- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

Thought Questions |

|

307 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Biographical Note

Bloomberg / Getty Images

Dan Ariely (1967–)

M.A. University of North Carolina, 1994; Ph.D.,

University of North Carolina, 1996; Ph.D., Duke

University, 1998; held faculty positions at

Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Duke

University

Dan Ariely was born in New York, though he spent most of his time growing up in Israel. He studied philosophy as an undergraduate at Tel Aviv University and later obtained his master’s and Ph.D. degrees in cognitive psychology, with an additional Ph.D. in business

administration. He attributes his interest in irrational behavior to a horrifying experience in his senior year of high school. While volunteering with a youth group, he was engulfed in an explosion, suffering severe burns over 70 percent of his body. In recovering from this, he began to notice the behavioral strategies he used to deal with painful treatments and the general change in the course of his life. His research is wide ranging, including experiments that examine how people use arbitrary numbers from their environment (including their Social Security number) to formulate a response to questions about how much an item is worth to them and how people value beauty and cheating behavior. He is also well known for his popular books

Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape our Decisions and The Upside of Irrationality: The Unexpected Benefits of Defying Logic at Work and at Home.

T H O U G H T Q U E S T I O N S

1.Projection bias causes people to suppose that dialysis patients have a much lower quality of life than actually

prevails. However, when prompted by researchers to think about the ways they will adapt their lives to dialysis, people seem to make much more realistic assessments. Researchers also find that people several years after winning the lottery rate their quality of life about the same as those who through an accident had become quadriplegic (losing the use of their arms and legs) at about the same time. Relate this phenomenon to projection bias. How might projection bias affect people’s choice to play the lottery? What might this say about get-rich-quick schemes in general? How might we think about correcting projection bias in this case?

2.To a large extent, one’s lifestyle and the options available to one depend on choices made while

relatively young: occupation, place of residence, and perhaps even long-term relationships. Suppose that for leisure, people can either choose quiet evenings with friends, cq, or raucous parties, cp. Suppose that when

young, |

sy, people |

strongly prefer raucous |

parties, |

|

u |

cp sy |

= 2, u cq sy |

= 1. Alternatively, when old, so, |

|

people |

strongly prefer quiet times with |

friends, |

||

u |

cp so |

= 1, u cq so = 3. Suppose that Chandra is |

||

choosing between majoring in business finance or recreation management. Both majors require just as much time and effort now and offer the same current opportunities for leisure. However, when old, those who majored in finance will only be able to engage in quiet time with friends (raucous parties could get you fired), whereas those in recreation management will only have access to raucous parties. Use the simple

|

|

|

|

|

308 |

|

DISAGREEING WITH OURSELVES: PROJECTION AND HINDSIGHT BIASES |

projection bias model to discuss what Chandra will choose. What degree of bias is required before Chandra chooses to enter recreation management? What advice might this suggest to students in general?

3.Suppose that Marion is considering smoking the first cigarette. Marion’s utility of consumption in the cur-

rent period is given by equation 11.12, where good c is cigarettes, good f is all other consumption, γ1 = 4, γ2 = 1, and γ3 = 2, and xc, 0 = 0. Suppose the price of a unit of consumption for either good is $1 and that Marion has $10. Calculate Marion’s optimal consumption given one future period of choice in which he has an additional $10. Now suppose that Marion suffers from simple projection bias. Calculate the consumption he will choose as a function of α. What impact will projection bias have on his realized utility? Formulas in equations 11.13 to 11.22 may be useful in making these calculations.

4.Researchers have found that people who are hungry tend to have greater craving for food that is more indulgent (i.e., high in sugar, fat, and salt). Consider that you are creating a line of convenience foods— either snack foods or frozen foods.

(a)Describe the circumstances under which most people decide to eat convenience foods. What state are they likely to be in? Given this, what types of convenience foods are most likely to be eaten?

R E F E R E N C E S

Camerer, C., G. Loewenstein, and M. Weber. “The Curse of Knowledge in Economic Settings: An Experimental Analysis.”

Journal of Political Economy 97(1989): 1232–1254.

Conlin, M., T. O’Donoghue, and T.J. Vogelsang. “Projection Bias in Catalog Orders.” American Economic Review 97(2007): 1217–1249.

Fischhoff, B. “Hindsight  Foresight: The Effect of Outcome Knowledge on Judgment Under Uncertainty.” Journal of Exper-

Foresight: The Effect of Outcome Knowledge on Judgment Under Uncertainty.” Journal of Exper-

imental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 1 (1975): 288–299.

Gilbert, D.T., M.J. Gill, and T.D. Wilson. “The Future is Now: Temporal Correction in Affective Forecasting.” Organiza-

tional Behavior and Human Decision Processes 88(2002): 430–444.

Loewenstein, G. “Emotions in Economic Theory and Economic Behavior.” American Economic Review 90(2000): 426–432.

(b)Consider now that most foods are purchased long before they are eaten, though most people only purchase items that they use. In what state are shoppers more likely to purchase convenience foods? Does this depend on whether convenience foods are healthy or indulgent?

(c)Create a simple model of food choice based on simple projection bias. What food would a seller choose to sell to maximize profits, and how does this depend on α?

(d)Describe your strategy for creating a line of convenience foods. Is there any way to create a successful line of healthy convenience foods?

5.Employers are constantly training new employees by using more-experienced employees as instructors.

(a)What challenges might the curse of knowledge present in the training process? How might you suggest these challenges could be overcome?

(b)Often new employees are given a short (but inadequate) training course and then afterward are given a mentor whom they follow for a brief period before being allowed to function fully on their own. Employers tend to use the same mentor repeatedly rather than using a different one each time. What might this suggest about the curse of knowledge and how it could be addressed?

Loewenstein, G., T. O’Donoghue, and M. Rabin. “Projection Bias in Predicting Future Utility.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (2003): 1209–1248.

Mandel, G.N. “Patently Non-Obvious: Empirical Demonstration that the Hindsight Bias Renders Patent Decisions Irrational.” Ohio State Law Journal 67(2006): 1393–1461.

Read, D., and B. van Leeuwen. “Predicting Hunger: The Effects of Appetite and Delay on Choice.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 76(1998): 189–205.

Sacket, D.L., and G.W. Torrance. “The Utility of Different Health States as Perceived by the General Public.” Journal of Chronic Disease 31(1978): 697–704.

Ubel, P.A., G. Loewenstein, and C. Jepson. “Disability and Sunshine: Can Hedonic Predictions be Improved by Drawing Attention to Focusing Illusions or Emotional Adaptation?” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 11(2005): 111–123.

Naïve Procrastination

12

Except for a very select few, almost all federal taxpayers have the necessary materials in their hands to file their federal taxes by the middle of February. Nonetheless, every year, 40 million people in the United States wait until the week of April 15th (the federal deadline) to file their tax returns. This is just about a quarter of all tax returns filed in the United States. Most post offices remain open until midnight on April 15th just for this special class of procrastinators. Many of these procrastinators eventually receive tax refunds, and some refunds are substantial.

Waiting until the last minute can create a risk of missing the deadline. Those filing electronically might have their returns rejected for missing information or other errors. Sometimes communication lines go down in the waning hours of the 15th, overloaded by too many choosing to file at the same time. Those filing by mail often run into very long lines at the post office and risk missing the last opportunity to file. Moreover, putting off preparing taxes until the very last minute can create problems as taxpayers only realize that certain receipts or documents are missing once they have begun to fill out the forms. Ultimately, missing the deadline can result in financial penalties. So why do so many procrastinate until the last minute?

As teenagers and young adults we are bombarded with the advice to “never put off until tomorrow what you can do today.” Nonetheless, procrastination seems to be engrained into human behavior from our earliest opportunities to make decisions. We put off studying until we are forced to cram all night for the big test. We put off cleaning, maintenance, or other work until we are forced into action. Then we must complete tremendous amounts of work in a very short time. Procrastination becomes a problem when we prioritize activities that are not particularly important over those that have real and if not immediate at least long-term consequences. After one has been burned time after time by failing to study early or after a steady stream of financial emergencies that could not be covered by a meager savings, it would seem like time to stop procrastinating. A quotation attributed to Abraham Lincoln is, “Things may come to those who wait, but only the things left by those who hustle.” If that is so, why do we seem so apt to procrastinate? Some economists believe the answer lies in how we value today versus tomorrow versus the day after tomorrow.

Procrastination, like the hot–cold empathy gap described in Chapter 11, can result in timeinconsistent preferences. We might see others who went to work right away, look back on our actions, and consider that we have taken the wrong strategy. Firms interested in selling products can use customer procrastination to their own advantage through price discrimination or by

309

|

|

|

|

|

310 |

|

NAÏVE PROCRASTINATION |

charging customers for services or the option to take some action that they will never exercise. In some cases, finding last-minute tax preparation is more costly than early preparation. In others, people might pay in advance for flexible tickets that they never actually find the time to use. This chapter introduces the exponential model of time discounting, the most common in economic models, and the quasi-hyperbolic model of time discounting. The latter has become one of the primary workhorses of behavioral economics. This model is expanded on in Chapter 13, where we discuss the role of people’s understanding and anticipation of their own propensity to procrastinate.

The Fully Additive Model

In Chapter 11, we introduced a general model of intertemporal choice when the consumer is deciding on consumption in two different time periods. In many cases that we are interested in, a consumer considers more than just two time periods. In some cases we are interested in planning into the distant future. This is often represented as a problem involving an infinite number of time periods, or an infinite planning horizon. We can generalize the model presented in equation 11.1 to the many-period decision task by supposing the consumer solves

maxc1, c2, U c1, c2, |

12 1 |

subject to some budget constraint, where ci represents consumption in period i. This model is general in the behavior that it might explain because it allows every period’s consumption to interact with preferences for every other period’s consumption. Thus, consuming a lot in period 100 could increase the preference for consumption in period 47. This model is seldom used specifically because of its generality. We tend to believe people have somewhat similar preferences for consumption in each period. Moreover, we often deal with situations in which consumption in one period does not affect preferences in any other period. Thus, when dealing with intertemporal choice with many periods, economists tend to prefer the fully additive model, assuming exponential discounting. This model assumes that

U c1, c2, |

= u c1 + δu c2 + δ2u c3 + + δi − 1u ci + = |

T |

δi − 1u ci |

, |

|

i = 1 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

12 2 |

||

where δ represents how the person discounts consumption one period into the future and where T could be  .

.

The fully additive model is based upon two fundamental assumptions. First, the consumer has stable preferences over consumption in each period. Thus, u ci

ci can be used to represent the benefit from consumption in each time period i, often referred to as the instantaneous utility function. This may be more important in the case where u

can be used to represent the benefit from consumption in each time period i, often referred to as the instantaneous utility function. This may be more important in the case where u .

. has several arguments. For example, suppose that u

has several arguments. For example, suppose that u ci

ci = u

= u c1, i, c2, i

c1, i, c2, i , where c1, i represents hours spent studying at time period i, and c2, i represents hours spent partying at time period i. Then the additive model assumes that the same function will

, where c1, i represents hours spent studying at time period i, and c2, i represents hours spent partying at time period i. Then the additive model assumes that the same function will

|

|

|

|

The Fully Additive Model |

|

311 |

|

describe the utility tradeoffs between partying and studying in every time period. Thus, whether you are three weeks from the test or one hour from the test, the student still has the same relative preference for studying and partying. Second, the consumer discounts each additional time period by a factor of δ, referred to as exponential time discounting. Consuming c next period will yield exactly δ times the utility of consuming c now. Moreover, consuming c two periods from now will yield exactly δ times the utility of consuming c next period, or δ2 times the amount of utility of consuming c this period. This coefficient δ, often referred to as the discount factor, may be thought of as a measure of patience. The higher the discount factor, the more the consumer values future consumption relative to current consumption and the more willing the consumer will be to wait.

The solution to a problem such as that in equation 12.2 occurs where the discounted marginal utility of consumption in each period is equal, δi − 1u′ ci

ci = k, where u′

= k, where u′ c

c is the marginal utility of consumption (or the slope of the instantaneous utility function), and k is some constant. Intuitively, if one period allowed a higher discounted marginal utility than the others, consumers could be made better off by reducing consumption in all other periods in order to increase consumption in the higher marginal utility period. Similarly, if marginal utility of consumption in any period was lower than the others, consumers would benefit by reducing their consumption in that period in order to increase consumption in a higher marginal utility period. This would continue until marginal utility equalizes in all periods. Thus, given the instantaneous marginal utility of consumption function, you can solve for the optimal consumption profile by finding the values for ci such that δi − 1u′

is the marginal utility of consumption (or the slope of the instantaneous utility function), and k is some constant. Intuitively, if one period allowed a higher discounted marginal utility than the others, consumers could be made better off by reducing consumption in all other periods in order to increase consumption in the higher marginal utility period. Similarly, if marginal utility of consumption in any period was lower than the others, consumers would benefit by reducing their consumption in that period in order to increase consumption in a higher marginal utility period. This would continue until marginal utility equalizes in all periods. Thus, given the instantaneous marginal utility of consumption function, you can solve for the optimal consumption profile by finding the values for ci such that δi − 1u′ ci

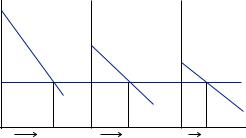

ci = k for some k and such that all budget constraints are met. One way to picture this optimum is displayed in Figure 12.1. On each vertical axis is displayed the discounted marginal utility of consumption for one time period. Overall utility is optimized where consumption in each period yields the same level of discounted marginal utility (depicted by the horizontal line). The discount causes each successive curve to be less steep and to be scaled in toward the x axis by the discount factor. This results in declining consumption in each period.

= k for some k and such that all budget constraints are met. One way to picture this optimum is displayed in Figure 12.1. On each vertical axis is displayed the discounted marginal utility of consumption for one time period. Overall utility is optimized where consumption in each period yields the same level of discounted marginal utility (depicted by the horizontal line). The discount causes each successive curve to be less steep and to be scaled in toward the x axis by the discount factor. This results in declining consumption in each period.

Let us see how we can use this model to examine a simple choice. Suppose a decision maker is given a choice between consuming some extra now or a lot extra later. Suppose that to begin with a decision maker consumes c each period. Then, in addition to c, the decision maker is given the choice of consuming an additional x at time t or an additional

x′ > x at time t′ > t. The decision maker will choose x at time t if the additional utility of doing so,  i

i tδiu

tδiu c

c + δtu

+ δtu c + x

c + x >

> i

i t′δiu

t′δiu c

c + δt′u

+ δt′u c + x′

c + x′ , where the right side of

, where the right side of

utility |

u'(c1) |

|

δu'(c2) |

|

δ2u'(c3) |

Discounted marginal |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

c1 |

c1 |

c2 |

c2 |

c3 |

c3 |

FIGURE 12.1

Optimal Consumption with More than Two Periods