- •Table of Contents

- •Foreword

- •OECD Journal on Budgeting

- •Board of Advisors

- •Preface

- •Executive Summary

- •Sharp differences exist in the legal framework for budget systems

- •Public finance and legal theories do not explain inter-country differences in budget system laws

- •Political variables and legal culture help explain the inter-country differences

- •Norms for budget systems have been issued and many should be in budget system laws

- •Budget system laws are adopted to strengthen the powers of the legislature or the executive

- •Country studies reveal a multiplicity of reasons for adopting budget-related laws

- •Conclusions

- •1. Introduction

- •2. Budget processes

- •2.1. Budgeting: a five-stage process

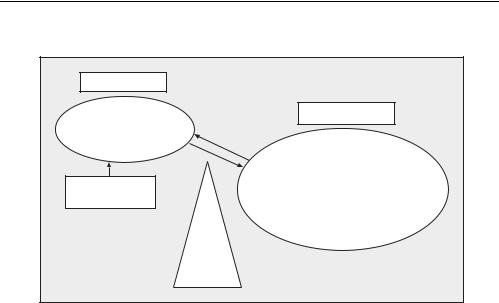

- •Figure I.1. The roles of Parliament and the executive in the budget cycle

- •2.2. How are the different legal frameworks for budget systems organised?

- •Figure I.2. Different models for organising the legal framework of budget systems

- •3. Can economic theory explain the differences?

- •3.1. New institutional economics

- •3.2. Law, economics and public choice theory

- •3.3. Constitutional political economy: budgetary rules and budgetary outcomes

- •3.4. Can game theory help?

- •4. Can comparative law explain the differences?

- •4.1. Families of legal systems and the importance of the constitution

- •Box I.2. Purposes of constitutions and characteristics of statutes

- •4.2. Absence of norms for constitutions partly explains differences in budget system laws

- •4.3. Hierarchy within primary law also partly explains differences in budget-related laws

- •Box I.3. Hierarchy of laws: The example of Spain

- •4.4. Not all countries complete all steps of formal law-making processes

- •Box I.4. Steps in making law

- •4.5. Greater use is made of secondary law in some countries

- •Table I.1. Delegated legislation and separation of powers

- •4.6. Decisions and regulations of the legislature are particularly important in some countries

- •4.8. Are laws “green lights” or “red lights”?

- •5. Forms of government and budget system laws

- •5.1. Constitutional or parliamentary monarchies

- •5.2. Presidential and semi-presidential governments

- •5.3. Parliamentary republics

- •5.4. Relationship between forms of government and budget system law

- •Table I.2. Differences in selected budgetary powers of the executive and the legislature

- •Figure I.3. Separation of powers and the need to adopt budget-related laws

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Introduction

- •Figure II.1. Density of legal framework for budget systems in 25 OECD countries

- •Table II.1. Legal frameworks for budget systems: 13 OECD countries

- •2. Different purposes of the legal frameworks for budget systems

- •Box II.1. Purposes of budget system laws

- •2.1. Legal necessity?

- •Figure II.2. Budget reforms and changes in budget laws

- •2.2. Budget reform: when is law required?

- •2.3. Elaborating on the budget powers of the legislature vis-à-vis the executive

- •3. Differences in the legal framework for the main actors in budget systems

- •3.1. Legislatures

- •3.2. Executives

- •Box II.2. New Zealand’s State Sector Act 1988

- •3.3. Judiciary

- •3.4. External audit offices

- •Table II.3. External audit legal frameworks: Selected differences

- •3.5. Sub-national governments

- •3.6. Supra-national bodies and international organisations

- •4. Differences in the legal framework for budget processes

- •4.1. Budget preparation by the executive

- •Table II.4. Legal requirements for the date of submission of the budget to the legislature

- •Box II.3. France: Legal requirements for budget information

- •4.2. Parliamentary approval of the budget

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting systems

- •Box II.4. Finland: Legal requirements for annual report and annual accounts

- •Table II.5. Legal requirements for submission of annual report to the legislature: Selected countries

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Have standards for the legal framework of budget systems been drawn up?

- •1.1. Normative and positive approaches to budget law

- •1.2. Limited guidance from normative constitutional economics

- •2. Who should set and monitor legally binding standards?

- •2.1. Role of politicians and bureaucrats

- •2.2. International transmission of budget system laws

- •2.3. International organisations as standard setters

- •Box III.1. The OECD Best Practices for Budget Transparency

- •Box III.2. Constitutional norms for external audit: Extracts from the INTOSAI “Lima Declaration”

- •2.4. Monitoring standards

- •3. Principles to support the legal framework of budget systems

- •Box III.3. Ten principles for a budget law

- •3.1. Authoritativeness

- •Table III.1. Stages of the budget cycle and legal instruments

- •3.2. Annual basis

- •3.3. Universality

- •3.4. Unity

- •3.5. Specificity

- •3.6. Balance

- •3.7. Accountability

- •Box III.4. Possible minimum legal norms for budget reporting

- •Box III.5. Ingredients of legal norms for external audit

- •3.8. Transparency

- •Box III.6. Ingredients of legal norms for government agencies

- •3.9. Stability or predictability

- •3.10. Performance (or efficiency, economy, and effectiveness)

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Canada: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •Box 2. Canada: Main provisions of the Spending Control Act 1992

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Roles and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. Canada: Major transfers from the federal to the provincial governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. Canada: Key steps in the annual budgeting process

- •Box 5. Canada: Major contents of the main estimates

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •Box 6. Canada: The budget approval process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. France: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. France: Key features of the Local Government Code

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Germany: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •Box 2. Germany: Public agencies

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •Box 3. Germany: Budget processes in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit17

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Japan: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •Box 2. Japan: Main contents of the 1997 Fiscal Structural Reform Act

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. Japan: Grants from central government to local governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. Japan: The timetable for the budget process

- •Box 5. Japan: Additional documents attached to the draft budget

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Korea: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. Korea: Major acts governing the fiscal relationship across government levels

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. Korea: Legal requirements for the timetable for budget preparation and deliberation

- •Box 5. Korea: Other documents annexed to the draft budget

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 2. New Zealand: Fiscal responsibility (legal provisions)

- •Box 3. New Zealand: Key steps and dates for budget preparation by the government

- •Box 4. New Zealand: Information required to support the first appropriation act

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Nordic Countries: The main budget system laws or near-laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The constitutions of the four countries

- •Table 1. Nordic countries: Age and size of constitutions

- •3.2. Legislatures

- •Table 2. Nordic countries: Constitutional provisions for the legislatures

- •3.3. The political executive

- •Table 3. Nordic countries: Constitutional provisions for the political executive

- •3.4. Ministries and executive agencies

- •3.5. Civil service

- •3.6. Sub-national governments

- •4. Constitutional and other legal requirements for budgeting

- •4.1. Authority of Parliament

- •Table 4. Nordic countries: Constitutional provisions for the authority of Parliament

- •4.2. Timing of submission of the annual budget

- •4.3. Non-adoption of the annual budget before the year begins

- •4.4. Content of the budget and types of appropriations

- •4.5. Documents to accompany the draft budget law

- •4.6. Parliamentary committees and budget procedures in Parliament

- •4.7. Parliamentary amendment powers, coalition agreements, two-stage budgeting and fiscal rules

- •4.8. Supplementary budgets

- •4.10. Cancellation of appropriations and contingency funds

- •4.11. Government accounting

- •4.12. Other fiscal reporting and special reports

- •Table 5. Nordic countries: Constitutional requirements for external audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. Spain: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 2. Spain: The timetable for the budget process (based on the fiscal year 2003)

- •Box 3. Spain: The major content of medium-term budget plans

- •Box 4. Spain: Additional documents attached to the draft budget

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. United Kingdom: Main budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system law

- •Box 2. United Kingdom: Reforms of the budget system in the past 20 years

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •Box 3. United Kingdom: Executive agencies and other bodies

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •4.2. Budget process in Parliament

- •Box 4. United Kingdom: Budget processes in Parliament

- •Table 1. United Kingdom: Format of appropriation adopted by Parliament for Department X

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •Table 2. United Kingdom: Transfers of budgetary authority

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •Box 5. United Kingdom: External audit arrangements

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

- •1. Overview

- •1.1. The legal framework governing budget processes

- •Box 1. United States: Main federal budget system laws

- •1.2. Reforms of budget system laws

- •2. Principles underlying budget system laws

- •3. Legal basis for the establishment and the powers of the actors in the budget system

- •3.1. The executive and the legislature

- •3.2. Role and responsibilities of sub-national governments

- •Box 3. United States: Major transfers between different levels of government

- •4. Legal provisions for each stage of the budget cycle

- •4.1. Budget preparation and presentation by the executive

- •Box 4. United States: Key steps in the annual budget process within the executive

- •Box 5. United States: Other information required by law

- •4.2. Budget process in the legislature

- •Box 6. United States: Legal and internal deadlines for congressional budget approval

- •4.3. Budget execution

- •4.4. Government accounting and fiscal reporting

- •4.5. External audit

- •5. Sanctions and non-compliance

- •Notes

- •Bibliography

I.COMPARATIVE LAW, CONSTITUTIONS, POLITICS AND BUDGET SYSTEMS

Most of this book is confined to discussing the differences across countries in the budgetary provisions of constitutions and statutes. However, other legal instruments can, and do, govern budgetary processes and different countries assign different weights to the importance of constitutions, statute laws, regulations of various types, and extra-legal instruments. This part examines pertinent issues. Theory does not allow strong conclusions to be drawn. Although self-imposed budget-related norms are one way of limiting capriciousness in budget processes, the choice and combination of the legal and quasi-legal instruments intended to limit the powers and roles of specific actors in the budget processes appear arbitrary.

Budget rules, if embodied in law, are useful only if the rules are both enforceable and enforced in practice. For budget-related law, many provisions are “green lights” – they specify desirable features to be implemented by budget players. A few provisions of budget-related laws are “red lights” – rules that governments must not break. Courts are called on to make judgements for any “red light” infractions. Legal arrangements and laws for the enforcement of such rules differ widely across countries.2

Unless mandated constitutionally, the judiciary appears reluctant to enter into struggles that are inherently political in nature. Budget-related laws appear to be better confined to formalising agreements that would otherwise be respected on a voluntary basis – “self-enforcing” laws. The experience with coalition agreements in some countries suggests that voluntary pacts, if adhered to, are as effective as legally binding arrangements. Such voluntary agreements are even superior – in terms of achieving desirable fiscal objectives – to formal laws that are not respected.

Part II compares the extent to which law is used to specify budget players and processes, with a particular focus on 13 OECD member countries. Part III elaborates on which aspects of the budget system could usefully be incorporated in law, as opposed to voluntary restraints that are not legally binding. The remainder of Part I briefly examines what is meant by “budget processes”. Most of the subsequent discussion then addresses the question: “Why is the legal framework for budget systems organised so differently in OECD countries?”

2. Budget processes

2.1. Budgeting: a five-stage process

Five generic stages of annual budget processes can be identified (see Figure I.1). First the executive prepares a draft budget and submits it to the legislature. This is usually a two-step process: a Ministry of Finance (or equivalent) prepares a draft budget that incorporates the government’s expressed budget orientation; the draft budget prepared by bureaucrats is then approved by a Cabinet of ministers (or the equivalent for countries with

OECD JOURNAL ON BUDGETING – VOLUME 4 – NO. 3 – ISSN 1608-7143 – © OECD 2004 |

25 |

|

I.COMPARATIVE LAW, CONSTITUTIONS, POLITICS AND BUDGET SYSTEMS

Figure I.1. The roles of Parliament and the executive in the budget cycle

Parliament

2. Approves annual budget.

4.Controls implementation of the budget.

External audit

5.Independent audit.

The executive

1.Prepares budget (macro framework, fiscal policy strategy and priorities, detailed budget projections).

3.Executes budget (collects revenues, controls expenditures) and prepares reports for own use and for Parliament.

presidential political systems). This budget is submitted to the legislature for possible amendment and approval.

Second, at the Parliamentary stage, the budget is generally discussed in parliamentary committees, which may propose amendments. Once amendments are agreed in plenary session, the legislature approves the budget. Legal authority is provided to the executive for raising revenues if this is not ongoing. Formal adoption of the spending proposals means that legally binding upper limits are established for many expenditure categories.

The third stage is the implementation of the approved budget which is performed by the executive – and/or government agencies. In so doing, a central budget office (usually in the Ministry of Finance or the equivalent) monitors budget implementation and prepares periodic budget execution reports using a well-defined accounting system. The executive may be provided with the power to change the approved budget in the case of unforeseen emergencies, including major deviations in the macroeconomic framework underlying the budget law. A supplementary budget may be needed to confirm any such action by the executive. The executive may also be provided with other powers to modify the approved budget, including powers to change its composition (e.g. by virement or by using a reserve fund approved in the annual budget) or to control actual spending to a level below that approved, should economic circumstances dictate.

The fourth stage is parliamentary control of budget implementation. This takes place both during and, especially, after the close of the fiscal year.

26 |

OECD JOURNAL ON BUDGETING – VOLUME 4 – NO. 3 – ISSN 1608-7143 – © OECD 2004 |

|