- •BUSINESSES IN THE BOOK

- •Preface

- •Brief Contents

- •CONTENTS

- •Why Study Strategy?

- •Why Economics?

- •The Need for Principles

- •So What’s the Problem?

- •Firms or Markets?

- •A Framework for Strategy

- •Boundaries of the Firm

- •Market and Competitive Analysis

- •Positioning and Dynamics

- •Internal Organization

- •The Book

- •Endnotes

- •Costs

- •Cost Functions

- •Total Cost Functions

- •Fixed and Variable Costs

- •Average and Marginal Cost Functions

- •The Importance of the Time Period: Long-Run versus Short-Run Cost Functions

- •Sunk versus Avoidable Costs

- •Economic Costs and Profitability

- •Economic versus Accounting Costs

- •Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

- •Demand and Revenues

- •Demand Curve

- •The Price Elasticity of Demand

- •Brand-Level versus Industry-Level Elasticities

- •Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue Functions

- •Theory of the Firm: Pricing and Output Decisions

- •Perfect Competition

- •Game Theory

- •Games in Matrix Form and the Concept of Nash Equilibrium

- •Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Doing Business in 1840

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Doing Business in 1910

- •Business Conditions in 1910: A “Modern” Infrastructure

- •Production Technology

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Government

- •Doing Business Today

- •Modern Infrastructure

- •Transportation

- •Communications

- •Finance

- •Production Technology

- •Government

- •Infrastructure in Emerging Markets

- •Three Different Worlds: Consistent Principles, Changing Conditions, and Adaptive Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Definitions

- •Definition of Economies of Scale

- •Definition of Economies of Scope

- •Economies of Scale Due to Spreading of Product-Specific Fixed Costs

- •Economies of Scale Due to Trade-offs among Alternative Technologies

- •“The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market”

- •Special Sources of Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Density

- •Purchasing

- •Advertising

- •Costs of Sending Messages per Potential Consumer

- •Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

- •Research and Development

- •Physical Properties of Production

- •Inventories

- •Complementarities and Strategic Fit

- •Sources of Diseconomies of Scale

- •Labor Costs and Firm Size

- •Spreading Specialized Resources Too Thin

- •Bureaucracy

- •Economies of Scale: A Summary

- •The Learning Curve

- •The Concept of the Learning Curve

- •Expanding Output to Obtain a Cost Advantage

- •Learning and Organization

- •The Learning Curve versus Economies of Scale

- •Diversification

- •Why Do Firms Diversify?

- •Efficiency-Based Reasons for Diversification

- •Scope Economies

- •Internal Capital Markets

- •Problematic Justifications for Diversification

- •Diversifying Shareholders’ Portfolios

- •Identifying Undervalued Firms

- •Reasons Not to Diversify

- •Managerial Reasons for Diversification

- •Benefits to Managers from Acquisitions

- •Problems of Corporate Governance

- •The Market for Corporate Control and Recent Changes in Corporate Governance

- •Performance of Diversified Firms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Make versus Buy

- •Upstream, Downstream

- •Defining Boundaries

- •Some Make-or-Buy Fallacies

- •Avoiding Peak Prices

- •Tying Up Channels: Vertical Foreclosure

- •Reasons to “Buy”

- •Exploiting Scale and Learning Economies

- •Bureaucracy Effects: Avoiding Agency and Influence Costs

- •Agency Costs

- •Influence Costs

- •Organizational Design

- •Reasons to “Make”

- •The Economic Foundations of Contracts

- •Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

- •Bounded Rationality

- •Difficulties Specifying or Measuring Performance

- •Asymmetric Information

- •The Role of Contract Law

- •Coordination of Production Flows through the Vertical Chain

- •Leakage of Private Information

- •Transactions Costs

- •Relationship-Specific Assets

- •Forms of Asset Specificity

- •The Fundamental Transformation

- •Rents and Quasi-Rents

- •The Holdup Problem

- •Holdup and Ex Post Cooperation

- •The Holdup Problem and Transactions Costs

- •Contract Negotiation and Renegotiation

- •Investments to Improve Ex Post Bargaining Positions

- •Distrust

- •Reduced Investment

- •Recap: From Relationship-Specific Assets to Transactions Costs

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •What Does It Mean to Be “Integrated?”

