- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

■ Nonvisualized Gallbladder

L. Greiner

Missing Gallbladder

Gallbladder |

Changes in Size |

Agenesis |

|

Wall Changes |

Post Cholecystectomy |

|

|

Intraluminal Changes |

|

|

|

Nonvisualized Gallbladder |

|

|

|

Missing Gallbladder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obscured Gallbladder |

|

|

Agenesis |

|

|

|

Although agenesis of the gallbladder is a rare |

|

|

|

anomaly (< 0.1%), it should be a primary con- |

|

|

|

cern in the differential diagnosis of the non- |

|

|

|

visualized gallbladder, because this would raise |

|

|

|

considerable (also forensic) doubts regarding |

|

|

|

the indication for surgery, even if the organ is |

|

|

|

found during exploration. |

|

|

|

Post Cholecystectomy |

|

|

|

In routine studies, nonvisualization of the gall- |

differential diagnosis and will elucidate the sit- |

explained as hematoma/seroma (Fig. 3.68) |

|

bladder most likely equates with a status post |

uation quickly. Apparently persistent gallblad- |

which will clear quickly. Only in rare cases do |

|

cholecystectomy (Fig. 3.67); obtaining a thor- |

ders in the immediate postoperative follow-up |

they have to be evacuated by ultrasound- |

|

ough patient history is still essential for proper |

are not especially infrequent, and are easily |

guided aspiration. |

|

3

Nonvisualized Gallbladder

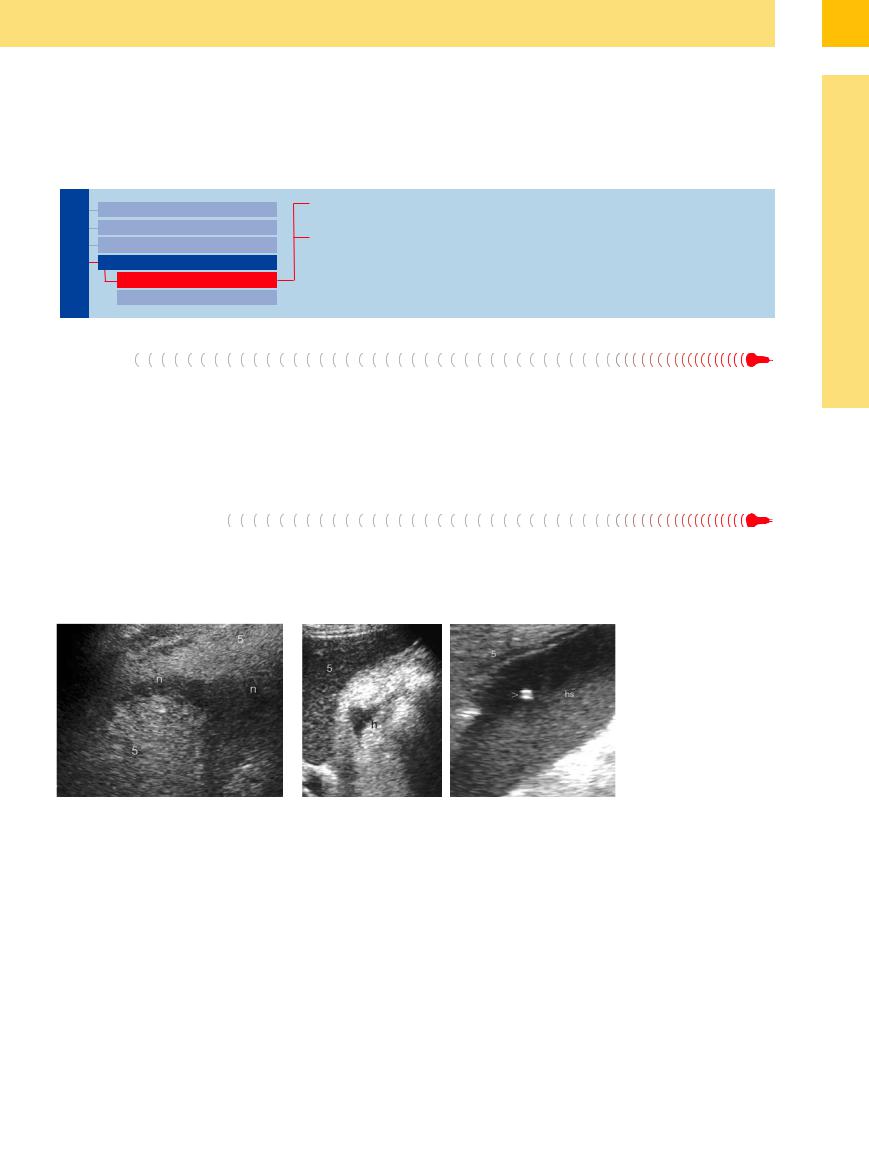

Fig. 3.67 Scar tissue (n) years after cholecystectomy; 5 = |

Fig. 3.68 Status post cholecystectomy. Left: Small hematoma (h) a few days |

liver. |

after cholecystectomy. Right: Hematoseroma (hs) 2 days post laparoscopic |

|

cholecystectomy, ultrasound-guided aspiration (for diagnosis and therapy). > |

|

= needle tip artifact; 5 = liver. |

163

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

Obscured Gallbladder

|

|

|

|

|

Changes in Size |

|

Isoechogenicity with Surrounding Tissue |

||

Gallbladder |

|||||||||

Wall Changes |

|

Malposition |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intraluminal Changes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Nonvisualized Gallbladder |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Missing Gallbladder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obscured Gallbladder |

|

|

|

Usually, maximum contraction of the postprandial gallbladder after oral intake does not present any problems, and nor does the gallbladder void of fluid due to lithic obstruction of the cystic duct (Fig. 3.69).

If the gallbladder is present but cannot be visualized on ultrasound, this may have to do with the gallbladder itself, its surroundings, or the operator (or a combination of all three). In this case:

●the gallbladder cannot be differentiated very well from adjacent structures, e. g., because of unusual content or consumed wall and lumen structure; or

●it is outside the “realm of imagination” of the operator, i. e., it is located in unusual ectopic sites.

