- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

11

Urinary Tract

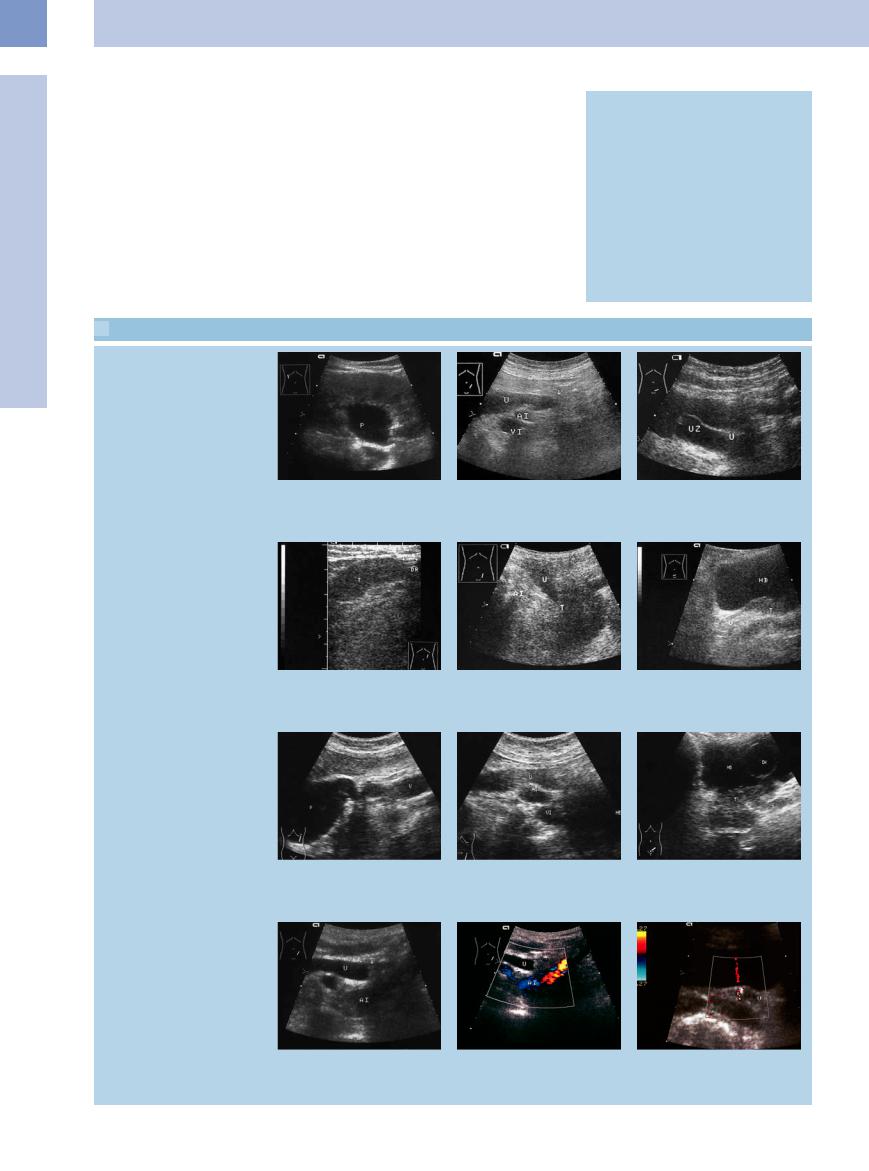

Fig. 11.14 Megaureter (U).

a Primary obstructive megaureter (U), caused by a perivesical fibrotic stenosis (arrow).

b Massive cystic dilatation of the complete ureter and pelvis with prevesical massive dilatation. As a differential diagnosis, a high-grade nonobstructive non-reflexive megaureter should be considered; there is no certain evidence of a juxtavesicular stenosis. HBL = bladder.

■ Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

Anechoic

Urinary Tract

Malformations

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter  Anechoic

Anechoic

Hypoechoic

Renal Pelvic Mass, Ureteral Mass Changes in Bladder Size or Shape Intracavitary Mass

Wall Changes

Pyelectasis

Subpelvic Ureteral Stenosis

Urinary Stone Colic

Chronic Urinary Stasis

Retroperitoneal Fibrosis (Ormond Disease)

Reflux

Pyelectasis

Pyelectasis refers to an anechoic separation of the central renal sinus echogenicity due to dilatation of the renal pelvis with no associated expansion of the caliceal system or upper ureter. Pyelectasis may result from an ampullary renal pelvis or from fluid diuresis (Fig.11.15, Fig.11.16).

Other frequent causes are incipient urinary stasis, such as that resulting from pregnancy or stone colic with an incomplete obstruction, as well as urinary retention (Figs. 11.17, 11.18, 11.19).

The differential diagnosis should include all conditions that cause a hypoechoic, dilated re-

nal pelvis (see below) as well as anechoic or hypoechoic transformation of the sinus echo (Fig.11.20).

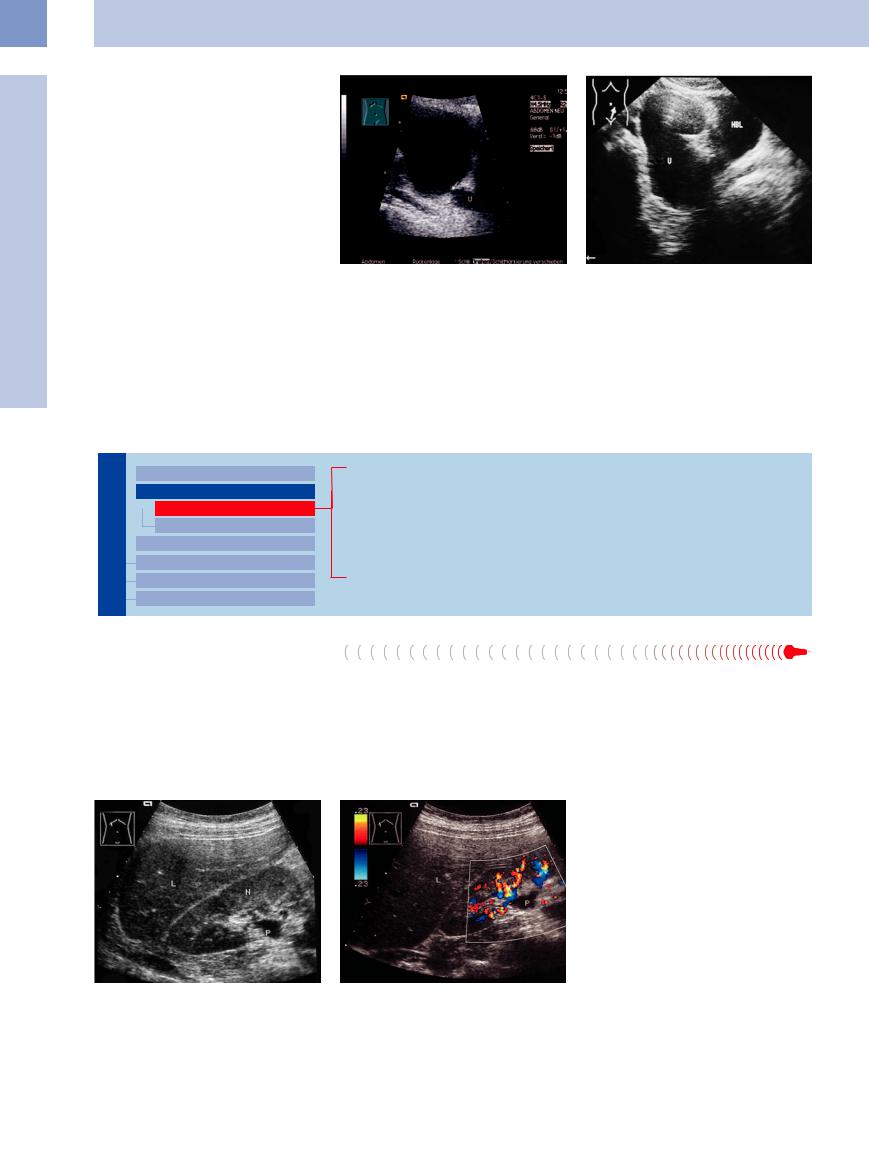

Fig. 11.15 Pyelectasis (P). L = liver; N = kidney.

a B-mode image: typical triangular, echo-free mass in the sinus echo complex with nonvisualization of the proximal ureter.

b Color Doppler image: a dilated renal vein can be excluded from the differential diagnosis (see also

Fig. 11.20).

386

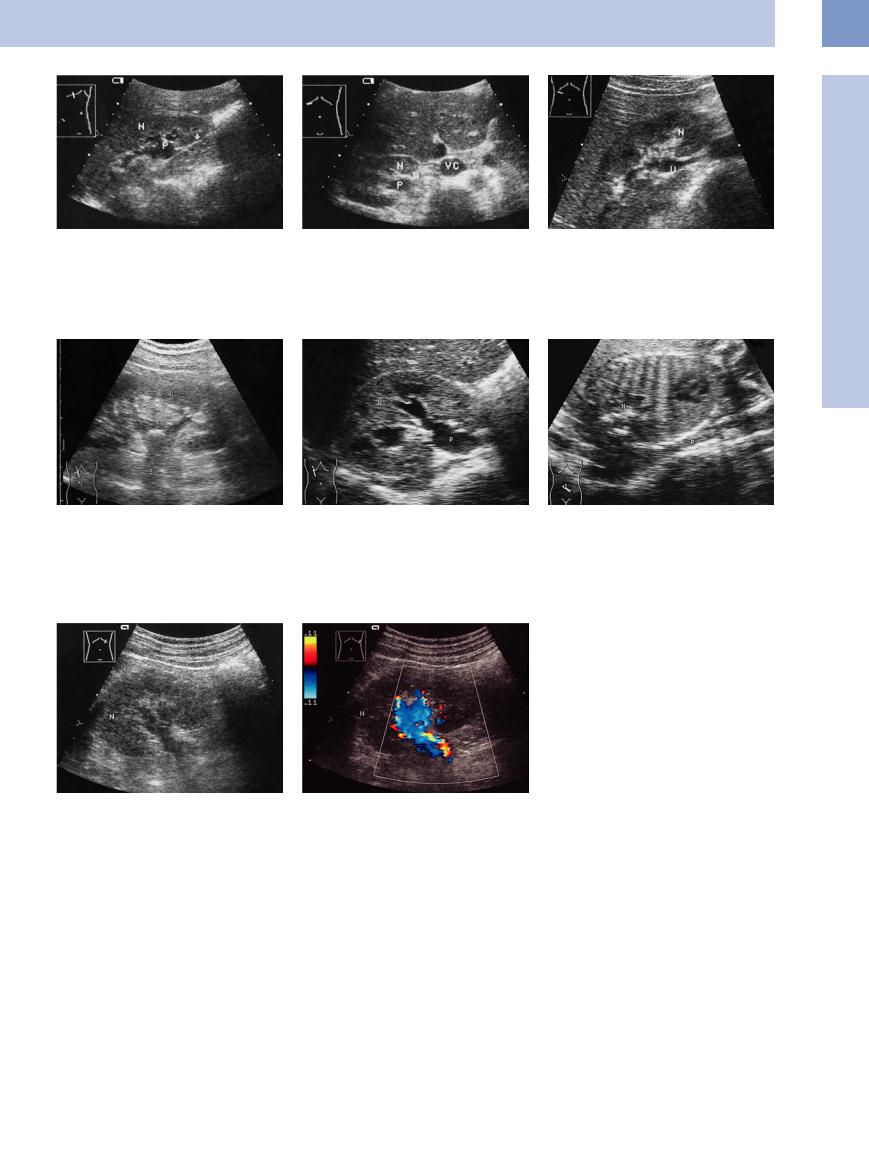

Fig. 11.16 Pyelectasis resulting from an ampullary renal pelvis. L = liver; N = kidney.

aEnlarged, anechoic pyelocaliceal system (P), scan from

amore lateral angle shows a nondilated, normal-appear- ing ureter (arrow).

Fig. 11.18 Renal pelvic stone (arrow, acoustic shadow S) with radial anechoic streaks representing the dilated calices and infundibula. Here the renal pelvis is only minimally dilated. These stones are often missed at ultrasound, as are stones at the ureteropelvic junction (see also Fig. 11.22). N = kidney.

b High transverse scan of the right kidney (N). Posterior to the artery is the ectatic renal pelvis (P) with no dilatation of the proximal ureter. VC = inferior vena cava.

Fig. 11.19

a Obstructive pyelectasis. N = kidney; P = pelvis.

