- •BUSINESSES IN THE BOOK

- •Preface

- •Brief Contents

- •CONTENTS

- •Why Study Strategy?

- •Why Economics?

- •The Need for Principles

- •So What’s the Problem?

- •Firms or Markets?

- •A Framework for Strategy

- •Boundaries of the Firm

- •Market and Competitive Analysis

- •Positioning and Dynamics

- •Internal Organization

- •The Book

- •Endnotes

- •Costs

- •Cost Functions

- •Total Cost Functions

- •Fixed and Variable Costs

- •Average and Marginal Cost Functions

- •The Importance of the Time Period: Long-Run versus Short-Run Cost Functions

- •Sunk versus Avoidable Costs

- •Economic Costs and Profitability

- •Economic versus Accounting Costs

- •Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

- •Demand and Revenues

- •Demand Curve

- •The Price Elasticity of Demand

- •Brand-Level versus Industry-Level Elasticities

- •Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue Functions

- •Theory of the Firm: Pricing and Output Decisions

- •Perfect Competition

- •Game Theory

- •Games in Matrix Form and the Concept of Nash Equilibrium

- •Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Doing Business in 1840

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Doing Business in 1910

- •Business Conditions in 1910: A “Modern” Infrastructure

- •Production Technology

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Government

- •Doing Business Today

- •Modern Infrastructure

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Infrastructure in Emerging Markets

- •Three Different Worlds: Consistent Principles, Changing Conditions, and Adaptive Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Definitions

- •Definition of Economies of Scale

- •Definition of Economies of Scope

- •Economies of Scale Due to Spreading of Product-Specific Fixed Costs

- •Economies of Scale Due to Trade-offs among Alternative Technologies

- •“The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market”

- •Special Sources of Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Density

- •Purchasing

- •Advertising

- •Costs of Sending Messages per Potential Consumer

- •Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

- •Research and Development

- •Physical Properties of Production

- •Inventories

- •Complementarities and Strategic Fit

- •Sources of Diseconomies of Scale

- •Labor Costs and Firm Size

- •Spreading Specialized Resources Too Thin

- •Bureaucracy

- •Economies of Scale: A Summary

- •The Learning Curve

- •The Concept of the Learning Curve

- •Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

- •Learning and Organization

- •The Learning Curve versus Economies of Scale

- •Diversification

- •Why Do Firms Diversify?

- •Efficiency-Based Reasons for Diversification

- •Scope Economies

- •Internal Capital Markets

- •Problematic Justifications for Diversification

- •Diversifying Shareholders’ Portfolios

- •Identifying Undervalued Firms

- •Reasons Not to Diversify

- •Managerial Reasons for Diversification

- •Benefits to Managers from Acquisitions

- •Problems of Corporate Governance

- •The Market for Corporate Control and Recent Changes in Corporate Governance

- •Performance of Diversified Firms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Make versus Buy

- •Upstream, Downstream

- •Defining Boundaries

- •Some Make-or-Buy Fallacies

- •Avoiding Peak Prices

- •Tying Up Channels: Vertical Foreclosure

- •Reasons to “Buy”

- •Exploiting Scale and Learning Economies

- •Bureaucracy Effects: Avoiding Agency and Influence Costs

- •Agency Costs

- •Influence Costs

- •Organizational Design

- •Reasons to “Make”

- •The Economic Foundations of Contracts

- •Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

- •Bounded Rationality

- •Difficulties Specifying or Measuring Performance

- •Asymmetric Information

- •The Role of Contract Law

- •Coordination of Production Flows through the Vertical Chain

- •Leakage of Private Information

- •Transactions Costs

- •Relationship-Specific Assets

- •Forms of Asset Specificity

- •The Fundamental Transformation

- •Rents and Quasi-Rents

- •The Holdup Problem

- •Holdup and Ex Post Cooperation

- •The Holdup Problem and Transactions Costs

- •Contract Negotiation and Renegotiation

- •Investments to Improve Ex Post Bargaining Positions

- •Distrust

- •Reduced Investment

- •Recap: From Relationship-Specific Assets to Transactions Costs

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •What Does It Mean to Be “Integrated?”

