- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Introduction

- •2. Evaluation of the Craniomaxillofacial Deformity Patient

- •3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification

- •4. Etiology of Skeletal Malocclusion

- •5. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Traumatic Defects

- •6. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Review of Nasal Deformities

- •7. Review of Benign Tumors of the Maxillofacial Region and Considerations for Bone Invasion

- •8. Oral Malignancies: Etiology, Distribution, and Basic Treatment Considerations

- •9. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Infections: Etiologies, Distributions, and Associated Defects

- •11. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Healing, Biomechanics, and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •12. Metal for Craniomaxillofacial Internal Fixation Implants and Its Physiological Implications

- •13. Bioresorbable Materials for Bone Fixation: Review of Biological Concepts and Mechanical Aspects

- •14. Advanced Bone Healing Concepts in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Bone Surgery

- •15. The ITI Dental Implant System

- •16. Localized Ridge Augmentation Using Guided Bone Regeneration in Deficient Implant Sites

- •17. The ITI Dental Implant System in Maxillofacial Applications

- •18. Maxillary Sinus Grafting and Osseointegration Surgery

- •19. Computerized Tomography and Its Use for Craniomaxillofacial Dental Implantology

- •20B. Atlas of Cases

- •21A. Prosthodontic Considerations in Dental Implant Restoration

- •21B. Overdenture Case Reports

- •22. AO/ASIF Mandibular Hardware

- •23. Aesthetic Considerations in Reconstructive and Corrective Craniomaxillofacial Bone Surgery

- •24. Considerations for Reconstruction of the Head and Neck Oncologic Patient

- •25. Autogenous Bone Grafts in Maxillofacial Reconstruction

- •26. Current Practice and Future Trends in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Microvascular Bone Surgery

- •27. Considerations in the Fixation of Bone Grafts for the Reconstruction of Mandibular Continuity Defects

- •28. Indications and Technical Considerations of Different Fibula Grafts

- •29. Soft Tissue Flaps for Coverage of Craniomaxillofacial Osseous Continuity Defects with or Without Bone Graft and Rigid Fixation

- •30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting

- •31. Microsurgical Reconstruction of Large Defects of the Maxilla, Midface, and Cranial Base

- •32. Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle

- •33. Problems Related to Mandibular Condylar Prosthesis

- •34. Reconstruction of Defects of the Mandibular Angle

- •35. Mandibular Body Reconstruction

- •36. Marginal Mandibulectomy

- •37. Reconstruction of Extensive Anterior Defects of the Mandible

- •38. Radiation Therapy and Considerations for Internal Fixation Devices

- •39. Management of Posttraumatic Osteomyelitis of the Mandible

- •40. Bilateral Maxillary Defects: THORP Plate Reconstruction with Removable Prosthesis

- •41. AO/ASIF Craniofacial Fixation System Hardware

- •43. Orbital Reconstruction

- •44. Nasal Reconstruction Using Bone Grafts and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •46. Orthognathic Examination

- •47. Considerations in Planning for Bimaxillary Surgery and the Implications of Rigid Internal Fixation

- •48. Reconstruction of Cleft Lip and Palate Osseous Defects and Deformities

- •49. Maxillary Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •50. Mandibular Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •51. Genioplasty Techniques and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •52. Long-Term Stability of Maxillary and Mandibular Osteotomies with Rigid Internal Fixation

- •53. Le Fort II and Le Fort III Osteotomies for Midface Reconstruction and Considerations for Internal Fixation

- •54. Craniofacial Deformities: Introduction and Principles of Management

- •55. The Effects of Plate and Screw Fixation on the Growing Craniofacial Skeleton

- •56. Calvarial Bone Graft Harvesting Techniques: Considerations for Their Use with Rigid Fixation Techniques in the Craniomaxillofacial Region

- •57. Crouzon Syndrome: Basic Dysmorphology and Staging of Reconstruction

- •58. Hemifacial Microsomia

- •59. Orbital Hypertelorism: Surgical Management

- •60. Surgical Correction of the Apert Craniofacial Deformities

- •Index

3

Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification

Craig R. Dufresne

Clinicians who study or treat individuals with congenital malformations of the head and neck realize that the spectrum of craniofacial malformations represents a relatively rare set of conditions that exist in a multitude of patterns and in varying degrees of severity. Over several years, many groupings of classifications have been put forth in an attempt to organize these conditions.1,2 Most either had been arbitrary or could not be standardized enough to be widely accepted because of extreme or bizarre distortions of the anatomy.3,4 Further confusion has arisen because there has not been any unanimity of terminology or satisfactory standardization of the classification of the innumerable craniofacial syndromes. At present, there are over 150 craniofacial syndromes, with new syndromes being described and published at the rate of 25 to 50 per year.5,6 Many specialties within the health profession have taken an interest in this task as the study of craniofacial malformations has developed into a multidisciplinary science. This diversity of focus and interest contributes to the difficulty in creating a generalized and acceptable approach to classifications.2 What appears to be an acceptable designation of a particular anomaly or anatomic defect for a geneticist or syndromologist may fall short for the craniofacial anatomist or surgeon.5–10 As human genetics and embryology become better defined and the etiologic factors at the gene and molecular level are studied, it is possible that a more exacting classification system will be devised.

Section A—Facial Clefting Incidence

The most common congenital facial anomaly is the cleft lip and palate. The frequency of its occurrence ranges from 0.60 to 2.13 per 1000 births.11,12 Sex, ethnic, and racial backgrounds influence the incidence of these anomalies. Blacks have been found to have the lowest incidence of cleft lip and palate, Caucasians are noted to have a higher incidence, and Asians have the highest incidence. Cleft lips with or without an associated cleft palate are seen more commonly in males.

Females, however, have a higher incidence of isolated clefts of the palate.5,6,10

Hemifacial or craniofacial microsomia (also known as the first and second branchial arch syndrome) is the next most frequent congenital facial anomaly. The frequency of this anomaly is estimated to be between 0.18 and 0.33 per 1000 births.5,10,13

The incidence of the remaining craniofacial anomalies is not well documented because of the very low rate of occurrence. A rough approximation of their frequency is in the range of 0.014 to 0.048 per 1000 births.5,6,14,15

Classified Schemas

The earliest classification schemas of the craniofacial malformations are often identified according to the names of the authors who first described them, such as Goldenhar, Pierre Robin, Treacher Collins, and Pfeiffer syndromes.3,4,15–18 Other malformations are identified by their descriptive appearance and have been given names such as hemifacial microsomia, retromandibulism, and hypertelorism without regard to their various causes. Other classifications are based on anatomic topography, with some authors dividing the face into various regions and others grouping the defects around the brain, sensory organs, or the branchial arch system. Ambiguities in terminology and multiple areas of overlap will be simplified to present an orderly development and working knowledge of this complex subject.1,4,5,9,10,15

Morian Classification

Morian is credited with the first attempt to classify craniofacial anomalies. In 1886, he described three types of facial clefts. The type I, or oronasal cleft, described a maxillary cleft located between the central and the lateral incisors extending into the nasal region. The type II, an oro-ocular cleft, described a maxillary cleft located between the incisor and the canine teeth that extends toward the orbit. The type III, also

22

3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification |

23 |

an oro-ocular cleft, described a maxillary cleft located behind the canine teeth that extends toward the orbit.5,6,14,15

Degenhardt Classification

Several subsequent classifications were attempted by such authors as Sanvenero-Rosselli, Burian, and others, but it was not until Degenhardt (in 1961) that a more complete, general category of craniofacial dysplasias were defined.5,6,14,16,18 Degenhardt describes four major groups of defects: (1) dysplasias in the region of the first and second branchial arches;

(2) dysplasias in the region of the premaxilla and the maxilla; (3) dysplasias of the soft tissues; and (4) craniofacial syndromes.5,14

Degenhardt’s first group of dysplasias of the first and second branchial archs contains two subgroups: (1) hypoplasias (including mandibular dysostosis, oculoauricular dysplasia, mandibulofacial dysostosis, oculomandibulofacial dysmorphia, oculomandibulofacial dyscephaly, and oculovertebral dysplasia); and (2) fusion anomalies (synechiae and syngnathia).5,6

In the second group, Degenhardt categorizes dysplasias of the premaxillary and maxillary regions, which are subdivided into hypoplasias and cleft formations. The hypoplasias included premaxillary hypoplasia (ankyloglossia superior syndrome) and premaxillary hypoplasias with other anomalies (anecephaly and anophthalmia). The cleft malformation subgroup includes cleft lip and palate with and without associated malformations, such as frontal encephalocele and arrhinia.5,6

Dysplasias of the soft tissue make up Degenhardt’s third major grouping. This is subdivided into lateral facial clefts, macrostomia, and astomia malformations.5

The fourth and last group under Degenhardt’s classification is a broad classification of craniofacial syndromes. This is subdivided into hypoplastic alterations in one region of the neural and visceral cranium (holoprosencephaly and aprosopia) and other characteristic syndromes, such as acrofacial dysostosis, dyscraniopygophalangy, and Crouzon’s disease.5,17,18

Lund Classification

The next major classification was presented by Lund in 1966. Lund attempted a more comprehensive approach to classify several craniofacial syndromes, particularly the ocular and cerebral syndromes. He developed five categories, attempting to separate cranial dysplasias from facial dysplasias, including several transitional forms, reduplications of the head region, and phakomatoses. The cranial dysplasias, Lund felt, are primary malformations at the base of the skull, occurring at the fifth to seventh week of embryological development. Facial dysplasias were considered to result from disturbances in the first and/or second visceral arches and their derivatives at the seventh week in utero.5,6,19

Lund’s theory considered most craniofacial dysplasias to be multifactorial in origin, with single gene expression play-

ing an insignificant role. He relied on the concept that specific “head organizers” located in the prosencephalic and rhombencephalic brain developmental regions explained the diverse combinations of eye, ear, face, skull, and brain abnormalities.15,19–21

American Association of Cleft Palate

Rehabilitation—Harkens Classification

In 1962, the American Association of Cleft Palate Rehabilitation (AACPR) attempted to standardize a classification for facial syndromes and clefts by endorsing a system proposed by Harkens and associates. These clefting syndromes are divided into four major groups: (1) mandibular process clefts;

(2) naso-ocular clefts; (3) oro-ocular clefts; and (4) oroaural clefts. The clefts of the mandibular process include clefts of the lip, mandible, and lip pits. The naso-ocular clefts extend from the alar region toward the medial canthus. The clefts of the oro-ocular group extend externally from the mouth toward the palpebral fissures and are subdivided into the oromedial canthal and orolateral canthal clefts. The latter group is on the temporal extension of the cleft from the lateral canthus. The last group of clefts, the oroaural clefts, extend from the mouth toward the ear.5,12,15

The classification, however, has several deficiencies, primarily because it is based on the surface anatomy and does not integrate the underlying craniofacial skeletal defects. It also fails to include major midline facial clefts or Treacher Collins syndrome.5,6,12–15,17,18

Boo-Chai Classification

Boo-Chai noted the deficiencies of the AACPR classification. In particular, Boo-Chai subdivided the description of the oroocular cleft into types I and II. The Boo-Chai types I and II clefts both bypass the nose and leave the piriform aperture intact, in contrast to the naso-ocular cleft. The infraorbital foramen was used to separate the two types of clefts.5,7,8,11,13,14,21 Morian was the first to distinguish and further describe the anatomic difference between the clefts and to note the importance of the infraorbital foramen.5,14

In the type I cleft, the soft tissue aspect of the upper lip differs from a common cleft lip in that it begins lateral to the Cupid’s bow. The cleft then courses lateral to the nasal alae into the nasoalar groove and ends as a coloboma in the midportion of the lower eyelid or, alternatively, at the lateral canthus. The bony element starts in the region of the bicuspids and courses lateral to the infraorbital foramen on its way to the inferolateral portion of the orbit.5

Tessier Classification

It was not until 1976 that Paul Tessier was able to present the first orderly anatomic classification system for all the established craniofacial clefting malformations.17 To simplify the

24

nomenclature of the clefts, Tessier devised a system in which a number is assigned to the site of each malformation, based on its relationship to the sagittal midline. The classification system is purely descriptive, however, and not related to the embryological development of the malformation or the underlying pathology. Nevertheless, this system has become widely accepted because of the ease of recording and simplicity of communicating the various malformations. It also has been found to correlate clinical appearance with practical surgical anatomy.17,18,22

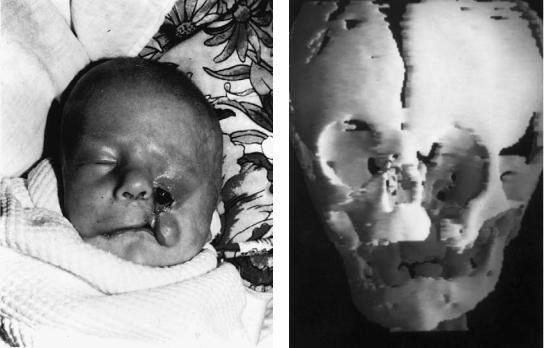

The facial clefts, according to Tessier, are basically orbitocentric in nature, distributing the involvement through the soft tissues of the face as well as the skeletal tissues of the maxilla, mandible, and neurocranium17 (see Figures 3.1 and 3.2) Clefts of the soft tissues and clefts of the craniofacial skeleton may not always exactly coincide; however, there exists an intimate relationship between the two structures. The orbit is the key structure for this classification schema. Its strategic location separates the cranial skeleton from the facial skeleton. A horizontal line can then be drawn through the canthi as an equator to divide the cranial and facial portions of the cleft. Tessier describes the clefting syndromes as developing according to constant axes, which are divided into 15 regions, or “time zones,” numbered 0 to 14 across and around the orbit. The facial clefts numbered 0 to 7 are found caudal to the orbital equator, and the clefts numbered 9 to 14 are found cephalad to the orbital equator. The No. 8 cleft coincides with the equator and passes laterally from the lateral canthus.17,18

C.R. Dufresne

FIGURE 3.1 The Tessier classification of craniofacial clefts are represented here as they appear through the bony framework of the skull. The system is based on an orbitocentric pattern with the facial component numbered from 0 to 7, with the exception of the mandible (midline mandibular cleft is designated as a No. 30 cleft). The cranial component of the clefts are numbered from 14 to 7 in a clockwise pattern. The axial pattern when added together totals 14 for the complete form of the cleft as it traverses through the facial to the cranial area.

FIGURE 3.2 The Tessier classification of craniofacial clefts is shown here as they appear through the soft tissues of the face. They follow the same patterns as that of the bony clefts with the same designation and numbering.

3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification |

25 |

The facial clefts and the cranial clefts can occur independently of each other or in combination to form a craniofacial cleft. Although bilateral representatives of craniofacial clefts occur, unilateral forms are more common. Multiple craniofacial clefts are also seen in the same individual and have long been associated with certain syndromes. They need not be symmetric or of equal severity. Because the cranial and facial clefts tend to follow the same axis, Tessier incorporated this concept as the keystone of his classification. Its importance lies in the analysis and examination of the patient. This concept forces the clinician to look up and down the axis and neighboring zones, resulting in the possible discovery of unexpected or overlooked malformations.

Clefts of the soft tissues and clefts of the craniofacial skeleton may not always coincide in severity. The extent of involvement of each component is often quite variable, and as a rule, the bony deformation is greater in the facial clefts. Conversely, in clefts medial to the infraorbital foramen, the defect of the soft tissue tends to be generally greater (with the exception of cleft No. 3).17,18

The Nos. 0 to 14 clefts of Tessier are median craniofacial dysraphia (Figure 3.3). This is probably secondary to a defect of closure of the anterior neuropore. The cleft involves the frontal bone resulting in a median encephalocele, the ethmoid region (creating a duplication of the crista galli), the nose (resulting in duplication of the septum and columella), and finally, the maxilla and lip. Intraorally, a diastema separates the central incisors, whereas the palate itself can be cleft through the midline. The No. 0 cleft usually results in hypertelorism, whereas if agenesis or hypoplasia is the predominant malformation, a partial or total absence of the philtrum and the premaxilla can occur. The nose can be flat, side, small, and lacking a columella. The nostrils are intact and laterally displaced. A midline groove in the columella and nasal tip, resulting in a bifid nose, is seen. At the other extreme, a proboscis or arrhinencephaly can be seen with the resultant orbital hypotelorism, cebocephaly, or cyclopia.17,18

Prolongation of the No. 0 cleft or No. 30 cleft of Tessier onto the mandible could be represented in its most minor form as a notch in the lower lip, and it can become progressively more severe by involving the mandible, tongue, chin, neck, hyoid bone, and even the sternum. The tongue is frequently bifid and bound to the mandible by a dense band of tissue. The cleft of the alveolus is located in the midline passing between the central incisors.

The Tessier No. 1 cleft is a paramedian, craniofacial cleft that traverses through the soft tissues from the cupid’s bow region to the dome of the alar cartilage, resulting in a notch in the dome of the nostril extending to the medial aspect of the eyebrow. If the No. 1 cleft extends more superiorly onto the frontal bone, it is referred to as the No. 13 cleft. The olfactory groove of the cribiform plate becomes widened, resulting in hypertelorism. The groove or cleft then passes between the nasal bone and the frontal process of the maxilla.

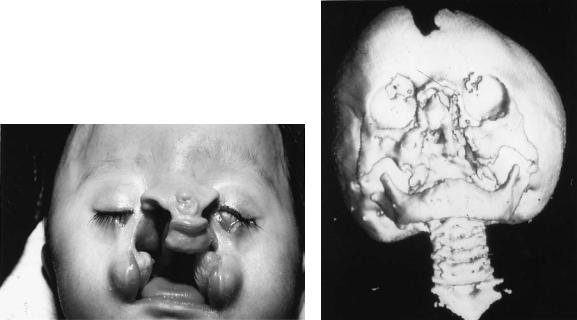

FIGURE 3.3 An example of a infant with a Tessier No. 0 to 14 facial cleft with the midline cleft lip and palate, hypertelorism, agenesis of the midline nasal structures, absence of the premaxilla and philtrum, underlying cranial base defect, and encephalocele.

Inferiorly, the No. 1 cleft continues through the alveolus between the central and lateral incisors.14,17,18

The Tessier No. 2 appears identical to the No. 1 cleft, but it is actually more lateral in a paranasal location. There is some question of whether this a true entity of a transitional form between clefts No. 1 and No. 3. It traverses the soft tissue of the nose between the summit and the base of the alar cartilage and then onto the lip. The palpebral fissure is not involved in this cleft. Distortion of the eyebrow occurs just lateral to its medial end point as the cleft continues into the frontal region as a No. 12 cleft of Tessier. The location of the eyebrow coloboma distinguishes this cleft from neighboring clefts. The bony facial skeletal component of this cleft crosses the alveolus in the region of the lateral incisor. The nasal septum remains intact, but it may be distorted by surrounding malformations. Septation is present between the nasal cavity and the maxillary sinus, and notching is seen near the junction of the nasal bone with the frontal process of the maxilla. The nasolacrimal system is not disturbed as in the No. 3 cleft. Enlargement of the ethmoidal labyrinth results in orbital hypertelorism. Usually, the glabella is flattened and the frontal sinus is enlarged. The Tessier No. 12 cleft is the cranial equivalent of the Tessier No. 2 facial cleft.14,17,18

26

Tessier believes that nasal hemiatrophy, supernumerary nostrils, and proboscis lateralis are probably different degrees and forms of the same paracentral defect. These malformations may be associated with clefts No. 2 and No. 3 because of malformations in the ethmoidal labyrinth and the lacrimal apparatus.

The Tessier No. 3 cleft is a medial orbitomaxillary cleft that extends through the bony skeleton as a paranasal cleft traversing obliquely across the lacrimal groove. The frontal process of the maxilla as well as the medial wall of the maxillary sinus is often completely absent. The cleft lies in the area of the embryological union of the medial nasal, lateral nasal, and maxillary processes. The cleft is believed to result from a lack of fusion, insufficient mesodermal penetration, or failure of the nasolacrimal system. Through the soft tissue, the cleft passes across the lacrimal segment of the lower eyelid around the alar base into the nasolabial fold and traverses the lip and alveolar ridge (Figures 3.4a,b).17,18

The lip and palate deformities associated with the Tessier No. 3 cleft are located in the same region as the common clefts of the lip and palate in the Tessier No. 1 and No. 2 clefts. In the nasal area, the Tessier No. 3 cleft changes course and passes through the base of nasal ala. The mildest form of this cleft is represented by a coloboma of the nasal ala. The resultant defect can manifest itself as a distortion or absence of the frontal process of the maxilla. The vertical distance between the alar base and the medial canthus is disturbed, and the nasolacrimal duct is obliterated. Malformations of the oc-

C.R. Dufresne

ular region are usually characteristic of this cleft and include dystopia of the medial canthus, colobomas of the lower eyelid medial to the punctum, and hypoplasic, inferiorly displaced medial canthal tendons. Ocular involvement is variable and may be represented as microphthalmia in its severest forms. The Tessier No. 11 cleft represents the more superior, or “northbound,” extension of the cleft into the medial third of the upper eyelid and eyebrow and then onto the forehead.14,17,18

The Tessier No. 4 cleft is a median orbitomaxillary cleft that traverses through the soft tissue Tessier No. 4 cleft almost vertically to involve the inferior eyelid; medial to the punctum, the infraorbital rim; and the floor of the orbit, medial to the infraorbital nerve. The cleft continues onto the lip between the philtral crest and the commissure. Superiorly, the superior portion continues into the medial third of the eyelid and eyebrow. As a result of the lateral location of the cleft, the nasolacrimal canal and lacrimal sac remain intact. The medial canthal tendon appears almost normal with respect to its direction and insertion. In the most severe forms, the range of anomalies can culminate in the development of anophthalmia. The cleft on the anterior surface of the maxilla passes medial to the infraorbital foramen and produces a bony defect in the medial portion of the inferior orbital rim and floor. The contents of the orbit may tend to settle into this fissure, resulting in orbital dystopia. In the complete form of the cleft, the orbital cavity, maxillary sinus, and oral cavity are all confluent. Posterior nasal choanal atresia is often associated with the defor-

a |

|

|

|

|

|

b |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 3.4 (a) This young Asian child exhibits a bilateral form of a Tessier No. 3 to 11 cleft with skin bridges along the lower eyelids, but with evidence of medial eyelid hypoplasia, lacrimal system involve-

ment, and medial maxillary hypoplasia. (b) The skeletal involvement runs parallel to the soft tissue clefts and is evident as bony defects along the medial maxilla, palate, orbital floors, and cranial base.

3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification |

27 |

mity. In bilateral cases, the nose appears smaller than normal, and the premaxilla is protruded. On the upper facial bony skeleton, the Tessier No. 10 cleft corresponds to the superior extension of the Tessier No. 4 facial cleft (Figures 3.5a,b).17,18 The Tessier No. 5 cleft is the rarest of the oblique facial clefts. This cleft also corresponds to the oculofacial II cleft and Morian III cleft. The cleft of the lip is found just medial to the angle of the mouth but not at the commissure itself. It courses upward across the lateral cheek to and between the medial and lateral thirds of the eyelid. The vertical distance between the mouth and the lower eyelid is decreased, resulting in a pulling of the upper lid and lower eyelid toward each other. Microphthalmia is infrequently present. The bony skeletal malformation parallels the path of the cleft. The alveolar portion of the cleft now begins posterior to the cuspid, and it is found in the premolar region. Passing lateral to the infraorbital foramen, the cleft enters the orbit through the inferolateral part of the orbital rim and floor. The orbital contents may prolapse into this gap and, therefore, into the max-

illary sinus.17,18

Tessier No. 6 cleft is characteristically recognized as the incomplete form of the Treacher Collins’ syndrome. The external ears can be normal or almost normal, but a hearing deficit is often present. The antimongoloid slant of the palpebral fissures is milder, but the coloboma of the lower eyelid

occurs at the usual medial third locations. The bony malformations of this cleft has set it apart from the complete form of the syndrome. In this cleft, the malar bone is present, but hypoplastic with an intact zygomatic arch. The cleft runs between the hypoplastic malar bone and the maxilla in the region of the zygomaticomaxillary suture.17,18

The Tessier No. 7 cleft is the most common and probably the earliest recorded craniofacial cleft, having been found in the cuneiform inscriptions by the Chaldeans of Mesopotamia in 2000 B.C. The No. 7 cleft is also synonymous with multiple other anomalies, including necrotic facial dysplasia, hemifacial microsomia and microtia, otomandibular dysostosis, unilateral facial agenesis, auriculobranchiogenic dysplasia, intrauterine facial necrosis, hemignathia and microtia syndrome, lateral facial clefts, transverse facial clefts, and oro- mandibular-auricular syndrome. Goldenhar’s syndrome is also comparable in many of its features, but it also involves epibulbar cysts and vertebral anomalies.17,18

The clinical expression of this cleft varies from a slight facial asymmetry with minimal auricular malformations to severe malformations of the external auditory canal and the middle ear ossicles. Tessier believes the cleft is centered in the region of the zygomaticotemporal suture.14,17,18 Hypoplasia of the maxilla, temporal bone, soft palate, and tongue has been seen. The parotid gland and duct can be absent, along with

a |

|

b |

|

FIGURE 3.5 (a) A newborn infant with a Tessier No. 4 to 10 cleft on the left and Tessier No. 7 cleft on the right side of the facial structures. (b) The facial and lower eyelid tissues are very hypoplastic on the left, and the palate is cleft in line with the soft tissue cleft. There is widening of the right commissure and a soft tissue deficiency run-

ning along the axis of the facial cleft to the right ear. There is a left vertical dystopia and flattening of the frontal bone and hypoplasia of the cranial base noted on the CT scan corresponding to the bony skeletal cleft.

28

portions of the mandible and zygoma. The fifth and seventh nerves can be involved along with their innervated musculature, represented by weakness of the muscles of mastication (first branchial arch structures and trigeminal nerve) and muscles of facial expression (second branchial arch structures and facial nerve). As a result of the hypoplastic maxilla and the reduced height of the mandible ramus, there is a cephalad cant to the occlusal plane on the affected side. In the complete form, the mandibular condyle and ramus can be missing. There may only be a soft tissue ear tag or a soft tissue cleft extending from the corner of the mouth toward the ear. As a result of the hypoplasia of the zygoma, there may be drooping of the superolateral angle of the orbit with lateral canthal dystopia.

The Tessier No. 8 cleft corresponds to the temporal continuation of the orolateral canthus cleft of the AACPR classification and the commissural clefts of the ophthalmo-orbital malformation of Karfik.20 The isolated form of the No. 8 cleft is rarely seen. The soft tissue cleft begins at the lateral commissure of the palpebral fissure and extends toward the temporal region. The lateral coloboma can be occupied by a dermatocele. The bony elements of the cleft lie in the region of the frontozygomatic suture. When combined with the No. 6 and No. 7 clefts, the zygoma is absent.5,14,16–18

Tessier has noted a unique bilateral combination of clefts No. 6, No. 7, and No. 8.5,14,15,17,18 This combination is best demonstrated by the malformation known as Treacher Collins syndrome, Franceschetti-Zwahlen-Klein syndrome, or mandibulofacial dysostosis. The hallmark of this syndrome is the absent malar bone, which is the result of these clefts of the maxillozygomatic, temporozygomatic, and frontozygomatic sutures.

Soft tissue malformations associated with the No. 6 cleft result in a coloboma of the lower eyelid and deficiency or absence of the medial two thirds of the eyelashes. The infraorbital neurovascular bundle frequently exits the orbit and goes directly into the subcutaneous tissues. The No. 7 cleft results in the absence of the zygomatic arch, fusion and hypoplasia of the masseter and temporalis muscles, otic malformation (resulting in conductive hearing loss), medial displacement of sideburns, microtia, and mandibular deficiencies. Since the characteristic underlying deformity of the complete form of the syndrome is the absence of the zygoma, the lack of bony support results in the eyelid coloboma and the antimongoloid slant of the palpebral fissure. The No. 8 cleft results in the absence of the lateral orbital rim with associated lateral canthal dystopia. The abnormal configuration of the masseter muscle and temporalis muscle results in changes in the mandible. The vertical dimension of the ramus is foreshortened, producing a retrognathic mandible with an open bite. Microgenia and the accentuated mandiblar notch represents the lower third of the facial deficit. This complex of malformations completes the typical facies of the syndrome.5,17,18

The Tessier No. 9 cleft is a superolateral orbital cranial cleft traversing the lateral third of the upper eyelid and superolat-

C.R. Dufresne

eral angle of the orbit. It is the first of the “northbound” cranial counterparts of the facial clefts. This cranial cleft (No. 9) seems to correspond to facial cleft No. 5, but both are rare. The cleft is centered in the superolateral angle of the orbit. This disrupts the orbital rim as the cleft continues into the frontotemporal cranium.17,18

The Tessier No. 10 cleft is a central superior orbital cleft located at the medial third of the supraorbital rim, lateral to the supraorbital nerve. It extends across the roof of the orbit and the frontal bone. The midportion of the bony orbital rim and the adjacent orbital roof and frontal bone are cleaved. A fronto-orbital encephalocele is often found in this area and results in a laterally and inferiorly rotated orbit. The soft tissue deformity is characterized by the coloboma of the medial third of the upper eyelid and can occur as a total lack of eyelids in its severest form. The eyelid and eyebrow are divided into two portions, the lateral portion being vertical and joining the scalp hairline and the medial portion being atrophic or occasionally absent. The No. 10 cleft appears to be the more superior cranial equivalent of facial cleft No. 4 with both clefts possibly having a coloboma of the iris.17,18

The Tessier No. 11 cleft is a superomedial orbital cleft. The coloboma of the medial third of the upper eyelid sometimes extends to the eyebrow and can extend into the frontal hairline. The skeletal malformations of this cleft have not been identified but seem to be the cranial equivalent of facial cleft No. 3. The cleft can pass lateral to the ethmoid bone and result in a cleft in the medial third of the eyebrow and orbital rim, or it can take an alternative pathway through the ethmoid labyrinth, resulting in orbital hypertelorism.17,18

The Tessier No. 12 cleft is located medial to the medial canthus passing through the frontal process of the maxilla and the nasal bone. This flattening results in telecanthus. The ethmoidal labyrinth is increased in transverse dimensions, resulting in orbital hypertelorism. The cleft passes across the lateral mass of the ethmoid and frontal bone lateral to the cribriform plate and olfactory groove. The cleft in the soft tissues extends from the root of the eyebrows and into the frontal hairline. The cranial equivalent of the No. 12 cleft is facial cleft No. 2.17,18

The Tessier No. 13 cleft corresponds to the cranial extension of the No. 1 cleft of the face. The distinctive feature of this malformation is the widening of the olfactory grooves and cribriform plate, resulting in hypertelorism. The cribriform plate can be displaced inferiorly by the paramedian frontal encephalocele. The severest forms of orbital hypertelorism can result from the bilateral forms of this cleft, when the ethmoid labyrinth is enlarged and extensive pneumatization of the frontal sinus exists. The eyelids and eyebrows are displaced laterally by the cleft. Another distinct feature of the cleft is an omega-shaped disruption of the hairline away from the midline.17,18

The Tessier No. 14 cleft, unlike the No. 0 cleft, is always associated with hypertelorism. The embryological malformation is attributed to the formation of the nasal capsule. As a

3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification |

29 |

result of the morphokinetic arrest of the movement of the eyes, the orbits tend to remain in the widespread fetal position. The result is a cranium bifidum or displacement by a large medial frontal encephalocoele. The crista galli is widened or duplicated, and the distance between the olfactory grooves is increased. The ethmoid bone prolapses caudally because of the increased intraorbital space. The frontal bone flattens and the glabella appears indistinct.17,18

This completes the axial dysplasias of the craniofacial syndromes proposed by Tessier. At present, this is the most widely accepted and used classification among craniofacial surgeons.

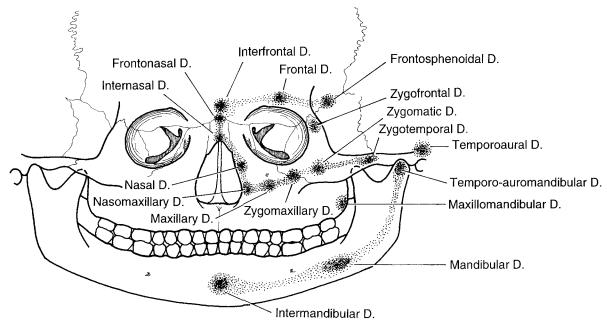

Van der Meulen et al. Classification

In recent years, a group of European plastic surgeons proposed a redefinition of terms and a new classification to facilitate communication among specialties. This schema also attempted to avoid confusion among the craniofacial syndromes and embryological pathophysiology. Their classification respresents the collective experience of five craniofacial surgeons (van der Meulen, Mazzola, Vermey-Keers, Stricker, and Raphael) working in three different countries (Netherlands, France, and Italy) (Table 3.1).23

The van der Meulen et al. schema proposes that instead of a clefting syndrome in the area of the malformation, there is actually a form of “dysplasia.” Embryologically, regardless of the cause, an arrest of tissue (skin, muscle, or bone development) manifests itself as a “focal fetal dysplasia.” The ultimate appearance and severity of the dysplasia depends on the localization of the area(s) involved and the time at which the disturbance of developmental arrest occurs (Figure 3.6).24

The van der Meulen et al. classification, the most recent of the new classifications, attempts to associate the clinical presentations of the craniofacial anomalies with the pathology arising from the maldevelopment at the embryological level. Their proposed craniofacial developmental helix is useful in relating the clinical and embryological anomalies. New terminology has also been introduced to explain the morpholopathogenesis, but at present, this has only begun to be analyzed and standardized.5,6,23

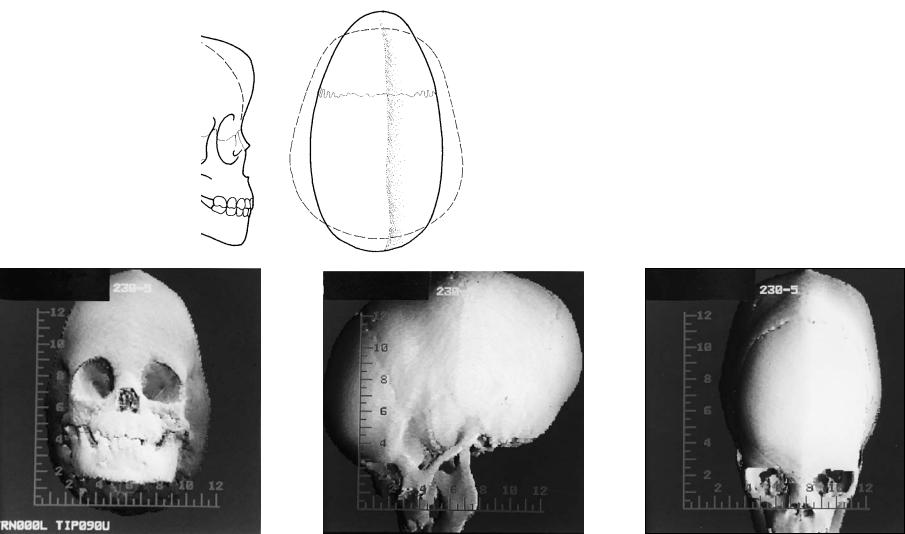

Section B—Craniosynostosis

A second major group of congenital malformations that has been alluded to several times during the discussion of previous craniofacial classifications is the craniosynostosis anomalies. These deformities are not the result of a cleft but a premature closure of one or more of the cranial sutures. The severity of the resultant deformity is directly proportional to the area of suture involved (Figures 3.7–3.10). The range of facial deformation can be minimal, as a ridge along the sagittal suture or as in a mild trigonocephaly deformity, with the premature closure of the metopic suture, to severe, as in the

TABLE 3.1 Van Der Meulen et al. classification.

Cerebral Craniofacial Dysplasia

Interophthalmic dysplasia

Ophthalmic dysplasia

Craniofacial Dysplasia

Dysostoses

Frontosphenoid dysplasia

Frontal dysplasia

Frontofrontal dysplasia

Frontonasoethmoid dysplasia

Internasal dysplasia

Nasal dysplasia

Type 1—nasal aplasia

Type 2—nasal aplasia with proboscis

Type 3—nasoschizis

Type 4—nasal duplication

Nasomaxillary dysplasia

Maxillary dysplasia

Medial maxillary dysplasia

Lateral maxillary dysplasia

Maxillozygomatic dysplasia

Zygomatic dysplasia

Zygofrontal dysplasia

Zygotemporal dysplasia

Temporoaural dysplasia

Zygotemporoauromandibular dysplasia

Temporoauromandibular dysplasia

Maxillomandibular dysplasia

Mandibular dysplasia

Intermandibular dysplasia

Craniofacial Synostoses

craniofacial dysostosis syndromes as in Crouzon’s syndrome or Kleeblatschädel deformity in which multiple sutures are involved (Figure 3.11).1–5,7,8,25,26

Virchow, in 1851, was the first to coin the term craniosynostosis and presented an attempt to develop an organized classification system.4 The word craniosynostosis has been used recently to describe the process of premature fusion, with craniostenosis being the result. At present, the terms are interchangeable. There are several different types of craniosynostosis (Table 3.2). Craniosynostosis may be either simple or compound. The simple form refers to the involvement of the suture being prematurely fused, whereas the compound form involves synostosis of two or more sutures.1,3–5

Craniosynostosis may also be designated as either a primary or secondary type. In primary craniosynostosis, the sutures prematurely fuse as a result of a genetic predisposition. In secondary craniosynostosis, suture closure is secondary to a known disorder, such as one of certain hematologic disorders (thalassemic), metabolic disorders (hyperthyroidism), and/or malformations (e.g., microcephaly).4

The last category defining craniosynostosis involves separation into isolated or syndromic forms. The isolated craniosynostosis form is present in patients who have no other abnormalites except those that occur secondarily to premature suture obliteration, such as neurologic or ophthalmologic manifestations. Syndromic craniosynostosis occurs in patients with other primary defects of morphogenesis (as in Carpen-

30

FIGURE 3.6 The van der Meulen et al. classification uses an S-shaped configuration to represent the embryological development and malformations in the craniofacial helix starting at the lateroposterior wall of the orbit to the lower face. The upper half of the helix encircles the orbit while the lower half encircles the mouth. The dysplasias in

ter’s syndrome, where polysyndactyly and congenital heart defects accompany the craniosynostosis).4,5

Three theories have been proposed for the pathogenesis of craniosynostosis. The first theory, proposed by Virchow, maintained that craniosynostosis was the primary event and the associated cranial base deformity was secondary to the craniosynostosis. The converse of this theory was proposed by Moss, who postulated that the cranial base malformation was the primary anomaly, resulting in secondary premature closure of the cranial sutures. A third theory postulates a primary defect in the mesenchymal blastema that results in both craniosynostosis and an abnormal cranial base.4,21,25,27

Regardless of the primary event, the calvarium reflects the results of a rapidly expanding brain. With a prematurely closed suture, the calvarial growth becomes inhibited in a perpendicular direction to the closed suture. This results in a compensatory overexpansion and growth in the areas of the normal sutures to accomodate the growth of the brain. Since the midfacial structures are attached to the undersurface of the cranial vault, alterations in the growth of the anterior cranium will be reflected on the developing face. The alterations can be unilateral, as in the distortion seen by the premature closure of a hemicoronal suture (plagiocephaly), or bilateral malformations, such as craniosynostosis of the metopic or sagittal sutures or coronal sutures that can also result in severe midfacial retrusion (Crouzon’s syndrome).

Various estimates of the incidence of simple craniosynostosis have been made in the literature. The range extends from

C.R. Dufresne

the upper half of the S may be associated with ocular and periocular malformations, clefts, or hypoplasias, while dysplasias of the lower helix are associated with clefts, malformations, preauricular tags, pits, and fistulas.

0.4/1000 births to 1.6/1000 births. The former value is considered the most accurate estimation.1,2,5,10

Virchow’s Classification

Historically, as in attempts at facial clefting classification, many attempts have been made to group various characteristics into an organized pattern. These categorizations have reflected the current knowledge, interests, and experience of the classifier. Virchow, in 1851, was the first to classify head shape based on specific sites of cranial suture synostosis as he observed from the examination and measurement of preserved skulls and not on clinical experience (Table 3.3). He also made an attempt to deal with partial synostosis as well as with involvement of the cranial base. This anatomic classification was abandoned in time because of the numerous narrow categories and as more was learned about the dynamics of craniosynostosis.4–6

Simmons-Peyton Classification

Another proposed classification was put forth by Simmons and Peyton in 1947, in an attempt to present a simple and useful system for the clinician (Table 3.4). Their objective was to establish important groupings, minimize duplicated terminology and disregard insignificant narrow or minor varia-

tions.5,14,15

a |

|

b |

|

|

|

c |

d |

e |

FIGURE 3.7 (a,b) The scaphocephaly deformity can arise secondary to sagittal craniosynostosis. This presents as generalized elongation and narrowing of the cranium. This also results in a temporal constriction and often a ridging that occurs along the involved sagittal suture. Bossing is noted both anteriorly and posteriorly in the cranium beyond the normal

configuration of the cranium noted by the dotted line. (c,d,e) CT scans demonstrate the threedimensional cranial contour of the skull with ridging along the course of the obliterated sagittal suture.

31

32

a |

b |

c |

|

|

|

d |

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

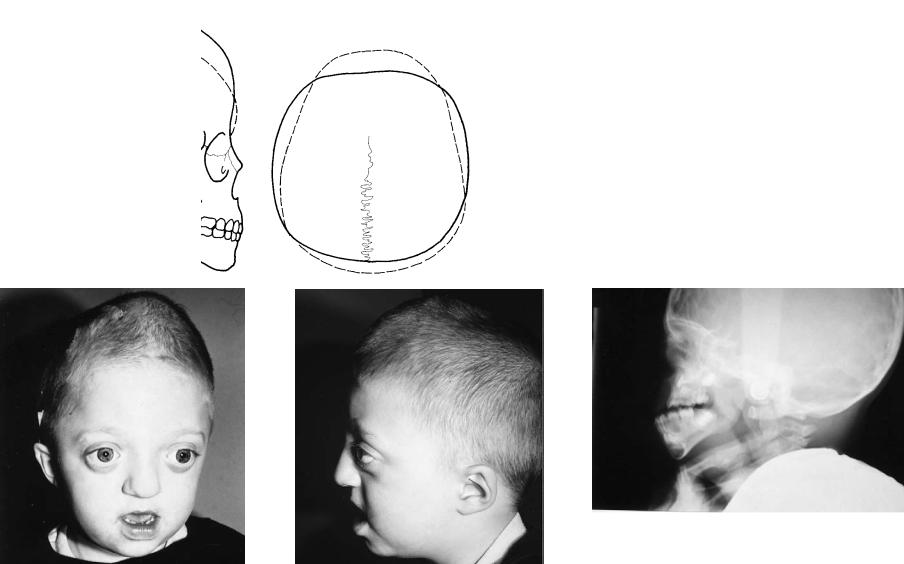

FIGURE 3.8 (a,b) Bicoronal craniosynostosis can be seen in Crouzon’s disease and craniocephalic disorders of Karfik-Group D. This represents a typical patient with bilateral coronal synostosis and a “tower skull” deformity with increased cranial height and overincrease in the width of the skull. (c,d,e) Severe midfacial retrusion is also often evident in these pa-

tients since the cranial base is often involved. The head is often wide with a decreased anterior posterior dimension (brachycephaly) as in this young child with Crouzon’s syndrome demonstrating intracranial “thumbprinting” and class III malocclusion.

a |

b |

c |

d |

e |

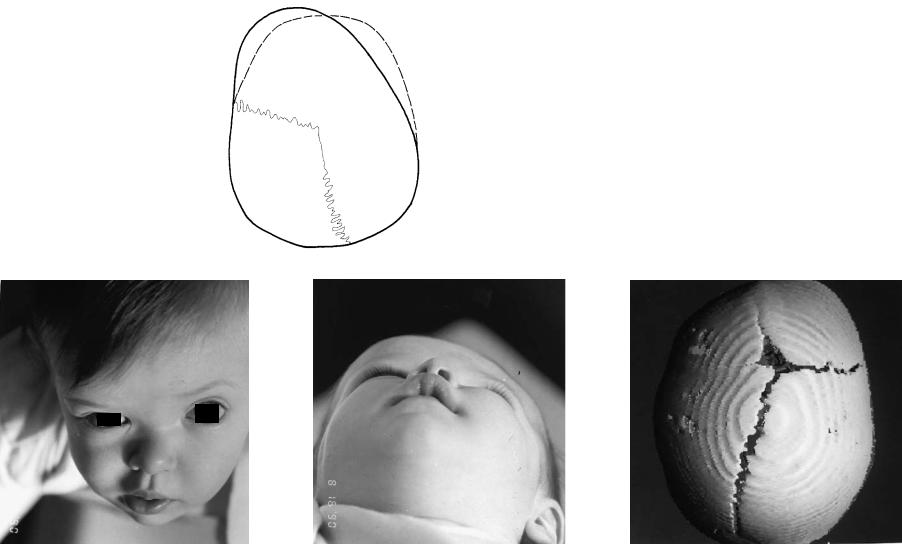

|

FIGURE 3.9 (a,b) Unilateral coronal synostosis results in a plagiocephaly deformity. In this figure, the affected right frontal area is foreshortened, the contralateral frontal area is bossed anteriorly. There is periorbital distortion along the right roof of the orbit and asymmetry around the orbital walls, sphenoid wing, and anterior cranium. (c,d) This clinical example is a young

girl with left coronal craniosynostosis. Note the flattening of the left frontal area and supraorbital rim. (e) The CT scan reveals the underlying bone deformity with patency of all the cranial sutures except for the left coronal.

33

a |

b |

c |

|

|

d |

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

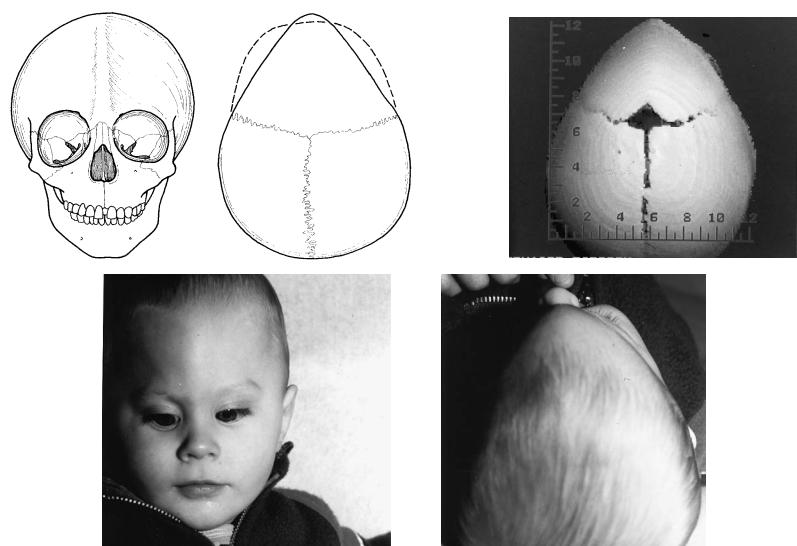

FIGURE 3.10 (a,b) Premature closure of the metopic suture results in a secondary trigonocephaly deformity. This results in a triangular deformity of the frontal bone with central frontal bossing (keel) and constriction of the temporal areas. (c,d) The young boy reveals

the same deformity as well as a degree of orbital hypotelorism. (e) The CT scan reveals the patency of the other cranial sutures with the anterior triangular cranial deformity.

34

3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification |

35 |

||

|

TABLE 3.2 Types of craniosynostosis. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Type |

Definition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Simple |

One suture involved with craniosynostosis |

|

|

Compound |

Two or more sutures are involved with craniosynostosis |

|

|

Primary |

Craniosynostosis of cranial sutures being the isolated |

|

|

|

problem or process |

|

|

Secondary |

Craniosynostosis secondary to a known metabolic or |

|

|

|

hematologic disorder |

|

|

Isolated |

Craniosynostosis is the principal problem or deformity |

|

|

Syndromic |

Craniosynostosis associated with other primary defects |

|

|

|

of morphogenesis |

|

|

|

|

|

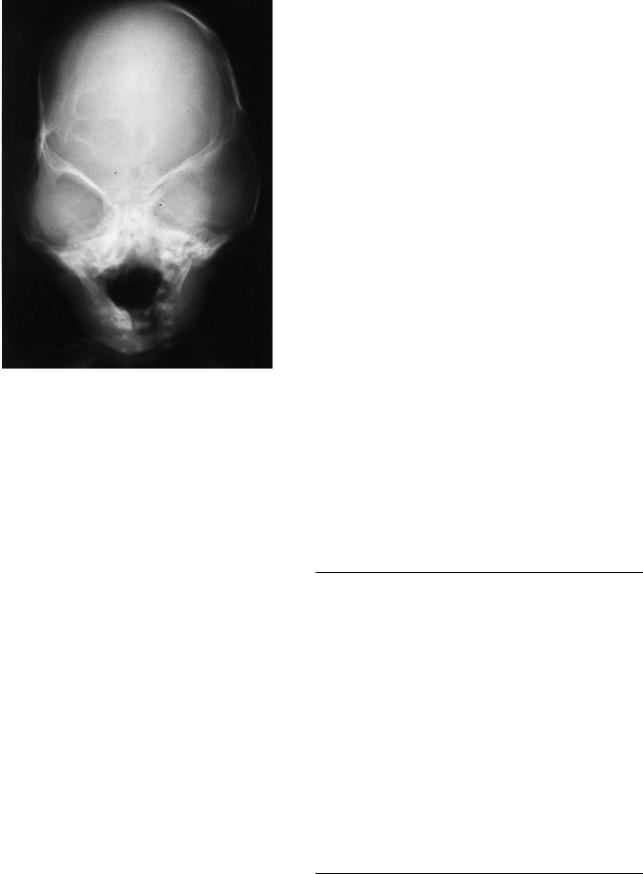

FIGURE 3.11 The Kleeblatschädel deformity is characteristically a trilobed cranial deformity as reflected in this case. Multiple cranial sutures are involved and severely increased intracranial pressure is evidenced by the cranial “thumbprinting.”

Cohen Classification

As with the complex variety of clefting syndromes, the craniosynostosis syndromes present a formidable challenge to the embryologist, geneticist, anatomist, and the surgeon. Cohen, in an effort to categorize and describe these anomalies, proposed three specific classifications based on clinical similarities, anatomy, pathogenesis, and genetic transmission (Tables 3.5–3.7).1–5

Tessier Classification

Tessier, in 1981, because of his vast clinical experience put forth a classification based on involved anatomy and topography related to the craniosynostosis as well as other associated facial anomalies (Table 3.8).25,26 This classification is practical for the clinician and surgeon because the craniofacial conditions are grouped for surgical purposes. Even though their genetic classification and ethiology may be different, their pathogenesis and phenotypes may be very similar. Due to the limitation of this text, a brief discussion of some of the common types of craniosynostosis syndromes will be presented.

Crouzon’s syndrome is one of the most common and best known malformations characterized by premature synostosis of the coronal suture and, at times, the sagittal-lambdoidal sutures. The deformity results in a foreshortened cranial base

and a retropositioned frontal bone. The midface is hypoplastic and retruded, and the orbits are shallow, resulting in exorbitism. Mild hypertelorism is also part of the syndrome. Clinically, the appearance is one of psuedomandibular prognathism. If the exorbitism is severe, exposure keratitis can result. The retropositioned soft palate fills the oral and nasal pharynx and may result in airway obstruction. Intelligence is usually normal; however, if the malformation is severe, an increase in intracranial pressure can result, with concomitant secondary effect on cerebration and vision.25,26

Apert’s syndrome, or acrocephalosyndactyly, is an anomaly in which the calvarium has a short, broad, tower-like appearance (turribrachycephaly). The coronal sutures are prematurely synostosed, but the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures can contribute to the deformity. The face has a high, flat forehead with a transverse ridge in the supraorbital region. The occipital bone is flattened, which contributes to the brachycephalic appearance. The exorbitism is milder than that seen in Crouzon’s syndrome, although there is a greater degree of hypertelorism. Divergent strabismus and exophoria are also present along with some degree of mental retardation. The

TABLE 3.3 Virchow’s classification.

I. Simple macrocephaly (hydrocephaly)

II. Simple microcephaly

III.Dolichocephaly (long-headedness)

A.Upper central synostosis

1.Dolichocephaly (sagittal synostosis)

2.Sphenocephaly (sagittal synostosis with protruding bregma)

B.Lower lateral synostosis

1.Leptocephaly (sphenofrontal synostosis)

2.Clinocephaly (sphenoparietal or temporal synostosis)

C.Fetal synostosis of the frontal suture

1.Trigonocephaly (metopic synostosis)

IV. Brachycephaly (short-headedness)

A.Posterior synostosis

1.Pachycephaly (lambdoidal synostosis)

2.Oxycephaly (lambdoidal and temporoparietal synostosis with protruding bregma)

B.Upper anterior and lateral synostosis

1.Platycephaly (coronal synostosis)

2.Trochocephaly (partial coronal synostosis)

3.Plagiocephaly (unilateral coronal synostosis)

C.Lower central synostosis

1.Simple brachycephaly (cranial base synostosis)

36

TABLE 3.4 Simmons-Peyton classification.

A.Complete, early premature synostosis of the cranial sutures (oxycephaly, turricephaly)

1.Oxycephaly without facial deformity

2.Craniofacial dysostosis of Crouzon

3.Acrocephalosyndactylism

4.Delayed oxycephaly (onset after birth)

B.Incomplete early synostosis of the cranial sutures

1.Scaphocephaly (premature closure of the sagittal suture)

2.Brachycephaly (premature closure of the coronal sutures or to the coronal and lambdoidal sutures)

3.Plagiocephaly (asymmetric premature sutural closure)

4.Mixed

C.Late premature synostosis of cranial sutures after skull has reached nearly adult size so that no deformities and no symptoms result (i.e., nonpathologic requiring no surgical intervention).

midface, again, is hypoplastic with the resultant pseudomandibular prognathism. Clefts of the soft palate occur in approximately one third of the patients, but invariably, a higharched constricted palate is present. The anomaly of the hands and the feet in Apert’s syndrome is symmetric syndactyly of both the hands and the feet, particularly in the middle three digits.24,25

The facial features of the Pfeiffer syndrome resemble those of the previously described craniosynostosis syndromes. The coronal suture is the primary site of premature synostosis, resulting in the typical hypoplastic midface with a turribrachycephalic calvarium. The hypertelorism and exorbitism are mild, and the intelligence is normal. The hallmark of the syndrome is manifested by the digitial anomalies, again with

TABLE 3.5 Cohen’s anatomic classification of craniosynostosis.

Name |

Premature sutural synostosis |

Simple synostosis |

|

Brachycephaly |

Coronal suture |

Dolichocephaly |

Sagittal suture |

(scaphocephaly is also used |

|

interchangeably) |

|

Trigonocephaly |

Metopic suture |

Pachycephaly |

Lambdoidal sutures |

(this term is neither well |

|

known nor well accepted) |

|

Plagiocephaly |

Unilateral coronal or unilateral |

(some associate this term |

lambdoidal |

only with unilateral coronal |

|

synostosis) |

|

Compound synostosis |

|

Acrocephaly |

All sutures |

(oxycephaly is also used |

|

interchangeably with this term; |

|

some define acrocephaly as |

|

synostosis of the coronal suture |

|

plus one other suture) |

|

Kleeblattschädel, and |

Clover-leaf skull deformity and |

other terms |

other combinations of suture |

|

involvement that lead to |

|

characteristic shapes |

|

|

|

C.R. Dufresne |

TABLE 3.6 Cohen’s anatomic/genetic perspectives. |

|

|

|

Anatomic perspective |

Genetic perspective |

|

|

Specific suture synostosed |

Specific suture synostosed |

of primary importance |

of secondary importance |

Clinical description |

Overall pattern of anomalies |

Growth and development |

Which family members are affected |

Surgical management |

|

|

|

the thumb and the great toe being broad and directed in a varus direction.

In the Saethre-Chotzen syndrome, again, an acrocephalic configuration of the cranium is present as a result of premature synostosis of the coronal suture. However, the midfacial hypoplasia is not a feature of this anomaly. The face is asymmetric with deviation of the nasal septum and with the orbits at unequal levels. The frontal hairline is low set with upper eyelid ptosis often present. The nose appears beaked, or there appears to be an absence of the frontonasal angle. The extremity anomalies associated with this syndrome result in foreshortened digits with a partial cutaneous syndactyly between the index and middle digits.25,26

In Carpenter’s syndrome, the anomaly results from premature synostosis of the coronal suture, causing an acrocephalopolysyndactyly deformity. When unequal sutural closures are present, there is an asymmetric tower-shaped skull deformity. This craniosynostosis disorder is characterized again by the anomalies present, and there is a tendency to have congenital heart malformations.5,25,26

The clover-leaf skull, or Kleeblattschädel anomaly, results in a trilobed skull. This results from premature synostosis of varying combinations of the temporoparietal, coronal, lambdoidal, and metopic sutures. Hydrocephalus is associated with this deformity, in addition to a hypoplastic midface with exorbitism. There is a high mortality with this anomaly.

TABLE 3.7 Conditions with secondary craniosynostosis.

Metabolic disorders

Hyperthyroidism

Rickets (various forms)

Mucopolysaccharidoses and related disorders

Hurler’s syndrome

Morquio’s syndrome

Beta-glucuronidase deficiency

Mucolipidosis III

Hematologic disorders

Thalassemia

Sickle cell anemia

Polycythemia vera

Congenital hemolytic icterus

Malformations

Holoprosencephaly

Microcephaly

Encephalocele

Iatrogenic disorders

Hydrocephaly with shunt

Malformation secondary to shunt malfunction

3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification |

37 |

TABLE 3.8 Tessier classification.

A.Isolated cranial vault dysmorphism

B.Symmetric orbitocranial dysmorphism (with or without telorbitism)

1.Trigonocephaly

2.Acro-oxycephaly

3.Brachycephaly without telorbitism

4.Brachycephaly with euryprosopia and telorbitism

C.Asymmetric orbitocranial dysmorphism (plagiocephaly)

1.Pure vertical discrepancy of orbital cavities

2.Plagiocephaly without telorbitism

3.Plagiocephaly with telorbitism

D.Saethre-Chotzen syndrome group

E.Crouzon syndrome group

1.Regular Crouzon syndrome

2.Top Crouzon syndrome

3.Bottom Crouzon syndrome

4.Trilobular Crouzon syndrome

F.Apert’s syndrome group

1.Hyperacrocephalic Apert’s syndrome

2.Hyperbrachycephalic Apert’s syndrome

3.Pfeiffer syndrome

4.Trilobular Apert’s syndrome

5.Carpenter syndrome

The remainder of the anomalies classified and categorized by Tessier’s schema are extremely rare, and complex malformations and are not within the scope of this discussion.5,24,25

Summary

At present, no single classification satisfactorily explains all of the various craniofacial malformations, nor is one universally applicable to all specialties. The better known, more recent, and more widely accepted classifications have been briefly presented and discussed. Better classifications have evolved and are continuing to evolve through communication, standardization of terminology, and the advancement of the science of embryology and genetics. It still remains to develop an all-encompassing classification that will clarify the complex morphopathogenesis of craniofacial malformations.

References

1.Cohen MM Jr. Perspectives on craniosynostosis. West J Med. 1980;132:507.

2.Cohen MM Jr. Craniosynostosis and syndromes with craniosynostosis: incidence, genetics, penetrance, variability and new syndrome updating. Birth Defects. 1979;15:13.

3.Cohen MM Jr. An etiologic and nosologic overview of craniosynostosis syndromes. Birth Defects. 1975;11:137.

4.Cohen MM Jr., ed. Craniosynostosis—Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management. New York: Raven Press; 1986.

5.Dufresne C, Jelks G. Classification of craniofacial anomalies. In: Smith B, ed. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

Philadelphia: C.V. Mosby; 1987:1185–1207.

6.Dufresne C. Classifications of craniofacial anomalies. In:

Dufresne C, Carson B, Zinreich SJ, eds. Complex Craniofacial Problems. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1992:43–74.

7.DeMeyer W, Zemen W, Palmer CA. The face predicts the brain: diagnostic significance of median facial anomalies for holoprosencephaly (arrhinencephaly). Pediatrics. 1964;34:256.

8.DeMeyer W. Median facial malformations and their implications for brain malformations. Brain Defects. 1975;11:155.

9.Dufresne CR, Corner B, Richtsmeier J. Categorization of craniofacial dysmorphology for the prediction of surgical outcome. In: Montoya AG, ed. Craniofacial Surgery: Proceedings of the Fourth Meeting of the International Society of Cranio- Maxillo-Facial Surgery. Monduzzi, Italy: 1991:41–43.

10.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Levin SL, eds. Syndromes of the Head and Neck. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

11.Gorlin RJ, Cervanka J, Pruzansky S. Facial clefting and its syndromes. Birth Defects. 1971;7:3.

12.Harkins CS, Berlin A, Hardings RL, Longacre JJ, Snodgrass RM. A classification of cleft lip and cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1962;29:31.

13.Poswillo D. The pathogenesis of the first and second branchial arch syndrome. Oral Surg. 1973;35:302.

14.Kawamoto HK, David JD. Rare craniofacial clefts. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1990: 2922–2973.

15.Rogers BO. Rare craniofacial deformities. In: Converse JM, ed.

Reconstructive Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1964.

16.Sanvenero-Rosselli G. Developmental pathology of the face and the dysraphia syndromes—an essay of interpretation based on experimentally produced congenital defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1953;11:36.

17.Tessier P. Anatomic classification of facial, craniofacial and latero-facial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976;4:69.

18.Tessier P, Rougier J, Hervouet F, Woillez M, Lekieffre M, Derome P, eds. A new anatomical classification of facial clefts, craniofacial and laterolateral clefts and their distribution around the orbit. In: Plastic Surgery of the Orbit and Eyelids. New York: Masson; 1981:118–134.

19.Lund OE. Combination of ocular and cranial malformations with craniofacial dysplasia. Ophthalmologica. 1966;152:13.

20.Karfik V. Proposed classification of rare congenital cleft malformation in the face. Acta Chir Plast. 1966;8:163.

21.Moss ML. The pathogenesis of premature cranial synostosis in man. Acta Anat. 1959;37:351.

22.Poswillo D. Orofacial malformation. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67:13.

23.Tessier P. Orbital hypertelorism successive surgical attempts, material and methods causes and mechanisms. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;6:135.

24.Van der Meulen JC, Mazzola R, Vermey-Keers C, Sticker M, Raphael B. A morphogenetic classification of craniofacial malformations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:560.

25.Tessier P, Rougier J, Hervouet F, Woillez M, Lekieffre M, Derome P, eds. The craniofaciostenoses (CFS): the Crouzon and Apert diseases: the plagiocephalies. In: Plastic Surgery of the Orbit and Eyelids. New York: Masson; 1981:200–223.

26.Tessier P. Relationship of craniostenoses to craniofacial dysostoses and to faciostenoses. A study with therapeutic implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;48:224.

27.Moss ML. The primacy of functional matrices in orofacial growth. Dent Pract Rec. 1968;19:65.