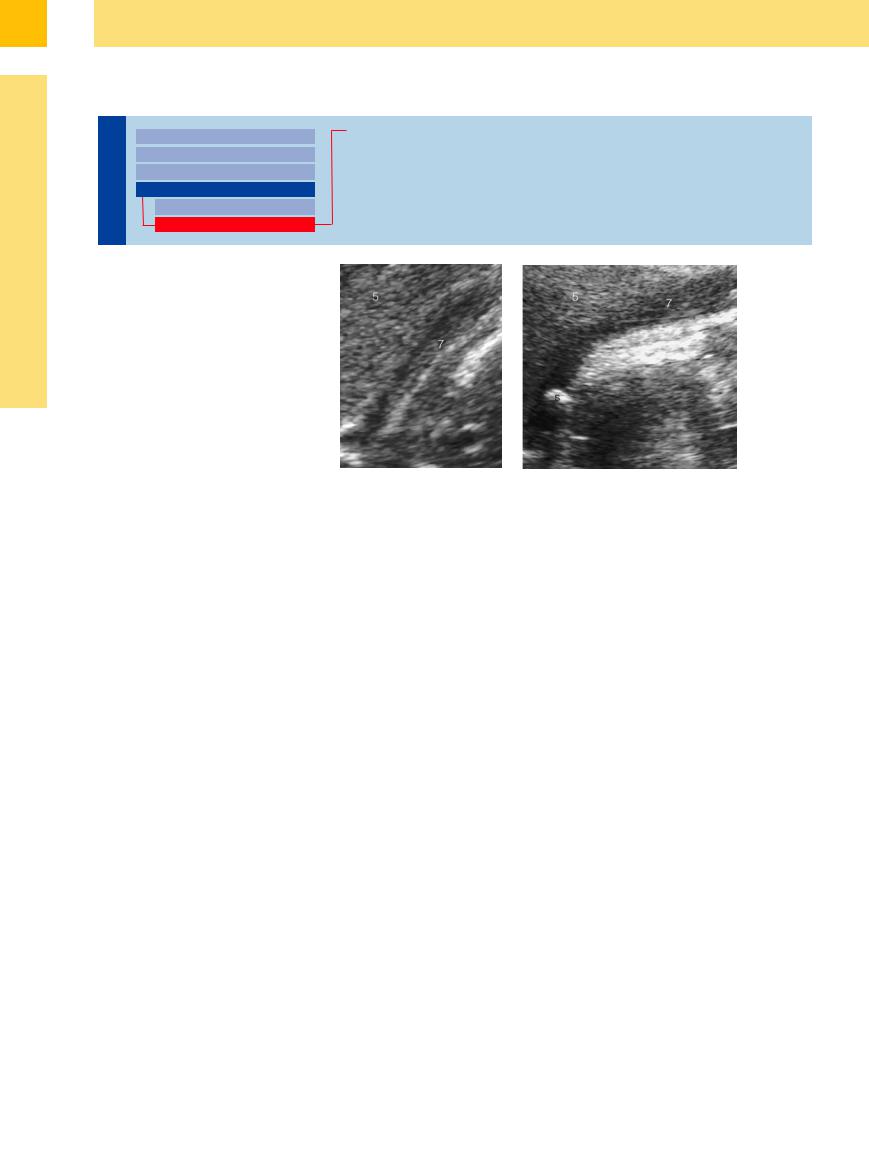

Fig. 3.69 Left: pronounced postprandial contraction of the gallbladder (7); 5 = liver. Right: Gallbladder atrophy (7) in cholelithiasis with calculous obstruction (s).

Isoechogenicity with Surrounding  Tissue

Tissue

Ultrasound may not be able to visualize the gallbladder if it is very small by nature or if it displays maximum volume reduction because of chronic inflammation (Fig. 3.70). Somewhat more common is the combination of (calculous atrophic) gallbladder (Fig. 3.71) and heavy tympanites (the latter may hinder a study, although any statement to this effect should be taken with a grain of salt).

Most problems in the differential diagnosis result from a gallbladder that is relatively isoechoic with the surrounding tissue and with homogeneous sludge resembling hepatic parenchyma (Fig. 3.70), and those gallbladders void of fluid that are being consumed by their own malignancy (Fig. 3.72, Fig. 3.73) or another, most commonly HCC (Fig. 3.74). This is also true if the gallbladder becomes part of a

cystic tumor (e. g., extensive ovarian cancer) or if it cannot be delineated from multicystic processes of the kidneys and/or liver, as well as (much less often) in extreme portal hypertension or cavernous transformation of the portal vein.

Malposition

Malposition of the liver, and thus of the gallbladder, in severe kyphoscoliotic deformity of the chest or paralysis of the right phrenic nerve may limit the accessibility of the gallbladder to ultrasound. Unusual (ectopic) location of the gallbladder is more common than originally thought; in elderly people, the gallbladder may hyperextend all the way into the minor

pelvis to be visualized only there. The same holds true for very slim, young patients in left lateral decubitus position: here, the pendulous gallbladder, resembling the clapper of a bell, may reach far into the left upper quadrant.

Abnormal locations resulting in poor or even impossible differentiation may be encountered in gallbladders deeply retracted in the portal

hilum or in intrahepatic gallbladders, which may then be misdiagnosed as focal liver lesion, particularly so in the case of cholecystolithiasis. Finally, visualization of the gallbladder in a patient with transposition of the viscera (situs inversus) may also present initial unfamiliar difficulties.