- •The Property Rights Theory of the Firm

- •Alternative Forms of Organizing Transactions

- •Governance

- •Delegation

- •Recapping PRT

- •Path Dependence

- •Making the Integration Decision

- •Technical Efficiency versus Agency Efficiency

- •The Technical Efficiency/Agency Efficiency Trade-off

- •Real-World Evidence

- •Double Marginalization: A Final Integration Consideration

- •Alternatives to Vertical Integration

- •Tapered Integration: Make and Buy

- •Franchising

- •Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

- •Implicit Contracts and Long-Term Relationships

- •Business Groups

- •Keiretsu

- •Chaebol

- •Business Groups in Emerging Markets

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitor Identification and Market Definition

- •The Basics of Competitor Identification

- •Example 5.1 The SSNIP in Action: Defining Hospital Markets

- •Putting Competitor Identification into Practice

- •Empirical Approaches to Competitor Identification

- •Geographic Competitor Identification

- •Measuring Market Structure

- •Market Structure and Competition

- •Perfect Competition

- •Many Sellers

- •Homogeneous Products

- •Excess Capacity

- •Monopoly

- •Monopolistic Competition

- •Demand for Differentiated Goods

- •Entry into Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Oligopoly

- •Cournot Quantity Competition

- •The Revenue Destruction Effect

- •Cournot’s Model in Practice

- •Bertrand Price Competition

- •Why Are Cournot and Bertrand Different?

- •Evidence on Market Structure and Performance

- •Price and Concentration

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •6: Entry and Exit

- •Some Facts about Entry and Exit

- •Entry and Exit Decisions: Basic Concepts

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Bain’s Typology of Entry Conditions

- •Analyzing Entry Conditions: The Asymmetry Requirement

- •Structural Entry Barriers

- •Control of Essential Resources

- •Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Marketing Advantages of Incumbency

- •Barriers to Exit

- •Entry-Deterring Strategies

- •Limit Pricing

- •Is Strategic Limit Pricing Rational?

- •Predatory Pricing

- •The Chain-Store Paradox

- •Rescuing Limit Pricing and Predation: The Importance of Uncertainty and Reputation

- •Wars of Attrition

- •Predation and Capacity Expansion

- •Strategic Bundling

- •“Judo Economics”

- •Evidence on Entry-Deterring Behavior

- •Contestable Markets

- •An Entry Deterrence Checklist

- •Entering a New Market

- •Preemptive Entry and Rent Seeking Behavior

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Microdynamics

- •Strategic Commitment

- •Strategic Substitutes and Strategic Complements

- •The Strategic Effect of Commitments

- •Tough and Soft Commitments

- •A Taxonomy of Commitment Strategies

- •The Informational Benefits of Flexibility

- •Real Options

- •Competitive Discipline

- •Dynamic Pricing Rivalry and Tit-for-Tat Pricing

- •Why Is Tit-for-Tat So Compelling?

- •Coordinating on the Right Price

- •Impediments to Coordination

- •The Misread Problem

- •Lumpiness of Orders

- •Information about the Sales Transaction

- •Volatility of Demand Conditions

- •Facilitating Practices

- •Price Leadership

- •Advance Announcement of Price Changes

- •Most Favored Customer Clauses

- •Uniform Delivered Prices

- •Where Does Market Structure Come From?

- •Sutton’s Endogenous Sunk Costs

- •Innovation and Market Evolution

- •Learning and Industry Dynamics

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •8: Industry Analysis

- •Performing a Five-Forces Analysis

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power and Buyer Power

- •Strategies for Coping with the Five Forces

- •Coopetition and the Value Net

- •Applying the Five Forces: Some Industry Analyses

- •Chicago Hospital Markets Then and Now

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Commercial Airframe Manufacturing

