- •Public Administration And Public Policy

- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •About The Authors

- •Comments On Purpose and Methods

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Culture

- •1.3 Colonial Legacies

- •1.3.1 British Colonial Legacy

- •1.3.2 Latin Legacy

- •1.3.3 American Legacy

- •1.4 Decentralization

- •1.5 Ethics

- •1.5.1 Types of Corruption

- •1.5.2 Ethics Management

- •1.6 Performance Management

- •1.6.2 Structural Changes

- •1.6.3 New Public Management

- •1.7 Civil Service

- •1.7.1 Size

- •1.7.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •1.7.3 Pay and Performance

- •1.7.4 Training

- •1.8 Conclusion

- •Contents

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Historical Developments and Legacies

- •2.2.1.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of King as Leader

- •2.2.1.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.1.3 Third Legacy: Traditions of Hierarchy and Clientelism

- •2.2.1.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition of Reconciliation

- •2.2.2.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of Bureaucratic Elites as a Privileged Group

- •2.2.2.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.2.3 Third Legacy: The Practice of Staging Military Coups

- •2.2.2.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition for Military Elites to be Loyal to the King

- •2.2.3.1 First Legacy: Elected Politicians as the New Political Boss

- •2.2.3.2 Second Legacy: Frequent and Unpredictable Changes of Political Bosses

- •2.2.3.3 Third Legacy: Politicians from the Provinces Becoming Bosses

- •2.2.3.4 Fourth Legacy: The Problem with the Credibility of Politicians

- •2.2.4.1 First Emerging Legacy: Big Businessmen in Power

- •2.2.4.2 Second Emerging Legacy: Super CEO Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.4.3 Third Emerging Legacy: Government must Serve Big Business Interests

- •2.2.5.1 Emerging Legacy: The Clash between Governance Values and Thai Realities

- •2.2.5.2 Traits of Governmental Culture Produced by the Five Masters

- •2.3 Uniqueness of the Thai Political Context

- •2.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •3.1 Thailand Administrative Structure

- •3.2 History of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.2.1 Thailand as a Centralized State

- •3.2.2 Towards Decentralization

- •3.3 The Politics of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.3.2 Shrinking Political Power of the Military and Bureaucracy

- •3.4 Drafting the TAO Law 199421

- •3.5 Impacts of the Decentralization Reform on Local Government in Thailand: Ongoing Challenges

- •3.5.1 Strong Executive System

- •3.5.2 Thai Local Political System

- •3.5.3 Fiscal Decentralization

- •3.5.4 Transferred Responsibilities

- •3.5.5 Limited Spending on Personnel

- •3.5.6 New Local Government Personnel System

- •3.6 Local Governments Reaching Out to Local Community

- •3.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Corruption: General Situation in Thailand

- •4.2.1 Transparency International and its Corruption Perception Index

- •4.2.2 Types of Corruption

- •4.3 A Deeper Look at Corruption in Thailand

- •4.3.1 Vanishing Moral Lessons

- •4.3.4 High Premium on Political Stability

- •4.4 Existing State Mechanisms to Fight Corruption

- •4.4.2 Constraints and Limitations of Public Agencies

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 History of Performance Management

- •5.2.1 National Economic and Social Development Plans

- •5.2.2 Master Plan of Government Administrative Reform

- •5.3 Performance Management Reform: A Move Toward High Performance Organizations

- •5.3.1 Organization Restructuring to Increase Autonomy

- •5.3.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.3 Knowledge Management Toward Learning Organizations

- •5.3.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.3.5 Challenges and Lessons Learned

- •5.3.5.1 Organizational Restructuring

- •5.3.5.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.5.3 Knowledge Management

- •5.3.5.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.4.4 Outcome of Budgeting Reform: The Budget Process in Thailand

- •5.4.5 Conclusion

- •5.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •6.1.1 Civil Service Personnel

- •6.1.2 Development of the Civil Service Human Resource System

- •6.1.3 Problems of Civil Service Human Resource

- •6.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •6.2.1 Main Feature

- •6.2.2 Challenges of Recruitment and Selection

- •6.3.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.2 Salary Management

- •6.4.2.2 Performance Management and Salary Increase

- •6.4.3 Position Allowance

- •6.4.5 National Compensation Committee

- •6.4.6 Retirement and Pension

- •6.4.7 Challenges in Compensation

- •6.5 Training and Development

- •6.5.1 Main Feature

- •6.5.2 Challenges of Training and Development in the Civil Service

- •6.6 Discipline and Merit Protection

- •6.6.1 Main Feature

- •6.6.2 Challenges of Discipline

- •6.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •English References

- •Contents

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Setting and Context

- •7.3 Malayan Union and the Birth of the United Malays National Organization

- •7.4 Post Independence, New Economic Policy, and Malay Dominance

- •7.5 Centralization of Executive Powers under Mahathir

- •7.6 Administrative Values

- •7.6.1 Close Ties with the Political Party

- •7.6.2 Laws that Promote Secrecy, Continuing Concerns with Corruption

- •7.6.3 Politics over Performance

- •7.6.4 Increasing Islamization of the Civil Service

- •7.7 Ethnic Politics and Reforms

- •7.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 System of Government in Malaysia

- •8.5 Community Relations and Emerging Recentralization

- •8.6 Process Toward Recentralization and Weakening Decentralization

- •8.7 Reinforcing Centralization

- •8.8 Restructuring and Impact on Decentralization

- •8.9 Where to Decentralization?

- •8.10 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia: General Observations

- •9.2.1 Factors of Corruption

- •9.3 Recent Corruption Scandals

- •9.3.1 Cases Involving Bureaucrats and Executives

- •9.3.2 Procurement Issues

- •9.4 Efforts to Address Corruption and Instill Ethics

- •9.4.1.1 Educational Strategy

- •9.4.1.2 Preventive Strategy

- •9.4.1.3 Punitive Strategy

- •9.4.2 Public Accounts Committee and Public Complaints Bureau

- •9.5 Other Efforts

- •9.6 Assessment and Recommendations

- •9.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •10.1 History of Performance Management in the Administrative System

- •10.1.1 Policy Frameworks

- •10.1.2 Organizational Structures

- •10.1.2.1 Values and Work Ethic

- •10.1.2.2 Administrative Devices

- •10.1.2.3 Performance, Financial, and Budgetary Reporting

- •10.2 Performance Management Reforms in the Past Ten Years

- •10.2.1 Electronic Government

- •10.2.2 Public Service Delivery System

- •10.2.3 Other Management Reforms

- •10.3 Assessment of Performance Management Reforms

- •10.4 Analysis and Recommendations

- •10.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.2.1 Public Service Department

- •11.2.2 Public Service Commission

- •11.2.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •11.2.4 Malaysian Administrative Modernization and Management Planning Unit

- •11.2.5 Administrative and Diplomatic Service

- •11.4 Civil Service Pension Scheme

- •11.5 Civil Service Neutrality

- •11.6 Civil Service Culture

- •11.7 Reform in the Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.2.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.3.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.3.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.4.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.4.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.5.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.5.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.6.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.6.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.7 Public Administration and Society

- •12.7.1 Public Accountability and Participation

- •12.7.2 Administrative Values

- •12.8 Societal and Political Challenge over Bureaucratic Dominance

- •12.9 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.3 Constitutional Framework of the Basic Law

- •13.4 Changing Relations between the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •13.4.1 Constitutional Dimension

- •13.4.1.1 Contending Interpretations over the Basic Law

- •13.4.1.3 New Constitutional Order in the Making

- •13.4.2 Political Dimension

- •13.4.2.3 Contention over Political Reform

- •13.4.3 The Economic Dimension

- •13.4.3.1 Expanding Intergovernmental Links

- •13.4.3.2 Fostering Closer Economic Partnership and Financial Relations

- •13.4.3.3 Seeking Cooperation and Coordination in Regional and National Development

- •13.4.4 External Dimension

- •13.5 Challenges and Prospects in the Relations between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •References

- •Contents

- •14.1 Honesty, Integrity, and Adherence to the Law

- •14.2 Accountability, Openness, and Political Neutrality

- •14.2.1 Accountability

- •14.2.2 Openness

- •14.2.3 Political Neutrality

- •14.3 Impartiality and Service to the Community

- •14.4 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Brief Overview of Performance Management in Hong Kong

- •15.3.1 Measuring and Assessing Performance

- •15.3.2 Adoption of Performance Pledges

- •15.3.3 Linking Budget to Performance

- •15.3.4 Relating Rewards to Performance

- •15.4 Assessment of Outcomes of Performance Management Reforms

- •15.4.1 Are Departments Properly Measuring their Performance?

- •15.4.2 Are Budget Decisions Based on Performance Results?

- •15.4.5 Overall Evaluation

- •15.5 Measurability of Performance

- •15.6 Ownership of, and Responsibility for, Performance

- •15.7 The Politics of Performance

- •15.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Structure of the Public Sector

- •16.2.1 Core Government

- •16.2.2 Hybrid Agencies

- •16.2.4 Private Businesses that Deliver Public Services

- •16.3 Administrative Values

- •16.4 Politicians and Bureaucrats

- •16.5 Management Tools and their Reform

- •16.5.1 Selection

- •16.5.2 Performance Management

- •16.5.3 Compensation

- •16.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 The Philippines: A Brief Background

- •17.4 Philippine Bureaucracy during the Spanish Colonial Regime

- •17.6 American Colonial Regime and the Philippine Commonwealth

- •17.8 Independence Period and the Establishment of the Institute of Public Administration

- •17.9 Administrative Values in the Philippines

- •17.11 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Toward a Genuine Local Autonomy and Decentralization in the Philippines

- •18.2.1 Evolution of Local Autonomy

- •18.2.2 Government Structure and the Local Government System

- •18.2.3 Devolution under the Local Government Code of 1991

- •18.2.4 Local Government Finance

- •18.2.5 Local Government Bureaucracy and Personnel

- •18.3 Review of the Local Government Code of 1991 and its Implementation

- •18.3.1 Gains and Successes of Decentralization

- •18.3.2 Assessing the Impact of Decentralization

- •18.3.2.1 Overall Policy Design

- •18.3.2.2 Administrative and Political Issues

- •18.3.2.2.1 Central and Sub-National Role in Devolution

- •18.3.2.2.3 High Budget for Personnel at the Local Level

- •18.3.2.2.4 Political Capture by the Elite

- •18.3.2.3 Fiscal Decentralization Issues

- •18.3.2.3.1 Macroeconomic Stability

- •18.3.2.3.2 Policy Design Issues of the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.3.2.3.4 Disruptive Effect of the Creation of New Local Government Units

- •18.3.2.3.5 Disparate Planning, Unhealthy Competition, and Corruption

- •18.4 Local Governance Reforms, Capacity Building, and Research Agenda

- •18.4.1 Financial Resources and Reforming the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.4.3 Government Functions and Powers

- •18.4.6 Local Government Performance Measurement

- •18.4.7 Capacity Building

- •18.4.8 People Participation

- •18.4.9 Political Concerns

- •18.4.10 Federalism

- •18.5 Conclusions and the Way Forward

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Control

- •19.2.1 Laws that Break Up the Alignment of Forces to Minimize State Capture

- •19.2.2 Executive Measures that Optimize Deterrence

- •19.2.3 Initiatives that Close Regulatory Gaps

- •19.2.4 Collateral Measures on Electoral Reform

- •19.3 Guidance

- •19.3.1 Leadership that Casts a Wide Net over Corrupt Acts

- •19.3.2 Limiting Monopoly and Discretion to Constrain Abuse of Power

- •19.3.3 Participatory Appraisal that Increases Agency Resistance against Misconduct

- •19.3.4 Steps that Encourage Public Vigilance and the Growth of Civil Society Watchdogs

- •19.3.5 Decentralized Guidance that eases Log Jams in Centralized Decision Making

- •19.4 Management

- •19.5 Creating Virtuous Circles in Public Ethics and Accountability

- •19.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today

- •20.3 Past Reform Initiatives of the Philippine Public Administrative System

- •20.4.1 Rebuilding Institutions and Improving Performance

- •20.4.1.1 Size and Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.1.2 Privatization

- •20.4.1.3 Addressing Corruption

- •20.4.1.5 Improving Work Processes

- •20.4.2 Performance Management Initiatives for the New Millennium

- •20.4.2.1 Financial Management

- •20.4.2.2 New Government Accounting System

- •20.4.2.3 Public Expenditure Management

- •20.4.2.4 Procurement Reforms

- •20.4.3 Human Resource Management

- •20.4.3.1 Organizing for Performance

- •20.4.3.2 Performance Evaluation

- •20.4.3.3 Rationalizing the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.3.4 Public Sector Compensation

- •20.4.3.5 Quality Management Systems

- •20.4.3.6 Local Government Initiatives

- •20.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Country Development Context

- •21.3 Evolution and Current State of the Philippine Civil Service System

- •21.3.1 Beginnings of a Modern Civil Service

- •21.3.2 Inventory of Government Personnel

- •21.3.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •21.3.6 Training and Development

- •21.3.7 Incentive Structure in the Bureaucracy

- •21.3.8 Filipino Culture

- •21.3.9 Bureaucratic Values and Performance Culture

- •21.3.10 Grievance and Redress System

- •21.4 Development Performance of the Philippine Civil Service

- •21.5 Key Development Challenges

- •21.5.1 Corruption

- •21.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 History

- •22.3 Major Reform Measures since the Handover

- •22.4 Analysis of the Reform Roadmap

- •22.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •23.1 Decentralization, Autonomy, and Democracy

- •23.3.1 From Recession to Take Off

- •23.3.2 Politics of Growth

- •23.3.3 Government Inertia

- •23.4 Autonomy as Collective Identity

- •23.4.3 Social Group Dynamics

- •23.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Functions and Performance of the Commission Against Corruption of Macao

- •24.2.1 Functions

- •24.2.2 Guidelines on the Professional Ethics and Conduct of Public Servants

- •24.2.3 Performance

- •24.2.4 Structure

- •24.2.5 Personnel Establishment

- •24.3 New Challenges

- •24.3.1 The Case of Ao Man Long

- •24.3.2 Dilemma of Sunshine Law

- •24.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Theoretical Basis of the Reform

- •25.3 Historical Background

- •25.4 Problems in the Civil Service Culture

- •25.5 Systemic Problems

- •25.6 Performance Management Reform

- •25.6.1 Performance Pledges

- •25.6.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.7 Results and Problems

- •25.7.1 Performance Pledge

- •25.7.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.8 Conclusion and Future Development

- •References

- •Contents

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Civil Service System

- •26.2.1 Types of Civil Servants

- •26.2.2 Bureaucratic Structure

- •26.2.4 Personnel Management

- •26.4 Civil Service Reform

- •26.5 Conclusion

- •References

Chapter 20 |

|

Performance Management |

|

Reforms in the Philippines |

|

Ma. Oliva Z. Domingo and Danilo R. Reyes |

|

Contents |

|

20.1 Introduction................................................................................................................... |

398 |

20.2 Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today......................... |

399 |

20.3 Past Reform Initiatives of the Philippine Public Administrative System......................... |

402 |

20.4 The Philippine Experience in Promoting Results-based Management ............................ |

403 |

20.4.1 Rebuilding Institutions and Improving Performance.......................................... |

403 |

20.4.1.1 Size and Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy ............................................. |

404 |

20.4.1.2 Privatization ......................................................................................... |

406 |

20.4.1.3 Addressing Corruption ......................................................................... |

406 |

20.4.1.4 Decentralizing Operations.................................................................... |

407 |

20.4.1.5 Improving Work Processes.................................................................... |

408 |

20.4.2 Performance Management Initiatives for the New Millennium.......................... |

408 |

20.4.2.1 Financial Management ......................................................................... |

408 |

20.4.2.2 New Government Accounting System .................................................. |

409 |

20.4.2.3 Public Expenditure Management.......................................................... |

409 |

20.4.2.4 Procurement Reforms ............................................................................ |

412 |

20.4.3 Human Resource Management ........................................................................... |

413 |

20.4.3.1 Organizing for Performance .................................................................. |

413 |

20.4.3.2 Performance Evaluation......................................................................... |

413 |

20.4.3.3 Rationalizing the Bureaucracy ............................................................... |

414 |

20.4.3.4 Public Sector Compensation.................................................................. |

415 |

20.4.3.5 Quality Management Systems ............................................................... |

416 |

20.4.3.6 Local Government Initiatives ................................................................ |

417 |

20.5 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... |

417 |

References ................................................................................................................................ |

418 |

|

397 |

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

398 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

20.1 Introduction

The problem of bureaucratic performance persists today as an enduring and long-standing concern in the Philippines. As in other countries, both developed and developing, bureaucratic performance in the Philippines has been plagued with recurring issues of bureaucratic competencies, efficiency, accountability, transparency, and responsiveness, among others. Over the years, various reform measures and initiatives in the country have been instituted or adopted to improve the performance of public agencies and instrumentalities, both at the national and local levels.

This chapter discusses performance management reforms that have been launched in response to problems of underperformance of Philippine bureaucracy. Admittedly, the causes of underperforming institutions in the country are many and varied, and perhaps, in some cases agency or sector-specific. Likewise, the causes can be traced or attributed to such factors as organizational ethos and temperaments, human frailties, weak leadership, policy gaps, poor systems and procedures, declining resources, and political intervention, among others.

In an era of growing citizen disenchantment and activism in the management of public affairs, the performance of the bureaucracy has become an important consideration by which the perception and acceptance of government are judged or determined. The years that have been characterized by the expanding involvement and intervention of civil society organizations and various interest and pressure groups in the shaping of policies and the delivery of public goods and services have shown the significance of making bureaucracy work better and perform according to the expectations of its public.

The chapter thus presents at the outset, an overview of Philippine bureaucracy and the problems that beset it. This part provides a quick random discussion of Philippine bureaucracy and the maladies that afflict it. In so doing, it identifies approaches and efforts instituted in the past to make the bureaucracy perform better.

The initiatives introduced during the past 10 years (1999–2009) to address current problems are subsequently discussed. A number of reform measures have been introduced in the Philippines in the various facets and aspects of government operations. These cover important components such as the financial system, mainly auditing and budgeting, expenditures, disbursements and procurement, manpower distribution, and delivery systems. The discussion therefore will attempt to present a number of policies adopted to put across reforms in the areas of audit as exemplified by the introduction of a new government auditing system (NGAS), the reform of the public management expenditure program under the medium-term expenditure framework (MTEF) adopted in the medium-term development plan, the procurement system, through the omnibus procurement law, and efforts to adopt a rightsizing policy to ensure having the appropriate size of personnel manning the bureaucracy.1

1For the purposes of the present discussion, “performance” as it relates to public administration or the bureaucracy can be construed as the efficient, effective, and rational delivery of public goods and services, the creation of opportunities or the exercise of government’s authority in its regulatory and service functions to fulfi ll its mandate to serve and protect the general public interest and welfare. As Van der Walle notes, definitions of performance are should be “composed of performance values that are multifaceted and even sometimes contradictory” such as transparency, responsiveness, sustainability, legitimacy, and sensitivity to gender issues as well as the disabled and vulnerable sectors, among others. He also asserts that any definition should be “acceptable to the widest possible range of actors” (Van de Walle, 2008: 267).

T he term “performance” and “performance management” therefore may mean different things to different administrative systems and people. This chapter follows the definition adopted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which defines performance management as how a government transforms its highest priorities into strategic outputs that are cascaded down to organizations and individuals, such as through improved quality and effectiveness of programs (2001: 10). Many performance management initiatives in the Philippines over the past decade involve financial and human resource management.

©2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Performance Management Reforms in the Philippines 399

20.2Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today

The demands for bureaucracies today to perform and fulfill mandated functions reflect an array of enormous and burgeoning pressures. They involve such realities as marked rising expectations by a potentially alienated or frustrated populace, declining public funds and resources, and such continuing ills as corruption, red tape, low morale, incompetence, and problems of recruiting capable and qualified personnel in a situation where salary levels are low and way below those received by workers in the private sector.

As such, public sector reform in the Philippines has been a continuing concern, like the bureaucracies of other countries, developed or developing, where reform has practically persisted as an enduring and recurring agenda (Reyes, 2009).

The foremost issue perhaps that affects the performance of the bureaucracy and its efficient delivery of services in the Philippines is the size and distribution of manpower in Philippine bureaucracy. The bureaucracy in the Philippines roughly consists of agencies and instrumentalities at the national level of government, namely, regular government departments and its agencies and subdivisions, government-owned and controlled corporations, regulatory bodies, constitutional commissions, and those operating or manning the local levels of government and its instrumentalities. The local government system in the Philippines is comprised of the provincial governments, the chartered cities and municipalities, and special districts as the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) and Metropolitan Manila.

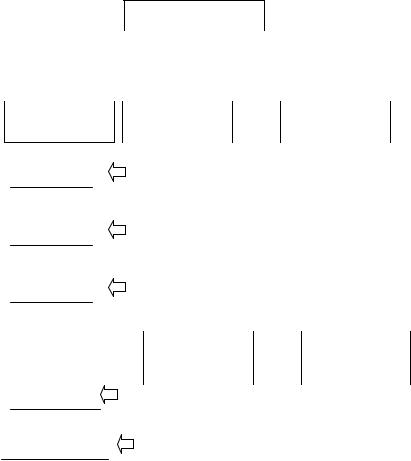

With roughly a little over 1.5 million employees consisting of employees at the national and local levels, as well as the uniformed services (i.e., the Philippine National Police and the Armed Forces of the Philippines), bureaucracy in the country serves an estimated population of about 91 million Filipinos in 2009. It is also over centralized. As can be seen in Figure 20.1, the distribution of personnel is quite lopsided and uneven.2

Most of the civil service personnel are concentrated at the national level, and are mostly employed in the education sector. Only about 23% are employed at the local levels of government, where primary and important interactions with citizens are made and conformably where delivery of basic service is expected to be accomplished.

With undermanned and understaffed employees, particularly at the grassroots or the community levels, it could be said that Philippine bureaucracy is hard put to deliver a good performance compared to other countries. Sto. Tomas (2003: 420), for instance, cites that Canada “has two million civil servants to service a population of about 24 million.” She thus asserts that, “[t]he Philippine bureaucracy may not be the bloated monster it has been pictured to be if we are to factor in the size of the clientele we are serving” (Sto. Tomas, 2003: 424).

Mangahas (1993), in an earlier study, compared and analyzed the ratio of the number of government employees of various developed and developing countries in relation to population. Mangahas, using Civil Service Commission (CSC) estimates of the number of government

2These are estimates based on a report on a publication of the government of the Republic of the Philippines, World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank, 2003. At the time of this study, no updated data exist. Prior to data have been apparently made. Prior to the GRP, WB, and ADB publication, Patricia Sto. Tomas, former chairperson of the Philippine Civil Service Commission (CSC), a constitutional body, decried in fact the lack of “accurate, updated information on the bureaucracy” as bedeviling the civil service (see Sto. Tomas, 2003). It is, however, a safe assumption that the number made in 2001 has been maintained considering government efforts to control the size of the bureaucracy through such downsizing policies as attrition, hiring freeze, non-fi lling of vacant positions, and the abolition of government offices. A related study is that of Mangahas (1993).

©2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

400 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

TOTAL PUBLICEMPLYOMENT 1,531,430

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GOCC/GFI |

|

GENERAL |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

GOVERNMENT |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

90,641 (6%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

1,440,789 (94%) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Armed Forces |

Total Civilian |

Total LGU |

|

National Govt |

|||

124,696 (8%) |

344,576 (23%) |

||

971,517 (63%) |

|||

|

|

Total education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

employment |

|

Education |

|

|

|

Education |

|||

Total health |

|

543,931 |

|

|

|

|

N/A |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

employment |

|

Health |

|

|

|

Health |

|||

Total Police |

|

26,625 |

|

|

|

|

N/A |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

employment |

|

Police |

|

|

|

Police |

|||

|

|

|

111,742 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Civilian National |

|

|

|

LGU |

||

|

|

|

Govt. (excluding |

|

|

|

(excluding |

||

|

|

|

education, health, police) |

|

|

|

education, health, police) |

||

|

|

289,208 |

|

344,576 |

|

||||

Often known as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

the “civil service” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Permanent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Permanent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

950,039 (98%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

249,895 (73%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Casual/contractual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

employees |

|

|

|

|

|

Casual/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Casual/ |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

contractual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

contractual |

|

||||

|

|

|

21,478 (2%) |

|

|

941,681 (27%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 20.1 Public Sector Personnel. Sources: Department of Budget and Management (Republic of the Philippines), Philippine Statistical Yearbook, World Bank Staff Estimates. See Government of the Republic of the Philippines, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank, 2003.

personnel at that time, as well as data on the size of the bureaucracy in the 1980s for other countries, showed that for every 100 of the population, the Philippines had an equivalent of only about 2.3 civil servants, as compared to Malaysia with 4.5, Singapore with 5.4, Australia with 9.8, and Sweden with 14.7. The Philippine figures for civil servant and population ratio compare favorably today with its ASEAN counterparts, such as Singapore and Brunei (NEDA, 2001).

An important concern related to this is dwindling and declining budgets for government expenditure in financing vital programs and projects. Analyzing fiscal and monetary policies in the Philippines, Briones (2003: 559) points out that, “[d]ebt service remains the number one priority item in the budget consistently exceeding allocations for economic and social services since 1983.”

Apparently, as of 2009, the situation has not changed since budgetary allocations in the national appropriations act remain somewhere between 35% and 40% of the total. This is, in fact,

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Performance Management Reforms in the Philippines 401

compounded by problems of a dysfunctional tax administration system where target tax revenues generally fall behind tax collection targets (Briones, 2003; Boncodin, 2003). The problem is further aggravated by leakages stemming from corruption and wastages.

Like other bureaucracies, corruption remains a scourge in the government. Conspicuously contributing to the problem of underperformance in the country is the important problem of graft and corruption. Both political and bureaucratic corruption has undermined the quality and efficiency of services in the Philippines, thus compromising performance.

Over the years, vigorous initiatives have been launched to contain graft and corruption in the Philippines which has hampered performance especially in the efficient delivery of public services in the country. The measures adopted to contain these are many and involve the establishment of anti-corruption agencies as well as streamlining policies and procedures.3

Corrupt practices impair government operations and performance because public funds are siphoned off or drawn away from their intended or mandated use, and diverted to the personal bank accounts of government officials both from the bureaucracy and elected politicians. Corrupt activities that impair or compromise performance are many and creative—rent-seeking bureaucratic officials, bribery, embezzlement of public funds, ghost employees, kickback and overpricing of supplies and services, collusion with suppliers or service providers such as contractors, rigging of bidding processes, and several other methods that are often tolerated and abetted by government officials.

Commissioner Mary Ann Fernandez of the CSC in the Philippines points out that in a span of a little over 50 years, there had been 15 presidential anti-corruption agencies established to combat corruption in the country (Fernandez, 2004).

The magnitude and effects of the corruption problem in the Philippines is further described by Fernandez:

The impact of corruption has been quantified in numerous studies in the country. Last year, the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) estimated that the Philippine government lost almost US$382 million due to fraudulent practices in procurement services and US$1.3 billion for government build-operate-transfer road projects through leakages in transactions and purchases. During the last 20 years, the estimated amount lost due to corruption is US$48 billion. (Fernandez, 2004: 92)

Coupled with these are such problems as poorly established systems and procedures that either open opportunities for corruption or result in red tape (Reyes, 1982). Linked to corruption, rules and regulation, for instance, designed to contain corrupt practices are circumvented or manipulated to intentionally create delays or inaction until a client comes across with a bribe. Thus, unscrupulous bureaucrats may require documentation in various government transactions, which may be onerous and cumbersome, but can be set aside if a client is willing to bribe his way to avoid complying with onerous requirements.4

3The specialized laws that represent measures to contain graft and corruption in the Philippines can be found and compiled in Office of the Ombudsman (2004), as revised. Other pertinent laws, however, are scattered throughout several laws and issuances. There are also a number of studies and commentaries made on graft and corruption in the Philippines, such as Carlos (2004), Alfi ler (1979), and Endriga (1979). A good reference is Carino (1986), who compared and analyzed corrupt practices in selected countries in Asia.

4See Carlos (2004) Chapter V: “What Needs to be Done?” pp. 235–99, for a more detailed discussion of the ills and challenges afflicting Philippine bureaucracy.

©2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC