- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

■ Bile Duct Rarefaction

Localized and Diffuse

|

|

|

|

Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall |

|

|||

Tree |

|

|

|

Bile Duct Rarefaction |

|

|||

Biliary |

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

Localized and Diffuse |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure |

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Cholestasis |

|

|||

PSC and Cirrhosis of the Liver

PSC and Cirrhosis of the Liver

the Liver

Visualization of a rarefied biliary tree, be it |

work-up of the cirrhotic liver the indirect crite- |

severe chronic hepatobiliary disorders, and |

localized or diffuse, by ultrasound plays a role |

rion of an “abnormal vascular architecture” |

thus also to cirrhosis in PSC and in primary |

on its own only in pediatrics (except for the |

also ties in with the rarefied intrahepatic bile |

biliary cirrhosis (PBC), for example. |

segmental bile duct rarefaction sometimes |

ducts. By analogy, this concept applies to all |

|

seen in PSC). However, in the diagnostic |

types of cirrhosis as the common endpoint of |

|

■ Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

No intraductal pressure increase. Dilatation of the bile ducts without concomitant rise in intraductal pressure can be classified into two entities: for the intrahepatic bile ducts this would correspond to Caroli disease (Fig. 3.9), and for the extrahepatic biliary tree the underlying disorder would be congenital cystic malformation of the CBD. It is not true that cholecystectomy always results in a dilated CBD.

Acute pressure increase. Any acute rise in intraductal pressure within the biliary tree, which has to drain about 700 mL of bile per day, will lead to immediate dilatation of the bile ducts (Fig. 3.2b, Fig. 3.10). The intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts are tubes of connective tissue lined with epithelium but lack-

ing any muscle fibers in the wall, and therefore they cannot resist the pressure increase (this observation becomes obvious during any retrograde injection of contrast media into bile ducts with an initially regular diameter). In acute biliary obstruction, the sonographic finding of bile duct dilatation is the first reproducible indication of this rise in pressure, since in intermittent obstruction the biochemical markers (gamma-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST)) will not change or will rise to abnormal values only hours later (6–24 hours). One rather subtle but convincing sonographic sign of the increased pressure in postcholecystectomy patients is the visualization of the cystic duct remnant (Fig. 3.10).

The more pronounced the acute rise in pressure (for instance, in status post cholecystectomy there is no possibility of pressure compensation by the gallbladder), the more pronounced the changes become in the intrahepatic biliary tree (Fig. 3.2b)—dilatation that can be demonstrated quite well (“double-barreled shotgun sign”) at the sonographically easily accessible segments II and III, since there the hepatic triads branch in a plane paralleling the probe (Fig. 3.3). However, this is true only if the tissue surrounding the bile ducts is elastic enough to allow this dilatation; in bile ducts passing through cirrhotic parenchyma, even high intraductal pressure may not result in dilatation.

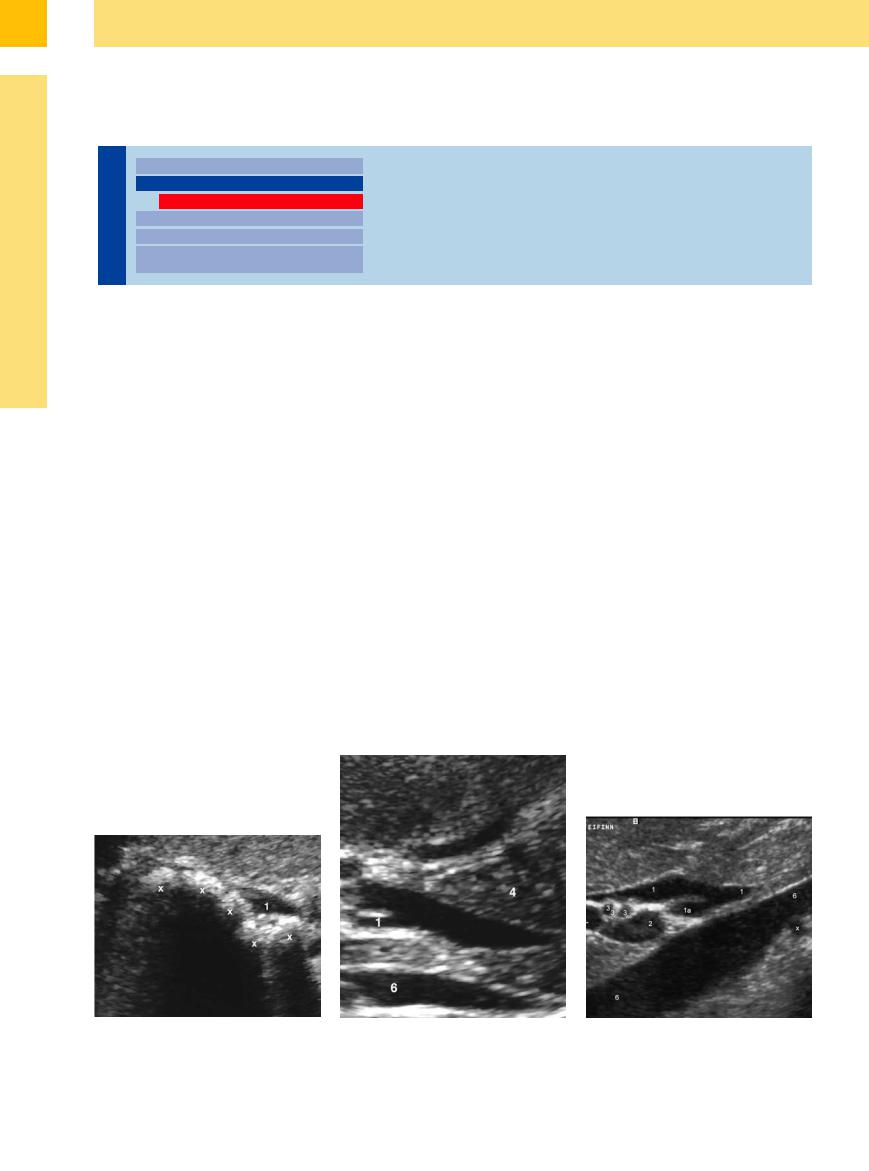

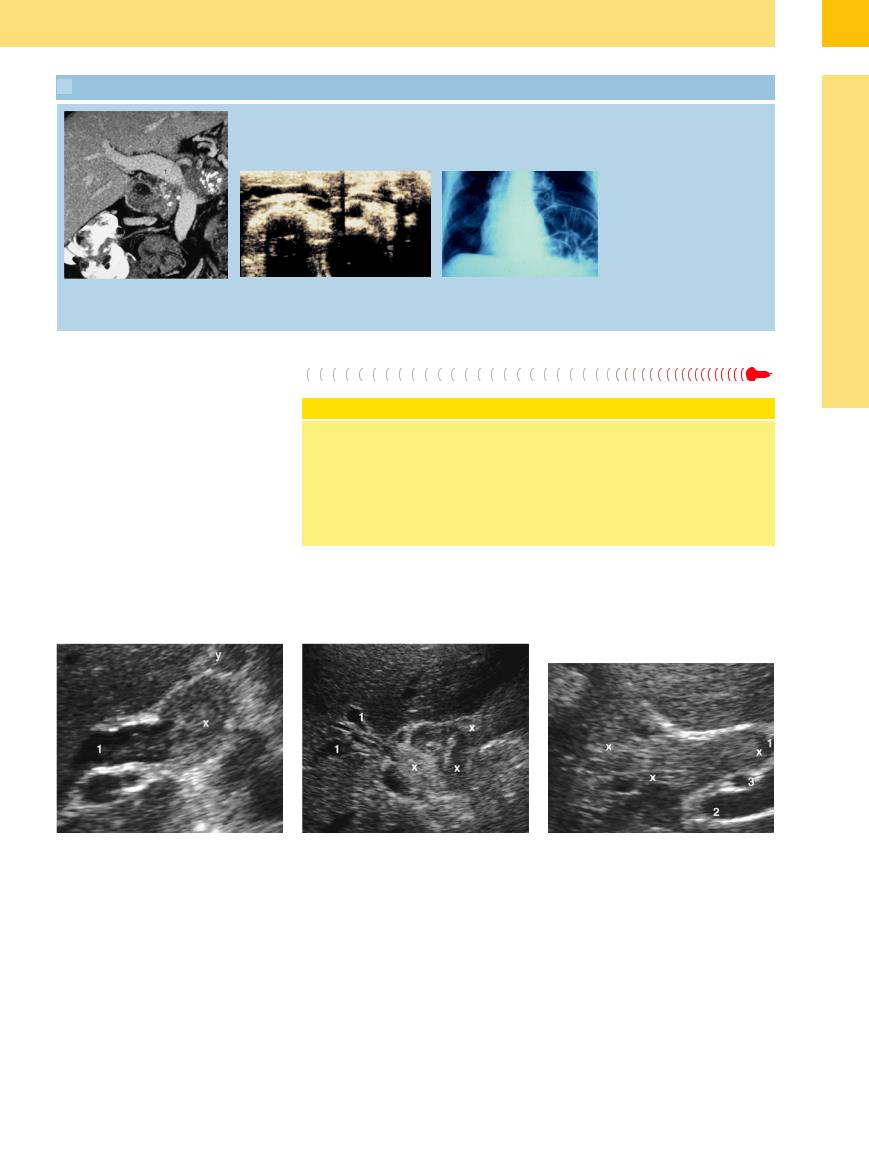

Fig. 3.9 Dilated intrahepatic bile duct (1) with multiple calculi (xx); Caroli disease.

Fig. 3.10

a Dilated cystic duct (1) in pancreatitis of the pancreatic head (4); inferior vena cava (6); portal vein (2).

b CBD (1) and congested stump of the cystic duct (1a); portal vein (2), a double hepatic artery (3), inferior caval vein (6), right renal artery (x).

132

Chronic pressure increase. Chronic pressureinduced dilatation of the bile ducts (Figs. 3.3,

3.8, 3.11, 3.12, 3.13, 3.14) is characterized by maximal dilatation of the ducts involved. Descriptive terms (e. g., the image of the “exfoliated oak tree”) used for the intrahepatic bile duct dilatation convey the situation quite accurately, as long as they trigger the corresponding associations in the mind of the sonographer.

Long-term biliary obstruction with borderline nonicteric compensation is typical of localized intrahepatic obstruction (Fig. 3.13), for instance in CCC (particularly in unilateral Klatskin tumors). If the biliary obstruction is incomplete and takes place over a long period, just 20–25% of parenchyma with regular drainage will still be enough to avoid any manifest jaundice. Biliary obstruction—sometimes ac-

companied by pronounced kinking of the common duct (Fig. 3.12b)—arising at the lower levels and being compensated over a long period is a common finding in well-differentiated periampullary carcinoma (in which case the pancreatic duct will be dilated as well—twin- duct stenosis; Fig. 3.14) and the somewhat rare truly benign stenosis of the papilla of Vater.

3

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

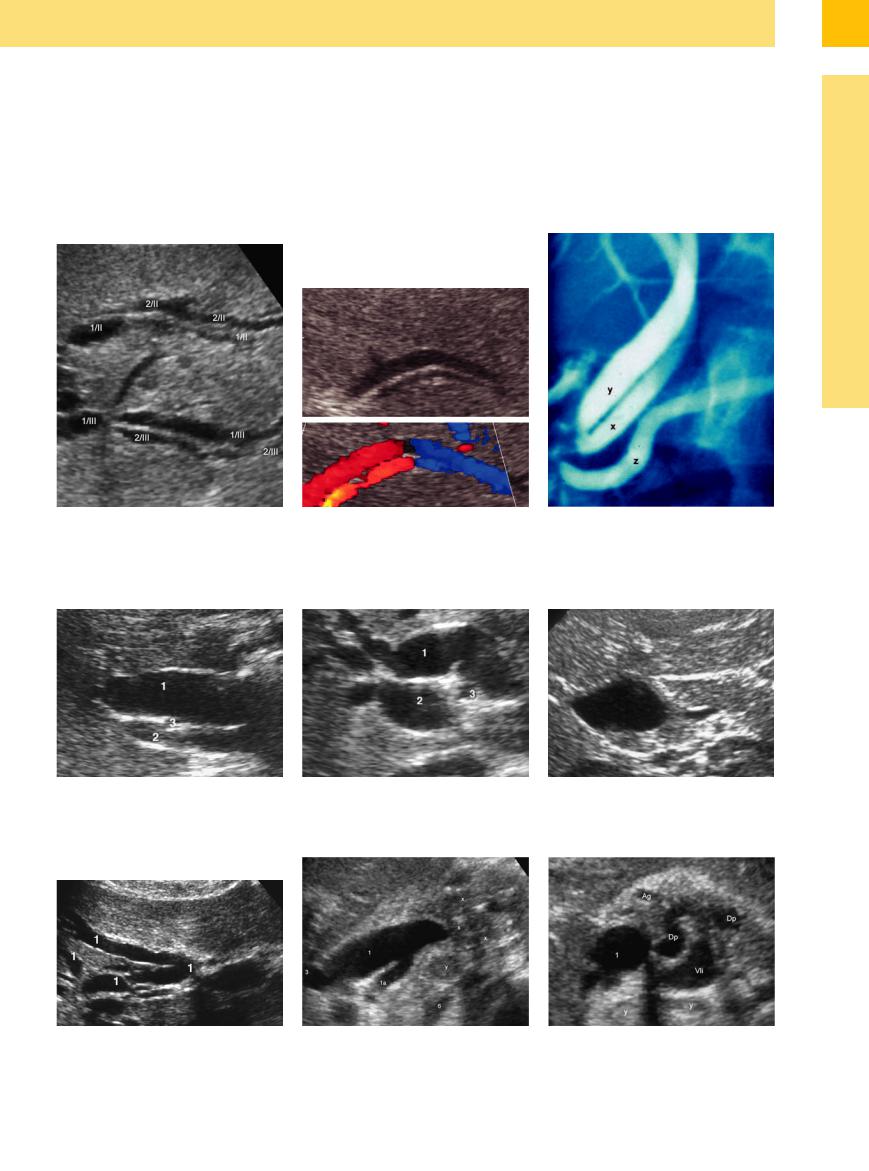

Fig. 3.11

a Intrahepatic dilatation of the intrahepatic bile branches of the segmentsII (1/II) and III (1/III) with accompanying portal vesels (2/II and 2/III in typical arrangement —“dou- ble-barreled shotgun” sign).

Fig. 3.12 Dilated common duct.

a Extensive dilatation of the common duct (1); portal vein (2); hepatic artery (3).

b Double-barreled shotgun sign: in CDS the intrahepatic supposed bile duct depicts as a dilated hepatic artery in liver cirrhosis.

b Kinking of the common duct (1) in long-term pressure increase within the biliary tree; portal vein (2); hepatic artery (3).

c ERC: common orifice of the cystic duct (x) and common hepatic duct (y) of the papilla, lack of a CBD, pancreatic duct (z).

c Choledochocele.

Fig. 3.13 Extensive dilatation of the intrahepatic branches |

Fig. 3.14 a and b Dilated CBS (1) with dilated stump of the cystic duct (1a), pancreatic head tumor (x), lymphadenopathy |

(1) of just the right hepatic lobe in Klatskin tumor. |

(y), hepatic artery (3), inferior caval vein (6), dilated pancreatic duct (dp), gastroduodenal artery (Ag), splenic vein (Vli). |

133

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

Intrahepatic

|

|

|

|

Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall |

|

Tree |

|

||||

|

Bile Duct Rarefaction |

||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure |

|

Biliary |

|

||||

|

|||||

|

|

Intrahepatic |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hilar and Prepancreatic |

|

|

|

|

|

Intrapancreatic |

|

|

|

|

|

Papillary |

|

|

|

|

Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Cholestasis |

|

Intrahepatic Gallstones

Heptocellular Carcinoma (HCC)/Cholangiocellular Carcinoma (CCC)

Intrahepatic  Gallstones

Gallstones

In most cases benign obstruction of the intrahepatic bile ducts is caused by intrahepatic biliary calculi (cholangiolithiasis and hepatolithiasis) (Fig. 3.15).

Focal liver lesions usually do not affect the intrahepatic bile ducts, or at most they displace them without any significant biliodynamic consequences. This is also true for (very) large benign and malignant focal lesions (e. g., voluminous hemangiomas, cysts, or metastases of colorectal cancer).

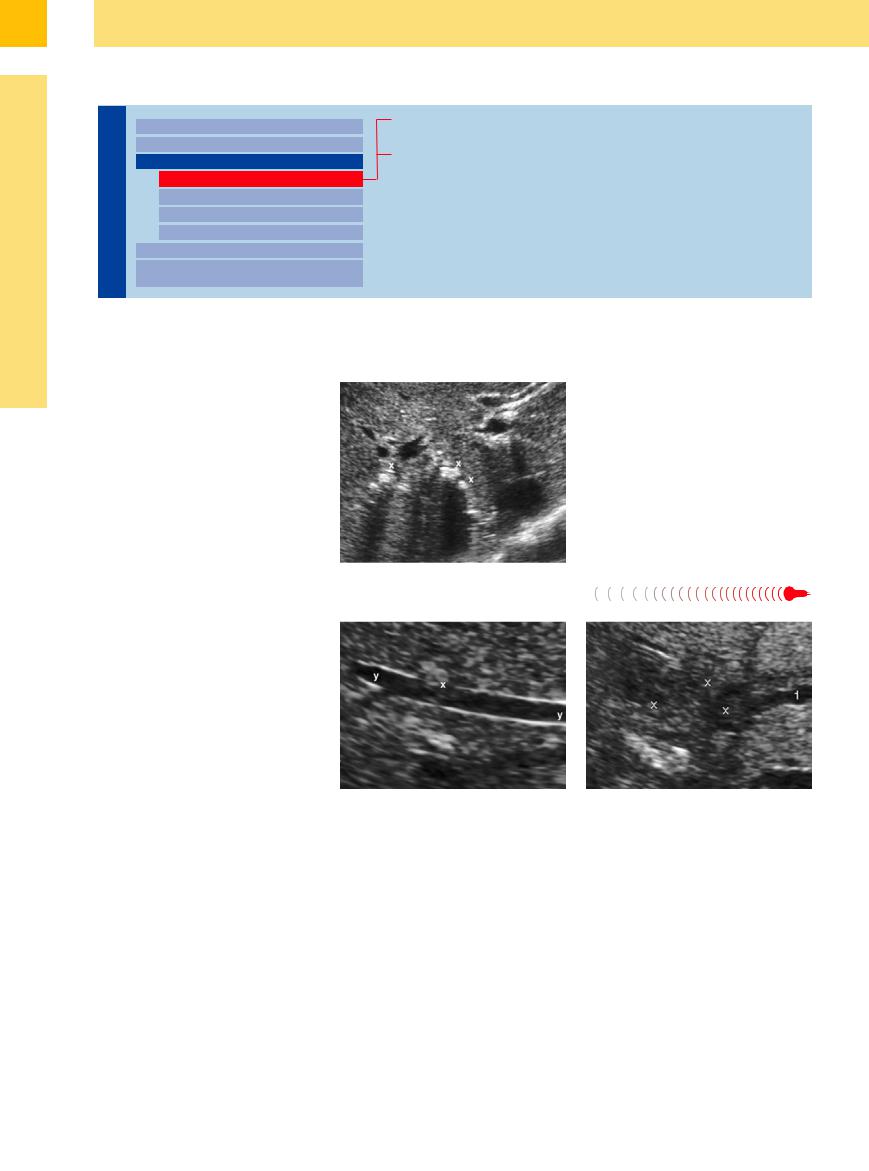

Fig. 3.15 Multiple intrahepatic biliary calculi (hepatoliths) (xx).

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)/Cholangiocellular Carcinoma

Carcinoma (HCC)/Cholangiocellular Carcinoma (CCC)

(CCC)

Even aggressive metastatic spread within the liver usually respects the structures of the biliary tree. HCC may be the one exception, since it is known to invade not only the blood vessels but the bile ducts as well; tumor thrombi in the venous (Fig. 3.16) and biliary vessels (see Figs. 3.20, 3.21, 3.22) are pathognomonic for HCC. As a possible cause of pressure-induced malignant dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts, its incidence is well above that of the (quite rare) true CCC (Fig. 3.17); however, in undifferentiated tumors even pathological histomorphology and/or cytomorphology will sometimes be unable to diagnose precisely whether one is dealing with HCC or CCC.

Fig. 3.16 Small hepatocellular carcinoma (x) invading a hepatic vein (y).

Fig. 3.17 Cholangiocellular carcinoma (x) with localized intrahepatic biliary obstruction (1) (segment II).

134

Hilar and Prepancreatic

Tree |

|

|

|

Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall |

|

Benign Causes of Obstruction |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bile Duct Rarefaction |

|

Malignant Tumors |

|

|

|

|

||||

Biliary |

|

|

|

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Intrahepatic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hilar and Prepancreatic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intrapancreatic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Papillary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Sonographic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cholestasis |

|

|

Benign Causes of Obstruction

of Obstruction

Gallstones. The primary cause of benign biliodynamic obstructions in the porta hepatis and the prepancreatic CBD is biliary calculi ( 3.2), which may differ significantly in terms of shape, size, and number. Gallstones at the hepatic duct confluence and in the CBD will be easier to detect by ultrasound the bigger they are and the more they are encased by fluid. In addition, “young” calculi made up of pure cholesterol (

3.2), which may differ significantly in terms of shape, size, and number. Gallstones at the hepatic duct confluence and in the CBD will be easier to detect by ultrasound the bigger they are and the more they are encased by fluid. In addition, “young” calculi made up of pure cholesterol ( 3.2c) display a higher impedance than old pigmented gallstones of low reflectivity (

3.2c) display a higher impedance than old pigmented gallstones of low reflectivity ( 3.2 d). Direct detection of intrahepatic and common duct biliary calculi may also depend on the quality of the ultrasound platform employed and, primarily, on the diligence and experience of the sonographer. Sonographic visualization of small and minute gallstones (“microlithiasis”) (

3.2 d). Direct detection of intrahepatic and common duct biliary calculi may also depend on the quality of the ultrasound platform employed and, primarily, on the diligence and experience of the sonographer. Sonographic visualization of small and minute gallstones (“microlithiasis”) ( 3.2e,h) is particularly challenging, since their passage through the papilla of Vater appears to be the underlying cause in most cases of so-called idiopathic pancreatitis. When considered in the context of a typical history and clinical findings, ultrasound can detect the presence of such microliths only indirectly by demonstration of the dilated bile ducts. Even in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) studies there is

3.2e,h) is particularly challenging, since their passage through the papilla of Vater appears to be the underlying cause in most cases of so-called idiopathic pancreatitis. When considered in the context of a typical history and clinical findings, ultrasound can detect the presence of such microliths only indirectly by demonstration of the dilated bile ducts. Even in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) studies there is

sometimes lingering doubt about the possible presence of microliths, which may be screened out by the contrast agent. In these cases it pays to insonate the gallbladder immediately after endoscopic retrograde cholangiographic (ERC) cystography: these minute calculi may now be seen in the boundary layer between the (heavier) contrast agent and the (lighter) bile, although they may have escaped detection in previous studies despite patient positioning ( 3.2h). When dealing with small CBD calculi, posterior shadowing may facilitate detection much better than actually looking for the biliary calculus itself (

3.2h). When dealing with small CBD calculi, posterior shadowing may facilitate detection much better than actually looking for the biliary calculus itself ( 3.2b,e).

3.2b,e).

Intraductal gallstones without any clinical or biochemical findings are quite rare and should always be treated by interventional endoscopy (while silent calculi in the gallbladder may be left alone).

A special case of calculus-induced inflammatory bile duct obstruction is Mirizzi syndrome, which can be difficult to visualize on ultrasound (Fig. 3.18).

Hemobilia. In most cases hemobilia is iatrogenic; because of the highly thrombolytic ac-

tivity of bile, biliary obstruction is the exception rather than the norm ( 3.2j).

3.2j).

Cicatricial stenosis. Only rarely is stenosis of the hilar biliary tree and common duct due to scarring the sole cause of the obstruction— most often this will be compensated for a considerable time, and additional factors, such as (micro-)lithiasis, are required for full-blown cholestasis to develop.

Because of their propensity for scar contraction, bilioenteric anastomoses may, however, decompensate without any additional lithic obstruction. These strictures are too short to be amenable to direct sonographic visualization.

Vascular causes. Intramural venous malformations have been described as a vascular cause underlying common duct obstruction.

Lymph node enlargement. Differential diagnosis should always include mechanical cholestasis by lymph node enlargement, no matter what the etiology (Fig. 3.19).

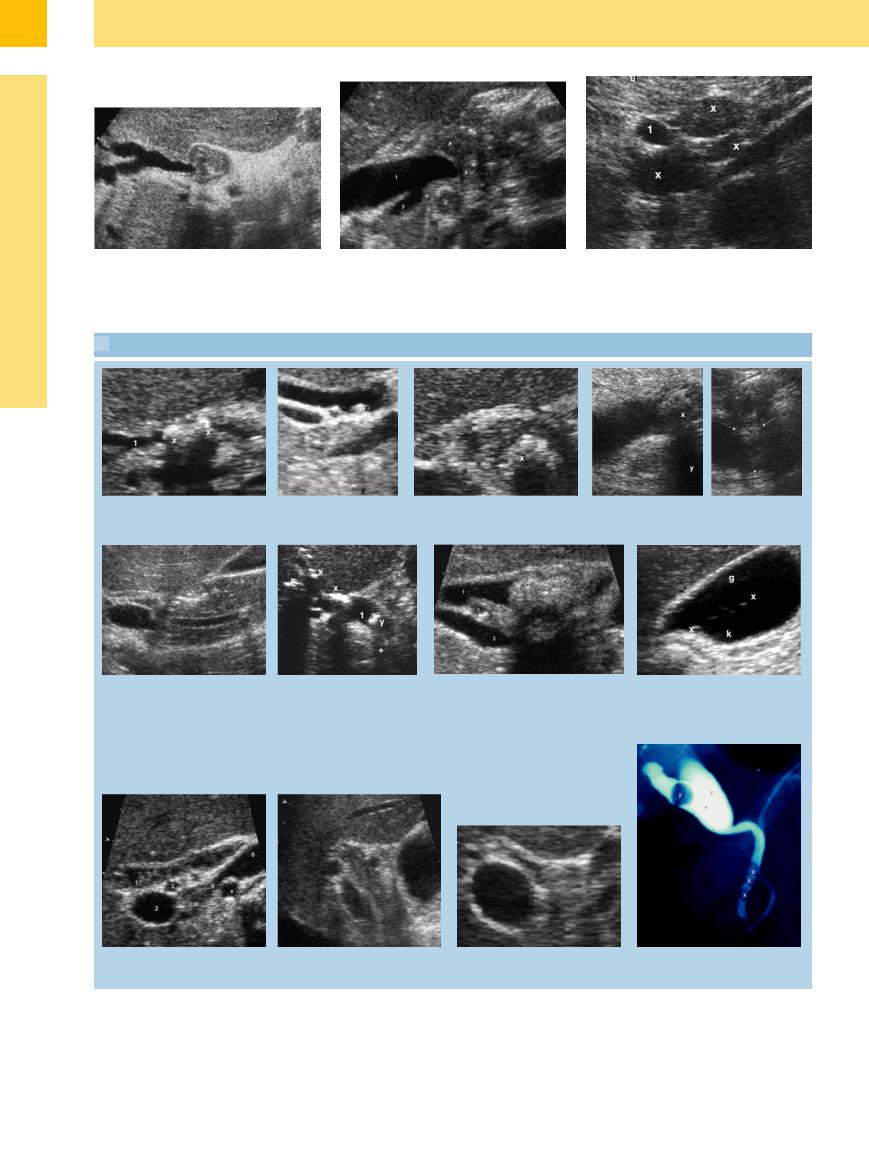

Fig. 3.18 a and b Mirizzi syndrome with cholecystolithiasis in typical infundibular position (x), with hydrops and inflamed thickened wall (y) and biliary outlet obstruction

(1).

3

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

135

3

Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

Fig. 3.18c Biliodigestive anastomosis with unimportant |

d Chronic pancreatitis with calcification (x), obstruction of |

Fig. 3.19 Hodgkin lymphoma (x) with dilatation of the |

(scarred?) stenosis. |

the CBD (1) and dilated cystic duct (y) – lymphadenop- |

CBD (1). |

|

athy (z). |

|

3.2 Choledocholithiasis

3.2 Choledocholithiasis

a Two calculi (xx) in the dilated CBD (1). b Small calculus (x) in the CBD |

c Hyperechoic (cholesterol?) CBD stone |

d Hypoechoic (pigmented?) CBD stone (x) with |

with faint but definite posterior |

(x) with surface defects after extracor- |

posterior shadowing (y). |

shadowing (y). |

poreal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL). |

|

e Preampullary small CBD stone; slightly dilated intrapancreatic CBD.

f Floating intraductal gas bubbles = pneumobilia (x) and CBD calculi (y) with posterior shadowing (+); dilated CBD (1).

g Slightly dilated intrapancreatic CBD (1) with a |

h After ERC and with the patient supine: |

typical stone (x); portal vein (2), hepatic artery, |

floating microliths (xx) marking the |

crossing between (3). |

boundary layer between the lighter bile |

|

(g) and the more viscous contrast agent |

|

(k). |

i Slightly dilated CBD (1), thickening of the wall and sludge after partially effective papillotomy.

j Known clot in hemobilia within the slightly dilated CBD (1); variant of the course of the right hepatic artery (3).

k Barely visible stone in the CBD; no occlusive dilatation in spite of the large stone.

l EAC: three periampullar small stones (x) are barely detectable in US in contrast to a single stone.

136

3.2 Choledocholithiasis (Continued)

3.2 Choledocholithiasis (Continued)

m Imaging of the CBD (1) by CT or MRI is |

n Left: CBD misplaced far to the left, an |

n Right: Corresponding radiograph. |

indicated only in some rare cases (slow |

uncommon course, containing a bile stone. |

|

resolution, high expense; not real-time |

Cause: phrenic nerve exeresis about 40 years |

|

imaging). |

ago. |

|

Malignant Tumors

Once again, when viewed in the direction of bile flow, malignant obstruction at the level of the hilar hepatic confluence or the prepancreatic common duct is due to CCC of the Klatskin type, and in the case of CBD involvement it is the invasive carcinoma of the gallbladder or HCC infiltrating the biliary tree (Figs. 3.20, 3.21, 3.22). Most of these masses are isoechoic with the adjacent hepatic parenchyma and their only evidence is obstruction of the biliary vessels resulting in bile duct dilatation.

Cholangiocellular carcinoma of the Klatskin type, obstructing just one of the two hepatic ducts, is characterized by the difference in echogenicity of the two hepatic lobes, which

Classification of Klatskin Tumors

Klatskin tumors is a collective term for bile duct adenocarcinomas located at the bifurcation of the hepatic duct. They were subdivided into three types by Bismuth and Corlett in 1975, modified to four types.6 Type I tumors involve the common hepatic duct, with no involvement of the right and left secondary ducts. Type II tumors involve

is due to the different amounts of fluid in the parenchyma.

the hepatic duct bifurcation, without involving the secondary intrahepatic ducts. Type III tumors involve the hepatic duct bifurcation, infiltrate the common hepatic duct, and also involve the right (IIIa) or left (IIIb) hepatic ducts. Type IV tumors involve second-order bile ducts. The different types are easily identified by ultrasound.

3

Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

Fig. 3.20 Cholangiocellular carcinoma (x) with enlarged lymph node (y) and tumor projecting into the CBD (1).

Fig. 3.21 Carcinoma of the gallbladder (x) invading the porta hepatis, dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (1).

Fig. 3.22 Hepatocellular carcinoma (x) with peg-shaped invasion of the CBD (1); portal vein (2), hepatic artery (3).

137