- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

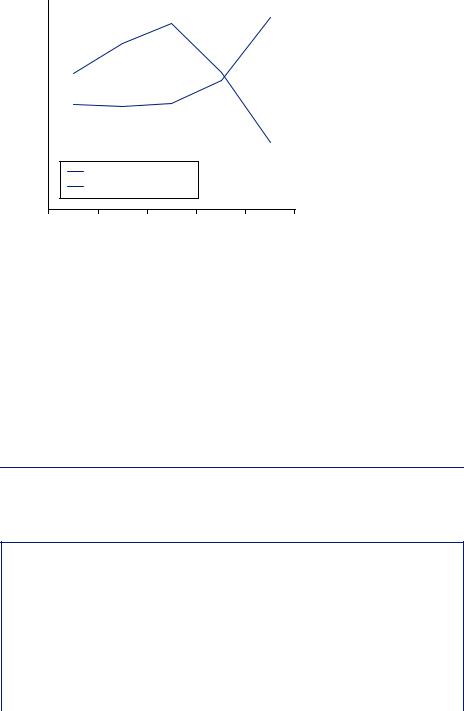

Discounting with a Prospect-Theory Value Function |

|

343 |

|

of value for |

consumption |

Fraction |

immediate |

2

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

The value of delay

Kiss from a movie star 120 volt electric shock

3 |

24 |

hours |

3 |

1 |

10 |

years |

hours |

|

days |

year |

|

Time delay

FIGURE 12.10

The Prospect-Theory Value Function with Intermediate Loss Aversion

Source: Loewenstein, G. “Anticipation and the Valuation of Delayed Consumption.” Economic Journal 97(1987): 666–684, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

than immediately. In both cases, it appears the value of the event is not what has driven the value of delaying, but rather the anticipation of the event. A kiss is a fleeting event. Were you to kiss the movie star of your dreams this instant, you would have little time to enjoy the event itself, and then it would be a memory. Alternatively, if it would take place three days from now, you would be able to talk to your friends about it, fantasize about it, and relish in the anticipation. Similarly, if you receive the 120-volt shock immediately, it would be over in an instant. However, if you were told you would receive the shock in 10 years, you would spend the next 10 years dreading the moment when you would experience the shock. Anticipation and dread are important factors in many intertemporal decisions and can lead to unintuitive behavior.

History and Notes

The hyperbolic discount function has its roots in classic psychology. The function was proposed by George Ainslie, a psychologist, after examining animal experiments with rewards. Many canonical experiments in psychology involve rewarding animals for performing some task. For example, mice are given a pellet of food for pressing a lever or pigeons receive some food after pecking on a button several times. Over time, experimenters had come to recognize that the strength of the incentive provided to the animals was a hyperbolic function of the time between the action

|

|

|

|

|

344 |

|

NAÏVE PROCRASTINATION |

and the time when the reward was received. Ainsley started to compare data examining people’s preferences for delayed consumption. Examining decision makers’ responses to questions about indifference between money or consumption now versus at some future date led him to notice the common-difference effect. Moreover, his training as a psychologist led him to recognize the shape of the discount function that was more convex than the exponential curve as something familiar. Thus was introduced a model of discounting that, along with the prospect-theory value function, has become ubiquitous in behavioral economics. These two models have thus far had a greater impact on the field of economics than any of the other modeling innovations arising from behavioral economics.

Biographical Note

Courtesy of University Relations

at Northwestern University

Robert H. Strotz (1922–1994)

Ph.D., University of Chicago, 1951

Held faculty positions at Northwestern University and University of Illinois at Chicago–Navy Pier

Robert Strotz was born in Illinois and spent almost all of his career at Northwestern University. After completing his undergraduate work in economics in 1942, at the tender age of 20, he was drafted into military service during World War II. He spent much of his service in Europe, where he served in army intelligence. Part of his service included using econometric

and statistical models to estimate the necessary supplies to support the occupied German population. His interest in econometric techniques led him to continue his training in Europe for several years following the war. Following this period of training he returned to the United States to earn his Ph.D. He was hired by Northwestern University four years before he finished his Ph.D. His contributions to economics include welfare theory, economic theories of behavior, and econometrics. Many of his works are concerned with foundational principles of welfare economics: Is utility measurable? How should income be distributed? Additionally, he made substantive contributions to the practice and interpretation of econometrics. His explorations of behavioral models of dynamic choice can truly be considered an offshoot of his interest in welfare economics. The general model he proposed has become a foundation point for modern behavioral economists examining time-inconsistent preferences. Strotz served on the editorial board for many of the most highly regarded journals in economics, including a 15-year stint as editor of Econometrica. He also served for a time as chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. In 1970 he was named president of Northwestern University, where he contributed substantially to the growth and vitality of that institution. Some see Strotz’s leadership as key in attracting the faculty and endowment that made Northwestern one of the top research universities in the world.

|

|

|

|

References |

|

345 |

|

T H O U G H T Q U E S T I O N S

1.Many have erroneously described hyperbolic discounting as an extreme bias toward current consumption. Describe why this is a false statement. Explain intuitively what hyperbolic discounting does to decisions involving intertemporal choice.

2.Naïve hyperbolic discounting leads people to make plans that are never executed. However, there are many reasons people might not execute plans. What other reasons might lead someone to abandon a plan for the future? What distinguishes plans that are not executed owing to hyperbolic discounting from alternative explanations for not executing plans? Do hyperbolic discounters regret not executing their plans?

3.Many people display something like hyperbolic discounting. Some businesses thrive on supporting this sort of short-term excess. For example, several establishments offer payday loans—short-term loans with ultrahigh interest rates designed to be paid off the next time the person is paid.

(a)Suppose you were considering opening such a payday loan establishment. Given that hyperbolic discounters often fail to follow through on plans, how could you structure the loans to ensure payment? Use the quasi-hyperbolic model to make your argument.

(b)The absolute-magnitude effect suggests that people are much closer to time consistency with regard to larger amounts. How might this explain the difference in the structure of consumer credit (or shortterm loans) and banks that make larger loans?

(c)Lotteries often offer winners an option of receiving either an annual payment of a relatively small amount that adds up to the full prize over a number of years or a one-time payment at a steep discount. Describe how time inconsistency might affect a

R E F E R E N C E S

lottery winner’s decision. How might the lottery winner view her decision after the passage of time?

4.Harper is spending a three-day weekend at a beach property. Upon arrival, Harper bought a quart of ice cream and must divide consumption of the quart over

each of the three days. Her instantaneous utility of ice cream consumption is given by U c

c = c0.5, where c is measured in quarts, so that the instantaneous marginal utility is given by 0.5c− 0.5.

= c0.5, where c is measured in quarts, so that the instantaneous marginal utility is given by 0.5c− 0.5.

(a)Suppose Harper discounts future consumption

according to the fully additive model, with the daily discount factor δ = 0.8. Solve for the optimal

consumption plan over the course of the three days by finding the amounts that equate the discounted marginal utility of consumption for each of the three days, with the amounts summing to 1.

(b)Now suppose that Harper discounts future utility

according to the quasi-hyperbolic discounting model, with β = 0.5, and δ = 0.8. Describe the

optimal consumption plan as of the first day of the weekend. How will the consumption plan change on day two and day three?

(c)The model thus far eliminates the possibility that Harper will purchase more ice cream. In reality, if consumption on the last day is too low, Harper might begin to consider another ice cream purchase. Discuss the overall impact of hyperbolic discounting on food consumption or on the consumption of other limited resources.

5. Consider |

the diet problem of |

Example |

12.3. |

Let |

δ = 0.99, |

ul = 2, uh = 1, γi = 1 |

180 for |

all i, |

and |

w = 140. Suppose that initial weight in the first period is 200. How high does β need to be before the person will actually go on a diet rather than just planning to in the future? Use geometric series to solve this analytically.

Ainslie, G.W. Picoeconomics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press, 1992.

Benzion, U., A. Rapoport, and J. Yagil. “Discount Rates Inferred from Decisions: An Experimental Study.” Management Science

35(1989): 270–284.

Bishop, J.A., J.P. Formby, and L.A. Zeager. “The Effect of Food Stamp Cashout on Undernutrition.” Economic Letters 67(2000): 75–85.

Loewenstein, G. “Anticipation and the Valuation of Delayed Consumption.” Economic Journal 97(1987): 666–684.

|

|

|

|

|

346 |

|

NAÏVE PROCRASTINATION |

Loewenstein, G. “Frames of Mind in Intertemporal Choice.”

Management Science 34(1988): 200–214.

Loewenstein, G., and D. Prelec. “Anomalies in Intertemporal Choice: Evidence and an Interpretation.” Quarterly Journal of Economics

107(1992): 573–597.

Odum, A.L., G.J. Madden, and W.K. Bickel. “Discounting of Delayed Health Gains and Losses by Current, Neverand Ex-Smokers of Cigarettes.” Nicotine & Tobacco Research 4 (2002): 295–303.

Strotz, R.H. “Myopia and Inconsistency in Dynamic Utility Maximization.” Review of Economic Studies 23(1955-56): 165–180.

Thaler, R.H. “Some Empirical Evidence on Dynamic Inconsistency.”

Economics Letters 8(1981): 201–207.

Wilde, P.E., and C.K. Ranney. “The Monthly Food Stamp Cycle: Shopping Frequency and Food Intake Decisions in an Endogenous Switching Regression Framework.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 82(2000): 200–213.

|

|

|

Committing and Uncommitting |

|

|

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The story of procrastination due to hyperbolic discounting is an intriguing one, but it seems to require the procrastinator to be rather dim—or in the words of economists, “naïve.” Owing to hyperbolic discounting, people might realize that they should go on a diet but put off the diet until tomorrow given the steep discount they give to utility of consumption the next day. But when tomorrow arrives, that steep discount is applied to the next day, resulting in putting off the diet one more day. Exactly how many days in a row can people put off their diet before they realize their behavior is preventing them from achieving their goal? Similarly, how often can one put off studying until the last day before the exam without noticing how the behavior affects one’s performance? And if the decision maker does start to recognize the problem of time inconsistency, what would his reaction be?

Consider first the would-be dieter. After several days of wanting to go on a diet, but putting it off “just this once,” the dieter might realize “just this once” has become an eternal excuse. What he needs is some way to enforce his current preferences on his future self. The dieter might then race through the kitchen and decide to throw away all foods that would tempt him to break his diet tomorrow. Ice cream and cookies are thrown out, with maybe a few eaten along the way, so that tomorrow the dieter will not be able to break his diet except through extreme exertion—enough exertion that it would not be attractive even to a hyperbolic discounter. If the would-be dieter can make the cost of breaking his plan high enough, he will implement the plan, obtaining the long-term goal at the expense of the short-term splurge.

Commitment mechanisms are ubiquitous in our economic lives. Some might exist as a way to allow actors to assure others that they are negotiating in good faith, such as a contract for labor, but others seem incompatible with the rational model of decision making. Commitment mechanisms reduce the set of possible choices available in the future. In all cases, a rational decision maker would consider a reduction in the choice set to be something that at best leaves the decision maker no better off. But then, no rational decision maker would ever consider paying to engage in a commitment mechanism. Consider the familiar story of Odysseus, who with his crew must sail past the Sirens. He is warned by Circe that the Sirens’ song is irresistible and that all who hear it are led unwittingly to an ignominious death as their boat is wrecked on the jagged rocks near the island. No sailor has ever escaped their temptation, even though he might have known of the legend.

Odysseus commands his men to fill their ears with wax so that they cannot hear the song and thus cannot be tempted, though they would still have the choice of where to steer the ship.

347