- •BUSINESSES IN THE BOOK

- •Preface

- •Brief Contents

- •CONTENTS

- •Why Study Strategy?

- •Why Economics?

- •The Need for Principles

- •So What’s the Problem?

- •Firms or Markets?

- •A Framework for Strategy

- •Boundaries of the Firm

- •Market and Competitive Analysis

- •Positioning and Dynamics

- •Internal Organization

- •The Book

- •Endnotes

- •Costs

- •Cost Functions

- •Total Cost Functions

- •Fixed and Variable Costs

- •Average and Marginal Cost Functions

- •The Importance of the Time Period: Long-Run versus Short-Run Cost Functions

- •Sunk versus Avoidable Costs

- •Economic Costs and Profitability

- •Economic versus Accounting Costs

- •Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

- •Demand and Revenues

- •Demand Curve

- •The Price Elasticity of Demand

- •Brand-Level versus Industry-Level Elasticities

- •Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue Functions

- •Theory of the Firm: Pricing and Output Decisions

- •Perfect Competition

- •Game Theory

- •Games in Matrix Form and the Concept of Nash Equilibrium

- •Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Doing Business in 1840

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Doing Business in 1910

- •Business Conditions in 1910: A “Modern” Infrastructure

- •Production Technology

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Government

- •Doing Business Today

- •Modern Infrastructure

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Infrastructure in Emerging Markets

- •Three Different Worlds: Consistent Principles, Changing Conditions, and Adaptive Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Definitions

- •Definition of Economies of Scale

- •Definition of Economies of Scope

- •Economies of Scale Due to Spreading of Product-Specific Fixed Costs

- •Economies of Scale Due to Trade-offs among Alternative Technologies

- •“The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market”

- •Special Sources of Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Density

- •Purchasing

- •Advertising

- •Costs of Sending Messages per Potential Consumer

- •Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

- •Research and Development

- •Physical Properties of Production

- •Inventories

- •Complementarities and Strategic Fit

- •Sources of Diseconomies of Scale

- •Labor Costs and Firm Size

- •Spreading Specialized Resources Too Thin

- •Bureaucracy

- •Economies of Scale: A Summary

- •The Learning Curve

- •The Concept of the Learning Curve

- •Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

- •Learning and Organization

- •The Learning Curve versus Economies of Scale

- •Diversification

- •Why Do Firms Diversify?

- •Efficiency-Based Reasons for Diversification

- •Scope Economies

- •Internal Capital Markets

- •Problematic Justifications for Diversification

- •Diversifying Shareholders’ Portfolios

- •Identifying Undervalued Firms

- •Reasons Not to Diversify

- •Managerial Reasons for Diversification

- •Benefits to Managers from Acquisitions

- •Problems of Corporate Governance

- •The Market for Corporate Control and Recent Changes in Corporate Governance

- •Performance of Diversified Firms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Make versus Buy

- •Upstream, Downstream

- •Defining Boundaries

- •Some Make-or-Buy Fallacies

- •Avoiding Peak Prices

- •Tying Up Channels: Vertical Foreclosure

- •Reasons to “Buy”

- •Exploiting Scale and Learning Economies

- •Bureaucracy Effects: Avoiding Agency and Influence Costs

- •Agency Costs

- •Influence Costs

- •Organizational Design

- •Reasons to “Make”

- •The Economic Foundations of Contracts

- •Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

- •Bounded Rationality

- •Difficulties Specifying or Measuring Performance

- •Asymmetric Information

- •The Role of Contract Law

- •Coordination of Production Flows through the Vertical Chain

- •Leakage of Private Information

- •Transactions Costs

- •Relationship-Specific Assets

- •Forms of Asset Specificity

- •The Fundamental Transformation

- •Rents and Quasi-Rents

- •The Holdup Problem

- •Holdup and Ex Post Cooperation

- •The Holdup Problem and Transactions Costs

- •Contract Negotiation and Renegotiation

- •Investments to Improve Ex Post Bargaining Positions

- •Distrust

- •Reduced Investment

- •Recap: From Relationship-Specific Assets to Transactions Costs

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •What Does It Mean to Be “Integrated?”

- •The Property Rights Theory of the Firm

- •Alternative Forms of Organizing Transactions

- •Governance

- •Delegation

- •Recapping PRT

- •Path Dependence

- •Making the Integration Decision

- •Technical Efficiency versus Agency Efficiency

- •The Technical Efficiency/Agency Efficiency Trade-off

- •Real-World Evidence

- •Double Marginalization: A Final Integration Consideration

- •Alternatives to Vertical Integration

- •Tapered Integration: Make and Buy

- •Franchising

- •Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

- •Implicit Contracts and Long-Term Relationships

- •Business Groups

- •Keiretsu

- •Chaebol

- •Business Groups in Emerging Markets

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitor Identification and Market Definition

- •The Basics of Competitor Identification

- •Example 5.1 The SSNIP in Action: Defining Hospital Markets

- •Putting Competitor Identification into Practice

- •Empirical Approaches to Competitor Identification

- •Geographic Competitor Identification

- •Measuring Market Structure

- •Market Structure and Competition

- •Perfect Competition

- •Many Sellers

- •Homogeneous Products

- •Excess Capacity

- •Monopoly

- •Monopolistic Competition

- •Demand for Differentiated Goods

- •Entry into Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Oligopoly

- •Cournot Quantity Competition

- •The Revenue Destruction Effect

- •Cournot’s Model in Practice

- •Bertrand Price Competition

- •Why Are Cournot and Bertrand Different?

- •Evidence on Market Structure and Performance

- •Price and Concentration

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •6: Entry and Exit

- •Some Facts about Entry and Exit

- •Entry and Exit Decisions: Basic Concepts

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Bain’s Typology of Entry Conditions

- •Analyzing Entry Conditions: The Asymmetry Requirement

- •Structural Entry Barriers

- •Control of Essential Resources

- •Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Marketing Advantages of Incumbency

- •Barriers to Exit

- •Entry-Deterring Strategies

- •Limit Pricing

- •Is Strategic Limit Pricing Rational?

- •Predatory Pricing

- •The Chain-Store Paradox

- •Rescuing Limit Pricing and Predation: The Importance of Uncertainty and Reputation

- •Wars of Attrition

- •Predation and Capacity Expansion

- •Strategic Bundling

- •“Judo Economics”

- •Evidence on Entry-Deterring Behavior

- •Contestable Markets

- •An Entry Deterrence Checklist

- •Entering a New Market

- •Preemptive Entry and Rent Seeking Behavior

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Microdynamics

- •Strategic Commitment

- •Strategic Substitutes and Strategic Complements

- •The Strategic Effect of Commitments

- •Tough and Soft Commitments

- •A Taxonomy of Commitment Strategies

- •The Informational Benefits of Flexibility

- •Real Options

- •Competitive Discipline

- •Dynamic Pricing Rivalry and Tit-for-Tat Pricing

- •Why Is Tit-for-Tat So Compelling?

- •Coordinating on the Right Price

- •Impediments to Coordination

- •The Misread Problem

- •Lumpiness of Orders

- •Information about the Sales Transaction

- •Volatility of Demand Conditions

- •Facilitating Practices

- •Price Leadership

- •Advance Announcement of Price Changes

- •Most Favored Customer Clauses

- •Uniform Delivered Prices

- •Where Does Market Structure Come From?

- •Sutton’s Endogenous Sunk Costs

- •Innovation and Market Evolution

- •Learning and Industry Dynamics

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •8: Industry Analysis

- •Performing a Five-Forces Analysis

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power and Buyer Power

- •Strategies for Coping with the Five Forces

- •Coopetition and the Value Net

- •Applying the Five Forces: Some Industry Analyses

- •Chicago Hospital Markets Then and Now

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Commercial Airframe Manufacturing

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Professional Sports

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Professional Search Firms

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitive Advantage Defined

- •Maximum Willingness-to-Pay and Consumer Surplus

- •From Maximum Willingness-to-Pay to Consumer Surplus

- •Value-Created

- •Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

- •Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

- •Analyzing Value Creation

- •Value Creation and the Value Chain

- •Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

- •Generic Strategies

- •The Strategic Logic of Cost Leadership

- •The Strategic Logic of Benefit Leadership

- •Extracting Profits from Cost and Benefit Advantage

- •Comparing Cost and Benefit Advantages

- •“Stuck in the Middle”

- •Diagnosing Cost and Benefit Drivers

- •Cost Drivers

- •Cost Drivers Related to Firm Size, Scope, and Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Independent of Firm Size, Scope, or Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Related to Organization of the Transactions

- •Benefit Drivers

- •Methods for Estimating and Characterizing Costs and Perceived Benefits

- •Estimating Costs

- •Estimating Benefits

- •Strategic Positioning: Broad Coverage versus Focus Strategies

- •Segmenting an Industry

- •Broad Coverage Strategies

- •Focus Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The “Shopping Problem”

- •Unraveling

- •Alternatives to Disclosure

- •Nonprofit Firms

- •Report Cards

- •Multitasking: Teaching to the Test

- •What to Measure

- •Risk Adjustment

- •Presenting Report Card Results

- •Gaming Report Cards

- •The Certifier Market

- •Certification Bias

- •Matchmaking

- •When Sellers Search for Buyers

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Market Structure and Threats to Sustainability

- •Threats to Sustainability in Competitive and Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Threats to Sustainability under All Market Structures

- •Evidence: The Persistence of Profitability

- •The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Imperfect Mobility and Cospecialization

- •Isolating Mechanisms

- •Impediments to Imitation

- •Legal Restrictions

- •Superior Access to Inputs or Customers

- •The Winner’s Curse

- •Market Size and Scale Economies

- •Intangible Barriers to Imitation

- •Causal Ambiguity

- •Dependence on Historical Circumstances

- •Social Complexity

- •Early-Mover Advantages

- •Learning Curve

- •Reputation and Buyer Uncertainty

- •Buyer Switching Costs

- •Network Effects

- •Networks and Standards

- •Competing “For the Market” versus “In the Market”

- •Knocking off a Dominant Standard

- •Early-Mover Disadvantages

- •Imperfect Imitability and Industry Equilibrium

- •Creating Advantage and Creative Destruction

- •Disruptive Technologies

- •The Productivity Effect

- •The Sunk Cost Effect

- •The Replacement Effect

- •The Efficiency Effect

- •Disruption versus the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Innovation and the Market for Ideas

- •The Environment

- •Factor Conditions

- •Demand Conditions

- •Related Supplier or Support Industries

- •Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Principal–Agent Relationship

- •Combating Agency Problems

- •Performance-Based Incentives

- •Problems with Performance-Based Incentives

- •Preferences over Risky Outcomes

- •Risk Sharing

- •Risk and Incentives

- •Selecting Performance Measures: Managing Trade-offs between Costs

- •Do Pay-for-Performance Incentives Work?

- •Implicit Incentive Contracts

- •Subjective Performance Evaluation

- •Promotion Tournaments

- •Efficiency Wages and the Threat of Termination

- •Incentives in Teams

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •13: Strategy and Structure

- •An Introduction to Structure

- •Individuals, Teams, and Hierarchies

- •Complex Hierarchy

- •Departmentalization

- •Coordination and Control

- •Approaches to Coordination

- •Types of Organizational Structures

- •Functional Structure (U-form)

- •Multidivisional Structure (M-form)

- •Matrix Structure

- •Matrix or Division? A Model of Optimal Structure

- •Network Structure

- •Why Are There So Few Structural Types?

- •Structure—Environment Coherence

- •Technology and Task Interdependence

- •Efficient Information Processing

- •Structure Follows Strategy

- •Strategy, Structure, and the Multinational Firm

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Social Context of Firm Behavior

- •Internal Context

- •Power

- •The Sources of Power

- •Structural Views of Power

- •Do Successful Organizations Need Powerful Managers?

- •The Decision to Allocate Formal Power to Individuals

- •Culture

- •Culture Complements Formal Controls

- •Culture Facilitates Cooperation and Reduces Bargaining Costs

- •Culture, Inertia, and Performance

- •A Word of Caution about Culture

- •External Context, Institutions, and Strategies

- •Institutions and Regulation

- •Interfirm Resource Dependence Relationships

- •Industry Logics: Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Glossary

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

Competitive Advantage and Value Creation: Conceptual Foundations • 299

its sales will slip and its market share will fall. This happened to Lexus and BMW in the early 2010s when its older designs lost share in the large sedan luxury segment to newer high-performance offerings by Audi, Jaguar, and Porsche.

Value-Created

Economic value is created when a producer combines inputs such as labor, capital, raw materials, and purchased components to make a product whose perceived benefit B exceeds the cost C incurred in making the product. The economic value created (or value-created, for short) is thus the difference between the perceived benefit and cost, or B 2 C, where B and C are expressed per unit of the final product.

Value-created must be divided between consumers and producers. Consumer surplus, B 2 P, represents the portion of the value-created that the consumer “captures.” The seller receives the price P and uses it to pay for the inputs that are needed to manufacture the finished product. The producer’s profit margin, P 2 C, represents the portion of the value-created that it captures. Adding together consumer surplus and the producer’s profit gives us the value-created expressed as the sum of consumer surplus and profit:

Value-Created 5 Consumer Surplus 1 Producer Surplus

5(B 2 P) 1 (P 2 C)

5B 2 C

Figure 9.5 depicts value-created for a hypothetical producer of aluminum cans (e.g., a firm such as Crown, Cork and Seal). Start on the left side of the figure. The cost of producing 1,000 aluminum cans is $30 (i.e., C 5 $30). The maximum willingness-to-pay

FIGURE 9.5

The Components of Value-Created in the Market for Aluminum Cans

This is the highest price the buyer (e.g., a softdrink producer) is willing to pay before switching to a substitute product (e.g., tin-plate cans)

|

|

Consumer |

|

Value- |

|

surplus |

|

Consumer’s |

$45 |

|

|

created |

|

||

|

|

||

$70 |

maximum |

|

|

|

willingness |

|

Firm’s |

|

to pay |

|

profit |

|

$100 |

|

$25 |

|

|

|

|

Firm’s cost $30

C |

B – C |

B |

B – P |

P – C |

$ per 1,000 cans

Price (P) = $55

Firm’s cost $30

C

The difference between |

Value created is either . . . |

The sum of |

|

buyer maximum willingness- |

— or — |

consumer surplus |

|

to-pay and cost |

|

and firm profit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

300 • Chapter 9 • Strategic Positioning for Competitive Advantage

EXAMPLE 9.1 THE DIVISION OF THE VALUE-CREATED IN THE SALE OF BEER

AT A BASEBALL GAME

Assigning numbers to the areas in Figure 9.5 is usually difficult because B is hard to measure. But when the product is sold under conditions of monopoly and no reasonable substitutes are available, B can be approximated by making some simplifying assumptions about the nature of the demand curve for the product. An example of a product sold under these circumstances is beer at a baseball game. Because a purchaser of beer would probably not regard soft drinks as a close substitute and because patrons are not allowed to bring in their own beer, the stadium concessionaire has as tight a monopoly on the market as one could imagine.

Here are some basic data on beer sold at Cincinnati Reds baseball games in the late 1980s. The price of a 20-ounce cup of beer was $2.50. The stadium concessionaire, Cincinnati Sports Service, paid the distributor $0.20 per cup for this beer; paid royalties to the city of Cincinnati of $0.24 per cup; paid royalties to

the Cincinnati Reds baseball team of $0.54 per cup; and paid an excise tax of $0.14 per cup. Its total costs were thus $1.12.2

If we assume that the demand curve for beer is linear, then a plausible estimate of consumer surplus that is consistent with the data above is $0.69 per 20-ounce cup of beer.3 Table 9.1 shows the division of value in the sale of the beer using $0.69 per cup as an estimate of consumer surplus.

The brewer clearly captures only a small fraction of the value that is created.4 By contrast, by controlling the concessionaire’s access to the stadium and to the event, the city of Cincinnati and the Cincinnati Reds are able to capture a significant fraction of the value that is created. They can capture value because prospective concessionaires are willing to compete for the right to monopolize this market. As a result, the city and the Reds can extract a significant portion of the monopoly profit that would otherwise flow to the concessionaire.

TABLE 9.1

Division of Value in the Sale of Beer at Riverfront Stadium

Consumer Surplus

$.69

Profit to Cincinnati Sports Service

?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $1.38 Sports Service’s Costs (labor, materials, insurance, etc.)

?

Profit to Cincinnati Reds $.54

Profit to City of Cincinnati $.24

Taxes

$.14

Distributor’s Profit

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $.10 Distributor’s Costs (exclusive of price paid to brewer)

?

Brewer’s Profit

$.30

Brewer’s Costs

$.07

Competitive Advantage and Value Creation: Conceptual Foundations • 301

for a buyer of aluminum cans, for example, a soft-drink bottler such as Coca-Cola Enterprises, is $100 per thousand (i.e., B 5 $100). This represents the highest price the buyer is willing to pay for aluminum cans before switching to the best available alternative product, perhaps plastic containers. The difference between maximum willingness- to-pay and cost is the value-created, which in this case equals $70 (i.e., B 2 C 5 $70). Working our way down the right side of the diagram, we see that value-created of $70 equals the sum of consumer surplus and producer profit. If the seller of aluminum cans charges a price of $55 (i.e., P 5 $55), consumer surplus is $45 per thousand cans (i.e., B 2 P 5 $45), while producer profit margin is $25 per thousand (i.e., P 2 C 5 $25). The price P thus determines how much of the value-created sellers capture as profit and how much buyers capture as consumer surplus.

Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

No product can be viable without creating positive economic value. If B 2 C was negative, there would be no price that consumers would be willing to pay for the product that would cover the cost of the resources that are sacrificed to make the product. Bubblegum-flavored soda, vacuum tubes, and video cassette recorders are products that at one time created positive value, but because of changes in tastes and technology, they no longer create enough benefits to consumers to justify their production.

By contrast, when B 2 C is positive, a firm can profitably purchase inputs from suppliers, convert them into a finished product, and sell it to consumers. When B . C, it will always be possible for an entrepreneur to strike win–win deals with input suppliers and consumers, that is, deals that leave all parties better off than they would be if they did not deal with each other. In economics, win–win trade opportunities are called gains from trade. When B . C, clever entrepreneurs can exploit potential gains from trade.

Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

Although a positive B 2 C is necessary for a product to be economically viable, just because a firm sells a product whose B 2 C is positive is no guarantee that it will make a positive profit. In a market in which entry is easy and all firms create essentially the same economic value, competition between firms will dissipate profitability. Existing firms and new entrants will compete for consumers by bidding down their prices to the point at which all producers earn zero profit. In such markets, consumers capture all the economic value that the product creates.

It follows, then, that in order for a firm to earn positive profit in a competitive industry, the firm must create more economic value than its rivals. That is, the firm must generate a level of B 2 C that its competitors cannot replicate. This simple but powerful insight follows from our earlier discussion of the competitive implications of consumer surplus. To see why, imagine that two sellers are competing for your business. The seller whose product characteristics and price provides you the greatest amount of consumer surplus will win your business. The most aggressive consumer surplus “bid” that either seller would be prepared to offer is the one at which its profit is equal to zero, which occurs when it offers a price P that equals its cost C. At such a bid, a firm would hand over all of the value it creates to you in the form of consumer surplus. The firm with the advantage in this competition is the one that has the highest B 2 C. This is because that firm will be able to win your patronage by offering you a slightly more favorable consumer surplus “bid” than the most aggressive bid its rival is prepared to offer, while retaining the extra value it creates in the form of profit.5

302 • Chapter 9 • Strategic Positioning for Competitive Advantage

In one version of the above competitive scenario, all firms offer identical B. In this case, the “winning” firm must have lower C than its rivals. This reaffirms an idea introduced in Chapter 5, that successful firms in perfectly competitive industries must have lower costs than their rivals. This also holds true in concentrated markets when firms compete aggressively on the basis of price, such as in the Bertrand model also described in Chapter 5. The firm with the lowest cost can slightly undercut its rivals’ prices, capture the entire market, and more than cover its production costs.

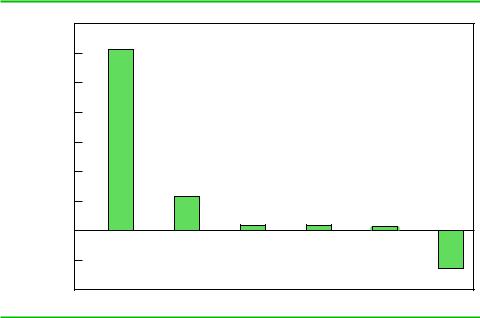

In markets with homogeneous products, the firm offering the highest B 2 C captures the entire market. In most markets, different customers will make different tradeoffs between price and the attributes that drive B, so that one firm might create a higher B 2 C among one segment of consumers, while another firm may create a higher B 2 C among other segments. We saw this, for example, in the personal computer industry in the late 1990s in which Gateway probably created more economic value in the SOHO (small office/home office) segment of the market, while Dell created more economic value in most of the rest of the market. As Figure 9.6 shows, both Dell and Gateway consistently outperformed industry peers during the latter half of the 1990s. We will discuss the implications of this market segmentation later in the chapter.

