- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace |

|

425 |

|

simple version of the ultimatum game in which Player 1 could only select one of two possible splits between the two players. In one game (call this game 1), the first player could propose that both would walk away with $5 or that the Player 1 would receive $8 and Player 2 would receive $2. In this game, 44 percent of those playing the role of Player 2 rejected the offer if the proposed split was $8 and $2. But in another game (call this game 2), Player 1 could only choose between a split in which Player 1 receives $8 and Player 2 receives $2, or a split in which Player 1 receives $2 and Player 2 receives $8. Only 27 percent of those playing the role of Player 2 rejected an offer that gave them only $2 in this game, though it was exactly the offer that induced 44 percent to reject in game 1. Note that if Player 2’s preferences display inequality aversion as presented in equation 15.1, then rejecting the offer in game 1 means U 2, 8

2, 8 = 2 − α

= 2 − α 8 − 2

8 − 2 < 0 = U

< 0 = U 0, 0

0, 0 . But accepting the split in game 2 implies U

. But accepting the split in game 2 implies U 2, 8

2, 8 = 2 − α

= 2 − α 8 − 2

8 − 2 > 0 = U

> 0 = U 0, 0

0, 0 . Here, it appears that the particular options that were available to Player 1 changed the calculation of what was fair in the eyes of Player 2. In other words, the motives of Player 1 matters as well as the particular split of the money that is realized.

. Here, it appears that the particular options that were available to Player 1 changed the calculation of what was fair in the eyes of Player 2. In other words, the motives of Player 1 matters as well as the particular split of the money that is realized.

Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive

Marketplace

Customers and employees hold firms to a standard of fairness that has sore implications. For example, in 2011 Netflix Inc., a firm that provided streaming movies and DVD rentals through the mail, chose to nearly double the prices for subscriptions at the same time that they limited their customers to either receive DVDs through the mail or to download—but not both. The customer backlash was strong, leading the CEO to apologize several times and provide explanations about how the profit model was changing, and eventually capitulating to incensed customers by allowing both DVD rentals and downloads.

Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard Thaler used surveys of around 100 people to study how we evaluate such actions by firms. For example, 82 percent of participants considered it unfair for a firm to raise the price of snow shovels the day after a major snow storm. Similarly, 83 percent considered it unfair to reduce an employee’s wages even if the market wage for that occupation has declined. It is acceptable, according to 63 percent, however, to reduce the wages of a worker if the firm abandons one activity (e.g., software design) for another in which the going market wages are lower (e.g., software support). Thus, it is okay to cut salary if it is associated with a change in duties.

In general, economists have found that consumers consider it fair for a firm to raise its price to maintain profits when costs are on the rise. However, it is considered unfair to raise prices simply to profit from an increase in demand or to take advantage of market power (e.g., due to a shortage). In other words, raising prices is considered unfair if it will result in a higher profit than some baseline or reference level. This principle is described as dual entitlement. Under dual entitlement, both the consumer and the seller are entitled to a level of benefit given by some reference transaction. This reference transaction is generally given by the status quo. Hence, if costs rise, the seller is allowed to increase prices to maintain the reference profit. However, the seller is not allowed to increase his profit on the transaction if costs do not rise, even if there are shortages of the item. To do so would threaten the consumer. Similar effects can be found in the labor market considering the transaction between an employer and employee. This leads to three notable effects in both consumer and labor markets.

|

|

|

|

|

426 |

|

FAIRNESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL GAMES |

Markets Might Not Clear When Demand Shifts

When increases in demand for a consumer product occur and producer costs do not increase, shortages will occur. This leads to waiting lists or other market-rationing measures because the price is not allowed to rise enough to reduce the quantity demanded. In labor markets, a reduction in demand for outputs generally does not lead to a reduction in wages. Rather, firms maintain wages but reduce the number of employees. Maintaining the same wages but reducing the number of employees generally leads to labor markets that do not clear, resulting in unemployment.

Prices and Wages Might Not Fully Reflect

Quality Differences

If a firm offers two variations of an item that cost identical amounts to manufacture but that differ substantially in value to the consumer, consumers will consider it unfair to charge prices that differ by too much. For example, a majority of football fans might value tickets to the big rivalry game more than when their home team faces other opponents. This should lead to much higher ticket prices for the big game. But fans’ opinions about fairness can limit the increase in price, leading to more fans being willing to purchase tickets for this game at the listed price than there are seats in the stadium. For example, the University of California charged $51 for most of their home games in 2010. However, they charged $66 for a seat at the game against Stanford, their primary rival. This game was sold out, as is the case every year when the two play. Clearly they could charge a much higher price and still fill the stadium. Similar effects are found with peak and offseason prices for hotel rooms.

With regard to wages, this leads to a case where more-productive workers are not paid quite as much as they are worth relative to other workers in the same firm and occupation. For example, many universities pay professors of the same rank similar salaries regardless of their field and level of productivity. This commonly leads to a situation where the most productive faculty are also the most undervalued and thus the most likely to leave for more lucrative work elsewhere. Universities often cannot increase the pay of the most productive faculty to the market rate because it would be perceived as unfair by others who are less productive or less valuable in similar positions.

Prices Are More Responsive to Cost Increases than Decreases

Because consumers are willing to allow producers to increase prices to maintain a reference level of profit, producers are likely to take advantage of this quickly. Alternatively, they may be slow to advertise when costs decline, leading to higher profits. They would only lower prices in response to the potential impact it could have on their competitive position in the market. Producers also have incentives to use temporary discounts to consumers rather than actual price decreases. Price decreases can alter the reference transaction in favor of the consumer, whereas discounts will be viewed as a temporary gain by the consumer. Although there is some evidence that prices respond asymmetrically, there is also some substantial counterevidence.

|

|

|

|

Fairness |

|

427 |

|

On the other hand, there is substantial evidence the wages are slow to decline and quick to increase. This is often referred to as wages being “sticky downward.” The slow decline can lead to prolonged periods of unemployment when market wages decline. This happens when many are willing to work at the going (lower) wages but cannot find employment. Employers will not hire, preferring to keep a smaller workforce at higher salaries rather than being perceived as unfair by cutting salaries of the currently employed. Additionally, employers may be inclined to give workers a portion of their pay in the form of a bonus in order to allow flexibility to reduce pay without being perceived as unfair.

Fairness

Important to note in the case of American Airlines executives and flight attendants is how key the perception of deception was to the flight attendants’ union. Even without the bonuses, it is clear that the outcome would be lopsided. The 10 executives would still be receiving salaries that could not be dreamed of by even the most senior flight attendants. The motive for dropping the agreement wasn’t to create a more-equal sharing of the rewards. The motive was to punish executives who were now perceived to be greedy and deceptive. The perception was that the executives had not negotiated in good faith. The perception of their duplicity drove the flight attendants to drop an otherwise acceptable labor agreement.

Matthew Rabin proposes that people are motivated to help those who are being kind and hurt those who are being unkind. Thus, he suggests that people are not motivated simply to find equal divisions (and sacrifice well-being in order to find them) but that they are also motivated by the intent and motivations of others. When people are willing to sacrifice in order to reward the kindness of others, or to punish the unkindness of others, we refer to them as being motivated by fairness. Rabin proposes that people maximize their utility, which is a sum of their monetary payout, and a factor that represents their preferences for fairness.

Formally, consider any two-player game in which Player 1 chooses among a set of strategies, with his choice represented by the variable a1. Player 2 also chooses among a set of strategies, with his choice represented by a2. As with all games, a strategy represents a planned action in response to each possible decision point in the game. The payoff to each player is completely determined by the strategies of both players, and thus the payout to Player 1 can be represented by a function π1 a1, a2

a1, a2 , and the payout to Player 2 can be represented as π2

, and the payout to Player 2 can be represented as π2 a1, a2

a1, a2 . The Nash equilibrium is thus described as

. The Nash equilibrium is thus described as  a1, a2

a1, a2 where Player 1 selects a1 so as to maximize π1

where Player 1 selects a1 so as to maximize π1 a1, a2

a1, a2 for the given a2 and Player 2 maximizes π2

for the given a2 and Player 2 maximizes π2 a1, a2

a1, a2 for the given a1. Let us suppose that these payout functions represent material outcomes, such as the money rewards generally employed in economic experiments like the ultimatum game. If players are motivated by fairness, their total utility of a particular outcome will depend not only on the material outcome but also on the perception of whether the other player has been kind and whether the decision maker has justly rewarded the other player for his kindness or lack thereof. To specify this part of the utility of the decision maker, we thus need to define a function representing the perceived kindness of the other player and the kindness of the decision maker.

for the given a1. Let us suppose that these payout functions represent material outcomes, such as the money rewards generally employed in economic experiments like the ultimatum game. If players are motivated by fairness, their total utility of a particular outcome will depend not only on the material outcome but also on the perception of whether the other player has been kind and whether the decision maker has justly rewarded the other player for his kindness or lack thereof. To specify this part of the utility of the decision maker, we thus need to define a function representing the perceived kindness of the other player and the kindness of the decision maker.

|

|

|

|

|

428 |

|

FAIRNESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL GAMES |

Let b1 represent Player 2’s beliefs about the strategy that Player 1 will employ, and let b2 represent Player 1’s beliefs about the strategy of Player 2. These perceived strategies will help define whether, for example, Player 1 believes Player 2 is being kind or cruel. We can then define a function f1 a1, b2

a1, b2 , called a kindness function, that represents how kind Player 1 is intending to be toward Player 2. This kindness function can take on negative values, representing the notion that Player 1 is being cruel to Player 2, or positive values, representing the notion that Player 1 is being kind to Player 2. Note that how kind Player 1 is intending to behave is a function of his own strategy, a1, and the strategy he believes the other player is employing, b2. Rabin’s model also assumes that both players agree on the definition of kindness, and thus this kindness function also represents how kind Player 2 would perceive the strategy of a1 by Player 1 to be in response to the strategy a2 = b2 by Player 2. Similarly, Player 2 has a kindness function given by f2

, called a kindness function, that represents how kind Player 1 is intending to be toward Player 2. This kindness function can take on negative values, representing the notion that Player 1 is being cruel to Player 2, or positive values, representing the notion that Player 1 is being kind to Player 2. Note that how kind Player 1 is intending to behave is a function of his own strategy, a1, and the strategy he believes the other player is employing, b2. Rabin’s model also assumes that both players agree on the definition of kindness, and thus this kindness function also represents how kind Player 2 would perceive the strategy of a1 by Player 1 to be in response to the strategy a2 = b2 by Player 2. Similarly, Player 2 has a kindness function given by f2 a2, b1

a2, b1 defined analogously.

defined analogously.

Finally, let c1 represent what Player 1 believes Player 2 believes Player 1’s strategy is and let c2 represent what Player 2 believes Player 1 believes Player 2’s strategy is. This can begin to sound a little tedious. These values are used to help determine if, for example, Player 1 believes that Player 2 believes that Player 1 is being kind or cruel. We can then define the function f 2 b2, c1

b2, c1 , which represents Player 1’s belief about how kind Player 2 is being. Note that this perception is a function both of Player 1’s belief regarding Player 2’s strategy, b2, and Player 1’s belief about what Player 2 believes Player 1’s strategy is, c1. Again, this function takes on negative values if Player 2 is perceived to be cruel, and it takes on positive values if Player 2 is perceived to be kind. Similarly, we can define payer 2’s belief about how kind Player 1 is, f 1

, which represents Player 1’s belief about how kind Player 2 is being. Note that this perception is a function both of Player 1’s belief regarding Player 2’s strategy, b2, and Player 1’s belief about what Player 2 believes Player 1’s strategy is, c1. Again, this function takes on negative values if Player 2 is perceived to be cruel, and it takes on positive values if Player 2 is perceived to be kind. Similarly, we can define payer 2’s belief about how kind Player 1 is, f 1 b1, c2

b1, c2 . With these functions in hand, we can now define Player 1’s utility function as

. With these functions in hand, we can now define Player 1’s utility function as

U1 a1, b2, c1 = π1 a1, b2 + f 2 b2, c1 × f1 a1, b2 . |

15 6 |

The first term represents Player 1’s perception of his material payout for playing strategy a1 given that Player 2 employs strategy b2. The second term represents the utility of fairness. If Player 2 is perceived to be cruel, f 2 b2, c1

b2, c1 will be negative, and Player 1 will be motivated to make f1

will be negative, and Player 1 will be motivated to make f1 a1, b2

a1, b2 more negative by choosing a strategy that is also cruel. Alternatively, if Player 2 is perceived as being kind, f 2

more negative by choosing a strategy that is also cruel. Alternatively, if Player 2 is perceived as being kind, f 2 b2, c1

b2, c1 will be positive, leading Player 1 to choose a strategy that will make f1

will be positive, leading Player 1 to choose a strategy that will make f1 a1, b2

a1, b2 more positive by being more kind. Player 2’s utility function is defined reciprocally as

more positive by being more kind. Player 2’s utility function is defined reciprocally as

U2 a2, b1, c2 = π2 b1, a2 + f 1 b1, c2 × f2 a2, b1 . |

15 7 |

We can then define a fairness equilibrium as the set of strategies  a1, a2

a1, a2 such that a1 solves

such that a1 solves

maxa1 U1 a1, a2, a1 |

15 8 |

and a2 solves |

|

maxa2 U2 a2, a1, a2 , |

15 9 |

|

|

|

|

Fairness |

|

429 |

|

where a1 = b1 = c1, a2 = b2 = c2. Equations 15.8 and 15.9 imply that the fairness equilibrium is equivalent to the notion of a Nash equilibrium, taking into account the utility from fairness, and requiring that all have correct beliefs regarding the intent of the other player. In other words, players are choosing the strategy that makes them the best off they can be given the strategy the other player chooses. Additionally, the equilibrium requires that each player correctly perceives what strategy the opponent will play and that each player correctly perceives that the opponent correctly perceives the strategy the player will play. Given that this is a complicated concept, a few examples with a specific kindness function may be useful.

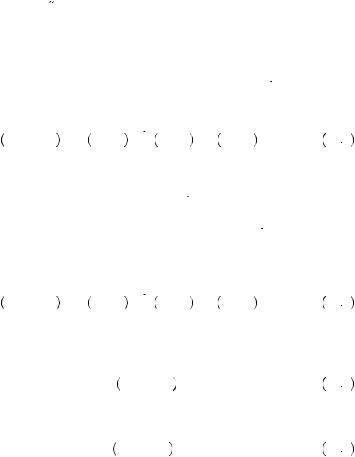

First, consider the classic game often titled “Battle of the Sexes.” This game is intended to represent a husband and wife who wish to go out on a date and can choose between attending the opera or a boxing match. The husband and wife both left the house for work in the morning agreeing to meet each other for a night out but did not have time to agree on which event to attend. Assume the husband and wife have no chance to communicate during the day and are forced to guess about the actions of the other. The material payoffs to the players can be represented as in Figure 15.2. Both would prefer to attend an event together rather than to go to different events. However, the wife would prefer the opera and the husband would prefer boxing. There are two pure strategy Nash equilibria for this game based upon the material payoffs: (boxing, boxing) and (opera, opera). If the wife chooses boxing, the husband is clearly better off choosing boxing and receiving 1 than choosing opera and receiving nothing. Alternatively, given the husband chooses boxing, the wife is clearly better off choosing boxing and receiving 0.5 than choosing opera and receiving nothing. A similar argument can be made for (opera, opera).

Now let us define a kindness function. Rabin suggests one key to defining fairness is whether the other person is hurting himself in order to hurt his opponent. Many different candidates may exist, but for now let’s use

Husband

|

|

|

0 |

if |

aWife = Opera, bHusband = Opera |

|

fWife aWife, bHusband |

= |

− 1 |

if |

aWife = Boxing, bHusband = Opera |

||

− 1 |

if |

15 10 |

||||

|

|

|

aWife = Opera, bHusband = Boxing |

|||

|

|

|

0 |

if |

aWife = Boxing, bHusband = Boxing |

|

|

|

Wife |

|

|

|

|

|

Opera |

|

|

Boxing |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

0.5 |

|

Boxing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

0 |

|

Opera |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.5 |

|

0 |

|

|

FIGURE 15.2 |

|

|

|

|

The Battle of the Sexes |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

430 |

|

FAIRNESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL GAMES |

as the kindness function describing how kind the wife is attempting to be toward her husband. If she believes the husband is going to choose opera, the wife must be trying to be cruel if she decides to choose boxing. To do so costs her one unit of payout to reduce the husband’s payout by 0.5. Hence, we assign this a −1. Similarly, if she believes her husband is going to choose boxing, she must be cruel if she decides to choose opera. In this case she gives up 0.5 in payout to reduce the payout she believes her husband will receive by 1. Thus we assign a −1 to this outcomes also.

The value 0 is assigned to the outcome of (opera, opera) because in this case, the wife is maximizing her payout given that she believes the husband will choose opera. Maximizing your own payout is considered neither kind nor cruel, because the wife is not sacrificing her own well-being to hurt or help her husband. Similarly, we assign a 0 in the case she believes the husband will choose boxing and she chooses boxing, because again she is maximizing her own payout. The husband’s kindness function is defined reciprocally as

|

|

0 |

if |

aHusband = Opera, bWife = Opera |

|

fHusband aHusband, bWife |

= |

− 1 |

if |

aHusband = Boxing, bWife = Opera |

15 11 |

− 1 |

if |

, |

|||

|

|

aHusband = Opera, bWife = Boxing |

|

||

|

|

0 |

if |

aHusband = Boxing, bWife = Boxing |

|

which represents how kind the husband is intending to be toward his wife.

We can also define the set of functions that yield each player’s perception of whether the other player is kind or cruel. We will define f 2 b1, c2

b1, c2 = f2

= f2 c2, b1

c2, b1 , or in this case,

, or in this case,  bWife, cHusband

bWife, cHusband = fHusband

= fHusband  cHusband, bwife

cHusband, bwife , where the latter function is as defined in equation 15.11. Thus, the wife perceives the husband to be kind or cruel using

, where the latter function is as defined in equation 15.11. Thus, the wife perceives the husband to be kind or cruel using

the same measure as the husband himself uses to measure his own kindness or

cruelty. Similarly, |

f 1 b1, c2 = f1 c2, b1 , or in this case, f Wife bHusband, cWife = |

fWife cWife, bHusband |

, where the latter function is as defined in equation 15.10. Thus, the |

husband uses the same functions to assess his wife’s fairness as does the wife to assess her own fairness. In this case, all players agree on the definition of fairness. The fairness

equilibrium requires that all perceptions of strategy align with actual |

strategy, |

aWife = bWife = cWife and aHusband = bHusband = cHusband. Given this restriction, |

we can |

rewrite the game in terms of total utility rather than just material rewards, where substituting into equation 15.7

UWife aWife, bHusband, cWife = πWife aWife, aHusband + f Husband |

aWife, aHusband |

× fWife aWife, aHusband |

15 12 |

|

For example, consider the potential strategy pair in which the wife decides to play the strategy aWife = Boxing and the husband decides to play the strategy aHusband = Opera. To see if this pair of strategies can be a fairness equilibrium, we must see if it is a Nash equilibrium given bWife = cWife = Boxing and bHusband = cHusband = Opera—in other words, where both believe that the wife will choose boxing and the wife believes the husband believes she will choose boxing, and where both believe that the husband will

|

|

|

|

Fairness |

|

431 |

|

choose opera and the husband believes that the wife believes he will choose opera. In this case, the wife will obtain total utility

UWife Boxing, Opera, Boxing

Boxing, Opera, Boxing = πWife

= πWife Boxing, Opera

Boxing, Opera + f Husband

+ f Husband Boxing, Opera

Boxing, Opera

×fWife Boxing, Opera

Boxing, Opera

=0 +  − 1

− 1 ×

×  − 1

− 1 = 1.

= 1.

15

15 13

13

Thus, the wife receives a utility of 1 by choosing to go to boxing when she believes her husband has chosen opera even though he knew she would be going to the opera. In this case, the utility results not from a material payoff (which is zero in this case) but from being cruel to a husband who is treating her poorly. He is making himself worse off in order to hurt her materially, which then gives her the desire to hurt him even at her own expense.

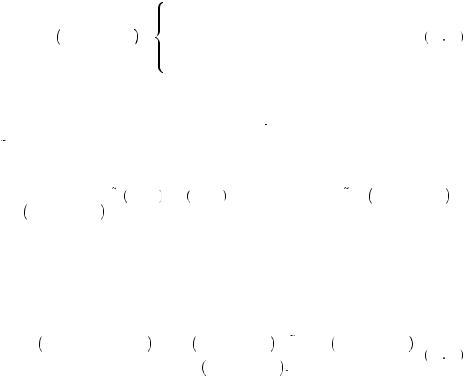

We can make similar calculations for each of the players in each of the outcomes, yielding the final utilities displayed in Figure 15.3. With the utilities defined this way, the fairness equilibria are now given by (boxing, opera) and (opera, boxing). For example, if the wife chooses opera, the husband will be better off choosing boxing and receiving a utility of 1 by intentionally hurting her rather than cooperating with her, going to the opera, and receiving 0.5. Alternatively, given that the husband is choosing boxing, the wife is better off choosing opera and receiving a utility of 1 by intentionally hurting her noncooperative husband than by cooperating with him, going to boxing, and receiving only 0.5.

Similar analysis tells us that (boxing, opera) is a fairness equilibrium, though each player would be just as well off to choose the other event given the other player’s strategy. In this case, the motivation for fairness leads both to choose to punish the spouse rather than cooperate because the rewards for punishing each other are larger than the material rewards for the basic game. This is an extreme example. However, if the original material payoffs had been large relative to the possible values of the kindness functions, the fairness equilibria would have been identical to the Nash equilibria (e.g., if the material rewards had been 160 and 80 rather than 1 and 0.5).

Husband

|

Wife |

|

|

|

|

Opera |

|

Boxing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

0.5 |

|

Boxing |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

Opera |

|

|

|

|

|

0.5 |

1 |

|

FIGURE 15.3 |

|

|

Fairness Utilities in the Battle of the Sexes |

||

|

|

|

|

|