- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Vessels

- •1.1 Aorta, Vena Cava, and Peripheral Vessels

- •Aorta, Arteries

- •Anomalies and Variant Positions

- •Dilatation

- •Stenosis

- •Wall Thickening

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Perivascular Mass

- •Vena Cava, Veins

- •Anomalies

- •Dilatation

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Compression, Infiltration

- •1.2 Portal Vein and Its Tributaries

- •Enlarged Lumen Diameter

- •Portal Hypertension

- •Intraluminal Mass

- •Thrombosis

- •Tumor

- •2 Liver

- •Enlarged Liver

- •Small Liver

- •Homogeneous Hypoechoic Texture

- •Homogeneous Hyperechoic Texture

- •Regionally Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Diffuse Inhomogeneous Texture

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Isoechoic Masses

- •Hyperechoic Masses

- •Echogenic Masses

- •Irregular Masses

- •Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions

- •Diagnostic Methods

- •Suspected Diagnosis

- •3 Biliary Tree and Gallbladder

- •3.1 Biliary Tree

- •Thickening of the Bile Duct Wall

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Rarefaction

- •Localized and Diffuse

- •Bile Duct Dilatation and Intraductal Pressure

- •Intrahepatic

- •Hilar and Prepancreatic

- •Intrapancreatic

- •Papillary

- •Abnormal Intraluminal Bile Duct Findings

- •Foreign Body

- •The Seven Most Important Questions

- •3.2 Gallbladder

- •Changes in Size

- •Large Gallbladder

- •Small/Missing Gallbladder

- •Wall Changes

- •General Hypoechogenicity

- •General Hyperechogenicity

- •General Tumor

- •Focal Tumor

- •Intraluminal Changes

- •Hyperechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Nonvisualized Gallbladder

- •Missing Gallbladder

- •Obscured Gallbladder

- •4 Pancreas

- •Diffuse Pancreatic Change

- •Large Pancreas

- •Small Pancreas

- •Hypoechoic Texture

- •Hyperechoic Texture

- •Focal Changes

- •Anechoic Lesion

- •Hypoechoic Lesion

- •Isoechoic Lesion

- •Hyperechoic Lesion

- •Irregular (Complex Structured) Lesion

- •Dilatation of the Pancreatic Duct

- •Marginal/Mild Dilatation

- •Marked Dilatation

- •5 Spleen

- •Nonfocal Changes of the Spleen

- •Diffuse Parenchymal Changes

- •Large Spleen

- •Small Spleen

- •Focal Changes of the Spleen

- •Anechoic Mass

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Hyperechoic Mass

- •Splenic Calcification

- •6 Lymph Nodes

- •Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- •Head/Neck

- •Extremities (Axilla, Groin)

- •Abdominal Lymph Nodes

- •Porta Hepatis

- •Splenic Hilum

- •Mesentery (Celiac, Upper and Lower Mesenteric Station)

- •Stomach

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •Small/Large Intestine

- •Focal Wall Changes

- •Extended Wall Changes

- •Dilated Lumen

- •Narrowed Lumen

- •8 Peritoneal Cavity

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Wall Structures

- •Smooth Margin

- •Irregular Margin

- •Intragastric Processes

- •Intraintestinal Processes

- •9 Kidneys

- •Anomalies, Malformations

- •Aplasia, Hypoplasia

- •Cystic Malformation

- •Anomalies of Number, Position, or Rotation

- •Fusion Anomaly

- •Anomalies of the Renal Calices

- •Vascular Anomaly

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Large Kidneys

- •Small Kidneys

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Irregular Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic or Isoechoic Structure

- •Complex Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •10 Adrenal Glands

- •Enlargement

- •Anechoic Structure

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Complex Echo Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •11 Urinary Tract

- •Malformations

- •Duplication Anomalies

- •Dilatations and Stenoses

- •Dilated Renal Pelvis and Ureter

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Large Bladder

- •Small Bladder

- •Altered Bladder Shape

- •Intracavitary Mass

- •Hypoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Wall Changes

- •Diffuse Wall Thickening

- •Circumscribed Wall Thickening

- •Concavities and Convexities

- •12.1 The Prostate

- •Enlarged Prostate

- •Regular

- •Irregular

- •Small Prostate

- •Regular

- •Echogenic

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •12.2 Seminal Vesicles

- •Diffuse Change

- •Hypoechoic

- •Circumscribed Change

- •Anechoic

- •Echogenic

- •Irregular

- •12.3 Testis, Epididymis

- •Diffuse Change

- •Enlargement

- •Decreased Size

- •Circumscribed Lesion

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Irregular/Echogenic

- •Epididymal Lesion

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Intrascrotal Mass

- •Anechoic or Hypoechoic

- •Echogenic

- •13 Female Genital Tract

- •Masses

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Uterus

- •Abnormalities of Size or Shape

- •Myometrial Changes

- •Intracavitary Changes

- •Endometrial Changes

- •Fallopian Tubes

- •Hypoechoic Mass

- •Anechoic Cystic Mass

- •Solid Echogenic or Nonhomogeneous Mass

- •14 Thyroid Gland

- •Diffuse Changes

- •Enlarged Thyroid Gland

- •Small Thyroid Gland

- •Hypoechoic Structure

- •Hyperechoic Structure

- •Circumscribed Changes

- •Anechoic

- •Hypoechoic

- •Isoechoic

- •Hyperechoic

- •Irregular

- •Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

- •Types of Autonomy

- •15 Pleura and Chest Wall

- •Chest Wall

- •Masses

- •Parietal Pleura

- •Nodular Masses

- •Diffuse Pleural Thickening

- •Pleural Effusion

- •Anechoic Effusion

- •Echogenic Effusion

- •Complex Effusion

- •16 Lung

- •Masses

- •Anechoic Masses

- •Hypoechoic Masses

- •Complex Masses

- •Index

2

Liver

Hypoechoic Masses

|

|

|

Diffuse Changes in Hepatic |

|

Liver |

Parenchyma |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Localized Changes in Hepatic |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Parenchyma |

|

|

|

|

|

Anechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hypoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Isoechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Hyperechoic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Echogenic Masses |

|

|

|

|

Irregular Masses |

|

|

|

Differential Diagnosis of Focal Lesions |

|

|

|

|

||

The typical lesions of liver pathology within the hepatic parenchyma are hypoechoic masses. However, the operator should always be aware of possible “technical glitches” (e. g., improper presettings with the gain too high), when noise will turn anechoic masses into echogenic lesions and thus result in misinterpretation.

Metastasis

Lymphoma

Abscess

Hematoma

Complicated Cyst

Adenoma

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Lipoma

Atypical Hemangioma

Focal Fatty Change

Bile Ducts/Vessels

Metastasis

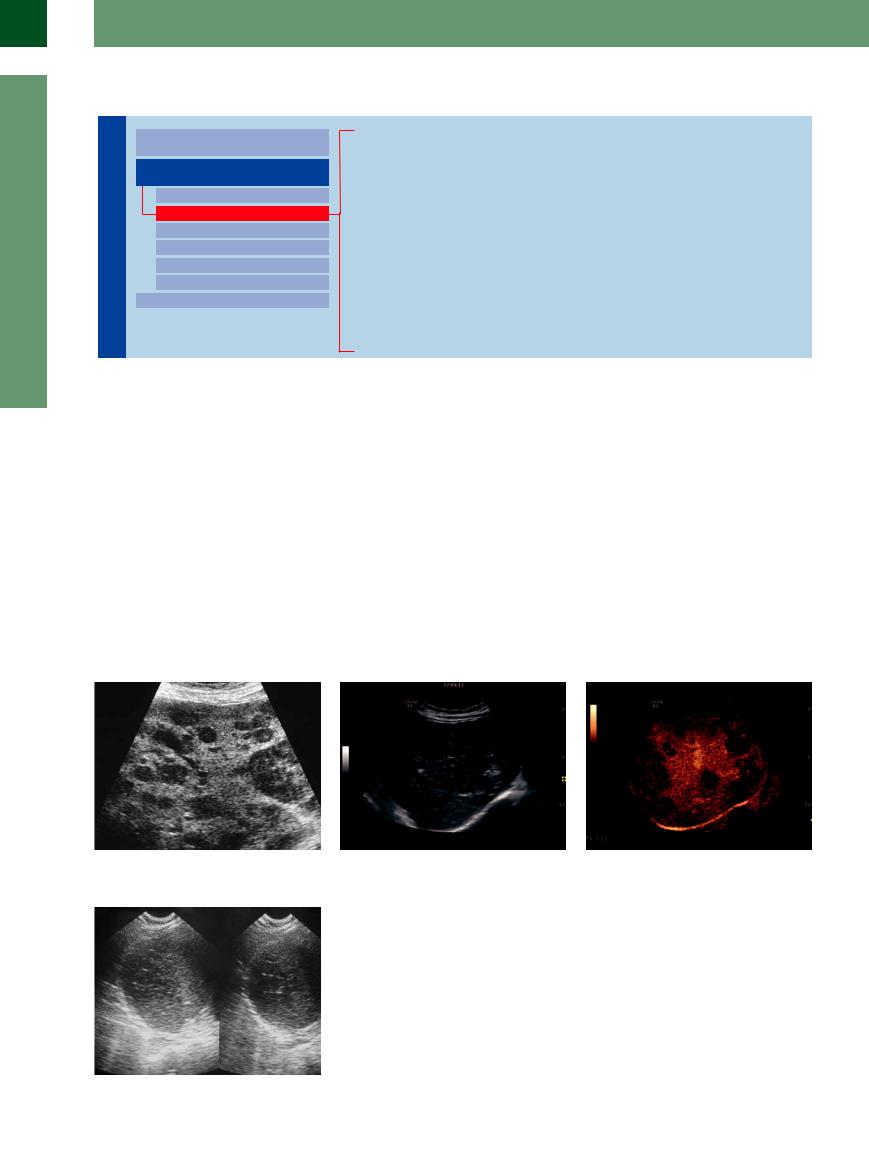

Numerous tumors will deposit hypoechoic metastatic masses in the liver (Figs. 2.70, 2.71, 2.72). These lesions may differ in size and distribution, but in most cases they are small and tend to have an irregular/diffuse margin. Although one cannot, in principle, deduce the type of tumor from the sonographic image alone, these hypoechoic metastatic deposits are quite frequent in undeveloped, un-

differentiated, and actively growing malignancies. The finding of hypoechoic metastases is rather common (but not pathognomonic) in breast cancer, in small cell lung cancer, and in endocrine tumors. Numerous tumors exhibit this hypoechogenicity when initially invading the liver with these small focal metastases. The growing size of the lesion will lead to complications of tumor growth, such as central ne-

crosis and hematoma, and eventually the original hypoechoic appearance will be found only along the active outer rim (so-called “halo sign”). Thus, in cases of rapid tumor growth small hypoechoic masses will quite often be discovered next to large lesions with a halo.

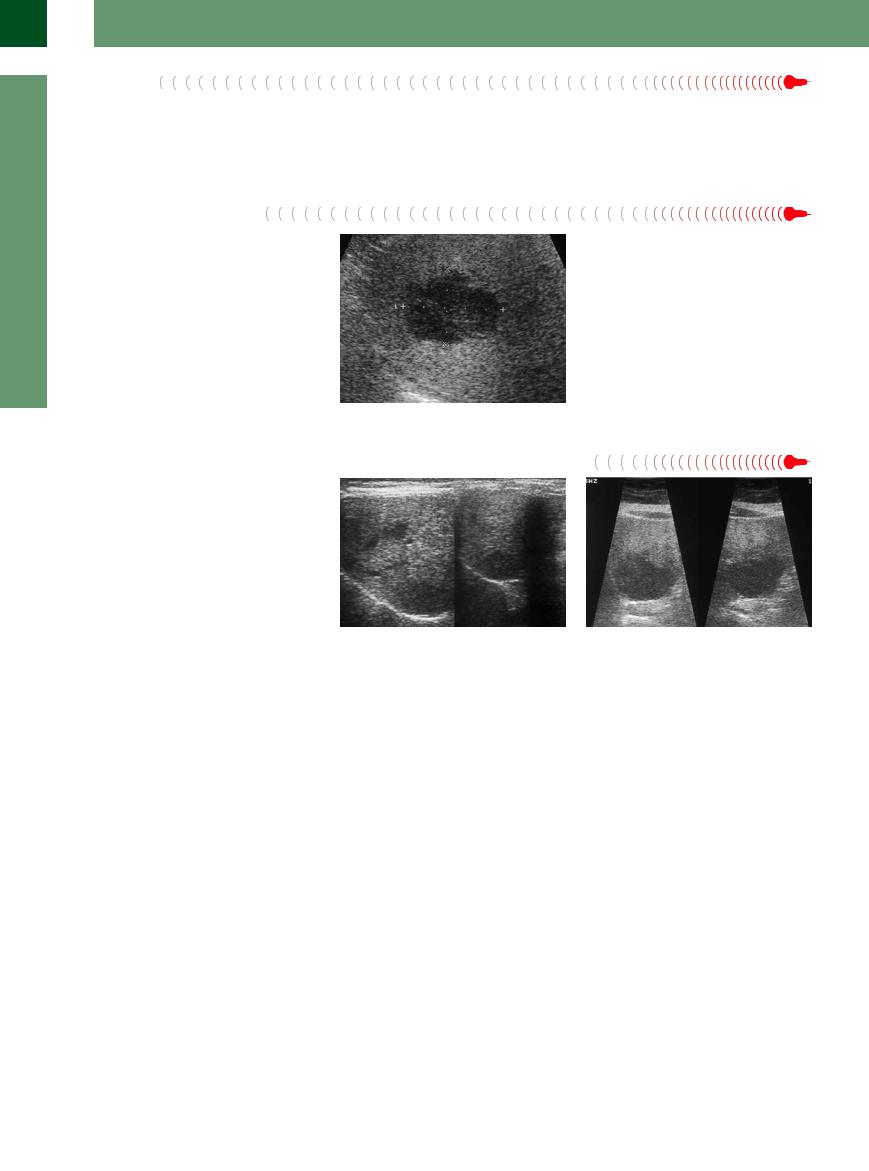

Fig. 2.70 Multiple hypoechoic metastases of small cell carcinoma of the lung.

Fig. 2.71

a Diffuse metastases with hypoechoic patchy infiltratons by metastases of a cecal adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 2.72 Large solitary metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus.

b Unmasked metastases of the cecal carcinoma (Fig. 2.71a) by CEUS.

96

Hepatic Metastases

Primary tumors. The incidence of hepatic metastasis of nonhepatic primaries is about 50 times higher than that of primary cancer of the liver; and in autopsies of patients who have succumbed to nonhepatic malignancies, these metastases are found in 36–40% of cases. The most common primaries are cancer of the lung, colon, stomach, breast, and pancreas as well as renal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, and neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract.

Metastatic spread. The tumors metastasize primarily via the venous system, most often taking the portal route with periportal deposits, and far less frequently via the arterial tree; spread via the lymphatics tends to be the exception. Decreased portal blood flow and the decrease in the number of lectin receptors, which are needed if the tumor cells are to bind to the hepatocytes, are common findings in chronic liver disease and have helped to explain, especially in cirrhosis of the liver, why metastases of nonhepatic primaries are a rather infre-

quent finding. Therefore, any mass detected in a cirrhotic liver has to raise a very high level of suspicion of HCC or granulomatous regeneration.

Echogenicity. The echogenicity of hepatic metastases does not depend very much on the type of primary malignancy but rather on their activity and rate of growth: rapidly growing tumors and the metabolically active rims (halo) of metastases tend to present as hypoechoic images, while slowly growing tumors are inclined toward hyperechogenicity. Although small hepatic lesions tend to be hypoechoic as well, their growth is accompanied by the sequelae of complications such as central necrosis, hematoma, liquefaction, and calcification.

Vascularization. In primary and secondary tumors of the liver, 90–95% of the blood supply arises from the hepatic artery. In color-flow Doppler scanning, metastases tend to be hypovascular (except for HCC and neuroendocrine tumors). The characterization of typical cancerous focal masses

of the liver results from the analysis of their vascularization (progression in time and vascular density) by CEUS. The detection of isoechogenic metastasis can also be dramatically enhanced by CEUS. Two different types of metastasis can be distinguished during the early arterial phase: some are hypervascular (e. g., stomach carcinoma, breast cancer, kidney cell carcinoma), others are hypovascular, showing at most a so-called rim enhancement. Since metastases wash out faster after contrast agent application they can be unmasked during the late parenchymal phase, while the contrast agent still remains in the sinuses (see also Liver Metastases,  2.14, p. 122).

2.14, p. 122).

Further diagnostic modalities. Suspicious lesions in the liver may be subjected to further diagnosis, in addition to CEUS, by specific indirect modalities such as CT, MRI, PET, scintigraphy, or angiography, but in the end metastases have to undergo aspiration cytology—although only if it results in clinical/therapeutic consequences.

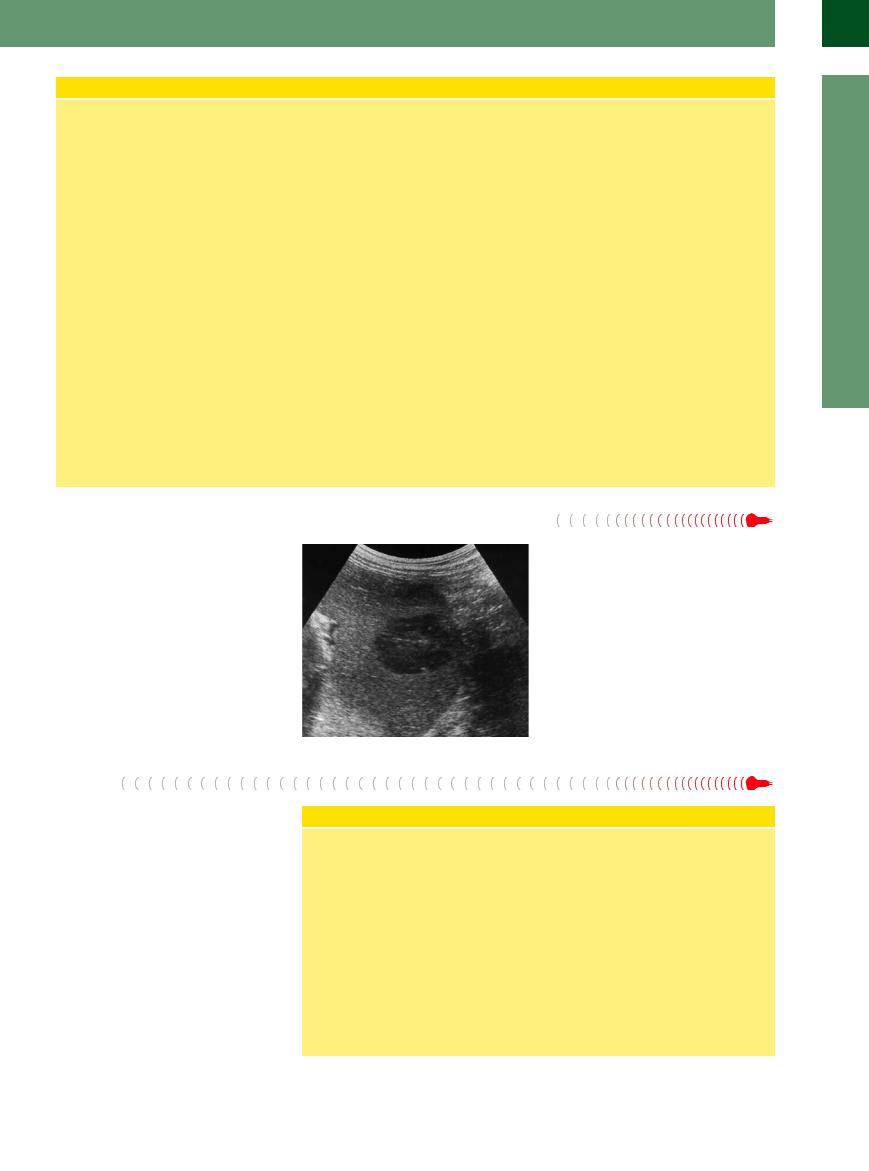

Lymphoma

Hepatic spread of a systemic lymphatic malignancy typically presents as hypoechoic lesions (Fig. 2.73). Quite often these are numerous, vary in size, and are neither spherical nor ovoid in shape but exhibit irregular margins. The difference in the degree of lymphatic infiltration is rather characteristic: apart from solitary, seemingly anechoic lesions (little or no posterior enhancement), there are often irregularly shaped areas, differing in size, of hypoechoic parenchymal infiltration. It is common in these cases to encounter extrahepatic involvement as well, such as splenomegaly with infiltrative changes and lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 2.73 Hypoechoic infiltration of a non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Abscess

Abscess-forming lesions ( 2.8x–z) start as hypoechoic masses, usually with an ill-defined margin. They are located either within the parenchyma or in close proximity to bile ducts. The liver tissue surrounding an abscess is characterized by distinct hypervascularization. As the abscess increases in size this may produce a more hypoechoic, and even anechoic, liquid center, or there may be hyperechoic changes in the center because of necrosis and the formation of gas. Such an abscess will present with a wide, ill-defined hypoechoic halo.

2.8x–z) start as hypoechoic masses, usually with an ill-defined margin. They are located either within the parenchyma or in close proximity to bile ducts. The liver tissue surrounding an abscess is characterized by distinct hypervascularization. As the abscess increases in size this may produce a more hypoechoic, and even anechoic, liquid center, or there may be hyperechoic changes in the center because of necrosis and the formation of gas. Such an abscess will present with a wide, ill-defined hypoechoic halo.

Liver Abscess

Location. Usually, a liver abscess has a diffuse margin and is secondary to bacterial or parasitic infection, which may be unifocal or multifocal. If blood-borne, these abscesses may be found anywhere within the parenchyma; if arising from the biliary tree, they will form close to the bile ducts. If they are the sequelae of interventional procedures, they appear along the drainage or biopsy canal.

Appearance. An acute inflammation may appear as hypoechoic edema surrounding the intraparenchymal abscess, accompanied by inflammatory hypervasculariza-

tion, which can be seen in color Doppler ultrasonography and CEUS. This inflammatory marginal zone delineates the avascular necrotic or pus-filled lumen of the advanced abscess. Follow-up examinations of acute pyogenic abscesses in short succession, independent of clinical signs such as fever, septicemia, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), demonstrate rapid changes in shape as well as in structure, and increase in size and possibly number. Gas formation may herald complications.

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

97

2

Liver

Hematoma

Hemorrhage/hematoma is usually characterized by anechogenicity, but as time goes by and the blood coagulates/becomes organized the image becomes less and less anechoic; quite often compression will produce a hyperechoic halo ( 2.8q,r).

2.8q,r).

Complicated Cyst |

|

|

Cysts may be complicated by hemorrhage or |

Fig. 2.74 Two cysts in the liver. Obliquely imaged and |

|

infection, or they may be scanned in an oblique |

||

complicated cysts may yield the image of a hypoechoic |

||

plane resulting in a hypoechoic rather than |

||

rather than an anechoic cyst. |

||

anechoic image; in these cases ultrasound mor- |

|

|

phology would suggest hemorrhage/hema- |

|

|

toma or an abscess, and not a cyst (Fig. 2.74). |

|

Adenoma

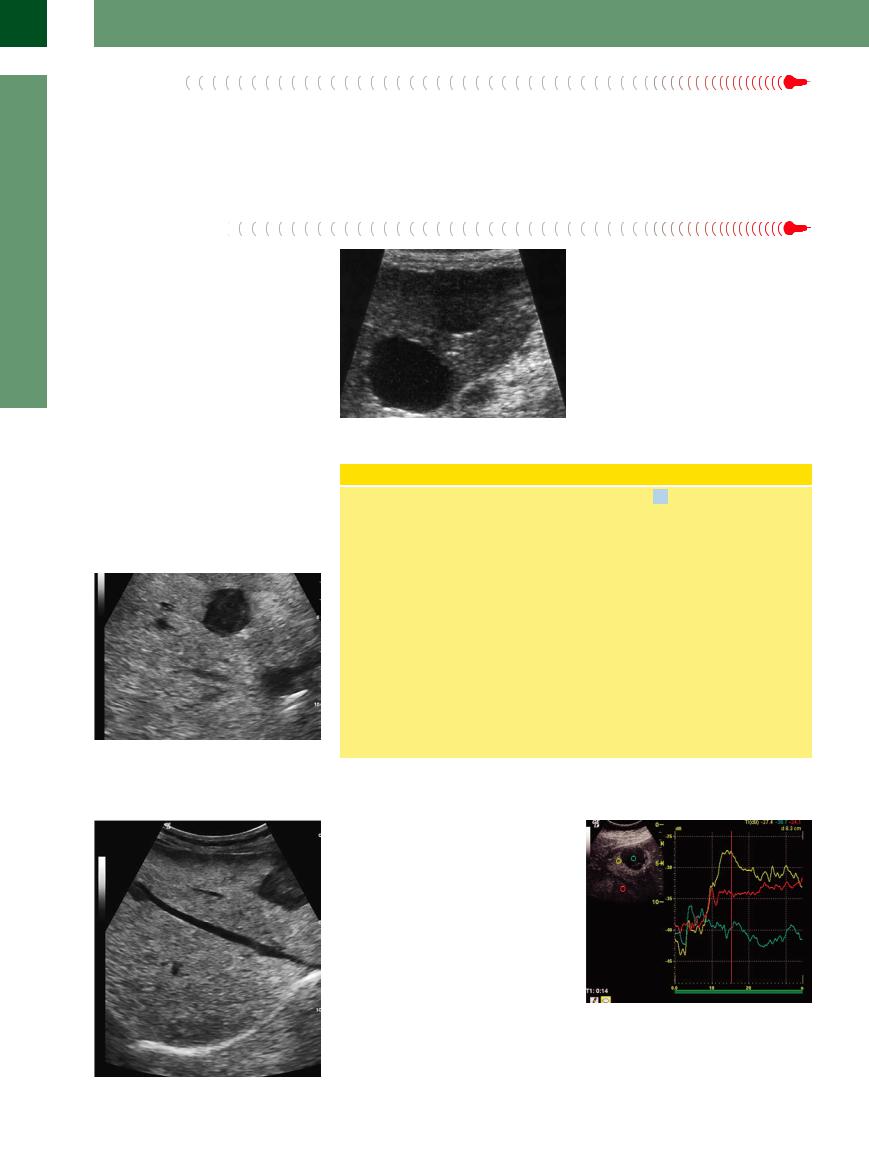

Adenomas of the liver (LCA) are uncommon lesions. They usually exhibit the same texture as the regular parenchyma, but slightly less echogenicity (Figs. 2.75, 2.76, 2.77).

Fig. 2.75 Hypoechoic liver adenoma, histologically confirmed, in a marked fatty liver.

Liver Adenoma

Pathophysiology. Adenomas of the liver are uncommon tumors. They may be hormone induced, and young women are most at risk. In most instances the lesions are solitary, with a diameter between 2 and 30 cm or more. Histologically, these are hepatocytes of clonal growth, the mass showing no capsular delineation. Portal areas and ductal structures (CBO) are missing. LCA are hypervascular. The typical complications arising from these adenomas stem from the increased internal pressure, which will eventually lead to pain, central necrosis/hemorrhage (peliosis hepatis), and rupture. Apart from these typical complications (rare), there is firm evidence of the adenoma malignancy sequence. LCA is not a precursor lesion of HCC.

Fig. 2.77 Time–intensity curve of a liver cell adenoma e (HCA). Demonstration of the dynamic enhancement patterns (early phase, peak enhancement, and late phase) of the contrast agents. The central necrosis (green) is typically nonenhancing, the adenomatous margin (yellow) demonstrates a hyperenhancement (early arterial phase), and in the later phase there is isoenhancement (red). However, this arterial enhancement pattern can also be encountered in HCC and hyperenhancing metastases and

is not pathognomonic of HCA.4

f Fig. 2.76 Hypoechoic liver adenoma, histologically confirmed, in a marked fatty liver (same patient as in

Fig. 2.75).

Ultrasound ( 2.9a–c). Liver adenomas do not exhibit a specific sonographic appearance. Smaller lesions tend to have a somewhat hypoechoic texture, while larger tumors display a coarser echotexture, probably due to the degenerative changes in the tissue, and possibly a hypoechoic rim (target lesion). Complications (central liquefaction/calcification) may also be present. Color-flow Doppler imaging demonstrates the distinct venous vascularization at the margin. In the early arterial phase of CEUS the LCA exhibits a flushlike contrast enhancement and subsequently cannot be distinguished from the surrounding liver parenchyma.

2.9a–c). Liver adenomas do not exhibit a specific sonographic appearance. Smaller lesions tend to have a somewhat hypoechoic texture, while larger tumors display a coarser echotexture, probably due to the degenerative changes in the tissue, and possibly a hypoechoic rim (target lesion). Complications (central liquefaction/calcification) may also be present. Color-flow Doppler imaging demonstrates the distinct venous vascularization at the margin. In the early arterial phase of CEUS the LCA exhibits a flushlike contrast enhancement and subsequently cannot be distinguished from the surrounding liver parenchyma.

98

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) may exhibit all the characteristics of a hypoechoic mass, especially in a hyperechoic fatty liver. However, hypoechogenicity of the lesion is not the most important criterion but rather the textural characteristics of the parenchyma (inhomogeneous, coarse), the architecture of the mass (central stellate scar radiating fibrous septa, characteristic vascular tree), and the blood supply (hypervascularization) ( 2.9 d–z).

2.9 d–z).

Gross Anatomy and Microanatomy of Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

FNH is the second most common benign tumor of the liver, with a diameter usually about 5 cm (1–15 cm). Caused by a focal intrahepatic vessel malformation, the lesion is characterized by a distinct vascular pedicle and hypervascularization. Histologically, it resembles liver parenchyma with circumscribed cirrhotic transformation. The architecture demonstrates the typical stellate scar tissue with a vessel at its center radiating arteries in the fibrous septa that course toward the periphery of the lesion, while being accompanied by lymphocytic infiltration and proliferating bile ducts. The hepatocytes between the fibrous septa form sinusoids with Kupffer cells and make up the bulk of the lesion. The mass is not encapsulated but is delineated by

compressed hepatic parenchyma, where distinct hypervascularization may be found. Significant growth under estrogen replacement therapy has been reported in the literature; malignant transformation does not occur.

Detection of FNH by the various imaging modalities depends on its structural characteristics (vascular pedicle, stellate scar tissue), its typical mulberry-like hypervascularization with a pedicle, central artery radiating centrifugal blood flow seen by color Doppler ultrasonography and CEUS, as well as the histological cellular differentiation of the tumor with the presence of Kupffer cells and proliferating bile ducts.

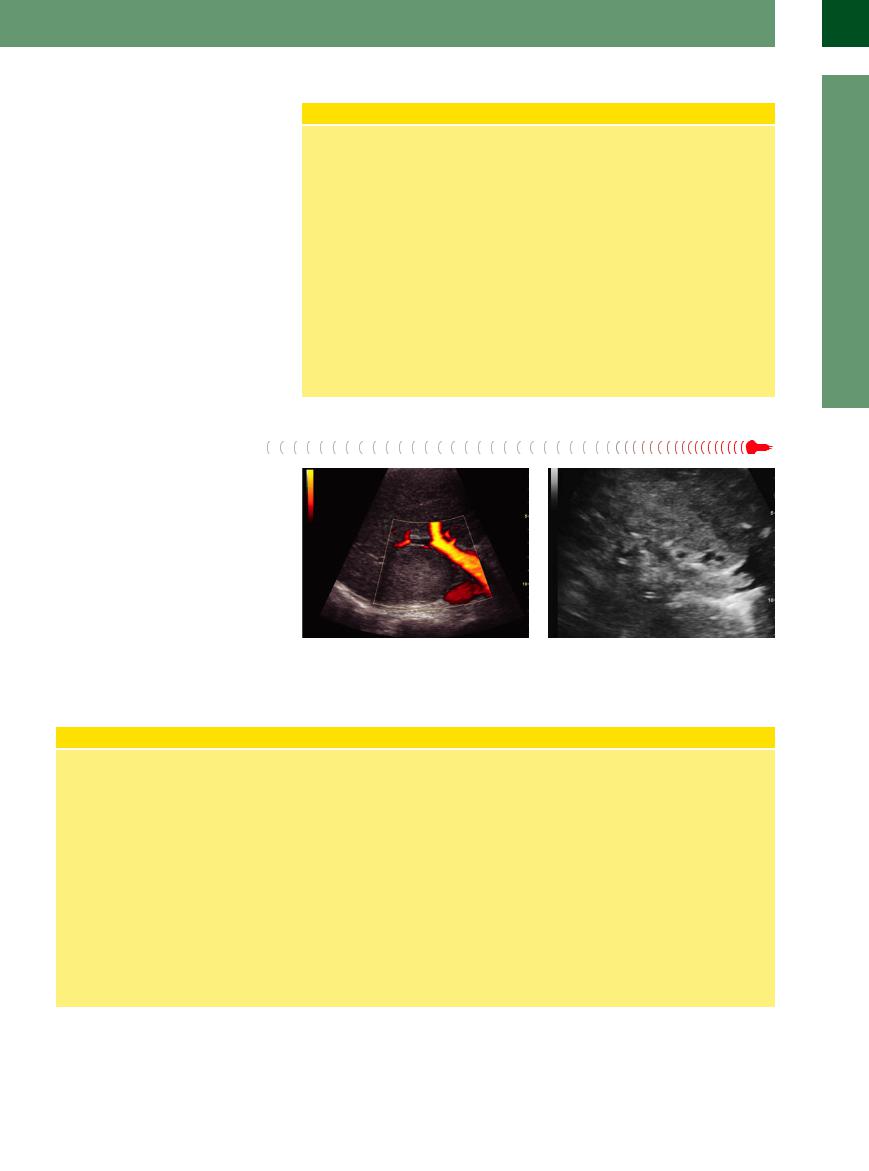

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Carcinoma

One-third of all HCCs will exhibit hypoechogenicity. They have ill-defined margins and typically are found in a cirrhotic liver (Fig. 2.78,  2.10). On color-flow duplex imaging they demonstrate a distinctly hypervascularized blood supply of bizarre irregular outline.

2.10). On color-flow duplex imaging they demonstrate a distinctly hypervascularized blood supply of bizarre irregular outline.

Fig. 2.78 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), isoechoic, in |

Fig. 2.79 HCC growing diffusely. The ill-defined infiltration |

the right liver lobe dorsal and cranial. |

and the invasion into the portal vein raises the suspicion |

|

of HCC. |

Hepatic Carcinomas

Cause. HCC is the most common hepatic malignancy. Although HCC may be found in healthy livers as well, the most prevalent risk for the development of HCC is cirrhosis of the liver due to chronic alcoholism, viral infection (hepatitis B and C), storage diseases such as hemochromatosis or α1-anti- trypsin deficiency, and exposure to aflatoxins.

Histology. Dysplastic nodules are classified as precursors of HCC. The tumor may grow as a solitary focal mass, but in 18–38% of cases it will appear as a multifocal malignancy. The grading includes highly differentiated (including fibrolamellar), moderately differentiated, and anaplastic HCC.

The differential diagnosis must include cholangiocellular carcinoma as well.

Sonographic image. The differences in the histologic findings also help to explain the varied sonographic appearance, with hyperechoic, hypoechoic, and isoechoic masses (compared with the surrounding hepatic parenchyma). In an otherwise healthy liver it is impossible to differentiate between solitary HCC and other tumors; however, one characteristic of HCC is its tumor vascularitis and the tendency to invade the vascular system (Fig. 2.79),2 which may be demonstrated quite well by ultrasound imaging. The observation that malignant metastases are infrequent find-

ings in a cirrhotic or diseased liver also serves to reaffirm the suspicion that any mass detected in a cirrhotic liver has to be regarded as HCC, unless proven otherwise. In color-flow Doppler scans, HCC quite often exhibits bizarre irregular hypervascularization. In CEUS HCC shows bizarre vascularization in the early arterial phase. Depending on the degree of differentiation, poorly differentiated HCC and metastases show a rapid wash-out effect in the subsequent parenchymal phase, whereas a highly differentiated HCC is not distinct from the surrounding tissue during the parenchymal phase.

2

Localized Changes in Hepatic Parenchyma

99

2

Liver

Lipoma

Lipomas are rare. They are encapsulated, smooth, almost anechoic masses with only faint posterior enhancement and are frequently found close to the round ligament.

Atypical Hemangioma

Approximately 5% of all hemangiomas do not |

Fig. 2.80 Atypical hemangioma in the right hepatic lobe. |

exhibit the characteristic hyperechoic paren- |

|

chyma but are less echogenic than the adjacent |

|

hepatic tissue (Fig. 2.80). This may be due to |

|

increased echogenicity of the parenchyma in |

|

the vicinity of the mass, e. g., as part of fatty |

|

changes; in rare cases, one is dealing with |

|

rather hypoechoic hemangiomas of slightly in- |

|

homogeneous texture and frequently ill-de- |

|

fined margins. |

|

Focal Fatty Change

Change

If a hypoechoic lesion is due to focal fatty change, it will typically be found at certain locations: at the inferior aspect of segment IV, near the bifurcation of the portal vein; in the fossa of the gallbladder; and around the hepatic veins. Characteristic features are the frequently map-like appearance of the mass, the fact that it respects segmental interfaces and surfaces, the lack of tissue reaction at the margin, and the undisturbed course of the blood vessels ( 2.6 g,j,l). Focal fatty changes also occur in a disseminated pattern and may imitate tumor infiltration (Fig. 2.81, Fig. 2.82). Both can be differentiated in CEUS: metastatic formations in the late parenchymal phase demonstrate a wash-out and are therefore darker; focal fatty changes demonstrate an identical enhancement to the surrounding liver parenchyma.

2.6 g,j,l). Focal fatty changes also occur in a disseminated pattern and may imitate tumor infiltration (Fig. 2.81, Fig. 2.82). Both can be differentiated in CEUS: metastatic formations in the late parenchymal phase demonstrate a wash-out and are therefore darker; focal fatty changes demonstrate an identical enhancement to the surrounding liver parenchyma.

Fig. 2.81 Focal fatty change with tumor-like hypoechoic lesions (focal sparing in fatty infiltration).

Fig. 2.82 Differential diagnosis in focal fatty change: metastasis, in this case cancer of the colon.

Bile Ducts/Vessels

Bile ducts may be dilated and contain hypoechoic sediment or tumor tissue. The portal and hepatic veins may also be clogged by this hypoechoic thrombotic material. Imaging in the orthogonal plane will confirm the lesion to be a pathological vessel.

100