Analyzing Value Creation

Understanding how a firm’s product creates economic value and whether it can continue to do so is a necessary first step in diagnosing a firm’s potential for achieving a competitive advantage in its market. Diagnosing the sources of value creation requires

FIGURE 9.6

Economic Profitability of Personal Computer Makers

capital |

70.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

60.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

invested |

50.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

40.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

as percentage |

30.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

20.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

profit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Economic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–10.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–20.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gateway |

HP |

IBM |

Compaq |

Apple |

|

|

Dell |

This figure shows average economic profits (expressed as a percentage of invested capital) of selected personal computer makers over the period 1995–1999.

Source: 2000 Stern Stewart Performance 1000 database.

Competitive Advantage and Value Creation: Conceptual Foundations • 303

an understanding of why the firm’s business exists and what its underlying economics are. This, in turn, involves understanding what drives consumer benefits (e.g., how the firm’s products serve consumer needs better than potential substitutes) and what drives costs (e.g., which costs are sensitive to production volume, or how costs change with cumulative experience).

Projecting the firm’s prospects for creating value also involves critically evaluating how the fundamental economic foundations of the business are likely to evolve, an exercise that Richard Rumelt calls consonance analysis.6 Perhaps the most basic of all

EXAMPLE 9.2 KMART VERSUS WAL-MART

Kmart’s battle with Wal-Mart provides a good illustration of a firm’s disadvantage when it has a lower B 2 C than its rivals. Throughout the 1990s, Kmart had invested in technology to support its “Blue Light Special” strategy of frequent but unpredictable sales and promotions. Unfortunately, Kmart had failed to make similar investments in supply-chain information systems, so that the products advertised in newspaper shopping supplements were often out of stock in the stores! During 2001, Kmart attempted to copy Wal-Mart’s “Everyday Low Prices” strategy by cutting prices on 38,000 items while at the same time cutting back on Blue Light Special sales.

Unfortunately for Kmart, this price leadership “strategy” was easy to imitate. In particular, Wal-Mart had no desire to sit idly by and lose share. Besides, Wal-Mart’s unit costs were generally lower than Kmart’s (thanks in part to Wal-Mart’s expertise in supply chain management), so Wal-Mart could (and did) match Kmart’s prices and still remain profitable. To make matters worse for Kmart, there was a WalMart within five miles of most Kmart stores. As a result, Kmart’s strategy merely succeeded in lowering margins without materially affecting its market share. The failure of this strategy contributed to a deterioration in Kmart’s performance in 2001 that eventually led to Kmart’s declaration of bankruptcy in early 2002.

Kmart emerged from bankruptcy in 2003, when a hedge fund led by Edward Lampert bought the company. Lampert promptly shuttered hundreds of stores, laid off thousands of workers, and introduced trendy brands to draw

new customers. In 2005, when Kmart acquired Sears Roebuck, Lampert was touted as the savior of the old-line mass merchandisers. It hasn’t worked out that way.

In the wake of the merger, Lampert converted many Kmart stores in the United States and Canada to Sears outlets. At the same time, Kmart attempted to reposition itself as the “store of the neighborhood.” This strategy aimed primarily at racial or ethnic communities in urban areas, most especially African Americans and Hispanics. The goal of the strategy seemed to be to differentiate Kmart from Wal-Mart and Target by further exaggerating the income differential between Kmart shoppers and shoppers at Wal-Mart and Target.7 However, this strategy brought Kmart into more direct competition with deepdiscount “dollar retailers,” such as Dollar General and Family Dollar, that have been targeting lower income urban communities for many years. Thanks to the end of the property bubble, Sears has even suffered major losses in real estate, which represents as much as one half of the value of the company (based on the revenues that could be generated if Sears sold the land on which its stores sit).

Nearly a decade after Lampert rode in on his white horse to rescue Kmart and Sears, the two retailers continue to struggle. Although Lampert has been hailed as the “next Warren Buffett,” he has thus far failed to undo the stores’ B 2 C disadvantage. Although most analysts believe that Sears is unlikely to return to its former glory, investors remain enamored of Lampert and Sears stock continues to hold its own.