- •The Property Rights Theory of the Firm

- •Alternative Forms of Organizing Transactions

- •Governance

- •Delegation

- •Recapping PRT

- •Path Dependence

- •Making the Integration Decision

- •Technical Efficiency versus Agency Efficiency

- •The Technical Efficiency/Agency Efficiency Trade-off

- •Real-World Evidence

- •Double Marginalization: A Final Integration Consideration

- •Alternatives to Vertical Integration

- •Tapered Integration: Make and Buy

- •Franchising

- •Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

- •Implicit Contracts and Long-Term Relationships

- •Business Groups

- •Keiretsu

- •Chaebol

- •Business Groups in Emerging Markets

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitor Identification and Market Definition

- •The Basics of Competitor Identification

- •Example 5.1 The SSNIP in Action: Defining Hospital Markets

- •Putting Competitor Identification into Practice

- •Empirical Approaches to Competitor Identification

- •Geographic Competitor Identification

- •Measuring Market Structure

- •Market Structure and Competition

- •Perfect Competition

- •Many Sellers

- •Homogeneous Products

- •Excess Capacity

- •Monopoly

- •Monopolistic Competition

- •Demand for Differentiated Goods

- •Entry into Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Oligopoly

- •Cournot Quantity Competition

- •The Revenue Destruction Effect

- •Cournot’s Model in Practice

- •Bertrand Price Competition

- •Why Are Cournot and Bertrand Different?

- •Evidence on Market Structure and Performance

- •Price and Concentration

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •6: Entry and Exit

- •Some Facts about Entry and Exit

- •Entry and Exit Decisions: Basic Concepts

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Bain’s Typology of Entry Conditions

- •Analyzing Entry Conditions: The Asymmetry Requirement

- •Structural Entry Barriers

- •Control of Essential Resources

- •Economies of Scale and Scope

- •Marketing Advantages of Incumbency

- •Barriers to Exit

- •Entry-Deterring Strategies

- •Limit Pricing

- •Is Strategic Limit Pricing Rational?

- •Predatory Pricing

- •The Chain-Store Paradox

- •Rescuing Limit Pricing and Predation: The Importance of Uncertainty and Reputation

- •Wars of Attrition

- •Predation and Capacity Expansion

- •Strategic Bundling

- •“Judo Economics”

- •Evidence on Entry-Deterring Behavior

- •Contestable Markets

- •An Entry Deterrence Checklist

- •Entering a New Market

- •Preemptive Entry and Rent Seeking Behavior

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Microdynamics

- •Strategic Commitment

- •Strategic Substitutes and Strategic Complements

- •The Strategic Effect of Commitments

- •Tough and Soft Commitments

- •A Taxonomy of Commitment Strategies

- •The Informational Benefits of Flexibility

- •Real Options

- •Competitive Discipline

- •Dynamic Pricing Rivalry and Tit-for-Tat Pricing

- •Why Is Tit-for-Tat So Compelling?

- •Coordinating on the Right Price

- •Impediments to Coordination

- •The Misread Problem

- •Lumpiness of Orders

- •Information about the Sales Transaction

- •Volatility of Demand Conditions

- •Facilitating Practices

- •Price Leadership

- •Advance Announcement of Price Changes

- •Most Favored Customer Clauses

- •Uniform Delivered Prices

- •Where Does Market Structure Come From?

- •Sutton’s Endogenous Sunk Costs

- •Innovation and Market Evolution

- •Learning and Industry Dynamics

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •8: Industry Analysis

- •Performing a Five-Forces Analysis

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power and Buyer Power

- •Strategies for Coping with the Five Forces

- •Coopetition and the Value Net

- •Applying the Five Forces: Some Industry Analyses

- •Chicago Hospital Markets Then and Now

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Commercial Airframe Manufacturing

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Barriers to Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Professional Sports

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Professional Search Firms

- •Market Definition

- •Internal Rivalry

- •Entry

- •Substitutes and Complements

- •Supplier Power

- •Buyer Power

- •Conclusion

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Competitive Advantage Defined

