- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect |

|

85 |

|

Thus, if the person had x2* of good 2, and was given p1WTA p2 more of good 2, his utility |

|

|

|

from good 2 would be increased by the quantity u1. If the utility for good 2 displays |

|

|

|

diminishing marginal utility, it must require a larger increase in the amount of good 2 to |

|

|

|

increase utility by u1 than a loss to reduce utility by u1. Thus, diminishing marginal |

|

|

|

utility of good 2 would imply that p1WTP p2 < p1WTA p2, or p1WTP < p1WTA. This is due to |

|

|

|

the wealth effect. Endowing the person with a unit of good 1 increases the person’s |

|

|

|

overall resources, changing the marginal utility of each good and thus the worth of the |

|

|

|

good. However, if the value of good 1 is small relative to overall wealth, we would |

|

|

|

expect this wealth effect to be small. Over smaller changes in wealth, the effect of |

|

|

|

diminishing marginal utility must also be small, and the utility function could be |

|

|

|

approximated by a straight line. One of the foundational notions behind the development |

|

|

|

of calculus is that continuous and smooth functions can be approximated by a line over |

|

|

|

small changes in the domain. If the utility for good 2 in this example were a straight line, |

|

|

|

then p1WTP p2 = p1WTA p2. Thus, if the value of good 1 is small, we may suppose that |

|

|

|

p1WTP p1WTA. For example, we would expect virtually no wealth effect from a small |

|

|

|

gift such as a coffee mug, which should then feature almost identical values for WTP |

|

|

|

and WTA. |

|

|

|

Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

Because a gain of a particular value results in a smaller change in utility than a corresponding loss, loss aversion predicts that a good will take on a different value before and after it is incorporated into the reference point. Thus, a good that might be purchased may be evaluated as a potential gain, whereas a good that has been purchased will eventually be incorporated into the reference point. Once the good is incorporated into the reference point, parting with the good would be considered a loss. Hence, loss aversion predicts that the amount one is willing to pay to acquire a good should be substantially less than the amount the person is willing to accept to part with the good once it is incorporated into the reference point. This effect is called the endowment effect.

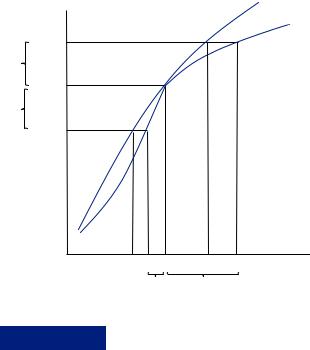

As noted previously, measures of willingness to pay and willingness to accept should always be the same if the utility of consumption for both can be represented by a straight line. Further, the measures should be similar if the utility function can be approximated by a line over the change in wealth induced by endowing the person with a good. Loss aversion suggests that no matter how small the change in wealth, we cannot approximate the utility function using a line. This is because the function is kinked at the reference point, x2*, with a steeper slope below this point and a shallower slope above, as pictured in Figure 4.6. Figure 4.6 depicts both a kinked and a standard utility function that are equal at the reference point. Note that under this condition, the WTP is necessarily smaller with the kinked curve, and WTA is necessarily larger under the kinked curve. This means that even for small changes in wealth, the utility function will behave as if it is concave. Thus, even for very small changes in wealth, we should observe pWTP1 < pWTA1 , suggesting substantial differences between willingness to accept and willingness to pay.

|

|

|

|

|

86 |

|

STATUS QUO BIAS AND DEFAULT OPTIONS |

u2

2 (~2*) u x

∆u1

u2 (x2*)

∆u1

u2 (xˆ2*)

FIGURE 4.6

Loss Aversion and the Disparity between Willingness to Pay (WTP)

and Willingness to Accept (WTA)

ˆ |

x2* |

~ |

x2 |

x2* |

x2* |

||

p1WTP / p2 |

p1WTA/ p2 |

|

|

EXAMPLE 4.7 Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler designed a series of experiments to test for the endowment effect predicted by loss aversion. To test this, they needed to use an item of relatively small value so that willingness to pay and willingness to accept would be similar for any rational decision maker. In one of these experiments, several participants were brought to a room. Half of them were given a mug, and the other half were not. The participants were told that they would have the opportunity to buy or sell mugs in a market. Those who had been given a mug were asked for the minimum amount of money they would be willing to take in return for the mug. This information was used to determine a supply schedule for mugs. Those who had not been given a mug were asked to report the maximum amount they would be willing to pay for the mug. This information was used to determine a demand schedule for mugs. A price was determined by the intersection of the supply and demand schedules derived from the participants.

All those willing to pay more than the price determined by the market received a mug in exchange for that price, and all those willing to accept less than that price sold their mug for that price. The median willingness to accept was $5.25, and the median willingness to pay was only around $2.25. Referring again to Figure 4.5, this would require that the marginal utility above x2* be roughly half of the marginal utility below. Further, this requires that over the course of a change in wealth of $2.25 + $5.25 = $7.50, the marginal utility of wealth must decline by more than 50 percent! Similar responses were obtained when using pens, a good with even smaller value.

This suggests that the utility function truly is kinked near the reference point, as proposed by prospect theory. Further, this experiment seems to suggest that goods are incorporated immediately upon receipt into the reference point. Thus, individual

|

|

|

|

Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect |

|

87 |

|

preferences can change very rapidly in response to gifts or other similar changes in endowment. Finally, these experiments were performed several times with the same participants with very similar results in each round. This suggests that such behavior is likely to persist in a marketplace, unlike many less-than-rational behaviors. The effect in a market should be to reduce the number of transactions that can take place because those who own value a good more highly than those who don’t.

EXAMPLE 4.8 Money-Back Guarantees and Free Trials

Many stores in the United States offer money-back guarantees for their products. These guarantees allow a consumer to return an item to the store for a refund if they discover they do not like the good as much as they thought they would. Many stores require that the good must be returned in 30 days, but some stores even offer lifetime money-back guarantees. Why might a store be willing to offer a money-back guarantee? First, consumers might face some uncertainty about the product they are buying. For example, consumers might feel that a clothing item fits and seems to complement their existing wardrobe while they are in the store, but they worry that they will feel differently at home. Or, they may be uncertain whether an electronics item is compatible with their other equipment. The money-back guarantee offers the consumer some insurance, limiting the risk from purchase. Thus, the money-back guarantee adds value to the good before purchase and experience with the good, encouraging sales. Second, once the good is purchased it takes on additional value owing to the endowment effect. Thus, before the purchase customers might believe that they would return an incompatible piece of electronic equipment, but once they purchase it they would consider a return a loss. Thus, they might keep the item and potentially purchase other items to make their original purchase more useful. The money-back guarantee lowers the threshold of value the consumer must expect the good to hold in order to purchase, and it raises the threshold of value the consumer must have for the good in order to return the item. Thus, the money-back guarantee is likely to improve the profits of the retailer.

A related marketing technique is the free trial. Much like the money-back guarantee, the free trial offers the customer the opportunity to own the good for a time at no expense. After the period of the free trial, the customer must decide whether to pay for the good or return it. The endowment effect suggests that once customers own the good, they will be less willing to part with it. Thus, the marketer will be able to demand a higher price than if the good were purchased before a trial.

Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

Several potential rational explanations have been given for the endowment effect. One explanation is that people face uncertainty about the value of the good before obtaining the item. Thus, when deciding on a willingness to pay, I might believe the item is worth as much as $7 or as little as $2, but on average I feel it is worth $4. In this case, I might only be willing to pay $3, less than what I feel the average guess at the price would be, owing to my uncertainty. On the other hand, if I were given an item and became certain of its value,

|

|

|

|

|

88 |

|

STATUS QUO BIAS AND DEFAULT OPTIONS |

I would be willing to accept that value in return. Thus, if the value is $4, my willingness to pay is greater than my willingness to accept for the good. However, many have pointed out that mugs and pens are relatively known quantities. Thus it may be difficult to imagine that there is substantial uncertainty regarding the value of these items.

Further, there are questions as to whether the endowment effect really persists. John List ran a set of experiments by setting up markets for trading candy bars and mugs at a sports trading card exhibition. He found evidence of the endowment effect when market participants were amateur sports card collectors, but the endowment effect disappeared when the market participants were sports card dealers. He suggests that the sports card dealers have intense experience with trading markets owing to their trade in sports cards. Thus, it may be that the endowment effect is eliminated when the participant is familiar enough with markets and trading environments. Interestingly, this experience is not exclusive to the market the person usually participates in. Presumably the sports card dealers had little experience in selling and trading mugs or candy bars.

History and Notes

The term “endowment effect” was coined by Thaler in his 1980 paper describing various anomalies in consumer behavior. This effect soon drew the attention of environmental and resource economists. Economists studying issues involving environmental policy often need to find a value for goods that cannot be traded in the market. Thus, they might need to determine the value to local consumers of a new mall in order to determine if it is worth the environmental costs. Potential consumers could be asked their willingness to pay for the new mall. Alternatively, those who own homes very near the site might lose a spectacular view when the mall goes up, as well as needing to deal with added traffic, noise, and bright lights at all hours of the night. These people may be asked their willingness to accept these inconveniences. Then the economist could determine whether the mall would improve or decrease welfare by examining whether those who want the mall could potentially pay those who do not want it enough to compensate them. Early on it had been noted that willingness-to-accept responses seemed to be inflated relative to willing- ness-to-pay measures. This led Jack Knetsch, a trained environmental and resource economist, to begin investigating the endowment effect on an experimental basis in a series of papers culminating in his work with Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler. Knetsch’s work confirmed that indifference curves appear to cross in experiments and that differences in willingness to pay and willingness to accept seem disproportionate to the changes in wealth that are taking place. The endowment effect calls into question many of the techniques that have been used to determine the value of environmental goods—a fruitful field for application of behavioral economic models.