- •BUSINESSES IN THE BOOK

- •Preface

- •Brief Contents

- •CONTENTS

- •Why Study Strategy?

- •Why Economics?

- •The Need for Principles

- •So What’s the Problem?

- •Firms or Markets?

- •A Framework for Strategy

- •Boundaries of the Firm

- •Market and Competitive Analysis

- •Positioning and Dynamics

- •Internal Organization

- •The Book

- •Endnotes

- •Costs

- •Cost Functions

- •Total Cost Functions

- •Fixed and Variable Costs

- •Average and Marginal Cost Functions

- •The Importance of the Time Period: Long-Run versus Short-Run Cost Functions

- •Sunk versus Avoidable Costs

- •Economic Costs and Profitability

- •Economic versus Accounting Costs

- •Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

- •Demand and Revenues

- •Demand Curve

- •The Price Elasticity of Demand

- •Brand-Level versus Industry-Level Elasticities

- •Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue Functions

- •Theory of the Firm: Pricing and Output Decisions

- •Perfect Competition

- •Game Theory

- •Games in Matrix Form and the Concept of Nash Equilibrium

- •Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Doing Business in 1840

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Doing Business in 1910

- •Business Conditions in 1910: A “Modern” Infrastructure

- •Production Technology

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Government

- •Doing Business Today

- •Modern Infrastructure

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Infrastructure in Emerging Markets

- •Three Different Worlds: Consistent Principles, Changing Conditions, and Adaptive Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Definitions

- •Definition of Economies of Scale

- •Definition of Economies of Scope

- •Economies of Scale Due to Spreading of Product-Specific Fixed Costs

- •Economies of Scale Due to Trade-offs among Alternative Technologies

- •“The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market”

- •Special Sources of Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Density

- •Purchasing

- •Advertising

- •Costs of Sending Messages per Potential Consumer

- •Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

- •Research and Development

- •Physical Properties of Production

- •Inventories

- •Complementarities and Strategic Fit

- •Sources of Diseconomies of Scale

- •Labor Costs and Firm Size

- •Spreading Specialized Resources Too Thin

- •Bureaucracy

- •Economies of Scale: A Summary

- •The Learning Curve

- •The Concept of the Learning Curve

- •Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

- •Learning and Organization

- •The Learning Curve versus Economies of Scale

- •Diversification

- •Why Do Firms Diversify?

- •Efficiency-Based Reasons for Diversification

- •Scope Economies

- •Internal Capital Markets

- •Problematic Justifications for Diversification

- •Diversifying Shareholders’ Portfolios

- •Identifying Undervalued Firms

- •Reasons Not to Diversify

- •Managerial Reasons for Diversification

- •Benefits to Managers from Acquisitions

- •Problems of Corporate Governance

- •The Market for Corporate Control and Recent Changes in Corporate Governance

- •Performance of Diversified Firms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Make versus Buy

- •Upstream, Downstream

- •Defining Boundaries

- •Some Make-or-Buy Fallacies

- •Avoiding Peak Prices

- •Tying Up Channels: Vertical Foreclosure

- •Reasons to “Buy”

- •Exploiting Scale and Learning Economies

- •Bureaucracy Effects: Avoiding Agency and Influence Costs

- •Agency Costs

- •Influence Costs

- •Organizational Design

- •Reasons to “Make”

- •The Economic Foundations of Contracts

- •Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

- •Bounded Rationality

- •Difficulties Specifying or Measuring Performance

- •Asymmetric Information

- •The Role of Contract Law

- •Coordination of Production Flows through the Vertical Chain

- •Leakage of Private Information

- •Transactions Costs

- •Relationship-Specific Assets

- •Forms of Asset Specificity

- •The Fundamental Transformation

- •Rents and Quasi-Rents

- •The Holdup Problem

- •Holdup and Ex Post Cooperation

- •The Holdup Problem and Transactions Costs

- •Contract Negotiation and Renegotiation

- •Investments to Improve Ex Post Bargaining Positions

- •Distrust

- •Reduced Investment

- •Recap: From Relationship-Specific Assets to Transactions Costs

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •What Does It Mean to Be “Integrated?”

- •The Property Rights Theory of the Firm

- •Alternative Forms of Organizing Transactions

- •Governance

- •Delegation

- •Recapping PRT

- •Path Dependence

- •Making the Integration Decision

- •Technical Efficiency versus Agency Efficiency

- •The Technical Efficiency/Agency Efficiency Trade-off

- •Real-World Evidence

- •Double Marginalization: A Final Integration Consideration

- •Alternatives to Vertical Integration

- •Tapered Integration: Make and Buy

- •Franchising

- •Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

- •Implicit Contracts and Long-Term Relationships

- •Business Groups

- •Keiretsu

- •Chaebol

- •Business Groups in Emerging Markets

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitor Identification and Market Definition

- •The Basics of Competitor Identification

- •Example 5.1 The SSNIP in Action: Defining Hospital Markets

- •Putting Competitor Identification into Practice

- •Empirical Approaches to Competitor Identification

- •Geographic Competitor Identification

- •Measuring Market Structure

- •Market Structure and Competition

- •Perfect Competition

- •Many Sellers

- •Homogeneous Products

- •Excess Capacity

- •Monopoly

- •Monopolistic Competition

- •Demand for Differentiated Goods

- •Entry into Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Oligopoly

- •Cournot Quantity Competition

- •The Revenue Destruction Effect

- •Cournot’s Model in Practice

- •Bertrand Price Competition

- •Why Are Cournot and Bertrand Different?

- •Evidence on Market Structure and Performance

- •Price and Concentration

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •6: Entry and Exit

- •Some Facts about Entry and Exit

- •Entry and Exit Decisions: Basic Concepts

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Bain’s Typology of Entry Conditions

- •Analyzing Entry Conditions: The Asymmetry Requirement

- •Structural Entry Barriers

- •Control of Essential Resources

- •Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Marketing Advantages of Incumbency

- •Barriers to Exit

- •Entry-Deterring Strategies

- •Limit Pricing

- •Is Strategic Limit Pricing Rational?

- •Predatory Pricing

- •The Chain-Store Paradox

- •Rescuing Limit Pricing and Predation: The Importance of Uncertainty and Reputation

- •Wars of Attrition

- •Predation and Capacity Expansion

- •Strategic Bundling

- •“Judo Economics”

- •Evidence on Entry-Deterring Behavior

- •Contestable Markets

- •An Entry Deterrence Checklist

- •Entering a New Market

- •Preemptive Entry and Rent Seeking Behavior

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Microdynamics

- •Strategic Commitment

- •Strategic Substitutes and Strategic Complements

- •The Strategic Effect of Commitments

- •Tough and Soft Commitments

- •A Taxonomy of Commitment Strategies

- •The Informational Benefits of Flexibility

- •Real Options

- •Competitive Discipline

- •Dynamic Pricing Rivalry and Tit-for-Tat Pricing

- •Why Is Tit-for-Tat So Compelling?

- •Coordinating on the Right Price

- •Impediments to Coordination

- •The Misread Problem

- •Lumpiness of Orders

- •Information about the Sales Transaction

- •Volatility of Demand Conditions

- •Facilitating Practices

- •Price Leadership

- •Advance Announcement of Price Changes

- •Most Favored Customer Clauses

- •Uniform Delivered Prices

- •Where Does Market Structure Come From?

- •Sutton’s Endogenous Sunk Costs

- •Innovation and Market Evolution

- •Learning and Industry Dynamics

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •8: Industry Analysis

- •Performing a Five-Forces Analysis

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power and Buyer Power

- •Strategies for Coping with the Five Forces

- •Coopetition and the Value Net

- •Applying the Five Forces: Some Industry Analyses

- •Chicago Hospital Markets Then and Now

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Commercial Airframe Manufacturing

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Professional Sports

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Professional Search Firms

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitive Advantage Defined

- •Maximum Willingness-to-Pay and Consumer Surplus

- •From Maximum Willingness-to-Pay to Consumer Surplus

- •Value-Created

- •Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

- •Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

- •Analyzing Value Creation

- •Value Creation and the Value Chain

- •Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

- •Generic Strategies

- •The Strategic Logic of Cost Leadership

- •The Strategic Logic of Benefit Leadership

- •Extracting Profits from Cost and Benefit Advantage

- •Comparing Cost and Benefit Advantages

- •“Stuck in the Middle”

- •Diagnosing Cost and Benefit Drivers

- •Cost Drivers

- •Cost Drivers Related to Firm Size, Scope, and Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Independent of Firm Size, Scope, or Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Related to Organization of the Transactions

- •Benefit Drivers

- •Methods for Estimating and Characterizing Costs and Perceived Benefits

- •Estimating Costs

- •Estimating Benefits

- •Strategic Positioning: Broad Coverage versus Focus Strategies

- •Segmenting an Industry

- •Broad Coverage Strategies

- •Focus Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The “Shopping Problem”

- •Unraveling

- •Alternatives to Disclosure

- •Nonprofit Firms

- •Report Cards

- •Multitasking: Teaching to the Test

- •What to Measure

- •Risk Adjustment

- •Presenting Report Card Results

- •Gaming Report Cards

- •The Certifier Market

- •Certification Bias

- •Matchmaking

- •When Sellers Search for Buyers

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Market Structure and Threats to Sustainability

- •Threats to Sustainability in Competitive and Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Threats to Sustainability under All Market Structures

- •Evidence: The Persistence of Profitability

- •The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Imperfect Mobility and Cospecialization

- •Isolating Mechanisms

- •Impediments to Imitation

- •Legal Restrictions

- •Superior Access to Inputs or Customers

- •The Winner’s Curse

- •Market Size and Scale Economies

- •Intangible Barriers to Imitation

- •Causal Ambiguity

- •Dependence on Historical Circumstances

- •Social Complexity

- •Early-Mover Advantages

- •Learning Curve

- •Reputation and Buyer Uncertainty

- •Buyer Switching Costs

- •Network Effects

- •Networks and Standards

- •Competing “For the Market” versus “In the Market”

- •Knocking off a Dominant Standard

- •Early-Mover Disadvantages

- •Imperfect Imitability and Industry Equilibrium

- •Creating Advantage and Creative Destruction

- •Disruptive Technologies

- •The Productivity Effect

- •The Sunk Cost Effect

- •The Replacement Effect

- •The Efficiency Effect

- •Disruption versus the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Innovation and the Market for Ideas

- •The Environment

- •Factor Conditions

- •Demand Conditions

- •Related Supplier or Support Industries

- •Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Principal–Agent Relationship

- •Combating Agency Problems

- •Performance-Based Incentives

- •Problems with Performance-Based Incentives

- •Preferences over Risky Outcomes

- •Risk Sharing

- •Risk and Incentives

- •Selecting Performance Measures: Managing Trade-offs between Costs

- •Do Pay-for-Performance Incentives Work?

- •Implicit Incentive Contracts

- •Subjective Performance Evaluation

- •Promotion Tournaments

- •Efficiency Wages and the Threat of Termination

- •Incentives in Teams

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •13: Strategy and Structure

- •An Introduction to Structure

- •Individuals, Teams, and Hierarchies

- •Complex Hierarchy

- •Departmentalization

- •Coordination and Control

- •Approaches to Coordination

- •Types of Organizational Structures

- •Functional Structure (U-form)

- •Multidivisional Structure (M-form)

- •Matrix Structure

- •Matrix or Division? A Model of Optimal Structure

- •Network Structure

- •Why Are There So Few Structural Types?

- •Structure—Environment Coherence

- •Technology and Task Interdependence

- •Efficient Information Processing

- •Structure Follows Strategy

- •Strategy, Structure, and the Multinational Firm

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Social Context of Firm Behavior

- •Internal Context

- •Power

- •The Sources of Power

- •Structural Views of Power

- •Do Successful Organizations Need Powerful Managers?

- •The Decision to Allocate Formal Power to Individuals

- •Culture

- •Culture Complements Formal Controls

- •Culture Facilitates Cooperation and Reduces Bargaining Costs

- •Culture, Inertia, and Performance

- •A Word of Caution about Culture

- •External Context, Institutions, and Strategies

- •Institutions and Regulation

- •Interfirm Resource Dependence Relationships

- •Industry Logics: Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Glossary

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

154 • Chapter 4 • Integration and Its Alternatives

Business Groups

For much of the past half century, Japanese and South Korean firms did not organize the vertical chain through arm’s-length contracts, vertical integration, or joint ventures. Nor did they rely on the trust that characterizes implicit contracts. Instead, they relied on a labyrinth of long-term, semiformal relationships between firms up and down the vertical chain. These multinational business groups, known in Japan as keiretsu and in South Korea as chaebol, were often held up as exemplars of organizational design, not just for businesses in developing nations, but for all businesses. Today, the keiretsu seem to have withered away while the chaebol no longer enjoy enviable rates of growth and profitability. Even so, giant business groups in developing markets are once again getting the attention of business strategists.

Keiretsu

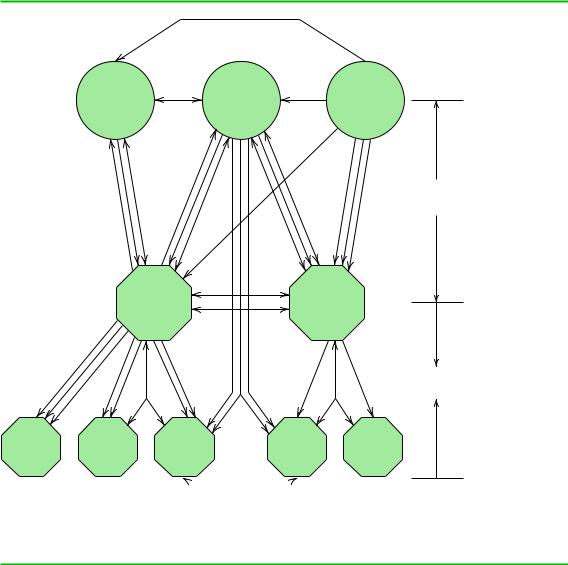

Ever since the 1960s, business strategists have alternately admired and criticized Japanese keiretsu. It has always been difficult for outsiders to decipher the exact structure of keiretsu. They involved a complex and fluid web of formalized institutional linkages, as depicted in Figure 4.3. Based on data on banking patterns, corporate board memberships, and social affiliations such as executive “lunch clubs,” analysts identified six large keiretsu—Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, DKB, Mitsui, Fuyo, and Sanwa. At their peak, each had more than 80 member firms. All keiretsu had core banks that facilitate relationships among members, and nearly all had members in key industries such as steel, life insurance, and chemicals. Loose accounting standards allowed members to hide assets and liabilities in each other so as to lower taxes. It is generally thought that each member of a keiretsu was the first choice of another keiretsu member in all business dealings. Research suggested that this was especially true in vertical relationships involving complex and highly specific parts, as supported by Williamsonian economics.18 This formalization of vertical and horizontal relationships was to be one of the reasons Japanese corporations outperformed U.S. corporations during the crucial period of 1970–1990. It is difficult to overstate the extent to which some U.S. business strategists encouraged American companies to emulate the keiretsu.

Not all business strategists were so sanguine. A major concern was that the keiretsu benefited poor-performing members at the expense of more profitable partners, in much the same way that successful divisions in Western conglomerates often crosssubsidize struggling divisions. This was usually done informally in the keiretsu, for example, by paying inflated fees to inefficient suppliers. During the 1990s, government ministries often intervened by requiring healthier members to pay a “tax” to their struggling keiretsu brethren. Regardless of the mechanism, these cross-subsidies served to buttress members against the risk of failure at the expense of promoting efficiency. Moreover, such risk sharing ran counter to the interests of investors, who could avoid risk by diversifying their portfolios. Thus, even though firms in the keiretsu remained independent, they did not face the same hard-edged incentives that normally favor arm’s-length transactions.

The close ties between banks and manufacturers helped the keiretsu respond quickly to growth opportunities after World War II. Sustained growth of the Japanese postwar economy ensured that the keiretsu would thrive, and close relationships among trading partners allowed them to develop high-quality products in complex manufacturing environments such as automobiles and electronics. But Western manufacturers eventually caught up, and the economic downturn that resulted from the bursting of the Japanese real estate bubble in the early 1990s meant that keiretsu

Alternatives to Vertical Integration • 155

FIGURE 4.3

Debt, Equity, And Trade Linkages In Japanese KEIRETSU

Other |

|

Life |

financial |

Banks |

insurance |

institutions |

|

companies |

Intermarket

keiretsu

Trading |

Manu- |

|

facturing |

||

companies |

||

companies |

||

|

Vertical

keiretsu

Satellite

Satellite  companies

companies

Equity shareholdings

Equity shareholdings

Loans

Loans

Trade (supplies, finished goods, bank deposits, life insurance policies)

Trade (supplies, finished goods, bank deposits, life insurance policies)

The dashed lines show equity holdings within a typical keiretsu, the solid lines show loans, and the small dashed lines show the patterns of exchange within the keiretsu.

Source: Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business School Press. From Gerlach, M. L., and J. Lincoln, “The Organization of Business Networks in the United States and Japan,” in Nohria, N. and R. G. Eccles (eds.), 1994,

Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, p. 494.

firms were no longer insulated from macroeconomic conditions. At the same time, the downturn forced the consolidation of banks, followed by consolidation of other industrial members. These unwieldy giants struggled to maintain their close relationships. The last straw may have been changes in accounting rules that had previously favored the keiretsu. By the late 1990s, the ties among keiretsu members were fraying; even

156 • Chapter 4 • Integration and Its Alternatives

firms that shared the same corporate name, for example, Mitsubishi Automobiles and Mitsubishi Electronics, were no longer closely linked. When Nissan’s new CEO Carlos Ghosn dismantled the automaker’s supply keiretsu in the early 2000s, some Japanese questioned whether this “outsider” understood Japanese culture. But by the end of the decade, Honda and Toyota had also decentralized their supply chains. The traditional keiretsu were finished.

Recent research by Yoshior Miwa and J. Mark Ramseyer cast doubt on whether keiretsu ever existed.19 Miwa and Ramseyer observe that executives at firms in a given keiretsu belonged to the same lunch clubs and met at other business events, but their business relationships were otherwise quite ordinary. Member firms borrowed substantial amounts from their keiretsu’s central bank, but they borrowed nearly as much from other banks. They went outside of the keiretsu for other business dealings as well. Miwa and Ramseyer show that keiretsu profits were never exceptional. Based on this and other data, Miwa and Ramseyer conclude that the tight-knit and highly profitable structure of the Japanese keiretsu is a myth that was perpetuated for 40 years.

Chaebol

Just as the keiretsu enjoyed rapid growth in post–World War II Japan, South Korea’s chaebol enjoyed rapid growth after the Korean War, especially after 1961. Chaebol are more varied in structure than keiretsu; some feature close relations among independent firms, but the best known—LG, Hyundai, and Samsung—are centralized and controlled by family groups. This assures even closer coordination and investment in specific assets, but also intensifies the drawbacks of integration. The only midsize businesses to thrive in Korea seem to be those that partner with a chaebol. Chaebol have not been as closely studied as keiretsu, and it is not clear whether their success is due to the close ties among members or reflects broader macroeconomic conditions in South Korea, which enjoys a unique mix of a highly trained but relatively low paid labor force. This has always allowed chaebol firms to be rapid second movers in technology markets such as cellular phones, but as the pace of innovation has increased, chaebol firms seem to be at a disadvantage. Consider the iPhone and the Blackberry, which left Samsung lagging far behind.

Business Groups in Emerging Markets

Widely diversified multinational business groups in emerging markets seem to be taking the world by storm. Along with well-known Japanese and Korean groups like those of Matsushita and Hyundai, strategists are buzzing about Alfa in Mexico, Koc Holding in Turkey, and The Votorantim Group in Brazil. Through his holdings in the Grupo Carso SAB, Mexico’s Carlos Slim Helu has become the wealthiest person in the world.

The model for these new business groups may be India’s Tata Group. Nearly a century and a half old, Tata businesses have been operating in India since 1868. The family-run group, under the leadership of Ratan Tata since 1991, is India’s largest private-sector employer, with 350,000 employees, of which 30 percent work outside of India. It is also India’s largest business group, with 2008 revenues of $63 billion. While Tata is the best known group, there are other Indian groups that are very large and possess global capabilities, such as the Aditya Birla group with its Hindalco subsidiary, one of the top five global aluminum firms.

Tata is large and diverse. If it were publicly traded, Tata would be a Global Fortune 500 member. And its penchant for massive horizontal diversification is impressive,

Alternatives to Vertical Integration • 157

even among emerging market business groups. Tata operates 98 companies in seven sectors—engineering, materials, IT, consumer products, energy, chemicals, and services. Tata’s two largest businesses are steel and telecommunications. Tata is also big in automobiles, salt, watches, hotels, and artificial limbs and has used its size to finance acquisitions of famous global brands including Jaguar, Daewoo, and Tetley Tea. The favorable financial environment prevailing in India, at least until 2008, has likely contributed to Tata’s preference for mergers and acquisitions over alliances. Given that the research evidence (described in Chapter 2) is not kind to unrelated diversification, it is somewhat difficult at first to explain the success of Tata and the rest of these business groups.

Business groups have been evolving as a result of policy and regulatory changes to promote more competitive markets. This has taken place in China since the reforms of Deng Xiao Ping began in 1978 and in India since the regulatory reforms that began 1991. As the growth rate in these countries accelerated to double that of Western economies, business groups have adjusted to these reforms and have innovated their structures and operations in ways that make them much more competitive than their level of horizontal diversification might suggest.

Large groups like Tata have centralized corporate control and enhanced corporate oversight, often supported by efforts to promote a corporate culture and a group code of ethics, with the result that the group is less of a holding company than its business mix might suggest. This control and advisory function is supported by the internal consulting capabilities of Tata Consulting and is complemented by extensive training and exposure to headquarters culture provided in India to the managers of all businesses acquired by the group throughout the world. Groups with such controls can sometimes take advantage of their tight governance in ways that would be predicted by economic principles of value creation. In Tata, for instance, Tata Consulting, Tata Chemicals, and Titan Industries (a Tata subsidiary) worked together to produce the world’s cheapest water purifier. Business groups that have not invested in highpowered corporate control can exercise some influence over subsidiaries by instituting corporate board oversight (often involving “interlocks,” in which firms’ executives serve on each other’s boards) and by transferring profits among subsidiaries. However, these activities do not substitute for direct oversight.

These business groups may also take advantage of their close ties to national governments, which provide a favorable regulatory environment. It is not clear whether this reflects government desires to develop prestigious global businesses or whether it merely reflects corruption, as was suggested by some when Tata chairman Ratan Tata was caught on tape conversing with an allegedly corrupt lobbyist. While India has somewhat of a tradition of corruption, as typified in the period of the “License Raj” from the end of British rule until 1980, business group managers today argue that times have changed and economic rules have been reformed. This change is evidenced by the success of Tata and other groups in expanding in overseas and especially Western markets, which would not be possible if their advantage stemmed from corruption.

One of the biggest advantages enjoyed by business groups in India and China is their access to cheap local labor. But this advantage comes at a cost—the same regions that offer a surplus of cheap labor tend to have a scarce supply of well-trained managers. The most successful business groups solve this problem by relying on an internal market for management talent. The groups train their own managers, identify the ones with the most talent, and match them to the toughest and most important management positions—a significant investment for a group. This combination of low-cost labor