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Professional Sports

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Professional Search Firms

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitive Advantage Defined

- •Maximum Willingness-to-Pay and Consumer Surplus

- •From Maximum Willingness-to-Pay to Consumer Surplus

- •Value-Created

- •Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

- •Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

- •Analyzing Value Creation

- •Value Creation and the Value Chain

- •Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

- •Generic Strategies

- •The Strategic Logic of Cost Leadership

- •The Strategic Logic of Benefit Leadership

- •Extracting Profits from Cost and Benefit Advantage

- •Comparing Cost and Benefit Advantages

- •“Stuck in the Middle”

- •Diagnosing Cost and Benefit Drivers

- •Cost Drivers

- •Cost Drivers Related to Firm Size, Scope, and Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Independent of Firm Size, Scope, or Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Related to Organization of the Transactions

- •Benefit Drivers

- •Methods for Estimating and Characterizing Costs and Perceived Benefits

- •Estimating Costs

- •Estimating Benefits

- •Strategic Positioning: Broad Coverage versus Focus Strategies

- •Segmenting an Industry

- •Broad Coverage Strategies

- •Focus Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The “Shopping Problem”

- •Unraveling

- •Alternatives to Disclosure

- •Nonprofit Firms

- •Report Cards

- •Multitasking: Teaching to the Test

- •What to Measure

- •Risk Adjustment

- •Presenting Report Card Results

- •Gaming Report Cards

- •The Certifier Market

- •Certification Bias

- •Matchmaking

- •When Sellers Search for Buyers

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Market Structure and Threats to Sustainability

- •Threats to Sustainability in Competitive and Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Threats to Sustainability under All Market Structures

- •Evidence: The Persistence of Profitability

- •The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Imperfect Mobility and Cospecialization

- •Isolating Mechanisms

- •Impediments to Imitation

- •Legal Restrictions

- •Superior Access to Inputs or Customers

- •The Winner’s Curse

- •Market Size and Scale Economies

- •Intangible Barriers to Imitation

- •Causal Ambiguity

- •Dependence on Historical Circumstances

- •Social Complexity

- •Early-Mover Advantages

- •Learning Curve

- •Reputation and Buyer Uncertainty

- •Buyer Switching Costs

- •Network Effects

- •Networks and Standards

- •Competing “For the Market” versus “In the Market”

- •Knocking off a Dominant Standard

- •Early-Mover Disadvantages

- •Imperfect Imitability and Industry Equilibrium

- •Creating Advantage and Creative Destruction

- •Disruptive Technologies

- •The Productivity Effect

- •The Sunk Cost Effect

- •The Replacement Effect

- •The Efficiency Effect

- •Disruption versus the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Innovation and the Market for Ideas

- •The Environment

- •Factor Conditions

- •Demand Conditions

- •Related Supplier or Support Industries

- •Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Principal–Agent Relationship

- •Combating Agency Problems

- •Performance-Based Incentives

- •Problems with Performance-Based Incentives

- •Preferences over Risky Outcomes

- •Risk Sharing

- •Risk and Incentives

- •Selecting Performance Measures: Managing Trade-offs between Costs

- •Do Pay-for-Performance Incentives Work?

- •Implicit Incentive Contracts

- •Subjective Performance Evaluation

- •Promotion Tournaments

- •Efficiency Wages and the Threat of Termination

- •Incentives in Teams

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •13: Strategy and Structure

- •An Introduction to Structure

- •Individuals, Teams, and Hierarchies

- •Complex Hierarchy

- •Departmentalization

- •Coordination and Control

- •Approaches to Coordination

- •Types of Organizational Structures

- •Functional Structure (U-form)

- •Multidivisional Structure (M-form)

- •Matrix Structure

- •Matrix or Division? A Model of Optimal Structure

- •Network Structure

- •Why Are There So Few Structural Types?

- •Structure—Environment Coherence

- •Technology and Task Interdependence

- •Efficient Information Processing

- •Structure Follows Strategy

- •Strategy, Structure, and the Multinational Firm

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Social Context of Firm Behavior

- •Internal Context

- •Power

- •The Sources of Power

- •Structural Views of Power

- •Do Successful Organizations Need Powerful Managers?

