- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Introduction

- •2. Evaluation of the Craniomaxillofacial Deformity Patient

- •3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification

- •4. Etiology of Skeletal Malocclusion

- •5. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Traumatic Defects

- •6. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Review of Nasal Deformities

- •7. Review of Benign Tumors of the Maxillofacial Region and Considerations for Bone Invasion

- •8. Oral Malignancies: Etiology, Distribution, and Basic Treatment Considerations

- •9. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Infections: Etiologies, Distributions, and Associated Defects

- •11. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Healing, Biomechanics, and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •12. Metal for Craniomaxillofacial Internal Fixation Implants and Its Physiological Implications

- •13. Bioresorbable Materials for Bone Fixation: Review of Biological Concepts and Mechanical Aspects

- •14. Advanced Bone Healing Concepts in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Bone Surgery

- •15. The ITI Dental Implant System

- •16. Localized Ridge Augmentation Using Guided Bone Regeneration in Deficient Implant Sites

- •17. The ITI Dental Implant System in Maxillofacial Applications

- •18. Maxillary Sinus Grafting and Osseointegration Surgery

- •19. Computerized Tomography and Its Use for Craniomaxillofacial Dental Implantology

- •20B. Atlas of Cases

- •21A. Prosthodontic Considerations in Dental Implant Restoration

- •21B. Overdenture Case Reports

- •22. AO/ASIF Mandibular Hardware

- •23. Aesthetic Considerations in Reconstructive and Corrective Craniomaxillofacial Bone Surgery

- •24. Considerations for Reconstruction of the Head and Neck Oncologic Patient

- •25. Autogenous Bone Grafts in Maxillofacial Reconstruction

- •26. Current Practice and Future Trends in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Microvascular Bone Surgery

- •27. Considerations in the Fixation of Bone Grafts for the Reconstruction of Mandibular Continuity Defects

- •28. Indications and Technical Considerations of Different Fibula Grafts

- •29. Soft Tissue Flaps for Coverage of Craniomaxillofacial Osseous Continuity Defects with or Without Bone Graft and Rigid Fixation

- •30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting

- •31. Microsurgical Reconstruction of Large Defects of the Maxilla, Midface, and Cranial Base

- •32. Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle

- •33. Problems Related to Mandibular Condylar Prosthesis

- •34. Reconstruction of Defects of the Mandibular Angle

- •35. Mandibular Body Reconstruction

- •36. Marginal Mandibulectomy

- •37. Reconstruction of Extensive Anterior Defects of the Mandible

- •38. Radiation Therapy and Considerations for Internal Fixation Devices

- •39. Management of Posttraumatic Osteomyelitis of the Mandible

- •40. Bilateral Maxillary Defects: THORP Plate Reconstruction with Removable Prosthesis

- •41. AO/ASIF Craniofacial Fixation System Hardware

- •43. Orbital Reconstruction

- •44. Nasal Reconstruction Using Bone Grafts and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •46. Orthognathic Examination

- •47. Considerations in Planning for Bimaxillary Surgery and the Implications of Rigid Internal Fixation

- •48. Reconstruction of Cleft Lip and Palate Osseous Defects and Deformities

- •49. Maxillary Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •50. Mandibular Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •51. Genioplasty Techniques and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •52. Long-Term Stability of Maxillary and Mandibular Osteotomies with Rigid Internal Fixation

- •53. Le Fort II and Le Fort III Osteotomies for Midface Reconstruction and Considerations for Internal Fixation

- •54. Craniofacial Deformities: Introduction and Principles of Management

- •55. The Effects of Plate and Screw Fixation on the Growing Craniofacial Skeleton

- •56. Calvarial Bone Graft Harvesting Techniques: Considerations for Their Use with Rigid Fixation Techniques in the Craniomaxillofacial Region

- •57. Crouzon Syndrome: Basic Dysmorphology and Staging of Reconstruction

- •58. Hemifacial Microsomia

- •59. Orbital Hypertelorism: Surgical Management

- •60. Surgical Correction of the Apert Craniofacial Deformities

- •Index

32

Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle

Joachim Prein

Indications for the application of an alloplastic prosthesis for the replacement of the mandibular condyle are extremely rare. Whenever possible, the reconstruction of the mandibular joint should be performed with autogenous material. Under certain conditions, however, it may be necessary to use a metal prosthesis. During the 20 years between 1974 and 1994, we treated 17 patients with 21 alloplastic prosthesis, mostly made out of steel. At the moment the use of an AO/ASIF alloplastic joint prosthesis is now permitted in the United States because they are FDA approved, currently as a 2.4 mm titanium locking reconstruction plate with condylar head right and left as 3 16, 4 18, and 5 20 hole sizes, and 2.4 mm titanium condylar plates 8 holes right and left (see Chapter 22).1–11

the condyle is replaced. In our patient group only partial arthroplasties were performed.

Patients

Between 1974 and 1994 17 patients received 21 prostheses. There were 10 females and 7 males. The mean age was 43.5 years (range 16 to 81). The first prosthesis ever used in our unit was placed in 1974 (surgery performed by Prof. Spiessl). This prosthesis in a young female is now in place for 23 years. The average duration of the 21 prosthesis until 1994 was 8.7 years (range, 13 to 244 months) (Figure 32.2).

Material

In the past, the system consisted of a prosthesis designed to replace the condyle without an artificial fossa. The prosthesis comes in three different sizes. The condylar part is shaped either like a sphere or a barrel. It is connected to a short prebent plate that can be fixed with four-to-six 2.7 screws at the ascending ramus. For those patients in whom part of the lateral mandible together with the joint was replaced, a prebent reconstruction plate with a condyle on top of the vertical part was used (Figure 32.1).

Tests have been made with titanum-coated prostheses and special adaptable condyles in combination with the THORP system. The adaptable version had joints in between the plate and condyle. The purpose was to facilitate the placement of the artificial condyle in the glenoid fossa. Because of technical problems, this version is no longer used.

Indications

In the majority of our patients (9 of 17) and the majority of all condyles replaced (12 of 21), the procedure was necessary because of an ankylosis. Most of these ankyloses were posttraumatic. One patient suffered from a Morbus Bechterew (spondylarthritis ankylopoetica) and had developed over a period of 18 years a bilateral ankylosis. Her range of motion at the time of surgery was 2 to 1 mm interincisal distance. She now says, 11 years after surgery, that she feels like a newborn person.

In 4 of 21 reconstructed joints, the indication was a tumor or metastasis. In these patients the lateral mandible together with the ascending ramus was replaced by a reconstruction plate with condylar head (Figure 32.3). Since 1994, we have immediately reconstructed the condylar area in severely comminuted fracture situations in several patients (Figure 32.4).

Method |

Operative Procedure |

Generally one distinguishes between a total and a partial arthroplasty. In a total arthroplasty the condyle is replaced together with an artificial fossa. In a partial arthroplasty only

In most of the operations, a two-site approach (preauricular and submandibular) was used. In ankylosis operations, the ankylotic mass was removed to create a thicker than normal

372

32. Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle |

373 |

FIGURE 32.1 The top three implants show different sizes of joint prostheses. The bottom three are prebent reconstruction plates with a solid barrel-like condylar head (2.7 system steel AO/ASIF).

a

b

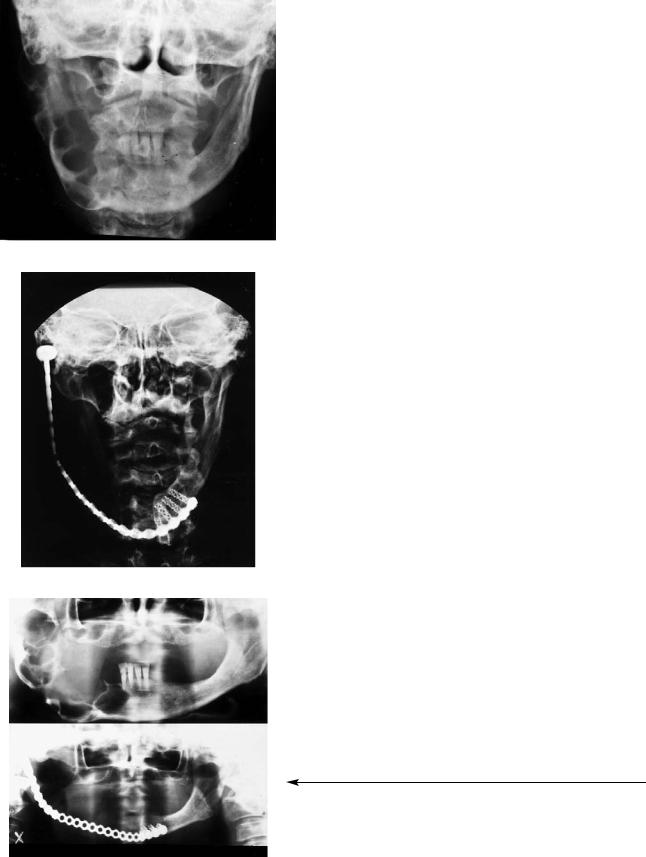

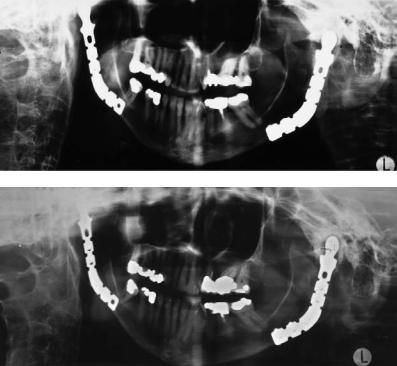

FIGURE 32.2 (a) Panoramic and (b) AP view of a patient with two condylar prostheses. Surgery was performed in 1988. The prostheses are still in place. The position is almost optimal, with satisfactory function.

374 |

J. Prein |

FIGURE 32.3 Indications for surgery for 21 joint replacements between 1974 and 1994.

pseudofossa to prevent the danger of a perforation of the artificial condyle through the base of the skull. An ipsilateral coronoidectomy was usually performed. In all other instances, whenever possible, the disc was left in place as a protection against perforation of the fossa. As a further measure against the danger of perforation we have always tried to place the prosthesis slightly inferior to the fossa. This, of course, is possible only if just for joint replacement. In those patients where

both the joint and the lateral mandible must be replaced, it is especially difficult to place the condyle correctly into the natural fossa and keep it there. However, we have seen postoperative displacements of the condyle into the temporal fossa without clinical consequences (Figure 32.5). Whenever possible, in all patients, intermaxillary fixation was applied during surgery to identify the optimal position for the prosthesis.

Results

Only in one patient with one prosthesis for an ankylosis in 1981 was the prosthesis removed 5 years later in another unit. The precise reasons are not known to us. Originally the patient suffered from an ankylosis with only 2- to 3-mm interincisal distance. One month after surgery his range of motion was 22 mm. He was very uncooperative and did not come back for postoperative control and exercises. As far as we could find out at the time of removal, the distance was 13 mm and no lateral or anterior motion was possible. Several further attempts under general anesthesia were undertaken to improve the range of motion after the removal of the prosthesis.

In general, lateral and anterior motions are almost impossible in patients with two prostheses. In those with one prosthesis, such motion is possible in a limited range.

FIGURE 32.4 Replacement of the left mandibular condyle after a comminuted fracture in this area and the mandibular body on the opposite side. The patient was a severe polytraumatized patient and is tetraplegic.

FIGURE 32.5 Replacement of the chin and right side of the mandible because of an osteosarcoma with a 2.7 reconstruction plate with condylar head. The condylar head is displaced laterally out of the fossa. The patient lives with good comfort, and the plate has been in place for over 3 years.

32. Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle |

375 |

|

a |

|

Occlusal problems have been observed, especially in se- |

|

vere trauma cases. In one patient, this problem developed be- |

|

|

cause regular treatment in due time with correct intermaxil- |

|

|

lar fixation was impossible as a result of the patient’s unstable |

|

|

general condition and paraplegia. Her accident occurred in |

|

|

1985, when immediate repair and stabilization of all facial |

|

|

fractures with plates was not yet a routine procedure. Her fa- |

|

|

cial structure would, without doubt, be much better today with |

|

|

the appropriate application of our treatment protocol for pan- |

|

|

facial fractures. |

|

|

|

Scars were problematic in only one young patient who de- |

|

veloped a broad hypertrophic scar. He had several interven- |

|

|

tions through his scar because of a laceration of his facial |

|

|

nerve (as a result of an accident) together with a severe frac- |

|

|

ture of his mandible. |

|

|

|

In most of our patients with ankylosis, considerable im- |

|

provement was achieved. Two patients with three prostheses |

|

b |

experienced occasional spontaneous locking with pain, which |

|

|

subsided after appropriate pain medication. In all patients, the |

|

|

range of motion with postoperative exercise was considerably |

|

|

improved. One patient felt some discomfort when it was very |

|

|

cold outside. In all instances, only rotational—and almost no |

|

|

gliding—movements were possible in the area of the artifi- |

|

|

cial joint. |

|

|

|

In all patients with wide resections because of tumor inva- |

|

sion and reconstruction with a long plate with a condyle, func- |

|

|

tion was better than in those patients with a condylar pros- |

|

|

thesis alone (Figure 32.6). This is remarkable, especially in |

|

|

view of the fact that placement of the artificial condyle in |

|

|

these instances is less accurate than for the patients with only |

|

|

the condylar prosthesis. |

|

Radiology

|

We observed no screw loosening. On PA views the position- |

|

|

ing of the prosthesis was correct in 50% of the cases. In 40% |

|

c |

of the patients, the artificial condyle was placed laterally and |

|

in 10% dislocation was observed. In 53% of the cases, appo- |

||

|

||

|

sitional bone deposition around the head of the prosthesis oc- |

|

|

curred. To a certain degree this leads to a limitation of mo- |

|

|

tion (Figure 32.7). |

|

|

In two patients with bilateral prostheses, bony resorption |

|

|

cranially from the condyle was seen without perforation of |

|

|

the middle cranial fossa. Only the two prostheses placed in |

|

d |

1974 and 1975 were positioned slightly too high. |

|

|

FIGURE 32.6 AP views (a) preoperatively and (b) postoperatively after resection of an extensive ameloblastoma. (c) Preoperative and (d) postoperative panoramic radiographs of the same patient. Surgery was done in 1984. The patient refused a bony reconstruction. The plate has been in place since 1984.

376 |

J. Prein |

a

b

In summary, indications for an artificial joint with an alloplastic prosthesis are rare. Although in all of our cases partial arthroplasties without fossa replacement were performed, perforation through the glenoid fossa was not observed. Periodic follow-up is necessary because a perforation in the area of the fossa can be asymptomatic. In our view, under certain conditions, the indication for an alloplastic prosthesis is given for ankylosed joints. Additional conditions are severely traumatized joints and patients with tumors invading the mandible or the soft tissues in the area of the joint. If possible, the patients must be well informed and able to be cooperative. Reconstruction with autogenous material, if the local and general conditions permit, is always preferable.

References

1.Kaban LB, Perrott DH, Fisher KA. Protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1145–1151.

2.Lindquist C, Söderholm A-L, Hallikainen D, et al. Erosion and heterotopic bone formation after alloplastic TMJ reconstruction.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:942–949.

3.Poswillo D. Experimental reconstruction of the mandibular joint. Int J Oral Surg. 1974;3:400–411.

FIGURE 32.7 Bilateral condylar replacement with steel prosthesis because of ankylosis: (a) 10 months postoperatively; (b) 3 years thereafter. Note: Anterior and posterior bony apposition around the artificial condyle.

4.Kent JN, Misiek DJ, Akin RK, et al. Temporomandibular joint condylar prosthesis: a ten year report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:245–254.

5.Kent JN, Block MS, Homsy CA, et al. Experience with a polymer glenoid fossa prosthesis for partial total temporomandibular joint reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44: 520–533.

6.Chassagne JF, Flot F, Stricker M, et al. A complete intermediate temporomandibular joint prosthesis. Evaluation after 6 years.

Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1990;91:423–429.

7.Raveh J, Stich F, Sutter F, et al. New concepts in the reconstruction of mandibular defects following tumor reconstruction.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:3–16.

8.Berarducci J, Thompson D, Scheffer R. Perforation into middle cranial fossa as a sequel to use of a proplast-Teflon implant for temporomandibular joint reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:496–498.

9.Chuong R, Piper M. Cerebrospinal fluid leak associated with proplast implant removal from the temporomandibular joint.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;74:422–425.

10.Estabrooks L, Fairbanks C, Collet R, Miller L. A retrospective evaluation of 301 TMJ proplast-Teflon implants. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:381–386.

11.Moricone E, Popowich L, Guernsey L. Alloplastic reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint. Dent Clin North Am. 1986;30:307–325.