- •BUSINESSES IN THE BOOK

- •Preface

- •Brief Contents

- •CONTENTS

- •Why Study Strategy?

- •Why Economics?

- •The Need for Principles

- •So What’s the Problem?

- •Firms or Markets?

- •A Framework for Strategy

- •Boundaries of the Firm

- •Market and Competitive Analysis

- •Positioning and Dynamics

- •Internal Organization

- •The Book

- •Endnotes

- •Costs

- •Cost Functions

- •Total Cost Functions

- •Fixed and Variable Costs

- •Average and Marginal Cost Functions

- •The Importance of the Time Period: Long-Run versus Short-Run Cost Functions

- •Sunk versus Avoidable Costs

- •Economic Costs and Profitability

- •Economic versus Accounting Costs

- •Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

- •Demand and Revenues

- •Demand Curve

- •The Price Elasticity of Demand

- •Brand-Level versus Industry-Level Elasticities

- •Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue Functions

- •Theory of the Firm: Pricing and Output Decisions

- •Perfect Competition

- •Game Theory

- •Games in Matrix Form and the Concept of Nash Equilibrium

- •Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Doing Business in 1840

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Doing Business in 1910

- •Business Conditions in 1910: A “Modern” Infrastructure

- •Production Technology

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Government

- •Doing Business Today

- •Modern Infrastructure

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Infrastructure in Emerging Markets

- •Three Different Worlds: Consistent Principles, Changing Conditions, and Adaptive Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Definitions

- •Definition of Economies of Scale

- •Definition of Economies of Scope

- •Economies of Scale Due to Spreading of Product-Specific Fixed Costs

- •Economies of Scale Due to Trade-offs among Alternative Technologies

- •“The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market”

- •Special Sources of Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Density

- •Purchasing

- •Advertising

- •Costs of Sending Messages per Potential Consumer

- •Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

- •Research and Development

- •Physical Properties of Production

- •Inventories

- •Complementarities and Strategic Fit

- •Sources of Diseconomies of Scale

- •Labor Costs and Firm Size

- •Spreading Specialized Resources Too Thin

- •Bureaucracy

- •Economies of Scale: A Summary

- •The Learning Curve

- •The Concept of the Learning Curve

- •Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

- •Learning and Organization

- •The Learning Curve versus Economies of Scale

- •Diversification

- •Why Do Firms Diversify?

- •Efficiency-Based Reasons for Diversification

- •Scope Economies

- •Internal Capital Markets

- •Problematic Justifications for Diversification

- •Diversifying Shareholders’ Portfolios

- •Identifying Undervalued Firms

- •Reasons Not to Diversify

- •Managerial Reasons for Diversification

- •Benefits to Managers from Acquisitions

- •Problems of Corporate Governance

- •The Market for Corporate Control and Recent Changes in Corporate Governance

- •Performance of Diversified Firms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Make versus Buy

- •Upstream, Downstream

- •Defining Boundaries

- •Some Make-or-Buy Fallacies

- •Avoiding Peak Prices

- •Tying Up Channels: Vertical Foreclosure

- •Reasons to “Buy”

- •Exploiting Scale and Learning Economies

- •Bureaucracy Effects: Avoiding Agency and Influence Costs

- •Agency Costs

- •Influence Costs

- •Organizational Design

- •Reasons to “Make”

- •The Economic Foundations of Contracts

- •Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

- •Bounded Rationality

- •Difficulties Specifying or Measuring Performance

- •Asymmetric Information

- •The Role of Contract Law

- •Coordination of Production Flows through the Vertical Chain

- •Leakage of Private Information

- •Transactions Costs

- •Relationship-Specific Assets

- •Forms of Asset Specificity

- •The Fundamental Transformation

- •Rents and Quasi-Rents

- •The Holdup Problem

- •Holdup and Ex Post Cooperation

- •The Holdup Problem and Transactions Costs

- •Contract Negotiation and Renegotiation

- •Investments to Improve Ex Post Bargaining Positions

- •Distrust

- •Reduced Investment

- •Recap: From Relationship-Specific Assets to Transactions Costs

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •What Does It Mean to Be “Integrated?”

- •The Property Rights Theory of the Firm

- •Alternative Forms of Organizing Transactions

- •Governance

- •Delegation

- •Recapping PRT

- •Path Dependence

- •Making the Integration Decision

- •Technical Efficiency versus Agency Efficiency

- •The Technical Efficiency/Agency Efficiency Trade-off

- •Real-World Evidence

- •Double Marginalization: A Final Integration Consideration

- •Alternatives to Vertical Integration

- •Tapered Integration: Make and Buy

- •Franchising

- •Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

- •Implicit Contracts and Long-Term Relationships

- •Business Groups

- •Keiretsu

- •Chaebol

- •Business Groups in Emerging Markets

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitor Identification and Market Definition

- •The Basics of Competitor Identification

- •Example 5.1 The SSNIP in Action: Defining Hospital Markets

- •Putting Competitor Identification into Practice

- •Empirical Approaches to Competitor Identification

- •Geographic Competitor Identification

- •Measuring Market Structure

- •Market Structure and Competition

- •Perfect Competition

- •Many Sellers

- •Homogeneous Products

- •Excess Capacity

- •Monopoly

- •Monopolistic Competition

- •Demand for Differentiated Goods

- •Entry into Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Oligopoly

- •Cournot Quantity Competition

- •The Revenue Destruction Effect

- •Cournot’s Model in Practice

- •Bertrand Price Competition

- •Why Are Cournot and Bertrand Different?

- •Evidence on Market Structure and Performance

- •Price and Concentration

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •6: Entry and Exit

- •Some Facts about Entry and Exit

- •Entry and Exit Decisions: Basic Concepts

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Bain’s Typology of Entry Conditions

- •Analyzing Entry Conditions: The Asymmetry Requirement

- •Structural Entry Barriers

- •Control of Essential Resources

- •Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Marketing Advantages of Incumbency

- •Barriers to Exit

- •Entry-Deterring Strategies

- •Limit Pricing

- •Is Strategic Limit Pricing Rational?

- •Predatory Pricing

- •The Chain-Store Paradox

- •Rescuing Limit Pricing and Predation: The Importance of Uncertainty and Reputation

- •Wars of Attrition

- •Predation and Capacity Expansion

- •Strategic Bundling

- •“Judo Economics”

- •Evidence on Entry-Deterring Behavior

- •Contestable Markets

- •An Entry Deterrence Checklist

- •Entering a New Market

- •Preemptive Entry and Rent Seeking Behavior

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Microdynamics

- •Strategic Commitment

- •Strategic Substitutes and Strategic Complements

- •The Strategic Effect of Commitments

- •Tough and Soft Commitments

- •A Taxonomy of Commitment Strategies

- •The Informational Benefits of Flexibility

- •Real Options

- •Competitive Discipline

- •Dynamic Pricing Rivalry and Tit-for-Tat Pricing

- •Why Is Tit-for-Tat So Compelling?

- •Coordinating on the Right Price

- •Impediments to Coordination

- •The Misread Problem

- •Lumpiness of Orders

- •Information about the Sales Transaction

- •Volatility of Demand Conditions

- •Facilitating Practices

- •Price Leadership

- •Advance Announcement of Price Changes

- •Most Favored Customer Clauses

- •Uniform Delivered Prices

- •Where Does Market Structure Come From?

- •Sutton’s Endogenous Sunk Costs

- •Innovation and Market Evolution

- •Learning and Industry Dynamics

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •8: Industry Analysis

- •Performing a Five-Forces Analysis

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power and Buyer Power

- •Strategies for Coping with the Five Forces

- •Coopetition and the Value Net

- •Applying the Five Forces: Some Industry Analyses

- •Chicago Hospital Markets Then and Now

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Commercial Airframe Manufacturing

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Professional Sports

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Professional Search Firms

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitive Advantage Defined

- •Maximum Willingness-to-Pay and Consumer Surplus

- •From Maximum Willingness-to-Pay to Consumer Surplus

- •Value-Created

- •Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

- •Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

- •Analyzing Value Creation

- •Value Creation and the Value Chain

- •Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

- •Generic Strategies

- •The Strategic Logic of Cost Leadership

- •The Strategic Logic of Benefit Leadership

- •Extracting Profits from Cost and Benefit Advantage

- •Comparing Cost and Benefit Advantages

- •“Stuck in the Middle”

- •Diagnosing Cost and Benefit Drivers

- •Cost Drivers

- •Cost Drivers Related to Firm Size, Scope, and Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Independent of Firm Size, Scope, or Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Related to Organization of the Transactions

- •Benefit Drivers

- •Methods for Estimating and Characterizing Costs and Perceived Benefits

- •Estimating Costs

- •Estimating Benefits

- •Strategic Positioning: Broad Coverage versus Focus Strategies

- •Segmenting an Industry

- •Broad Coverage Strategies

- •Focus Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The “Shopping Problem”

- •Unraveling

- •Alternatives to Disclosure

- •Nonprofit Firms

- •Report Cards

- •Multitasking: Teaching to the Test

- •What to Measure

- •Risk Adjustment

- •Presenting Report Card Results

- •Gaming Report Cards

- •The Certifier Market

- •Certification Bias

- •Matchmaking

- •When Sellers Search for Buyers

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Market Structure and Threats to Sustainability