- •Maximum Willingness-to-Pay and Consumer Surplus

- •From Maximum Willingness-to-Pay to Consumer Surplus

- •Value-Created

- •Value Creation and “Win–Win” Business Opportunities

- •Value Creation and Competitive Advantage

- •Analyzing Value Creation

- •Value Creation and the Value Chain

- •Value Creation, Resources, and Capabilities

- •Generic Strategies

- •The Strategic Logic of Cost Leadership

- •The Strategic Logic of Benefit Leadership

- •Extracting Profits from Cost and Benefit Advantage

- •Comparing Cost and Benefit Advantages

- •“Stuck in the Middle”

- •Diagnosing Cost and Benefit Drivers

- •Cost Drivers

- •Cost Drivers Related to Firm Size, Scope, and Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Independent of Firm Size, Scope, or Cumulative Experience

- •Cost Drivers Related to Organization of the Transactions

- •Benefit Drivers

- •Methods for Estimating and Characterizing Costs and Perceived Benefits

- •Estimating Costs

- •Estimating Benefits

- •Strategic Positioning: Broad Coverage versus Focus Strategies

- •Segmenting an Industry

- •Broad Coverage Strategies

- •Focus Strategies

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The “Shopping Problem”

- •Unraveling

- •Alternatives to Disclosure

- •Nonprofit Firms

- •Report Cards

- •Multitasking: Teaching to the Test

- •What to Measure

- •Risk Adjustment

- •Presenting Report Card Results

- •Gaming Report Cards

- •The Certifier Market

- •Certification Bias

- •Matchmaking

- •When Sellers Search for Buyers

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Market Structure and Threats to Sustainability

- •Threats to Sustainability in Competitive and Monopolistically Competitive Markets

- •Threats to Sustainability under All Market Structures

- •Evidence: The Persistence of Profitability

- •The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Imperfect Mobility and Cospecialization

- •Isolating Mechanisms

- •Impediments to Imitation

- •Legal Restrictions

- •Superior Access to Inputs or Customers

- •The Winner’s Curse

- •Market Size and Scale Economies

- •Intangible Barriers to Imitation

- •Causal Ambiguity

- •Dependence on Historical Circumstances

- •Social Complexity

- •Early-Mover Advantages

- •Learning Curve

- •Reputation and Buyer Uncertainty

- •Buyer Switching Costs

- •Network Effects

- •Networks and Standards

- •Competing “For the Market” versus “In the Market”

- •Knocking off a Dominant Standard

- •Early-Mover Disadvantages

- •Imperfect Imitability and Industry Equilibrium

- •Creating Advantage and Creative Destruction

- •Disruptive Technologies

- •The Productivity Effect

- •The Sunk Cost Effect

- •The Replacement Effect

- •The Efficiency Effect

- •Disruption versus the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm

- •Innovation and the Market for Ideas

- •The Environment

- •Factor Conditions

- •Demand Conditions

- •Related Supplier or Support Industries

- •Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Principal–Agent Relationship

- •Combating Agency Problems

- •Performance-Based Incentives

- •Problems with Performance-Based Incentives

- •Preferences over Risky Outcomes

- •Risk Sharing

- •Risk and Incentives

- •Selecting Performance Measures: Managing Trade-offs between Costs

- •Do Pay-for-Performance Incentives Work?

- •Implicit Incentive Contracts

- •Subjective Performance Evaluation

- •Promotion Tournaments

- •Efficiency Wages and the Threat of Termination

- •Incentives in Teams

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •13: Strategy and Structure

- •An Introduction to Structure

- •Individuals, Teams, and Hierarchies

- •Complex Hierarchy

- •Departmentalization

- •Coordination and Control

- •Approaches to Coordination

- •Types of Organizational Structures

- •Functional Structure (U-form)

- •Multidivisional Structure (M-form)

- •Matrix Structure

- •Matrix or Division? A Model of Optimal Structure

- •Network Structure

- •Why Are There So Few Structural Types?