- •The Decision to Allocate Formal Power to Individuals

- •Culture

- •Culture Complements Formal Controls

- •Culture Facilitates Cooperation and Reduces Bargaining Costs

- •Culture, Inertia, and Performance

- •A Word of Caution about Culture

- •External Context, Institutions, and Strategies

- •Institutions and Regulation

- •Interfirm Resource Dependence Relationships

- •Industry Logics: Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Glossary

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

304 • Chapter 9 • Strategic Positioning for Competitive Advantage

is the question of whether changes in market demand or the conditions of technology are likely to threaten how the firm creates value. Although this point seems transparent, firms can easily overlook it when they are in the throes of month-to-month battles for market share with their immediate rivals. Evaluating future prospects is also difficult due to the sheer complexity of predicting the future and the risks involved in acting on such predictions.

The history of an industry may also dull managers to the prospects for change. Threats to a firm’s ability to create value often come from outside its immediate group of rivals and may threaten not just the firm, but the whole industry. Honda’s foray into motorcycles in the early 1960s occurred within segments that the dominant producers at the time—Harley-Davidson and British Triumph—had concluded were unprofitable. The revolution in mass merchandising created by Wal-Mart occurred in out-of-the-way locations that companies such as Kmart and Sears had rejected as viable locations for large discount stores. The music recording industry warily eyed Apple’s iPod but was not fully upended until a start-up company called Napster offered users a way to easily (and, at the time, illegally) share music files over the Internet.

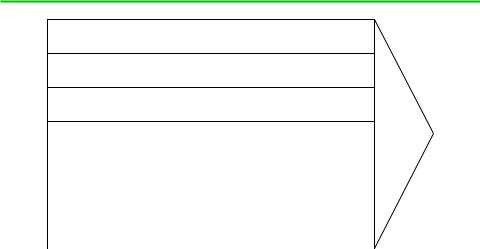

Value Creation and the Value Chain

Value is created as goods move along the vertical chain, which we first described in Chapter 3. The vertical chain is therefore sometimes referred to as the value chain.8 The value chain depicts the firm as a collection of value-creating activities, such as production operations, marketing and sales, and logistics, as Figure 9.7 shows. Each activity in the value chain can potentially add to the benefit B that consumers get from

FIGURE 9.7

Value Chain

Firm infrastructure (e.g., finance, accounting, legal)

Human resource management

Technology development

Procurement

|

Inbound |

Production |

Outbound |

Marketing |

Service |

|

|

logistics |

operations |

logistics |

and sales |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The value chain depicts the firm as a collection of value-creating activities. Porter distinguishes between five primary activities (inbound logistics, production operations, outbound logistics, marketing, and sales and service) and four support activities (firm infrastructure activities, such as finance and accounting, human resources management, technology development, and procurement).

Competitive Advantage and Value Creation: Conceptual Foundations • 305

the firm’s product, and each can add to the cost C that the firm incurs to produce and sell the product. Of course, the forces that influence the benefits created and cost incurred vary significantly across activities.

In practice, it is often difficult to isolate the impact that an activity has on the value that the firm creates. To do so usually requires estimating the incremental perceived benefit that an activity creates and the incremental cost associated with it. However, when different stages produce finished or semifinished goods that can be valued using market prices, we can estimate the incremental value that distinctive parts of the value chain create by using value-added analysis, which we described earlier in this chapter.

Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

Broadly speaking, there are two ways in which a firm can create more economic value than the other firms in its industry. First, it can configure its value chain differently from competitors. For example, in the car-rental market in the United States, Enterprise’s focus on the replacement-car segment has led it to operate with a fundamentally different value chain from the “Airport 7” (Hertz, Avis, National, Alamo, Budget, Dollar, and Thrifty), which are focused on the part of the market whose business originates at airports (primarily business and vacation travelers).9 By optimizing its activities to serve renters seeking to replace their vehicles for possibly prolonged periods of time, Enterprise creates more economic value for this segment of customers than do the Airport 7 (see Example 9.3).