- •Threats to Sustainability in Competitive and Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Threats to Sustainability under All Market Structures

- •Evidence: The Persistence of Profitability

- •The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Imperfect Mobility and Cospecialization

- •Isolating Mechanisms

- •Impediments to Imitation

- •Legal Restrictions

- •Superior Access to Inputs or Customers

- •The Winner’s Curse

- •Market Size and Scale Economies

- •Intangible Barriers to Imitation

- •Causal Ambiguity

- •Dependence on Historical Circumstances

- •Social Complexity

- •Early-Mover Advantages

- •Learning Curve

- •Reputation and Buyer Uncertainty

- •Buyer Switching Costs

- •Network Effects

- •Networks and Standards

- •Competing “For the Market” versus “In the Market”

- •Knocking off a Dominant Standard

- •Early-Mover Disadvantages

- •Imperfect Imitability and Industry Equilibrium

- •Creating Advantage and Creative Destruction

- •Disruptive Technologies

- •The Productivity Effect

- •The Sunk Cost Effect

- •The Replacement Effect

- •The Efficiency Effect

- •Disruption versus the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Innovation and the Market for Ideas

- •The Environment

- •Factor Conditions

- •Demand Conditions

- •Related Supplier or Support Industries

- •Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Principal–Agent Relationship

- •Combating Agency Problems

- •Performance-Based Incentives

- •Problems with Performance-Based Incentives

- •Preferences over Risky Outcomes

- •Risk Sharing

- •Risk and Incentives

- •Selecting Performance Measures: Managing Trade-offs between Costs

- •Do Pay-for-Performance Incentives Work?

- •Implicit Incentive Contracts

- •Subjective Performance Evaluation

- •Promotion Tournaments

- •Efficiency Wages and the Threat of Termination

- •Incentives in Teams

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •13: Strategy and Structure

- •An Introduction to Structure

- •Individuals, Teams, and Hierarchies

- •Complex Hierarchy

- •Departmentalization

- •Coordination and Control

- •Approaches to Coordination

- •Types of Organizational Structures

- •Functional Structure (U-form)

- •Multidivisional Structure (M-form)

- •Matrix Structure

- •Matrix or Division? A Model of Optimal Structure

- •Network Structure

- •Why Are There So Few Structural Types?

- •Structure—Environment Coherence

- •Technology and Task Interdependence

- •Efficient Information Processing

- •Structure Follows Strategy

- •Strategy, Structure, and the Multinational Firm

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Social Context of Firm Behavior

- •Internal Context

- •Power

- •The Sources of Power

- •Structural Views of Power

- •Do Successful Organizations Need Powerful Managers?

- •The Decision to Allocate Formal Power to Individuals

- •Culture

- •Culture Complements Formal Controls

- •Culture Facilitates Cooperation and Reduces Bargaining Costs

- •Culture, Inertia, and Performance

- •A Word of Caution about Culture

- •External Context, Institutions, and Strategies

- •Institutions and Regulation

- •Interfirm Resource Dependence Relationships

- •Industry Logics: Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Glossary

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

The Learning Curve • 77

TABLE 2.2

Sources of Scale Economies and Diseconomies

Sources of Economies |

Comment |

Product-specific fixed costs |

These costs include specialized tools and dies, training, and |

|

setup costs; they are usually associated with capital-intensive |

|

production. |

Trade-offs among alternative |

Larger plants may have lower average costs, provided they |

production technologies |

operate near capacity. |

Cube-square rule |

This rule applies whenever output is proportional to the volume |

|

of the production vessel but costs are proportional to the |

|

surface area of the vessel. |

Purchasing |

Larger purchasers can get better prices by reducing seller costs |

|

or by demonstrating greater willingness to shop around. |

Advertising |

Fixed costs of producing advertisements generate scale |

|

economies; umbrella branding spreads marketing costs over |

|

more customers. |

Inventories |

Consolidating inventories reduces stocking and outage costs. |

Ambiguous |

|

Research and development |

Large firms can spread R&D costs. Smaller firms may have |

|

more incentive to innovate and pursue a wider range of |

Sources of Diseconomies |

research ideas. |

|

|

Labor costs |

Larger firms usually pay higher wages, all else equal. |

Spreading resources too thin |

Firms often rely on a few key personnel whose skills cannot be |

|

“replicated.” |

Bureaucracy |

Incentives, information flows, and cooperation can suffer in |

|

large organizations. |

|

|

THE LEARNING CURVE

Medical students are encouraged to learn by the axiom “See one, do one, teach one.” This axiom grossly understates the importance of experience in producing skilled physicians—one surgery is not enough! Experience is an important determinant of ability in many professions, and it is just as important for firms. The importance of experience is conveyed by the idea of the learning curve.

The Concept of the Learning Curve

Economies of scale refer to the advantages that flow from producing a larger output at a given point in time. The learning curve (or experience curve) refers to advantages that flow from accumulating experience and know-how. It is easy to find examples of learning. A manufacturer can learn the appropriate tolerances for producing a system component. A retailer can learn about its customers’ tastes. An accounting firm can learn the idiosyncrasies of its clients’ inventory management. The benefits of learning manifest themselves in lower costs, higher quality, and more effective pricing and marketing.

78 • Chapter 2 • The Horizontal Boundaries of the Firm

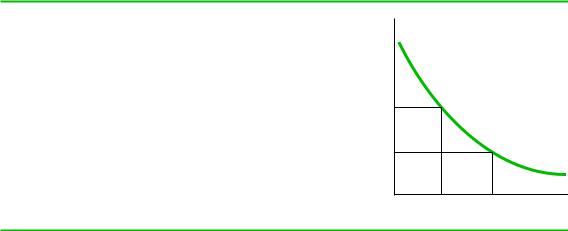

FIGURE 2.7

The Learning Curve

When there is learning, average costs fall with cumulative production. Here, as cumulative production increases from Qx to 2Qx, the average cost of a batch of output falls from AC1 to AC2.

$ Per unit

AC1

AC2

AC

Qx 2Qx

Cumulative production

The magnitude of learning benefits is often expressed in terms of a slope. The slope for a given production process is calculated by examining how far average costs decline as cumulative production output doubles. It is important to use cumulative output rather than output during a given time period to distinguish between learning effects and simple economies of scale. As shown in Figure 2.7, suppose that a firm has cumulative output of Qx with average cost of production of AC1. Suppose next that the firm’s cumulative output doubles to 2Qx with average cost of AC2. Then the slope equals AC2/AC1.

Slopes have been estimated for hundreds of products.10 The median slope appears to be about .80, implying that for the typical firm, doubling cumulative output reduces unit costs by about 20 percent. Slopes vary from firm to firm and industry to industry, however, so that the actual slope enjoyed by any one firm for any given production process generally falls between .70 and .90 and may be as low as .6 or as high as 1.0 (e.g., no learning). Note that estimated slopes usually represent averages over a range of outputs and do not indicate whether or when learning economies are fully exploited.

While most studies of the learning curve focus on costs, some studies have documented the effects of learning on quality. Example 2.3 discusses a recent study of learning in medicine, where experience can literally be a matter of life and death.

Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

When firms benefit from learning, they may want to ramp up production well past the point where the additional revenues offset the added costs. This strategy makes intuitive sense, because it allows the firm to move down the learning curve and realize lower costs in the future. Though it might seem to violate the cardinal rule of equating marginal revenue to marginal cost (see the Economics Primer), the strategy is in fact completely consistent with this rule if one properly construes the cost of current production in the presence of learning. To see why this is so, consider the following example:

Suppose that a manufacturer of DRAM chips has cumulative production of 10,000 chips. The cost to manufacture one additional chip is $2.50. The firm believes

The Learning Curve • 79

EXAMPLE 2.3 LEARNING BY DOING IN MEDICINE

Learning curves are usually estimated for costs—as firms accumulate experience, the cost of production usually falls. But learning manifests itself in other ways, perhaps none as vital as in medicine, where learning can literally be a matter of life and death.

Researchers have long noted that highvolume providers seem to obtain better outcomes for their patients. This volume/outcome relationship appears dramatically in the so-called January/July effect. This is the well-documented fact that mortality rates at teaching hospitals spike in early January and July. One might explain the January spike as the after-effect of New Year’s Eve revelry, but that won’t explain July. The real reason is that medical residents usually change their specialty rotations in January and July. Hospital patients during these time periods are therefore being treated by doctors who may have no experience treating their particular ailments. Many other studies document the problems of newly minted physicians.

But the volume/outcome relationship also applies to established physicians. Back in the 1970s, this was taken as prima facie evidence of a learning curve. But there is another plausible explanation for the relationship—perhaps highquality physicians receive more referrals. If so, then outcomes drive volume, not vice versa. This might not matter to patients who would clearly be served by visiting a high-volume provider regardless of how this chicken/egg question was resolved, but it would matter to policy

makers who have often proposed limiting the number of specialists in certain fields on the grounds that entry dilutes learning.

