- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

Papillary

Tree |

|

|

|

Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall |

Benign Periampullary Obstruction |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bile Duct Rarefaction |

|

Cancer |

|

|

|

|

||||

Biliary |

|

|

|

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Intrahepatic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hilar and Prepancreatic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intrapancreatic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Papillary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cholestasis |

|

|

Benign Periampullary Obstruction

Obstruction

The periampullary duodenal diverticulum is |

Vater is also quite rare. Sonography can hardly |

nal wall and intramural duodenal heterotopic |

very hard to visualize on ultrasound, and its |

ever demonstrate calculi impacted in the pap- |

pancreatic remnants, also escape sonographic |

role as a benign obstruction of the biliary tree |

illa of Vater. Other benign obstructions at the |

detection. |

remains unclear. True sclerosis of the papilla of |

level of the papilla, such as cysts of the duode- |

|

Cancer

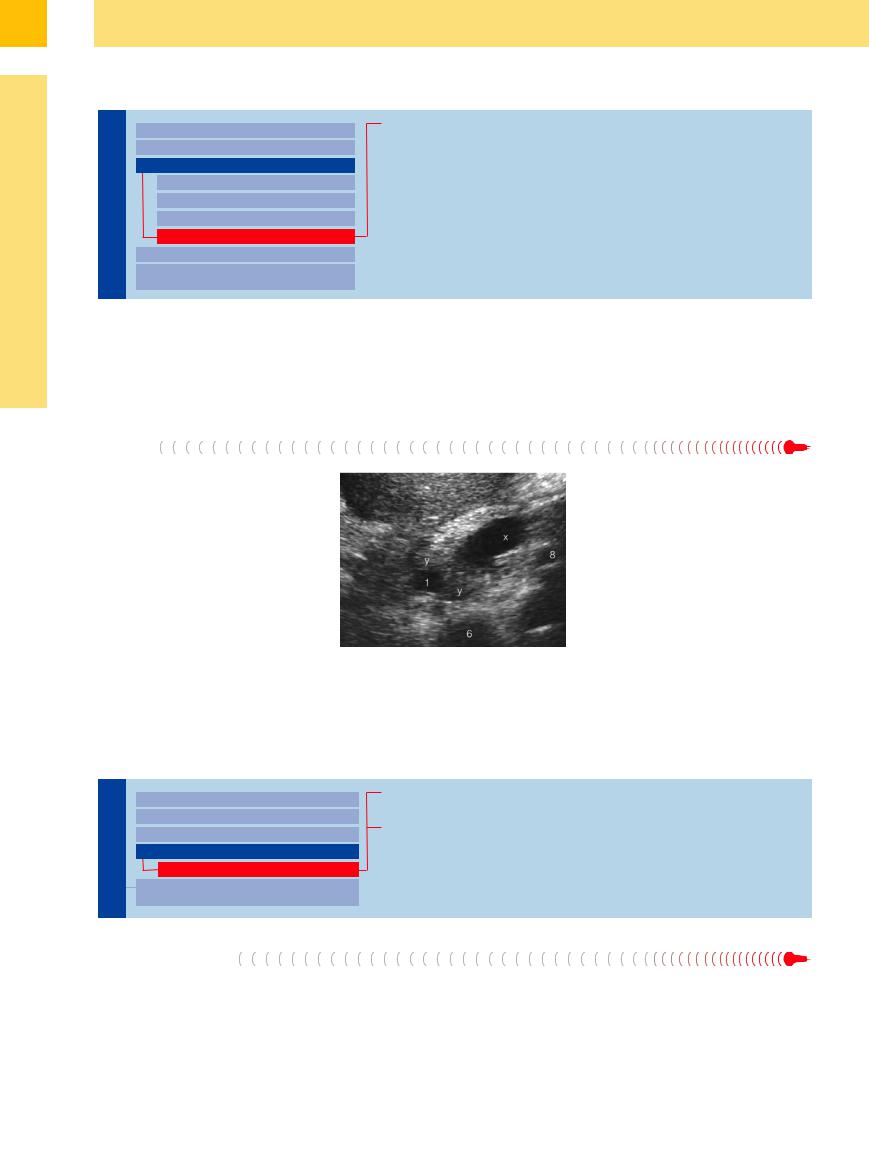

In characteristic sonomorphology, periampullary and true papillary carcinomas result not only in biliary but also pancreatic obstruction, with the “double duct dilatation” of both duct systems (Fig. 3.14, Fig. 3.26). In cases of painless jaundice, this sonographic picture raises the hope of possible curative surgery.