Subpelvic Ureteral Stenosis

Stenosis

A dilated pyelocaliceal system with no ureteral |

is not associated with progressive dilatation, |

dilatation indicates a subpelvic stenosis. |

and so there is no functional deterioration |

Primary causes are congenital aberrant ves- |

over time. Progressive stenoses culminate in |

sels and congenital ureteropelvic junction ob- |

a hydronephrotic, nonfunctioning kidney |

struction due to fibrous bands (see above). |

(Fig.11.12). |

Most cases involve a partial obstruction that |

|

Fig. 11.17 Pyelectasis with a dilated proximal ureter (U). Obstruction? The patient presented clinically with suppurative pyelitis. IVP (IV urogram) showed an ampullary renal pelvis with no outflow obstruction. N = kidney.

b Cause: pregnancy.

Fig. 11.20 Initial sonographic impression: obstructive pyelectasis of the left kidney (N).

a B-mode image shows an echo-free band in the sinus echo complex.

b Color Doppler: a dilated renal vein.

The differential diagnosis includes secondary stenoses due to postoperative stricture, stone obstruction, or urothelial carcinoma (Figs.11.13, 11.21, 11.22, 11.23).

11

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

387

11

Urinary Tract

Fig. 11.21 Subpelvic ureteral stenosis. Cause: postopera- |

Fig. 11.22 Stone (cursors, acoustic shadow S) obstructing |

tive ligation/clip (arrow). Dilated upper ureter (U; |

the upper ureter (U). |

N = kidney). |

|

Urinary Stone Colic

Continuing urinary stasis lasting hours or days constitutes an acute stasis, whereas a chronic stasis continues for month or years. Urinary stasis can be total or partial.

When the obstructing stone is not located at the ureteropelvic junction, ultrasound shows the features of pyelocaliectasis and ureteral dilatation. Stones tend to become impacted at three sites of physiological narrowing (Fig.11.3,

Fig.11.5):

●The ureteropelvic junction

●The point where the ureter crosses the iliac vessels

●The ureterovesical junction

Generally the ureter is not visualized by ultrasound unless it is filled with fluid as the result of an obstruction. It then appears as an anechoic band that can be traced distally from the renal pelvis, in some cases as far as its insertion in the bladder floor (Fig.11.3). Usually the impacted stone can be detected and local-

ized. This is not possible with partial obstructions, but in these cases it may be possible (with effort) to locate a constant, hyperechoic stony structure that casts an acoustic shadow.

Urinary stasis is present when:

●there is an anechoic dilatation of the renal pelvis of more than 2(–4) cm, measured in a transverse scan direction

●the neck of the calix is enlarged to more than 4 mm, and

●the ureter is enlarged to more than 5 mm.

Stasis is also indicated by

●a unilateral decrease or absence of the ureteral jet phenomenon (3–4 per minute is normal), and

●an elevated resistance index (RI): in the interlobar arteries RI exceeds 0.7 in the case of complete obstruction.

Sensitivity for stone detection in ultrasound is up to 81%, in CT 92–96%. Clinical examination

Fig. 11.23 Two small masses with cyst-like ultrasound features in the lower moiety of a duplex kidney. Dilated pyelocaliceal system. Cause: urothelial carcinoma at the ureteropelvic junction ( 11.2 d).

11.2 d).

Clinical Note

If a stone is detected and infection is not present, several days of conservative therapy may be tried under ultrasound surveillance before proceeding with invasive treatment. Intravenous urography is contraindicated, as the contrast administration could lead to rupture of the fornix or ureter (Fig. 11.27). If the ultrasound findings are equivocal, an abdominal plain film can be taken to check for a shadowing calculus.

and sonography together (including the “twinkling artifact”) result in a sensitivity of 98% (Figs. 11.24, 11.25, 11.26, 11.27; see also Figs. 11.49, 11.50, 11.51, 11.52).3

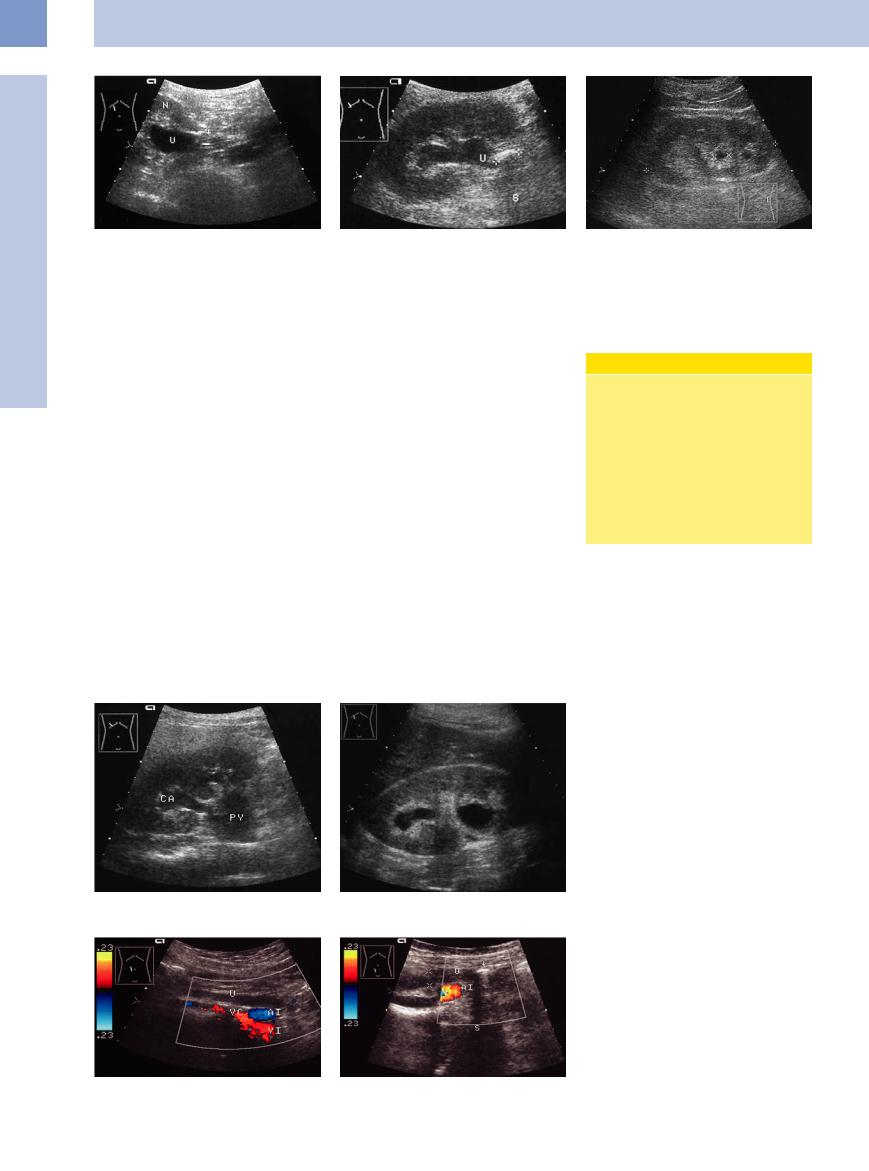

Fig. 11.24 Dilated pyelocaliceal system in a patient with flank pain. Suspicion of biliary colic.

a Dilated calix (CA) communicating with the dilated and obstructed renal pelvis (PY).

b A proximal ureteral stone (arrow) causing obstructive caliceal ectasia. Scan shows two echo-free masses in the central echo complex. The upper mass represents an ectatic caliceal neck. The enlargement of a caliceal neck to more than 5 mm (here 11 mm) indicates obstruction. The lower mass is the dilated renal pelvis.

Fig. 11.25 Color Doppler examination.

a Course of the ureter (U) anterior to the vena cava (VC) and the iliac artery and vein (AI; VI), oblique scan through the right midabdomen.

b Lower part of the ureter (U) in the lesser pelvis, anterior to the iliac artery (AI). The impacted stone (arrow, acoustic shadow S) is visualized.

388

Fig. 11.26a and b Renal and ureteral obstruction. |

b Cause: prevesical stone with an acoustic shadow (S); |

Fig. 11.27 Fluid collection around the lower pole of the |

a Pyelocaliceal stone (arrow, acoustic shadow S), dilated |

2 days later, detectable urine flow (ureteral jets). HB = |

kidney: urinoma (arrows). Dilatation of the renal pelvis (P) |

renal pelvis (P). N = kidney. |

bladder; U = ureter. |

and ureter (U). |

Chronic Urinary Stasis

Ureteral function. Urinary transport occurs actively through the muscle layer. In obstruction the pressure is increased to around 5–10 times the normal value. Ureteral pressure runs parallel to tubular pressure and glomerular function, and the glomerular filtration rate falls as the ureteral pressure rises. Therefore in chronic

obstruction, there is a reduction and an elimination of function.

Chronic urinary stasis is based on a disturbance of urinary transport. Urinary stasis can be classified into four grades of severity, as described by Gladisch,4 based on its sonographic appearance. This assessment includes evaluat-

11.1 Sonographic Criteria for Grading the Severity of Urinary Stasis

11.1 Sonographic Criteria for Grading the Severity of Urinary Stasis

Mild urinary stasis (grade I) |

● Pyelocaliectasis with anechoic separa- |

|

tion of the renal sinus echo complex; |

|

the ureter or ureteropelvic junction |

|

may be dilated and echo-free |

|

● Preservation of the bright sinus |

|

echoes |

|

● Normal thickness of the renal paren- |

|

chyma |

Moderate urinary stasis (grade II) |

● Marked caliceal dilatation to |

|

5–10 mm, pyelectasis |

|

● Ureteral dilatation, incipient tortuosity |

|

● Parenchyma still normal or slightly |

|

thinned |

|

● Diminished sinus echo complex |

Severe urinary stasis (grade III) |

● |

Massive caliceal dilatation, pro- |

|

|

nounced anechoic pyelectasis |

|

● Intensive anechoic dilatation of the |

|

|

|

pyelocaliceal system |

|

● Loss of the sinus echo complex |

|

|

● |

Rarefaction of the renal parenchyma |

Hydronephrotic sac (grade IV) |

● Anechoic cystic mass in the central |

|

echo complex due to severe pyeloca- |

|

liceal dilatation |

|

● Complete loss of the renal sinus |

|

echogenicity |

|

● Complete or almost complete loss of |

|

the renal parenchyma |

ing the degree of renal pelvic distension by fluid, the integrity of the renal sinus echo complex, and the loss of renal parenchyma ( 11.1).

11.1).

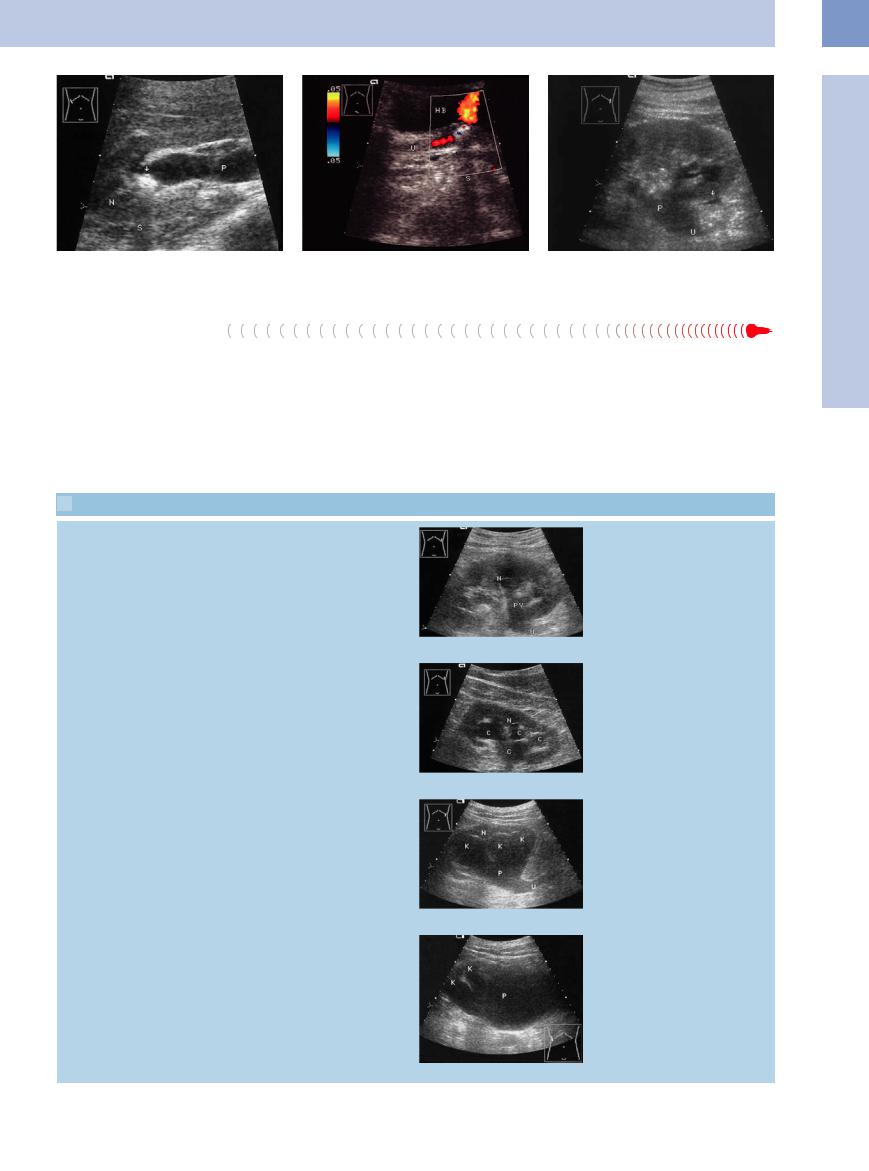

Chronic urinary stasis can have a variety of causes, most of which can be demonstrated with ultrasound. Once urinary stasis has been detected sonographically, the cause can often

a Echo-free separation of the central renal sinus echogenicity; preservation of sinus echoes; intact parenchyma (N). This patient had metastatic colon cancer and postoperative ureteral occlusion by a suture ( 11.2f). PY = pelvis; U = ureter.

11.2f). PY = pelvis; U = ureter.

b Conspicuous, echo-free pyelocaliectasis

(C) with diminished sinus echoes and incipient parenchymal thinning. Postoperative ureteral occlusion by a suture as above, 6 months later. N = kidney.

c Conspicuous, echo-free pyelocaliectasis (K, P); loss of renal sinus echogenicity; thinned parenchyma, dilated ureter (U). Patient had a metastatic ovarian tumor. N= kidney.

d Calices (K) and renal pelvis (P) are combined to form an echo-free hydronephrotic sac with little or no evidence of any residual parenchyma.

11

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

389

11

Urinary Tract

be discovered by starting with a posterolateral scan of the ureteropelvic junction and then moving the scan anterolaterally and inferomedially, using color Doppler as needed, until the dilated, anechoic ureter appears to terminate. This site marks the point of the obstruction.

A special form of urinary stasis due to outflow obstruction is hydronephrosis. It is identical to the grade IV hydronephrotic sac described above, but there are several special features in addition to chronic urinary stasis:

the condition is usually detected incidentally and is based on an unnoticed, often congenital, cause. Its significance lies in the fact that when it is bilateral (usually due to an infravesical cause), it can lead to end-stage renal failure, infection, and pyonephrosis (see below).

The various causes of chronic urinary stasis are listed in Table 11.1 and illustrated in 11.2.

11.2.

11.2 Causes of Chronic Urinary Stasis

11.2 Causes of Chronic Urinary Stasis

Ureteropelvic junction stone, ureteral stricture, ureterocele

Table 11.1 Causes of chronic urinary stasis

●Ureteropelvic junction obstruction, aberrant vessel

●Impacted stone

●Clot or necrotic papilla

●Stricture (congenital, postoperative, tuberculosis)

●Ectopic ureteral insertion, ureterocele

●Bladder tumor

●Prostatic hypertrophy or tumor

●Colon carcinoma

●Ovarian carcinoma

●Ureteral carcinoma

●Ormond disease

a Ureteropelvic junction obstruction? (arrow; no dilated ureter), dilated renal pelvis (P); B-mode image.

b Postoperative ureteral stricture (U, arrows): indistinct ureter in a hypoechoic scarred area. AI = iliac artery; VI = iliac vein.

c Ureterocele (UZ) with an obstructed ureter (U).

Ureteral tumor obstruction

d Ureteral tumor (urothelial carcinoma, T): hypoechoic oval mass with smooth margins; indwelling drain (arrows, DR).

g–i Grade II urinary stasis caused by a bladder tumor.

g Ureteropelvic junction. P = pelvis; U = ureter.

e Locoregional metastasis of ovarian carcinoma (T): cuto of the obstructed ureter (U) at the level where it crosses the iliac vessels (AI).

h Ureteral tortuosity over the iliac artery and vein (AI, VI).

f Metastatic prostate cancer (T) indenting the bladder (HB) and obstructing the ureter (U).

i Bladder tumor (T), invading into the ureter (U), HB = bladder; DK = catheter balloon.

Ureteral stone obstruction

j Gray-scale image: obstruction caused by a hypoechoic mass (arrow).

k Color Doppler image: no vascularity, lack of a twinkling artifact (which mostly can be detected in renal stones). U = ureter, AI = iliac artery.

l Stone obstruction of the ureteral orifice. Distinctive twinkling artifact. Ureteral jet. U = ureter.

390

Retroperitoneal Fibrosis (Ormond Disease)

Fibrosis arising from the region of the L 4 and L 5 vertebrae, with the formation of collagenous connective tissue fibers up to 2 cm thick, can lead to the extensive fibrous encasement of retroperitoneal structures including the psoas muscle, aorta, and vena cava along with the iliac vessels, mesentery, and ureters.

On ultrasound, the ureters are visibly ensheathed and obstructed, leading to chronic urinary stasis. In contrast to other occlusive diseases, a localized obstruction cannot be found. Instead there is a long, rigid, dilated ureteral segment with none of the tortuosity that is usually seen in association with chronic urinary stasis. The fibrosis itself is slightly echogenic and is poorly delineated from other retroperitoneal structures. The detection of fibrotic encasement on other retroperitoneal organs supports the ultrasound impression of fibrosis-induced urinary stasis.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis involving the ureters also occurs in inflammatory disorders

Fig. 11.28 Ormond disease (retroperitoneal fibrosis). |

b Broad, rigid ureter (U) encased in retroperitoneal con- |

a Grade II stasis kidney (N) with a dilated renal pelvis (P). |

nective tissue, recognized here only by the rigid course of |

C = calix. |

the ureter. The connective tissue itself is not visualized |

|

because of its low impedance. |

such as Crohn disease, diverticulitis, sarcoido- |

coma and malignant lymphoma, should be in- |

sis, and radiation-induced fibrosis. Other retro- |

cluded in the differential diagnosis (Fig.11.28). |

peritoneal causes of urinary stasis, such as sar- |

|

Reflux

Vesicoureteral and vesicorenal reflux also lead to dilatation of the ureter and renal pelvis. A distinction is drawn between primary congenital forms of reflux and secondary acquired forms.

Primary forms. Primary forms of reflux (ureterovesical junction obstruction, i. e., refluxing megaureter) are based on developmental abnormalities of the terminal ureter. These may consist of abnormal orifices, ectopic insertions, or an abnormal course of the ureter in the bladder wall. The results are partial or complete dilatation of the ureter and renal pelvis, with risk for developing progressive renal failure. Besides showing initial suggestive signs, ultrasound can furnish information on the degree of urinary obstruction. The detection of reflux is the domain of the excretory urogram and voiding cystogram. Although color Doppler can demonstrate the presence of a ureteral jet, Doppler ultrasound has not yet established itself as a standard study.5

Classification of Reflux

●Grade I: Reflux causes variable dilatation of the ureter, does not reach the renal pelvis.

●Grade II: Reflux reaches the renal pelvis, causes no dilatation of the collecting system; the fornices remain sharp.

●Grade III: Mild or moderate dilatation of the ureter with or without kinking and/ or mild or moderate dilatation of the collecting system; the fornices are blunted.

●Grade IV: Moderate dilatation of the ureter with or without kinking, moderate dilatation of the collecting system; the fornices are blunted; papillary impression is still visible.

●Grade V: Severe dilatation of the ureter with kinking; massive dilatation of the collecting system; papillary impression of the calices is no longer visible.

Secondary forms. Secondary forms of vesi- |

Group (1985), as quoted in Riedmiller and |

corenal reflux are caused by inflammatory or |

Köhl.6 |

postoperative changes in the bladder floor or |

The diagnosis of reflux is made, according to |

by mechanical or functional infravesical ob- |

|

structions (Fig.11.29, Fig.11.53). |

current examination results (review: 7), by in- |

The classification system in the box above |

travesical administration of ultrasound con- |

was devised by the International Reflux Study |

trast agents (“voiding urosonography”). It has |

11

Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

Fig. 11.29 Chronic primary reflux with grade II ureteral |

b Dilated distal ureter. |

dilatation (U) and chronic urinary stasis (urosepsis); ec- |

|

topic ureteral insertion. |

|

a Dilated pelvis. |

|

c Ectopic ureteral insertion, right side. Weak floating sedimentation in the filled bladder (HB). Arrow: diverticula.

391