- •Table of Contents

- •Foreword

- •OECD Journal on Budgeting

- •Board of Advisors

- •Preface

- •Executive Summary

- •Sharp differences exist in the legal framework for budget systems

- •Public finance and legal theories do not explain inter-country differences in budget system laws

- •Political variables and legal culture help explain the inter-country differences

- •Norms for budget systems have been issued and many should be in budget system laws

- •Budget system laws are adopted to strengthen the powers of the legislature or the executive

- •Country studies reveal a multiplicity of reasons for adopting budget-related laws

- •Conclusions

- •1. Introduction

- •2. Budget processes

- •2.1. Budgeting: a five-stage process

- •Figure I.1. The roles of Parliament and the executive in the budget cycle

- •2.2. How are the different legal frameworks for budget systems organised?

- •Figure I.2. Different models for organising the legal framework of budget systems

- •3. Can economic theory explain the differences?

- •3.1. New institutional economics

- •3.2. Law, economics and public choice theory

- •3.3. Constitutional political economy: budgetary rules and budgetary outcomes

- •3.4. Can game theory help?

- •4. Can comparative law explain the differences?

- •4.1. Families of legal systems and the importance of the constitution

- •Box I.2. Purposes of constitutions and characteristics of statutes

- •4.2. Absence of norms for constitutions partly explains differences in budget system laws

- •4.3. Hierarchy within primary law also partly explains differences in budget-related laws

- •Box I.3. Hierarchy of laws: The example of Spain

- •4.4. Not all countries complete all steps of formal law-making processes

- •Box I.4. Steps in making law

- •4.5. Greater use is made of secondary law in some countries

- •Table I.1. Delegated legislation and separation of powers

- •4.6. Decisions and regulations of the legislature are particularly important in some countries

- •4.8. Are laws “green lights” or “red lights”?

- •5. Forms of government and budget system laws

- •5.1. Constitutional or parliamentary monarchies

- •5.2. Presidential and semi-presidential governments

- •5.3. Parliamentary republics

- •5.4. Relationship between forms of government and budget system law

- •Table I.2. Differences in selected budgetary powers of the executive and the legislature

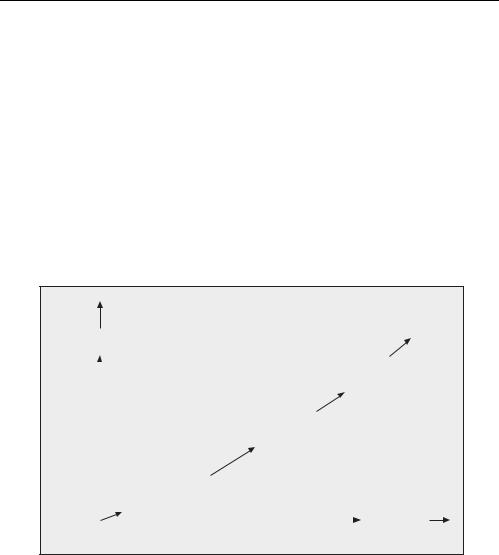

- •Figure I.3. Separation of powers and the need to adopt budget-related laws

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Introduction

- •Figure II.1. Density of legal framework for budget systems in 25 OECD countries

- •Table II.1. Legal frameworks for budget systems: 13 OECD countries

- •2. Different purposes of the legal frameworks for budget systems

- •Box II.1. Purposes of budget system laws

- •2.1. Legal necessity?

- •Figure II.2. Budget reforms and changes in budget laws

- •2.2. Budget reform: when is law required?

- •2.3. Elaborating on the budget powers of the legislature vis-à-vis the executive

- •3. Differences in the legal framework for the main actors in budget systems

- •3.1. Legislatures

- •3.2. Executives

- •Box II.2. New Zealand’s State Sector Act 1988

- •3.3. Judiciary

- •3.4. External audit offices

- •Table II.3. External audit legal frameworks: Selected differences

- •3.5. Sub-national governments

- •3.6. Supra-national bodies and international organisations

- •4. Differences in the legal framework for budget processes

- •4.1. Budget preparation by the executive

- •Table II.4. Legal requirements for the date of submission of the budget to the legislature

- •Box II.3. France: Legal requirements for budget information

- •4.2. Parliamentary approval of the budget

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting systems

- •Box II.4. Finland: Legal requirements for annual report and annual accounts

- •Table II.5. Legal requirements for submission of annual report to the legislature: Selected countries

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Have standards for the legal framework of budget systems been drawn up?

- •1.1. Normative and positive approaches to budget law

- •1.2. Limited guidance from normative constitutional economics

- •2. Who should set and monitor legally binding standards?

- •2.1. Role of politicians and bureaucrats

- •2.2. International transmission of budget system laws

- •2.3. International organisations as standard setters

- •Box III.1. The OECD Best Practices for Budget Transparency

- •Box III.2. Constitutional norms for external audit: Extracts from the INTOSAI “Lima Declaration”

- •2.4. Monitoring standards

- •3. Principles to support the legal framework of budget systems

- •Box III.3. Ten principles for a budget law

- •3.1. Authoritativeness

- •Table III.1. Stages of the budget cycle and legal instruments

- •3.2. Annual basis

- •3.3. Universality

- •3.4. Unity

- •3.5. Specificity

- •3.6. Balance

- •3.7. Accountability

- •Box III.4. Possible minimum legal norms for budget reporting

- •Box III.5. Ingredients of legal norms for external audit

- •3.8. Transparency

- •Box III.6. Ingredients of legal norms for government agencies

- •3.9. Stability or predictability

- •3.10. Performance (or efficiency, economy, and effectiveness)

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Canada: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •Box 2. Canada: Main provisions of the Spending Control Act 1992

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Roles and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. Canada: Major transfers from the federal to the provincial governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. Canada: Key steps in the annual budgeting process

- •Box 5. Canada: Major contents of the main estimates

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •Box 6. Canada: The budget approval process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. France: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. France: Key features of the Local Government Code

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Germany: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •Box 2. Germany: Public agencies

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •Box 3. Germany: Budget processes in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit17

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Japan: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •Box 2. Japan: Main contents of the 1997 Fiscal Structural Reform Act

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. Japan: Grants from central government to local governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. Japan: The timetable for the budget process

- •Box 5. Japan: Additional documents attached to the draft budget

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Korea: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. Korea: Major acts governing the fiscal relationship across government levels

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. Korea: Legal requirements for the timetable for budget preparation and deliberation

- •Box 5. Korea: Other documents annexed to the draft budget

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 2. New Zealand: Fiscal responsibility (legal provisions)

- •Box 3. New Zealand: Key steps and dates for budget preparation by the government

- •Box 4. New Zealand: Information required to support the first appropriation act

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Nordic Countries: The main budget system laws or near-laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The constitutions of the four countries

- •Table 1. Nordic countries: Age and size of constitutions

- •3.2. Legislatures

- •Table 2. Nordic countries: Constitutional provisions for the legislatures

- •3.3. The political executive

- •Table 3. Nordic countries: Constitutional provisions for the political executive

- •3.4. Ministries and executive agencies

- •3.5. Civil service

- •3.6. Sub-national governments

- •4. Constitutional and other legal requirements for budgeting

- •4.1. Authority of Parliament

- •Table 4. Nordic countries: Constitutional provisions for the authority of Parliament

- •4.2. Timing of submission of the annual budget

- •4.3. Non-adoption of the annual budget before the year begins

- •4.4. Content of the budget and types of appropriations

- •4.5. Documents to accompany the draft budget law

- •4.6. Parliamentary committees and budget procedures in Parliament

- •4.7. Parliamentary amendment powers, coalition agreements, two-stage budgeting and fiscal rules

- •4.8. Supplementary budgets

- •4.10. Cancellation of appropriations and contingency funds

- •4.11. Government accounting

- •4.12. Other fiscal reporting and special reports

- •Table 5. Nordic countries: Constitutional requirements for external audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Spain: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 2. Spain: The timetable for the budget process (based on the fiscal year 2003)

- •Box 3. Spain: The major content of medium-term budget plans

- •Box 4. Spain: Additional documents attached to the draft budget

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. United Kingdom: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system law

- •Box 2. United Kingdom: Reforms of the budget system in the past 20 years

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •Box 3. United Kingdom: Executive agencies and other bodies

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •Box 4. United Kingdom: Budget processes in Parliament

- •Table 1. United Kingdom: Format of appropriation adopted by Parliament for Department X

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •Table 2. United Kingdom: Transfers of budgetary authority

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Box 5. United Kingdom: External audit arrangements

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. United States: Main federal budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. United States: Major transfers between different levels of government

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. United States: Key steps in the annual budget process within the executive

- •Box 5. United States: Other information required by law

- •4.2. Budget process in the legislature

- •Box 6. United States: Legal and internal deadlines for congressional budget approval

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •5. Sanctions and non-compliance

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

I.COMPARATIVE LAW, CONSTITUTIONS, POLITICS AND BUDGET SYSTEMS

5.2. Presidential and semi-presidential governments

The key characteristic of a presidential system is that the head of State is directly elected by the people, in clear contrast to monarchies. Under a “pure” presidential system, the directly elected head of State, by constitutional design, is also the head of the executive. All executive power is vested in one person, not a collective body such as a Cabinet of ministers. However, the president’s room to manoeuvre in budget matters is constrained by the extent that the legislature dictates the “rules of game” of budget management by adopting laws or imposing other rules.

A “pure” presidential system operates in the United States and other countries on the American continent. The United States president’s powers are “balanced” by those of a House of Representatives, a Senate, and a judiciary. This form of government is characterised by very strong separation of powers.

In a semi-presidential system, the head of State – the president – is also directly elected. However, the executive is divided between the head of State and the head of government, the prime minister (who is usually the leader of the majority political ruling parties at the time of legislative elections). The president may have strong powers, specified in a written constitution. Finland, France,17 and Korea have adopted a model in which the prime minister is formally appointed by the president after approval or election by Parliament. In contrast to the Westminster system, any elected parliamentarians usually must resign from Parliament to become a Cabinet minister – the two functions are perceived to be incompatible.

5.3. Parliamentary republics

In several respects, parliamentary republics are similar to semi-presidential systems. The major difference is that the president is not directly elected by citizens. The presidents of such countries generally have weaker constitutional powers. Germany and Italy are examples. In these countries, the head of the Cabinet of ministers (e.g. the Chancellor in Germany) plays the politically dominate role and speaks for the parliamentary majority. Cabinets are formed mainly from parliamentarians (who must resign from Parliament), although non-elected officials may be appointed.

5.4. Relationship between forms of government and budget system law

The relative strength of executives and legislatures varies considerably according to the form of government. Under a pure presidential system, the separation of the legislature from the executive is specified in the constitution. By adopting laws, the legislature can reinforce its supremacy over the executive in budgetary matters.

48 |

OECD JOURNAL ON BUDGETING – VOLUME 4 – NO. 3 – ISSN 1608-7143 – © OECD 2004 |

|

I.COMPARATIVE LAW, CONSTITUTIONS, POLITICS AND BUDGET SYSTEMS

In parliamentary systems there is less separation of the executive and the legislature. Provided discipline within the ruling party or parties is maintained, the government can propose laws to Parliament, which adopts them with relative ease. Maintaining party discipline is easier in two-party systems than in multiparty systems, where reaching and maintaining a consensus within the coalition parties that make up the government can be troublesome. In both systems, however, the main effective tool that Parliaments have for “controlling” the executive is to propose a vote of no-confidence in the government and cause its collapse if the vote succeeds. This happens rarely in parliamentary monarchies that have first-past-the-post electoral systems. In such countries, in budgetary matters, the executive holds the “power of the purse”, even though, constitutionally, Parliament is said to be supreme in money matters.

A detailed comparison of specific budget powers embodied in primary law is provided in Part III. On the basis of budget-related laws, the legislatures in the countries with a strong separation of the legislative and executive branches have strong powers in relation to budget processes, including powers to:

●Specify the timing of submission of the draft budget to the legislature.

●Decide, for the annual budget and the medium-term budget framework, the levels of the aggregates for revenues, spending, and new borrowing.

●Ensure that plenty of time is allowed for budgetary debate in the legislature.

●Specify the nature, form and duration of the appropriations for annual budgets, as well as the supplementary information required to accompany the draft annual budget law.

●Amend the executive’s draft budget, possibly without any legal constraints, for both total expenditure and the composition of spending programmes.

●Prevent the executive from withholding spending, once the annual budget is approved (i.e. provide the executive with weak or no powers to cancel or defer spending approved by the legislature).

●Decide on the number, size, and uses of extra-budgetary funds, by adopting specific laws.

●Limit to the maximum the executive’s ability to manipulate government funds outside the purview of the legislature.

●Require substantial ex post budgetary information, including an audit of the financial accounts and an annual performance review of budget execution relative to the approved budget.

●Define the main roles of a supreme audit institution and require that it serves primarily the needs of the legislature.

OECD JOURNAL ON BUDGETING – VOLUME 4 – NO. 3 – ISSN 1608-7143 – © OECD 2004 |

49 |

|

I.COMPARATIVE LAW, CONSTITUTIONS, POLITICS AND BUDGET SYSTEMS

●Require officials from the executive to defend budgetary outcomes before committees of the legislature and to report on identified cases of financial mismanagement.

A number of the above differences – between a country with an executivedominated Parliament (the United Kingdom) and a country with a very strong separation of executive and legislative powers (the United States) – are illustrated in Table I.2.

Table I.2. Differences in selected budgetary powers of the executive and the legislature

United Kingdom |

United States |

|

|

Executive

An executive office drafts |

H.M. Treasury prepares a draft |

the annual budget. |

budget for Cabinet approval, |

|

subject to government-decided |

|

rules on fiscal aggregates, which |

|

will not be challenged by |

|

Parliament. |

The Office of Management and Budget, a presidential agency, prepares a draft detailed budget. The executive may propose

a medium-term fiscal strategy, but this is not binding on Congress, which has unlimited power to adopt its own fiscal strategy.

The political executive proposes |

The Chancellor of the Exchequer |

the budget to Parliament. |

makes a speech, at around |

|

the beginning of the fiscal year, |

|

outlining the decisions that |

|

Cabinet has reached on all |

|

important budget matters. |

Legislature |

|

|

|

The legislature considers |

Yes, but only in the House of |

the budget in committees. |

Commons. Most committees take |

|

little interest in the draft budget, |

|

mainly because any proposals |

|

for substantial changes are |

|

unlikely to be adopted. Such |

|

proposals are vetted by the House |

|

of Commons Liaison Committee |

|

and only three days of debate are |

|

allowed in plenary session. |

The legislature approves |

Yes, but the adoption of finance |

the budget as law. |

acts and appropriation acts are |

|

mere formalities – they are not |

|

debated at the stage when the |

|

budget becomes formal law. |

The President submits a draft budget to Congress eight months before the new fiscal year begins.

The President’s budget provides

a baseline for the “real” budget that is made by the legislature.

Budget committees of both the House of Representatives and the Senate first agree on a “budget resolution” which could propose fiscal aggregates quite different from those proposed by the President. Subsequently, appropriation sub-committees may alter budget programmes substantially.

Yes, for discretionary spending, the budget becomes law in the form of 13 separate appropriation bills, which cover about one-third of total federal expenditure. Non-

discretionary spending and taxes are also approved but by other laws.

50 |

OECD JOURNAL ON BUDGETING – VOLUME 4 – NO. 3 – ISSN 1608-7143 – © OECD 2004 |

|

I.COMPARATIVE LAW, CONSTITUTIONS, POLITICS AND BUDGET SYSTEMS

It appears that when the legislative and executive branches are strongly separated, there is a greater tendency for legislatures to specify the content, detail and powers contained over the budget system in primary law (Figure I.3). In countries with political systems with a strong separation of powers, the legislature is reluctant to delegate law-making authority (Epstein and O’Halloran, 1999). Their strong powers are upheld by the courts. In contrast, delegation of law making by Parliaments, or maintenance of existing law-making powers by executives, is strong in countries with a weak separation of the executive from Parliament. In such countries, the representation of the government on parliamentary committees allows the executive to maintain those powers. A strong committee system has been found to derive from the larger constitutional context, with committees established in part to oversee executive agencies and thereby limit the powers of the executive (Epstein and O’Halloran, 2001).

Figure I.3. Separation of powers and the need to adopt budget-related laws

Presidential

Increasing

|

Semi-presidential systems |

|

|

||

|

and parliamentary republics |

|

Need to |

Parliamentary monarchies with |

|

adopt |

coalition governments |

|

law for |

|

|

budget |

|

|

system |

|

|

|

Parliamentary monarchies with |

|

|

first-past-the-post electoral system |

|

|

|

Increasing |

|

|

|

|

Strength of separation of executive and legislature |

|

Although the strength of the legislature’s powers in budget management is particularly strong in countries with strong legislatures relative to executives, the relationship is not necessarily one to one (as drawn in Figure I.2 for illustrative purposes). Other factors influencing the need for a country to regulate the budget system by the adoption of law include:

●The political system, particularly: 1) whether there is a bicameral or a unicameral system. the existence of a bicameral system in a Parliament, in which the second chamber also has strong powers in relation to budgeting, swings the balance of budgeting powers towards the legislature relative to a

OECD JOURNAL ON BUDGETING – VOLUME 4 – NO. 3 – ISSN 1608-7143 – © OECD 2004 |

51 |

|