Fig. 3.26 Periampullary cancer (y) obstructing the CBD (1) and pancreatic duct (x); inferior vena cava (6), splenic vein (8).

■ Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

Foreign Body

Biliary Tree

Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

Bile Duct Rarefaction

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

Foreign Body

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic

Cholestasis

Pneumobilia/Stent

Uncommon Causes

Pneumobilia/Stent

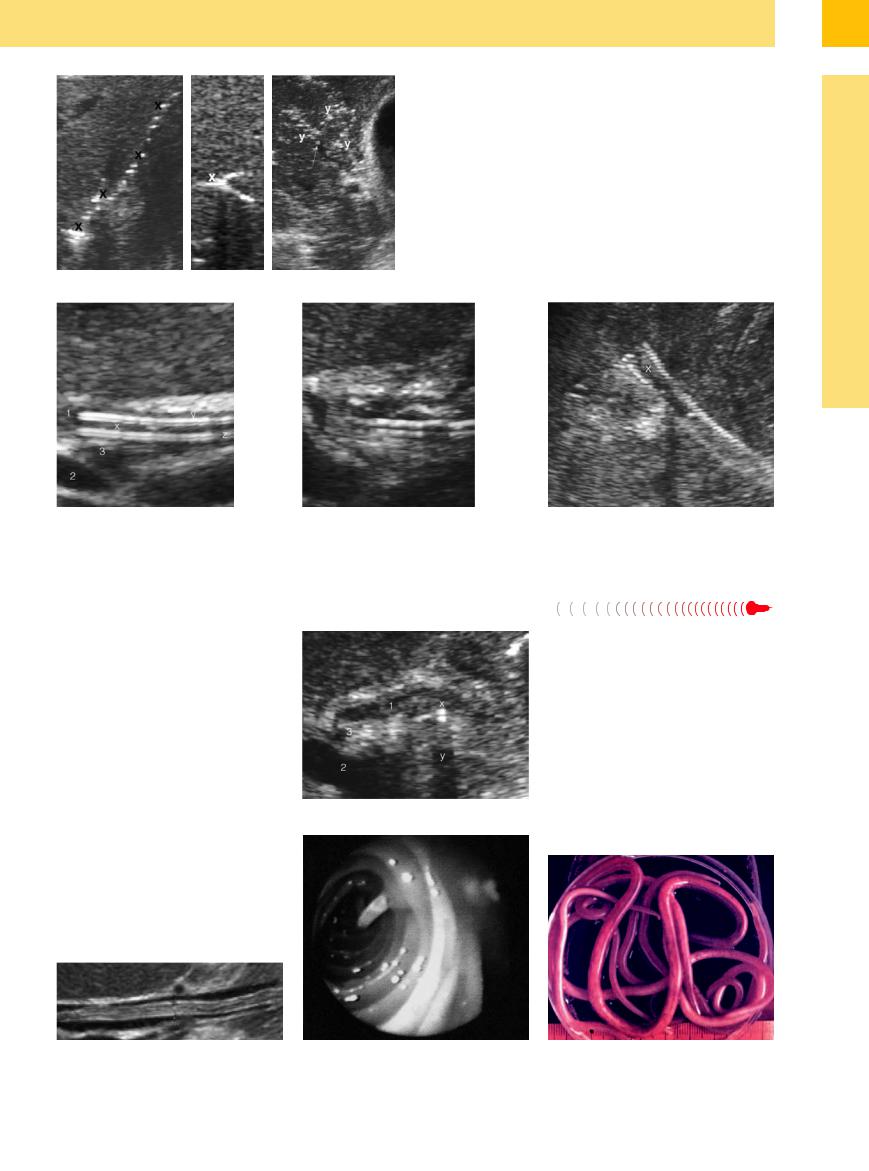

Intraductal gas or pneumobilia (Fig. 3.27) after endoscopic papillotomy (or hepatoenteric anastomosis) is a clear sign of unobstructed bile flow; here, too, sonography and endoscopy

of the abdomen are complementary rather than competing modalities. The same holds true when checking the function and position of biliary stents (Fig. 3.28). Unlike CT, sono-

graphic real-time scanning can easily differentiate between pneumobilia and the pulsatile snow-shower–like inflow of portal gas bubbles (Fig. 3.27).

140

Fig. 3.27 Pneumobilia (x) of the intrahepatic bile ducts, on the left in “string of beads” configuration and in the middle image filling a small duct completely. On the right: small and minute pulsatile inflow of brightly echogenic gas bubbles in the portal vein (y).

Fig. 3.28 Hepatoduodenal stents (x). |

b Dysfunctional stent with dilated CBD and sludge. |

a Satisfactory drainage. Anterior (y) and posterior walls |

|

(z) of the stent; portal vein (2). 1 = common duct; 3 = bile |

|

duct. |

|

Uncommon Causes

Numerous other intraluminal foreign bodies of the bile duct causing different degrees of biliary obstruction (including endoscopic data):

● Metal fragments after gunshot injuries (Fig. 3.24a)

● Nonabsorbable clips after surgery (Fig. 3.24b, Fig. 3.29a)

●Sutures and parts of T-tube drains

●Food particles (after extensive endoscopic papillotomy or after choledochoduodenostomy)

●Parasites (Echinococcus, Ascaris, Opisthorchis sinensis, and others) (Fig. 3.29b–d)

The sonographic morphology of these biliary obstructions, other than those due to Echinococcus, is nonspecific.

c Lumen (x) of a self-expanding hepatoduodenal stent with satisfactory drainage.

Fig. 3.29

a Clip (x), with posterior shadowing (y), close to the CBD after laparoscopic cholecystectomy; portal vein (2); hepatic artery (3); CBD (1) with residual inflammation of the wall (after endoscopic papillotomy).

3

Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

b Ascariasis of the CBD (image courtesy of Dr. Fayrz Sandouk, Damascus, Syria).

c ERC photograph: ascaris, emerging from the papilla of Vater.

d “Recovered” ascaris.

141

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

■ Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic Cholestasis

In today’s age of imaging modalities, the term cholestasis—meaning “stoppage of the bile flow”—is equated with mechanical obstruction of the bile flow. Thus, the differentiation of this term with respect to parenchymal cholestasis ( 3.3) in acute hepatitis (

3.3) in acute hepatitis ( 3.3a), hepatic congestion (

3.3a), hepatic congestion ( 3.3b), portal vein thrombosis

3.3b), portal vein thrombosis

( |

3.3c), cholangitis with abscess formation |

( |

3.3 d), diffuse metastasis ( 3.3e), or in |

cirrhosis ( 3.3f–h) has become an issue of minor importance. This is understandable because the extent and duration of the ductal distension, and the type and anatomical location of the obstruction with its possible impact on bile flow dynamics, can be visualized so easily by means of ultrasonography.

3.3f–h) has become an issue of minor importance. This is understandable because the extent and duration of the ductal distension, and the type and anatomical location of the obstruction with its possible impact on bile flow dynamics, can be visualized so easily by means of ultrasonography.

As in all other fluid-filled tubular systems, any pressure increase in the bile-filled vessels

will increase their diameter, pressure in the adjacent tissue permitting, and thus result in distension. Therefore, the leading differential diagnostic sign in the sonographic morphology of cholestasis is distension of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts, with or without clinical symptoms and rarely without concomitant rise in the blood level of bilirubin and/or the other enzymes characteristic of cholestasis.

The Seven Most Important Questions

Biliary Tree

Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

Bile Duct Rarefaction

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic

Cholestasis

The Seven Most Important Questions

Relationship with the Biliary Tree Pressure Increase

Bile Duct Diameter Level of Flow Obstruction Possible Malignancy Duration of Obstruction

Thickness of Bile Duct Wall

1. Are the vascular structures in question truly part of the biliary tree? The first step in the differential diagnosis of vascular distension within the liver parenchyma or at the porta hepatis is to ascertain whether the vessels are truly part of the biliary tree. Intrahepatic arteries or the arteries and veins of the porta hepatis are typical examples of such misdiagnosed structures ( 3.3f,i,j). Even without the capabilities of color-coded Doppler scanning of the flow, precise knowledge of the anatomy with its numerous variants is essential for this first step in the differential diagnosis.

3.3f,i,j). Even without the capabilities of color-coded Doppler scanning of the flow, precise knowledge of the anatomy with its numerous variants is essential for this first step in the differential diagnosis.

2. Are there signs of a (segmental or general) pressure increase in the biliary tree? The second aspect to be addressed when considering dilatation of the biliary tree is to resolve the issue of a pressure-independent increase in the diameter (“ectasia”) ( 3.4 d) or true dilatation by increased tubular pressure (

3.4 d) or true dilatation by increased tubular pressure ( 3.4- e–h)—either within individual segments (“levels”) (

3.4- e–h)—either within individual segments (“levels”) ( 3.4i–k,n,v) or the entire biliary tree (

3.4i–k,n,v) or the entire biliary tree ( 3.4 l–u, w–z). Congenital malformations such as choledochal cysts or Caroli disease and the age-dependent increase in the ductal diameter, particularly that of the prepancreatic CBD, are not pressure-dependent (

3.4 l–u, w–z). Congenital malformations such as choledochal cysts or Caroli disease and the age-dependent increase in the ductal diameter, particularly that of the prepancreatic CBD, are not pressure-dependent ( 3.4 d). The prevailing concept that the diameter of the common duct increases after cholecystectomy does not hold true.

3.4 d). The prevailing concept that the diameter of the common duct increases after cholecystectomy does not hold true.

3. What is the diameter of the bile ducts—ob- served and measured? The third question deals with the determination of the bile duct diameter. Values measured in millimeters at ill-

defined locations are diagnostically inferior to the morphological appearance of the biliary tree, since the latter allows much better conclusions to be drawn regarding the actual cause of the increased pressure within the bile ducts ( 3.4 d–h). Vessels distended owing to increased pressure are more or less dilated along their entire prestenotic course; it should be noted that in case of extrahepatic obstruction the hepatic duct confluence is easily differentiated from its surroundings. Only ectatic segments of the bile tree (preferably in the prepancreatic region of the CBD) with slender segments upstream (

3.4 d–h). Vessels distended owing to increased pressure are more or less dilated along their entire prestenotic course; it should be noted that in case of extrahepatic obstruction the hepatic duct confluence is easily differentiated from its surroundings. Only ectatic segments of the bile tree (preferably in the prepancreatic region of the CBD) with slender segments upstream ( 3.4 d) do not exhibit any intraductal pressure increase, i. e., no cholestasis.

3.4 d) do not exhibit any intraductal pressure increase, i. e., no cholestasis.

It stands to reason that in cases of intraductal pressure increases the possibility of ductal dilatation depends on the pressure of the surrounding tissue: for instance, if the intrapancreatic course of the CBD becomes visible this is (almost) proof of a significant pressure increase in the prepapillary segment which must more than negate the compression exerted by the head of the pancreas. Cirrhosis of the liver will not result in dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary tree even if the pressure increases significantly.

4.At what level of the biliary tree is the obstruction located?

5.Is the obstruction malignant or benign? The fourth question concerning the “level” and the fifth question dealing with the nature (malignant or benign) of the biliary obstruction are

discussed in detail elsewhere in this chapter, in the section on “Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure.”

6. How long has the biliary tree been obstructed/dilated (acute—hours/days, or chron- ic—weeks/months)? The sixth issue focuses on the duration of the cholestasis and has to be resolved in the context of the patient’s history and laboratory work-up. Lacking any muscle layers, the walls of the bile ducts are quite thin, and therefore any pressure increase will result in immediate expansion of their diameter. In acute obstruction from calculi, e. g., impacted in the papilla of Vater, bile duct dilatation is the first detectable symptom ( 3.4h) and can be demonstrated several hours before any rise in the cholestatic enzymes.

3.4h) and can be demonstrated several hours before any rise in the cholestatic enzymes.

Compensated chronic (weeks or months) obstruction in the intrahepatic or extrahepatic segments of the biliary tree ( 3.4f,h,j,l,u–z) can lead to bizarre bile duct dilatation (

3.4f,h,j,l,u–z) can lead to bizarre bile duct dilatation ( 3.4x) and tortuosity.

3.4x) and tortuosity.

7. Is there localized or diffuse thickening of the bile duct walls? The seventh aspect to be considered in the differential diagnosis of cholestasis concerns the thickness of the bile duct walls. If the obstructed bile flow is accompanied by cholangitis, quite often thickening and layering can be demonstrated in the bile duct walls, in particular after successful relief by interventional endoscopy. Irregular wall thickening, with juxtaposed segmental narrowing and dilatation of the bile ducts, is characteristic of PSC (Fig. 3.6).

142

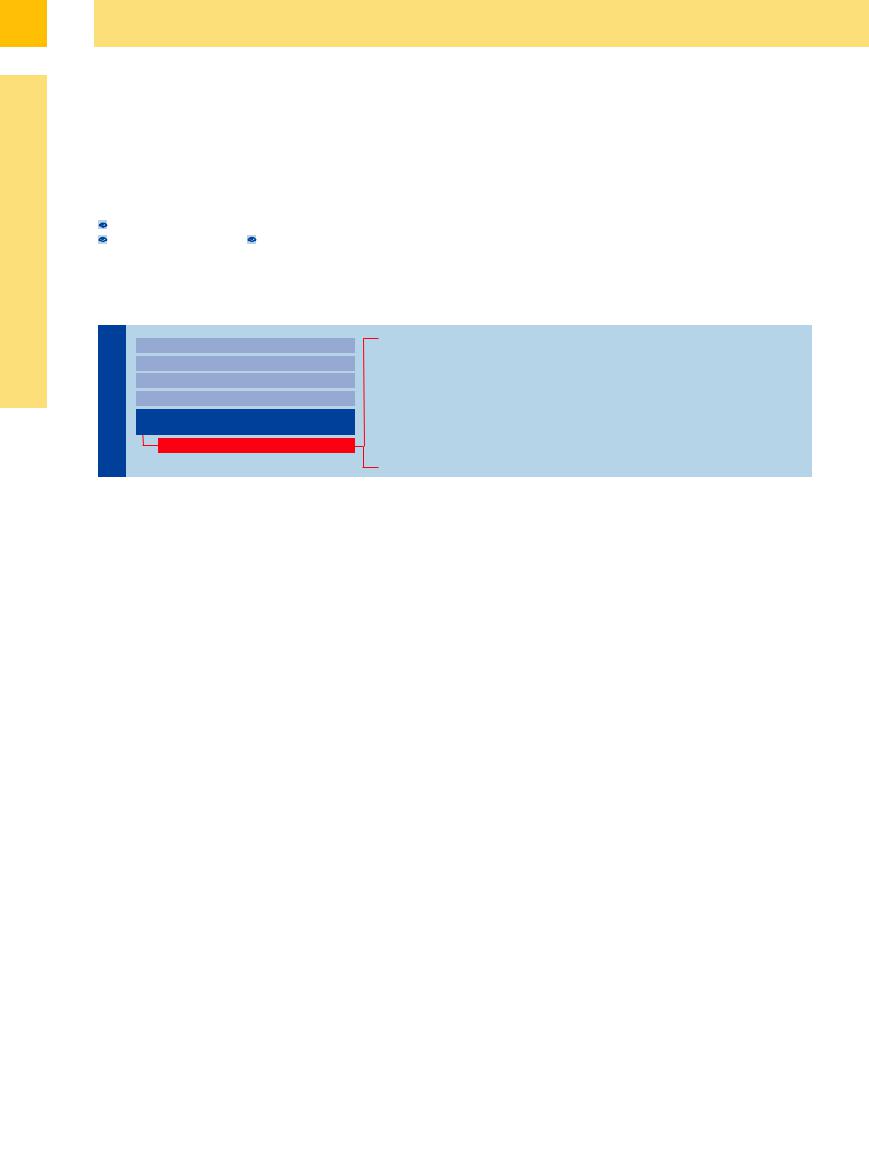

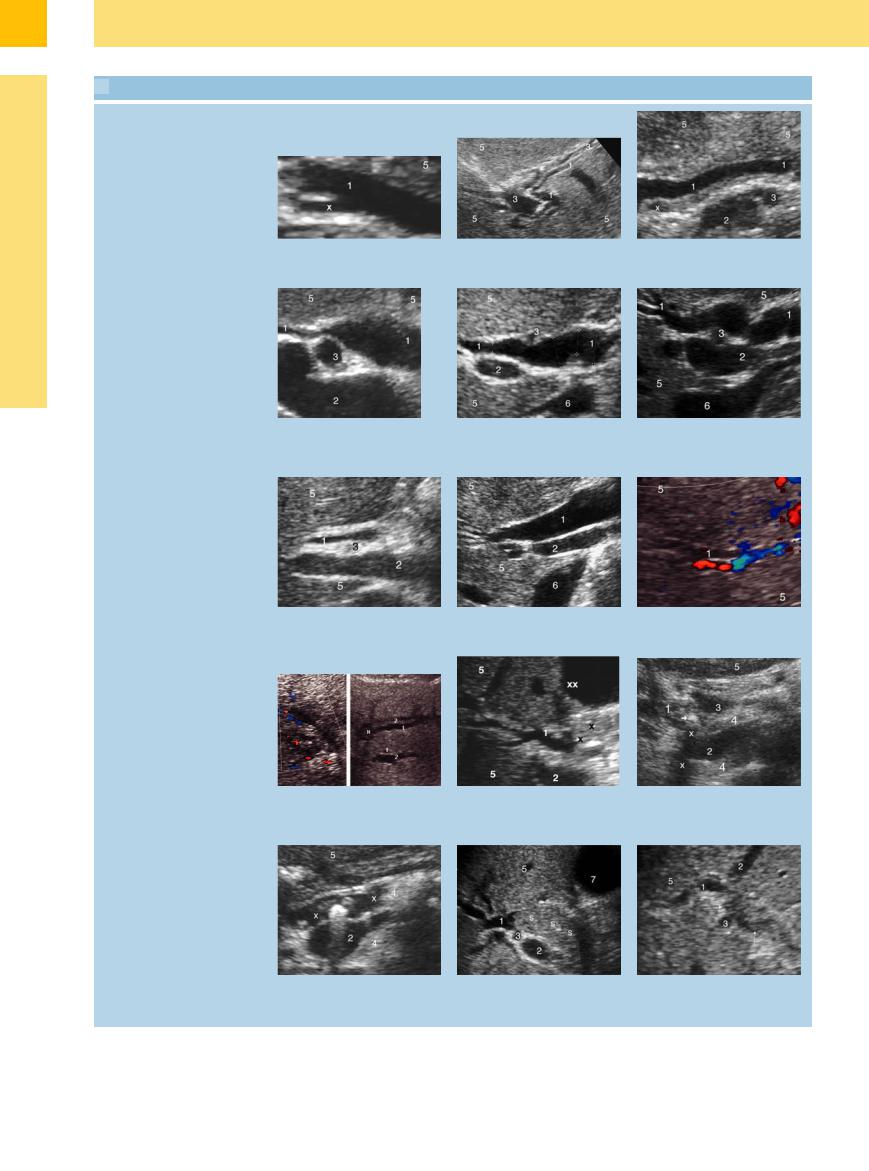

3.3 Parenchymatous Cholestasis

3.3 Parenchymatous Cholestasis

Viral hepatitis, congested liver, portal vein thrombosis

a Gallbladder, with a lot of sludge but little fluid and ill-defined wall (7), in acute hepatitis A. 2 = branch of the portal vein; 5 = liver.

Abscess, metastases

d Cholangitis with intrahepatic (5) abscess

(a). 2 = branch of the portal vein; 6 = hepatic vein.

Cirrhosis

g Portal hypertension with convoluted varicosities (x) in the wall and lumen of the gallbladder (7).

Differential diagnosis of fluid-filled structures

i Portal vein (2); variant course of the hepatic artery (3). 6 = inferior vena cava.

b Congested liver (5). Left: With dilated inferior vena cava (6), and congested middle (xx) and right (xxx) hepatic vein. Right: Same constellation, plus gas-filled parts of the lung (y).

e Diffuse liver (5) metastases (x).

h Segment I vein (x) of the caudate lobe

(5). 6 = inferior vena cava.

c Left: Thrombosis of the portal vein (2); hepatic artery

(3). Right: Thrombosis of the intrahepatic portal veins (2) with concomitant dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts

(3).

f Left: Macronodular (x) cirrhosis of the liver (5). Right: Rather pronounced hepatic artery (3) in known cirrhosis. 2 = portal vein.

j B-mode image and color-coded visualization of the cavernous transformation of the portal vein (2).

Practical Considerations |

|

The differential diagnosis of “sonographic |

interventional/therapeutic partners, pref- |

cholestasis”—more precisely, the question |

erably performed by the same physician. |

of obstructive nonparenchymatous choles- |

Other diagnostic modalities such as CT or |

tasis—is the prime example of a medical |

MRI would usually not be needed at all. |

problem where ultrasonography and endos- |

|

copy are the perfect diagnostic as well as |

|

3

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic Cholestasis

143

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

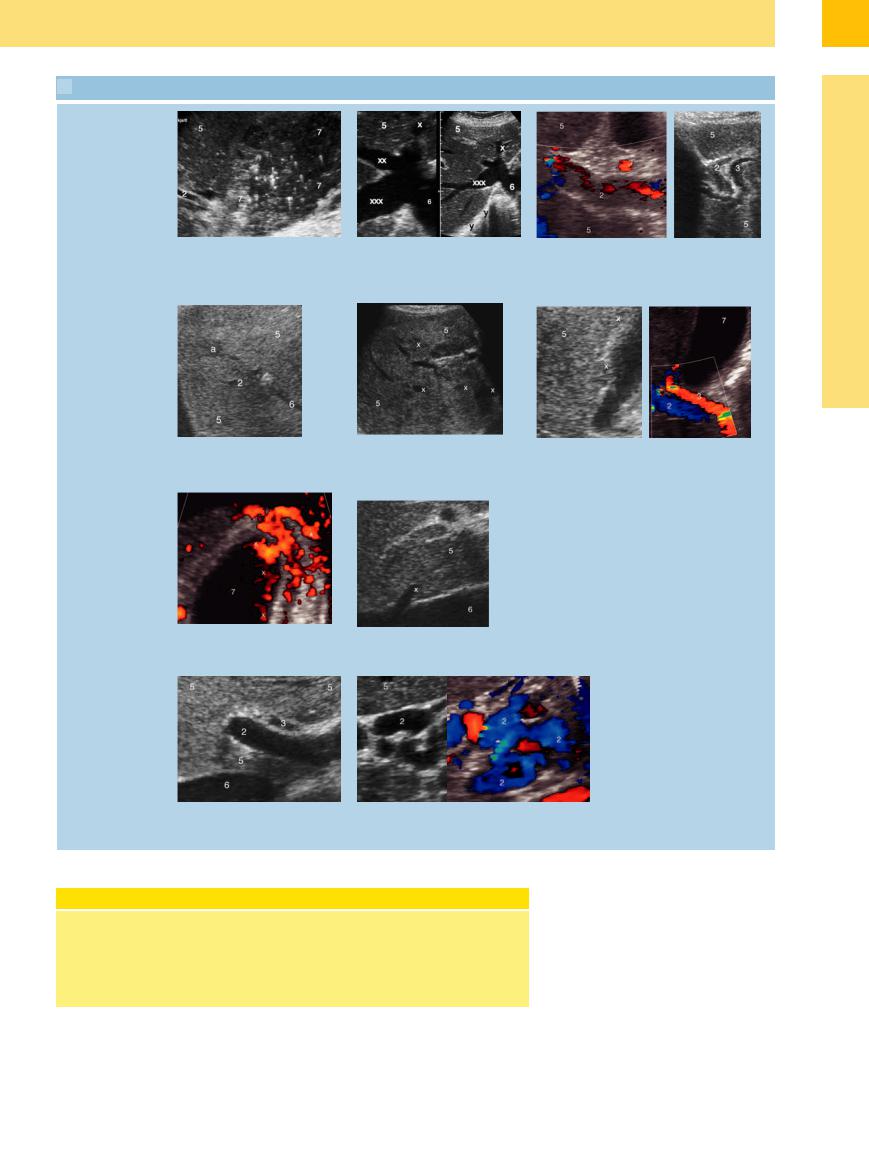

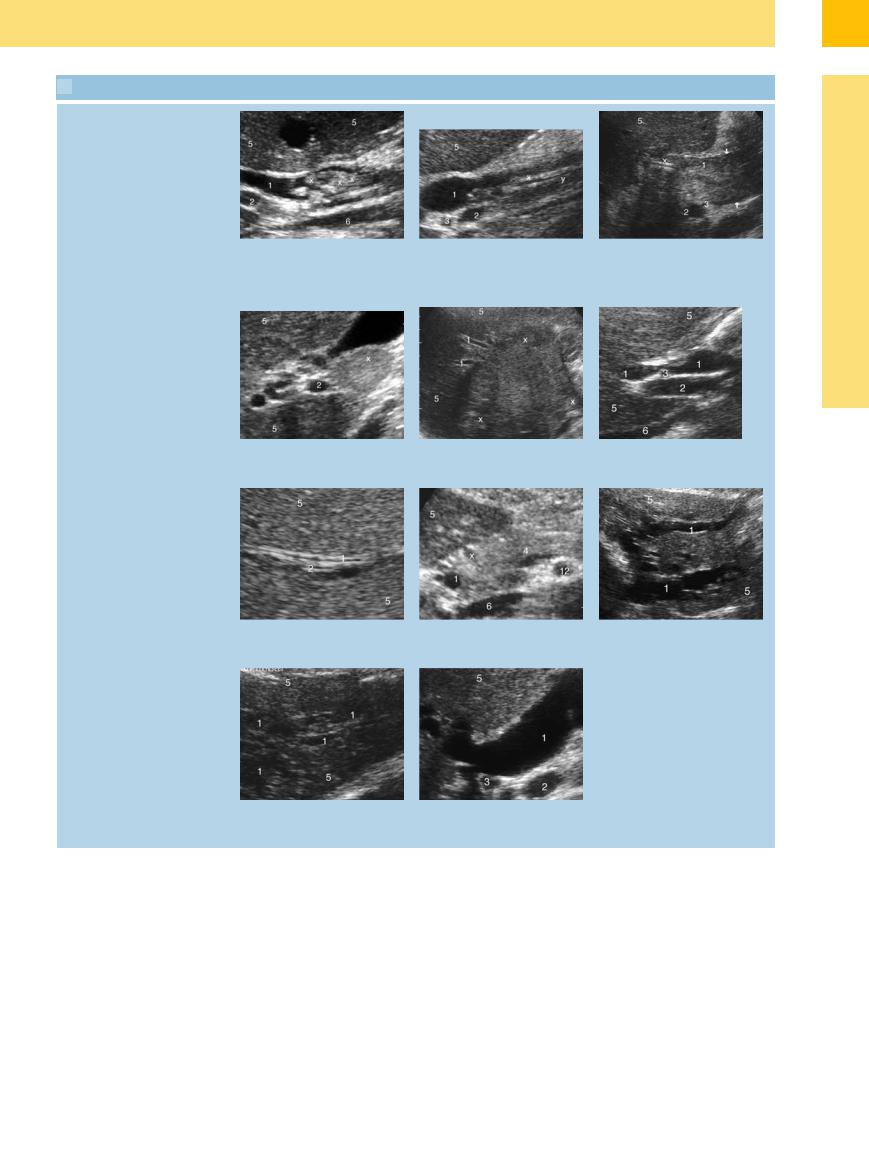

3.4 The Diagnosis of “Sonographic Cholestasis”

3.4 The Diagnosis of “Sonographic Cholestasis”

Bile duct dilatation: shape, location, degree, origin. Pancreas (4), liver (5), inferior vena cava (6), gallbladder (7)

Bile duct dilatation: shape, location, degree, origin. Pancreas (4), liver (5), inferior vena cava (6), gallbladder (7)

a Dilated CBD (1) with distended cystic duct (x).

d Cholangiectasia with slender CBD (1) upstream and prepancreatic distension. 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery.

g Acutely congested CBD (1) (erroneously normal diameter on measurement). 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery.

j Dilated intrahepatic bile ducts (1). Left: In CCC (confirmed by needle aspiration biopsy). Right: Adjacent branches of the portal vein (2) in CCC (x).

m Intensively reflecting stone in the dilated pancreatic duct (x). 2 = venous confluens with splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein.

b Characteristic “double-barreled shotgun” sign with intrahepatic branches of the bile ducts (1) and portal veins (3).

e Subjective morphological dilatation of the CBD (1) with various possible errors in measurement. 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery (variant position).

h Significantly (chronic) dilated intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree (1). 2 = portal vein.

k Dilated intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree (1) in stenosis (x) due to tumor (CCC?). 2 = portal vein; xx = liver cysts.

n Dilated intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts (1) due to sludge (s) after ESWL of a CBD gallstone. 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery.

c Dilated prepancreatic CBD (1) with small (inflammatory?) lymph node (x). 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery.

f Dilated CBD (1) after biliary colic exceeding the limits. 2 = portal vein, 3 = hepatic artery.

i Dilated intrahepatic bile duct (1).

l Small stone (arrow), shadowing (x) in the CBD (1). 2 = venous confluens; 3 = hepatic artery.

o Obstruction of the main right (1) and left (2) bile ducts (→) due to tumor, probably CCC. 3 = hepatic artery.

144

3.4 The Diagnosis of “Sonographic Cholestasis” (Continued)

3.4 The Diagnosis of “Sonographic Cholestasis” (Continued)

p Dilated CBD (1) due to fragmentation (x) of an intraductal calculus by ESWL. 2 = portal vein.

s Lymphadenophathy (x) probably inflammatory in autoimmune hepatitis. 2 = portal vein.

v Moderate “double-barreled shotgun” sign with dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (1). 2 = branches of the portal vein.

y Maximum dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary tree (1) with almost lacunar transformation.

q Dilated CBD (1) due to nonfunctional stent; “anterior” (x) and “posterior” (y) wall of the stent. 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery.

t Dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts (1) in a large CCC (x).

w Dilated intrahepatic CBD (1). 12 = superior mesenteric artery; x = gastroduodenal artery.

z Maximum (long-term chronic) dilatation of the CBD (1). 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery.

r Well-differentiated cholangiocarcinoma (initially biliary papillomatosis) with pronounced dilatation of the CBD (→ ←). 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery; x = biliary stent.

u Slightly dilated CBD (1). 2 = portal vein; 3 = hepatic artery.

x Significant (chronic) dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (1).

3

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic Cholestasis

145