- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

|

144 |

|

BRACKETING DECISIONS |

Bracketing and Variety

It appears that when people bracket broadly, the person values variety much more than when bracketing narrowly. This might not be too surprising, because one has a much more difficult time identifying variety in a single item. This is a property that only emerges when choices are grouped together. The question then arises: Who is better off? Generally we regard people who have made broadly bracketed decisions as better off because they are able to account for how one decision influences the other. But it is possible that it works the other way. In this case, it may be that the broadly bracketed decisions anticipate valuing variety much more than they truly will. Remember that these food choices were made a week apart. If one were eating the same thing every day, monotony might lead you away from your favorite food after a short period. But if you chose to eat the same thing every Friday, there is plenty of room for variety in the intervening six days. Thus, people might display a diversification bias.

This has been evident in many different contexts. For example, people tend to spread their retirement investments equally among all possible options in a retirement program, even if some are relatively unattractive. In this case, people seek variety when broadly bracketing choices, even if it might make them worse off when consumption takes place. The type of diversity sought might have much to do with the framing of the decision. For example, suppose a tourist is visiting a new city for a week and is deciding where to eat that week. If presented with a list of restaurants divided into categories by the type of food they serve, the diner may be led to choose one traditional American restaurant, one Chinese restaurant, one Italian, and so on. Alternatively, if she is presented a list divided into regions in the city, she might choose to eat in a different location each day.

Rational Bracketing for Variety

Simonson explains the results of his study by suggesting that people might simply be uncertain of their future preferences for individual snacks, and thus they seek variety as a means of diversifying the outcome and maximizing expected utility. Read and Loewenstein sought to test this hypothesis. If one is unsure of one’s preferences, then one should not be able to predict one’s subsequent choices with accuracy. In fact, when students were asked to predict what they would choose in sequential choice, they were highly accurate, with virtually no difference. Further, those in the simultaneous choice condition predicted that they would seek less variety if they were to choose sequentially. It appears that at some level people are aware of how bracketing influences variety seeking. Nonetheless, the degree of accuracy of predictions seems contrary to the notion that people are uncertain of their future preferences for the items.

EXAMPLE 6.5 Cigarette Addiction

Cigarettes, and other items containing powerful drugs, are extremely addicting. These items provide some immediate pleasure or high, making them highly attractive at any one point in time. However, the drugs in the cigarettes have a diminishing effect on the body as the smoker builds up a resistance to the drug. Thus, someone who has been smoking

|

|

|

|

Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing |

|

145 |

|

for years does not get the same high or pleasure from the nicotine in a single cigarette that a new smoker receives. How then can it be addicting? Generally, we believe that diminishing marginal utility of use leads to cessation of consumption. For example, pizza displays diminishing marginal utility of use. Thus, I receive less enjoyment from the third slice than from the first slice. When the enjoyment is low enough, it is no longer worth the effort to eat it, and I stop eating. Suppose I tried eating pizza for every meal. Eventually, I would grow tired of the monotony as my marginal utility of pizza diminished, and I would start eating some other food instead. How are cigarettes different?

Consider the alternative activities that one could engage in. Suppose, for example, the only other alternatives to smoking were to play sports. Smoking may reduce the pleasure from playing sports. It becomes more difficult to breathe or run when one smokes on a regular basis. More generally, doing anything for long periods that is incompatible with smoking may be made unpleasant if feelings of withdrawal kick in. If, in fact, smoking reduces the pleasure from alternative activities more than it decreases the pleasure from smoking, the smoker might face an ever-increasing urge to smoke because everything else looks less attractive by comparison. In fact, smoking and other drug use has been shown to have strongly negative effects on the pleasure one derives from other activities. If this were true, why would one then choose to smoke if it reduces future pleasure from all activities?

Bracketing may play a role. At any one time, a smoker might consider the high of smoking and perhaps other immediate social advantages. But narrowly bracketing the choice to the single cigarette ignores the future impact of the cigarette on the utility of all future activities. Thus, narrow bracketing could lead to melioration: a focus on the now at the expense of long-term goals. Many smokers when asked would like to quit being smokers. Nonetheless, very few would turn down their next cigarette.

Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice

Bracketing

Richard Hernstein and several colleagues propose a simple model of melioration in this context. Suppose that the consumer may choose between two consumption items in each of two decision periods: cigarettes, x, and other consumption goods, y. Suppose that consumption of cigarettes influences the utility of consuming either cigarettes or other goods in the second period, but doing other activities has no impact on future utility. The consumer’s rational decision problem can be written as

max u1 x1, y1 + u2 x2, y2, x1 , |

6 24 |

x1,x2,y1y2 |

|

subject to the budget constraint

px x1 + x2 + py y1 + y2 ≤ w. |

6 25 |

Here, u1 x1, y1

x1, y1 is the utility of consumption in the first period as a function of cigarette consumption and other activities in that period, u2

is the utility of consumption in the first period as a function of cigarette consumption and other activities in that period, u2 x2, y2, x1

x2, y2, x1 is the utility of consumption in the second period as a function of cigarettes consumed in both periods and other consumption in the second period, w is the total budget for consumption in both periods,

is the utility of consumption in the second period as a function of cigarettes consumed in both periods and other consumption in the second period, w is the total budget for consumption in both periods,

|

|

|

|

|

146 |

|

BRACKETING DECISIONS |

and p1 and p2 are the prices of cigarette and other consumption, respectively. But, under melioration, the consumer does not consider the impact of the first period consumption of cigarettes on the second period consumption of either cigarettes or other goods. Thus, the consumer would bracket narrowly and behave as if she were to solve

max u1 x1, y1 |

+ max u2 x2, y2, x1 |

6 26 |

x1, y1 |

x2, y2 |

|

subject to the budget constraint in equation 6.25. A decision maker solving equation 6.26 will ignore all future consequences of her consumption in period 1 and pay the price for her naïveté in period 2.

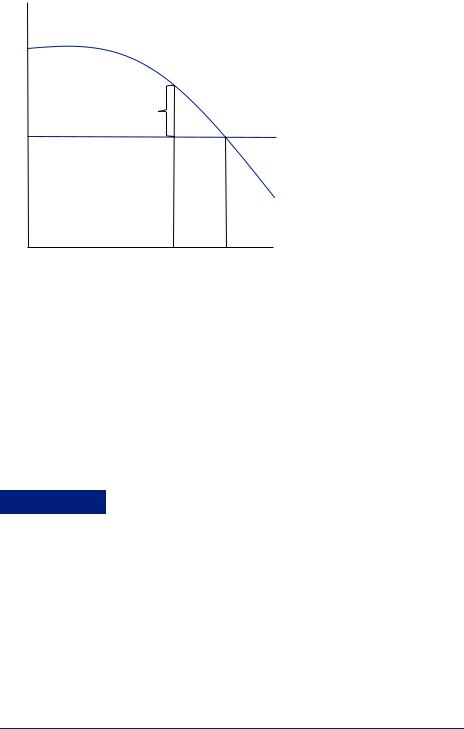

The condition for the solution to equation 6.26 finds the point where marginal utility of consumption divided by the price of consumption is equal for cigarettes and other consumption in the first period. But this ignores the added cost that cigarettes impose on future consumption. If cigarettes reduce the utility of consumption in the future, then this cost should also be considered. Thus, the proper solution to equation 6.24 equates the marginal utility of cigarette consumption in period 1 plus the marginal impact of period 1 consumption of cigarettes on period 2 utility, all divided by the price of consumption with the marginal utility of consumption of other items divided by their price. By ignoring this cost in terms of future utility, the smoker consumes more cigarettes in the first period than would be optimal. Further, if cigarettes make consumption of cigarettes relatively more attractive in the second period than other goods, it leads to greater-than- optimal consumption of cigarettes in the second period also.

Suppose that both goods had the same price. Then, the smoker displaying melioration would equate marginal utility across cigarettes and other consumption in the first period. Let us further suppose that utility in the first period is additive and that the smoker receives constant marginal utility from consumption of other goods, u1 x1, y1

x1, y1 = ux1

= ux1 x1

x1 + ky1. Then we can represent the problem as in Figure 6.5. Here, if the smoker displays melioration, she will set the marginal utility of cigarettes in period 1, u′x1, equal to marginal utility of other goods in period 1, k = u′y1, obtaining xM1 . Optimally, she should set the sum of marginal utilities from cigarettes over both periods equal to the marginal utility of other goods. That is, the marginal utility of cigarettes in period 1, u′x1 plus the marginal utility in period 2 of cigarettes consumed in period 1, u′x2 should be set equal to k. If the marginal utility in the second period is negative, then the optimal consumption of cigarettes will be above the melioration optimum. If on the other hand the marginal utility in the second period is positive, then the melioration optimum will be below the true optimum. In this case, narrow bracketing could lead to addictive behaviors where one does not consider the future costs of one’s actions.

+ ky1. Then we can represent the problem as in Figure 6.5. Here, if the smoker displays melioration, she will set the marginal utility of cigarettes in period 1, u′x1, equal to marginal utility of other goods in period 1, k = u′y1, obtaining xM1 . Optimally, she should set the sum of marginal utilities from cigarettes over both periods equal to the marginal utility of other goods. That is, the marginal utility of cigarettes in period 1, u′x1 plus the marginal utility in period 2 of cigarettes consumed in period 1, u′x2 should be set equal to k. If the marginal utility in the second period is negative, then the optimal consumption of cigarettes will be above the melioration optimum. If on the other hand the marginal utility in the second period is positive, then the melioration optimum will be below the true optimum. In this case, narrow bracketing could lead to addictive behaviors where one does not consider the future costs of one’s actions.

Addiction and Melioration

One can imagine a series of choices between action x and action y. In the first period, choosing x returns a utility of 10, and choosing y returns a utility of 7. But playing x reduces the utility of playing x in the next period by 1 and reduces the utility of playing y in the following period by 2. Thus, if one chooses x in the first period, in the second

|

|

|

|

Addiction and Melioration |

|

147 |

|

ui1 (.)

u2 '(x1) |

|

|

|

k |

|

uy1 '(y1) |

|

|

|

ux1'(x1) |

|

x1* |

|

|

FIGURE 6.5 |

x1M |

x1 |

Melioration in the Cigarette Problem |

period one could choose x and obtain 9 or could choose y and obtain 5. Someone who does not discount future periods playing any more than 7 periods of this choice should choose to play y in the first period, and continue playing y until she reaches the seventh period from the end of the game, when the reduction in future utility ceases to be important. On the other hand, once one has played x, y becomes less and less attractive. Thus, a narrowly bracketed decision to play x on a repeated basis could lead to a state in which broadly bracketed decisions also lead to choosing x. This paints the picture of addiction as a slippery slope, where unsuspecting and perhaps naïve people fall prey to a few bad decisions. However, those decisions recreate the incentives in such a way as to alter the desired path even if one begins to fully understand the consequences of one’s actions. Hence, over time a person with the most pernicious of addictions might rationally choose to continue in her potentially destructive behavior.

EXAMPLE 6.6 Experimental Evidence

Richard Hernstein and several colleagues conducted a set of trial experiments to see if people could discern the impact of one choice on future available choices. Participants played a simple computer game in which they were presented a screen with two “money machines.” In each of 400 periods, the machines would be labeled with the amount of money they would dispense if chosen for that period. The participants could choose either the left or right machine in each period. The payoffs were set up to mirror the cigarette problem discussed earlier in that the percentages of times one of the machines was chosen affected the payoff from that activity in the future, and the percentage of times the other was chosen had no effect. They then compared the subjects’ behavior to see if it was closer to the meliorating optimum or the true optimum payout. In fact, almost all subjects received payouts that fell somewhere in between, suggesting that behavior might not be quite so simple as the narrow-bracketing story.

|

|

|

|

|

148 |

|

BRACKETING DECISIONS |

EXAMPLE 6.7 The New York Taxi Problem

Cab drivers in New York City have the flexibility to decide how long they work in any given day. The cab driver rents the cab for a fixed fee per 12-hour shift (in the 1990s it was about $80), and can decide to return the cab early if she wishes. She faces a fine if the cab is returned late. The earnings for any particular time period can depend heavily on the particular day. For example, more people are likely to take a cab in the rain so they can avoid getting soaked from a long walk. Cultural events might also drive spikes in demand. Traditional economic theory suggests that when demand is high, and hourly wages are thus relatively high, the driver should choose to work longer hours. When wages are high over brief periods, one can make more money for the same effort. On the other hand, when wages are low for a brief period, the driver should work shorter hours, because the marginal benefit for labor is lower.

Colin Camerer and several colleagues examined the behavior of taxi drivers to determine if they responded according to economic theory when transitory shocks like weather affected their wages. They found that hourly wages are in fact negatively related to the hours worked in a particular day for an individual cab driver. Thus, the higher the marginal revenue of an hour of labor for the day, the less the driver decides to work. Moreover, the supply elasticity of labor among the less-experienced cab drivers is close to −1; thus for every 1 percent increase in revenue per hour, there is a 1 percent decrease in hours worked. This is consistent with the cab drivers targeting a particular amount of revenue each day and then quitting. If the driver is loss averse, she might set the rental rate for the cab (plus living expenses) as a reference point and feel a substantial loss below this level. In fact, some drivers who drive a company car without paying for the lease do not display the same bias. However, the target-income explanation only makes sense if the driver brackets labor supply choices by day. If considering over several days, one could take advantage of the effect of averaging wages over many days and decide to quit early when there is little business and decide to work later when there is lots of business. On average, cab drivers could have increased their income by 8 percent without increasing the number of hours worked in total by responding rationally to wage incentives. This might also explain why it is so difficult to find a cab on a rainy day.

EXAMPLE 6.8 For Only a Dollar a Day

Narrow bracketing can potentially lead to people ignoring the consequence of small transactions. For example, transactions for only a dollar or less might not seem like enough to care about on their own when failing to account for the sheer number of transactions one makes for such small amounts. This is called the peanuts effect. Often, financial advice columns suggest that people who are seeking to cut back on their spending look first at the smallest of transactions. For example, one might not consider a cup of coffee at a local coffee house to be a big expense and thus not consequential. Nonetheless, the amount of money spent each day on small items can add up quickly. Such an effect is often used to advertise lease agreements for cars, appliances, or