- •Structure—Environment Coherence

- •Technology and Task Interdependence

- •Efficient Information Processing

- •Structure Follows Strategy

- •Strategy, Structure, and the Multinational Firm

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •The Social Context of Firm Behavior

- •Internal Context

- •Power

- •The Sources of Power

- •Structural Views of Power

- •Do Successful Organizations Need Powerful Managers?

- •The Decision to Allocate Formal Power to Individuals

- •Culture

- •Culture Complements Formal Controls

- •Culture Facilitates Cooperation and Reduces Bargaining Costs

- •Culture, Inertia, and Performance

- •A Word of Caution about Culture

- •External Context, Institutions, and Strategies

- •Institutions and Regulation

- •Interfirm Resource Dependence Relationships

- •Industry Logics: Beliefs, Values, and Behavioral Norms

- •Chapter Summary

- •Questions

- •Endnotes

- •Glossary

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

402 • Chapter 12 • Performance Measurement and Incentives

THE PRINCIPAL–AGENT RELATIONSHIP

A principal–agent relationship or agency relationship occurs when one party (the agent) is hired by another (the principal) to take actions or make decisions that affect the payoff to the principal.2 As one example, consider the relation between a public firm’s shareholders (the “principal”) and its chief executive officer (CEO) (their agent). The CEO’s job description usually includes strategic planning, hiring operating officers, and managing the organization. If the CEO manages and plans effectively, the firm’s share price will rise and shareholders will be paid larger dividends. If the CEO does a poor job running the firm, the return to shareholders will suffer.

The principal–agent framework is broadly applicable. All of a firm’s employees can be thought of as agents of the firm’s owners, since they all take actions or make decisions that might impact the payoff to the owners. The principal–agent framework can also be used to think about relationships between firms, between professionals and their clients, or even outside of the business world entirely. Advertising agencies act as agents for consumer product companies, doctors act as agents for their patients, and elected officials are expected to act as agents on behalf of voters.

Difficulties in agency relationships can arise when two conditions are met: (1) The objectives of principal and agent are different, and (2) the actions taken by the agent or the information possessed by the agent are hard to observe. We discuss each condition in turn.

The typical principal would like to maximize the difference between the value it receives as a result of the agent’s actions and any payment it makes to the agent. If the agent had the same objective, we would say that the goals of the principal and agent were aligned. But the agent does not directly care about the value generated for the principal; the agent cares about the value it generates for itself. Their interests are normally not aligned. Legal scholar Adolf Berle and economist Gardiner Means were among the first to describe the differences in objectives in the shareholder–CEO agency relationship.3 One important objective of a firm’s shareholders, they wrote, is to “earn the maximum profit compatible with a reasonable degree of risk.” The objectives of management are often harder to discern. Managers may wish to maximize their personal wealth even if shareholders do not benefit. Managers may wish to limit their personal risk, avoiding risky strategic initiatives that shareholders view as “reasonable.” Managers may wish to boost their prospects for another job, and could therefore take actions that pump up the firm’s short-run performance even if shareholders are harmed in the long run. Finally, managers could simply be averse to excessive effort—putting in a series of 80-hour weeks doing strategic planning is, after all, very hard work.

Differences in objectives are not by themselves sufficient to lead to problems in agency relationships. If actions and information are easily observable, then the principal can write a complete contract with the agent that aligns their interests. We discussed complete contracts in Chapter 3, where we identified several reasons why it is difficult to write them. In particular, contracting can be hindered by hidden action or hidden information, things known to the agent but not to the principal. When the principal and agent have different objectives, and the agent can take hidden actions or has hidden information, agency problems can arise.

Combating Agency Problems

One way to mitigate hidden action and hidden information problems is to expend resources watching employees or gathering information that employees use to make

The Principal–Agent Relationship • 403

EXAMPLE 12.1 DIFFERENCES IN OBJECTIVES IN AGENCY RELATIONSHIPS:

YAHOO! AND ENGLISH FRUIT

Differences in objectives in agency relationships can take many forms, and principals must be prepared to think quite broadly about how an agent’s objectives might differ from theirs. Two examples help illustrate this point.

On February 1, 2008, the Internet portal firm Yahoo! received a takeover bid from software giant Microsoft. A corporate takeover occurs when a firm or an individual (Microsoft, in this case) offers to buy all shares in a “target firm” (such as Yahoo!) and thus take control of the target. Negotiations between the two firms led to a revised bid in May of 2008, with Microsoft CEO Steve Balmer reportedly offering $33 per share. Yahoo! CEO Jerry Yang refused, and insisted that the firm was worth at least $37 per share. The firm remained independent as of May 2012.

There are at least three potential explanations for Yang’s decision to turn down Microsoft’s offer. First, it could be the case that Yang believed the firm was worth more than Microsoft’s offer. If, as an independent entity, the firm could generate dividend payments to shareholders with a net present value of more than $33 per share, then accepting Microsoft’s offer would not be in the shareholders’ interest. Note, however, that the firm was trading at a mere $19 per share prior to Microsoft’s February bid, so stock market participants appeared to think that Yahoo’s value as an independent entity was considerably less than Microsoft’s offer.

A second possibility is that Yang was working hard on the shareholders’ behalf to try to maximize the purchase price from Microsoft. If Microsoft’s maximum willingness to pay for Yahoo! was $40, then Yang could merely be trying to drive a hard bargain. If he was eventually able to get Microsoft to increase its offer, then shareholders would benefit.

A third possibility, however, is that Yang had different preferences than shareholders regarding Yahoo!’s independence. Shareholders generally might not care whether Yahoo! is an independent

entity; instead, they just want to maximize the return on their investment. On the other hand, Yang, who founded Yahoo! in 1994 with fellow Stanford engineering grad student Dave Filo, might value the firm’s continued independence for its own sake. Some simple arithmetic will help draw out the implications of this preference. Suppose Yang, who directly and indirectly owned around 50 million Yahoo! shares as of early 2008, believed that Yahoo! could achieve a stock price of $30 as an independent entity. Then, rejecting Microsoft’s $33 offer costs Yang $3 * 50 million 5 $150 million. If Yang (whose holdings in Yahoo were worth around a billion dollars) was willing to give up $150 million in order to keep the firm he founded independent, then his preferences may have differed from those of the firm’s shareholders, and an agency problem may have exist. Some shareholders did seem to be unhappy with Yang; in August of 2008, more than one-third of the firm’s shareholders voted not to reappoint him to the firm’s board.

A second example of differences in objectives in agency relationships comes from a field experiment conducted by economists Oriana Bandiera, Iwan Barankay, and Imran Rasul.4 Bandiera and colleagues visited a fruit farm in England and worked with management to try to improve the efficiency of the firm’s fruit-picking operation. Field workers at the farm were paid “piece rates”—that is, they received a set rate per piece of fruit (or pound of fruit) they picked. Using statistical analysis, the researchers found that worker productivity varied in systematic ways depending on the supervisor to whom the worker was assigned. Worker productivity was highest when the worker and supervisor had a “social connection,” as measured by shared country of origin, shared living quarters, or similar duration of employment at the farm. (Workers at this farm were hired on seasonal contracts and came from eight nations in eastern Europe.)

What can explain this odd pattern? Bandiera and colleagues suggest that supervisors’

404 • Chapter 12 • Performance Measurement and Incentives

social connections led to favoritism. That is, supervisors may simply like some workers more than others and may therefore have a preference for helping some workers more than others, so that the favored workers can earn more money through piece rates. Note that this preference likely differs markedly from that of the fruit farm. The principal (the

fruit farm) does not care which of its fruit pickers earns the highest pay, while the agent (the supervisor) does. Interestingly, favoritism seems to have stopped (and overall fruitpicking efficiency rose) after the firm tied supervisor pay to worker productivity. This suggests that favoritism was not leading supervisors to allocate their efforts in the most efficient manner.

decisions. For example, one important role of corporate boards of directors is to monitor the decisions of the firm’s CEO. Directors are usually themselves current and former top executives at other firms, which can make them skillful monitors of other CEOs. Directors meet regularly and often spend time talking to a firm’s employees, suppliers, and customers. They review financial statements, reports, and investment decisions, and they frequently vote to approve or disapprove major decisions made by the CEO, such as undertaking a large acquisition.

While monitoring can help firms resolve problems of hidden action and information, it does have some significant limitations. First, it is often imperfect. While most members of corporate boards are business experts with years of experience, they typically do not spend more than about 25 days per year on company business. Given the complexity of many large, modern organizations, it is difficult to imagine that directors could digest all information that is relevant for CEO decision making. Second, hiring monitors can be quite costly. Members of corporate boards are paid large retainers (frequently in excess of $250,000 annually). Similarly, general counsels at large corporations earn salaries that can approach a million dollars per year. Even in lower level jobs where managers who monitor employees earn a fraction of the salary paid to a director, such as assembly lines, call centers, and retail sales, these costs can be substantial. Third, hiring a monitor often introduces another layer to the agency relationship. Adding a board of directors may help solve agency conflicts between the shareholders and the CEO, but shareholders may then have to worry about agency conflicts between themselves and the directors.

When principals cannot adequately monitor their agents’ actions, or find it excessively costly to do so, they may prefer to tie pay directly to performance.

PERFORMANCE-BASED INCENTIVES

Using pay-for-performance incentives can mitigate agency conflicts by aligning the interests of the agent and the principal. To do this, the principal links the agent’s pay (or, more generally, the value the agent receives) to the payoff the principal receives from the agent’s action. The agent earns more when the principal does well and less when the principal does badly, and so is more willing to take actions that benefit the principal.

Performance-based incentives are everywhere. Salespeople at department stores like Nordstrom and Galleries Lafayette receive commissions equal to approximately 5 percent of their customers’ purchases. Brand managers at consumer goods firms like Kraft or Maruchan typically receive year-end bonuses that are linked to the profit

Performance-Based Incentives • 405

generated by their brands. Most publicly traded firms grant stock and stock options to chief executive officers, thereby linking CEO wealth to the return that shareholders earn. Firms can also offer nonmonetary rewards—“employee of the month” parking, vacations for top sales agents, and “status” rewards such as plaques and special mention at company events.

The best way to explain the properties of performance-based incentives is with a simple economic model of how a hypothetical employee may respond to such incentives. We will use this model to consider more complex aspects of incentives, so pay careful attention to the notation. Consider a firm that hires an employee to perform a sales function. Let the employee’s effort level be represented by e. Think of units of effort as “hours during which the employee puts forth high effort.” We make this distinction because the principal may be able to observe the number of hours that the employee works, but is unlikely to observe the number of hours during which the employee puts forth high effort. Thus, e represents a hidden action and cannot be included in a contract.

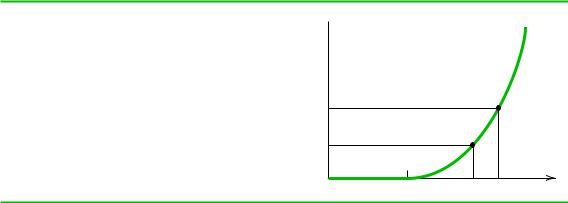

Now suppose that the employee is willing to put forth some high effort regardless of compensation, but will exert extra effort only if compensated in some way. One way to represent this is to write the employee’s cost of exerting effort level e in monetary terms. Specifically, let the cost of exerting effort level e be given by the following formula, which is also depicted in Figure 12.1:

c (e) 5 e |

0 |

if e # 40 |

1@2(e 2 40)2 |

if e . 40 |

The interpretation of this function is as follows. The employee is willing to increase effort from e0 to e1 if and only if the additional compensation (whether monetary or nonmonetary) is at least c(e1) 2 c(e0). The flat region on the curve in Figure 12. 1 indicates that the employee is willing to put in up to 40 units of effort for no extra compensation. However, the employee is willing to exert additional effort beyond 40 units only if compensated for doing so. The cost function is convex, indicating that extra effort becomes more and more costly as the employee’s effort level increases.