Alternatively, a firm can create superior economic value by configuring its value chain in essentially the same way as its rivals, but within that value chain, performing activities more effectively than rivals do. To do this, the firm must possess resources and capabilities that its competitors lack; otherwise, the competitors could immediately copy any strategy for creating superior value.

Resources are firm-specific assets, such as patents and trademarks, brand-name reputation, installed base, organizational culture, and workers with firm-specific expertise. The brand recognition that Coca-Cola enjoys worldwide is an example of an economically powerful resource. As a testament to the power of Coke’s brand, the marketing consultancy InterBrand estimated that about half of Coca-Cola’s market capitalization in 2010 was due to the value of the Coke brand name alone.11 Unlike nonspecialized assets or factors of production, such as buildings, raw materials, or unskilled labor, resources cannot easily be duplicated or acquired by other firms in well-functioning markets. Resources can directly affect the ability of a firm to create more value than other firms. For example, a large installed base or an established reputation for quality may make the firm’s B higher than its rivals. Resources also indirectly impact value creation because they are the basis of the firm’s capabilities.

Capabilities are activities that a firm does especially well compared with other firms.12 Capabilities might reside within particular business functions (e.g., Virgin Group’s skills in brand promotion, American Airlines’ capabilities in yield management, or Nine West’s ability to manage its sourcing and procurement functions in the fashion shoe business). Alternatively, they may be linked to particular technologies or product designs (e.g., Facebook’s web design and programming skills, Nan Ya Plastics’ skills in working with polyester, or Honda’s legendary skill in working with small internal-combustion engines and power trains).13 Or they might reside in the firm’s ability to manage linkages between elements of the value chain or coordinate activities across it (e.g., the Geisinger Clinic in central Pennsylvania is famous for its use of

306 • Chapter 9 • Strategic Positioning for Competitive Advantage

EXAMPLE 9.3 CREATING VALUE AT ENTERPRISE RENT-A-CAR10

Can you name the largest rental car corporation in the United States? Hertz? Avis? You might be surprised to learn that it is Enterprise Rent-a-Car, a privately held company founded in 1957 by a St. Louis-based Cadillac dealer, Jack Taylor, who named the company for the USS Enterprise, the ship on which he served as a Navy pilot. Enterprise boasts the largest fleet size and number of locations in the United States. Enterprise is also widely believed to be the most profitable rental car firm in the United States. How has Enterprise maintained such profitability and growth in an industry widely believed to be very unattractive? The answer: Enterprise has carved out a unique position in the rental car industry by serving a market segment that historically was ignored by the airportbased rental car companies and by optimizing its value-chain activities to serve this segment.

The “Airport 7” car rental companies— Hertz, Avis, National, Budget, Alamo, Thrifty, and Dollar—cater primarily to the business traveler. While the Airport 7 firms operate out of large, fully stocked parking lots at airports, Enterprise maintains smaller-sized lots in towns and cities across America, which are more accessible to the general population. Moreover, Enterprise will pick customers up at home. The company saves money by not relying on travel agents. Instead, it cultivates relationships with body shops, insurance agents, and auto dealers who, in turn, direct business toward Enterprise. To this end, Enterprise benefited from a legal ruling in 1969 that required insurance companies

to pay for loss of transportation. Enterprise has extended its reach to weekend users, for whom it provides extremely low weekend rates. While almost nonexistent when Enterprise was founded, the replacement-car market now comprises nearly half of the rental car market, of which Enterprise has, by far, the largest share.

In 1999, Enterprise entered the airport market. However, it did so to cater not to the business traveler but to another relatively underserved segment—the infrequent leisure traveler. It offers inexpensive rates while providing valueadded services that an infrequent leisure traveler could appreciate, such as providing directions, restaurant recommendations, and help with luggage. Enterprise now has rental counters at over 200 airports. In a surprise move, Enterprise purchased National and Alamo car rentals in 2007. Taken together, Enterprise/National/Alamo’s airport market share is about equal to erstwhile segment leader Hertz.

