In the differential diagnosis of intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal fluid the pathological collection of fluid within the GI tract plays a special role and therefore will be discussed separately. This topic includes especially the impaired intragastric and intraintestinal transport, where there is no definite peristalsis facilitating the assessment “within the GI tract lumen” but where the fluid simply sits (Table 8.8).

Assessment is possible when considering the following signs:

●Demonstration of the GI tract wall

●Peristalsis

●Characteristic localization and shape

●Characteristic intraluminal structures, e. g., haustration and the circular (Kerckring’s) folds

Table 8.8 Possible causes of impaired GI tract transport

Stomach Bowel

●Ulcer ● Peritoneal carcinomatosis

●Tumor ● Inflammatory stenosis

(Crohn disease)

●Tumor

●Intussusception

●Mechanical ileus (adhesions)

●Volvulus

Intragastric Processes

Cavity |

Diffuse Changes |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Localized Changes |

||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Wall Structures |

||

Peritoneal |

|||||

Differentiating Intraand Extraluminal |

|||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

GI Tract Fluid |

||

|

|

|

|

Intragastric Processes |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Intraintestinal Processes |

|

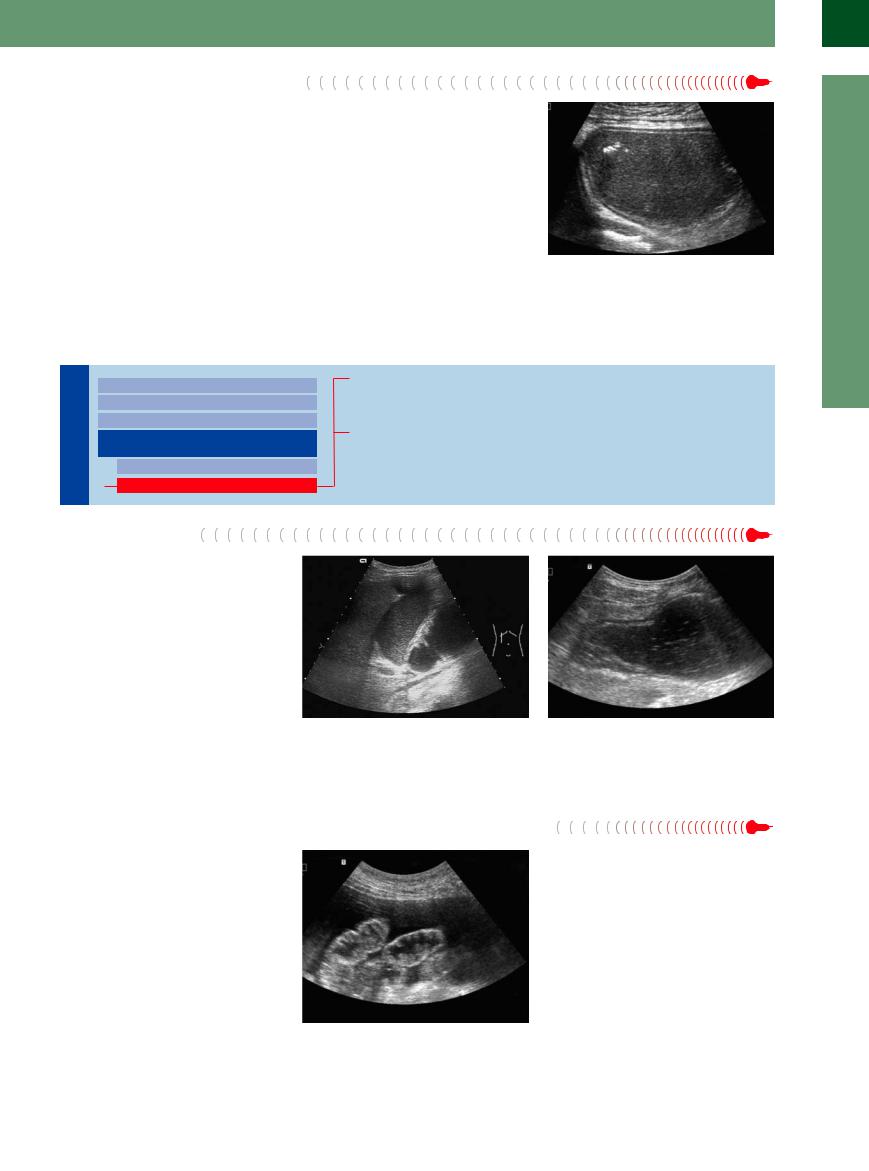

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

316

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

The stomach is easily delineated because of its location (subhepatic, anterior to the pancreas). A massively fluid-filled stomach concomitant with a lack of fluid in the duodenum suggests gastric outlet obstruction. With the upper abdomen upright, the liquid that will not drain becomes clearly visible, while the impeding gas will rise cephalad (gastric bubble, fornix). This disorder is characterized by small rising gas

bubbles producing the image of a “starry sky” with the paradoxical fact that there are not falling but rising stars (Fig. 8.50). The most common origins of gastric outlet obstruction are inflammatory stenosis (ulcers) and tumors. In this case ultrasound will be able to demonstrate the signs of a pathological gut signature (see Chapter 7, “Gastrointestinal Tract,”

Fig. 7.14).

Intraintestinal Processes

Fig. 8.50 Small gas bubbles rising in the massively fluidfilled stomach (fermentation), producing the image of the “star-studded stomach”: gastric outlet obstruction.

Peritoneal Cavity

Diffuse Changes

Localized Changes

Wall Structures

Differentiating Intraand Extraluminal

GI Tract Fluid

Intragastric Processes

Intraintestinal Processes

Duodenal Stenosis

Small-bowel Obstruction

Large-bowel Obstruction

Duodenal Stenosis

If impaired gastric emptying is accompanied by a rather distended and fluid-filled duodenum, while the other parts of the small and large intestine are without pathological findings, the stenosis or obstruction will be in the more distal duodenum (Fig. 8.51). This condition will always be accompanied by collections of fluid in the duodenum as well as the stomach, and the most common causes are tumors and inflammation at the head of the pancreas.

Fig. 8.51

a Duodenal stenosis: massive collection of fluid and distension of the duodenum (posterior to a hydropic gallbladder) in distal duodenal obstruction due to cancer of the pancreas.

b Distal duodenal obstruction is characterized by a fluidfilled stomach and distended duodenum, while the other sections of the small bowel do not exhibit any luminal filling.

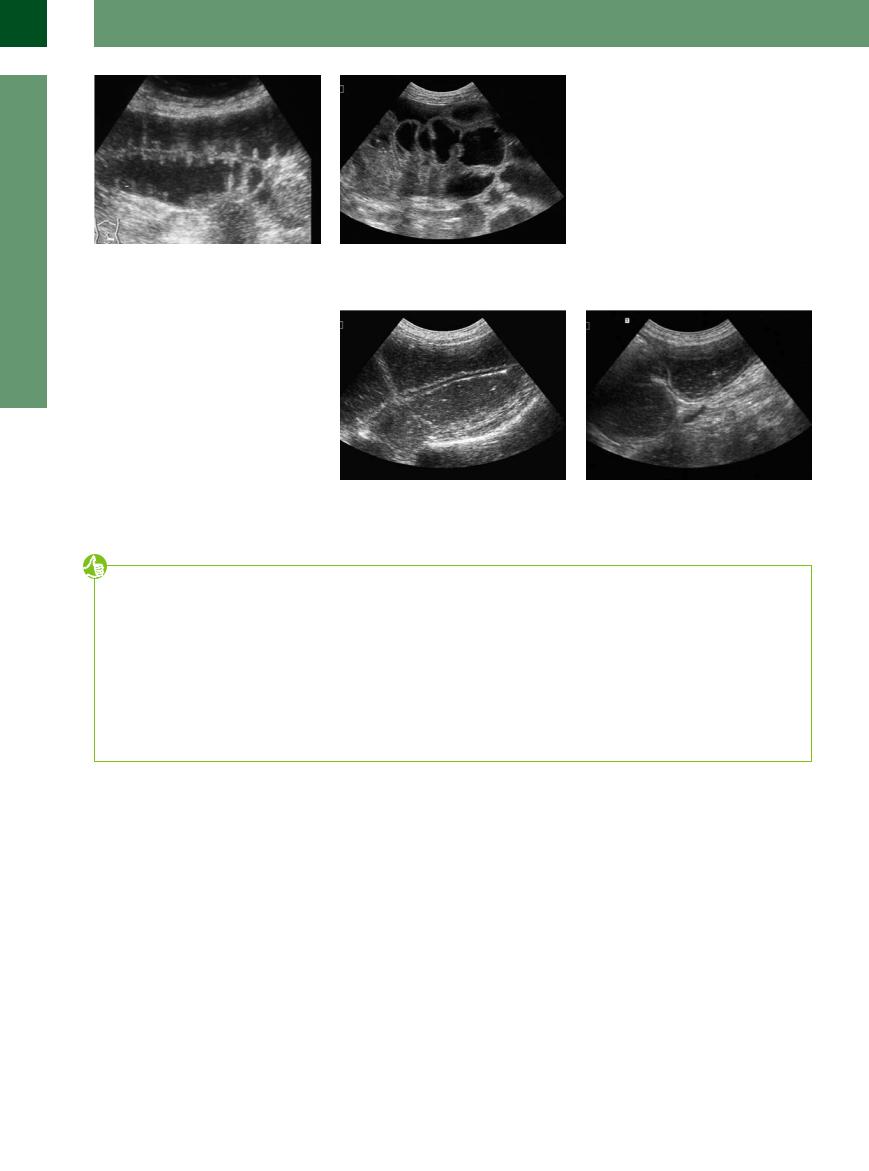

Small-bowel  Obstruction

Obstruction

Classic small-bowel obstruction is characterized by distended bowel loops with their typical circular folds, the so-called “piano key phenomenon” (Figs. 8.52, 8.53, 8.54). Depending on the stage and origin of the ileus, massive resistance-induced peristalsis, pendulating peristalsis, or no peristalsis at all can be demonstrated. The most common causes are inflammatory changes of the intestinal wall (see Chapter 7, Fig. 7.56, Fig. 7.57) and peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Fig. 8.52 Differential diagnosis is not always as easy, as in this case with its peritoneal carcinomatosis and ileus.

8

Differentiating Intraand Extraluminal GI Tract Fluid

317

8

Peritoneal Cavity

Fig. 8.53 Small-bowel obstruction. Distended intestine and the loops of the small bowel are identified by their circular folds projecting into the lumen, the so-called “piano key” or “Jacob’s ladder” phenomenon.

f Fig. 8.54 Small-bowel obstruction. Tentative “piano key phenomenon” in ileus due to peritoneal carcinomatosis in cancer of the pancreas. Also note the free ascites outside the bowel.

Large-bowel Obstruction

Obstruction

In the presence of a distended and rather fluidfilled intestinal lumen, large-bowel obstruction is characterized by the haustra coli and the typical course of the intestine (fixed colic position) (Fig. 8.55). The segments of bowel upstream will also be affected. The most common causes are tumors and inflammatory stenosis.

Fig. 8.55 |

b Severe large-bowel obstruction with demonstration of |

a Large-bowel obstruction: well-distended lumen and |

the ileocecal valve in a stenotic sigmoid mass. |

marked intraluminal fluid filling. |

|

Tips, tricks, and pitfalls

When considerable or massive amounts of as- |

measures such as puncture and cytology or lap- |

● Chronic inflammatory bowel disease during |

cites are produced in hepatogenic ascites or |

aroscopy are indicated if there is a suspicion of a |

an acute inflammation |

due to solid tumors the cause of the ascites is |

malignant ascites. |

● Appendicitis |

sonographically well documented. This is not the |

Small amounts of ascites (up to 5 mL and slightly |

● Ileitis |

case if the cause is a small nodular peritoneal |

more) pose a diagnostic problem. The following |

● Pancreatitis, cholecystitis |

carcinosis. Even contrast-enhanced ultrasound |

diagnosis should be considered: |

● Untreated celiac disease |

or CT angiography cannot detect micronodular |

● In women, ovulation (midcycle pain! History? |

|

metastases in the peritoneal cavity. They do not |

Sonographically, a medium–high endome- |

|

have any vessels, since they nourish themselves |

trium is a clue.) |

|

through the ascites. This is why other diagnostic |

● Small perforation, e. g., in diverticulitis |

|

References

[1]Görg C. Luft: “Akustischer Schlüssel” zur Diagnose! [Gas: “acoustic key” to the diagnosis]. Ultraschall Med 2002;23(4):233–238

[2]Rioux M, Michaud C. Sonographic detection of peritoneal carcinomatosis: a prospective study of 37 cases. Abdom Imaging 1995;20(1):47–51, discussion 56–57

[3]Thomas L. Diagnostik des Aszites In: Labor und Diagnose. 5th ed. Frankfurt/M.: THBooks Verlagsgesellschaft, 1998

[4]Totkas S, Schneider U, Schlag PM. Die besondere Herausforderung des seltenene Tumors. Chirurgische und multimodale Therapie des Pseudomyxoma peritonei [Surgical and multimodal therapy of Pseudomyxoma peritonei]. Chirurg 2000;71:869–876

[5]Kainberger P, Zukriegel M, Sattlegger P, Forstner R, Schmoller HJ. Sonographischer Nachweis des Pneumoperitoneums anhand typischer Sonomorphologie [Ultrasound detection of pneumoperitoneum based on typical ultrasound morphology]. Ultraschall Med 1994;15(3):122–125

[6]Nürnberg D, Mauch M, Spengler J, Holle A, Pannwitz H, Seitz K. Das sonografische Bild des Pneumoretroperitoneums als Folge einer retroperitonealen Perforation [Sonographical diagnosis of pneumoretroperitoneum as a result of retroperitoneal perforation]. Ultraschall Med 2007;28(6):612–621

[7]Gerbes AL, Jüngst D, Xie YN, Permanetter W, Paumgartner G. Ascitic fluid analysis for the differentiation of malignancy-related and nonmalignant ascites. Proposal of a diagnostic sequence. Cancer 1991;68(8):1808–1814

[8]Bilger R. Klinische abdominelle Ultraschalldiagnostik. Stuttgart: Fischer, 1989

[9]Beyer D, Mödder U. Diagnostik des akuten Abdomens mit bildgebenden Verfahren. Berlin: Springer, 1985

[10]Schölmerich J. Diagnostik und Therapie des Aszites [Diagnosis and therapy of ascites]. Internist 1987;28:448–458

[11]Meckler U, Hennermann KH, Caspary WF. Ultraschall des Abdomens. 3 rd ed. Cologne: Deutscher Ärzteverlag, 1998

[12]Rettenmaier G, Seitz KH. Sonographische Differentialdiagnose. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2000

318