164

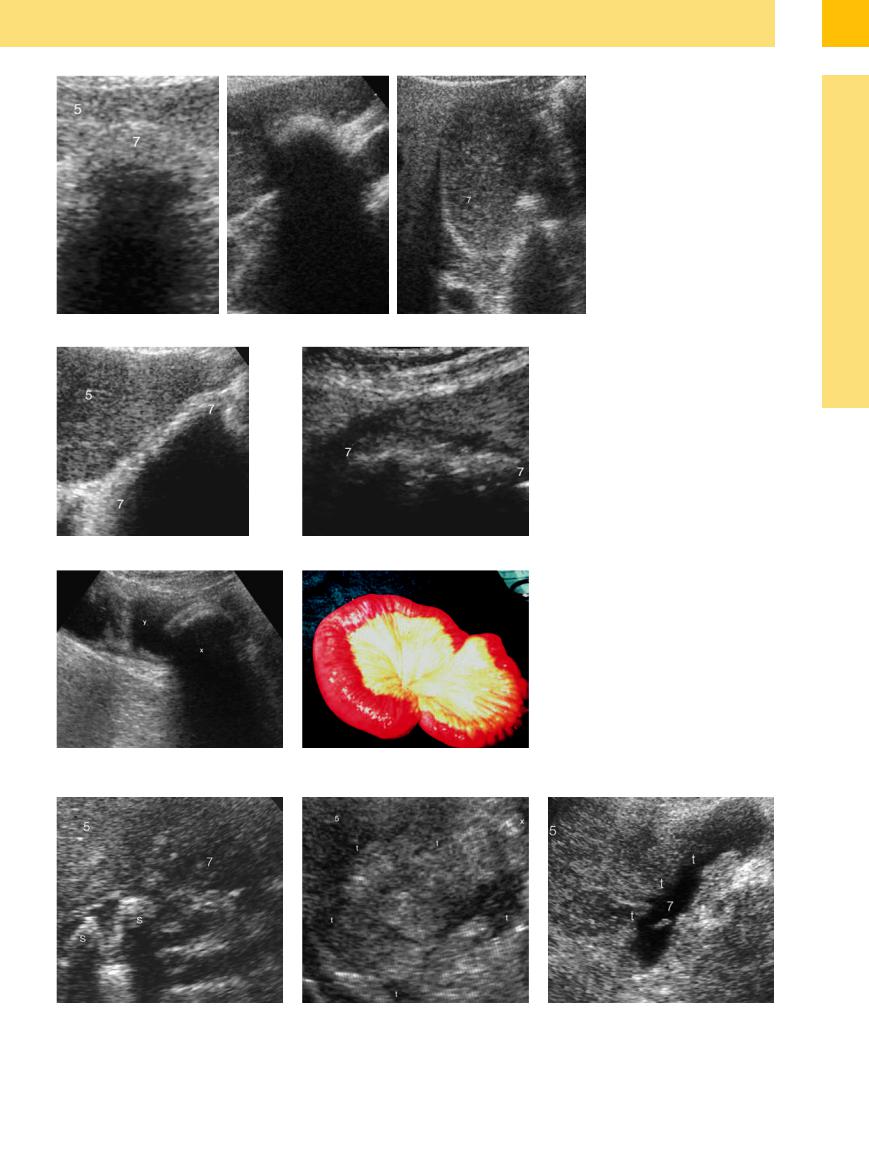

Fig. 3.73

a Atrophic calculous gallbladder (7) (stones S) with in- flammatory?–malignant? infiltration of the liver (5).

b Gallbladder carcinoma (confirmed by needle aspiration biopsy) with tumor infiltration (t) of the liver (5).

Fig. 3.70

a Bile stone with weak echo, almost impossible to demonstrate, in an atrophic gallbladder (7); 5 = liver.

b Small atrophied gallbladder (7); the stone can only be demonstrated indirectly by its shadowing; 5 = liver.

c “Hepatized” gallbladder (7) isoechoic with the liver (5).

Fig. 3.71 a and b Gallbladder void of liquid with atrophy

(7) in cholecystolithiasis and tympanites; 5 = liver.

Fig. 3.72

a Gallstone ileus (x) after perforation into the small bowel

(y).

b Operative site.

Fig. 3.74 Tumor infiltration (t) of the gallbladder (7) by hepatocellular carcinoma; liver (5).

3

Nonvisualized Gallbladder

165

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

Tips, tricks, and pitfalls

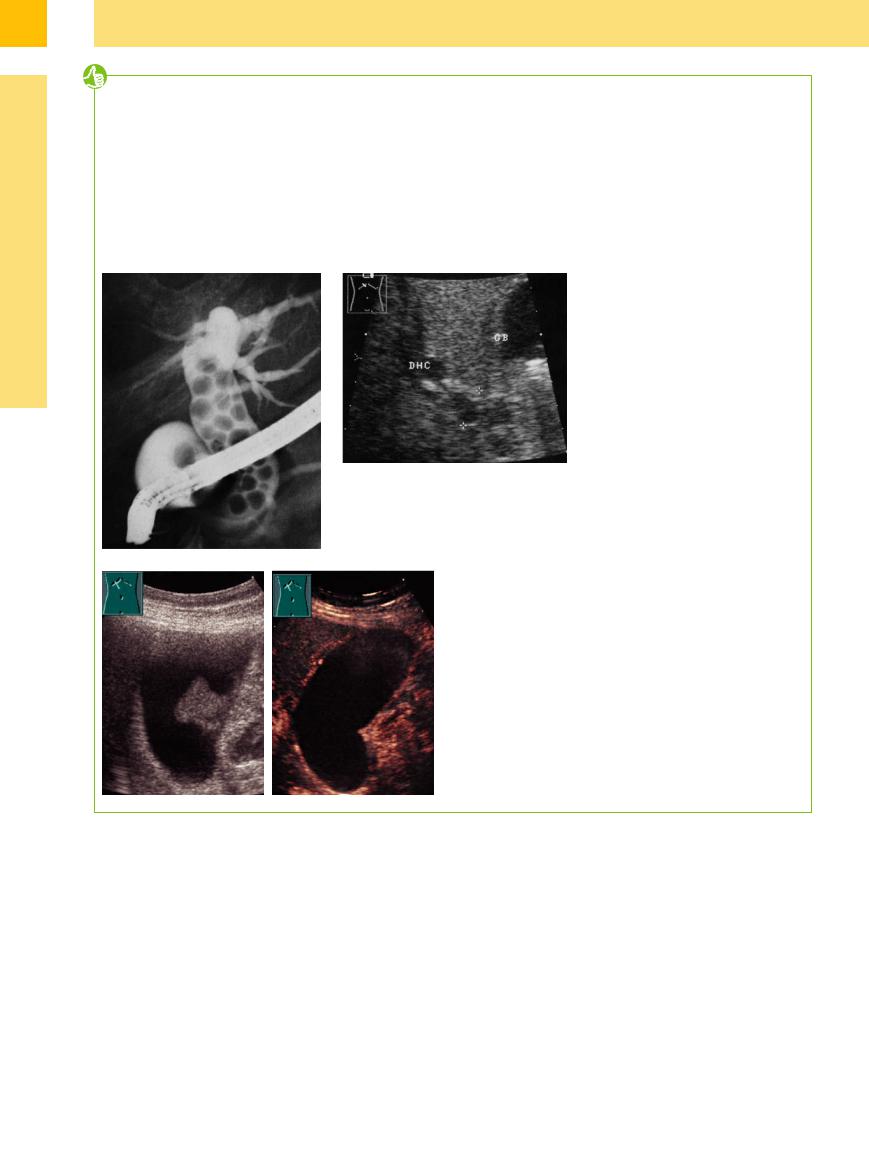

The detection of stones in a dilated CBD has a sensitivity of 82% and a high specificity. Under difficult conditions, in the case of prepapillary stones and numerous stones filling up the complete CBD, stone detection drops to 38% (Fig. 3.75a,b). The reduction is caused by the lack of fluid collection within the CBD.