The Airport 7 retaliated by dramatically increasing their off-airport sites. Hertz has been particularly aggressive, with over 200 off-airport locations in the United States. Hertz and Avis have even targeted repair shops, but have a long way to go to match the relationships that Enterprise has built in this sector. With its unique mix of activities, it seems likely that Enterprise will sustain its competitive advantage.

As of this writing, Hertz is attempting to acquire Dollar/Thrifty. If successful, the “Airport 7” plus Enterprise will be reduced to the “Everywhere 4.”

health information technology to reinvent how it delivers medical care across the spectrum from primary care through surgery and recovery.)

Whatever their basis, capabilities have several key common characteristics:

1.They are typically valuable across multiple products or markets.

2.They are embedded in what Richard Nelson and Sidney Winter call organi-

zational routines—well-honed patterns of performing activities inside an organization.15 This implies that capabilities can persist even though individuals leave the organization.

3.They are tacit; that is, they are difficult to reduce to simple algorithms or procedure guides.

Competitive Advantage and Value Creation: Conceptual Foundations • 307

EXAMPLE 9.4 MEASURING CAPABILITIES IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY

Drawing on detailed quantitative and qualitative data from 10 major firms, Rebecca Henderson and Iain Cockburn attempted to measure resources and capabilities associated with new drug research in the pharmaceutical industry.14 Although drug discovery is not the only skill that pharmaceutical firms must possess to compete effectively, it is extremely important. Henderson and Cockburn hypothesize that research productivity (measured as the number of patents obtained per research dollar invested) depends on three classes of factors: the composition of a firm’s research portfolio; firm-specific scientific and medical know-how; and a firm’s distinctive capabilities. The composition of the research portfolio is important because it is easier to achieve patentable discoveries in some areas than in others. For example, in the 20 years prior to Henderson and Cockburn’s study, investments in cardiovascular drug discovery were consistently more productive than investments in cancer research. Firm-specific knowhow is critical because modern drug research requires highly skilled scientists from disciplines such as biology, biochemistry, and physiology. Henderson and Cockburn use measures such as the firm’s existing stock of patents as proxies for idiosyncratic firm know-how.

Henderson and Cockburn also hypothesize that two capabilities are likely to be especially significant in new drug research. The first is skill at encouraging and maintaining an extensive flow of scientific information from the external environment to the firm. In pharmaceuticals, much of the fundamental science that lays the groundwork for new discoveries is created outside the firm. A firm’s ability to take advantage of this information is important for its success in making new drug discoveries. Henderson and Cockburn measure the extent of this capability through variables such as the firm’s reliance on publication records in making promotion decisions, its proximity to major research universities, and

its involvement in joint research projects with major universities.

The second capability they focus on is skill at encouraging and maintaining flow of information across disciplinary boundaries inside the firm. Successful new drug discoveries require this type of integration. For example, the commercial development of HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (drugs that inhibit cholesterol synthesis in the liver) depended on pathbreaking work at Merck on three disciplinary fronts: pharmacology, physiology, and biostatistics. Henderson and Cockburn measure this capability with variables such as the extent to which the research in the firm was coordinated through cross-disciplinary teams and giving one person authority to allocate resources for research. The team-based method would facilitate the flow of information across disciplines; the one-person approach would inhibit it.

Henderson and Cockburn’s study indicates that differences in firms’ capabilities explain much variability in firms’ research productivity. For example, a firm that rewards research publications is about 40 percent more productive than one that does not. A firm that organizes by cross-disciplinary research teams is about 25 percent more productive than one that does not. Does this mean that a firm that switches to a team-based research organization will immediately increase its output of patents per dollar by 40 percent? Probably not. This and other measures Henderson and Cockburn used were proxies for deeper resource-creation or integrative capabilities. For example, a firm that rewards publications may have an advantage at recruiting the brightest scientists. A firm that organizes by teams may have a collegial atmosphere that encourages team-based organizations. A team-based organization inside a firm that lacks collegiality may generate far less research productivity. These observations go back to our earlier point. It is often far easier to identify distinctive capabilities once they exist than for management to create them.