Now consider an employee who puts in 40 units of effort and is considering putting in one additional unit of effort. According to the preceding formula, the effort costs the employee c(41) 2 c(40) 5 $0.50. Suppose that each unit of effort generates $100 in extra sales to the principal. Thus, sales 5 $100e. Hence, one additional unit

FIGURE 12.1

A Convex Cost of Effort Function

This employee is willing to exert up to 40 units of effort without being compensated for doing so. The employee is willing to increase effort from e0 to e1 only if compensation will increase by c(e1) 2 c(e0) as a result. The marginal cost of effort increases as the employee works harder.

$ |

c(e) |

|

c(e1)

c(e0)

0 |

40 |

e0 e1 |

Effort |

406 • Chapter 12 • Performance Measurement and Incentives

of effort generates a net surplus of $99.50 for the two parties—the $100 in extra sales captured by the firm less the $0.50 in effort cost borne by the employee. How can the firm get the employee to make the extra effort? If effort were observable, the firm could simply offer to pay the employee an additional $0.50 for the extra unit of effort. As noted earlier, it might not be possible for the firm to observe whether the employee is putting in extra effort, so this offer is not feasible.

Let us consider some compensation schemes that are feasible. Suppose that the firm pays the employee a straight salary that matches the market wage, which we assume is $1,000 per week. The employee’s payoff net of effort costs is $1,000 2 c(e). Given that pay does not depend on sales, the employee in this case is unwilling to put in more than 40 units of effort. Phrased another way, if the employee has nothing to gain from extra effort, then no extra effort should be expected. The employee’s 40 units of effort result in $4,000 in sales, while the wage paid is $1,000. The firm earns $3,000 in profits.

Suppose instead that the firm offers a salary of $1,000 per week, but adds a 10 percent commission on sales. Given that each unit of effort produces an extra $100 of sales, we can write the employee’s payoff as

$1,000 1 0.10(100e) 2 c(e)

The employee will increase effort until the marginal benefit of effort is equal to the marginal cost. As shown in Figure 12.2, the marginal benefit of effort to the employee is always 10 percent of $100, or $10—each unit of effort translates into another $10 in commission. The marginal cost of effort is the slope of the effort curve. The convex shape of this curve implies that it becomes more and more costly for the employee to exert additional effort. A bit of calculus shows that the employee is best off choosing e 5 50; at any effort beyond this, the marginal cost of effort exceeds the marginal

FIGURE 12.2

The Employee Increases Effort Until the Marginal Benefit of

Effort Is Equal to the Marginal Cost

For each unit of effort, the employee expects to gain 10 percent of $100, or $10. Hence, the employee increases effort until the marginal cost of effort (that is, the slope of a line tangent to the cost curve) is equal to $10. This occurs at e 5 50.

$ |

|

|

|

1,000 10% (100e) |

|

40 |

50 |

Effort |

|

|

|

Performance-Based Incentives • 407

benefit.5 When e 5 50, we can calculate the following: total sales are $5,000, the employee’s commission is $500, and total cash compensation is $1,500. The employee’s compensation, net of effort costs, is $1,500 2 0.5(50 2 40)2 5 $1,450, and the firm realizes profits of $5,000 2 $1,500 5 $3,500. Compared with straight salary plan, we see that the increase in wages paid by the firm under the salary-plus-commission plan is more than offset by the increase in the employee’s productivity. Both the firm and its employee are better off.

The firm may be able to achieve even higher profits by slightly adjusting the salary-plus-commission plan. Under the current plan, the employee has net compensation of $1,450, which is $450 more than the market wage. The employee should therefore be willing to accept a contract that offers up to $450 less than the current plan; put another way, the employee should agree to a plan that pays at least $550 plus 10 percent commission. The employee would still put in 50 hours of extra effort and would earn $1,000 in net compensation, just enough to prefer this job to another one at $1,000. The firm would see its profits increase from $3,500 to $3,950.

This example illustrates several key points about performance-based incentives:

1.The slope of the relationship between pay and performance, rather than the absolute pay level, provides incentives for effort. As Figures 12.2 and 12.3 illustrate, raising the employee’s salary (say, from $900 to $1,000) does not change the cost-benefit trade-off determining the employee’s effort choice.

2.The firm earns a higher profit when it offers the salary-plus-commission job than with a fixed salary job.

3.The firm can do even better if it sets a higher commission rate. In fact, the firm’s profit-maximizing commission rate is 100 percent! (That is, the worker keeps all the sales revenues.) Why? The firm would like to maximize total value, which is the difference between total revenues and worker costs. This occurs if the worker

FIGURE 12.3

The Firm Can Offer a Lower Salary without Changing Incentives for Effort

If the firm offers a salary of $900, the employee still selects effort by making a cost-benefit comparison. Since neither the marginal benefit of effort nor the marginal cost is affected, the employee’s effort choice is unchanged.

$ |

|

|

|

|

$900 + 10% (100e) |

40 |

50 |

Effort |

|

|

408 • Chapter 12 • Performance Measurement and Incentives

EXAMPLE 12.2 HIDDEN ACTION AND HIDDEN INFORMATION IN GARMENT

FACTORY FIRE INSURANCE

Immigrants Max Blanck and Isaac Harris were entrepreneurs.7 In the1890s and 1900s, the two men owned and operated several garment factories, each making ladies’ blouses, on New York City’s Lower East Side. The fashion business, then as now, was a risky one. Manufacturers had to make production decisions well in advance of sales, and demand forecasting errors combined with consumers’ fickle tastes often meant that unsold inventory could stack up. This was especially the case in spring and fall, as the winter and summer fashion seasons, respectively, drew to a close.

Around 5 a.m. on April 5, 1902, fire broke out at the Triangle Waist Company, one of Blanck and Harris’s operations. While the early hour meant no one was hurt, the firm’s sewing machines—and notably its inventory of unsold blouses—were destroyed. Fortunately for Blanck and Harris, the firm’s equipment and inventory were insured against fire. The insurers dutifully paid up, and the Triangle Waist Company resumed operations for the upcoming summer season. Around 5 a.m. on November 1, 1902, firefighters again were called to Triangle but were too late to save the stacks of inventory sitting in the firm’s storerooms. Again insurers covered the resulting losses. Another Blanck and Harris operation, the Diamond Waist Company, suffered insured losses in an early morning fire in April 1907. Fire again struck Diamond in April of 1910, again without loss of life but with generous insurance coverage.

While there is no definitive evidence that these fires were intentionally set by Blanck and Harris, it seems hard to imagine that they were not. Each fire occurred as the firm ended a fashion season, when concern over unsold inventory was greatest. The fires all began during off-hours, so that no one was hurt. Further, Blanck and Harris were hardly the only garment factory owners to suffer spring and fall fires with some regularity. A 1913 Collier’s magazine article noted that in seasons when Paris fashion designers turned against feathers,

New York feather factories suddenly began bursting into flames.

Insurance was one of the first industries to have to come to terms with hidden action in agency relationships, as this example of garment factory fire insurance makes clear. A fire insurance contract, where an insurer promises to compensate the insured whole against losses from fire, creates an agency relationship. How? Once the contract is signed, the precautionary actions taken by the insured affect the payoff to the insurer. Suppose the insured is careful to remove any flammable materials from the property, and to keep fire alarms and hoses operational. Or suppose the insured tosses a lit match into a pile of fabric scraps early one April morning. Either action will affect the likelihood of fire, and thus change the likelihood that the insurer will have to make a payout. Thus, the choices made by the agent (the insured) affect the payoff to the principal (the insurer). Insurers use a variety of methods (including linking premiums to the presence of fire detectors, a form of performance-based incentives) to align the interests of insured with insurer.

The insurer/insured agency relationship can also be affected by hidden information. Income annuities are a form of insurance against outliving one’s savings. A retiree makes an upfront payment to an insurer, who then agrees to make fixed monthly payments to the retiree for the remainder of the retiree’s life. The key determinant of insurer profitability when offering this contract is how long the retiree lives. The retiree’s precise life expectancy is, of course, not known to anyone when the contract is signed, but insurers have found that those who purchase income annuities live much longer than average. This suggests that the retirees who purchase annuities have information—presumably about their health status and risk factors—that is not observed by insurers, but that is a factor in determining the payoff to insurers. Insurers are careful to factor this effect into their pricing for income annuities.