- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Introduction

- •2. Evaluation of the Craniomaxillofacial Deformity Patient

- •3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification

- •4. Etiology of Skeletal Malocclusion

- •5. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Traumatic Defects

- •6. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Review of Nasal Deformities

- •7. Review of Benign Tumors of the Maxillofacial Region and Considerations for Bone Invasion

- •8. Oral Malignancies: Etiology, Distribution, and Basic Treatment Considerations

- •9. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Infections: Etiologies, Distributions, and Associated Defects

- •11. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Healing, Biomechanics, and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •12. Metal for Craniomaxillofacial Internal Fixation Implants and Its Physiological Implications

- •13. Bioresorbable Materials for Bone Fixation: Review of Biological Concepts and Mechanical Aspects

- •14. Advanced Bone Healing Concepts in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Bone Surgery

- •15. The ITI Dental Implant System

- •16. Localized Ridge Augmentation Using Guided Bone Regeneration in Deficient Implant Sites

- •17. The ITI Dental Implant System in Maxillofacial Applications

- •18. Maxillary Sinus Grafting and Osseointegration Surgery

- •19. Computerized Tomography and Its Use for Craniomaxillofacial Dental Implantology

- •20B. Atlas of Cases

- •21A. Prosthodontic Considerations in Dental Implant Restoration

- •21B. Overdenture Case Reports

- •22. AO/ASIF Mandibular Hardware

- •23. Aesthetic Considerations in Reconstructive and Corrective Craniomaxillofacial Bone Surgery

- •24. Considerations for Reconstruction of the Head and Neck Oncologic Patient

- •25. Autogenous Bone Grafts in Maxillofacial Reconstruction

- •26. Current Practice and Future Trends in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Microvascular Bone Surgery

- •27. Considerations in the Fixation of Bone Grafts for the Reconstruction of Mandibular Continuity Defects

- •28. Indications and Technical Considerations of Different Fibula Grafts

- •29. Soft Tissue Flaps for Coverage of Craniomaxillofacial Osseous Continuity Defects with or Without Bone Graft and Rigid Fixation

- •30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting

- •31. Microsurgical Reconstruction of Large Defects of the Maxilla, Midface, and Cranial Base

- •32. Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle

- •33. Problems Related to Mandibular Condylar Prosthesis

- •34. Reconstruction of Defects of the Mandibular Angle

- •35. Mandibular Body Reconstruction

- •36. Marginal Mandibulectomy

- •37. Reconstruction of Extensive Anterior Defects of the Mandible

- •38. Radiation Therapy and Considerations for Internal Fixation Devices

- •39. Management of Posttraumatic Osteomyelitis of the Mandible

- •40. Bilateral Maxillary Defects: THORP Plate Reconstruction with Removable Prosthesis

- •41. AO/ASIF Craniofacial Fixation System Hardware

- •43. Orbital Reconstruction

- •44. Nasal Reconstruction Using Bone Grafts and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •46. Orthognathic Examination

- •47. Considerations in Planning for Bimaxillary Surgery and the Implications of Rigid Internal Fixation

- •48. Reconstruction of Cleft Lip and Palate Osseous Defects and Deformities

- •49. Maxillary Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •50. Mandibular Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •51. Genioplasty Techniques and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •52. Long-Term Stability of Maxillary and Mandibular Osteotomies with Rigid Internal Fixation

- •53. Le Fort II and Le Fort III Osteotomies for Midface Reconstruction and Considerations for Internal Fixation

- •54. Craniofacial Deformities: Introduction and Principles of Management

- •55. The Effects of Plate and Screw Fixation on the Growing Craniofacial Skeleton

- •56. Calvarial Bone Graft Harvesting Techniques: Considerations for Their Use with Rigid Fixation Techniques in the Craniomaxillofacial Region

- •57. Crouzon Syndrome: Basic Dysmorphology and Staging of Reconstruction

- •58. Hemifacial Microsomia

- •59. Orbital Hypertelorism: Surgical Management

- •60. Surgical Correction of the Apert Craniofacial Deformities

- •Index

6

Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Review of Nasal Deformities

John G. Hunter

The nose is the central feature of the human face, both anatomically and aesthetically. The normal, natural nose is made up of thin mucosal lining, sculptured alar cartilages, bone and cartilage struts that buttress the dorsum and side walls, and a conforming canopy of thin skin which compliments the face in color and texture.1

The nose is a pyramidal structure; its apex projects anteriorly, and its base attaches to the facial skeleton. The nasal pyramid consists of four parts: the bony pyramid, consisting of the paired nasal bones and projecting frontal processes of the maxillae; the cartilaginous vault, consisting of the paired upper lateral cartilages, which are attached to the deep surface of the more cephalic nasal bones; the lobule, consisting of the nasal tip, paired lower lateral alar cartilages, alae, vestibular regions, and columella; and the nasal septum. The alar cartilages articulate with the caudal edge of the upper lateral cartilages and the supporting septum. The nasal septum consists of the quadrilateral cartilage, perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, and the vomer, with minor contributions from the maxilla and palatine bone.2

In addition to its obvious aesthetic significance, the functional importance of the nose cannot be overemphasized. The nose plays major roles in humidification, warming and filtration of inspired air, immune function, and olfaction. Disruption of these nasal functions adversely affects an individual’s sense of well-being and quality of life, as well as having significant health implications.3

Deformities of nasal structures are legion, ranging from subtle contour irregularities to devastating malformations or complete absence. Nasal deformities have been described as resulting from the following, among others: intrauterine and maternal (extrauterine) exposures; as components of hereditary conditions and craniofacial clefts; congenital cysts and encephaloceles; trauma in the prenatal, natal, and postnatal periods; tumors and tumor ablation; infections; and iatrogenic causes.

Regardless of etiology, significant nasal deformities can have lifelong consequences for those afflicted. They repre-

sent a formidable challenge for the surgeon seeking to restore nasal form, function, or both. In this chapter, the more common congenital, developmental, and acquired nasal deformities, particularly those involving the nasal bones, will be reviewed.

Congenital Nasal Deformities

Embryology

Congenital malformations of the nose are rare, with posterior choanal atresia probably occurring most frequently.4 Although teratogenic influences may occur anytime up to birth, the sixth to eighth weeks and the fourth month of gestation are critical. Nasal anomalies arise as primary embryologic defects or as secondary to defects in other facial units, such as cleft lip and palate.5

An understanding of the normal events in the embryologic development of the face and nose facilitates understanding congenital nasal deformities, especially cleft lip and palate nasal deformities and the rare craniofacial clefts. The embryologic development of the face takes place between the fourth and eighth weeks of gestation. The midportion of the face develops immediately anterior to the forebrain by differentiation of the frontonasal prominence. The ectodermal nasal placodes arise from either side of the frontonasal prominence cephalic to the stomodeum. Elevation of mesoderm at the placode margins produces a horseshoe-shaped ridge, which opens inferiorly. The median and lateral nasal processes are formed from the placode limbs.6

The paired median nasal processes merge with the frontonasal prominence to form the frontal process. As the structures enlarge, the frontonasal process is displaced in a cephalic direction. The median nasal processes coalesce in the midline in the sixth week, while their caudal segments, the globular processes, coalesce as they expand above the midportion of the stomodeum. The premaxilla, philtrum, columella, nasal

49

50

tip, cartilaginous septum, and primary palate arise from the paired median elements. The more cephalic frontonasal processes narrow to form the nasal dorsum and radix, while the lateral nasal processes form the nasal alae.6

In Utero Exposures

Either intrauterine or extrauterine disease may cause nasal developmental deformities. Exposure to maternal medications and illnesses during the sixth, seventh, and eighth weeks of embryologic development may result in deformities of olfactory and nasal structures.7

Extrauterine diseases, such as measles, chicken pox, and syphilis, are known to cause defective nasal development. Maternal medications may also affect the developing fetus. Exposure to hydantoin in this critical period may result in fetal hydantoin syndrome. Its features include midface hypoplasia and depression of the nasal dorsum, as well as heart defects, growth and mental retardation, cleft lip or palate, and epicanthal folds. Between 5% and 10% of children of mothers with seizure disorders taking hydantoin during early pregnancy develop the full syndrome.8

Another maternal medication implicated in defective nasal development is warfarin, an oral anticoagulant. Although it is well known that warfarin use in late pregnancy may result in fetal or placental hemorrhage, potential teratogenic effects of the drug were unappreciated until 1966, when the congenital warfarin syndrome was first described. This syndrome includes nasal bone deformities, stippling of bone, optic atrophy and mental retardation. Hypoplasia of the nasal bones is the most common anomaly reported. The nose is flat, the nasal septum is short, and a deep groove between the ala and nasal tip is sometimes present. The nasal abnormality usually results in breathing and feeding difficulties. The exact mechanism of warfarin teratogensis is uncertain. As low-molecular- weight warfarin can cross the placenta, the bone deformities are believed to be due to microhemorrhage into fetal cartilages, which subsequently heal by calcification, giving the bones a stippled appearance on x-ray.4

Nasal obstruction has also been reported in newborn children of mothers taking reserpine during the first trimester. In these cases, the cartilaginous nasal capsule, beginning about the third month, gradually becomes replaced by bone.7

Intrauterine exposure to ethanol in the first trimester of pregnancy may also result in fetal alcohol syndrome, a mild form of holoprosencephaly. It is characterized by a narrow forehead, short palpebral fissures, a small short nose and midface, and a long upper lip with deficient philtrum.9

Chromosome Disorders: Nasal Manifestations

J.G. Hunter

translocations, and deletions. Nasal defects are seen in many chromosome disorders.

Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) is a fairly common chromosome disorder with an increasing risk of occurrence with advancing maternal age (1 in 50 at age 45). Multiple craniofacial anomalies are present, including a small nose with flat dorsum. Nasal deformities are also seen in the following chromosome disorders: Trisomy 13 (broad, flat nasal dorsum); 9p trisomy (bulbous nose); 4p syndrome (broad nasal tip); XXXY syndrome (saddle nose deformity).8

Nasal Deformities in Hereditary Conditions

Cleft Lip Nasal Deformity

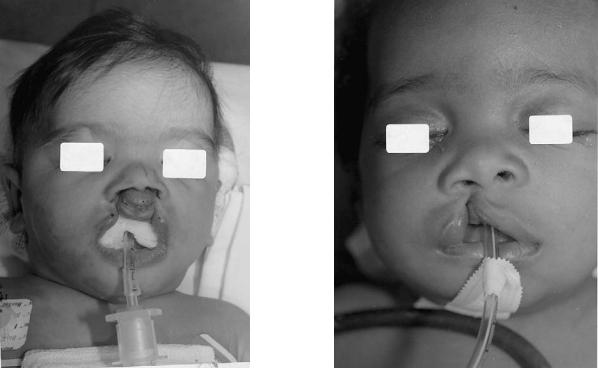

One of the most common congenital anomalies of the nose is that seen in association with cleft lip deformities. Some degree of nasal deformity is present in all cleft lip patients, even those with incomplete clefts (Figure 6.1). While the cleft lip nasal deformity is usually characteristic, its severity varies with each case and is directly related to the extent of the lip deformity. In bilateral clefts, a double-sided nasal deformity occurs, reflecting the degree of anomaly present on each side (Figure 6.2).5,10

Components of the nasal deformity include defects of the alar cartilage on the cleft side, the septum, columella, and nasal tip, and the entire nasal pyramid. Maxillary clefting and hypoplasia and malpositioning of maxillary segments contribute significantly to nasal asymmetry. Anatomic and functional deformities of the orbicularis oris muscle also contribute to the nasal deformity.10

The etiology of the cleft lip nasal deformity is debated. An intrinsic defect or deficiency of growth of the medial and lat-

Chromosome disorders can result from abnormalities of chro-

mosome number, sex chromosome type or number, or indi- FIGURE 6.1 Unilateral incomplete cleft lip. Note characteristic nasal vidual chromosome rearrangements such as inversions, deformity.

6. Review of Nasal Deformities

FIGURE 6.2 Bilateral cleft lip with bilateral nasal deformity.

eral nasal processes, with an absence of mesodermal penetration of the soft tissues in the cleft region, has been postulated. Multifactorial inheritance and environmental influences have been demonstrated. The degree of severity of the deformity is related to the embryologic period in which the disturbance occurs.10

Cleft lip nasal deformities result from tissue deficiency of the cleft lip, a deficiency of the maxilla, or abnormal pull on the nasal structures. The role of tissue deficiencies extrinsic to the nose has been emphasized.10

The nasal deformity of a unilateral cleft lip is characterized by the following (Figure 6.3):

1.Deviation of the caudal septum and nasal spine to the cleft side by the unrestricted muscle pull of the normal side

2.Displacement of the alar base laterally and inferiorly by unopposed muscle forces, with retrodisplacement owing to maxillary hypoplasia on the cleft side

3.The nasal dome is lower on the cleft side and the ala flattened, with inward buckling. Increased nostril circumference results

4.The medial crus of the alar cartilage is displaced, and the columella shorter, on the cleft side. The columella is obliquely oriented, with its dorsal end slanted toward the noncleft side

5.The nasal floor is absent in complete clefts

51

FIGURE 6.3 The nasal deformity associated with a unilateral cleft lip.

6.The nasal bone on the cleft side is affected by growth and muscle pull. Unrestricted noncleft side pull deviates the cleft side nasal bone medially and vertically

The deformity of a bilateral cleft simply duplicates these deformities, adds the effects of an unstable premaxilla, and accentuates the lack of definitive columellar and philtral columns (Figure 6.2).5

Maxillonasal Dysplasia (Binder’s Syndrome)

Maxillonasal dysplasia, or Binder’s syndrome, is a distinct malformation characterized by a flattened nasal profile on a retruded base. The syndrome’s etiology, although unknown, has been postulated to be either a congenital malformation or to occur secondary to midface trauma. A hereditary association has been reported but remains undefined. Prior to its description in 1962, the anomaly had not been clearly differentiated from other forms of midface hypoplasia, such as Crouzon and Apert syndromes, and posttraumatic nasomaxillary retrusion.11,12

The syndrome results in hypoplasia of the maxilla and nose, while sparing the malar region. The flattened nasal profile is characteristic. Associated with the nasomaxillary deformity is an excessively obtuse or absent nasofrontal angle, shortened columella, flattened alae, and class III malocclusion. The

52

skeletal deformity causing the anomaly is typically a palpable depression in the anterior nasal floor and localized maxillary hypoplasia in the alar base region.11,12

Craniofacial Synostoses Syndromes

Craniosynostosis denotes premature fusion of one or more sutures in either the cranial vault or base. Most clinical observations are isolated suture synostoses that occur in a sporadic fashion. There are rare, inherited, distinct craniofacial synostosis syndromes that share common features, such as midface hypoplasia and facial and limb deformities, along with suture synostoses. Among the more common anomalies, such as Apert, Crouzon, and Pfeiffer syndromes, nasal deformities are commonly seen. Inheritance is usually autosomal dominant.13

The nasal deformities usually seen are hooked, flat nose (Crouzon, Apert) and flat nasal dorsum (Pfeiffer, SaethreChotzen syndromes). The nasal deformities are seen in association with, and probably secondary to, maxillary hypoplasia.8

Holoprosencephaly

Holoprosencephaly refers to a group of anomalies resulting from partial or complete failure of the anterior neural tube to form cerebral hemispheres with ventricles, so that there is only one forebrain cavity in severe cases.9

Holoprosencephaly is characterized by a wide range of facial anomalies, ranging from premaxillary agenesis through cebocephaly to cyclopia and ethmocephaly. The defects result from well-defined loss of midline tissues in the face, secondary to midline deficiency of the anterior neural plate, leading to small medial nasal prominences. Inheritance is mostly sporadic, but chromosome abnormalities should be excluded. Maternal exposure to ethanol has been demonstrated to be causative. Indeed, one of the mildest forms of holoprosencephaly is fetal alcohol syndrome.

Nasal deformities, as expected, run the gamut from complete absence (arrhinia), proboscis deformity, or cebocephaly (single nostril) in severe cases to the small, short nose seen in fetal alcohol syndrome.8,9

Frontonasal Dysplasia

Another rare anomaly with distinct nasal deformities is frontonasal dysplasia. Central features include hypertelorism, bifid nasal tip, or complete midline splitting of the nose. Other features seen include median cleft palate and anterior encephalocele. Inheritance is usually sporadic.8

Achondroplasia

Achondroplasia is a bone dysplasia characterized by short stature, large head with prominent forehead, midface hy-

J.G. Hunter

poplasia, lumbar lordosis, and extremity deformities. A saddle nose deformity with short, flat nasal bones is present in most cases. Inheritance is autosomal dominant, but 70% to 80% of cases are new mutations.8

Miscellaneous

Numerous dysmorphic syndromes have nasal deformities as minor features. These conditions and the nasal anomaly present include the following: Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (prominent hook nose with broad dorsum); multiple pterygium syndrome (saddle nose deformity); cerebro-ocular- facio-skeletal syndrome (COFS) (prominent nasal dorsum); Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (flat dorsum); tricho- rhino-phalangeal syndrome (bulbous dorsum); and MardenWalker syndrome (flat dorsum).8

Rare Craniofacial Clefts

Craniofacial clefts exist in a multitude of patterns and degrees of severity. Although they often appear initially bizarre, most craniofacial clefts occur along predictable embryologic lines. Their exact incidence is unknown, and estimates of their occurrence vary widely. Bilateral involvement may occur. Among the rare craniofacial clefts, nasal involvement is relatively common.6

Two theories are most commonly postulated for facial cleft formation—failure of fusion of the facial processes or failure of mesodermal migration and penetration. Any mishap interfering with normal craniofacial embryologic development, occurring between the fourth and eighth week of gestation, may lead to cleft formation.6

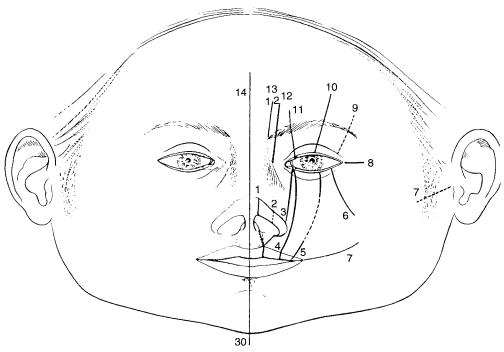

Although a number of classification systems for craniofacial clefts exist, the Tessier classification14 (Figure 6.4) is most widely employed today and will be used here. The following rare craniofacial clefts involve the nose:

No. 0 cleft (median craniofacial dysrhaphia). Midline cleft of the face. The cleft goes through the midline of the nose, with nasal septal thickening or duplication, and through the columella, maxilla, and upper lip. The nose is often bifid, with broad flattened nasal bones. Arrhinia or a proboscis deformity may occur. The No. 0 cleft includes most midline deformities described in other classification systems, including frontonasal dysplasia and holoprosencephaly. Cephalic continuation of the cleft, with cranial involvement, is the No. 14 cleft.

No. 1 cleft (paramedian craniofacial cleft). The No. 1 cleft passes through the dome of the alar cartilage with notching of the dome region of the nostril. The skeletal component of the cleft passes between the nasal bone and the frontal process of the maxilla. Although the septum is spared, the nasal bone on the involved side may be absent.

No. 2 cleft. The No. 2 cleft may be a transition between the No. 1 and No. 3 clefts. The cleft is slightly more lateral

6. Review of Nasal Deformities |

53 |

FIGURE 6.4 Tessier classification of facial and cranial clefts. Cleft localization on the soft tissues. (From Tessier, by permission of J Maxillofac Surg. 1976;4:69–92)

than the No. 1 cleft. The lateral aspect of the nose is flattened and the nasal bridge is broad.

No. 3 cleft (oculonasal cleft). The No. 3 cleft is a medial orbitomaxillary cleft extending through the lacrimal portion of the lower eyelid. The cleft undermines the base of the nasal ala. Hypoplasia of the lateral aspect of the nose is evident.14

Nasal Gliomas and Encephaloceles

Nasal gliomas and encephaloceles are rarely lesions with similar appearance and embryogenesis. Gliomas are deposits of cranial tissue in an extradural site, which have not maintained an attachment to the central nervous system. Approximately 15% of gliomas have a fibrous connection to the subarachnoid space. Encephaloceles maintain a connection to the central nervous system but are histologically identical to gliomas.5

An encephalocele is a protrusion of part of the cranial contents through a defect in the skull. The mass may contain meninges (meningocele), meninges and brain (meningoencephalocele), or meninges, brain and part of the ventricular system (meningoencephalocystocele).15

Nasal Encephalocele

foramen cecum. It has been suggested that in the development of nasal encephaloceles the cranial content protrusion exits first, with subsequent bone formation around it.15

The bony defects associated with frontal and nasal encephaloceles have been included in many craniofacial classification systems. Frontonasal encephaloceles may be classified as Tessier No. 14 clefts.14

Nasal encephaloceles are classified into three groups according to the site of facial protrusion: nasofrontal, nasoethmoidal, or nasoorbital:

Nasofrontal type. The protrusion passes through a defect in the frontoethmoidal junction and passes directly forward between the frontal and nasal bones.

Nasoethmoidal type. The protrusion is lower and passes through a defect in the frontoethmoidal junction, emerging between the nasal bones and the upper lateral cartilages. Variations of this defect include nasal gliomas and midline nasal cysts and sinuses.

Nasoorbital type. The protrusion passes from the frontoethmoidal junction down behind the nasal bones, then extending laterally through a defect between the lacrimal bone and the frontal process of the maxilla. The lesion presents as a protrusion in the soft tissue between the nose and the lower eyelid.15,16

The site of the defect in nasal encephalocele development is between the frontal and ethmoid bones, corresponding to the

Lower nasofrontal and nasoethmoidal encephaloceles increase the distance between the frontal and nasal bones or be-

54

tween the nasal bones and the nasal cartilages, giving rise to a long-appearing nose. Furthermore, by displacing the medial orbital wall laterally, telecanthus or true hypertelorism may occur. Other clinical features include either soft tissue swelling in response to the protrusion or a wrinkled area due to collapse of the encephalocele.15

The prognosis for patients with nasal encephaloceles is excellent. Any brain tissue involved is from the frontal lobe and its sacrifice is not associated with significant neurological deficits.15,16

Nasal Gliomas

Most nasal gliomas are noticed at birth or in early childhood. They may be extranasal (60%), intranasal (30%), or combined intranasal and extranasal (10%). Extranasal gliomas are smooth, firm compressible masses that usually occur along the nasomaxillary suture or glabella. They occasionally occur in the nasal midline. Unlike encephaloceles, extranasal gliomas rarely cause bony defects. Intranasal gliomas may result in nasal airway obstruction or septal deviation. They appear as firm, noncompressible polypoid masses within the nasal cavity. Widening of the nasal bony pyramid and hypertelorism are possible with large gliomas.5

Nasal Dermoids

Nasal dermoids are congenital ectodermal cysts seen at or shortly after birth. They comprise between 1% and 2.5% of all dermoids. Being uncommon, diagnosis is often delayed. The time lag to diagnosis allows growth and increases the probability of infection, thereby complicating definitive removal.17

Nasal dermoid cysts contain skin appendages—hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands. They represent areas of embryonal epithelium that survive along nasal bone fusion lines. A true dermoid cyst may occur subcutaneously on the nasal dorsum superficial to the nasal bones without a cutaneous opening. They therefore appear as slowly enlarging masses that may gradually deform the underlying nasal skeleton. However, a dermoid sinus, with or without a cyst, is an extensive lesion extending into nasal cartilage and bone. The dermoid cyst with sinus is usually visible at birth, and its punctum is usually located at the nasal osteocartilaginous junction. Discharge of casseous material and the presence of a hair tuft are diagnostic. Deep extension of the sinus tract occurs in 45% of cases. It may be predicted when nasal bone splaying or hypertelorism are present.5,7

Although very uncommon, intracranial extension of nasal dermoids through the cribiform plate may occur. Nasal dermoids may result in significant deformities, including dorsal saddling, open-roof deformity, and extensive scarring.17

J.G. Hunter

Nasal Injuries

Nasal Trauma in the Prenatal and Natal Periods

Injuries to the nose, secondary to pressure effects, occur more often than is commonly appreciated during pregnancy and parturition.7,18 Dislocation of the nasal septum may influence both the quantitative and qualitative development of maxillary, premaxillary, and nasal structures. Facial asymmetries and dental malocclusions may result.7

Persistent in utero pressure may result in fetal compression effects. Fetal compression may cause a number of deformities, including nasal-tip depression, saddle-nose deformity, micrognathia, craniostenosis, cleft deformities, and positional deformities of the limbs. Maternal uterus malformations are a common association.8

Owing to its prominent location, the nose is at particular risk to injury during the birth process. Of vaginally delivered white babies, about 7% have marked nasal deformities and 30% to 50% have temporary nasal flattening at birth. The temporary flattening results from dislocation of the septum during parturition; the degree of compression and resulting flattening is a function of the relationship between fetal head size and maternal pelvis size.7

Two basic types of septal deformity are seen in the newborn: anterior nasal deformity and combined septal deformity. These deformities may occur independently or together. They are considered to be acquired from different types of pressure on the fetus during pregnancy or parturition18:

The anterior nasal deformity is due to direct trauma and occurs in approximately 4% of normal vaginal deliveries. It is rarely seen following cesarean section. It is usually associated with asymmetry of the external nares, bending of the anterior septal cartilage, and distortion of the bony nasal pyramid and the septal cartilage-nasal spine junction. Minor deformity and cartilage bending is usually self-reduc- ing. If the deformity persists beyond three days, however, deformity of the nasal bones is also present.

The combined septal deformity is a true facial deformity, caused by compression of the maxilla. The result is malocclusion, elevation of the palatal arch, and compression of the septum against the base of the skull. The orientation of the distorting pressure forces determines the type and degree of deformity seen. Manipulation is required to expand the maxilla and straighten and realign the septum. Indications for manipulation are stuffy nose, respiratory problems and cyanotic attacks, feeding problems, and sticky, infected eyes.18

Nasal Injuries in Childhood

As the most exposed and prominent feature of the face, the nose naturally bears the brunt of many injuring forces. It is,

6. Review of Nasal Deformities

in fact, the most frequently injured facial structure.19 Nasal injuries in childhood are often so seemingly trivial that neither the mother nor the child remembers when they occurred. Apparently mild injuries may result in a poorly functioning nose, a major aesthetic deformity later in life, or both. Early injuries are frequently difficult to diagnose. They may influence developmental patterns that affect function as the child matures. External nasal deformities seen in adulthood may result from a combination of apparently minor childhood injuries and growth factors.7 The adverse consequences of nasal injuries during childhood is also reflected by the observation in a large series reviewing septal deformities present at birth that the incidence of straight septa was 42%, while in adult surveys, only approximately 20% are straight.18

Nasal injuries in childhood, as noted earlier, frequently have a profound effect on subsequent nasomaxillary growth and development, even after accurate diagnosis and proper treatment. Any child presenting with a nasal injury must also be evaluated for the presence of a septal hematoma. A septal hematoma presents as a bulging collection between the septal cartilage and overlying mucoperichondrium, and it may obstruct the nasal airway. If it is not promptly evacuated, pressure necrosis of the septal cartilage, with possible subsequent collapse of the nasal dorsum, may occur, resulting in saddle nose deformity.20

Septal abscess is an uncommon but serious cause of nasal deformities in children. Septal abscesses are usually the result of untreated or inadequately treated septal hematomas, which subsequently become infected. Marked nasoseptal destruction involving both the cartilaginous septum and the upper lateral cartilages may result.7

When cartilage is destroyed by hematoma or abscess, it is replaced by fibrous tissue. Scar retraction and loss of support of the lower two-thirds of the nose results in saddling of the dorsum, retraction of the columella, and widening of the alar base. Traumatic loss of the cartilaginous septum in early childhood may also cause maxillary hypoplasia. Injuries to the septum may also lead to buckling and twisting or cartilaginous hypertrophy with resultant nasal airway obstruction.

Facial fractures in adults, especially those of the midface, tend to be fragmented, whereas incomplete fractures predominate in childhood. Only 1% of facial fractures occur before age six; 5% occur prior to age 12. The frequency, distribution, and pattern of facial bone fractures begin to mirror those observed in adulthood by early adolescence. In most large series, fractures of the nasal bones and mandible account for the majority of pediatric maxillofacial fractures.20 Although bony injuries are frequently discussed, injuries to the cartilaginous portions of the nose occur much more frequently than fractures in children, and, as stated earlier, may have a profound effect on subsequent development.

Nasal dorsum hematomas occur less frequently than septal hematomas, but if inadequately treated, they may result in significant nasal deformity. They usually result from direct blunt trauma to the dorsum with avulsion of the upper

55

lateral cartilages from the nasal bones. Subsequent dissecting bleeding occurs. Pressure necrosis of the underlying nasal bone and/or upper lateral cartilage can result in depression or saddling.7

Nasal Injuries in Adolescence and Adulthood

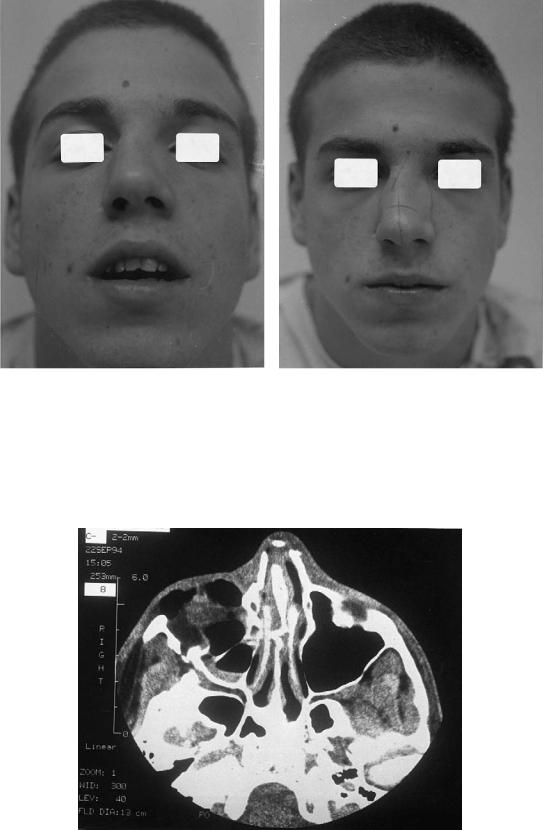

Nasal fractures are said to account for 39% of all facial fractures. One extensive survey demonstrated an annual incidence of 53.2 per 100,000 population.21,22 Although considered a relatively unimportant injury, optimal treatment of nasal fractures is needed to prevent long-term cosmetic and functional deformities (Figure 6.5).21

Blunt trauma caused by assault or fighting, motor vehicle accidents, and sports injuries is the most common cause of nasal fractures in adults.19 Lateral fractures (Figures 6.6a,b) (66%), linear fractures (20%), and frontal fractures (13%) are most commonly observed. Septal fractures occur approximately 14% of the time, always in association with a fracture of the external nose (Figure 6.7).22

Closed reduction of depressed or deviated nasal fractures is the norm, with no manipulation required for linear fractures. Long-term follow-up following fracture reduction, compared with a noninjured control group, revealed that secondary deformities—saddling or dorsal hump formation— occurred infrequently and that most deformities seen were of little consequence.21

Nasal Tumors

Primary tumors of the skin—basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma—are fairly frequent causes of nasal deformity, either as a result of direct invasion of underlying nasal structures or as a consequence of tumor

FIGURE 6.5 Cosmetic and functional deformity resulting from untreated nasal fracture. Note deviation of the nasal lobule to the left, with displacement of the caudal cartilaginous septum.

56 |

J.G. Hunter |

a |

b |

FIGURE 6.6 (a,b) Visible nasal deformity after lateral fracture. Note deviation of the nasal pyramid to the right following blunt trauma.

FIGURE 6.7 CT scan. Blunt injury with frontal nasal fracture and septal fracture with buckling.

6. Review of Nasal Deformities

ablation. Tumor invasion or surgical resection of the various nasal subunits up to total nasal amputation may be seen.23 Primary nasal tumors, however, are quite rare, with an annual incidence of less than 1 per 100,000 population in the United States. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of the nose. Squamous cell carcinoma can originate from the vestibule, lateral nasal wall, turbinates, meatus, or septum. Adenocarcinoma, chondrosarcoma, primary nasal malignant melanoma, and hemangiopericytoma are very rare nasal malignancies.24 As with the more common overlying skin tumors, primary nasal malignancies and their ablation

may result in significant nasoseptal deformity.

Benign tumors of the nose are even rarer than malignant lesions. In decreasing order of frequency, the more common benign nasal tumors are osteoma, hemangioma, papilloma, and angiofibroma.24

Nasal bone hemangiomas may be bony or mixed bony and soft tissue. They present as slowly enlarging masses at the nasal radix. Destruction of the involved nasal bone may occur, and ablation requires nasal bone resection.25

Nasal Deformities Resulting from Systemic Disease

Autoimmune disorders and infectious agents are often overlooked and poorly understood causes of nasal deformity and tissue destruction. Systemic diseases with nasal manifestations are often insidious in their early presentation, frequently resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. Systemic diseases with nasal manifestations are characterized as follows: autoimmune and connective tissue, lymphoma-like, granulomatous, and infectious.26

Systemic diseases with potentially deforming nasoseptal manifestations include:

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a systemic vasculitis with preferential involvement of the respiratory tract. The disease usually beginning with limited organ involvement progressing to a disseminated vasculitis with upper airway, lung, and kidney manifestations. Wegener’s granulomatosis may result in diffuse nasal mucosal ulceration, septal perforation, and nasal dorsal defects or collapse.

Relapsing polychondritis is an autoimmune connective tissue disorder characterized by intermittent cartilage inflammation, causing chondrolysis and atrophy. Cell-mediated immunity to cartilage has been demonstrated in vitro. Nasal cartilage involvement results in eventual collapse and saddle nose deformity.

Polymorphic reticulosis (T-cell lymphoma), formally known as lethal midline granuloma, and idiopathic midline destructive disease (IMDD) are lymphoma-like diseases that may manifest as destructive lesions or ulcerations causing nasal deformity. IMDD is a diagnosis of exclusion in patients who

57

manifest midline nasal necrosis with no specific etiology such as infection, tumor, or Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Fungal and atypical bacterial opportunistic infections may result in destructive lesions of the nose and septum. Potentially deforming infections include rhinoscleroma, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, rhinosporidiosis, and mucormycosis.26

Nasal Deformities Resulting from Cocaine Abuse

The destructive effects of cocaine on the nasal cavity and septum are well known to otolaryngologists and plastic surgeons. Epistaxis and nasal congestion frequently occur in the occasional intranasal cocaine abuser. Other common findings include excessive “sniffing,” sinusitis, diminished olfaction, and crusting. A severe form of rhinitis medicamentosa may accompany cocaine use, progressing to chronic injury of the nasal mucosa and perichondrium. Ultimately, ischemic necrosis of the septum and subsequent perforation may result.27,28

More serious nasal findings related to cocaine insufflation include osteocartilaginous necrosis, alar necrosis, and saddle deformity. The deleterious effects seen are due to both the profound vasoconstriction and local ischemia, leading to reperfusion injury, caused by topical cocaine, as well as chemical irritation by adulterants present in the drug itself.27,28

Recently, midline nasal destruction secondary to cocaine abuse, mimicking IMDD but less fulminant in its course, has been described.27

Iatrogenic Nasal Deformities

Aesthetic rhinoplasty and functional septorhinoplasty are undoubtedly the most common causes of significant iatrogenic nasal deformities. In the best of hands, secondary surgery of the nose is necessary in approximately 5% to 10% of rhinoplasty patients. Usually, the secondary procedure required is minor and involves further nasal reduction, such as rasping a small residual hump or correcting a persistent septal deviation.29

Overresection of the nasal osteochondrous skeleton during primary rhinoplasty results in more significant nasal deformities, including the supratip deformity, wide nasolabial angle, low radix, and inverted V deformity.30 Saddle nose deformity may result from combining radical submucous resection (Killian) of the cartilaginous septum, along with either resection of a large dorsal hump or, more commonly, overzealous lowering of the dorsum.29

Orthognathic and craniofacial surgery may also result in iatrogenic nasal deformities. Standard hypertelorism operations have been demonstrated to interfere with subsequent anterior facial growth and have been complicated by gradual resorption of the reconstructed complex.31

58

References

1.Burget GC, Menick FJ. Nasal support and lining: the marriage of beauty and blood supply. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:189– 203.

2.Graney DO, Baker SR. Anatomy. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LE, et al., eds. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1993:627– 639.

3.Leopold DA. Physiology of olfaction. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LE, et al., eds. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1993:640–664.

4.Zakzouk MS. The congenital warfarin syndrome. J Laryngol Otol. 1986;100:215–219.

5.Pashley NRT. Congenital anomalies of the nose. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LE, et al., eds. Otolaryngology— Head and Neck Surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1993:702–712.

6.Kawamoto HK. Rare craniofacial clefts. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1990:2922–2973.

7.Hinderer KH. Nasal problems in children. Pediatr Ann. 1976;5:499–509.

8.Baraitser M, Winter R. A Colour Atlas of Clinical Genetics. London: Wolfe Medical Publications; 1983.

9.Johnston MC. Embryology of the head and neck. In: McCarthy JG, ed.Plastic Surgery.Philadelphia:W.B.Saunders;1990:2451–2495.

10.Jackson IT, Fasching MC. Secondary deformities of cleft lip, nose and cleft palate. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1990:2771–2877.

11.Holmstrom H. Clinical and pathologic features of maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder’s syndrome): significance of the prenasal fossa on etiology. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;87:559–567.

12.Demas PN, Braun TW. Simultaneous reconstruction of maxillary and nasal deformity in a patient with Binder’s syndrome (maxillonasal dysplasia). J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:83–86.

13.McCarthy JG, Epstein FJ, Wood-Smith D. Craniosynostosis. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1990:3013–3053.

14.Tessier P. Anatomical classification of facial, craniofacial and latero-facial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976;4:69–92.

15.JacksonIT,TannerNSB,HideTAH.Frontonasalencephalocele— “long nose hypertelorism.” Ann Plast Surg. 1983;11:490–500.

J.G. Hunter

16.David DJ, Sheffield L, Simpson D, et al. Frontoethmoidal meningoencephaloceles: morphology and treatment. Br J Plast Surg. 1984;37:271–284.

17.Kelly JH, Strome M, Hall B. Surgical update on nasal dermoids. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:239–242.

18.Gray LP. Prevention and treatment of septal deformity in infancy and childhood. Rhinology. 1977;15:183–191.

19.Kern EB. Acute nasal trauma. In: Rees TD, Baker DC, Tabbal N, eds. Rhinoplasty, Problems and Controversies. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby; 1988:392–396.

20.Hunter JG. Pediatric maxillofacial trauma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1992;39:1127–1143.

21.Illum P. Long term results after treatment of nasal fractures. J Laryngol Otol. 1986;100:273–277.

22.Illum P, Kristensen S, Jorgensen K, et al. Role of fixation in the treatment of nasal fractures. Clin Otolaryngol. 1983;8:191–195.

23.Burget GC, Menick FJ. Nasal reconstruction: seeking a fourth dimension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:145–157.

24.DeSanto LW. Neoplasms. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LE, eds. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1993:754–764.

25.Bise RN, Jackson IT, Smit R. Nasal bone hemangiomas: rare entities treatable by craniofacial approach. Br J Plast Surg. 1991;44:206–209.

26.McDonald TJ. Manifestations of systemic disease. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LE, et al., eds. Otolaryn- gology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1993:713–722.

27.Sercarz JA, Strasnick B, Newman A, et al. Midline nasal destruction in cocaine abusers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991; 105:694–701.

28.Mattson-Gates G, Jabs AD, Hugo NE. Perforation of the hard palate associated with cocaine abuse. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;26: 466–468.

29.Rees T. Secondary rhinoplasty: basic considerations. In: Rees TD, Baker DC, Tabbal N, eds. Rhinoplasty, Problems and Controversies. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby; 1988:292–298.

30.Labrakis G. The universal of early childhood: nature’s aid in understanding the supratip deformity and its correction. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29:55–57.

31.Mulliken JB, Kaban LB, Evans CA, et al. Facial skeletal changes following hypertelorism correction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986; 77:7–16.