- •Public Administration And Public Policy

- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •About The Authors

- •Comments On Purpose and Methods

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Culture

- •1.3 Colonial Legacies

- •1.3.1 British Colonial Legacy

- •1.3.2 Latin Legacy

- •1.3.3 American Legacy

- •1.4 Decentralization

- •1.5 Ethics

- •1.5.1 Types of Corruption

- •1.5.2 Ethics Management

- •1.6 Performance Management

- •1.6.2 Structural Changes

- •1.6.3 New Public Management

- •1.7 Civil Service

- •1.7.1 Size

- •1.7.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •1.7.3 Pay and Performance

- •1.7.4 Training

- •1.8 Conclusion

- •Contents

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Historical Developments and Legacies

- •2.2.1.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of King as Leader

- •2.2.1.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.1.3 Third Legacy: Traditions of Hierarchy and Clientelism

- •2.2.1.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition of Reconciliation

- •2.2.2.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of Bureaucratic Elites as a Privileged Group

- •2.2.2.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.2.3 Third Legacy: The Practice of Staging Military Coups

- •2.2.2.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition for Military Elites to be Loyal to the King

- •2.2.3.1 First Legacy: Elected Politicians as the New Political Boss

- •2.2.3.2 Second Legacy: Frequent and Unpredictable Changes of Political Bosses

- •2.2.3.3 Third Legacy: Politicians from the Provinces Becoming Bosses

- •2.2.3.4 Fourth Legacy: The Problem with the Credibility of Politicians

- •2.2.4.1 First Emerging Legacy: Big Businessmen in Power

- •2.2.4.2 Second Emerging Legacy: Super CEO Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.4.3 Third Emerging Legacy: Government must Serve Big Business Interests

- •2.2.5.1 Emerging Legacy: The Clash between Governance Values and Thai Realities

- •2.2.5.2 Traits of Governmental Culture Produced by the Five Masters

- •2.3 Uniqueness of the Thai Political Context

- •2.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •3.1 Thailand Administrative Structure

- •3.2 History of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.2.1 Thailand as a Centralized State

- •3.2.2 Towards Decentralization

- •3.3 The Politics of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.3.2 Shrinking Political Power of the Military and Bureaucracy

- •3.4 Drafting the TAO Law 199421

- •3.5 Impacts of the Decentralization Reform on Local Government in Thailand: Ongoing Challenges

- •3.5.1 Strong Executive System

- •3.5.2 Thai Local Political System

- •3.5.3 Fiscal Decentralization

- •3.5.4 Transferred Responsibilities

- •3.5.5 Limited Spending on Personnel

- •3.5.6 New Local Government Personnel System

- •3.6 Local Governments Reaching Out to Local Community

- •3.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Corruption: General Situation in Thailand

- •4.2.1 Transparency International and its Corruption Perception Index

- •4.2.2 Types of Corruption

- •4.3 A Deeper Look at Corruption in Thailand

- •4.3.1 Vanishing Moral Lessons

- •4.3.4 High Premium on Political Stability

- •4.4 Existing State Mechanisms to Fight Corruption

- •4.4.2 Constraints and Limitations of Public Agencies

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 History of Performance Management

- •5.2.1 National Economic and Social Development Plans

- •5.2.2 Master Plan of Government Administrative Reform

- •5.3 Performance Management Reform: A Move Toward High Performance Organizations

- •5.3.1 Organization Restructuring to Increase Autonomy

- •5.3.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.3 Knowledge Management Toward Learning Organizations

- •5.3.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.3.5 Challenges and Lessons Learned

- •5.3.5.1 Organizational Restructuring

- •5.3.5.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.5.3 Knowledge Management

- •5.3.5.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.4.4 Outcome of Budgeting Reform: The Budget Process in Thailand

- •5.4.5 Conclusion

- •5.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •6.1.1 Civil Service Personnel

- •6.1.2 Development of the Civil Service Human Resource System

- •6.1.3 Problems of Civil Service Human Resource

- •6.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •6.2.1 Main Feature

- •6.2.2 Challenges of Recruitment and Selection

- •6.3.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.2 Salary Management

- •6.4.2.2 Performance Management and Salary Increase

- •6.4.3 Position Allowance

- •6.4.5 National Compensation Committee

- •6.4.6 Retirement and Pension

- •6.4.7 Challenges in Compensation

- •6.5 Training and Development

- •6.5.1 Main Feature

- •6.5.2 Challenges of Training and Development in the Civil Service

- •6.6 Discipline and Merit Protection

- •6.6.1 Main Feature

- •6.6.2 Challenges of Discipline

- •6.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •English References

- •Contents

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Setting and Context

- •7.3 Malayan Union and the Birth of the United Malays National Organization

- •7.4 Post Independence, New Economic Policy, and Malay Dominance

- •7.5 Centralization of Executive Powers under Mahathir

- •7.6 Administrative Values

- •7.6.1 Close Ties with the Political Party

- •7.6.2 Laws that Promote Secrecy, Continuing Concerns with Corruption

- •7.6.3 Politics over Performance

- •7.6.4 Increasing Islamization of the Civil Service

- •7.7 Ethnic Politics and Reforms

- •7.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 System of Government in Malaysia

- •8.5 Community Relations and Emerging Recentralization

- •8.6 Process Toward Recentralization and Weakening Decentralization

- •8.7 Reinforcing Centralization

- •8.8 Restructuring and Impact on Decentralization

- •8.9 Where to Decentralization?

- •8.10 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia: General Observations

- •9.2.1 Factors of Corruption

- •9.3 Recent Corruption Scandals

- •9.3.1 Cases Involving Bureaucrats and Executives

- •9.3.2 Procurement Issues

- •9.4 Efforts to Address Corruption and Instill Ethics

- •9.4.1.1 Educational Strategy

- •9.4.1.2 Preventive Strategy

- •9.4.1.3 Punitive Strategy

- •9.4.2 Public Accounts Committee and Public Complaints Bureau

- •9.5 Other Efforts

- •9.6 Assessment and Recommendations

- •9.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •10.1 History of Performance Management in the Administrative System

- •10.1.1 Policy Frameworks

- •10.1.2 Organizational Structures

- •10.1.2.1 Values and Work Ethic

- •10.1.2.2 Administrative Devices

- •10.1.2.3 Performance, Financial, and Budgetary Reporting

- •10.2 Performance Management Reforms in the Past Ten Years

- •10.2.1 Electronic Government

- •10.2.2 Public Service Delivery System

- •10.2.3 Other Management Reforms

- •10.3 Assessment of Performance Management Reforms

- •10.4 Analysis and Recommendations

- •10.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.2.1 Public Service Department

- •11.2.2 Public Service Commission

- •11.2.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •11.2.4 Malaysian Administrative Modernization and Management Planning Unit

- •11.2.5 Administrative and Diplomatic Service

- •11.4 Civil Service Pension Scheme

- •11.5 Civil Service Neutrality

- •11.6 Civil Service Culture

- •11.7 Reform in the Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.2.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.3.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.3.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.4.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.4.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.5.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.5.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.6.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.6.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.7 Public Administration and Society

- •12.7.1 Public Accountability and Participation

- •12.7.2 Administrative Values

- •12.8 Societal and Political Challenge over Bureaucratic Dominance

- •12.9 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.3 Constitutional Framework of the Basic Law

- •13.4 Changing Relations between the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •13.4.1 Constitutional Dimension

- •13.4.1.1 Contending Interpretations over the Basic Law

- •13.4.1.3 New Constitutional Order in the Making

- •13.4.2 Political Dimension

- •13.4.2.3 Contention over Political Reform

- •13.4.3 The Economic Dimension

- •13.4.3.1 Expanding Intergovernmental Links

- •13.4.3.2 Fostering Closer Economic Partnership and Financial Relations

- •13.4.3.3 Seeking Cooperation and Coordination in Regional and National Development

- •13.4.4 External Dimension

- •13.5 Challenges and Prospects in the Relations between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •References

- •Contents

- •14.1 Honesty, Integrity, and Adherence to the Law

- •14.2 Accountability, Openness, and Political Neutrality

- •14.2.1 Accountability

- •14.2.2 Openness

- •14.2.3 Political Neutrality

- •14.3 Impartiality and Service to the Community

- •14.4 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Brief Overview of Performance Management in Hong Kong

- •15.3.1 Measuring and Assessing Performance

- •15.3.2 Adoption of Performance Pledges

- •15.3.3 Linking Budget to Performance

- •15.3.4 Relating Rewards to Performance

- •15.4 Assessment of Outcomes of Performance Management Reforms

- •15.4.1 Are Departments Properly Measuring their Performance?

- •15.4.2 Are Budget Decisions Based on Performance Results?

