- •Public Administration And Public Policy

- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •About The Authors

- •Comments On Purpose and Methods

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Culture

- •1.3 Colonial Legacies

- •1.3.1 British Colonial Legacy

- •1.3.2 Latin Legacy

- •1.3.3 American Legacy

- •1.4 Decentralization

- •1.5 Ethics

- •1.5.1 Types of Corruption

- •1.5.2 Ethics Management

- •1.6 Performance Management

- •1.6.2 Structural Changes

- •1.6.3 New Public Management

- •1.7 Civil Service

- •1.7.1 Size

- •1.7.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •1.7.3 Pay and Performance

- •1.7.4 Training

- •1.8 Conclusion

- •Contents

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Historical Developments and Legacies

- •2.2.1.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of King as Leader

- •2.2.1.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.1.3 Third Legacy: Traditions of Hierarchy and Clientelism

- •2.2.1.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition of Reconciliation

- •2.2.2.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of Bureaucratic Elites as a Privileged Group

- •2.2.2.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.2.3 Third Legacy: The Practice of Staging Military Coups

- •2.2.2.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition for Military Elites to be Loyal to the King

- •2.2.3.1 First Legacy: Elected Politicians as the New Political Boss

- •2.2.3.2 Second Legacy: Frequent and Unpredictable Changes of Political Bosses

- •2.2.3.3 Third Legacy: Politicians from the Provinces Becoming Bosses

- •2.2.3.4 Fourth Legacy: The Problem with the Credibility of Politicians

- •2.2.4.1 First Emerging Legacy: Big Businessmen in Power

- •2.2.4.2 Second Emerging Legacy: Super CEO Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.4.3 Third Emerging Legacy: Government must Serve Big Business Interests

- •2.2.5.1 Emerging Legacy: The Clash between Governance Values and Thai Realities

- •2.2.5.2 Traits of Governmental Culture Produced by the Five Masters

- •2.3 Uniqueness of the Thai Political Context

- •2.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •3.1 Thailand Administrative Structure

- •3.2 History of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.2.1 Thailand as a Centralized State

- •3.2.2 Towards Decentralization

- •3.3 The Politics of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.3.2 Shrinking Political Power of the Military and Bureaucracy

- •3.4 Drafting the TAO Law 199421

- •3.5 Impacts of the Decentralization Reform on Local Government in Thailand: Ongoing Challenges

- •3.5.1 Strong Executive System

- •3.5.2 Thai Local Political System

- •3.5.3 Fiscal Decentralization

- •3.5.4 Transferred Responsibilities

- •3.5.5 Limited Spending on Personnel

- •3.5.6 New Local Government Personnel System

- •3.6 Local Governments Reaching Out to Local Community

- •3.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Corruption: General Situation in Thailand

- •4.2.1 Transparency International and its Corruption Perception Index

- •4.2.2 Types of Corruption

- •4.3 A Deeper Look at Corruption in Thailand

- •4.3.1 Vanishing Moral Lessons

- •4.3.4 High Premium on Political Stability

- •4.4 Existing State Mechanisms to Fight Corruption

- •4.4.2 Constraints and Limitations of Public Agencies

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 History of Performance Management

- •5.2.1 National Economic and Social Development Plans

- •5.2.2 Master Plan of Government Administrative Reform

- •5.3 Performance Management Reform: A Move Toward High Performance Organizations

- •5.3.1 Organization Restructuring to Increase Autonomy

- •5.3.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.3 Knowledge Management Toward Learning Organizations

- •5.3.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.3.5 Challenges and Lessons Learned

- •5.3.5.1 Organizational Restructuring

- •5.3.5.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.5.3 Knowledge Management

- •5.3.5.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.4.4 Outcome of Budgeting Reform: The Budget Process in Thailand

- •5.4.5 Conclusion

- •5.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •6.1.1 Civil Service Personnel

