- •Public Administration And Public Policy

- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •About The Authors

- •Comments On Purpose and Methods

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Culture

- •1.3 Colonial Legacies

- •1.3.1 British Colonial Legacy

- •1.3.2 Latin Legacy

- •1.3.3 American Legacy

- •1.4 Decentralization

- •1.5 Ethics

- •1.5.1 Types of Corruption

- •1.5.2 Ethics Management

- •1.6 Performance Management

- •1.6.2 Structural Changes

- •1.6.3 New Public Management

- •1.7 Civil Service

- •1.7.1 Size

- •1.7.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •1.7.3 Pay and Performance

- •1.7.4 Training

- •1.8 Conclusion

- •Contents

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Historical Developments and Legacies

- •2.2.1.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of King as Leader

- •2.2.1.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.1.3 Third Legacy: Traditions of Hierarchy and Clientelism

- •2.2.1.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition of Reconciliation

- •2.2.2.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of Bureaucratic Elites as a Privileged Group

- •2.2.2.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.2.3 Third Legacy: The Practice of Staging Military Coups

- •2.2.2.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition for Military Elites to be Loyal to the King

- •2.2.3.1 First Legacy: Elected Politicians as the New Political Boss

- •2.2.3.2 Second Legacy: Frequent and Unpredictable Changes of Political Bosses

- •2.2.3.3 Third Legacy: Politicians from the Provinces Becoming Bosses

- •2.2.3.4 Fourth Legacy: The Problem with the Credibility of Politicians

- •2.2.4.1 First Emerging Legacy: Big Businessmen in Power

- •2.2.4.2 Second Emerging Legacy: Super CEO Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.4.3 Third Emerging Legacy: Government must Serve Big Business Interests

- •2.2.5.1 Emerging Legacy: The Clash between Governance Values and Thai Realities

- •2.2.5.2 Traits of Governmental Culture Produced by the Five Masters

- •2.3 Uniqueness of the Thai Political Context

- •2.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •3.1 Thailand Administrative Structure

- •3.2 History of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.2.1 Thailand as a Centralized State

- •3.2.2 Towards Decentralization

- •3.3 The Politics of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.3.2 Shrinking Political Power of the Military and Bureaucracy

- •3.4 Drafting the TAO Law 199421

- •3.5 Impacts of the Decentralization Reform on Local Government in Thailand: Ongoing Challenges

- •3.5.1 Strong Executive System

- •3.5.2 Thai Local Political System

- •3.5.3 Fiscal Decentralization

- •3.5.4 Transferred Responsibilities

- •3.5.5 Limited Spending on Personnel

- •3.5.6 New Local Government Personnel System

- •3.6 Local Governments Reaching Out to Local Community

- •3.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Corruption: General Situation in Thailand

- •4.2.1 Transparency International and its Corruption Perception Index

- •4.2.2 Types of Corruption

- •4.3 A Deeper Look at Corruption in Thailand

- •4.3.1 Vanishing Moral Lessons

- •4.3.4 High Premium on Political Stability

- •4.4 Existing State Mechanisms to Fight Corruption

- •4.4.2 Constraints and Limitations of Public Agencies

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 History of Performance Management

- •5.2.1 National Economic and Social Development Plans

- •5.2.2 Master Plan of Government Administrative Reform

- •5.3 Performance Management Reform: A Move Toward High Performance Organizations

- •5.3.1 Organization Restructuring to Increase Autonomy

- •5.3.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.3 Knowledge Management Toward Learning Organizations

- •5.3.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.3.5 Challenges and Lessons Learned

- •5.3.5.1 Organizational Restructuring

- •5.3.5.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.5.3 Knowledge Management

- •5.3.5.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.4.4 Outcome of Budgeting Reform: The Budget Process in Thailand

- •5.4.5 Conclusion

- •5.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •6.1.1 Civil Service Personnel

- •6.1.2 Development of the Civil Service Human Resource System

- •6.1.3 Problems of Civil Service Human Resource

- •6.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •6.2.1 Main Feature

- •6.2.2 Challenges of Recruitment and Selection

- •6.3.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.2 Salary Management

- •6.4.2.2 Performance Management and Salary Increase

- •6.4.3 Position Allowance

- •6.4.5 National Compensation Committee

- •6.4.6 Retirement and Pension

- •6.4.7 Challenges in Compensation

- •6.5 Training and Development

- •6.5.1 Main Feature

- •6.5.2 Challenges of Training and Development in the Civil Service

- •6.6 Discipline and Merit Protection

- •6.6.1 Main Feature

- •6.6.2 Challenges of Discipline

- •6.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •English References

- •Contents

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Setting and Context

- •7.3 Malayan Union and the Birth of the United Malays National Organization

- •7.4 Post Independence, New Economic Policy, and Malay Dominance

- •7.5 Centralization of Executive Powers under Mahathir

- •7.6 Administrative Values

- •7.6.1 Close Ties with the Political Party

- •7.6.2 Laws that Promote Secrecy, Continuing Concerns with Corruption

- •7.6.3 Politics over Performance

- •7.6.4 Increasing Islamization of the Civil Service

- •7.7 Ethnic Politics and Reforms

- •7.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 System of Government in Malaysia

- •8.5 Community Relations and Emerging Recentralization

- •8.6 Process Toward Recentralization and Weakening Decentralization

- •8.7 Reinforcing Centralization

- •8.8 Restructuring and Impact on Decentralization

- •8.9 Where to Decentralization?

- •8.10 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia: General Observations

- •9.2.1 Factors of Corruption

- •9.3 Recent Corruption Scandals

- •9.3.1 Cases Involving Bureaucrats and Executives

- •9.3.2 Procurement Issues

- •9.4 Efforts to Address Corruption and Instill Ethics

- •9.4.1.1 Educational Strategy

- •9.4.1.2 Preventive Strategy

- •9.4.1.3 Punitive Strategy

- •9.4.2 Public Accounts Committee and Public Complaints Bureau

- •9.5 Other Efforts

- •9.6 Assessment and Recommendations

- •9.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •10.1 History of Performance Management in the Administrative System

- •10.1.1 Policy Frameworks

- •10.1.2 Organizational Structures

- •10.1.2.1 Values and Work Ethic

- •10.1.2.2 Administrative Devices

- •10.1.2.3 Performance, Financial, and Budgetary Reporting

- •10.2 Performance Management Reforms in the Past Ten Years

- •10.2.1 Electronic Government

- •10.2.2 Public Service Delivery System

- •10.2.3 Other Management Reforms

- •10.3 Assessment of Performance Management Reforms

- •10.4 Analysis and Recommendations

- •10.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.2.1 Public Service Department

- •11.2.2 Public Service Commission

- •11.2.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •11.2.4 Malaysian Administrative Modernization and Management Planning Unit

- •11.2.5 Administrative and Diplomatic Service

- •11.4 Civil Service Pension Scheme

- •11.5 Civil Service Neutrality

- •11.6 Civil Service Culture

- •11.7 Reform in the Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.2.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.3.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.3.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.4.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.4.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.5.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.5.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.6.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.6.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.7 Public Administration and Society

- •12.7.1 Public Accountability and Participation

- •12.7.2 Administrative Values

- •12.8 Societal and Political Challenge over Bureaucratic Dominance

- •12.9 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.3 Constitutional Framework of the Basic Law

- •13.4 Changing Relations between the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •13.4.1 Constitutional Dimension

- •13.4.1.1 Contending Interpretations over the Basic Law

- •13.4.1.3 New Constitutional Order in the Making

- •13.4.2 Political Dimension

- •13.4.2.3 Contention over Political Reform

- •13.4.3 The Economic Dimension

- •13.4.3.1 Expanding Intergovernmental Links

- •13.4.3.2 Fostering Closer Economic Partnership and Financial Relations

- •13.4.3.3 Seeking Cooperation and Coordination in Regional and National Development

