- •Public Administration And Public Policy

- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •About The Authors

- •Comments On Purpose and Methods

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Culture

- •1.3 Colonial Legacies

- •1.3.1 British Colonial Legacy

- •1.3.2 Latin Legacy

- •1.3.3 American Legacy

- •1.4 Decentralization

- •1.5 Ethics

- •1.5.1 Types of Corruption

- •1.5.2 Ethics Management

- •1.6 Performance Management

- •1.6.2 Structural Changes

- •1.6.3 New Public Management

- •1.7 Civil Service

- •1.7.1 Size

- •1.7.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •1.7.3 Pay and Performance

- •1.7.4 Training

- •1.8 Conclusion

- •Contents

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Historical Developments and Legacies

- •2.2.1.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of King as Leader

- •2.2.1.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.1.3 Third Legacy: Traditions of Hierarchy and Clientelism

- •2.2.1.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition of Reconciliation

- •2.2.2.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of Bureaucratic Elites as a Privileged Group

- •2.2.2.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.2.3 Third Legacy: The Practice of Staging Military Coups

- •2.2.2.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition for Military Elites to be Loyal to the King

- •2.2.3.1 First Legacy: Elected Politicians as the New Political Boss

- •2.2.3.2 Second Legacy: Frequent and Unpredictable Changes of Political Bosses

- •2.2.3.3 Third Legacy: Politicians from the Provinces Becoming Bosses

- •2.2.3.4 Fourth Legacy: The Problem with the Credibility of Politicians

- •2.2.4.1 First Emerging Legacy: Big Businessmen in Power

- •2.2.4.2 Second Emerging Legacy: Super CEO Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.4.3 Third Emerging Legacy: Government must Serve Big Business Interests

- •2.2.5.1 Emerging Legacy: The Clash between Governance Values and Thai Realities

- •2.2.5.2 Traits of Governmental Culture Produced by the Five Masters

- •2.3 Uniqueness of the Thai Political Context

- •2.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •3.1 Thailand Administrative Structure

- •3.2 History of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.2.1 Thailand as a Centralized State

- •3.2.2 Towards Decentralization

- •3.3 The Politics of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.3.2 Shrinking Political Power of the Military and Bureaucracy

- •3.4 Drafting the TAO Law 199421

- •3.5 Impacts of the Decentralization Reform on Local Government in Thailand: Ongoing Challenges

- •3.5.1 Strong Executive System

- •3.5.2 Thai Local Political System

- •3.5.3 Fiscal Decentralization

- •3.5.4 Transferred Responsibilities

- •3.5.5 Limited Spending on Personnel

- •3.5.6 New Local Government Personnel System

- •3.6 Local Governments Reaching Out to Local Community

- •3.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Corruption: General Situation in Thailand

- •4.2.1 Transparency International and its Corruption Perception Index

- •4.2.2 Types of Corruption

- •4.3 A Deeper Look at Corruption in Thailand

- •4.3.1 Vanishing Moral Lessons

- •4.3.4 High Premium on Political Stability

- •4.4 Existing State Mechanisms to Fight Corruption

- •4.4.2 Constraints and Limitations of Public Agencies

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 History of Performance Management

- •5.2.1 National Economic and Social Development Plans

- •5.2.2 Master Plan of Government Administrative Reform

- •5.3 Performance Management Reform: A Move Toward High Performance Organizations

- •5.3.1 Organization Restructuring to Increase Autonomy

- •5.3.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.3 Knowledge Management Toward Learning Organizations

- •5.3.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.3.5 Challenges and Lessons Learned

- •5.3.5.1 Organizational Restructuring

- •5.3.5.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.5.3 Knowledge Management

- •5.3.5.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.4.4 Outcome of Budgeting Reform: The Budget Process in Thailand

- •5.4.5 Conclusion

- •5.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •6.1.1 Civil Service Personnel

- •6.1.2 Development of the Civil Service Human Resource System

- •6.1.3 Problems of Civil Service Human Resource

- •6.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •6.2.1 Main Feature

- •6.2.2 Challenges of Recruitment and Selection

- •6.3.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.2 Salary Management

- •6.4.2.2 Performance Management and Salary Increase

- •6.4.3 Position Allowance

- •6.4.5 National Compensation Committee

- •6.4.6 Retirement and Pension

- •6.4.7 Challenges in Compensation

- •6.5 Training and Development

- •6.5.1 Main Feature

- •6.5.2 Challenges of Training and Development in the Civil Service

- •6.6 Discipline and Merit Protection

- •6.6.1 Main Feature

- •6.6.2 Challenges of Discipline

- •6.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •English References

- •Contents

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Setting and Context

- •7.3 Malayan Union and the Birth of the United Malays National Organization

- •7.4 Post Independence, New Economic Policy, and Malay Dominance

- •7.5 Centralization of Executive Powers under Mahathir

- •7.6 Administrative Values

- •7.6.1 Close Ties with the Political Party

- •7.6.2 Laws that Promote Secrecy, Continuing Concerns with Corruption

- •7.6.3 Politics over Performance

- •7.6.4 Increasing Islamization of the Civil Service

- •7.7 Ethnic Politics and Reforms

- •7.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 System of Government in Malaysia

- •8.5 Community Relations and Emerging Recentralization

- •8.6 Process Toward Recentralization and Weakening Decentralization

- •8.7 Reinforcing Centralization

- •8.8 Restructuring and Impact on Decentralization

- •8.9 Where to Decentralization?

- •8.10 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia: General Observations

- •9.2.1 Factors of Corruption

- •9.3 Recent Corruption Scandals

- •9.3.1 Cases Involving Bureaucrats and Executives

- •9.3.2 Procurement Issues

- •9.4 Efforts to Address Corruption and Instill Ethics

- •9.4.1.1 Educational Strategy

- •9.4.1.2 Preventive Strategy

- •9.4.1.3 Punitive Strategy

- •9.4.2 Public Accounts Committee and Public Complaints Bureau

- •9.5 Other Efforts

- •9.6 Assessment and Recommendations

- •9.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •10.1 History of Performance Management in the Administrative System

- •10.1.1 Policy Frameworks

- •10.1.2 Organizational Structures

- •10.1.2.1 Values and Work Ethic

- •10.1.2.2 Administrative Devices

- •10.1.2.3 Performance, Financial, and Budgetary Reporting

- •10.2 Performance Management Reforms in the Past Ten Years

- •10.2.1 Electronic Government

- •10.2.2 Public Service Delivery System

- •10.2.3 Other Management Reforms

- •10.3 Assessment of Performance Management Reforms

- •10.4 Analysis and Recommendations

- •10.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.2.1 Public Service Department

- •11.2.2 Public Service Commission

- •11.2.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •11.2.4 Malaysian Administrative Modernization and Management Planning Unit

- •11.2.5 Administrative and Diplomatic Service

- •11.4 Civil Service Pension Scheme

- •11.5 Civil Service Neutrality

- •11.6 Civil Service Culture

- •11.7 Reform in the Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.2.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.3.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.3.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.4.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.4.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.5.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.5.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.6.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.6.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.7 Public Administration and Society

- •12.7.1 Public Accountability and Participation

- •12.7.2 Administrative Values

- •12.8 Societal and Political Challenge over Bureaucratic Dominance

- •12.9 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.3 Constitutional Framework of the Basic Law

- •13.4 Changing Relations between the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •13.4.1 Constitutional Dimension

- •13.4.1.1 Contending Interpretations over the Basic Law

- •13.4.1.3 New Constitutional Order in the Making

- •13.4.2 Political Dimension

- •13.4.2.3 Contention over Political Reform

- •13.4.3 The Economic Dimension

- •13.4.3.1 Expanding Intergovernmental Links

- •13.4.3.2 Fostering Closer Economic Partnership and Financial Relations

- •13.4.3.3 Seeking Cooperation and Coordination in Regional and National Development

- •13.4.4 External Dimension

- •13.5 Challenges and Prospects in the Relations between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •References

- •Contents

- •14.1 Honesty, Integrity, and Adherence to the Law

- •14.2 Accountability, Openness, and Political Neutrality

- •14.2.1 Accountability

- •14.2.2 Openness

- •14.2.3 Political Neutrality

- •14.3 Impartiality and Service to the Community

- •14.4 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Brief Overview of Performance Management in Hong Kong

- •15.3.1 Measuring and Assessing Performance

- •15.3.2 Adoption of Performance Pledges

- •15.3.3 Linking Budget to Performance

- •15.3.4 Relating Rewards to Performance

- •15.4 Assessment of Outcomes of Performance Management Reforms

- •15.4.1 Are Departments Properly Measuring their Performance?

- •15.4.2 Are Budget Decisions Based on Performance Results?

- •15.4.5 Overall Evaluation

- •15.5 Measurability of Performance

- •15.6 Ownership of, and Responsibility for, Performance

- •15.7 The Politics of Performance

- •15.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Structure of the Public Sector

- •16.2.1 Core Government

- •16.2.2 Hybrid Agencies

- •16.2.4 Private Businesses that Deliver Public Services

- •16.3 Administrative Values

- •16.4 Politicians and Bureaucrats

- •16.5 Management Tools and their Reform

- •16.5.1 Selection

- •16.5.2 Performance Management

- •16.5.3 Compensation

- •16.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 The Philippines: A Brief Background

- •17.4 Philippine Bureaucracy during the Spanish Colonial Regime

- •17.6 American Colonial Regime and the Philippine Commonwealth

- •17.8 Independence Period and the Establishment of the Institute of Public Administration

- •17.9 Administrative Values in the Philippines

- •17.11 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Toward a Genuine Local Autonomy and Decentralization in the Philippines

- •18.2.1 Evolution of Local Autonomy

- •18.2.2 Government Structure and the Local Government System

- •18.2.3 Devolution under the Local Government Code of 1991

- •18.2.4 Local Government Finance

- •18.2.5 Local Government Bureaucracy and Personnel

- •18.3 Review of the Local Government Code of 1991 and its Implementation

- •18.3.1 Gains and Successes of Decentralization

- •18.3.2 Assessing the Impact of Decentralization

- •18.3.2.1 Overall Policy Design

- •18.3.2.2 Administrative and Political Issues

- •18.3.2.2.1 Central and Sub-National Role in Devolution

- •18.3.2.2.3 High Budget for Personnel at the Local Level

- •18.3.2.2.4 Political Capture by the Elite

- •18.3.2.3 Fiscal Decentralization Issues

- •18.3.2.3.1 Macroeconomic Stability

- •18.3.2.3.2 Policy Design Issues of the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.3.2.3.4 Disruptive Effect of the Creation of New Local Government Units

- •18.3.2.3.5 Disparate Planning, Unhealthy Competition, and Corruption

- •18.4 Local Governance Reforms, Capacity Building, and Research Agenda

- •18.4.1 Financial Resources and Reforming the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.4.3 Government Functions and Powers

- •18.4.6 Local Government Performance Measurement

- •18.4.7 Capacity Building

- •18.4.8 People Participation

- •18.4.9 Political Concerns

- •18.4.10 Federalism

- •18.5 Conclusions and the Way Forward

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Control

- •19.2.1 Laws that Break Up the Alignment of Forces to Minimize State Capture

- •19.2.2 Executive Measures that Optimize Deterrence

- •19.2.3 Initiatives that Close Regulatory Gaps

- •19.2.4 Collateral Measures on Electoral Reform

- •19.3 Guidance

- •19.3.1 Leadership that Casts a Wide Net over Corrupt Acts

- •19.3.2 Limiting Monopoly and Discretion to Constrain Abuse of Power

- •19.3.3 Participatory Appraisal that Increases Agency Resistance against Misconduct

- •19.3.4 Steps that Encourage Public Vigilance and the Growth of Civil Society Watchdogs

- •19.3.5 Decentralized Guidance that eases Log Jams in Centralized Decision Making

- •19.4 Management

- •19.5 Creating Virtuous Circles in Public Ethics and Accountability

- •19.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today

- •20.3 Past Reform Initiatives of the Philippine Public Administrative System

- •20.4.1 Rebuilding Institutions and Improving Performance

- •20.4.1.1 Size and Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.1.2 Privatization

- •20.4.1.3 Addressing Corruption

- •20.4.1.5 Improving Work Processes

- •20.4.2 Performance Management Initiatives for the New Millennium

- •20.4.2.1 Financial Management

- •20.4.2.2 New Government Accounting System

- •20.4.2.3 Public Expenditure Management

- •20.4.2.4 Procurement Reforms

- •20.4.3 Human Resource Management

- •20.4.3.1 Organizing for Performance

- •20.4.3.2 Performance Evaluation

- •20.4.3.3 Rationalizing the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.3.4 Public Sector Compensation

- •20.4.3.5 Quality Management Systems

- •20.4.3.6 Local Government Initiatives

- •20.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Country Development Context

- •21.3 Evolution and Current State of the Philippine Civil Service System

- •21.3.1 Beginnings of a Modern Civil Service

- •21.3.2 Inventory of Government Personnel

- •21.3.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •21.3.6 Training and Development

- •21.3.7 Incentive Structure in the Bureaucracy

- •21.3.8 Filipino Culture

- •21.3.9 Bureaucratic Values and Performance Culture

- •21.3.10 Grievance and Redress System

- •21.4 Development Performance of the Philippine Civil Service

- •21.5 Key Development Challenges

- •21.5.1 Corruption

- •21.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 History

- •22.3 Major Reform Measures since the Handover

- •22.4 Analysis of the Reform Roadmap

- •22.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •23.1 Decentralization, Autonomy, and Democracy

- •23.3.1 From Recession to Take Off

- •23.3.2 Politics of Growth

- •23.3.3 Government Inertia

- •23.4 Autonomy as Collective Identity

- •23.4.3 Social Group Dynamics

- •23.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Functions and Performance of the Commission Against Corruption of Macao

- •24.2.1 Functions

- •24.2.2 Guidelines on the Professional Ethics and Conduct of Public Servants

- •24.2.3 Performance

- •24.2.4 Structure

- •24.2.5 Personnel Establishment

- •24.3 New Challenges

- •24.3.1 The Case of Ao Man Long

- •24.3.2 Dilemma of Sunshine Law

- •24.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Theoretical Basis of the Reform

- •25.3 Historical Background

- •25.4 Problems in the Civil Service Culture

- •25.5 Systemic Problems

- •25.6 Performance Management Reform

- •25.6.1 Performance Pledges

- •25.6.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.7 Results and Problems

- •25.7.1 Performance Pledge

- •25.7.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.8 Conclusion and Future Development

- •References

- •Contents

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Civil Service System

- •26.2.1 Types of Civil Servants

- •26.2.2 Bureaucratic Structure

- •26.2.4 Personnel Management

- •26.4 Civil Service Reform

- •26.5 Conclusion

- •References

360 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

Table 18.2 (continued) |

Devolved Functions and Key Features of the 1991 LGC |

Devolved functions |

Features |

|

|

|

• Inspect food products and imposing quarantines |

|

• Enforce a national building code |

|

• Operate tricycles |

|

• Process and approve subdivision plans |

|

• Establish cockpits and holding cockfights |

|

|

3. Increase financial |

• Broadens their taxing powers |

resources of LGUs |

• Provides them with a specific share in the national wealth |

|

|

|

exploited in their area (e.g., mining, fishery, and forestry charges) |

|

• Increases LGU share in the national internal revenue taxes, i.e., |

|

internal revenue allotments [IRAs] from a previous low of 11% to as |

|

much as 40% |

|

|

4. Legitimize |

• Allocates to NGOs and POs specific seats in local special bodies, |

participation for |

which include local development councils, local health boards, |

civil society in |

and local school boards |

local governance |

• Promotes local accountability and answerability through recall and |

|

|

|

people’s initiative |

|

|

5. Authorize |

• Provides the foundation for LGU to enter into build-operate- |

entrepreneurial |

transfer (BOT) arrangements with the private sector, float bonds, |

and development |

obtain loans from local private institutions |

activities by LGUs |

|

|

|

Source: LGC of 1991; Brillantes, A., Innovations and Excellence in Local Governance: Undestanding Local Governments in the Philippines, UP National College of Public Administration and Governance, Quezon City, 2003.

automatic release of IRA share to LGUs to avoid central government control over it, thereby abolishing a system of patronage to the national government leadership. It encouraged local governments to allocate at least 20% of their fiscal resources on development projects.

18.2.4 Local Government Finance

The LGC provided three main sources of revenue for the LGUs. These include (1) locally generated revenues from local tax and non-tax sources; (2) the IRA fiscal transfers, shares from the exploitation of national wealth, and other grants; and (3) external sources such as loans/borrowing, issuance of bonds, and private sector participation.4

Local governments are given the authority to levy and collect local taxes (real property and business taxes) and non-taxes such as fees, user charges, and receipts from economic enterprises. Real property and business taxes are their main income sources. However, tax assignment varies from each level of local government—provinces, city, municipal, and barangays. Cities assume all taxing powers of both the provinces and municipalities.

4 See Gatmaytan (2004) for legal bases.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Decentralization and Local Governance in the Philippines 361

180,000

160,000

140,000

120,000

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

0

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

|

Local sources (tax and non tax) |

|

|

|

Total expenditure |

|

|||||||

Figure 18.2 Aggregate LGUs expenditure and local sources (in million pesos). Source: Basic data from the Bureau of Local Government Finance (BLGF).

Moreover, LGUs may borrow from banks—but limited to government financial institutions (GFIs) and the municipal development fund office (MDFO)—and float bonds for financing local public investments. They can also engage in partnership ventures such as build-operate-transfer (BOT) schemes to build infrastructure and operate public services.

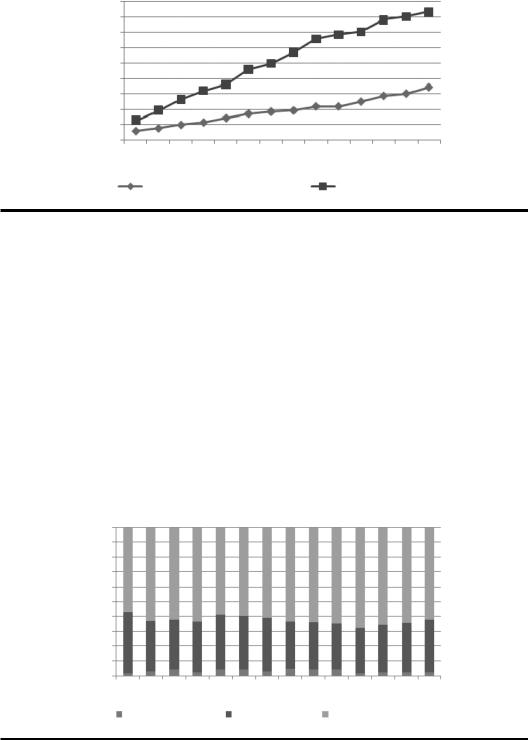

Since the implementation of the LGC in 1992, it can be noted from Figure 18.2 that local government expenditure and locally generated income have been increasing. However, the gap between the two continues to widen. This gap is largely filled by intergovernmental fiscal transfers from the central government, particularly the IRA.

Figure 18.3 shows the trend of the consolidated local revenue sources of local governments— local income sources, IRA and shares, and borrowing. Locally generated revenues range from 31% to 41%, loans/borrowing from 1% to 5%, while allotment and shares range from 57% to 68% of local revenues with the lowest in 1992 and the highest in 2002.

The figures clearly indicate that the IRA constitutes a very significant amount of revenues for LGUs and remains a substantial balancing factor for local government budgets. However, Pardo

100%

90%

80%

70% 57% 63% 62% 63% 59% 60% 61% 64% 64% 65% 68% 66% 64% 62%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20% 41% 34% 34% 34% 37% 36% 36% 32% 32% 32% 31% 33% 34% 36%

10%

0% |

1% |

|

1992 |

||

|

Loan

3% |

4% |

2% |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

and borrowing

4%

1996

4% |

3% |

5% |

4% |

4% |

1% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

Local sources (%) |

|

Allotment and share (%) |

||||||

Figure 18.3 Percentage share of aggregate local revenues: IRA and other shares, local sources, and borrowing/loans. Source: Basic data from BLGF.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

362 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

(2005) observed that the dependency ratios of LGUs are as follows: 75% of provinces are 90% dependent; 75% of municipalities are 88% dependent; and 50% of cities are 45% dependent.5

18.2.5 Local Government Bureaucracy and Personnel

The composition of LGU personnel to the entire government bureaucracy has been changing over the past three decades. With the devolution of services under the LGC, about 70,283 personnel were transferred from the national government agencies (NGAs) to local governments. The Department of Health (45,896), the Department of Agriculture (17,673), and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (4,144) were heavily affected by devolution (Manasan 2004).

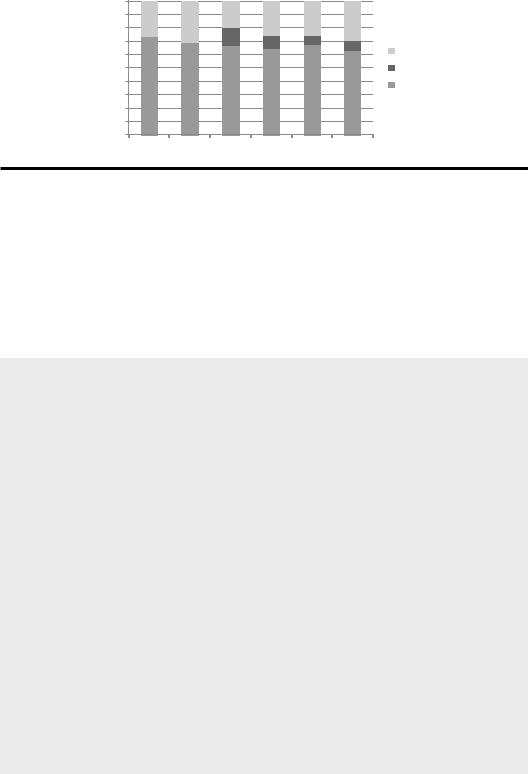

Table 18.3 and Figure 18.4 indicate the size of LGU personnel vis-à-vis that of the NGAs and government-owned and controlled corporations (GOCCs) over the past four decades. Between 1984 and 1994, the percentage share of LGU personnel from the total number of civil servants has increased by 7% from 19% to 26%. There has been an increase of about 126,000 local government personnel since the 1983 LGC, which is slightly lower to that of the NGAs at 130,000 civil servants. Box 18.1 defines some the terms used.

The 2008 figures indicate that 29% of total civil service personnel come from the LGUs; however, the increase can largely be attributed to the ongoing rationalization program under Executive Order (EO) 366.6 Subsequently, EO 444 was also issued directing the Department of the Interior and Local Government to conduct a strategic review on the continuing decentralization and devolution of the services and functions of the national government to LGUs in support of the rationalization program of functions and agencies of the executive branch.

Nonetheless, there has been a substantial decrease of NGA personnel between 2004 and 2008 at the NGAs, thereby increasing the percentage composition of LGUs by 4%.

The LGC provides that LCEs appoint local government staff and personnel with the exception of the local government treasurer, who is appointed by the secretary (minister) of the Department of Finance (DOF) (Ilago 2007). Career and non-career civil servants comprise the local government bureaucracy. Of the 381,502 local civil servants in 2008, 71% or 272,610 personnel are career officials and 29% or 108,892 are non-career officials.

The career officers mostly belong to the fi rst level at 62%, followed by the second level at 37%, and the third level and non-executive with less than half of 1%, respectively. On the other hand, non-career positions are largely fi lled by casual employees7 at 63%, then by elective officials at 19%, co-terminus staff at 10% and 8% contractual, and one-half percent non-career executive positions. Table 18.4 shows the numbers and corresponding percentages of career and non-career positions. Figure 18.5 shows the distribution of non-career LG personnel by type of appointment.

5 It should be noted however that if the data on each level of government are grouped in percentile; we can observe a totally different picture. The sub-section on LG finance draws from Tiu Sonco (2009).

6It instructs the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) and the Civil Service Commission (CSC) to pursue a rationalization program for the executive branch. It also requires rationalization and/or abolition of functions to avoid duplication and overlaps in government agencies to ensure government efficiency. Special benefits and separation packages have been put forward for employees who would be affected.

7For non-career civil servants, a casual employee may refer to a person whose appointment is based on an emergency or seasonal basis and whose salary is drawn from lump-sum appropriation; while a contractual appointment is issued to hire a person on a project basis or depending on the project being undertaken (Tagum City 2005).

©2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Table 18.3 Philippine Government Personnel, 1964–2008

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1964 |

|

1974 |

|

1984 |

|

1994 |

|

2004 |

|

2008 |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Level |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

|

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

|

% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NGAs |

201,401 |

|

74 |

194,735 |

|

70 |

667,114 |

|

67 |

796,795 |

|

65 |

1,001,495 |

68 |

832,676 |

|

63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GOCCs |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

134,453 |

|

14 |

112,858 |

|

9 |

103,977 |

7 |

99,360 |

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LGUs |

71,444 |

|

26 |

85,432 |

|

30 |

189,878 |

|

19 |

316,023 |

|

26 |

370,227 |

25 |

381,502 |

|

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

272,845 |

|

100 |

280,167 |

|

100 |

991,445 |

|

100 |

1,225,676 |

|

100 |

1,475,699 |

100 |

1,313,538 |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Basic data from CSC; updated by Authors.

363 Philippines the in Governance Local and Decentralization

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

364 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

100% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

90% |

26% |

30% |

19% |

26% |

25% |

29% |

|

|

80% |

|

|

||||||

0% |

|

14% |

|

7% |

|

|

||

70% |

0% |

9% |

8% |

LGUs |

||||

|

|

|||||||

60% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

GOCCs |

||

50% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

40% |

74% |

70% |

67% |

65% |

68% |

63% |

NGA |

|

30% |

|

|

||||||

20% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0% |

1964 |

1974 |

1984 |

1994 |

2004 |

2008 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 18.4 Distribution of government personnel, 1964–2008. Source: Basic data from the Civil Service Commission.

The local government bureaucracy needs further integration with the Philippine civil service system and human resource development. Although the LGC provides for its professionalization, this has been one policy area that warrants attention if the country is to elevate decentralization to the next level, including a clearer career path, growth, and development. Needless to say, a professionalized and improved quality of local bureaucracy can make a difference in planning, policymaking, and implementation on the ground. Continuity of good plans and programs could be pursued given the political dynamics and short-term limit of the local political leadership.

BOX 18.1 DEFINITION OF TERMS

Career service: the entrance of employees is based on merit and fitness, determined by competitive examinations or on highly technical qualifications. Employees under this category enjoy opportunities for advancement to higher career positions and security of tenure.

Non-career service: the entrance of employees is based on factors other than the usual test of merit and fitness utilized for the career service. Their tenure is limited to a period specified by law or is coterminous with that of the appointing authority or is subject to his pleasure, or is limited to the duration of a particular project for which purpose employment was made.

First level: clerical, trades, crafts, and custodial service positions.

Second level: professional, technical, and scientific positions.

Third level: positions in the Career Executive Service (CES).

Non-executive career: career positions excluded from the CES with salary Grade 25 above (e.g., scientist, professional, foreign services officers, members of the judiciary and prosecution service); third level positions in the LGUs.

Non-career executive: secretaries/officials of cabinet rank who hold their positions at the pleasure of the president; supervisory and executive positions with fi xed terms of office (e.g., chairman and member of Commission and board).

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC