- •BUSINESSES IN THE BOOK

- •Preface

- •Brief Contents

- •CONTENTS

- •Why Study Strategy?

- •Why Economics?

- •The Need for Principles

- •So What’s the Problem?

- •Firms or Markets?

- •A Framework for Strategy

- •Boundaries of the Firm

- •Market and Competitive Analysis

- •Positioning and Dynamics

- •Internal Organization

- •The Book

- •Endnotes

- •Costs

- •Cost Functions

- •Total Cost Functions

- •Fixed and Variable Costs

- •Average and Marginal Cost Functions

- •The Importance of the Time Period: Long-Run versus Short-Run Cost Functions

- •Sunk versus Avoidable Costs

- •Economic Costs and Profitability

- •Economic versus Accounting Costs

- •Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

- •Demand and Revenues

- •Demand Curve

- •The Price Elasticity of Demand

- •Brand-Level versus Industry-Level Elasticities

- •Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue Functions

- •Theory of the Firm: Pricing and Output Decisions

- •Perfect Competition

- •Game Theory

- •Games in Matrix Form and the Concept of Nash Equilibrium

- •Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Doing Business in 1840

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Doing Business in 1910

- •Business Conditions in 1910: A “Modern” Infrastructure

- •Production Technology

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Government

- •Doing Business Today

- •Modern Infrastructure

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Infrastructure in Emerging Markets

- •Three Different Worlds: Consistent Principles, Changing Conditions, and Adaptive Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Definitions

- •Definition of Economies of Scale

- •Definition of Economies of Scope

- •Economies of Scale Due to Spreading of Product-Specific Fixed Costs

- •Economies of Scale Due to Trade-offs among Alternative Technologies

- •“The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market”

- •Special Sources of Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Density

- •Purchasing

- •Advertising

- •Costs of Sending Messages per Potential Consumer

- •Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

- •Research and Development

- •Physical Properties of Production

- •Inventories

- •Complementarities and Strategic Fit

- •Sources of Diseconomies of Scale

- •Labor Costs and Firm Size

- •Spreading Specialized Resources Too Thin

- •Bureaucracy

- •Economies of Scale: A Summary

- •The Learning Curve

- •The Concept of the Learning Curve

- •Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

- •Learning and Organization

- •The Learning Curve versus Economies of Scale

- •Diversification

- •Why Do Firms Diversify?

- •Efficiency-Based Reasons for Diversification

- •Scope Economies

- •Internal Capital Markets

- •Problematic Justifications for Diversification

- •Diversifying Shareholders’ Portfolios

- •Identifying Undervalued Firms

- •Reasons Not to Diversify

- •Managerial Reasons for Diversification

- •Benefits to Managers from Acquisitions

- •Problems of Corporate Governance

- •The Market for Corporate Control and Recent Changes in Corporate Governance

- •Performance of Diversified Firms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Make versus Buy

- •Upstream, Downstream

- •Defining Boundaries

- •Some Make-or-Buy Fallacies

- •Avoiding Peak Prices

- •Tying Up Channels: Vertical Foreclosure

- •Reasons to “Buy”

- •Exploiting Scale and Learning Economies

- •Bureaucracy Effects: Avoiding Agency and Influence Costs

- •Agency Costs

- •Influence Costs

- •Organizational Design

- •Reasons to “Make”

- •The Economic Foundations of Contracts

- •Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

- •Bounded Rationality

- •Difficulties Specifying or Measuring Performance

- •Asymmetric Information

- •The Role of Contract Law

- •Coordination of Production Flows through the Vertical Chain

- •Leakage of Private Information

- •Transactions Costs

- •Relationship-Specific Assets

- •Forms of Asset Specificity

- •The Fundamental Transformation

- •Rents and Quasi-Rents

- •The Holdup Problem

- •Holdup and Ex Post Cooperation

- •The Holdup Problem and Transactions Costs

- •Contract Negotiation and Renegotiation

- •Investments to Improve Ex Post Bargaining Positions

- •Distrust

- •Reduced Investment

- •Recap: From Relationship-Specific Assets to Transactions Costs

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •What Does It Mean to Be “Integrated?”

- •The Property Rights Theory of the Firm

- •Alternative Forms of Organizing Transactions

- •Governance

- •Delegation

- •Recapping PRT

- •Path Dependence

- •Making the Integration Decision

- •Technical Efficiency versus Agency Efficiency

- •The Technical Efficiency/Agency Efficiency Trade-off

- •Real-World Evidence

- •Double Marginalization: A Final Integration Consideration

- •Alternatives to Vertical Integration

- •Tapered Integration: Make and Buy

- •Franchising

- •Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

- •Implicit Contracts and Long-Term Relationships

- •Business Groups

- •Keiretsu

- •Chaebol

- •Business Groups in Emerging Markets

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitor Identification and Market Definition

- •The Basics of Competitor Identification

- •Example 5.1 The SSNIP in Action: Defining Hospital Markets

- •Putting Competitor Identification into Practice

- •Empirical Approaches to Competitor Identification

- •Geographic Competitor Identification

- •Measuring Market Structure

- •Market Structure and Competition

- •Perfect Competition

- •Many Sellers

- •Homogeneous Products

- •Excess Capacity

- •Monopoly

- •Monopolistic Competition

- •Demand for Differentiated Goods

- •Entry into Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Oligopoly

- •Cournot Quantity Competition

- •The Revenue Destruction Effect

- •Cournot’s Model in Practice

- •Bertrand Price Competition

- •Why Are Cournot and Bertrand Different?

- •Evidence on Market Structure and Performance

- •Price and Concentration

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •6: Entry and Exit

- •Some Facts about Entry and Exit

- •Entry and Exit Decisions: Basic Concepts

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Bain’s Typology of Entry Conditions

- •Analyzing Entry Conditions: The Asymmetry Requirement

- •Structural Entry Barriers

- •Control of Essential Resources

- •Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Marketing Advantages of Incumbency

- •Barriers to Exit

- •Entry-Deterring Strategies

- •Limit Pricing

- •Is Strategic Limit Pricing Rational?

- •Predatory Pricing

- •The Chain-Store Paradox

- •Rescuing Limit Pricing and Predation: The Importance of Uncertainty and Reputation

- •Wars of Attrition

- •Predation and Capacity Expansion

- •Strategic Bundling

- •“Judo Economics”

- •Evidence on Entry-Deterring Behavior

- •Contestable Markets

- •An Entry Deterrence Checklist

- •Entering a New Market

- •Preemptive Entry and Rent Seeking Behavior

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Microdynamics

- •Strategic Commitment

- •Strategic Substitutes and Strategic Complements

- •The Strategic Effect of Commitments

- •Tough and Soft Commitments

- •A Taxonomy of Commitment Strategies

- •The Informational Benefits of Flexibility

- •Real Options

- •Competitive Discipline

- •Dynamic Pricing Rivalry and Tit-for-Tat Pricing

- •Why Is Tit-for-Tat So Compelling?

- •Coordinating on the Right Price

- •Impediments to Coordination

- •The Misread Problem

- •Lumpiness of Orders

- •Information about the Sales Transaction

- •Volatility of Demand Conditions

- •Facilitating Practices

- •Price Leadership

- •Advance Announcement of Price Changes

- •Most Favored Customer Clauses

- •Uniform Delivered Prices

- •Where Does Market Structure Come From?

- •Sutton’s Endogenous Sunk Costs

- •Innovation and Market Evolution

- •Learning and Industry Dynamics

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •8: Industry Analysis

- •Performing a Five-Forces Analysis

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power and Buyer Power

- •Strategies for Coping with the Five Forces

- •Coopetition and the Value Net

- •Applying the Five Forces: Some Industry Analyses

- •Chicago Hospital Markets Then and Now

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Commercial Airframe Manufacturing

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Professional Sports

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Professional Search Firms

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitive Advantage Defined

- •Maximum Willingness-to-Pay and Consumer Surplus

- •From Maximum Willingness-to-Pay to Consumer Surplus

- •Value-Created

- •Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

- •Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

- •Analyzing Value Creation

- •Value Creation and the Value Chain

- •Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

- •Generic Strategies

- •The Strategic Logic of Cost Leadership

- •The Strategic Logic of Benefit Leadership

- •Extracting Profits from Cost and Benefit Advantage

- •Comparing Cost and Benefit Advantages

- •“Stuck in the Middle”

- •Diagnosing Cost and Benefit Drivers

- •Cost Drivers

- •Cost Drivers Related to Firm Size, Scope, and Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Independent of Firm Size, Scope, or Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Related to Organization of the Transactions

- •Benefit Drivers

- •Methods for Estimating and Characterizing Costs and Perceived Benefits

- •Estimating Costs

- •Estimating Benefits

- •Strategic Positioning: Broad Coverage versus Focus Strategies

- •Segmenting an Industry

- •Broad Coverage Strategies

- •Focus Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The “Shopping Problem”

- •Unraveling

- •Alternatives to Disclosure

- •Nonprofit Firms

- •Report Cards

- •Multitasking: Teaching to the Test

- •What to Measure

- •Risk Adjustment

- •Presenting Report Card Results

- •Gaming Report Cards

- •The Certifier Market

- •Certification Bias

- •Matchmaking

- •When Sellers Search for Buyers

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Market Structure and Threats to Sustainability

- •Threats to Sustainability in Competitive and Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Threats to Sustainability under All Market Structures

- •Evidence: The Persistence of Profitability

- •The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Imperfect Mobility and Cospecialization

- •Isolating Mechanisms

- •Impediments to Imitation

- •Legal Restrictions

- •Superior Access to Inputs or Customers

- •The Winner’s Curse

- •Market Size and Scale Economies

- •Intangible Barriers to Imitation

- •Causal Ambiguity

- •Dependence on Historical Circumstances

- •Social Complexity

- •Early-Mover Advantages

- •Learning Curve

- •Reputation and Buyer Uncertainty

- •Buyer Switching Costs

- •Network Effects

- •Networks and Standards

- •Competing “For the Market” versus “In the Market”

- •Knocking off a Dominant Standard

- •Early-Mover Disadvantages

- •Imperfect Imitability and Industry Equilibrium

- •Creating Advantage and Creative Destruction

- •Disruptive Technologies

- •The Productivity Effect

- •The Sunk Cost Effect

- •The Replacement Effect

- •The Efficiency Effect

- •Disruption versus the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Innovation and the Market for Ideas

- •The Environment

- •Factor Conditions

- •Demand Conditions

- •Related Supplier or Support Industries

- •Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Principal–Agent Relationship

- •Combating Agency Problems

- •Performance-Based Incentives

- •Problems with Performance-Based Incentives

- •Preferences over Risky Outcomes

- •Risk Sharing

- •Risk and Incentives

- •Selecting Performance Measures: Managing Trade-offs between Costs

- •Do Pay-for-Performance Incentives Work?

- •Implicit Incentive Contracts

- •Subjective Performance Evaluation

- •Promotion Tournaments

- •Efficiency Wages and the Threat of Termination

- •Incentives in Teams

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •13: Strategy and Structure

- •An Introduction to Structure

- •Individuals, Teams, and Hierarchies

- •Complex Hierarchy

- •Departmentalization

- •Coordination and Control

- •Approaches to Coordination

- •Types of Organizational Structures

- •Functional Structure (U-form)

- •Multidivisional Structure (M-form)

- •Matrix Structure

- •Matrix or Division? A Model of Optimal Structure

- •Network Structure

- •Why Are There So Few Structural Types?

- •Structure—Environment Coherence

- •Technology and Task Interdependence

- •Efficient Information Processing

- •Structure Follows Strategy

- •Strategy, Structure, and the Multinational Firm

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Social Context of Firm Behavior

- •Internal Context

- •Power

- •The Sources of Power

- •Structural Views of Power

- •Do Successful Organizations Need Powerful Managers?

- •The Decision to Allocate Formal Power to Individuals

- •Culture

- •Culture Complements Formal Controls

- •Culture Facilitates Cooperation and Reduces Bargaining Costs

- •Culture, Inertia, and Performance

- •A Word of Caution about Culture

- •External Context, Institutions, and Strategies

- •Institutions and Regulation

- •Interfirm Resource Dependence Relationships

- •Industry Logics: Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Glossary

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

240 • Chapter 7 • Dynamics: Competing Across Time

These and similar examples offer several insights for firms attempting to coordinate on price or other decisions. Firms are likely to settle on round number price points (e.g., $300 for digital music players, or perhaps cost plus $100) and round number price increases (e.g., 10 percent annual increases, or perhaps cost plus 5 percent). Even splits of market share are likely to outlast other, less obvious divisions. Status quo market shares are also sustainable. Coordination is likely to be easier when competitors sell products that are nearly identical. Coordination is likely to be difficult in competitive environments that are turbulent and rapidly changing.

IMPEDIMENTS TO COORDINATION

Even if firms coordinate on tit-for-tat pricing, harmony may not ensue. There are many other impediments to implementing a successful tit-for-tat strategy.

The Misread Problem

Tit-for-tat strategy assumes that firms can perfectly observe each other’s actions. But rivals will sometimes misread their rivals. By “misread,” we mean that either (1) a firm mistakenly believes a competitor is charging one price when it is really charging another or (2) a firm misunderstands the reasons for a competitor’s pricing decision or their own change in market share. In these situations, a firm might mistakenly believe that its competitor has lowered prices in an attempt to break the “collusive agreement.” If the firms are playing tit-for-tat, then rounds of price cutting may ensue, merely because of a misunderstanding.

McKinsey consultants Robert Garda and Michael Marn suggest that some realworld price wars are not prompted by deliberate attempts by one firm to steal business from its competitors.24 Instead, the wars stem from misreads. To illustrate their point, Garda and Marn cite the example of a tire manufacturer that sold a particular tire at an invoice price of $35, but with an end-of-year volume bonus of $2 and a marketing allowance of $1.50, the manufacturer’s net price was really $31.50.25 This company received reports from its regional sales personnel that a rival firm was selling a competing tire at an invoice price of $32.00. In response, the manufacturer lowered its invoice price by $3.00, reducing its net price to $28.50. The manufacturer later learned that its competitor was not offering marketing allowances or volume discounts. By misreading its competitor’s price and reacting immediately, the tire manufacturer precipitated a vicious price war that hurt both firms.

Garda and Marn emphasize that to avoid overreacting to apparent price cuts by competitors, companies should carefully ascertain the details of the competitive initiative and figure out what is driving it before responding. In the same vein, Avinash Dixit and Barry Nalebuff have argued that when misreads are possible, pricing strategies that are less provocable and more forgiving than tit-for-tat are desirable.26 It may be desirable to ignore what appears to be an uncooperative move by one’s competitor if the competitor might revert to cooperative behavior in the next period.

Lumpiness of Orders

Orders are lumpy when sales occur relatively infrequently in large batches as opposed to being smoothly distributed over the year. Lumpy orders are an important characteristic of such industries as airframe manufacturing, shipbuilding, and supercomputers.

Impediments to Coordination • 241

EXAMPLE 7.4 FORGIVENESS AND PROVOCABILITY: DOW CHEMICALS

AND THE MARKET FOR REVERSE OSMOSIS MEMBRANES

Achieving the right balance between provocability and forgiveness is important, but it can be difficult to do. Dow Chemicals learned this lesson in the mid-1990s in the market for reverse osmosis membranes, an expensive component used in environmental systems for wastewater treatment and water purification. Dow sells this product to large industrial distributors that, in turn, resell it to end users.

Until 1989, Dow held a patent on its FilmTec membrane and had the U.S. market entirely to itself. In 1989, however, the U.S. government made Dow’s patent public property on the grounds that the government had co-funded the development of the technology. Shortly thereafter, a Japanese firm entered the market with a “clone” of Dow’s FilmTec membrane.

In 1989, Dow’s price was $1,400 per membrane. Over the next seven years, the Japanese competitor reduced its price to about $385 per unit. Over this period, Dow also reduced its price. With slight differentiation based on superior service support and perceived quality, Dow’s price bottomed out at about $405 per unit.

During the downward price spiral, Dow alternated back and forth between forgiving and aggressive responses to its competitor’s pricing moves as Dow sought to ascertain its rival’s motives and persuade it to keep industry prices high. On three different occasions, Dow raised the price of its membrane. Its competitor never followed Dow’s increases, and (consistent with tit-for-tat pricing) Dow ultimately rescinded its price increase each time.

During this period, Dow also attempted several strategic moves to insulate itself from price competition and soften the pricing behavior of its competitor. For example, Dow invested in product quality to improve the performance of its membranes. It also tried to remove distributors’ focus on price by heavily advertising its membrane’s superior performance features. These moves were only moderately successful, however, and Dow was unable to gain a price premium greater than 13 percent.

Eventually, Dow learned that its competitor manufactured its product in Mexico, giving it a cost advantage based on low-cost labor. It also learned that in 1991 the competitor had built a large plant and that its aggressive pricing moves were, in part, prompted by a desire to keep that plant operating at full capacity. Based on this information, Dow abandoned its efforts to soften price competition, either through forgiving pricing moves or strategic commitments aimed at changing the equilibrium in the pricing game. Dow’s current strategy is to bypass industrial distributors and sell its product directly to end users. This move was motivated by Dow’s discovery that, despite the decreases in manufacturers’ prices, distributors’ prices to end users remained fairly constant. It is not clear that this strategy would help insulate Dow from price competition. Dow’s competitor can presumably imitate this strategy and deal directly with end users as well. It is hard to imagine pricing rivalry in this industry becoming less aggressive.

Lumpy orders reduce the frequency of competitive interactions between firms, lengthen the time required for competitors to react to price reductions, and thereby make price cutting more attractive.

Information about the Sales Transaction

When sales transactions are “public,” deviations from cooperative pricing are easier to detect than when prices are secret. For example, all airlines closely monitor each other’s prices using computerized reservation systems and immediately know when a carrier has cut fares. By contrast, prices in many industrial goods markets are

242 • Chapter 7 • Dynamics: Competing Across Time

privately negotiated between buyers and sellers, so it may be difficult for a firm to learn whether a competitor has cut its price. Because retaliation can occur more quickly when prices are public than when they are secret, price cutting to steal market share from competitors is likely to be less attractive, enhancing the chances that cooperative pricing can be sustained.

Secrecy is a significant problem when transactions involve other dimensions besides a list or an invoice price, as they often do in business-to-business marketing settings. For example, a manufacturer of cookies, such as Keebler, that wants to steal business from a competitor, say Nabisco, can cut its “net price” by increasing trade allowances to retailers or by extending more favorable trade credit terms. Because it is often more difficult to monitor trade allowance deals or credit terms than list prices, competitors may find it difficult to detect business-stealing behavior, hindering their ability to retaliate. Business practices that facilitate secret price cutting create a prisoners’ dilemma. Each firm individually prefers to use them, but the industry is collectively worse off when all firms do so.

Deviations from cooperative pricing are also difficult to detect when product attributes are customized to individual buyers, as in airframe manufacturing or the production of diesel locomotives. When products are tailor-made to individual buyers, a seller may be able to increase its market share by altering the design of the product or by throwing in “extras,” such as spare parts or a service agreement. These are typically more difficult to observe than the list price, complicating the ability of firms to monitor competitors’ behavior.

Secret or complex transaction terms can intensify price competition not only because price matching becomes a less effective deterrent to price-cutting behavior, but also because misreads become more likely. Firms are more likely to misinterpret a competitive move, such as a reduction in list prices, as an aggressive attempt to steal business, when they cannot fully observe all the other terms competitors are offering. When this happens, the odds of accidental price wars breaking out rise. To the extent that a firm’s pricing behavior is forgiving, the effects of misreads may be containable.

Volatility of Demand Conditions

Price cutting is harder to verify when market demand conditions are volatile and a firm can observe only its own volume and not that of its rival. If a firm’s sales unexpectedly fall, it will naturally suspect that one of its competitors has cut price and is taking business from it. Demand volatility is an especially serious problem when production involves substantial fixed costs. Then, marginal costs decline rapidly at output levels below capacity. During times of excess capacity, the temptation to cut price to steal business can be high. Moreover, coordination becomes inordinately difficult, because firms will be chasing a moving target. Finally, suppose one firm does cut price in response to a decline in demand. If other firms see the price cut but cannot detect their rival’s volume reduction, they may misread the situation as an effort to steal business.

ASYMMETRIES AMONG FIRMS AND THE SUSTAINABILITY

OF COOPERATIVE PRICES

When firms are not identical, either because they have different costs or are vertically differentiated, achieving cooperative pricing becomes more difficult. When firms are identical, a single monopoly price can be a focal point. However, when firms differ,

Asymmetries among Firms and the Sustainability of Cooperative Prices • 243

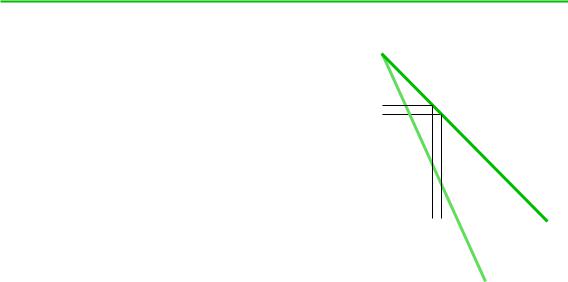

FIGURE 7.2

Monopoly Prices with Asymmetrical Firms

|

P |

|

|

|

|

|

$100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$65 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

$60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

$30 |

|

|

|

|

MCH |

|

|

|

|

||||

$20 |

|

|

|

|

MCL |

|

|

|

|

||||

The low-cost firm’s marginal cost curve is |

|

|

|

|

D |

|

MCL, while the high-cost firm’s marginal cost |

35 40 |

|

|

|

Q |

|

|

|

|

||||

curve is MCH. If the low-cost firm was a |

|

|

(millions of lb |

|||

monopolist, it would set a price of $60. If the |

|

|

per year) |

|||

high-cost firm was a monopolist, it would set |

|

|

MR |

|||

a price of $65. |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

there is no single focal price, and it thus becomes more difficult for firms to coordinate their pricing strategies toward common objectives. Figure 7.2 depicts two firms with different marginal costs and shows that the firm with the lower marginal cost prefers a monopoly price lower than the one with the higher marginal cost.

Even when all firms can agree on the cooperative price, differences in costs, capacities, or product qualities may affect their incentives to abide by the agreement. For example, small firms within a given industry often have more incentive to defect from cooperative pricing than larger firms. One reason is that small firms gain more in new business relative to the loss due to the revenue destruction effect. Another reason, also related to the revenue destruction effect, is that large firms often have weak incentives to punish a smaller price cutter and will instead offer a price umbrella under which the smaller firm can sustain its lower price.

Smaller firms have an additional incentive to lower price on products, including most consumer goods, for which buyers make repeat purchases. A small firm might lower price to induce some consumers to try its product. Once prices are restored to their initial levels, the small firm hopes that some of the consumers who sampled its product will become permanent customers. This strategy will succeed only if there is a lag between the small firm’s price reduction and any response by its larger rivals. Otherwise, few if any new consumers will sample the small firm’s product, and its market share will not increase.

Price Sensitivity of Buyers and the Sustainability

of Cooperative Pricing

A final factor affecting the sustainability of cooperative pricing is the price sensitivity of buyers. When buyers are price sensitive, a firm that undercuts its rivals’ prices by even a small amount may be able to achieve a significant boost in its volume. Under these circumstances, a firm may be tempted to cut price even if it expects that