- •15.4.5 Overall Evaluation

- •15.5 Measurability of Performance

- •15.6 Ownership of, and Responsibility for, Performance

- •15.7 The Politics of Performance

- •15.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Structure of the Public Sector

- •16.2.1 Core Government

- •16.2.2 Hybrid Agencies

- •16.2.4 Private Businesses that Deliver Public Services

- •16.3 Administrative Values

- •16.4 Politicians and Bureaucrats

- •16.5 Management Tools and their Reform

- •16.5.1 Selection

- •16.5.2 Performance Management

- •16.5.3 Compensation

- •16.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 The Philippines: A Brief Background

- •17.4 Philippine Bureaucracy during the Spanish Colonial Regime

- •17.6 American Colonial Regime and the Philippine Commonwealth

- •17.8 Independence Period and the Establishment of the Institute of Public Administration

- •17.9 Administrative Values in the Philippines

- •17.11 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Toward a Genuine Local Autonomy and Decentralization in the Philippines

- •18.2.1 Evolution of Local Autonomy

- •18.2.2 Government Structure and the Local Government System

- •18.2.3 Devolution under the Local Government Code of 1991

- •18.2.4 Local Government Finance

- •18.2.5 Local Government Bureaucracy and Personnel

- •18.3 Review of the Local Government Code of 1991 and its Implementation

- •18.3.1 Gains and Successes of Decentralization

- •18.3.2 Assessing the Impact of Decentralization

- •18.3.2.1 Overall Policy Design

- •18.3.2.2 Administrative and Political Issues

- •18.3.2.2.1 Central and Sub-National Role in Devolution

- •18.3.2.2.3 High Budget for Personnel at the Local Level

- •18.3.2.2.4 Political Capture by the Elite

- •18.3.2.3 Fiscal Decentralization Issues

- •18.3.2.3.1 Macroeconomic Stability

- •18.3.2.3.2 Policy Design Issues of the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.3.2.3.4 Disruptive Effect of the Creation of New Local Government Units

- •18.3.2.3.5 Disparate Planning, Unhealthy Competition, and Corruption

- •18.4 Local Governance Reforms, Capacity Building, and Research Agenda

- •18.4.1 Financial Resources and Reforming the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.4.3 Government Functions and Powers

- •18.4.6 Local Government Performance Measurement

- •18.4.7 Capacity Building

- •18.4.8 People Participation

- •18.4.9 Political Concerns

- •18.4.10 Federalism

- •18.5 Conclusions and the Way Forward

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Control

- •19.2.1 Laws that Break Up the Alignment of Forces to Minimize State Capture

- •19.2.2 Executive Measures that Optimize Deterrence

- •19.2.3 Initiatives that Close Regulatory Gaps

- •19.2.4 Collateral Measures on Electoral Reform

- •19.3 Guidance

- •19.3.1 Leadership that Casts a Wide Net over Corrupt Acts

- •19.3.2 Limiting Monopoly and Discretion to Constrain Abuse of Power

- •19.3.3 Participatory Appraisal that Increases Agency Resistance against Misconduct

- •19.3.4 Steps that Encourage Public Vigilance and the Growth of Civil Society Watchdogs

- •19.3.5 Decentralized Guidance that eases Log Jams in Centralized Decision Making

- •19.4 Management

- •19.5 Creating Virtuous Circles in Public Ethics and Accountability

- •19.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today

- •20.3 Past Reform Initiatives of the Philippine Public Administrative System

- •20.4.1 Rebuilding Institutions and Improving Performance

- •20.4.1.1 Size and Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.1.2 Privatization

- •20.4.1.3 Addressing Corruption

- •20.4.1.5 Improving Work Processes

- •20.4.2 Performance Management Initiatives for the New Millennium

- •20.4.2.1 Financial Management

- •20.4.2.2 New Government Accounting System

- •20.4.2.3 Public Expenditure Management

- •20.4.2.4 Procurement Reforms

- •20.4.3 Human Resource Management

- •20.4.3.1 Organizing for Performance

- •20.4.3.2 Performance Evaluation

- •20.4.3.3 Rationalizing the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.3.4 Public Sector Compensation

- •20.4.3.5 Quality Management Systems

- •20.4.3.6 Local Government Initiatives

- •20.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Country Development Context

- •21.3 Evolution and Current State of the Philippine Civil Service System

- •21.3.1 Beginnings of a Modern Civil Service

- •21.3.2 Inventory of Government Personnel

- •21.3.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •21.3.6 Training and Development

- •21.3.7 Incentive Structure in the Bureaucracy

- •21.3.8 Filipino Culture

- •21.3.9 Bureaucratic Values and Performance Culture

- •21.3.10 Grievance and Redress System

- •21.4 Development Performance of the Philippine Civil Service

- •21.5 Key Development Challenges

- •21.5.1 Corruption

- •21.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 History

- •22.3 Major Reform Measures since the Handover

- •22.4 Analysis of the Reform Roadmap

- •22.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •23.1 Decentralization, Autonomy, and Democracy

- •23.3.1 From Recession to Take Off

- •23.3.2 Politics of Growth

- •23.3.3 Government Inertia

- •23.4 Autonomy as Collective Identity

- •23.4.3 Social Group Dynamics

- •23.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Functions and Performance of the Commission Against Corruption of Macao

- •24.2.1 Functions

- •24.2.2 Guidelines on the Professional Ethics and Conduct of Public Servants

- •24.2.3 Performance

- •24.2.4 Structure

- •24.2.5 Personnel Establishment

- •24.3 New Challenges

- •24.3.1 The Case of Ao Man Long

- •24.3.2 Dilemma of Sunshine Law

- •24.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Theoretical Basis of the Reform

- •25.3 Historical Background

- •25.4 Problems in the Civil Service Culture

- •25.5 Systemic Problems

- •25.6 Performance Management Reform

- •25.6.1 Performance Pledges

- •25.6.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.7 Results and Problems

- •25.7.1 Performance Pledge

- •25.7.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.8 Conclusion and Future Development

- •References

- •Contents

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Civil Service System

- •26.2.1 Types of Civil Servants

- •26.2.2 Bureaucratic Structure

- •26.2.4 Personnel Management

- •26.4 Civil Service Reform

- •26.5 Conclusion

- •References

424 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

21.1 Introduction

This chapter describes the Philippine public administration system in terms of its evolution, structure, appointments, employment patterns, and distribution, and, to the extent possible, discusses its development effectiveness. This chapter is organized as follows: (1) country background, (2) beginnings and current state of the Philippine civil service system, (3) development performance of the civil service bureaucracy, (4) key development challenges, and (5) conclusion and future directions.

21.2 Country Development Context

For most of the last 30 years, the development performance of the Philippines has been less satisfactory than many of its Asian neighbors. In the 1950s and 1960s, the country had one of the highest per capita gross domestic products in the Asian region—higher than that of the People’s Republic of China, Indonesia, and Thailand. The Philippines is now lagging behind. The 2008–2009 Global Competitiveness Report ranked the Philippines 71st out of 134 countries. Placed 82nd out of 118 countries in the 2008 Global Enabling Trade Index, the Philippines trailed behind its Association of Southeast Asian counterparts, such as Singapore that ranked second in the survey, Malaysia at 29th, Indonesia at 47th, and Thailand in 52nd place. The economic performance of the Philippines has been slow and erratic—characterized by spurts of growth followed by bust and stagnation.

The ADB 2007 Critical Development Constraints Study on the Philippines identifies the following critical factors that constrain growth: (i) tight fiscal situation; (ii) inadequate infrastructure, particularly in electricity and transport; (iii) weak investor confidence due to governance concerns; and (iv) inability to address market failures leading to a small and narrow industrial base (ADB 2007). It is viewed that easing these critical constraints can trigger a growth process conducive to alleviating poverty and reducing inequality in the country. Improving the system of public administration and governance will significantly improve the country’s development effectiveness.

21.3Evolution and Current State of the Philippine Civil Service System

21.3.1 Beginnings of a Modern Civil Service

The Philippine civil service system is often associated as having been patterned on that of the American civil service system. During the American colonization of the Philippines, a merit system in the government was institutionalized. Civil service positions required passing the civil service examination as compared to the feudal, subjective, and politicized practices under the Spanish regime.

Public Law No. 5, also known as Act for the Establishment and Maintenance of Our Efficient and Honest Civil Service in the Philippine Island, established the Philippine civil service system in 1900 by the Second Philippine Commission. It created the three-man Civil Service Board (CSB)—headed by a chairman, assisted by a secretary and a chief examiner—to determine examinations, set age limits, and classify positions in the executive branch and the city government of Manila. Although CSB was reorganized as the Bureau in 1905, its function remained limited to examinations and appointments (CSC 1977: 4–6).

The 1935 Philippine Constitution established the merit system as the basis for employment in the government. Succeeding years witnessed the expansion of the Bureau’s jurisdiction to include

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Civil Service System in the Philippines 425

the three branches of government: the national government (NG), local government, and government corporations. In 1936, an executive order (EO) increased the function of the Bureau to include authority over the removal, separation, and suspension of subordinate officers and employees in the civil service.

Republic Act (RA) No. 2260 of the Civil Service Law was enacted in 1959. As the first integral law on Philippine bureaucracy, it superseded the scattered administrative orders issued since 1900 pertaining to government personnel administration. It introduced personnel policies that to date remain the most salient features of the system—promotion based on a system of ranking positions, a performance appraisal system to improve employee performance, and a more participative approach to management and interaction with employees. It elevated the Bureau to a Commission whose head is given the rank of department secretary (CSC 1977).

RA No. 6040 of 1069 amended RA No. 2260, which decentralized certain civil service functions, particularly examinations, appointments, and administrative discipline. Right after the imposition of martial law in 1972, Presidential Decree No. 1 reiterated the decentralization of personnel functions and restructured the commission to make it more amenable to its quasilegislative and quasi-judicial functions. In 1975, Presidential Decree No. 807 (The Civil Service Decree of the Philippines) re-defined the role of the commission to become the central personnel agency of the government.

The 1987 Constitution provides the framework for the professionalization of the Philippine bureaucracy after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship. It mandates the Civil Service Commission (CSC) to administer the civil service and that it shall be directed by a chair and two commissioners. It covers all branches, instrumentalities, and agencies of the government, including govern- ment-owned and controlled corporations (GOCCs) with original charters.

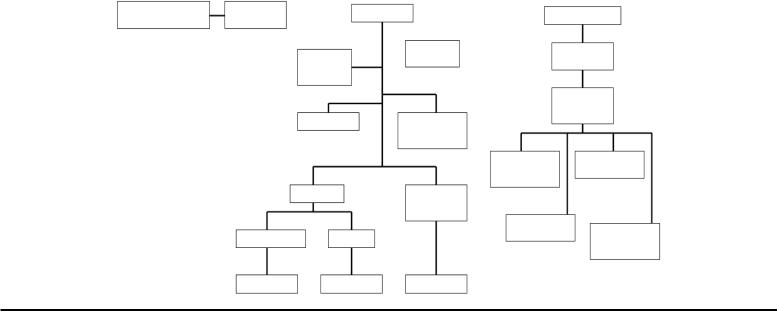

The Philippines is a democratic and republican state. It has a unitary form of government with a multi-tiered structure. There are three branches of government—the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary—that provide for separation of powers and a system of checks and balances. Figure 21.1 shows the structure of the government of the Philippines. An elected president heads the Executive branch. The upper and lower chambers of Congress—the Senate (with 24 senators elected nationally, for a 6-year term) and the House of Representatives (with more than 250 members elected by a legislative district and by party-list organizations)—comprise the Legislative Branch.2 The Supreme Court, headed by a chief justice, the Court of Appeals, regional trial courts, and other special courts comprise the Judicial Branch (ADB 2005b: 5–10).

Both the president and the vice president are elected nationally for a 6-year term. A president who has served a full term cannot be re-elected; the vice president cannot serve for more than two successive terms (The Omnibus Election Code of the Philippines 1992). The president has the power to (i) make executive decisions, (ii) veto laws passed by Congress, (iii) control the disbursement of NG funds, (iv) appoint secretaries and undersecretaries of the executive department, and (v) appoint justices and judges of the judicial branch (ADB 2005b: 5–10). The NG operates through about 20 departments, 28 other executive offices and services (OEOS) under the Office of the President, and 60 GOCCs including government financial institutions (GFIs) (DBM 2008).

The country is divided into 17 administrative regions and two autonomous regions, namely, the Cordillera Autonomous Region (CAR) and the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). Most government departments maintain regional offices. See Annex 1 for the administrative map of the Philippines. The local government units (LGUs) comprise the second tier of government—that

2Senators can serve for two consecutive terms while members of the House of Representatives, elected every 3 years, can serve for three consecutive terms.

©2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

LEGISLATIVE BRANCH |

|

EXECUTIVE BRANCH |

||

HOUSE OF |

SENATE |

PRESIDENT |

||

REPRESENTATIVES |

||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

NATIONAL |

VICE |

|

|

|

PRESIDENT |

||

|

|

SECURITY |

|

|

|

|

COUNCIL |

|

|

|

|

CABINET |

MAJOR |

|

|

|

|

COMMISSIONS |

|

|

|

|

AND OFFICES |

|

|

PROVINCES |

HIGHLY |

||

|

|

|

URBANIZED |

|

|

|

|

CITIES |

|

|

MUNICIPALITIES |

CITIES |

|

|

|

BARANGAYS |

BARANGAYS |

BARANGAYS |

|

JUDICIAL BRANCH

SUPREME COURT

COURT OF

APPEALS

REGIONAL

TRIAL

COURTS

MUNICIPAL |

METROPOLITAN |

TRIAL COURTS |

TRIAL COURTS |

IN CITIES |

|

MUNICIPAL

TRIAL COURTS MUNICIPAL CIRCUIT TRIAL

COURTS

Figure 21.1 Structure of the Philippine government. Source: U.S. Library of Congress, July 2006.

Asia Southeast in Administration Public 426

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Civil Service System in the Philippines 427

consists of three layers: provinces, component cities and municipalities, and villages or barangays. There are also independent or highly urbanized cities (HUCs) that are at the same level as provinces and are directly divided into barangays. Each level of LGU is headed by an elected official, i.e., provincial governor, city/municipal mayor, or barangay captain. Each level of LGU also has a legislative body consisting of an elected vice-governor or vice-mayor and council members (ADB 2005b: 5–10).

The enactment of RA 7160 or the Local Government Code (LGC) of 1991 has been considered a landmark, far-reaching, and the most radical piece of legislation in the history of the Philippine politico-administrative system. It devolved significant functions, powers, and respon- sibilities—and personnel—to the thousands of local governments in the country that have long been operating under a highly centralized regime: the delivery of basic services, authorized responsibility to enforce certain regulatory powers, increased financial resources to LGUs, legitimized participation for civil society in local governance, and authorized entrepreneurial and development activities by LGUs (Brillantes 2003a, 2003b).

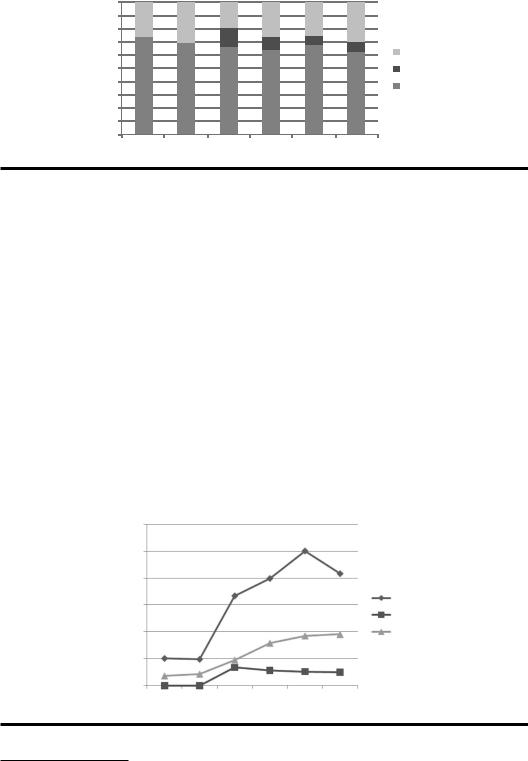

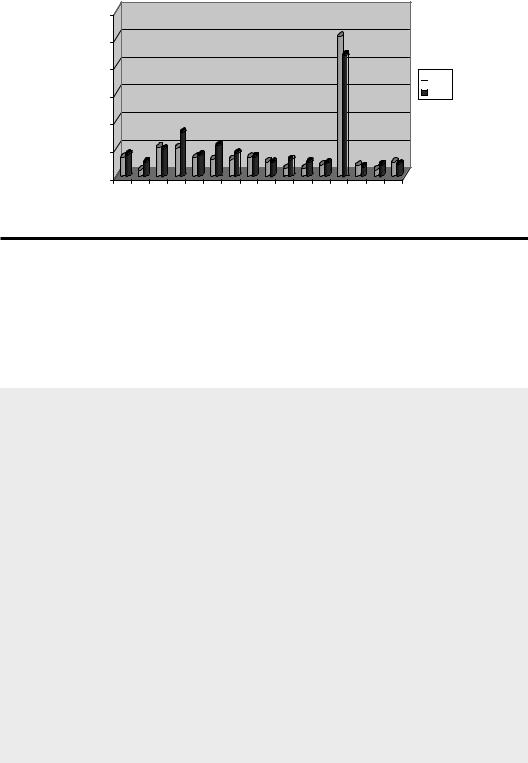

21.3.2 Inventory of Government Personnel

Table 21.1 and Figure 21.2 show the inventory of government personnel from 1964 to 2008. National government agencies (NGAs), including state universities and colleges (SUCs), constitute the bulk of government personnel comprising 74% in 1964, 65% in 1994, 65% in 2004, and 63% in 2008. This is followed by LGUs at 26% in 1964, 25% in 2004, and an increase to 29% in 2008. GOCCs comprise 7% in 2004 and 8% in 2008. Table 21.1 also shows that the number of government personnel in 2008 is smaller by 162,161 compared to 2004. Figure 21.3 shows the employment pattern of the NGAs, GOCCs, and the LGUs.

The LGC transferred some 70,283 personnel of devolved functions from NGAs to LGUs. The Department of Agriculture (17,673), Department of Health (DOH) (45,896), and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (4,144) were heavily affected (Manasan 2004) The local government system consists of 80 provinces, 121 cities, 1,509 municipalities, and 41,994 barangays (or villages). Local governments are tasked to promote the general welfare of the people and provide a broad range of services that are administrative, corporate, regulatory, and developmental in nature.

Geographically, the National Capital Region (NCR) has the most number of government employees with 506,103 in 2008, followed by Region 3 with 104,354, and Region 4 with 100,758 employees. CARAGA and Region 2 have the smallest workforce among the regions, with 23,186 and 23,258 employees, respectively (Figure 21.4).

In 2008, the Department of Education (DepEd), the DOH, and the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) had the most number of employees of NGAs with 519,954 (51.92%), 27,906 (2.79%), and 27,826 (2.78%), respectively (CSC 2008).

As the central government personnel agency, the CSC is mandated to establish a career service and adopt measures to promote morale, efficiency, integrity, responsiveness, progressiveness, and courtesy in the civil service. It shall strengthen the merit and rewards system, integrate all human resources development programs for all levels and ranks, and institutionalize a management climate conducive to public accountability (1987 Constitution, Article IX, Sections 2–3).

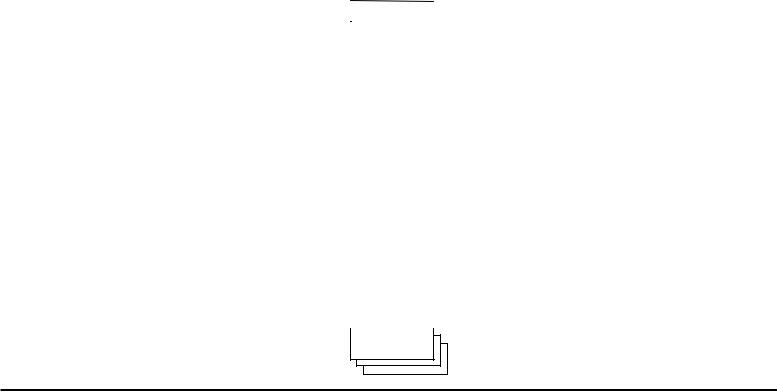

In 1987, the Administrative Code was adopted to elaborate on the key principles and policies for the Philippine administrative system. It reiterates that civil servants are appointed based on “pre-determined merit and a competitive technical examination.” It provides for the rights to selforganization and the benefits of government employees. It prohibits government employees from participating in partisan politics. It also mandates the CSC to uphold due process when investigating offenses by civil servants. The organizational structure of the CSC is shown in Figure 21.5.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Table 21.1 Inventory of Government Personnel, 1964–2008

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1964 |

|

1974 |

|

1984 |

|

1994 |

|

2004 |

|

2008 |

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Level |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NGAs |

201,401 |

|

74 |

194,735 |

|

70 |

667,114 |

|

67 |

796,795 |

|

65 |

1,001,495 |

|

68 |

832,676 |

|

63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GOCCs |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

134,453 |

|

14 |

112,858 |

|

9 |

103,977 |

|

7 |

99,360 |

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LGUs |

71,444 |

|

26 |

85,432 |

|

30 |

189,878 |

|

19 |

316,023 |

|

26 |

370,227 |

|

25 |

381,502 |

|

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Totals |

272,845 |

|

100 |

280,167 |

|

100 |

991,445 |

|

100 |

1,225,676 |

|

100 |

1,475,699 |

|

100 |

1,313,538 |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from CSC 2004; CSC, 2008 Inventory of Government Personnel, 2008; updated by the authors.

Asia Southeast in Administration Public 428

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Civil Service System in the Philippines 429

100% |

|

|

19% |

|

|

|

|

|

90% |

26% |

30% |

26% |

25% |

29% |

|

||

80% |

|

|

||||||

0% |

|

14% |

|

7% |

|

|

||

70% |

0% |

9% |

8% |

|

||||

|

|

LGUs |

||||||

60% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

GOCCs |

||

50% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

40% |

74% |

70% |

67% |

65% |

68% |

63% |

NGA |

|

30% |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

20% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0% |

1964 |

1974 |

1984 |

1994 |

2004 |

2008 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 21.2 Distribution of government personnel, 1964–2008. Source: by the authors.

The CSC, being one of the three independent Constitutional Commissions, has adjudicative power. Thus, it renders final arbitration of disputes and civil service personnel matters.3 Since then, the CSC has been responsible for recruiting, building, maintaining, and retaining the government workforce. The CSC also underwent changes through the inclusion of a three-man body and the introduction the Career Executive Service (CES) (Box 21.1).

Positions in the Philippine civil service are categorized into “career” and “non-career.” Career officers are further categorized into first, second, and third levels. These are permanent positions with security of tenure. Promotion to higher levels of appointment must meet certain qualification standards and performance. Table 21.2 lists the career appointments in the civil service system.

Non-career service refers to appointments that have a fi xed-term or temporary status in government. These appointments are not based on the usual tests of merit and fitness, and tenure is otherwise limited. They include “elective officials” (national and sub-national); appointment of officers holding positions at the pleasure of the president; chairpersons and members of the commissions and boards with a fi xed term of office, including their personal and confidential staff; contractual personnel; and the emergency and seasonal personnel.

In 2008, there were 1,153,651 CES and 159,887 non-career personnel. The government also hired 281,586 employees under contracts of service and job orders (CSC 2008). Table 21.3 and Figure 21.6 show the number of career service personnel by appointment level. Career appointments

1,200,000 |

|

|

1,000,000 |

|

|

800,000 |

|

|

600,000 |

NGA |

|

GOCCs |

||

|

||

400,000 |

LGUs |

200,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

1964 |

1974 |

1984 |

1994 |

2004 |

2008 |

Figure 21.3 Government employment, 1964–2008. Source: by the authors.

3The other two are the Commission on Audit (COA) and the Commission on Elections (COMELEC).

©2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

430 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

600,000

500,000

400,000

2008

2008

2004

300,000

200,000

100,000

0

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

NCR |

CAR |

CARAGA |

ARMM |

Figure 21.4 Geographical distribution of government personnel, 2004 and 2008. Source: Adapted from (CSC 2004 and CSC, 2008 Inventory of Government Personnel, 2008.)

at the second level (professional and technical) stood at 67.3% or 776,182, while 30.4% or 350,824 were at the first level (clerical, trades and crafts group). The third level (executive) comprised 1.2% or 13,316 appointments. Non-executive career appointments were at 1.2% or 13,329.

Non-career service casual employees comprised 60.9%, while contractual, elective, and co-ter- minus positions were at 13.1%, 13%, and 12.1%, respectively (Table 21.4 and Figure 21.7). About

BOX 21.1 THE CAREER EXECUTIVE SERVICE

CES is the third level or the managerial class in the group of career positions in the Philippine civil service. It was created by Presidential Decree No. 1 to “form a continuing pool of wellselected and development-oriented career administrators who shall provide competent and faithful service.” The CES is also a public personnel system program, but separate from the program for the first two levels of positions in the Philippine civil service.

Career Executive Service Officers (CESOs) are appointed to ranks and only assigned to CES positions. As such, they can be re-assigned or transferred from one CES position to another and from one office to another, but not more often than once every two years. The CES is similar to the Armed Forces and the Foreign Service where the officers are also appointed to ranks and assigned to positions.

The Career Executive Service Board (CESB) is the governing body of the CES. CESB is mandated to promulgate rules, standards, and procedures on the selection, classification, compensation, and career development of members of the CES.

The positions in the CES are career positions above division chief level that exercise managerial functions. These are the positions of undersecretary, assistant secretary bureau director, bureau assistant director, regional director, assistant regional director, department service chief, and other executive positions of equivalent rank as may be identified by the CESB.

Source: CESB website at www.cesboard.gov.ph.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O ce of the Chair |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O ce of the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Career |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commissioners |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Executive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O ce of the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Service Board |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Assistant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commissioners |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O ce for Personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Internal Audit |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Service |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Development (OPMD) |

|

|

|

|

O ce for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(IAS) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Planning and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Administration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O ce for Financial |

|

|

|

|

(OPA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commission |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and Assets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secretariat and |

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Liaison O ce |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(OFAM) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(CSLO) |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O ce for |

|

|

|

|

|

Examination, |

|

|

Personnel |

|

|

Human |

|

|

|

|

Integrated |

|

|

Public |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Career |

|

|

O ce for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personnel |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Recruitment |

|

|

Policies and |

|

|

Resource |

|

|

Records |

|

|

Assistance |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Executive |

|

|

Legal A airs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Relations |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

& Placement |

|

|

Standards |

|

|

Development |

|

|

Management |

|

|

Information |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Service |

|

|

(OLA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

O ce (PRO) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

O ce (ERPO) |

|

|

O ce (PPSO) |

|

|

O ce (HRDO) |

|

|

O ce (IRMO) |

|

|

O ce (PAIO) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

(OCES) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Regional O ces |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Field O ces

AU: Please

provide callout Figure 21.5 Organizational structure of the CSC. Source: CSC.

431 Philippines the in System Service Civil

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC