- •BUSINESSES IN THE BOOK

- •Preface

- •Brief Contents

- •CONTENTS

- •Why Study Strategy?

- •Why Economics?

- •The Need for Principles

- •So What’s the Problem?

- •Firms or Markets?

- •A Framework for Strategy

- •Boundaries of the Firm

- •Market and Competitive Analysis

- •Positioning and Dynamics

- •Internal Organization

- •The Book

- •Endnotes

- •Costs

- •Cost Functions

- •Total Cost Functions

- •Fixed and Variable Costs

- •Average and Marginal Cost Functions

- •The Importance of the Time Period: Long-Run versus Short-Run Cost Functions

- •Sunk versus Avoidable Costs

- •Economic Costs and Profitability

- •Economic versus Accounting Costs

- •Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

- •Demand and Revenues

- •Demand Curve

- •The Price Elasticity of Demand

- •Brand-Level versus Industry-Level Elasticities

- •Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue Functions

- •Theory of the Firm: Pricing and Output Decisions

- •Perfect Competition

- •Game Theory

- •Games in Matrix Form and the Concept of Nash Equilibrium

- •Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Doing Business in 1840

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Doing Business in 1910

- •Business Conditions in 1910: A “Modern” Infrastructure

- •Production Technology

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Government

- •Doing Business Today

- •Modern Infrastructure

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Infrastructure in Emerging Markets

- •Three Different Worlds: Consistent Principles, Changing Conditions, and Adaptive Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Definitions

- •Definition of Economies of Scale

- •Definition of Economies of Scope

- •Economies of Scale Due to Spreading of Product-Specific Fixed Costs

- •Economies of Scale Due to Trade-offs among Alternative Technologies

- •“The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market”

- •Special Sources of Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Density

- •Purchasing

- •Advertising

- •Costs of Sending Messages per Potential Consumer

- •Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

- •Research and Development

- •Physical Properties of Production

- •Inventories

- •Complementarities and Strategic Fit

- •Sources of Diseconomies of Scale

- •Labor Costs and Firm Size

- •Spreading Specialized Resources Too Thin

- •Bureaucracy

- •Economies of Scale: A Summary

- •The Learning Curve

- •The Concept of the Learning Curve

- •Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

- •Learning and Organization

- •The Learning Curve versus Economies of Scale

- •Diversification

- •Why Do Firms Diversify?

- •Efficiency-Based Reasons for Diversification

- •Scope Economies

- •Internal Capital Markets

- •Problematic Justifications for Diversification

- •Diversifying Shareholders’ Portfolios

- •Identifying Undervalued Firms

- •Reasons Not to Diversify

- •Managerial Reasons for Diversification

- •Benefits to Managers from Acquisitions

- •Problems of Corporate Governance

- •The Market for Corporate Control and Recent Changes in Corporate Governance

- •Performance of Diversified Firms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Make versus Buy

- •Upstream, Downstream

- •Defining Boundaries

- •Some Make-or-Buy Fallacies

- •Avoiding Peak Prices

- •Tying Up Channels: Vertical Foreclosure

- •Reasons to “Buy”

- •Exploiting Scale and Learning Economies

- •Bureaucracy Effects: Avoiding Agency and Influence Costs

- •Agency Costs

- •Influence Costs

- •Organizational Design

- •Reasons to “Make”

- •The Economic Foundations of Contracts

- •Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

- •Bounded Rationality

- •Difficulties Specifying or Measuring Performance

- •Asymmetric Information

- •The Role of Contract Law

- •Coordination of Production Flows through the Vertical Chain

- •Leakage of Private Information

- •Transactions Costs

- •Relationship-Specific Assets

- •Forms of Asset Specificity

- •The Fundamental Transformation

- •Rents and Quasi-Rents

- •The Holdup Problem

- •Holdup and Ex Post Cooperation

- •The Holdup Problem and Transactions Costs

- •Contract Negotiation and Renegotiation

- •Investments to Improve Ex Post Bargaining Positions

- •Distrust

- •Reduced Investment

- •Recap: From Relationship-Specific Assets to Transactions Costs

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •What Does It Mean to Be “Integrated?”

- •The Property Rights Theory of the Firm

- •Alternative Forms of Organizing Transactions

- •Governance

- •Delegation

- •Recapping PRT

- •Path Dependence

- •Making the Integration Decision

- •Technical Efficiency versus Agency Efficiency

- •The Technical Efficiency/Agency Efficiency Trade-off

- •Real-World Evidence

- •Double Marginalization: A Final Integration Consideration

- •Alternatives to Vertical Integration

- •Tapered Integration: Make and Buy

- •Franchising

- •Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

- •Implicit Contracts and Long-Term Relationships

- •Business Groups

- •Keiretsu

- •Chaebol

- •Business Groups in Emerging Markets

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitor Identification and Market Definition

- •The Basics of Competitor Identification

- •Example 5.1 The SSNIP in Action: Defining Hospital Markets

- •Putting Competitor Identification into Practice

- •Empirical Approaches to Competitor Identification

- •Geographic Competitor Identification

- •Measuring Market Structure

- •Market Structure and Competition

- •Perfect Competition

- •Many Sellers

- •Homogeneous Products

- •Excess Capacity

- •Monopoly

- •Monopolistic Competition

- •Demand for Differentiated Goods

- •Entry into Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Oligopoly

- •Cournot Quantity Competition

- •The Revenue Destruction Effect

- •Cournot’s Model in Practice

- •Bertrand Price Competition

- •Why Are Cournot and Bertrand Different?

- •Evidence on Market Structure and Performance

- •Price and Concentration

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •6: Entry and Exit

- •Some Facts about Entry and Exit

- •Entry and Exit Decisions: Basic Concepts

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Bain’s Typology of Entry Conditions

- •Analyzing Entry Conditions: The Asymmetry Requirement

- •Structural Entry Barriers

- •Control of Essential Resources

- •Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Marketing Advantages of Incumbency

- •Barriers to Exit

- •Entry-Deterring Strategies

- •Limit Pricing

- •Is Strategic Limit Pricing Rational?

- •Predatory Pricing

- •The Chain-Store Paradox

- •Rescuing Limit Pricing and Predation: The Importance of Uncertainty and Reputation

- •Wars of Attrition

- •Predation and Capacity Expansion

- •Strategic Bundling

- •“Judo Economics”

- •Evidence on Entry-Deterring Behavior

- •Contestable Markets

- •An Entry Deterrence Checklist

- •Entering a New Market

- •Preemptive Entry and Rent Seeking Behavior

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Microdynamics

- •Strategic Commitment

- •Strategic Substitutes and Strategic Complements

- •The Strategic Effect of Commitments

- •Tough and Soft Commitments

- •A Taxonomy of Commitment Strategies

- •The Informational Benefits of Flexibility

- •Real Options

- •Competitive Discipline

- •Dynamic Pricing Rivalry and Tit-for-Tat Pricing

- •Why Is Tit-for-Tat So Compelling?

- •Coordinating on the Right Price

- •Impediments to Coordination

- •The Misread Problem

- •Lumpiness of Orders

- •Information about the Sales Transaction

- •Volatility of Demand Conditions

- •Facilitating Practices

- •Price Leadership

- •Advance Announcement of Price Changes

- •Most Favored Customer Clauses

- •Uniform Delivered Prices

- •Where Does Market Structure Come From?

- •Sutton’s Endogenous Sunk Costs

- •Innovation and Market Evolution

- •Learning and Industry Dynamics

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •8: Industry Analysis

- •Performing a Five-Forces Analysis

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power and Buyer Power

- •Strategies for Coping with the Five Forces

- •Coopetition and the Value Net

- •Applying the Five Forces: Some Industry Analyses

- •Chicago Hospital Markets Then and Now

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Commercial Airframe Manufacturing

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Professional Sports

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Professional Search Firms

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitive Advantage Defined

- •Maximum Willingness-to-Pay and Consumer Surplus

- •From Maximum Willingness-to-Pay to Consumer Surplus

- •Value-Created

- •Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

- •Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

- •Analyzing Value Creation

- •Value Creation and the Value Chain

- •Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

- •Generic Strategies

- •The Strategic Logic of Cost Leadership

- •The Strategic Logic of Benefit Leadership

- •Extracting Profits from Cost and Benefit Advantage

- •Comparing Cost and Benefit Advantages

- •“Stuck in the Middle”

- •Diagnosing Cost and Benefit Drivers

- •Cost Drivers

- •Cost Drivers Related to Firm Size, Scope, and Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Independent of Firm Size, Scope, or Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Related to Organization of the Transactions

- •Benefit Drivers

- •Methods for Estimating and Characterizing Costs and Perceived Benefits

- •Estimating Costs

- •Estimating Benefits

- •Strategic Positioning: Broad Coverage versus Focus Strategies

- •Segmenting an Industry

- •Broad Coverage Strategies

- •Focus Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The “Shopping Problem”

- •Unraveling

- •Alternatives to Disclosure

- •Nonprofit Firms

- •Report Cards

- •Multitasking: Teaching to the Test

- •What to Measure

- •Risk Adjustment

- •Presenting Report Card Results

- •Gaming Report Cards

- •The Certifier Market

- •Certification Bias

- •Matchmaking

- •When Sellers Search for Buyers

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Market Structure and Threats to Sustainability

- •Threats to Sustainability in Competitive and Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Threats to Sustainability under All Market Structures

- •Evidence: The Persistence of Profitability

- •The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Imperfect Mobility and Cospecialization

- •Isolating Mechanisms

- •Impediments to Imitation

- •Legal Restrictions

- •Superior Access to Inputs or Customers

- •The Winner’s Curse

- •Market Size and Scale Economies

- •Intangible Barriers to Imitation

- •Causal Ambiguity

- •Dependence on Historical Circumstances

- •Social Complexity

- •Early-Mover Advantages

- •Learning Curve

- •Reputation and Buyer Uncertainty

- •Buyer Switching Costs

- •Network Effects

- •Networks and Standards

- •Competing “For the Market” versus “In the Market”

- •Knocking off a Dominant Standard

- •Early-Mover Disadvantages

- •Imperfect Imitability and Industry Equilibrium

- •Creating Advantage and Creative Destruction

- •Disruptive Technologies

- •The Productivity Effect

- •The Sunk Cost Effect

- •The Replacement Effect

- •The Efficiency Effect

- •Disruption versus the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Innovation and the Market for Ideas

- •The Environment

- •Factor Conditions

- •Demand Conditions

- •Related Supplier or Support Industries

- •Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Principal–Agent Relationship

- •Combating Agency Problems

- •Performance-Based Incentives

- •Problems with Performance-Based Incentives

- •Preferences over Risky Outcomes

- •Risk Sharing

- •Risk and Incentives

- •Selecting Performance Measures: Managing Trade-offs between Costs

- •Do Pay-for-Performance Incentives Work?

- •Implicit Incentive Contracts

- •Subjective Performance Evaluation

- •Promotion Tournaments

- •Efficiency Wages and the Threat of Termination

- •Incentives in Teams

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •13: Strategy and Structure

- •An Introduction to Structure

- •Individuals, Teams, and Hierarchies

- •Complex Hierarchy

- •Departmentalization

- •Coordination and Control

- •Approaches to Coordination

- •Types of Organizational Structures

- •Functional Structure (U-form)

- •Multidivisional Structure (M-form)

- •Matrix Structure

- •Matrix or Division? A Model of Optimal Structure

- •Network Structure

- •Why Are There So Few Structural Types?

- •Structure—Environment Coherence

- •Technology and Task Interdependence

- •Efficient Information Processing

- •Structure Follows Strategy

- •Strategy, Structure, and the Multinational Firm

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Social Context of Firm Behavior

- •Internal Context

- •Power

- •The Sources of Power

- •Structural Views of Power

- •Do Successful Organizations Need Powerful Managers?