- •13.4.4 External Dimension

- •13.5 Challenges and Prospects in the Relations between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •References

- •Contents

- •14.1 Honesty, Integrity, and Adherence to the Law

- •14.2 Accountability, Openness, and Political Neutrality

- •14.2.1 Accountability

- •14.2.2 Openness

- •14.2.3 Political Neutrality

- •14.3 Impartiality and Service to the Community

- •14.4 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Brief Overview of Performance Management in Hong Kong

- •15.3.1 Measuring and Assessing Performance

- •15.3.2 Adoption of Performance Pledges

- •15.3.3 Linking Budget to Performance

- •15.3.4 Relating Rewards to Performance

- •15.4 Assessment of Outcomes of Performance Management Reforms

- •15.4.1 Are Departments Properly Measuring their Performance?

- •15.4.2 Are Budget Decisions Based on Performance Results?

- •15.4.5 Overall Evaluation

- •15.5 Measurability of Performance

- •15.6 Ownership of, and Responsibility for, Performance

- •15.7 The Politics of Performance

- •15.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Structure of the Public Sector

- •16.2.1 Core Government

- •16.2.2 Hybrid Agencies

- •16.2.4 Private Businesses that Deliver Public Services

- •16.3 Administrative Values

- •16.4 Politicians and Bureaucrats

- •16.5 Management Tools and their Reform

- •16.5.1 Selection

- •16.5.2 Performance Management

- •16.5.3 Compensation

- •16.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 The Philippines: A Brief Background

- •17.4 Philippine Bureaucracy during the Spanish Colonial Regime

- •17.6 American Colonial Regime and the Philippine Commonwealth

- •17.8 Independence Period and the Establishment of the Institute of Public Administration

- •17.9 Administrative Values in the Philippines

- •17.11 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Toward a Genuine Local Autonomy and Decentralization in the Philippines

- •18.2.1 Evolution of Local Autonomy

- •18.2.2 Government Structure and the Local Government System

- •18.2.3 Devolution under the Local Government Code of 1991

- •18.2.4 Local Government Finance

- •18.2.5 Local Government Bureaucracy and Personnel

- •18.3 Review of the Local Government Code of 1991 and its Implementation

- •18.3.1 Gains and Successes of Decentralization

- •18.3.2 Assessing the Impact of Decentralization

- •18.3.2.1 Overall Policy Design

- •18.3.2.2 Administrative and Political Issues

- •18.3.2.2.1 Central and Sub-National Role in Devolution

- •18.3.2.2.3 High Budget for Personnel at the Local Level

- •18.3.2.2.4 Political Capture by the Elite

- •18.3.2.3 Fiscal Decentralization Issues

- •18.3.2.3.1 Macroeconomic Stability

- •18.3.2.3.2 Policy Design Issues of the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.3.2.3.4 Disruptive Effect of the Creation of New Local Government Units

- •18.3.2.3.5 Disparate Planning, Unhealthy Competition, and Corruption

- •18.4 Local Governance Reforms, Capacity Building, and Research Agenda

- •18.4.1 Financial Resources and Reforming the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.4.3 Government Functions and Powers

- •18.4.6 Local Government Performance Measurement

- •18.4.7 Capacity Building

- •18.4.8 People Participation

- •18.4.9 Political Concerns

- •18.4.10 Federalism

- •18.5 Conclusions and the Way Forward

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Control

- •19.2.1 Laws that Break Up the Alignment of Forces to Minimize State Capture

- •19.2.2 Executive Measures that Optimize Deterrence

- •19.2.3 Initiatives that Close Regulatory Gaps

- •19.2.4 Collateral Measures on Electoral Reform

- •19.3 Guidance

- •19.3.1 Leadership that Casts a Wide Net over Corrupt Acts

- •19.3.2 Limiting Monopoly and Discretion to Constrain Abuse of Power

- •19.3.3 Participatory Appraisal that Increases Agency Resistance against Misconduct

- •19.3.4 Steps that Encourage Public Vigilance and the Growth of Civil Society Watchdogs

- •19.3.5 Decentralized Guidance that eases Log Jams in Centralized Decision Making

- •19.4 Management

- •19.5 Creating Virtuous Circles in Public Ethics and Accountability

- •19.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today

- •20.3 Past Reform Initiatives of the Philippine Public Administrative System

- •20.4.1 Rebuilding Institutions and Improving Performance

- •20.4.1.1 Size and Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.1.2 Privatization

- •20.4.1.3 Addressing Corruption

- •20.4.1.5 Improving Work Processes

- •20.4.2 Performance Management Initiatives for the New Millennium

- •20.4.2.1 Financial Management

- •20.4.2.2 New Government Accounting System

- •20.4.2.3 Public Expenditure Management

- •20.4.2.4 Procurement Reforms

- •20.4.3 Human Resource Management

- •20.4.3.1 Organizing for Performance

- •20.4.3.2 Performance Evaluation

- •20.4.3.3 Rationalizing the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.3.4 Public Sector Compensation

- •20.4.3.5 Quality Management Systems

- •20.4.3.6 Local Government Initiatives

- •20.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Country Development Context

- •21.3 Evolution and Current State of the Philippine Civil Service System

- •21.3.1 Beginnings of a Modern Civil Service

- •21.3.2 Inventory of Government Personnel

- •21.3.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •21.3.6 Training and Development

- •21.3.7 Incentive Structure in the Bureaucracy

- •21.3.8 Filipino Culture

- •21.3.9 Bureaucratic Values and Performance Culture

- •21.3.10 Grievance and Redress System

- •21.4 Development Performance of the Philippine Civil Service

- •21.5 Key Development Challenges

- •21.5.1 Corruption

- •21.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 History

- •22.3 Major Reform Measures since the Handover

- •22.4 Analysis of the Reform Roadmap

- •22.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •23.1 Decentralization, Autonomy, and Democracy

- •23.3.1 From Recession to Take Off

- •23.3.2 Politics of Growth

- •23.3.3 Government Inertia

- •23.4 Autonomy as Collective Identity

- •23.4.3 Social Group Dynamics

- •23.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Functions and Performance of the Commission Against Corruption of Macao

- •24.2.1 Functions

- •24.2.2 Guidelines on the Professional Ethics and Conduct of Public Servants

- •24.2.3 Performance

- •24.2.4 Structure

- •24.2.5 Personnel Establishment

- •24.3 New Challenges

- •24.3.1 The Case of Ao Man Long

- •24.3.2 Dilemma of Sunshine Law

- •24.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Theoretical Basis of the Reform

- •25.3 Historical Background

- •25.4 Problems in the Civil Service Culture

- •25.5 Systemic Problems

- •25.6 Performance Management Reform

- •25.6.1 Performance Pledges

- •25.6.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.7 Results and Problems

- •25.7.1 Performance Pledge

- •25.7.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.8 Conclusion and Future Development

- •References

- •Contents

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Civil Service System

- •26.2.1 Types of Civil Servants

- •26.2.2 Bureaucratic Structure

- •26.2.4 Personnel Management

- •26.4 Civil Service Reform

- •26.5 Conclusion

- •References

436 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

Table 21.6 Salary Grades of Key Government Officials

Position |

SG |

|

|

President |

33 |

|

|

Vice-president |

32 |

|

|

President of the Senate |

32 |

|

|

Speaker of the House of Representatives |

32 |

|

|

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court |

32 |

|

|

Senator |

31 |

|

|

Member of the House of Representatives |

31 |

|

|

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court |

31 |

|

|

Chairman, Constitutional Commission |

31 |

|

|

Commissioner, Constitutional Commission |

30 |

|

|

Source: RA 6758 – Revised Compensation and Classification System (1984).

21.3.6 Training and Development

Decentralized human resource management and development is the guiding principle of the civil service in the Philippines. To achieve this goal, the CSC issued Memorandum Circular (MC) No. 20 (1990) granting agencies authority to approve their own training and development plans. The program complemented MC No. 20 by conducting a training needs inventory in 1464 agencies. It also launched a mechanism for monitoring and evaluation of training programs called Program for Evaluation of Resources Maximization in Training (PERMIT) and conducted a seminar on government employee relations, leadership and organizing techniques through the Advanced Leadership and Employee Relations Training (ALERT) Program.

Other programs initiated by the CSC in the area of human resource development are Field Officers Legal Appreciation Seminar on Higher Results and Efficiency (FLASH), Program for Legal Experts Advancement (PLEA), and Work Improvement Schemes Effectiveness (WISE). In addition, it also extended scholarships to qualified government personnel and established a Personnel Development Committee (PDC) in government offices. The programs initiated by the government allowed civil servants to become more flexible for future tasks. The training programs also serve as an avenue for employees to share their experiences and provide vital contributions in further strengthening the civil service in the Philippines.

The CSC sponsors the Local Scholarship Program (LSP), which aims to provide educational opportunities, particularly in pursuing graduate studies, to qualified government employees in preparation for higher responsibilities. It seeks to enhance the knowledge, skills, attitude toward career, and personal growth and advancement (CSC 2010). Box 21.2 indicates the various components of the LSP. Table 21.8 indicates the number of beneficiaries and graduates of the LSP from 1993 to 2002.

Many of the scholarship programs are tied to the official development assistance (ODA) of donor countries like the United States, Japan, Australia, and the European Union, among others. Civil servants are allowed to pursue a degree program while retaining their positions and

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Civil Service System in the Philippines 437

Table 21.7 Top and Bottom Five SG Levels

Salary Grade |

Monthly rate (in Php) |

No. of Positions |

|

|

|

33 |

57,750 |

1 |

|

|

|

32 |

46,200–54,917 |

4 |

|

|

|

31 |

40,425–48,052 |

355 |

|

|

|

30 |

28,875–34,323 |

412 |

|

|

|

29 |

25,333–30,113 |

2,999 |

|

|

|

5 |

7,043–8,375 |

10,765 |

|

|

|

4 |

6,522–7,751 |

32,198 |

|

|

|

3 |

6,039–7,177 |

21,635 |

|

|

|

2 |

5,540–6,585 |

6,764 |

|

|

|

1 |

5,082–6,041 |

23,677 |

|

|

|

Source: DBM (2005).

compensation on condition of returning to the service. With the above-mentioned programs, training in the civil service is supply driven. It is usually tied to the ODA or a meager training fund in the government budget. Owing to the limited fiscal space of the government over the past years, training receives the least priority.

Among the organizations involved in the conduct of training for civil servants are the Office of the Personnel Development and Services (OPDS) and the CESB for CES officers under the CSC; academic institutions like the National College of Public Administration and Governance of the University of the Philippines, the Development Academy of the Philippine (DAP), and the Local Government Academy (LGA) of the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG).

BOX 21.2 COMPONENT OF THE LOCAL SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

The components of the Local Scholarship Program are: (1) LSP-Masteral Degree (LSP-MD), which was established in 1993 through CSC Resolution No. 93-299 to provide qualified government employees with a 1-year scholarship grant to pursue masteral or post graduate studies; (2) LSP-Bachelor’s Degree Completion (LSP-BDC), started in 1996 by virtue of CSC Resolution No. 967300, which offers undergraduates in government a 2-year scholarship to complete their studies and earn a college diploma; and (3) LSP-Skilled Workers in Government (LSP-SWG), instituted in 1994 under CSC Resolution No. 94-2380, which offers a short term (not exceeding 6 months), continuing skills upgrading or enhancement training to first level government employees holding clerical, trades, crafts, and custodial service positions.

Source: CSC website at www.csc.gov.ph/cscweb/scholarship.html.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

438 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

Table 21.8 LSP Beneficiaries and Graduates, 2002

Program |

No. of Beneficiaries |

No. of Graduates |

|

|

|

LSP-MD |

4,622 |

2,352 |

|

|

|

LSP-BDC |

701 |

397 |

|

|

|

LSP-SWG |

6,121 |

6,121 |

|

|

|

Total |

11,444 |

8,870 |

|

|

|

Source: CSC (2010).

Note: LSP-SWG has been suspended since 2001.

21.3.7 Incentive Structure in the Bureaucracy

Philippine public sector organizations—with some exempt GOCC and GFI entities—do not offer competitive compensation packages and incentives, unlike in developed countries in the West and other countries in Asia like Japan, South Korea, and even the Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong in China. Career growth in the public sector is rather slow compared to the private sector. Some positions in the government are considered “dead-end” with no opportunities for promotion, salary increase, or professional development.

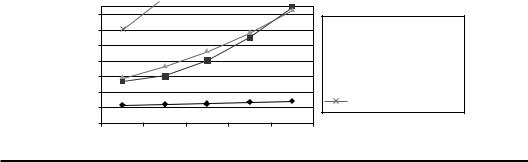

A study by the CSC in 2006 found that the salaries of third level or CES positions in the public sector are 74% lower, and professional and technical personnel are 40% lower compared to their counterparts in the private sector. The study used salaries of medium-sized business firms as a benchmark (PHDR 2008/2009). Figures 21.8, 21.9 and 21.10 show civil service officers not covered by the SSL, e.g., GFIs, have salaries that are comparable to those of managers in mediumsized private firms. However, the disparity or “inequity” becomes very wide for positions covered by the SLL at the CES and second levels, but there is not much difference in the salaries of first level civil servants with those in medium-sized private firms in the Philippines (CSC 2006).

21.3.8 Filipino Culture

It is important to appreciate the basic features of the Filipino culture; it would partly explain the way people think and respond to circumstances between the Philippine civil service and society.

140,000

120,000

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

0

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

SSL covered (ave expenditure per cap)

SSL covered (ave expenditure per cap)  SSL exempt (LBP)

SSL exempt (LBP)

Private: medium-sized firms

Private: medium-sized firms

Private: whole sample

Figure 21.8 Comparison of salaries: Higher technical, supervisory, and executive position (SG 25 and above). Source: Based on the CSC Compensation and Benefits Study from 2002–2006; Adapted from Monsod, T., HDN Discussion Paper Series, PHRD Issue 2008/2009, No. 4, 2009.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Civil Service System in the Philippines 439

140,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

120,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

80,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

60,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

40,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

12 |

14 |

16 |

19 |

22 |

24 |

10 |

SSL covered (ave expenditure per cap)

SSL covered (ave expenditure per cap)  SSL exempt (LBP)

SSL exempt (LBP)

Private: medium-sized firms

Private: medium-sized firms

Private: whole sample

Private: whole sample

Figure 21.9 Comparative of salaries: sub-professional and professional/technical positions (SG 10-24). Source: Based on the CSC Compensation and Benefits Study from 2002–2006; Adapted from Monsod, T., HDN Discussion Paper Series, PHRD Issue 2008/2009, No. 4, 2009.

Generally, Filipino society is “collectivist, family-oriented, and personal-oriented.” Filipinos value their personal relationships above all else (Montiel 2002). They feel responsible and have emotional attachment to their family, kin, and close friends. Filipino culture is very unique and humane in nature. Annex 3 summarizes the apparent Filipino values, which have a great influence on their behavior and way of thinking. Evidently, these too have a significant effect or influence on public administration, policymaking processes, and public decisions.

21.3.9 Bureaucratic Values and Performance Culture

Generally, being a civil servant in the Philippines—career and non-career—does not translate into earning the highest respect in society. Aside from the low government salaries, they are oftentimes tainted by stereotypes of incompetence, political patronage, politicking, and elected officials are commonly branded as “traditional politicians.”

In a study on the early civil service system and Philippine administrative culture, Varela (1996) noted that the “practice of political partisanship and interference in public employment is ingrained in our administrative and political system.” Somehow, political recommendation for employment was a standard practice in the civil service then. Government employees felt their salaries would always lag behind counterparts in the private sector. They did not strive for high

140,000 |

|

|

|

|

120,000 |

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|

|

|

80,000 |

|

|

|

|

60,000 |

|

|

|

|

40,000 |

|

|

|

|

20,000 |

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2,3 |

4,5 |

6,7 |

8,9 |

SSL covered (ave expenditure per cap)

SSL covered (ave expenditure per cap)  SSL exempt (LBP)

SSL exempt (LBP)

Private: medium-sized firms

Private: medium-sized firms

Private: whole sample

Private: whole sample

Figure 21.10 Comparison of salaries: Clerical and trade (SG 1-9). Source: Based on the CSC Compensation and Benefits Study from 2002–2006; Adapted from Monsod, T., HDN Discussion Paper Series, PHRD Issue 2008/2009, No. 4, 2009.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

440 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

performance since excellence or outstanding performance in government was not accompanied by rewards like promotion and/or a salary increase (p. 34).8

Many observers believe that the low salary is one cause for poor individual public performance, a good alibi to engage in corrupt practices, and contributory to the government’s inability to hire and maintain the best workers in the civil service. Some perceive that personalistic values like hiya (shame), pakikisama (conformity), utang na loob (debt of gratitude), kumpare (padrino), pakakipagkapwa (human relations), and familial closeness of the Filipino culture “bring about organizational behaviors which may be considered negative and dysfunctional when viewed from the Weberian bureaucratic standards” (Varela 1996: 19).

Today, about 10,000 positions, including the CES, are subject to presidential prerogative— which has tended to deepen political patronage and undermine established CSC rules and qualification standards (PHDR 2008/2009: 19–24). Evidence indicates that the number of CES eligibles or officers holding career positions is declining; this means that either political appointments are increasing or CESOs are voluntarily leaving their posts (PHDN 2008/2009: 25).

On the other hand, the proliferation of graft and corruption in government has been attributed to collusion, personal favors, lack of moral hazard, low incentives in government service, and the inability to hold friends and family relations to account for their actions. The political institutions have likewise failed to elect leaders—with exceptions—who are responsible and accountable to the constituency. Political interference, political patronage, and governance issues are major stumbling blocks to government efficiency and effectiveness.

Over the years, qualification standards and performance measures have been put in place by the CSC. However, it remains difficult to measure the overall quality, effectiveness, and efficiency of the bureaucracy. For NGAs, the organizational performance indicator framework (OPIF) was established to provide a mechanism whereby programs and projects are ranked and funded in terms of their priority and relevance to the achievement of the desired outcomes. Two mechanisms for the review of government programs and projects have been established. One is the sector effectiveness and efficiency review (SEER), which is geared toward prioritization of broad sectoral programs. The other is the agency performance review (APR), which is concerned with measuring the extent to which the desired program results of specific government agencies have been accomplished. For LGUs, the Local Government Performance Measurement System (LGPMPS) was introduced as a self-assessment tool to measure local government performance.

Alongside these review mechanisms, the executive department of the government advocated and implemented reforms in the procurement system. A new government accounting and auditing system (nGAS) has likewise been put in place to supplant a 50-year-old system, thus modernizing the financial recording and reporting of the entire public sector.

Some observers view the performance culture of the Philippine bureaucracy as frustrating. They stereotype the Philippine government as “big, slow and bumbling” (Mangahas 1993). The public often complain of government “inefficiency and ineffectiveness” in processing government documentary requirements, filing of or paying for income and property taxes, applying for land titles, or receiving public services, among others.

8This account relates to the Philippine civil service experience between 1961 and 1987, before the major overhaul of the Philippine civil service system.

©2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC