- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

2

Liver

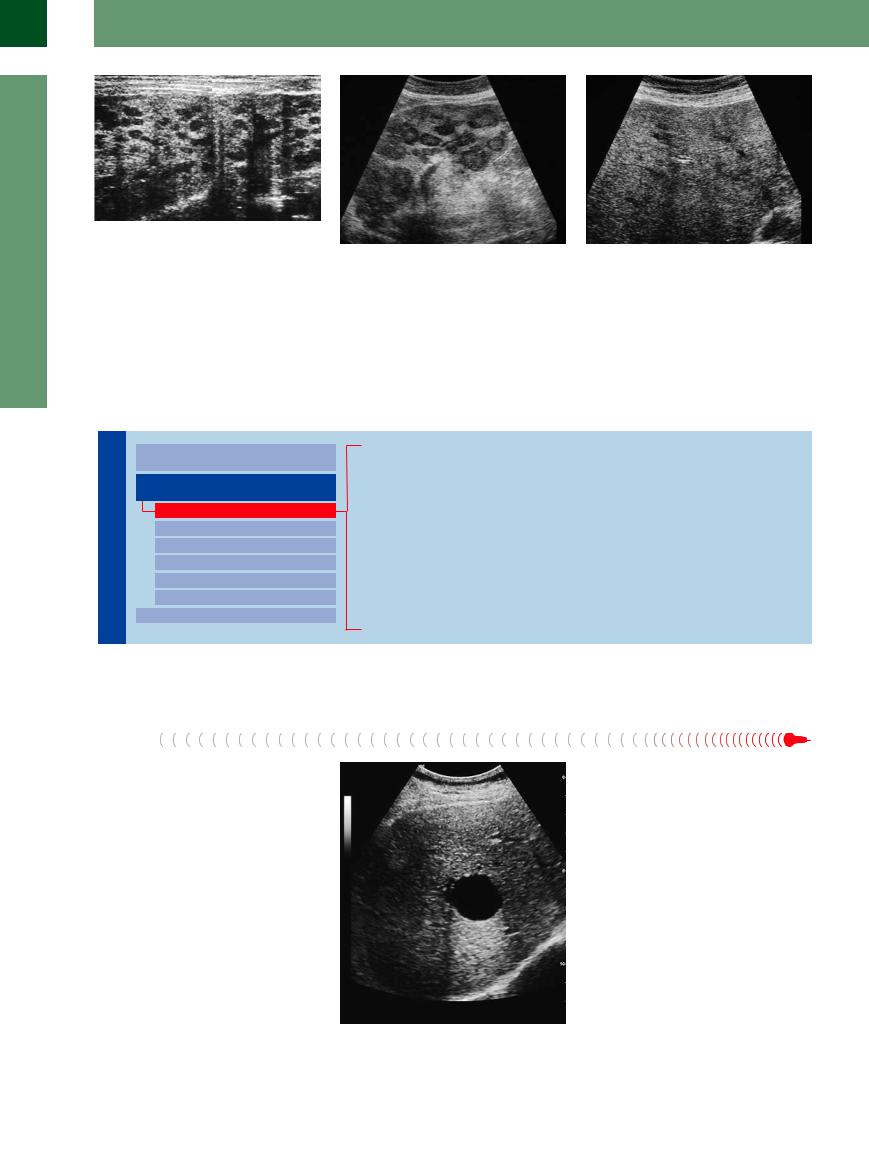

Fig. 2.54 Criterion: change/activity of a mass; in this case, the same small cell lung cancer as in Fig. 2.53 after two cycles of chemotherapy with the ACO protocol; the metastases have grown in size and have a distinct halo (zone of active tumor growth) and echogenic material (necrosis) in the center. Note the increased echogenicity of the hepatic parenchyma resulting from the toxic steatosis induced by the chemotherapy.

Fig. 2.55 Criterion: change/activity of a mass; in this case, the same small cell lung cancer as in Fig. 2.54 after four cycles of chemotherapy with the ACO protocol; there is a hint of diffuse infiltration although no definite focal metastatic transformation can be seen except in a few questionable places; complete remission clinically.

Fig. 2.56 Metastatic spread in the liver: small hyperechoic masses; on further development, they become a central hypoechoic transformation by liquefaction, and between these ring-shaped tissue.

Anechoic Masses

|

|

|

Diffuse Changes in Hepatic |

|

Liver |

Parenchyma |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Localized Changes in Hepatic |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Parenchyma |

|

|

|

|

|

Anechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hypoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Isoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hyperechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Echogenic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Irregular Masses |

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions |

|

|

|

|

||

Cysts

Polycystic Liver Disease

Hemorrhage/Hematoma

Bilioma

Abscess

Hydatid Cysts

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia/Hepatic Peliosis

Lipoma

Lymphoma

Metastases

Vessels/Bile Ducts

Anechoic masses in the liver are either pure fluid-filled cavities or masses with very few or weakly reflecting (hardly discernible) boun-

Cysts

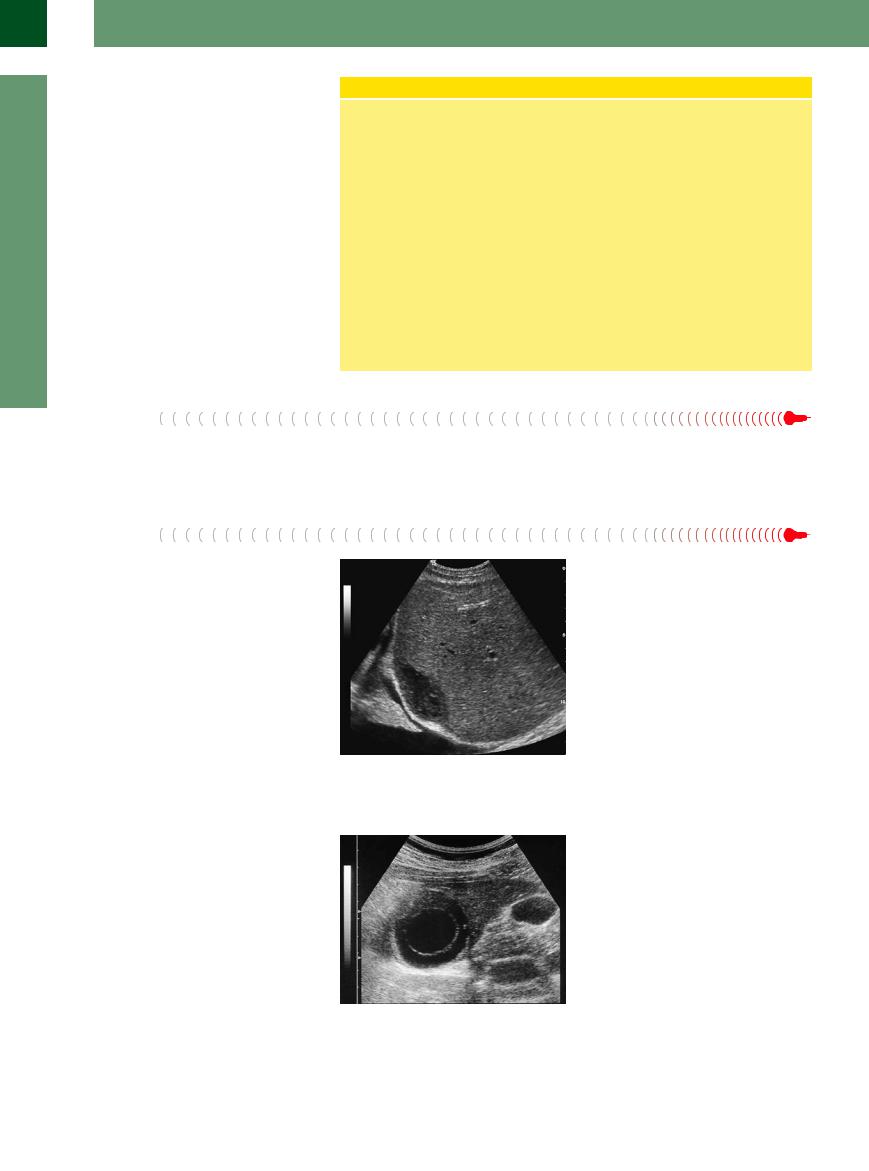

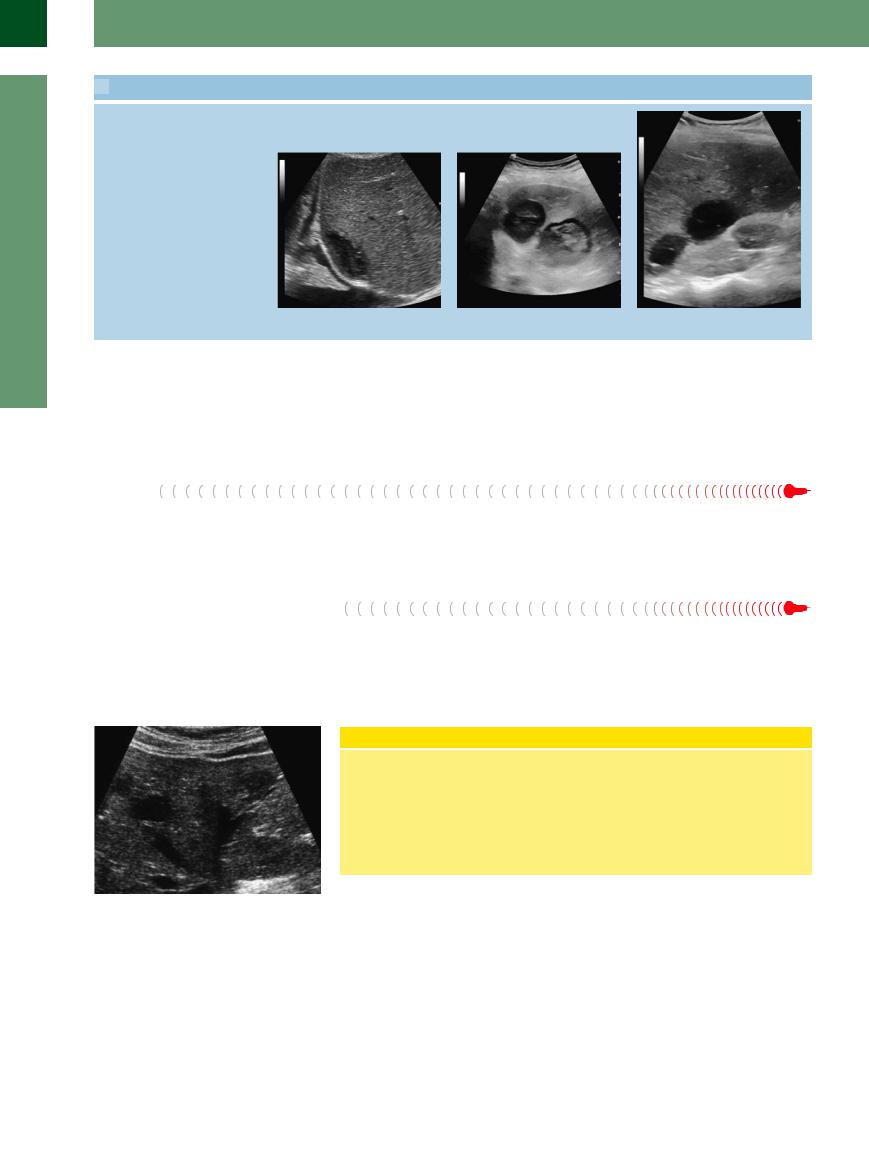

Intrahepatic cystic masses (Figs. 2.57, 2.58, 2.59,  2.8a–f) may be unilocular or multiple, may vary in size (a few millimeters to > 10 cm), and may be found anywhere in the liver.

2.8a–f) may be unilocular or multiple, may vary in size (a few millimeters to > 10 cm), and may be found anywhere in the liver.

Unilocular cysts are round and smooth, and the lumen is absolutely without any echoes. Since the lumen of the cyst does not attenuate the ultrasound beam, unilocular cysts demonstrate posterior enhancement that is not always easy to detect in the near field, at large depths, and in very small masses. The walls of unilocular cysts do not exhibit any echotexture, and they may elevate a surface or protrude above it, but do not cross segmental boundaries. Neither B-mode ultrasonography nor CEUS can detect vascularization in the cystic wall or lumen, and the adjacent parenchyma of the liver appears absolutely normal. In cases

daries. The sonographer should always bear in |

tion would be comparison with the vascular |

mind the possibility of inadequate presettings |

lumen. |

of the equipment (insufficient gain)—one op- |

|

Fig. 2.57 Solitary cyst in the right hepatic lobe: smoothmargined wall, anechoic lumen; so-called posterior enhancement (= reduced attenuation of the ultrasound beam after passing the cyst).

88

of multiple true cystic masses, the differential diagnosis of polycystic liver disease should not be overlooked.

Fig. 2.58 Large liver cyst on the lateral right side. |

Fig. 2.59 Solitary cysts; four cysts in the right hepatic |

|

lobe, one reaching the liver surface is anechoic with |

|

typical posterior enhancement, the others in central po- |

|

sition. |

Polycystic Liver Disease

This autosomal dominant disease may be limited just to the liver but can involve the kidneys and/or the pancreas as well. With age, the liver is permeated by an uncountable number of cystic masses in the liver (Figs. 2.60, 2.61, 2.62, 2.8 g,h). Initially, the cysts may be quite small but later they vary in size. In the end, this leads to an enormous increase in the size of the organ (all the way into the small pelvis). The

2.8 g,h). Initially, the cysts may be quite small but later they vary in size. In the end, this leads to an enormous increase in the size of the organ (all the way into the small pelvis). The

liver is firm, tightly elastic, and tender (capsular tension) and its surface is covered by a myriad protruding cysts. Regular segmental anatomy and the shape of the liver have disappeared altogether. The image is dominated by the cysts, and in the terminal stage of the disease hardly any parenchyma can be demonstrated. The gallbladder is differentiated (best after a meal) from the cysts by its triple-layered

wall since, although the cysts are lined by a simple columnar epithelium, they do not exhibit any wall structures. Complications may arise from hemorrhage into or infection of the cysts; apart from the clinical sign of local tenderness it may alter/increase the echogenicity of the pathological cystic contents.

Fig. 2.60 Cysts and gallbladder. Compared with the gall- |

Fig. 2.61 Polycystic liver disease. The hepatic parenchyma |

bladder wall, the cystic masses in polycystic liver disease |

is permeated by numerous cysts; typical “blooming” of |

do not display any echotexture in the wall. |

the meager remaining parenchyma, caused by the dimin- |

|

ished attenuation. |

Hemorrhage/Hematoma

Hemorrhage or localized hematoma (Fig. 2.63,  2.8 p–r) may be due to local trauma, e. g., needle biopsy, stab wound, or rupture of healthy adjacent tissue, and is different from bleeding into an existing lesion (e. g., adenoma, metastasis). Typically, a recent hematoma is anechoic and exhibits a smooth boundary with the surrounding tissue; in cases of major parenchymal rupture, the shape could become irregular and even bizarre. Subcapsular hemorrhage may lift the capsule off the liver like a tent. The bleeding is characterized by a less than optimal posterior enhancement, and frequently the adjacent parenchyma displays a slight increase in echodensity due to compression artifacts. Older hemorrhages/hematomas

2.8 p–r) may be due to local trauma, e. g., needle biopsy, stab wound, or rupture of healthy adjacent tissue, and is different from bleeding into an existing lesion (e. g., adenoma, metastasis). Typically, a recent hematoma is anechoic and exhibits a smooth boundary with the surrounding tissue; in cases of major parenchymal rupture, the shape could become irregular and even bizarre. Subcapsular hemorrhage may lift the capsule off the liver like a tent. The bleeding is characterized by a less than optimal posterior enhancement, and frequently the adjacent parenchyma displays a slight increase in echodensity due to compression artifacts. Older hemorrhages/hematomas

Fig. 2.62 Polycystic liver disease. Finding during laparoscopy.

Fig. 2.63 Subcapsular hematoma in the posterior face of the left hepatic lobe; guided-needle biopsy under sonography.

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

89

2

Liver

lose their anechogenicity: the bleeding becomes organized, first with hypoechoic and later with hyperechoic intraluminal thrombi, which may appear in bizarre lumps and strands.

Hemorrhage/Hematoma

Hemorrhage. Bleeding in the liver may be due to inadvertent trauma, iatrogenic injury (needle biopsy, drainage), or coagulation disorder, or it may complicate a preexisting mass (e. g., adenoma). The typical finding is a hypoechoic to anechoic liquid mass; in rare cases (due to compression) it is homogeneously hyperechoic. The mass caused by a hemorrhage is sharply delimited and sometimes irregular in shape; the surrounding tissue is compressed (increased echogenicity), and quite often the patient is in pain (capsular tension).

Older hemorrhage. Apart from irregular liquid regions, these demonstrate inhomogeneous echogenic areas corresponding to clots, strands of fibrin, and different stages

of organization in the hemorrhage. Subcapsular bleeding may come from ruptured parenchyma with irregular borders and end up as perforation and massive hemorrhage into the abdominal cavity (demonstration of free fluid in the abdominal cavity).

Capsule injuries. In ultrasonography, injuries solely to the capsule of the liver are detected as gaps in the hepatic contour; however, frequently this direct sign is impossible to demonstrate and the sonographer has to rely on the indirect sign of free fluid in the abdominal cavity increasing in volume during frequent follow-up scans.

Bilioma

It is not possible to differentiate between acute bleeding and collections of bile that may also gather as a result of liver trauma and display the same sonographic characteristics ( 2.8n).

2.8n).

Abscess

An abscess may present as an anechoic mass with distinct posterior enhancement (Fig. 2.64,

2.8x–z).

2.8x–z).

Fig. 2.64 Abscess, subdiaphragmatic in the right liver lobe; not quite anechoic, slight posterior enhancement; impression of the diaphragm, atelectasis of the basal lung.

Hydatid Cysts

Hydatid cysts are parasitic cysts of Echinococcus granulosus and may be present in the liver as solitary or multiple cysts. Their typical appearance is that of cyst-within-cyst or as a conglomerate of cysts (Fig. 2.65, Fig. 2.66,  2.8 s–w). The lumen of the hydatid cyst is anechoic, and a layered cyst wall, akin to a capsule, is a typical finding. Demonstration of marginal daughter cysts (cyst-within-cyst) and calcification in the wall is pathognomonic for hydatid disease. Because of the wall thickness, posterior enhancement is less marked or may even be absent, and calcifications result in posterior shadowing. The morphological classification of hydatid disease is summarized in Table 2.14.

2.8 s–w). The lumen of the hydatid cyst is anechoic, and a layered cyst wall, akin to a capsule, is a typical finding. Demonstration of marginal daughter cysts (cyst-within-cyst) and calcification in the wall is pathognomonic for hydatid disease. Because of the wall thickness, posterior enhancement is less marked or may even be absent, and calcifications result in posterior shadowing. The morphological classification of hydatid disease is summarized in Table 2.14.

Fig. 2.65 Hydatid cyst. Typical cyst-within-cyst image in Echinococcus granulosus infection; located in segment VI of the right hepatic lobe; vital cyst, stage CE 1. Note the normal gallbladder (right side).

90

Fig. 2.66 Hydatid cyst in stage CE 3.

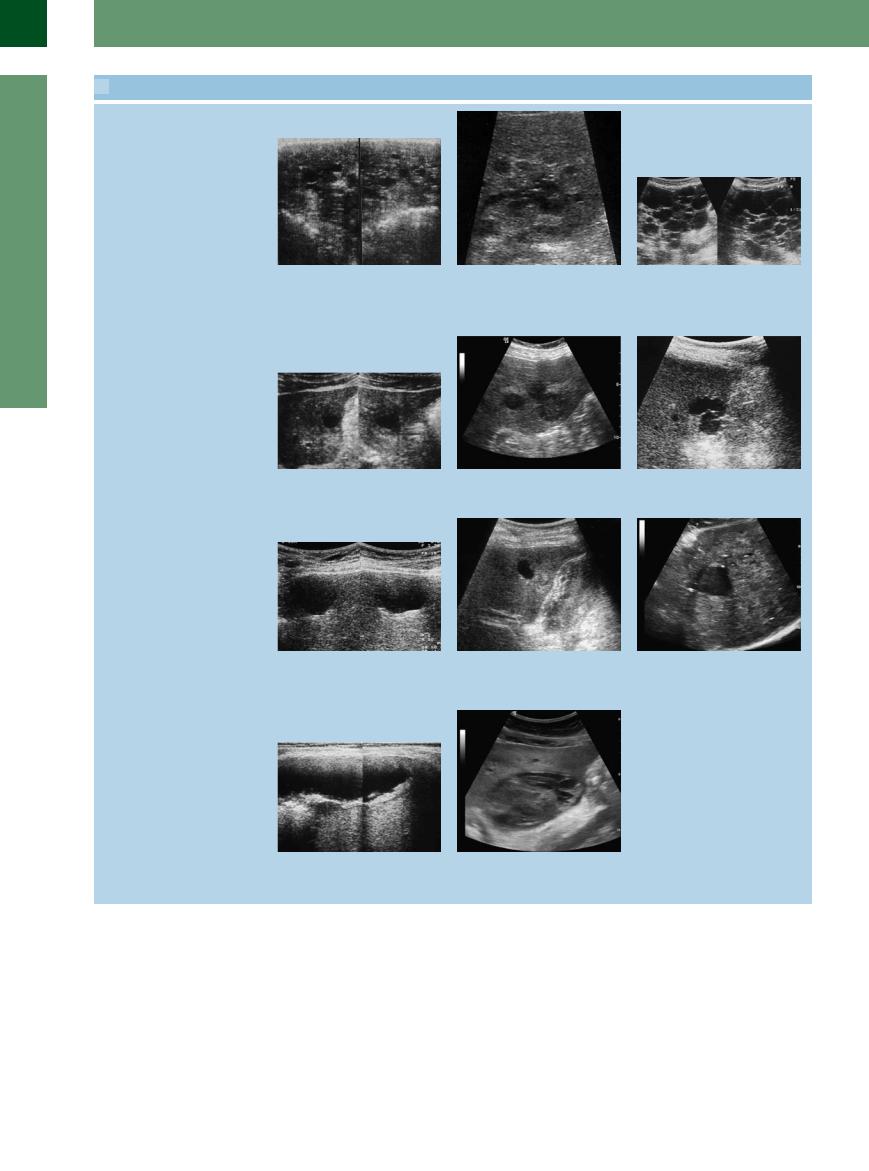

2.8 Cysts

2.8 Cysts

Solitary/simple cysts

Echinococcus Infection

Cystic echinococcosis, also known as unilocular hydatid disease, is due to Echinococcus granulosus (a parasitic tapeworm in canines). Alveolar echinoccocosis, terminating in alveolar hydatid disease, is due to Echinococcus multilocularis (parasitic in foxes and small rodents).

Ultrasonography of cystic echinococcosis demonstrates the characteristics of a complex cyst: thickened, sometimes layered cyst wall, akin to a capsule, with marginal daughter cysts (cyst-within-cyst) and calcification in the wall (pathognomonic). Because of the wall thickness, posterior enhancement is less pronounced or may even be absent, and in calcification there will be posterior shadowing. Old and no longer

vital hydatid cysts may present with different degrees of lumen degradation, bizarre membrane formation, irregular hyperechoic compaction, and also central calcification, or they may exist just as calcified remnants.

In alveolar echinococcosis (multilocular hydatid disease) there is diffuse poorly delimited infiltration of the hepatic parenchyma with inhomogeneous coarse texture, whose more advanced stages involve the vessels and bile ducts, may demonstrate calcification, and can spread from the liver to destroy the diaphragm, lungs, porta hepatis, retroperitoneum, duodenum, and pancreas.

Table 2.14 Morphological classification of cystic echinococcosis (CE)4,6 (WHO classification)

Stage |

Characteristics |

Activity |

CE 1 |

Univesicular cyst |

Active |

CE 2 |

Multivesicular cyst |

Active |

CE 3 |

Cyst with detached endocyst/daughter cysts |

Degenerative |

CE 4 |

Heterogenic solid cyst |

Inactive |

CE 5 |

Calcified cyst |

Inactive |

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

a Typical unilocular cyst with anechoic lumen, smooth margin without any structures: so-called posterior enhancement.

Multiple simple cysts

d Simple cysts may occur in multiples or clusters, or be disseminated.

b Small subcapsular cyst at the inferior face of the segment VI with protrusion of the surface.

e Solitary cysts: one is readily recognizable, the other is hypoechoic when encountered in tangential section.

c Tiny unilocular cyst anteriorly in segment III of the left hepatic lobe; owing to its small size, definite assessment as a cyst is not possible.

f Atypic, septated cysts in the left hepatic lobe with irregular walls in Caroli syndrome.

91

2

Liver

2.8 Cysts (Continued)

2.8 Cysts (Continued)

Polycystic syndrome

g and h Polycystic liver disease.

g Easy to diagnose owing to the number of cysts and the disturbed architecture of the organ.

h These findings may be taken for multiple simple cysts (early manifestation of a polycystic syndrome); in this case followsup are necessary.

i Polycystic liver disease with mediumsized cysts.

Differential diagnosis of cystic masses

j Small abscess in left hepatic lobe; hypoechoic reaction of the adjacent parenchyma.

m Amoebic liver abscess confirmed by fine-needle aspiration; note the unusual posterior enhancement.

Differential diagnosis of hypoechoic masses

p Differential diagnosis of hypoechoic mass. Large subcapsular hematoma/hemorrhage in HELPP syndrome with the capsule almost “torn off” the parenchyma.

k Metastases—lack of the posterior enhancement of the hypoechoic lesions.

n Accumulation of fluid along the intrahepatic canal of the fresh knife wound (history). Hemorrhage? Bilioma? Involvement of the gallbladder wall.

q Subcapsular hematoma after biopsy of the left liver lobe.

l Septated cyst, posterior cyst not quite anechoic—complication?

o Mass in a cirrhosis with posterior enhancement, but irregular margins and not completely anechoic—in this case HCC.

92

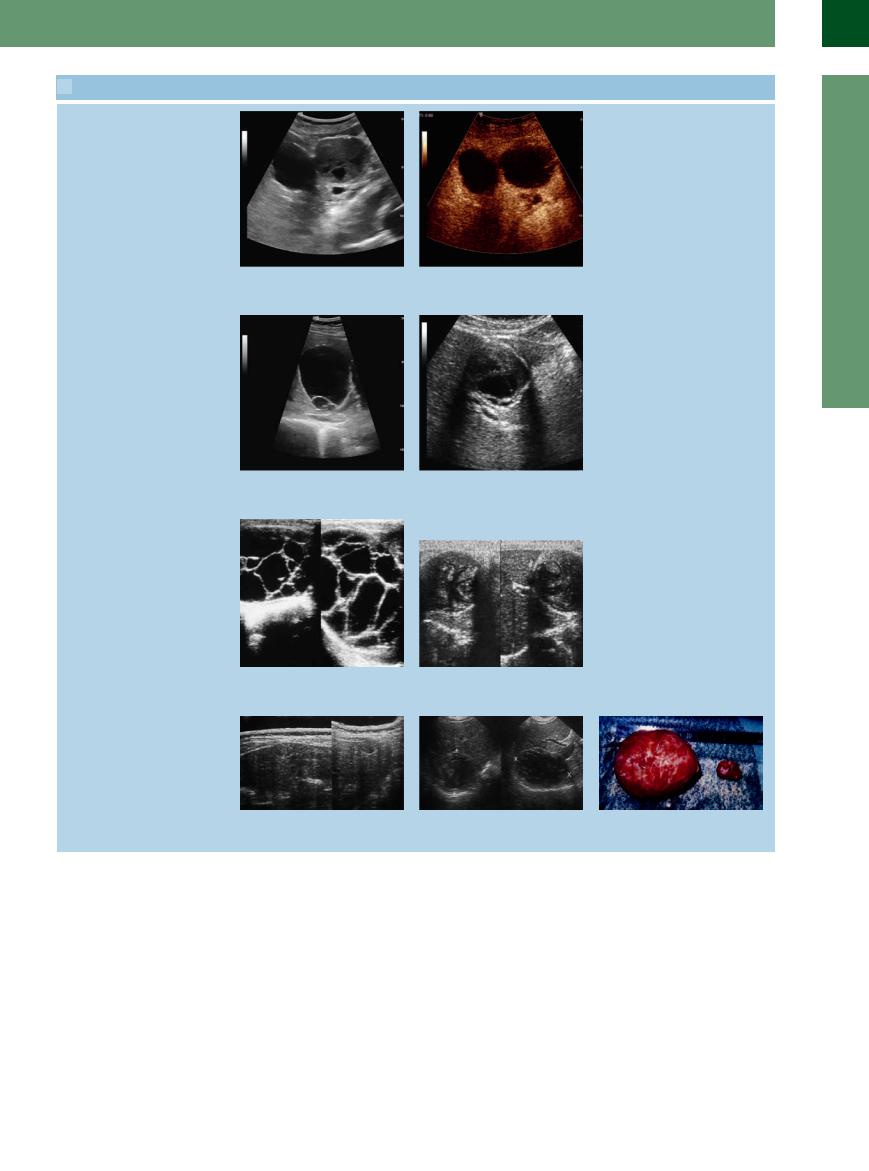

2.8 Cysts (Continued)

2.8 Cysts (Continued)

r Left and right: Hemorrhagic cyst in cystic liver disease; CEUS demonstrates nonenhancement in the hypoechoic mass, typical sign of a hemorrhagic cyst.

Hydatid disease

s and t Hydatid cyst. |

t Disintegration of the same cyst after two |

s “Cyst in cyst”; typical vital cystic echino- |

courses of albendazole. |

coccosis (WHO stage CE 2). |

|

u Heavily encapsulated polycystic lesion |

v Mixed structured cyst (WHO stage CE 4). |

with numerous septa and minor calcifica- |

|

tion. |

|

w Left and middle: Solid structured mass (WHO stage CE 4). Right: Resection specimen of the two hydatid cysts.

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

93

2

Liver

2.8 Cysts (Continued)

2.8 Cysts (Continued)

Abscesses: fresh abscesses are hypoechoic, nearly anechoic; increasing complications (e. g., gas) and sequestration cause structural changes

x Abscess in cholangitis with sepsis (gas in y Two different echoic abscesses. |

z Postoperative abscess. |

the bile duct). |

|

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia/Hepatic Peliosis

Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia/Hepatic Peliosis

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, also |

ence of arteriovenous malformations in the |

characterized by blood-filled lacunae separate |

known as Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome or |

liver, which yield a corresponding Doppler sig- |

from the portal circulation (see Fig. 2.69). |

Osler’s disease, is also associated with the pres- |

nal. This finding is absent in peliosis, which is |

|

Lipoma

Smooth margins and anechogenicity are not characteristic of lipomas, and posterior enhancement is not very marked. Most lipomas are found around the round ligament.

Lymphoma

Sometimes hepatic involvement in systemic lymphatic malignancy may result in anechoic masses in the liver. The intrahepatic masses accompanying lymphomas are frequently multiple, vary in size, and tend to be of irregular rather than round or oval shape (Fig. 2.67). One

typical feature is the simultaneous presence of the various stages of lymphatic infiltration: apart from solitary anechoic masses (no or slight posterior enhancement), there are often irregular areas of varying size with hypoechoic infiltration of the parenchyma. In addition, ex-

trahepatic criteria such as splenomegaly with infiltrative changes and lymphadenopathy may be seen.

Fig. 2.67 Lymphoma of the liver. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma with multiple hypoechoic masses and one almost completely anechoic lesion.

Infiltrating Lymphoma

Involvement of the liver is seen in about 50% of lymphoma cases (Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphoma). Particularly the more advanced stages will demonstrate hepatic involvement with circumscribed malignant lymphadenopathy. Diffuse, miliary, or periportal infiltration of the parenchyma is primarily found in early

stages of the disease and usually escapes ultrasound detection. In diffuse nonspecific parenchymal changes, the presence of splenic pathology and lymphadenopathy may warrant the presumed diagnosis of diffuse infiltrative lymphoma of the liver. This suspicion must then be confirmed by needle biopsy.

94

Metastases

Hypoechoic/anechoic malignant lesions or deposits within the liver are highly suspicious for a tumor with a high degree of malignancy and a low degree of differentiation (see below) (Fig. 2.68). Diffuse metastasis of the small nodular type may present as numerous anechoic masses that differ from polycystic liver disease by their irregular shape and diffuse margin. There is no posterior enhancement.

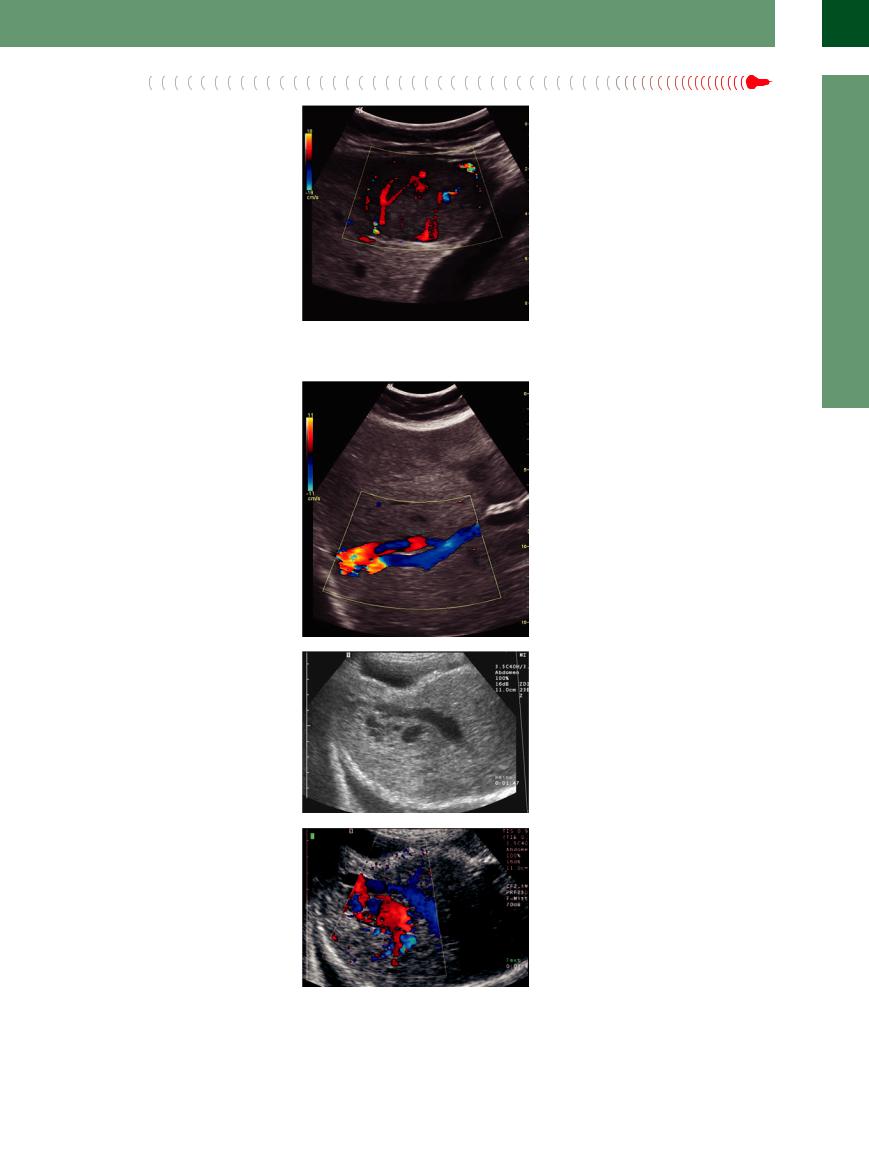

Fig. 2.68 Metastases of neuroendocrine tumors may present as almost anechoic lesions; in color Doppler sonography an intensive vascularity is detectable.

Vessels/Bile Ducts

Any differential diagnosis of anechoic masses in the liver has to include the possibility of vessels or bile ducts being viewed in crosssection. In this case, the characteristic aspects are the tubular shape of the lesion when imaged in a cross-section plane, and its course, which can be traced all the way back to the originating vessel/duct. In addition, vessels may be identified by duplex or color-flow duplex scanning as well as CEUS, which can differentiate between an enlarged bile duct or arterial, portal venous, and venous vessels. For reasons of clarity, these anechoic “masses” are listed here.

●Bile ducts. Bile ducts appearing as anechoic masses in the liver have to be pathologically enlarged/engorged (e. g., Caroli disease). These cases are characterized by their periportal location and identification of the socalled hepatic triad, i. e., delineation of a branch of each of the hepatic artery proper and the portal vein as well as the enlarged bile duct.

●Portal vein branches. Being part of the hepatic triad, the branches of the portal vein course through the periportal area as well. Venectasia, varicosities, and collaterals in case of portal hypertension will all be imaged as enlarged segments of the intrahepatic tree of the portal venous system.

●Hepatic vein branches. They are easily identified by their typical course terminating at their stellate junction with the vena cava. The sonographer should keep in mind the possible venectasia and anomalies of the Budd–Chiari syndrome.

●Hepatic artery aneurysms, shunts, and vascular malformation. These may be identified by color-flow duplex scanning and can be differentiated further by CEUS (Fig. 2.69).

Fig. 2.69a–c Demonstration of arteriovenous shunts.

a AV shunt in the right liver lobe in known hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler disease).

b AV malformation (Osler disease): spot-like anechoic masses, gray-scale image.

c Color Doppler sonography: vascular conglomerates.

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

95