- •The Decision to Allocate Formal Power to Individuals

- •Culture

- •Culture Complements Formal Controls

- •Culture Facilitates Cooperation and Reduces Bargaining Costs

- •Culture, Inertia, and Performance

- •A Word of Caution about Culture

- •External Context, Institutions, and Strategies

- •Institutions and Regulation

- •Interfirm Resource Dependence Relationships

- •Industry Logics: Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Glossary

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

Report Cards • 349

interpret the results. In a similar vein, surveys of existing customers are susceptible to survivor bias, whereby those customers who did not like the product or service no longer use it and therefore are not surveyed. This is a problem for Amazon.com and similar ratings sites. Fans of specific authors and musicians tend to purchase their latest books and download their CDs and are also more likely to post rave reviews. A consumer who visits Amazon to learn about an unfamiliar author or musician will not see a representative set of reviews.

Customer demographics can also affect satisfaction ratings. For example, a study of patient satisfaction with mental health providers found that women and older patients tended to be more satisfied, even though the quality of care they received was objectively similar to the quality offered to younger, male patients.14 Satisfaction can also vary with the customer’s race, income, and education. As a result of these biases, firms that get good report card scores may not provide the best quality. Instead, they may simply be serving the “right customers”—those who tend to give higher scores as a matter of course. Not only does this add unwanted noise to report card rankings, it gives firms an incentive to judiciously choose their customers. In order to defeat these problems, the certifier should adjust the scores to account for differences in customer characteristics. Nowhere is the need to adjust quality ratings for customer characteristics more apparent than in health care, where report card scores that are not risk adjusted are worthless.

Risk Adjustment

Consider three surgeons, Doctors A, B, and C, performing the same hip replacement procedure on patients 1, 2, and 3. Patient 1 survives the surgery with no complications and six months later is able to do all normal daily activities such as climbing stairs and walking the dog. Patient 2 suffers a postoperative infection and, as a result, is never again able to climb stairs and walks with a pronounced limp. Patient 3’s surgery is uneventful, but the patient also never fully regains mobility. It might be tempting to conclude that Doctor A did a better job than Doctors B and C, but this would be premature. Many factors besides the surgeon’s skill determine outcomes. The anesthesiologist, nursing team, and physical therapist all play big roles, which is why it is important to consider the quality of the hospital and not just the individual surgeon.

Surgical outcomes also depend on the patient. Patient 1 may have been more persistent during weeks of painful rehabilitation. Patient 2 might have been older or frailer, while patient 3 lacked the financial resources to hire a caregiver after returning home from the hospital. Any of these factors may have contributed to patient 1’s superior outcome, yet none should reflect badly on Doctors B and C.

In order to properly evaluate the quality of a medical provider, it is essential to perform risk adjustment. Risk adjustment is a statistical process in which raw outcome measures, such as a surgeon’s average patient mortality rate, are adjusted for factors that are beyond the control of the seller.15 Health care provider report cards that do not perform some form of risk adjustment can be extremely misleading. Bear in mind that the best medical providers often get the toughest cases. If report cards are not risk adjusted, the best providers can end up at the bottom of the rankings. Example 10.5 explains the risk adjustments used in one of the first and best hospital quality report cards—the New York State cardiac surgery report card.

Certifiers should perform risk adjustment whenever measured quality depends on the characteristics of the customer. This includes all quality reports based on customer satisfaction as well as report cards for services such as health care and education.

350 • Chapter 10 • Information and Value Creation

The certifier can follow the steps in Example 10.5, substituting the outcomes and risk adjusters that are appropriate for the industry in question. Unfortunately, most certifiers outside of health care do not perform any kind of risk adjustment, making it difficult to confidently identify the best quality sellers. For example, education metrics such as test scores and graduation rates may say more about student demographics than they do about teaching quality. Or consider the widely cited on-time arrival and lost baggage statistics for airlines. Southwest Airlines routinely outperforms other major U.S airlines on these dimensions of performance. Although many industry analysts cite this as evidence of Southwest’s operational excellence, it more likely reflects Southwest’s “point-to-point” route system, which is far easier to operate than the other carriers’ “hub-and-spoke” systems. On any given origin/ destination pair, Southwest may perform no better than other carriers. To take another example, one of the most widely cited metrics in consumer goods—the Consumer Reports automobile and appliance repair frequencies—may reflect how customers use different brands as much as the reliability of those brands. BMW drivers may accelerate hard and brake harder, while Lexus drivers may pamper their cars. Resulting differences in repair records may have little to do with actual build quality.

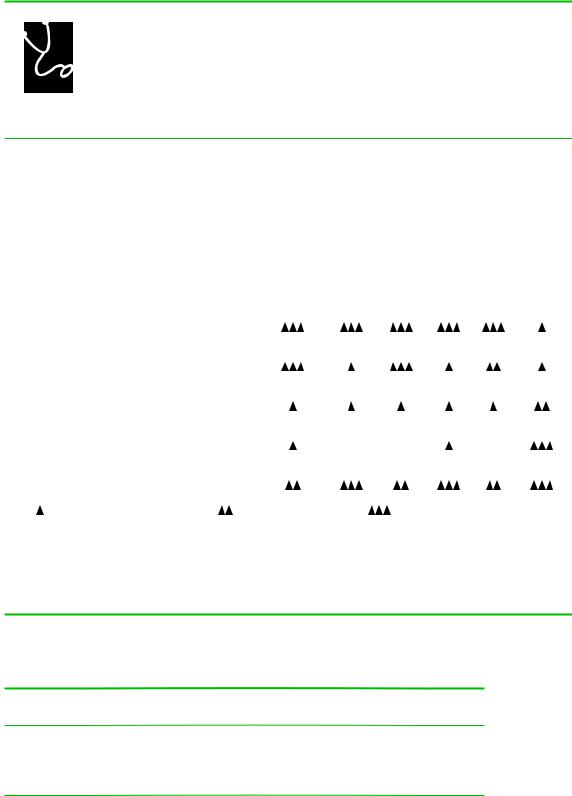

Presenting Report Card Results

The presentation of report card scores can have a big effect on their impact. For many years, General Motors collected enormous quantities of data on the quality of the health plans available to its enrollees. Beginning in 1996, GM provided this information to its employees in the form of easy to understand “diamond” ratings, as shown in Figure 10.1. Plans could receive up to three diamonds in each of six categories, including “Preventive Care” and “Access to Care.” Employees responded by dropping from low scoring plans.16 GM believed that the simplicity of the presentation was crucial to the success of the report card.

Another important feature of the GM report card was that it captured dozens of quality metrics using just six scores. GM did this by creating composite scores—scores that summarize the information in multiple measures. Other report cards that present composite scores include U.S. News and World Reports’ rankings of universities and of hospitals as well as the World Health Organization’s rankings of national health systems.

The simplest way to create a composite score is to sum up or average individual scores. This of course requires all of the individual component scores to be measured on the same numeric scale. For example, when computing a composite ranking of universities, one might use the following scoring procedure:

•Acceptance Rate Score 5 100 2 Acceptance Rate

•Yield Score 5 Yield

•High School GPA Score 5 (Average HS GPA/4) 3 100

Composite score 5 (Acceptance Rate Score 1 Yield Score 1 High School GPA Score)/3 Using this formula, one can compute and compare composite scores for different

universities. Table 10.4 gives an example.

The composite scores in Table 10.4 weight each component score equally. It is often appropriate to emphasize some scores more than others by computing a weighted average score. A student’s grade point average is the weighted average of individual class grades, where the weights are the credit hours for each class. U.S. News’

Report Cards • 351

FIGURE 10.1

COMPARING YOUR 1997 GM MEDICAL OPTIONS

The following table shows the rating of the HMO option(s) available in eight selected quality measures. The ratings are based on historical data and therefore may not necessarily represent the quality of care you will receive in the future. GM does not endorse or recommend any particular medical plan option. The medical plan you elect is your personal decision.

For a more complete description of the eight selected quality measures, see the GM Medical Plan Guide.

|

|

|

|

|

Medical/ |

|

|

|

|

NCQA |

Benchmark |

Operational |

Preventive |

Surgical |

Women’s |

Access |

Patient |

|

Accredited? |

HMO? |

Performance |

Care |

Care |

Health |

to Care |

Satisfaction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basic Medical Plan |

|

|

Information Currently Not Available |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0002 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enhanced Medical Plan |

|

|

Information Currently Not Available |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PPO 2190 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Blue Preferred Plus |

|

|

Information Currently Not Available |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HMO 2103 |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Health Alliance Plan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HMO 2104 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BCN Southeast Michigan |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HMO 2106 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SelectCare HMO |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HMO 2109 |

Yes |

No |

|

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

|

OmniCare Health Plan |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HMO 2119 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Care Choices HMO |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

Key: = below expected performance |

= average performance |

= superior performance |

|

|||||

ND = no data was available from this plan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

HMO and PPO options are based on the plan service area. Eligibility is determined by zip code. You may not be eligible for any or all options listed. You may be eligible for other options if you live near a state line. See your enrollment information for your available options.

Michigan – Detroit

TABLE 10.4

Composite Report Scores for Universities

|

Acceptance |

Acceptance |

Yield |

Yield |

|

GPA |

Composite |

School |

Rate |

Rate Score |

|

Score |

GPA |

Score |

Score |

Eastern U. |

30% |

70 |

30% |

30 |

3.2 |

80 |

60 |

Western U. |

15% |

85 |

50% |

50 |

3.6 |

90 |

75 |

Southern U. |

60% |

40 |

40% |

40 |

2.8 |

70 |

50 |

Northern U. |

80% |

20 |

40% |

40 |

2.4 |

60 |

40 |

352 • Chapter 10 • Information and Value Creation

EXAMPLE 10.5 HOSPITAL REPORT CARDS

In 1999, the U.S. Institutes of Medicine published To Err Is Human, which reported that preventable medical errors caused as many as 100,000 deaths annually. In a subsequent study,

Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institutes of Medicine (IOM) identified several ways that providers can minimize errors, for example, by avoiding administering counterindicated medications.

In the previous year, health services researcher Robert Brook published an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, in which he wrote:

Thousands of studies . . . have shown that the level of quality care provided to the average person leaves a great deal to be desired and . . .

the variation in quality of care by physician or by hospital is immense.17

The IOM told us that medical providers make mistakes and these mistakes can kill. Brook went further, telling us that some providers make more mistakes than others.

In most markets, sellers of substandard quality goods and services (i.e., sellers with low “B”) must accept lower prices, lower quantities, or both. Health care experts have long suspected that this basic market mechanism is absent in medicine. Insurers have historically fixed prices for given services without regard to quality, with some arguing that when quality suffers, patients need more medical care and payments increase! Patients seem unable to compare quality, choosing their providers on the basis of bedside manner rather than on mortality rates. Who could blame them? Quantitative information about provider quality ranges from nonexistent to hard-to-find. In the past two decades, some policy makers, as well as some investor-owned enterprises, have sought to fill this information void.

In 1990, New York State introduced cardiac surgery report cards. The methods used by New York have been often copied, but New York has superior data, thanks to a requirement that hospitals submit detailed patient

diagnostic information that can be used for “risk adjustment.” Here is a summary of how New York constructs its report card; similar methods are used in virtually all other provider report cards.

1.Collect individual-level data, including the outcome (mortality) and clinical indicators that predict mortality.

2.Compute the average mortality rate for each provider’s patients.

3.Use statistical models to predict how patient characteristics affect the probability of mortality.

4.Use the model from step (3) to predict mortality for each patient.

5.Use the predictions from step (4) to compute the average predicted mortality for each provider’s patients. At the same time, compute the standard deviation of these predictions.

6.Compute the difference between the actual outcomes and predicted outcomes for every provider. The difference is each provider’s risk-adjusted quality. Use the standard deviations to determine if differences in riskadjusted quality are statistically meaningful.

Research shows that report cards like these have had several benefits. Demand has shifted toward higher ranked providers, overall quality seems to have increased, and there even seems to be better sorting of the sickest patients to the best providers. But researchers have also identified more nefarious market responses. Some hospitals may be gaming the system by reporting that their patients are very sick (a tactic known as upcoding) in order to improve their risk-adjusted score. Others may be shunning patients whose risk of dying (as perceived by the hospital) may be higher than the predicted risk (based on the model). For example, one study finds that hospitals have reduced surgical rates on Blacks and Hispanics, two groups with above-average mortality risk when compared with the predictions of the riskadjustment models.