There is a statistical methodology that can be used to sort out causality. The technique is commonly known as instrumental variables regression and requires identifying some phenomenon that affects only one side of the causality puzzle. In this case, the phenomenon would have to affect volume but not outcomes. Statistical analysis could then be used to unambiguously assess if higher volumes really do lead to better outcomes.

In a recent study, Subramaniam Ramanarayanan used instrumental variables regression to study the learning curve.11 He studied cardiac surgery, where mortality rates for physicians can vary from below 2 percent to above 10 percent. As an instrument, Ramanarayanan chose the retirement of a geographically proximate heart surgeon. When a surgeon retires, volumes of other surgeons can increase by 20 patients or more annually. Retirement is a good instrument because it affects volumes but does not otherwise affect outcomes. Ramanarayanan found that surgeons who treat more patients after the retirement of a colleague enjoy better outcomes. Each additional surgical procedure reduces the probability of patient mortality by 0.14 percent. This reduction is enjoyed by all of the surgeon’s patients. Ramanarayanan’s study offers compelling evidence that surgeons need to maintain high volumes to be at their best.

that once it has produced 100,000 chips its unit costs will fall to $2.00, with no further learning benefits. The company has orders to produce an additional 200,000 chips when it unexpectedly receives a request to produce 10,000 chips to be filled immediately. Given the current unit cost of $2.50 per chip, it might seem that the firm would be unwilling to accept anything less than $25,000 for this order. This might be a mistake, as the true marginal cost is less than the current unit cost.

To determine the true marginal cost, the chip maker must consider how its accumulated experience will affect future costs. Before it received the new order, the chip maker had planned to produce 200,000 chips. The first 100,000 would cost $2.50 per chip, and the remaining 100,000 would cost $2.00 per chip, for a total of

80 • Chapter 2 • The Horizontal Boundaries of the Firm

$450,000 for 200,000 chips. If the firm takes the new order, then the cost of producing the next 200,000 chips is only $445,000 (90,000 chips @ $2.50 1 110,000 chips @ $2.00).

By filling the new order, the DRAM manufacturer reduces its future production costs by $5,000. In effect, the incremental cost of filling the additional order is only $20,000, which is the current costs of $25,000 less the $5,000 future cost savings. Thus, the true marginal cost per chip is $2.00. The firm should be willing to accept any price over this amount, even though a price between $2.00 and $2.50 per chip does not cover current production costs.

In general, when a firm enjoys the benefits of a learning curve, the marginal cost of increasing current production is the expected marginal cost of the last unit of production the firm expects to sell. (This formula is complicated somewhat by discounting future costs.) This implies that learning firms should be willing to price below short-run costs. They may earn negative accounting profits in the short run but will prosper in the long run.

Managers who are rewarded on the basis of short-run profits may be reluctant to exploit the benefits of the learning curve. Firms could solve this problem by directly accounting for learning curve benefits when assessing profits and losses. Few firms that aggressively move down the learning curve have accounting systems that properly measure marginal costs, however, and instead rely on direct growth incentives while placing less emphasis on profits.

Learning and Organization

Firms can take steps to improve learning and the retention of knowledge in the organization. Firms can facilitate the adoption and use of newly learned ideas by encouraging the sharing of information, establishing work rules that include the new ideas, and reducing turnover. Lanier Benkard argues that labor policies at Lockheed prevented the airframe manufacturer from fully exploiting learning opportunities in the production of the L-1011 TriStar.12 Its union contract required Lockheed to promote experienced line workers to management, while simultaneously upgrading workers at lower levels. This produced a domino effect whereby as many as 10 workers changed jobs when one was moved to a management position. As a result, workers were forced to relearn tasks that their higher-ranking coworkers had already mastered. Benkard estimates that this and related policies reduced labor productivity at Lockheed by as much as 40 to 50 percent annually.

While codifying work rules and reducing job turnover facilitates retention of knowledge, it may stifle creativity. At the same time, there are instances where workerspecific learning is too complex to transmit across the firm. Examples include many professional services, in which individual knowledge of how to combine skills in functional areas with specific and detailed knowledge of particular clients may give individuals advantages that they cannot easily pass along to others. Clearly, an important skill of managers is to find the correct balance between stability and change so as to maximize the benefits of learning.

Managers should also draw a distinction between firm-specific and task-specific learning. If learning is task-specific rather than firm-specific, then workers who acquire skill through learning may be able to shop around their talents and capture the value for themselves in the form of higher wages. When learning is firm-specific, worker knowledge is tied to their current employment, and the firm will not have to raise wages as the workers become more productive. Managers should encourage