If a strictly longitudinal scan direction is employed in the right upper abdomen, the middle

part of the CBD is to be found in the dorsal portion of the pancreatic head. The prepapillary duct is better detectable by turning the probe slightly to the right side. This segment is the domain of endoscopic ultrasound, with an accuracy of 100%.

Another difficulty may result in a partially or completely sludge-filled CBD; the differential diagnosis should include a bile duct carcinoma,

which is sometimes impossible to differentiate even by CT/MRI. CEUS is helpful in this condition. CEUS is the most rapid and reliable procedure to differentiate sludge in the gallbladder in the differential diagnosis of a malignant tumor (Fig. 3.76).

Fig. 3.75

a ERC: choledocholithiasis with multiple calculi.13

b Ill-defined dilated CBD (DHC) caused by multiple calculi without shadowing.13

Fig. 3.76 Differential diagnosis of sludge/tumor.

a Gray-scale image: tumorous wall-adherent sludge? Tumor?

b CEUS: lack of enhancement: unequivocal diagnosis of sludge.

References

[1]Börsch G, Wedmann B, Brand J, Zumtobel V. Aussagefähigkeit der präund postoperativen Sonographie in der Gallenchirurgie. Eine prospektive Studie [The significance of preoperative and postoperative sonography for biliary tract surgery. A prospective study]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1985; 110(36):1359–1364

[2]Braun U, Pospischil A, Pusterla N, Winder C. Ultrasonographic findings in cows with cholestasis. Vet Rec 1995;137(21):537–543

[3]Campbell WL, Ferris JV, Holbert BL, Thaete FL, Baron RL. Biliary tract carcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis: evaluation with CT, cholangiography, US, and MR imaging. Radiology 1998;207(1):41–50

[4]di Carlo I, Sauvanet A, Belghiti J. Intrahepatic lithiasis: a Western experience. Surg Today 2000;30(4):319–322

[5]Contractor QQ, Boujemla M, Contractor TQ, el-Essawy OM. Abnormal common bile duct sonography. The best predictor of choledocholithiasis before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Clin Gastroenterol 1997;25(2): 429–432

[6]Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1992;215(1):31–38

[7]Braun G. Schwerk (eds.). Ultraschalldiagnostik. Lehrbuch und Atlas 111-1.1 Biliäres System. Ecomed, 1993.

[8]Jakobeit C, et al. Probleme der sonographi-

schen Verlaufskontrolle nach ESWL von Gallenblasensteinen. Ultraschall Klin Praxis 1989;(Suppl.1):20

[9]Imhof M, Teetzmann A, Ohmann, C. Sonomorphologie der Streßcholezystitis. Ultraschall Med 1992;13:96–101.

[10]Heyder N, Günter E, Giedl J, Obenauf A, Hahn EG. Polypoide Läsionen der Gallenblase [Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1990;115(7):243–247

[11]Piscaglia F, Nolsøe C, Dietrich CF, et al. The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Practice of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS): update 2011 on non-hep- atic applications. Ultraschall Med 2012; 33(1):33–59

[12]Jakobeit CH, Rebensburg S, Greiner L. Sonographische Gallensteinmorphologie [Ultrasound morphology of gallstones]. Z Gastroenterol 1992;30(9):594–597

[13]Schmidt G, Ed. Ultraschall-Kursbuch. 3 rd ed. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1999.

[14]Rettenmaier G, Seitz K, Eds. Sonographische Differentialdiagnostik. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2000

166