- •6.1.2 Development of the Civil Service Human Resource System

- •6.1.3 Problems of Civil Service Human Resource

- •6.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •6.2.1 Main Feature

- •6.2.2 Challenges of Recruitment and Selection

- •6.3.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.2 Salary Management

- •6.4.2.2 Performance Management and Salary Increase

- •6.4.3 Position Allowance

- •6.4.5 National Compensation Committee

- •6.4.6 Retirement and Pension

- •6.4.7 Challenges in Compensation

- •6.5 Training and Development

- •6.5.1 Main Feature

- •6.5.2 Challenges of Training and Development in the Civil Service

- •6.6 Discipline and Merit Protection

- •6.6.1 Main Feature

- •6.6.2 Challenges of Discipline

- •6.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •English References

- •Contents

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Setting and Context

- •7.3 Malayan Union and the Birth of the United Malays National Organization

- •7.4 Post Independence, New Economic Policy, and Malay Dominance

- •7.5 Centralization of Executive Powers under Mahathir

- •7.6 Administrative Values

- •7.6.1 Close Ties with the Political Party

- •7.6.2 Laws that Promote Secrecy, Continuing Concerns with Corruption

- •7.6.3 Politics over Performance

- •7.6.4 Increasing Islamization of the Civil Service

- •7.7 Ethnic Politics and Reforms

- •7.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 System of Government in Malaysia

- •8.5 Community Relations and Emerging Recentralization

- •8.6 Process Toward Recentralization and Weakening Decentralization

- •8.7 Reinforcing Centralization

- •8.8 Restructuring and Impact on Decentralization

- •8.9 Where to Decentralization?

- •8.10 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia: General Observations

- •9.2.1 Factors of Corruption

- •9.3 Recent Corruption Scandals

- •9.3.1 Cases Involving Bureaucrats and Executives

- •9.3.2 Procurement Issues

- •9.4 Efforts to Address Corruption and Instill Ethics

- •9.4.1.1 Educational Strategy

- •9.4.1.2 Preventive Strategy

- •9.4.1.3 Punitive Strategy

- •9.4.2 Public Accounts Committee and Public Complaints Bureau

- •9.5 Other Efforts

- •9.6 Assessment and Recommendations

- •9.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •10.1 History of Performance Management in the Administrative System

- •10.1.1 Policy Frameworks

- •10.1.2 Organizational Structures

- •10.1.2.1 Values and Work Ethic

- •10.1.2.2 Administrative Devices

- •10.1.2.3 Performance, Financial, and Budgetary Reporting

- •10.2 Performance Management Reforms in the Past Ten Years

- •10.2.1 Electronic Government

- •10.2.2 Public Service Delivery System

- •10.2.3 Other Management Reforms

- •10.3 Assessment of Performance Management Reforms

- •10.4 Analysis and Recommendations

- •10.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.2.1 Public Service Department

- •11.2.2 Public Service Commission

- •11.2.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •11.2.4 Malaysian Administrative Modernization and Management Planning Unit

- •11.2.5 Administrative and Diplomatic Service

- •11.4 Civil Service Pension Scheme

- •11.5 Civil Service Neutrality

- •11.6 Civil Service Culture

- •11.7 Reform in the Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.2.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.3.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.3.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.4.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.4.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.5.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.5.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.6.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.6.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.7 Public Administration and Society

- •12.7.1 Public Accountability and Participation

- •12.7.2 Administrative Values

- •12.8 Societal and Political Challenge over Bureaucratic Dominance

- •12.9 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.3 Constitutional Framework of the Basic Law

- •13.4 Changing Relations between the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •13.4.1 Constitutional Dimension

- •13.4.1.1 Contending Interpretations over the Basic Law

- •13.4.1.3 New Constitutional Order in the Making

- •13.4.2 Political Dimension

- •13.4.2.3 Contention over Political Reform

- •13.4.3 The Economic Dimension

- •13.4.3.1 Expanding Intergovernmental Links

- •13.4.3.2 Fostering Closer Economic Partnership and Financial Relations

- •13.4.3.3 Seeking Cooperation and Coordination in Regional and National Development

- •13.4.4 External Dimension

- •13.5 Challenges and Prospects in the Relations between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •References

- •Contents

- •14.1 Honesty, Integrity, and Adherence to the Law

- •14.2 Accountability, Openness, and Political Neutrality

- •14.2.1 Accountability

- •14.2.2 Openness

- •14.2.3 Political Neutrality

- •14.3 Impartiality and Service to the Community

- •14.4 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Brief Overview of Performance Management in Hong Kong

- •15.3.1 Measuring and Assessing Performance

- •15.3.2 Adoption of Performance Pledges

- •15.3.3 Linking Budget to Performance

- •15.3.4 Relating Rewards to Performance

- •15.4 Assessment of Outcomes of Performance Management Reforms

- •15.4.1 Are Departments Properly Measuring their Performance?

- •15.4.2 Are Budget Decisions Based on Performance Results?

- •15.4.5 Overall Evaluation

- •15.5 Measurability of Performance

- •15.6 Ownership of, and Responsibility for, Performance

- •15.7 The Politics of Performance

- •15.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Structure of the Public Sector

- •16.2.1 Core Government

- •16.2.2 Hybrid Agencies

- •16.2.4 Private Businesses that Deliver Public Services

- •16.3 Administrative Values

- •16.4 Politicians and Bureaucrats

- •16.5 Management Tools and their Reform

- •16.5.1 Selection

- •16.5.2 Performance Management

- •16.5.3 Compensation

- •16.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 The Philippines: A Brief Background

- •17.4 Philippine Bureaucracy during the Spanish Colonial Regime

- •17.6 American Colonial Regime and the Philippine Commonwealth

- •17.8 Independence Period and the Establishment of the Institute of Public Administration

- •17.9 Administrative Values in the Philippines

- •17.11 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Toward a Genuine Local Autonomy and Decentralization in the Philippines

- •18.2.1 Evolution of Local Autonomy

- •18.2.2 Government Structure and the Local Government System

- •18.2.3 Devolution under the Local Government Code of 1991

- •18.2.4 Local Government Finance

- •18.2.5 Local Government Bureaucracy and Personnel

- •18.3 Review of the Local Government Code of 1991 and its Implementation

- •18.3.1 Gains and Successes of Decentralization

- •18.3.2 Assessing the Impact of Decentralization

- •18.3.2.1 Overall Policy Design

- •18.3.2.2 Administrative and Political Issues

- •18.3.2.2.1 Central and Sub-National Role in Devolution

- •18.3.2.2.3 High Budget for Personnel at the Local Level

- •18.3.2.2.4 Political Capture by the Elite

- •18.3.2.3 Fiscal Decentralization Issues

- •18.3.2.3.1 Macroeconomic Stability

- •18.3.2.3.2 Policy Design Issues of the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.3.2.3.4 Disruptive Effect of the Creation of New Local Government Units

- •18.3.2.3.5 Disparate Planning, Unhealthy Competition, and Corruption

- •18.4 Local Governance Reforms, Capacity Building, and Research Agenda

- •18.4.1 Financial Resources and Reforming the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.4.3 Government Functions and Powers

- •18.4.6 Local Government Performance Measurement

- •18.4.7 Capacity Building

- •18.4.8 People Participation

- •18.4.9 Political Concerns

- •18.4.10 Federalism

- •18.5 Conclusions and the Way Forward

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Control

- •19.2.1 Laws that Break Up the Alignment of Forces to Minimize State Capture

- •19.2.2 Executive Measures that Optimize Deterrence

- •19.2.3 Initiatives that Close Regulatory Gaps

- •19.2.4 Collateral Measures on Electoral Reform

- •19.3 Guidance

- •19.3.1 Leadership that Casts a Wide Net over Corrupt Acts

- •19.3.2 Limiting Monopoly and Discretion to Constrain Abuse of Power

- •19.3.3 Participatory Appraisal that Increases Agency Resistance against Misconduct

- •19.3.4 Steps that Encourage Public Vigilance and the Growth of Civil Society Watchdogs

- •19.3.5 Decentralized Guidance that eases Log Jams in Centralized Decision Making

- •19.4 Management

- •19.5 Creating Virtuous Circles in Public Ethics and Accountability

- •19.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today

- •20.3 Past Reform Initiatives of the Philippine Public Administrative System

- •20.4.1 Rebuilding Institutions and Improving Performance

- •20.4.1.1 Size and Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.1.2 Privatization

- •20.4.1.3 Addressing Corruption

- •20.4.1.5 Improving Work Processes

- •20.4.2 Performance Management Initiatives for the New Millennium

- •20.4.2.1 Financial Management

- •20.4.2.2 New Government Accounting System

- •20.4.2.3 Public Expenditure Management

- •20.4.2.4 Procurement Reforms

- •20.4.3 Human Resource Management

- •20.4.3.1 Organizing for Performance

- •20.4.3.2 Performance Evaluation

- •20.4.3.3 Rationalizing the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.3.4 Public Sector Compensation

- •20.4.3.5 Quality Management Systems

- •20.4.3.6 Local Government Initiatives

- •20.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Country Development Context

- •21.3 Evolution and Current State of the Philippine Civil Service System

- •21.3.1 Beginnings of a Modern Civil Service

- •21.3.2 Inventory of Government Personnel

- •21.3.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •21.3.6 Training and Development

- •21.3.7 Incentive Structure in the Bureaucracy

- •21.3.8 Filipino Culture

- •21.3.9 Bureaucratic Values and Performance Culture

- •21.3.10 Grievance and Redress System

- •21.4 Development Performance of the Philippine Civil Service

- •21.5 Key Development Challenges

- •21.5.1 Corruption

- •21.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 History

- •22.3 Major Reform Measures since the Handover

- •22.4 Analysis of the Reform Roadmap

- •22.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •23.1 Decentralization, Autonomy, and Democracy

- •23.3.1 From Recession to Take Off

- •23.3.2 Politics of Growth

- •23.3.3 Government Inertia

- •23.4 Autonomy as Collective Identity

- •23.4.3 Social Group Dynamics

- •23.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Functions and Performance of the Commission Against Corruption of Macao

- •24.2.1 Functions

- •24.2.2 Guidelines on the Professional Ethics and Conduct of Public Servants

- •24.2.3 Performance

- •24.2.4 Structure

- •24.2.5 Personnel Establishment

- •24.3 New Challenges

- •24.3.1 The Case of Ao Man Long

- •24.3.2 Dilemma of Sunshine Law

- •24.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Theoretical Basis of the Reform

- •25.3 Historical Background

- •25.4 Problems in the Civil Service Culture

- •25.5 Systemic Problems

- •25.6 Performance Management Reform

- •25.6.1 Performance Pledges

- •25.6.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.7 Results and Problems

- •25.7.1 Performance Pledge

- •25.7.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.8 Conclusion and Future Development

- •References

- •Contents

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Civil Service System

- •26.2.1 Types of Civil Servants

- •26.2.2 Bureaucratic Structure

- •26.2.4 Personnel Management

- •26.4 Civil Service Reform

- •26.5 Conclusion

- •References

Performance Management Reforms in Thailand 103

especially in hospitals, universities, other government agencies in the central administrative system, and state enterprises.

5.3.4 Performance Agreement

The Royal Decree on Good Governance Promotion B.E. 2546 indicates that the government should announce the Government Administration Plan, which relies on a national policy and government agenda. All government agencies have to translate the Government Plan into their own 4-year Performance Plan and annual plan to request an annual budget.

The OPDC has initiated the Performance Agreement as a tool for monitoring and evaluating the performance of government agencies. The concept of the Balanced Scorecard has been applied as a framework of performance evaluation. Then, the OPDC will monitor and evaluate the performance of the agencies based on what was stated in their Agreement. The incentive scheme will be provided in accordance with performance.

In 2007, a total of 310 public sector organizations, including departments, universities, and provinces had performance agreements. The government agencies have to develop their performance agreement, consisting of four perspectives and negotiate with the OPDC to determine the performance indicators and targets to be achieved and the scoring criteria. The agencies have to report their implementation progress in the form of a Self-Assessment Report Card (SAR) at the end of six, nine, and twelve months (OPDC, 2006: 158).

5.3.5 Challenges and Lessons Learned

5.3.5.1 Organizational Restructuring

One reason for the organizational restructuring in the public sector is to increase the autonomy of the organizations so that they will eventually be able to increase their performance. Banpaew Hospital is a successful autonomous hospital that was able to improve its performance after it changed its organizational structure from a government hospital to a public autonomous hospital (Tanchai et al., 2002; Thamtatchaaree et al., 2001). The hospital has efficient services and can provide free eye operations for people in many provinces. Banpaew Hospital signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Phuket Provincial Administration to help them manage the personnel administration in the newly established Phuket Provincial Administration Hospital (Manager, 2008). Additionally, it is the only public hospital that has been capable of taking over a private hospital.

Despite the success of Banpaew Hospital, other autonomous organizations have some limitations. The Budget Act (A.D. 2009) Scrutiny Committee made some observations regarding autonomous agencies (The Office of the Secretariat of the House of Representatives, 1998). It was said that the administrative costs and operating budget in some autonomous agencies is too high, especially salaries, personnel compensation, and renting expenditures. The Committee suggested that the government should review their missions, organizational structures, and formulate measures for efficient spending and control. In addition, the government should abolish autonomous agencies that fail to pass the evaluation or have duplicated functions with other agencies. Careful consideration needs to be given before any new autonomous agency can be set up.

5.3.5.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

Service process improvement is an obvious example of successful performance management reform in the public sector. Examples include e-revenue, e-car license, and e-identification card. In the past,

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

104 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

people had to spend the entire day paying taxes or renewing their car licenses, and they had to wait 3 months before getting their ID cards. With the process improvement, people can now pay taxes online, drive in to get a car license, and spend only 10 minutes getting ID cards. These successes are reflected in terms of simple and shortened procedures for service delivery and time reduction. Such process improvement applies process-oriented concepts and information technology for implementation.

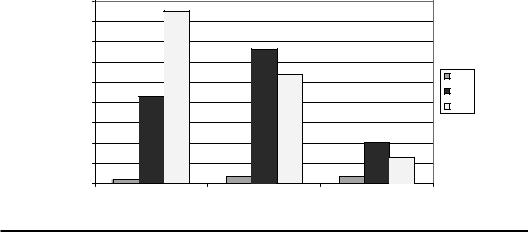

OPDC monitored the progress of process improvement during 2003–2005. Figure 5.2 shows the number of work processes during 2003–2005 and the percentage of time reduction in the various government agencies. The work processes, which reduced time by more than 50%, increased every year, from 2003–2005. There were 184 processes that reduced time by 50% in 2003, 4281 processes in 2004, and 8491 processes in 2005 (OPDC, 2006).

Despite the impressive numbers shown by the OPDC, there are some issues that need to be considered for quality improvement, i.e., the appropriateness of the guiding approach in using information technology, the objectives of the policy, and the readiness of the country. From an earlier study, it was found that the technical approach, emphasizing physical technology and system capabilities rather than the contexts surrounding the technology, plays an important role in guiding e-government projects (Lorsuwannarat, 2006). During the Thaksin government, many e-government projects were influenced by modern technology rather than the real needs of the people. Information technology is seen as a panacea to help increase efficiency, transparency, anticorruption, and good governance in the public sector. Many other factors were neglected, such as culture, behavior, social structure, economy, and politics.

For example, e-auction is a procurement process using web-based software that allows suppliers to bid online for a contract to supply goods and services. It aims to prevent collusion. However, in practice, collusion is possible even before e-auction starts its course. At present, there are only a few people who use computers in Tambol districts. The smart card aims to be a multi-application ID card that uses the 13 digit ID to link with other databases. In reality, people can only use a smart card as a single application like a normal ID card, since it cannot link with other databases at the moment. Furthermore, the Thaksin government wanted to use information technology to provide services to people in every area of central, regional, and local government services before

Number of Work Processes

9000 |

8,491 |

|

|

|

|

||

8000 |

|

6,637 |

|

7000 |

|

||

|

|

||

6000 |

|

5,392 |

|

5000 |

4,281 |

2003 |

|

2004 |

|||

|

|||

4000 |

|

||

|

2005 |

||

|

|

||

3000 |

|

2,026 |

|

2000 |

|

||

|

1,289 |

||

|

|

||

1000 |

307 |

312 |

|

184 |

|||

0 |

|

|

More than 50% |

30-50% |

Less than 30% |

|

Percentage of Time Reduction |

|

Figure 5.2 Summary of implementation on work process and time reduction during 2003– 2005. Source: Office of the Public Sector Development Commission, Annual Report 2006, p.98, on www.opdc.go.th.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Performance Management Reforms in Thailand 105

2010. This objective was quite idealistic since only 9.56% of Thailand’s population has access to the internet (portal.unesco.org). This compares to other developed countries, such as South Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Finland, Sweden, Canada, and the United States, which have very high internet accessibility of approximately 50%–60% of the population (Lorsuwannarat, 2006).

5.3.5.3 Knowledge Management

The strength of using laws and regulations made knowledge management diffuse rapidly in the Thai public sector. Many government agencies use community of practice (COP) techniques to share and distribute knowledge inside their organizations. Some use information technology to be the network for knowledge sharing in the organizations. Implementing systematic knowledge management helps government agencies to gain higher scores for their performance evaluation. The number of agencies that implement knowledge management is increasing (from 46.8% in 2001–2005 to 76% in 2006), but only 34.3% of implementers fully use knowledge management, whereas 41.1% of implementers use it with limitations (Lorsuwannarat, 2007b). One explanation may be because the concept of knowledge management is rather abstract and there are no specific guidelines for implementation. The success of knowledge management depends on the understanding of the agencies and the vision of their leaders.

5.3.5.4 Performance Agreement

At present, most public sector organizations have used the Performance Agreement to evaluate their performance and have submitted the results in the form of SAR reports to the OPDC three times a year. This performance agreement is a systematic evaluation form that can assist the agencies not only to monitor and evaluate, but also to improve their performance.

Nonetheless, there are some limitations concerning the Performance Agreement. These include choosing the appropriate measurement to evaluate the performance of every agency, creating the culture supporting performance evaluation, and building the systems as well as the mechanisms for performance evaluation. Each agency has different missions, objectives, and contexts. To find the right measurement for every agency, quantitatively and qualitatively, including inputs, procedures, outputs, and outcomes, is a challenging job for the OPDC. Without organizational culture supporting the performance evaluation, an agency will have difficulties in following the Performance Agreement. Another limitation of the Performance Agreement is the high frequency of sending SAR reports (three times a year), which increases the burden of the agencies, especially for universities that are evaluated by the Commission of Higher Education and the Office for Standards in Education concerning their education quality. The universities still need to prepare performance agreements for the OPDC, instead of simply using the reports submitted to the two central education agencies. This limitation highlights the duplication of the structures and functions of the central evaluation agencies. As a result, the reporting agencies have to spend more time and effort in preparing the data and reports.

5.4Recent Efforts at Budgeting Reform: A Move Toward Performance-based Budgeting

Previously, Thailand’s budget system had been highly centralized and based on line-item input budgeting. Government agencies requested budgets from the Bureau of the Budget in numerous

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

106 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

detailed budget lines. The budgets were approved on a very detailed level and were subject to further central input clearance when the agencies sought to spend the funds. While this centralization ensured overall fiscal discipline, it imposed inflexibility. And with this extensive input control, there was no incentive for the government agencies to increase the performance of their budgets.

As part of the Public Sector Performance Management Reform Program, in early 1999, Thailand launched a budget reform that would improve budget management and promote better flexibility and performance. The objective of budget reform in Thailand was to reorient the budget toward a greater focus on performance and result. At the same time, efforts were made to reduce input and other central control and to empower spending agencies to take on more responsibility for their own activities.

5.4.1 Control-Orientation Budgeting in Thailand

Thailand has had an excellent record of budget control. Public debt in Thailand has been quite low by international standards. Prior to the economic crisis in 1997 (especially from 1991 to 1996), the level of total public debt was only 20.08% of GDP on average. Following the 1997 economic crisis, public debt increased to more than 50% of GDP owing to the increase in public debt from government budget deficit and the debt assumed by the government in connection with the bailout of the distressed financial institutions following the economic crisis. Thailand’s public debt peaked at 58.9% of GDP in 2002. Since then the government has been able to commit itself to running a balanced budget, which has caused the debt ratio to decline to 50.6% in 2004, 41.3% in 2006, 37.8% in 2007, and 39.9% in early 2009 (Public Debt Management Office, 2009).

This excellent record of budget control was facilitated in part by a centralized budgeting process based on line-item input budgeting (Blondal & Kim, 2006: 10). This detailed control helped Thailand avoid overspending, but it was also costly, undermining flexibility and the quality of agency spending.

During the agency budget preparation phase, line ministries and departments usually played a limited role in analyzing the policies and impacts of the budgets. The activities surrounding budget preparation focused mainly on figures and numbers to ensure that they were correct and within the budget ceiling. This over-attention to line-item details came at the expense of attention to larger policy and performance issues (Mokoro Ltd., 1999: 21).

During the budget approval period, Parliament did not have adequate information on budget policies or impacts. The line-item information provided in the budget documents fostered micromanagement questions over details from Parliament. Information such as rationales for budget priorities, the development and fiscal impacts of budget policies, the performance of work plans and projects etc., were mainly absent during parliamentary budget approval (McCleary & Sakol, 1999: 11; Mokoro Ltd., 1999: 36).

During budget execution, budget allocations were made in numerous small lines. T he Comptroller-General’s Department replenished agency accounts on a detailed transaction-by- transaction basis. As a result, there was little flexibility within the appropriation structure for managers to redeploy funds to accommodate changing circumstances (World Bank, 2000: 58). In this rule-driven environment, managers had little flexibility or incentive to develop the budgeting capacity to allocate funds more effectively or to deliver outputs using fewer resources.

5.4.2Thailand’s Budget Reform Strategy: An Effort to Increase Flexibility and Reinforce Financial Performance

The core objective of budget reform in Thailand in early 1999 was to reduce centralized budget control by granting spending agencies more flexibility in their spending while trying to increase

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Performance Management Reforms in Thailand 107

the competencies of the agencies’ financial and performance management. This granting of flexibility in exchange for enhanced performance was termed the “hurdle” approach to budget reform (Bureau of the Budget, 1999).

In 1999, the Bureau of the Budget agreed to ease detailed central control over spending agencies by reducing some line-item details in their budget allocations and moving toward block grants on condition that the spending agencies were able to pass seven hurdle standards. These standards involved: budget planning, output costing, procurement management, budget and fund control, financial and performance reporting, asset management, and internal auditing (Bureau of the Budget, 1999: 5). All these criteria cover the core financial and performance management competencies that a line agency needs to enhance in exchange for a reduction in external controls. External controls could then be reduced with less risk of wasted resources and greater chance of attaining better performance and outcome from government spending (Bureau of the Budget, 1999: 6).

This performance-based budgeting reform was piloted. In the fiscal year 2000, pilots were underway in six ministries: the Ministry of Education (Office of the National Primary Education Commission, Department of General Education), the Ministry of University Affairs (Chulalongkorn University), the Ministry of Public Health (Provincial Hospital Division), the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Office of the Civil Service Commission (Bureau of the Budget, 1999: 5).

Each pilot agency would sign a resource agreement with the Bureau of the Budget. For each pilot agency, the resource agreement would formalize the increased flexibility in budget funding, a medium-term expenditure framework, financial control standards, and performance reporting standards. Prior to signing a resource agreement, two steps were required from each pilot agency:

(1) identification of gaps in its financial control and performance reporting systems, and (2) successful implementation of gap-filling actions. The timing of the resource agreement would depend on the scale of the gap filling required and the intensity of the gap-filling effort. This procedure was intended to provide spending agencies with more flexibility without compromising the standards of financial control and performance (Bureau of the Budget, 1999: 7).

5.4.3 Move Toward Strategic Performance-based Budgeting

Under the hurdle approach, the Bureau of the Budget would ease its controls over spending agencies only if the agencies were able to achieve the hurdle standards, which meant that central control was reduced only on an agency-by- agency basis. Therefore, this approach would increase the risk of stalled budget reform if agencies took a long time to achieve the hurdle standards.

Slow progress was actually the problem in Thailand because the hurdle standards were set at such a high level that hardly any organization could fulfill them. There was much confusion in the pilot agencies over what was required to achieve the hurdle standards (World Bank, 2002: 3; Blondal & Kim, 2006: 10–11). As observed by the World Bank (2002: 3), “in 2001 the Bureau of the Budget eased central controls on the six pilot agencies by reducing some line item details in the budget allocations, moving toward block grants. Only in 2002 has the number of pilot agencies been increased beyond the original six. Progress did not proceed entirely according to the textbook. The first steps toward block grants tended to precede improvements in financial management – creating a need for further post-devolution upgrading of financial management in most pilot agencies.”

The Thai government, dissatisfied with the pace of progress, decided that all ministries and agencies (not just pioneers) would move to the new performance-based budgeting system—which was now termed the “Strategic Performance-Based Budget” (SPBB). This became effective in fiscal year 2003.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC