- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Introduction

- •2. Evaluation of the Craniomaxillofacial Deformity Patient

- •3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification

- •4. Etiology of Skeletal Malocclusion

- •5. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Traumatic Defects

- •6. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Review of Nasal Deformities

- •7. Review of Benign Tumors of the Maxillofacial Region and Considerations for Bone Invasion

- •8. Oral Malignancies: Etiology, Distribution, and Basic Treatment Considerations

- •9. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Infections: Etiologies, Distributions, and Associated Defects

- •11. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Healing, Biomechanics, and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •12. Metal for Craniomaxillofacial Internal Fixation Implants and Its Physiological Implications

- •13. Bioresorbable Materials for Bone Fixation: Review of Biological Concepts and Mechanical Aspects

- •14. Advanced Bone Healing Concepts in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Bone Surgery

- •15. The ITI Dental Implant System

- •16. Localized Ridge Augmentation Using Guided Bone Regeneration in Deficient Implant Sites

- •17. The ITI Dental Implant System in Maxillofacial Applications

- •18. Maxillary Sinus Grafting and Osseointegration Surgery

- •19. Computerized Tomography and Its Use for Craniomaxillofacial Dental Implantology

- •20B. Atlas of Cases

- •21A. Prosthodontic Considerations in Dental Implant Restoration

- •21B. Overdenture Case Reports

- •22. AO/ASIF Mandibular Hardware

- •23. Aesthetic Considerations in Reconstructive and Corrective Craniomaxillofacial Bone Surgery

- •24. Considerations for Reconstruction of the Head and Neck Oncologic Patient

- •25. Autogenous Bone Grafts in Maxillofacial Reconstruction

- •26. Current Practice and Future Trends in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Microvascular Bone Surgery

- •27. Considerations in the Fixation of Bone Grafts for the Reconstruction of Mandibular Continuity Defects

- •28. Indications and Technical Considerations of Different Fibula Grafts

- •29. Soft Tissue Flaps for Coverage of Craniomaxillofacial Osseous Continuity Defects with or Without Bone Graft and Rigid Fixation

- •30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting

- •31. Microsurgical Reconstruction of Large Defects of the Maxilla, Midface, and Cranial Base

- •32. Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle

- •33. Problems Related to Mandibular Condylar Prosthesis

- •34. Reconstruction of Defects of the Mandibular Angle

- •35. Mandibular Body Reconstruction

- •36. Marginal Mandibulectomy

- •37. Reconstruction of Extensive Anterior Defects of the Mandible

- •38. Radiation Therapy and Considerations for Internal Fixation Devices

- •39. Management of Posttraumatic Osteomyelitis of the Mandible

- •40. Bilateral Maxillary Defects: THORP Plate Reconstruction with Removable Prosthesis

- •41. AO/ASIF Craniofacial Fixation System Hardware

- •43. Orbital Reconstruction

- •44. Nasal Reconstruction Using Bone Grafts and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •46. Orthognathic Examination

- •47. Considerations in Planning for Bimaxillary Surgery and the Implications of Rigid Internal Fixation

- •48. Reconstruction of Cleft Lip and Palate Osseous Defects and Deformities

- •49. Maxillary Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •50. Mandibular Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •51. Genioplasty Techniques and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •52. Long-Term Stability of Maxillary and Mandibular Osteotomies with Rigid Internal Fixation

- •53. Le Fort II and Le Fort III Osteotomies for Midface Reconstruction and Considerations for Internal Fixation

- •54. Craniofacial Deformities: Introduction and Principles of Management

- •55. The Effects of Plate and Screw Fixation on the Growing Craniofacial Skeleton

- •56. Calvarial Bone Graft Harvesting Techniques: Considerations for Their Use with Rigid Fixation Techniques in the Craniomaxillofacial Region

- •57. Crouzon Syndrome: Basic Dysmorphology and Staging of Reconstruction

- •58. Hemifacial Microsomia

- •59. Orbital Hypertelorism: Surgical Management

- •60. Surgical Correction of the Apert Craniofacial Deformities

- •Index

30

Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting

Christian Lindqvist

Reconstruction of the temporomandibular articulation is one of the most demanding challenges in maxillofacial surgery. The goals include not only rehabilitation of the complex mechanism of the normal joint, but restoration of facial symmetry, occlusion, and mastication. As advanced temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disease can lead to disturbances in these features and functions, this often constitutes major indications for arthroplastic procedures. The alleviation of pain is also of great importance, especially in the considerations for surgical treatment of degenerative joint disease. In children, mandibular growth imposes additional constraints on the reconstructive process.

Indications

The most common indications for TMJ arthroplasty are various forms of ankylosis, which cause restriction of mouth opening and disturbed masticatory function (Table 30.1). In most cases, trauma or rheumatoid disease is responsible for the development of ankylosis.1–3 Today, middle-ear infections and osteomyelitis are infrequent causes of ankylosis. Various forms of dysplasia and mandibular deformity can also constitute indications for joint arthroplasty, but with such conditions additional mandibular and maxillary surgery is often necessary.4 Tumors of the mandibular condyle are rare indications for TMJ arthroplasty. Oral cancer operations that require disarticulation of the condyle may necessitate combined extracapsular mandibular and joint reconstruction.

Several methods have been advocated for the treatment of restricted TMJ mobility. The most common method has been interposition arthroplasty. This was the mainstay of the treatment of ankylosis for more than 100 years. However, problems associated with interpositional arthroplasty can have an adverse effect on the results. When alloplastic materials have been used, the problems of articulation, stabilization, and fixation of the graft and foreign-body reactions have sometimes had detrimental effects.

Autogenous Arthroplasty

Several autogenous tissues have been used for replacement grafting of the mandibular condyle. Iliac bone, fibular head, metatarsal bone, metatarsophalangeal joint, clavicle, and sternoclavicular joints, together with orthoptic allografts, have all proved to be successful in restoring lost function of the temporomandibular articulation.5–11

Costochondral Arthroplasty

Gillies was probably the first to use a costochondral graft for this purpose in 1920.12 Since then, a number of authors have recommended autogenous costochondral grafts for congenital dysplasia, ankylosis, osteoarthritis, neoplastic disease, and posttraumatic dysfunction of the TMJ.12–19

Advantages

The advantages of costochondral grafting are the biological and anatomic similarities to the condyle, low morbidity and regeneration of donor sites, and a demonstrated growth potential in juveniles.19,20 Several experimental studies have demonstrated that rib cartilage has characteristics similar to those of the mandibular condyle.19,21,22 This makes it more likely that growth adaptation and function in the new site will occur.

Disadvantages

In spite of the ideal intrinsic and adaptive growth characteristics of the costochondral junction, there are also difficulties associated with rib grafting, the most commonly encountered of which have been pneumothorax and hemothorax, pain, infection, and uncontrolled and unpredictable growth.12,18,20,23

Radiology

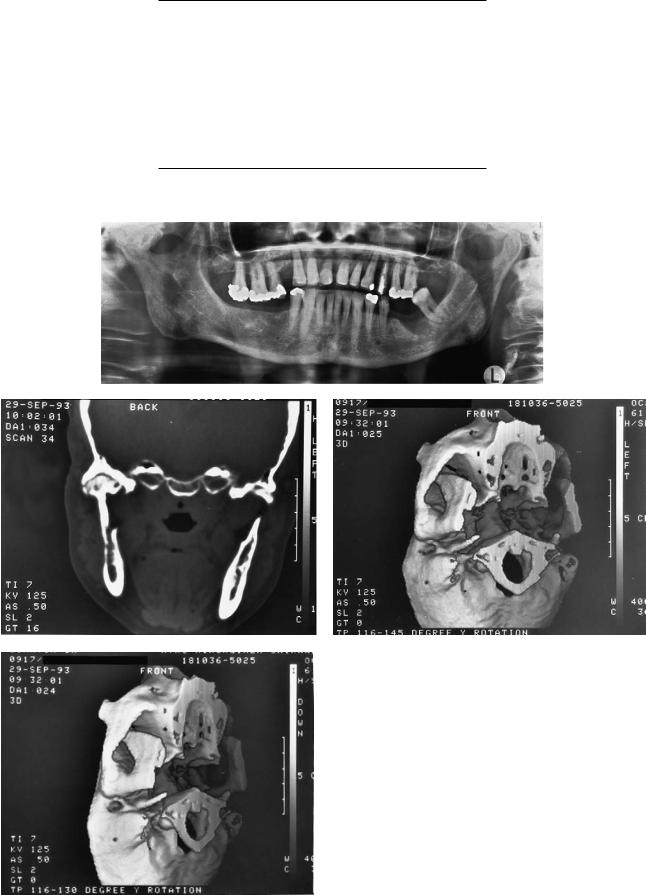

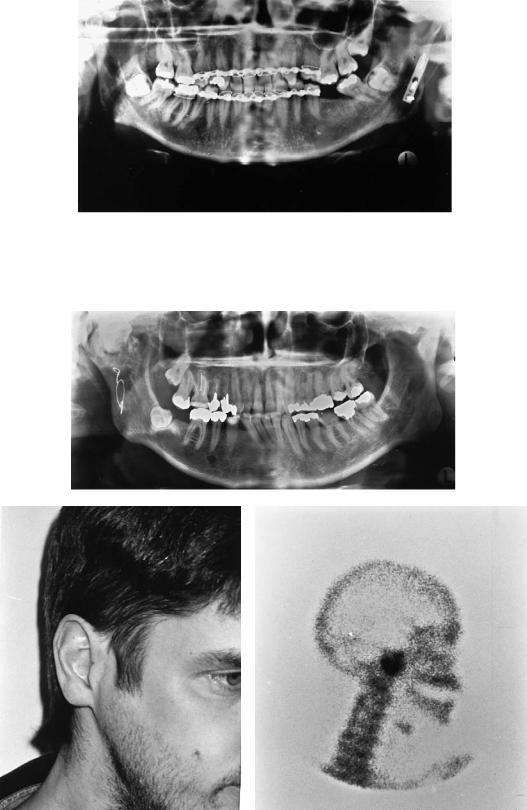

Preoperative radiologic evaluation of the joint usually includes panoramic images and twoand three-dimensional computed tomographic (CT) reconstructions (Figure 30.1).24

343

TABLE 30.1 Indications for arthroplasty.

Ankylosis

Traumatic

Rheumatoid

Arthritic

Postinfection

Tumors

Benign

Malignant

Dysplasia

Hypoplasia

Hyperplasia

Osteomyelitis

a

b |

c |

d

FIGURE 30.1 (a) Panoramic image of 57-year-old woman with ankylosis of right TMJ due to unknown reason. (b) Two-dimensional CT. (c,d) Three-dimensional CT. The extent of the ankylotic process is clearly shown in the CT scans.

30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting |

345 |

a

b |

c |

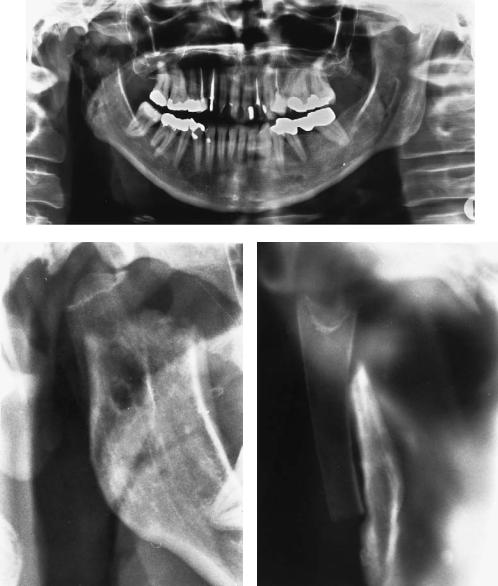

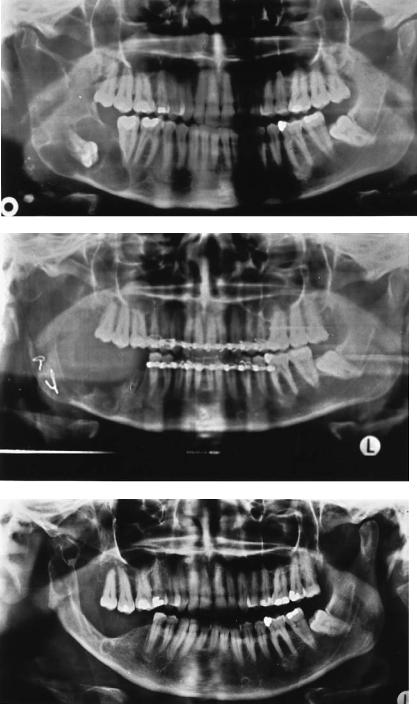

FIGURE 30.2 (a) Postoperative radiograph of patient with costochondral arthroplasty to the right. Graft fixed with polylactide screws. (b) Detailed lateral view. (c) Detailed posteroanterior view. These examinations are useful in follow-up.

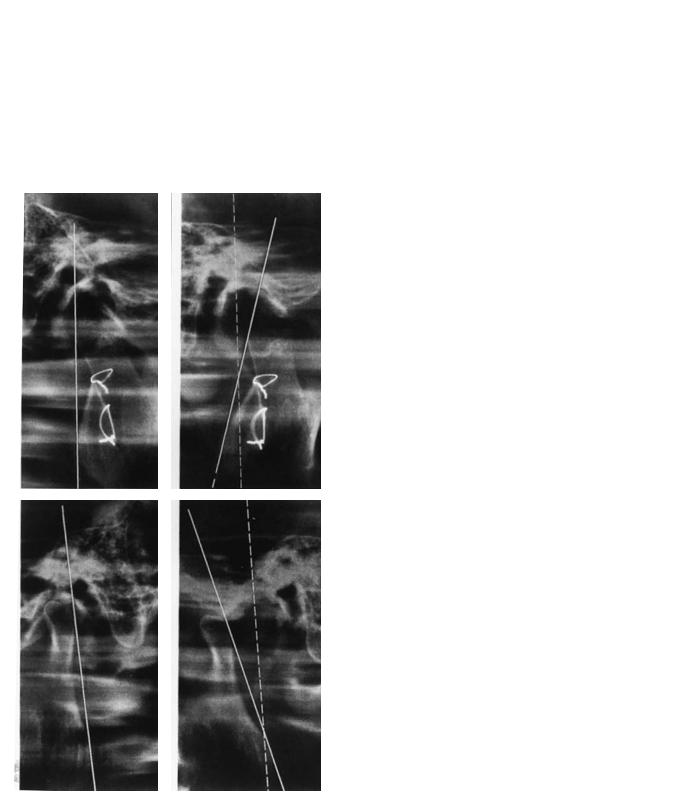

Panoramic examinations taken with image layer programs designed especially for the temporomandibular joint in lateral and posteroanterior projection are useful (Figure 30.2).1,25,26 Examinations that include imaging both joints at the same exposure (Zonarc Instrumentarium, Finland) or detailed images of a single joint (Scanora Orion Corp., Soredex, Finland) can be used. A conventional panoramic radiograph is also usually included in the examination.

Condylar translation can be measured on the TMJ lateral panoramic images taken with the mouth closed and open, and the rotational movement can also be evaluated.25

Plain films and conventional tomography are of limited value in preoperative evaluation of the joint.24

Our experience is limited regarding magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI). Its use should be limited to patients not operated upon earlier because even minute metal debris from tools (e.g., drills), produce large artifacts that deteriorate the image over a large area.

Operative Procedure

During operation, the TMJ is exposed, usually by a submandibular or retromandibular and/or a preauricular (extended in some cases to a bicoronal) approach, and the condylar head (ankylotic segment) is resected. This is the most important and usually most difficult stage of the operation, because often when ankylosis is present the bone mass can be very large and to attempt complete removal might be dan-

346 |

C. Lindqvist |

|

sary. It is fixed laterally with two or three 2.7-mm steel, tita- |

|

nium, or polylactide (PLLA) lag screws (Figure 30.5). Some- |

|

times the rib is very soft and washers have to be used to en- |

|

large the area of pressure (Figure 30.6).1 Particularly in cases |

|

where the mandible is retrognathic and advanced forward with |

|

simultaneous arthroplasty, the rib can be positioned transver- |

|

sally to the dorsal side of the ramus (Figure 30.7),27 and graft |

|

fixation is obtained with miniplates. It is also possible to fix |

|

the graft laterally by one miniplate and 2.0-mm bicortical |

|

screws (Figure 30.8).28 Because the rib can occasionally be |

|

very soft and thin, fixation (either screw or miniplate) does |

|

not always provide enough stability for immediate mandibu- |

FIGURE 30.3 The cartilaginous end of the rib is shaped to match the |

lar mobilization. Intermaxillary fixation (IMF) might be nec- |

temporal fossa. |

essary in some cases for 2 to 3 weeks. TMJ arthroplasty can |

|

also be performed bilaterally during a single operative pro- |

|

cedure. During the operation it is important that IMF main- |

|

tains the desired occlusion, usually with elastics. The fixation |

gerous.1 Because of the medial vascular anatomy, severe |

has to be released occasionally to check the bite, to confirm |

bleeding can be encountered. Great care must be taken to pre- |

that interferences do not exist and that sufficient maximal in- |

serve the neurovascular bundle of the mandible. In ankylosis |

terincisal opening has been achieved. |

cases, coronoidectomy is often performed, sometimes bilater- |

|

ally. Occasionally, the fossa is lined with the temporal mus- |

Complications |

cle, including fascia. The length of the required graft is deter- |

|

mined, and a portion of rib (usually from the sixth or seventh |

Operative complications are infrequent. In our series on 66 |

rib) is removed via a submammary incision. The pectoral mus- |

arthroplasties1 the external carotid had to be ligated in one |

cles and underlying periosteum are divided, and the required |

patient because of severe bleeding. In one case, pneumotho- |

length of bone with cartilage is exposed and removed. It is |

rax occurred and had to be treated by pleural suction. No chest |

very important not to traumatize the costochondral junction, |

infections or wound breakdowns were recorded.1 |

which in children is often quite fragile and easily separates. |

|

After confirming that the parietal pleura is intact, the wound |

Patient Material |

is closed in layers. The rib is preserved in moistened swabs |

|

until the mandible has been prepared to receive the transplant. |

Between 1969 and 1987, 41 female and 31 male patients un- |

The glenoid fossa is judiciously recontoured with burs and |

derwent 82 nonvascular costochondral arthroplasties at the |

the cartilaginous end of the rib shaped to fit into the fossa |

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Helsinki Uni- |

(Figure 30.3). Prior to the advent of rigid fixation, the rib was |

versity Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland. The mean age of |

usually decorticated to fit into the mandible as an inlay (Fig- |

the patients was 32 years. In nearly half of the cases, anky- |

ure 30.4). The graft was then fixed with two 0.5-mm stain- |

losis was the main indication for the operation. The next most |

less steel wires. Today, decortication of the rib is unneces- |

frequent indications, in descending order, were dysplasia, tu- |

a |

b |

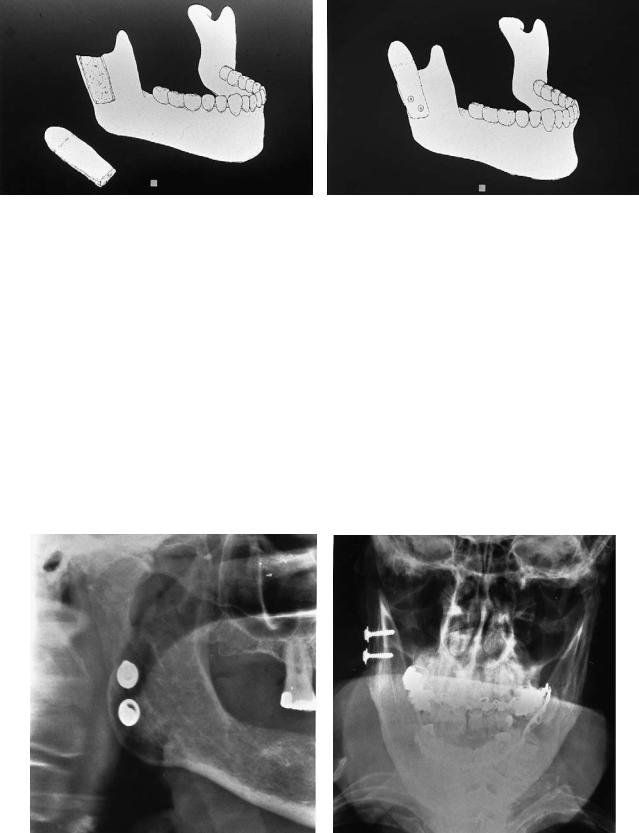

FIGURE 30.4 (a) The decorticated rib and ramus of the mandible. (b) The rib fits into the mandible as an inlay. The graft is fixed with two 0.5-mm stainless steel wires.

30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting |

347 |

a |

b |

FIGURE 30.5 (a) When screws are used for fixation there is no need for decortication of the rib. (b) Rib fixed with two bicortical stainless steel or polylactide screws.

mors, and osteomyelitis. In 8 patients the arthroplasty was performed bilaterally.

Results

Maximal mouth opening increased on average by 13 mm.29 The great majority of the patients (67%) were relieved of their preoperative pain and were able to chew without difficulty. In 56% of the cases with ankylosis, function of the mandible was considered to be good or excellent. Five patients (6.9%), however, suffered subjectively from restricted mouth opening and had difficulties in eating. Two relapses required further opera-

tions, and in one case, total patient neglect of the postoperative training program led to an unsatisfactory result. Very little donor site or recipient site morbidity was observed. Three cases exhibited auriculotemporal syndrome, six had slight weakness of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve, and seven exhibited paresthesia of the lower lip on the operated side. In no case was a pseudoarthrosis between the graft and ramus diagnosed.

Reankylosis after costochondral arthroplasty is rare. However, it is possible that an overgrowth of the cartilagous part with ossification can occur. We have observed this in two patients. In these cases, the joint region can exhibit signs of tumor growth both clinically and radiologically (Figure 30.9). Reoperation is usually indicated.

a |

b |

FIGURE 30.6 (a) Costochondral graft fixed with 2.7-mm bicortical screws together with washers. (b) Anteroposterior view showing the lateral fixation.

348 |

C. Lindqvist |

a

b |

c |

d

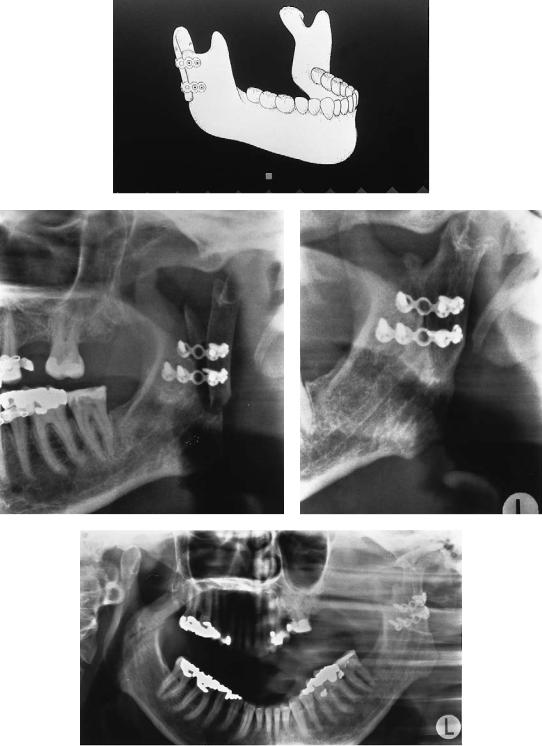

FIGURE 30.7 (a) Transverse fixation of rib with miniplates. (b) Postoperative radiograph of transversely fixed costochondral graft in 44- year-old female patient. (c) JLA of the situation 4 years later. Par-

tial ossification of the chondral part can be observed. (d) Maximal mouth opening shows normal rotation and fairly good translation at the left side.

30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting |

349 |

FIGURE 30.8 Lateral fixation of rib with miniplate and bicortical screws.

a

b |

|

c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 30.9 (a) Radiograph of 38-year-old man who underwent costochondral TMJ arthroplasty to the right 15 years earlier owing to postraumatic TMJ ankylosis. (b) Note preauricular swelling. MIO 12 mm. (c) Bone scan shows extensive uptake.

350 |

C. Lindqvist |

a

b

c

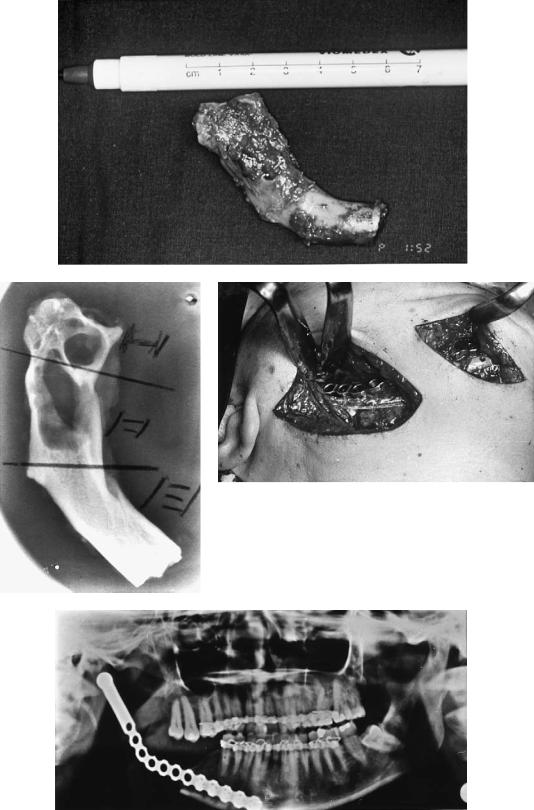

FIGURE 30.10 (a) Keratocyst in right mandible. (b) Reconstruction with costochondral graft after cyst removal. (c) Recurrence in the rib and mandibular body 14 years later. (d) The removed rib with

Recurrent disease can develop in certain cases within a costochondral graft. Figure 30.10 shows the case of a 38- year-old female patient. She had a keratocyst in her right mandible 14 years earlier. This was extirpated and the ra-

tumor. (e) Radiograph of removed rib shows cystic tumor. (f) Reconstruction with titanium condylar plate (note two incisions).

(g) Panoramic image showing the final result.

mus reconstructed with a costochondral graft. A recurrence was noted 14 years later, and the graft was removed and replaced with a titanium reconstruction plate with condylar head.

30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting |

351 |

d

e |

f |

g

FIGURE 30.10 Continued.

352

Late Results

Sixteen patients who underwent operation in our unit before 1982 were followed up clinically and radiologically.25 All of these patients have had unilateral grafts. The mean follow-up time was 9.9 years. Patients were questioned regarding general satisfaction, chewing ability, and facial or joint pain. Other items recorded related to facial motor and sensory function, TMJ clicking or crepitus, joint pain on palpation, maximum mouth opening, lateral excursions, and protrusion of the mandible. The TMJs were radiographed in lateral and posteroanterior projections using a Zonarc (Zonarc, Instrumentarium, Finland) device for panoramic radiography with the patient in the supine position. After the follow-up time, which extended for nearly a decade on average, the mean mouth opening for these 16 patients was 39.4 mm.25 Opening increased postoperatively with time. During the follow-up period, contralateral excursion also increased by an average of 3.1 mm.25 All patients had a symmetrical facial appearance, with the teeth in centric occlusion. On maximal opening, however, 8 patients exhibited a mean deviation of the chin point of 3.5 mm.25

a

c

C. Lindqvist

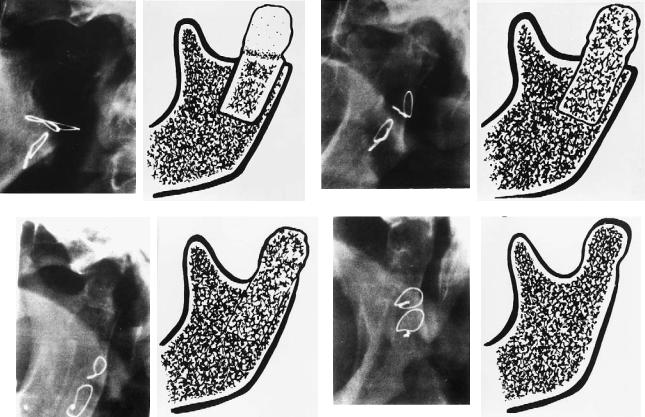

Calcification (ossification) of the transplanted cartilage was graded as follows:

1.Sharp osteochondral margin, similar to postoperative situation with no calcification of the cartilage: 0

2.Slightly noticeable calcification:

3.Considerable calcification but no apparent formation of a condyle:

4.Total or almost total calcification, ossification of the cartilaginous part with joint surface formation, or both:

Radiologically, good bony healing was seen in all patients and no postoperative displacement of the grafts were observed. In six patients, calcification of the cartilaginous region of the rib was total or subtotal, with joint surface formation. In five patients, calcification was considerable but no condyle had been formed during the follow-up period. Only slight calcification was recorded in three patients. In two patients, no mineral deposits were observed. The osteocartilaginous margin was still sharp. As seen on the radiographs, the average translation movement of the rib condyle was 5.0 mm on the operated side and 7.0 mm on the opposite side. The mean angle of rotation was 10°.25 The extent of condy-

b

d

FIGURE 30.11 Different degrees of radiologic calcification and remodeling (adaption) of costochondral grafts to the TMJ. Example of representative radiograph (left). Corresponding schematic drawing (right). (a) Sharp osteochondral margin with no calcification of

cartilage: 0 ( ). (b) Slight calcification: . (c) Considerable calcification without formation of condyle: . (d) Almost total calcification of cartilaginous part with joint surface formation: .

30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting |

353 |

lar translation was significantly greater in the grafts that showed complete adaptation, but no other correlations were found (Figure 30.11–13, Table 30.2).

Several methods have been advocated for the treatment of restricted mobility of the TMJ. The most common method has been interposition arthroplasty, which has been the method of choice for more than 100 years.30 However, there seem to have been several problems with interpositional arthroplasties that may compromise the result. Later when alloplastic

FIGURE 30.12 TMJ lateral panoramic films taken with mouth closed (top and bottom left) and open (top and bottom right). Slight calcification of the cartilage is seen 12 years after reconstruction (top). Translation is 6 mm on operated side and 17 mm on contralateral side. Rotation is 15° on both sides.

FIGURE 30.13 Average maximal mouth opening in 16 patients before and 1, 5, and 10 years after autogenous costochondral TMJ grafts.

materials have been used, problems with articulation, stabilization, and fixation of the polymer, together with foreignbody reactions have had detrimental effects on the results.30 The problem of finding a suitable interpositional autogenous graft still needs to be solved.31 High incidences of postsurgical recurrence of the ankylosis have also been reported.32

Several physical, biomechanical, and animal experiments followed by clinical series have been presented concerning metallic or ceramic joint prostheses.30,33–37 A wide range of commercially available condylar prostheses have produced satisfactory results in the rehabilitation of adult patients suffering from ankylosis. Particularly in severe cases, simultaneous correction of the dental-skeletal problem has been considered an indication for the use of metallic condylar prosthesis. Additionally, there is no need for postsurgical intermaxillary fixation, which must be considered a clear advantage during the early postoperative phase. The use of alloplastic condyles should, however, be restricted to adult patients. Several studies have shown that in children and young adolescents, the costochondral graft has the possibility of responding to the dynamic morphologic changes present during the growth period.14,16,19,20 In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a costochondral graft is also probably safer, owing to the resorption of the glenoid fossa seen in patients reconstructed with bilateral metallic condyles.30,36 Whether this holds true for patients with ankylosing spondylitis or osteoarthritis of the TMJ is unclear.

As early as 195138 osteoarthritis was suggested as an indication for costochondral grafting. It seems that in severe cases the disease leads to a restriction of mouth opening and total deformity of the mandibular condyle. In these cases, when conservative treatment methods have failed, arthroplasty should be considered. It must, however, be emphasized that dysfunction of the TMJ without radiological changes, various

354 |

C. Lindqvist |

TABLE 30.2 Various signs and symptoms in 16 patients with costochondral TMJ arthroplasties according to degree of radiologic adaptation of graft.

|

|

Mean |

Mean |

|

|

Mean |

Mean |

Mean |

Degree of |

|

age |

follow-up |

|

Joint |

opening |

translation |

rotation |

adaptation |

Patients |

(years) |

(years) |

Pain |

noises |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(degrees) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

2 |

36 |

10.6 |

1/2 |

1/2 |

38 |

3.0 |

7.5 |

|

3 |

31 |

9.1 |

1/3 |

— |

48 |

4.3 |

13.3 |

|

5 |

22 |

11.8 |

1/5 |

1/5 |

39 |

4.9 |

9.0 |

|

6 |

37 |

7.0 |

2/6 |

1/6 |

36 |

7.8 |

10.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Totals |

16 |

31 |

9.6 |

5/16 |

3/16 |

40 |

5.0 |

10.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“internal derangements,” and atypical facial neuralgias should not be considered as indications for costochondral arthroplasty. The same holds true for malignant tumors in the condylar region, when disarticulation is performed during the primary ablative procedure. However, when there is no recurrence of tumor within 2 to 3 years after the primary treatment, a costochondral graft can be used for the reconstruction of the condyle. With respect to benign tumors, there do not appear to be any contraindications for costochondral grafting at the primary operation.12

Congenital dysplasia has been a common indication for grafting.12 The term has been used to characterize either excessive or inadequate growth of the condyle. It has been recommended that in cases of hypoplasia or aplasia of the condyle the patients should be operated on at an early age. Also, with respect to hyperplasia, a resection with or without grafting has been advocated.39 In young persons, however, continued growth of the transplant is unpredictable.40 The intrinsic growth potential in transplanted costochondral junction growth centers has been reported several times.20,41,42 Therefore, undercorrection may be justified in juvenile cases.

Primary chronic osteomyelitis of the mandible remains a therapeutic problem. In our patients, the process involved the mandibular condyle and led in some cases to a disturbance of joint function. In fact, osteomyelitis seemed to cause ankylosis of the TMJ in a number of patients.43,44 All these patients also suffered from severe pain, which was refractory to conservative treatment. Costochondral arthroplasty seems to be a solution for these infrequent but problematic cases as good mandibular function was achieved with disappearance of pain. The osteomyelitic process did not appear to affect the transplanted rib during the observation period.

The frequency of early or late complications is rather low and through further refinement of surgical technique, the neurological sequelae (i.e., dysfunction of fifth or seventh cranial nerves) could probably be still further diminished. The harvesting of a rib as a source of bone seems to be safe and relatively easy. The incidence of pneumothorax is low and does not represent a major problem. Proper postoperative physiotherapy is probably important in avoiding chest infections.

Conclusions

Excellent functional and aesthetic results seem to add support to the contention that costochondral grafting is a reliable method for the treatment of TMJ ankylosis owing to several different etiologies. The same seems to hold true with respect to dysplasia of the condyle, deformities of the mandible, and ascending osteomyelitic processes in the mandibular ramus. The results with respect to cases with TMJ dysfunction or atypical facial neuralgia are, however, disappointing.

Similarly, it does not seem advisable to perform costochondral grafting in patients with malignant tumors of the condyle during the primary operation. The frequency of operative complications is rather low at both the donor and the recipient sites.

References

1.Lindqvist C, Pihakari A, Tasanen A, et al. Autogenous costochondral grafts in temporomandibular joint arthroplasty. A survey of 66 arthroplasties in 60 patients. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:143–149.

2.Politis C, Fossion E, Bossuyt M. The use of costochondral grafts in arthroplasty of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1987;15:345–354.

3.Kaban LB, Perrott DH, Fisher K. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1145–1151.

4.Posnick JC, Goldstein JA. Surgical management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis in the pediatric population. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:791–798.

5.Smith AE, Robinson M. A new surgical procedure in bilateral reconstruction of condyles utilizing iliac bone grafts and creation of new joints by means of nonelectrolytic metal: a preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1952;9:393–409.

6.Entin MA. Reconstruction in congenital deformity of the temporomandibular components. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1958;6:461– 469.

7.Ware WH, Taylor RC. Growth centre transplantation to replace damaged mandibular condyles. J Am Dent Assoc. 1966;73:128– 137.

8.Snyder CC, Levine GA, Dingman DL. Trial of a sternoclavicular whole joint graft as a substitute for the temporomandibular

30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting |

355 |

joint. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;48:447–452.

9.Matukas VJ, Szymela J, Schmidt JF. Surgical treatment of bony ankylosis in a child using composite cartilage-bone iliac crest grafts. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:903–905.

10.Siemssen SO. Temporomandibular arthroplasty by transfer of the sterno-clavicular joint on a muscle pedicle. Br J Plast Surg. 1982;35:225–238.

11.Plotnikow NA. Personal communication; 1984.

12.MacIntosh RB, Henny FA. A spectrum of application of autogenous costochondral grafts. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977;5:257–267.

13.Obwegeser HL. Simultaneous resection and reconstruction of parts of the mandible via the intraoral route in patients with and without gross infections. Oral Surg. 1966;21:693–705.

14.Kennett S. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis: the rationale for grafting in the young patient. J Oral Surg. 1973;31:744–748.

15.Freihofer HP, Perko MA. Simultaneous reconstruction of the area of the temporomandibular joint including the ramus of the mandible in a posttraumatic case. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976; 4:124–128.

16.Tasanen A, Leikomaa H. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint of a child. Report of a case. Int J Oral Surg. 1977;6:95–99.

17.Tasanen A, Rissanen H. Costochondral grafting in temporomandibular joint arthroplasty (Abstract). Proc Finn Dent Soc Suppl, II. 1980;76:24.

18.James DR, Irvine GH. Autogenous rib grafts in maxillofacial surgery. J Maxillofac Surg. 1983;11:201–203.

19.Figueroa AA, Gans BJ, Pruzansky S. Long-term follow-up of a mandibular costochondral graft. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:257–268.

20.Ware WH, Brown SL. Growth center transplantation to replace mandibular condyles. J Maxillofac Surg. 1981;9:50–58.

21.Durkin JF, Heeley JD, Irving JT. The cartilage of the mandibular condyle. Oral Sci Rev. 1973;2:29–99.

22.Poswillo D. Experimental reconstruction of the mandibular joint. Int J Oral Surg. 1974;3:400–411.

23.Ware WH, Taylor RC. Cartilaginous growth centers transplanted to replace mandibular condyles in monkeys. J Oral Surg. 1966;24:33–43.

24.Westesson P-L. Diagnostic imaging of oral malignancies. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1993;5:207–227.

25.Lindqvist C, Jokinen J, Paukku P, et al. Adaptation of autogenous costochondral grafts used for temporomandibular joint re-

construction: a long-term clinical and radiologic follow-up.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:465–470.

26.Hallikainen D, Paukku P. Panoramic zonography. In: DelBalso A, ed. Maxillofacial Imaging. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1990:1–33.

27.Obeid G, Guttenberg SA, Connole PW. Costochondral grafting

in condylar replacement and mandibular reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;48:177–182.

28. Mosby EL, Hiatt WR. A technique of fixation of costochondral grafts for reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint.

J Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:209–211.

29.Lindqvist C. TMJ reconstruction and rehabilitation using costochondral and alloplastic grafts. Abstract. SFOMK 25th Anniversary Conference, Nyborg Strand, Denmark. 1990:16–17.

30.Kent JN, Misiek DJ, Akin RK, et al. Temporomandibular joint condylar prosthesis: a ten year report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:245–254.

31.Moorthy AP, Finch LD. Interpositional arthroplasty for ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:545–552.

32.Scheunemann H, Schmidseder R. Gibt es bei der Kiefergelenkankylose eine Standardoperation? In: Schuchardt K, Schwenzer N, eds. Fortschritte der Kieferund Gesichtschirurgie.

Stuttgart: Thieme; 1980:25–109.

33.Fuchs M, Rolffs J, Voy E-D. Tierexperimentelle Untersuchungen zu einer Kiefergelenkendoprothese aus Aluminiumoxidkeramik. In: Schuchardt K, Schwenzer N, eds. Fortschritte der Kieferund Gesichtschirurgie. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1980:25–142.

34.Sonnenburg I, Sonnenburg M, Fethke K. Totalersatz des Kiefergelenkes durch alloplastisches Material. Stomatol DDR. 1982;32:178–185.

35.Raveh J, Stich H, Sutter F, et al. Use of the titanium-coated hollow screw and reconstruction plate system in bridging of lower jaw defects. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:281–294.

36.Lindqvist C, Söderholm A-L, Hallikainen D, et al. Erosion and heterotopic bone formation after alloplastic TMJ reconstruction.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:942–949.

37.Kent JN, Block MS, Halpern J, et al. Update of the Vitek partial and total temporomandibular joint system. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:408–415.

38.Longacre JJ, Gilbey RF. Further observations on use of autogenous cartilage grafts in arthroplasty of temporomandibular joint. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1952;10:238–247.

39.Steinhäuser EW. Kondylektomie oder korrektive Osteotomie bei der kondylären Hyperplasie. In: Schuchardt K, Schwenzer N, eds. Fortschritte der Kieferund Gesichtschirurgie. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1980;25:132–135.

40.Peltomäki T. Growth of a costochondral graft in the rat temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:851–857.

41.Ware WH, Taylor RC. Replantation of growing mandibular condyles in rhesus monkeys. J Oral Surg. 1965;19:669–677.

42.Peltomäki T, Isotupa K. The costochondral graft: a solution or a source of facial asymmetry in growing children. A case report. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1991;87:167–176.