- •About the author

- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •This Book’s Approach

- •What’s New in the Seventh Edition?

- •The Arrangement of Topics

- •Part One, Introduction

- •Part Two, Classical Theory: The Economy in the Long Run

- •Part Three, Growth Theory: The Economy in the Very Long Run

- •Part Four, Business Cycle Theory: The Economy in the Short Run

- •Part Five, Macroeconomic Policy Debates

- •Part Six, More on the Microeconomics Behind Macroeconomics

- •Epilogue

- •Alternative Routes Through the Text

- •Learning Tools

- •Case Studies

- •FYI Boxes

- •Graphs

- •Mathematical Notes

- •Chapter Summaries

- •Key Concepts

- •Questions for Review

- •Problems and Applications

- •Chapter Appendices

- •Glossary

- •Translations

- •Acknowledgments

- •Supplements and Media

- •For Instructors

- •Instructor’s Resources

- •Solutions Manual

- •Test Bank

- •PowerPoint Slides

- •For Students

- •Student Guide and Workbook

- •Online Offerings

- •EconPortal, Available Spring 2010

- •eBook

- •WebCT

- •BlackBoard

- •Additional Offerings

- •i-clicker

- •The Wall Street Journal Edition

- •Financial Times Edition

- •Dismal Scientist

- •1-1: What Macroeconomists Study

- •1-2: How Economists Think

- •Theory as Model Building

- •The Use of Multiple Models

- •Prices: Flexible Versus Sticky

- •Microeconomic Thinking and Macroeconomic Models

- •1-3: How This Book Proceeds

- •Income, Expenditure, and the Circular Flow

- •Rules for Computing GDP

- •Real GDP Versus Nominal GDP

- •The GDP Deflator

- •Chain-Weighted Measures of Real GDP

- •The Components of Expenditure

- •Other Measures of Income

- •Seasonal Adjustment

- •The Price of a Basket of Goods

- •The CPI Versus the GDP Deflator

- •The Household Survey

- •The Establishment Survey

- •The Factors of Production

- •The Production Function

- •The Supply of Goods and Services

- •3-2: How Is National Income Distributed to the Factors of Production?

- •Factor Prices

- •The Decisions Facing the Competitive Firm

- •The Firm’s Demand for Factors

- •The Division of National Income

- •The Cobb–Douglas Production Function

- •Consumption

- •Investment

- •Government Purchases

- •Changes in Saving: The Effects of Fiscal Policy

- •Changes in Investment Demand

- •3-5: Conclusion

- •4-1: What Is Money?

- •The Functions of Money

- •The Types of Money

- •The Development of Fiat Money

- •How the Quantity of Money Is Controlled

- •How the Quantity of Money Is Measured

- •4-2: The Quantity Theory of Money

- •Transactions and the Quantity Equation

- •From Transactions to Income

- •The Assumption of Constant Velocity

- •Money, Prices, and Inflation

- •4-4: Inflation and Interest Rates

- •Two Interest Rates: Real and Nominal

- •The Fisher Effect

- •Two Real Interest Rates: Ex Ante and Ex Post

- •The Cost of Holding Money

- •Future Money and Current Prices

- •4-6: The Social Costs of Inflation

- •The Layman’s View and the Classical Response

- •The Costs of Expected Inflation

- •The Costs of Unexpected Inflation

- •One Benefit of Inflation

- •4-7: Hyperinflation

- •The Costs of Hyperinflation

- •The Causes of Hyperinflation

- •4-8: Conclusion: The Classical Dichotomy

- •The Role of Net Exports

- •International Capital Flows and the Trade Balance

- •International Flows of Goods and Capital: An Example

- •Capital Mobility and the World Interest Rate

- •Why Assume a Small Open Economy?

- •The Model

- •How Policies Influence the Trade Balance

- •Evaluating Economic Policy

- •Nominal and Real Exchange Rates

- •The Real Exchange Rate and the Trade Balance

- •The Determinants of the Real Exchange Rate

- •How Policies Influence the Real Exchange Rate

- •The Effects of Trade Policies

- •The Special Case of Purchasing-Power Parity

- •Net Capital Outflow

- •The Model

- •Policies in the Large Open Economy

- •Conclusion

- •Causes of Frictional Unemployment

- •Public Policy and Frictional Unemployment

- •Minimum-Wage Laws

- •Unions and Collective Bargaining

- •Efficiency Wages

- •The Duration of Unemployment

- •Trends in Unemployment

- •Transitions Into and Out of the Labor Force

- •6-5: Labor-Market Experience: Europe

- •The Rise in European Unemployment

- •Unemployment Variation Within Europe

- •The Rise of European Leisure

- •6-6: Conclusion

- •7-1: The Accumulation of Capital

- •The Supply and Demand for Goods

- •Growth in the Capital Stock and the Steady State

- •Approaching the Steady State: A Numerical Example

- •How Saving Affects Growth

- •7-2: The Golden Rule Level of Capital

- •Comparing Steady States

- •The Transition to the Golden Rule Steady State

- •7-3: Population Growth

- •The Steady State With Population Growth

- •The Effects of Population Growth

- •Alternative Perspectives on Population Growth

- •7-4: Conclusion

- •The Efficiency of Labor

- •The Steady State With Technological Progress

- •The Effects of Technological Progress

- •Balanced Growth

- •Convergence

- •Factor Accumulation Versus Production Efficiency

- •8-3: Policies to Promote Growth

- •Evaluating the Rate of Saving

- •Changing the Rate of Saving

- •Allocating the Economy’s Investment

- •Establishing the Right Institutions

- •Encouraging Technological Progress

- •The Basic Model

- •A Two-Sector Model

- •The Microeconomics of Research and Development

- •The Process of Creative Destruction

- •8-5: Conclusion

- •Increases in the Factors of Production

- •Technological Progress

- •The Sources of Growth in the United States

- •The Solow Residual in the Short Run

- •9-1: The Facts About the Business Cycle

- •GDP and Its Components

- •Unemployment and Okun’s Law

- •Leading Economic Indicators

- •9-2: Time Horizons in Macroeconomics

- •How the Short Run and Long Run Differ

- •9-3: Aggregate Demand

- •The Quantity Equation as Aggregate Demand

- •Why the Aggregate Demand Curve Slopes Downward

- •Shifts in the Aggregate Demand Curve

- •9-4: Aggregate Supply

- •The Long Run: The Vertical Aggregate Supply Curve

- •From the Short Run to the Long Run

- •9-5: Stabilization Policy

- •Shocks to Aggregate Demand

- •Shocks to Aggregate Supply

- •10-1: The Goods Market and the IS Curve

- •The Keynesian Cross

- •The Interest Rate, Investment, and the IS Curve

- •How Fiscal Policy Shifts the IS Curve

- •10-2: The Money Market and the LM Curve

- •The Theory of Liquidity Preference

- •Income, Money Demand, and the LM Curve

- •How Monetary Policy Shifts the LM Curve

- •Shocks in the IS–LM Model

- •From the IS–LM Model to the Aggregate Demand Curve

- •The IS–LM Model in the Short Run and Long Run

- •11-3: The Great Depression

- •The Spending Hypothesis: Shocks to the IS Curve

- •The Money Hypothesis: A Shock to the LM Curve

- •Could the Depression Happen Again?

- •11-4: Conclusion

- •12-1: The Mundell–Fleming Model

- •The Goods Market and the IS* Curve

- •The Money Market and the LM* Curve

- •Putting the Pieces Together

- •Fiscal Policy

- •Monetary Policy

- •Trade Policy

- •How a Fixed-Exchange-Rate System Works

- •Fiscal Policy

- •Monetary Policy

- •Trade Policy

- •Policy in the Mundell–Fleming Model: A Summary

- •12-4: Interest Rate Differentials

- •Country Risk and Exchange-Rate Expectations

- •Differentials in the Mundell–Fleming Model

- •Pros and Cons of Different Exchange-Rate Systems

- •The Impossible Trinity

- •12-6: From the Short Run to the Long Run: The Mundell–Fleming Model With a Changing Price Level

- •12-7: A Concluding Reminder

- •Fiscal Policy

- •Monetary Policy

- •A Rule of Thumb

- •The Sticky-Price Model

- •Implications

- •Adaptive Expectations and Inflation Inertia

- •Two Causes of Rising and Falling Inflation

- •Disinflation and the Sacrifice Ratio

- •13-3: Conclusion

- •14-1: Elements of the Model

- •Output: The Demand for Goods and Services

- •The Real Interest Rate: The Fisher Equation

- •Inflation: The Phillips Curve

- •Expected Inflation: Adaptive Expectations

- •The Nominal Interest Rate: The Monetary-Policy Rule

- •14-2: Solving the Model

- •The Long-Run Equilibrium

- •The Dynamic Aggregate Supply Curve

- •The Dynamic Aggregate Demand Curve

- •The Short-Run Equilibrium

- •14-3: Using the Model

- •Long-Run Growth

- •A Shock to Aggregate Supply

- •A Shock to Aggregate Demand

- •A Shift in Monetary Policy

- •The Taylor Principle

- •14-5: Conclusion: Toward DSGE Models

- •15-1: Should Policy Be Active or Passive?

- •Lags in the Implementation and Effects of Policies

- •The Difficult Job of Economic Forecasting

- •Ignorance, Expectations, and the Lucas Critique

- •The Historical Record

- •Distrust of Policymakers and the Political Process

- •The Time Inconsistency of Discretionary Policy

- •Rules for Monetary Policy

- •16-1: The Size of the Government Debt

- •16-2: Problems in Measurement

- •Measurement Problem 1: Inflation

- •Measurement Problem 2: Capital Assets

- •Measurement Problem 3: Uncounted Liabilities

- •Measurement Problem 4: The Business Cycle

- •Summing Up

- •The Basic Logic of Ricardian Equivalence

- •Consumers and Future Taxes

- •Making a Choice

- •16-5: Other Perspectives on Government Debt

- •Balanced Budgets Versus Optimal Fiscal Policy

- •Fiscal Effects on Monetary Policy

- •Debt and the Political Process

- •International Dimensions

- •16-6: Conclusion

- •Keynes’s Conjectures

- •The Early Empirical Successes

- •The Intertemporal Budget Constraint

- •Consumer Preferences

- •Optimization

- •How Changes in Income Affect Consumption

- •Constraints on Borrowing

- •The Hypothesis

- •Implications

- •The Hypothesis

- •Implications

- •The Hypothesis

- •Implications

- •17-7: Conclusion

- •18-1: Business Fixed Investment

- •The Rental Price of Capital

- •The Cost of Capital

- •The Determinants of Investment

- •Taxes and Investment

- •The Stock Market and Tobin’s q

- •Financing Constraints

- •Banking Crises and Credit Crunches

- •18-2: Residential Investment

- •The Stock Equilibrium and the Flow Supply

- •Changes in Housing Demand

- •18-3: Inventory Investment

- •Reasons for Holding Inventories

- •18-4: Conclusion

- •19-1: Money Supply

- •100-Percent-Reserve Banking

- •Fractional-Reserve Banking

- •A Model of the Money Supply

- •The Three Instruments of Monetary Policy

- •Bank Capital, Leverage, and Capital Requirements

- •19-2: Money Demand

- •Portfolio Theories of Money Demand

- •Transactions Theories of Money Demand

- •The Baumol–Tobin Model of Cash Management

- •19-3 Conclusion

- •Lesson 2: In the short run, aggregate demand influences the amount of goods and services that a country produces.

- •Question 1: How should policymakers try to promote growth in the economy’s natural level of output?

- •Question 2: Should policymakers try to stabilize the economy?

- •Question 3: How costly is inflation, and how costly is reducing inflation?

- •Question 4: How big a problem are government budget deficits?

- •Conclusion

- •Glossary

- •Index

C H A P T E R 1 2 The Open Economy Revisited: The Mundell-Fleming Model and the Exchange-Rate Regime | 375

Fiscal Policy

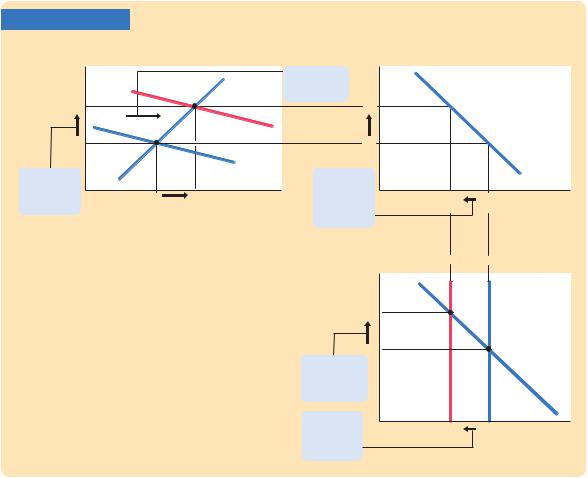

Figure 12-16 examines the impact of a fiscal expansion. An increase in government purchases or a cut in taxes shifts the IS curve to the right. As panel (a) illustrates, this shift in the IS curve leads to an increase in the level of income and an increase in the interest rate. These two effects are similar to those in a closed economy.

Yet, in the large open economy, the higher interest rate reduces the net capital outflow, as in panel (b). The fall in the net capital outflow reduces the supply of dollars in the market for foreign exchange. The exchange rate appreciates, as in panel (c). Because domestic goods become more expensive relative to foreign goods, net exports fall.

Figure 12-16 shows that a fiscal expansion does raise income in the large open economy, unlike in a small open economy under a floating exchange rate. The impact on income, however, is smaller than in a closed economy. In a closed economy, the expansionary impact of fiscal policy is partially offset by the crowding out of investment: as the interest rate rises, investment falls, reducing

FIGURE 12-16

(a) The IS–LM Model |

(b) Net Capital Outflow |

Real interest |

|

|

LM |

r |

|

|

|

rate, r |

|

|

1. A fiscal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

expansion ... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r2 |

|

|

IS2 |

r2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r1 |

|

|

|

r1 |

|

|

|

2. ... raises |

|

|

IS1 |

3. ... which |

|

|

CF(r) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

the interest |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Income, |

lowers net |

CF2 |

CF1 |

Net capital |

rate, ... |

capital |

||||||

|

|

|

output, Y |

outflow, ... |

|

|

outflow, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CF |

A Fiscal Expansion in a Large Open Economy Panel (a) shows that a fiscal expansion shifts the IS curve to the right. Income rises from Y1 to Y2, and the interest rate rises from r1 to r2. Panel (b) shows that the increase in the interest rate causes the net capital outflow to fall from CF1 to CF2. Panel (c) shows that the fall in the net capital outflow reduces the net supply of dollars, causing the exchange rate to rise from e1 to e2.

(c) The Market for Foreign Exchange

Exchange |

CF2 |

CF1 |

||

rate, e |

||||

e2 |

|

|

|

|

e1 |

|

|

|

|

4. ... raises |

|

|

|

|

the exchange |

|

|

|

|

rate, ... |

|

|

|

|

5. ... and |

|

|

NX(e) |

|

NX2 |

NX1 |

Net exports, |

||

reduces net |

||||

exports. |

|

|

NX |

|

|

|

|

||

376 | P A R T I V Business Cycle Theory: The Economy in the Short Run

the fiscal-policy multipliers. In a large open economy, there is yet another offsetting factor: as the interest rate rises, the net capital outflow falls, the currency appreciates in the foreign-exchange market, and net exports fall. Together these effects are not large enough to make fiscal policy powerless, as it is in a small open economy, but they do reduce the impact of fiscal policy.

Monetary Policy

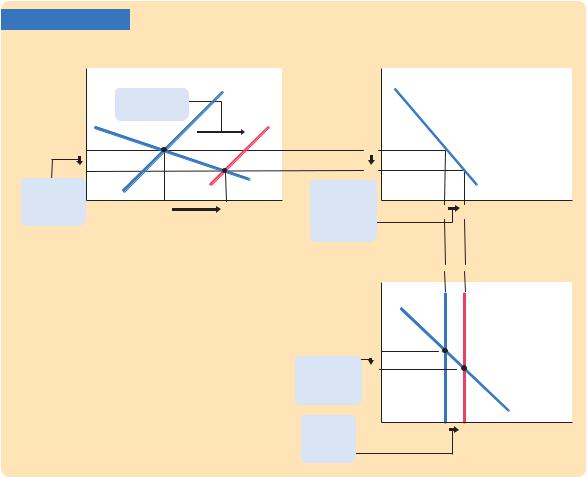

Figure 12-17 examines the effect of a monetary expansion. An increase in the money supply shifts the LM curve to the right, as in panel (a). The level of income rises, and the interest rate falls. Once again, these effects are similar to those in a closed economy.

Yet, as panel (b) shows, the lower interest rate leads to a higher net capital outflow. The increase in CF raises the supply of dollars in the market for foreign exchange. The exchange rate falls, as in panel (c). As domestic goods become cheaper relative to foreign goods, net exports rise.

FIGURE 12-17

(a) The IS–LM Model |

(b) Net Capital Outflow |

Real interest |

|

LM1 |

r |

|

|

|

rate, r |

1. A monetary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

expansion ... |

LM2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r1 |

|

|

r1 |

|

|

|

r2 |

|

IS |

r2 |

|

|

|

2. ... lowers |

|

3. ... which |

|

|

CF(r) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||

the interest |

Y1 |

Y2 Income, |

increases net |

CF1 |

CF2 |

Net capital |

rate, ... |

capital |

|||||

|

|

output, Y |

outflow, ... |

|

|

outflow, |

|

|

|

|

|

CF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Monetary Expansion in a Large Open Economy Panel (a) shows that a monetary expansion shifts the LM curve to the right. Income rises from Y1 to Y2, and the interest rate falls from r1 to r2. Panel (b) shows that the decrease in the interest rate causes the net capital outflow to increase from CF1 to CF2. Panel (c) shows that the increase

in the net capital outflow raises the net supply of dollars, which causes the exchange rate to fall from e1

to e2.

(c) The Market for Foreign Exchange

Exchange |

|

|

rate, e |

CF1 |

CF2 |

|

e1

4. ... lowers e2 the exchange rate, ...

NX(e)

5. ... and

raises net NX1 NX2 Net exports, NX exports.

C H A P T E R 1 2 The Open Economy Revisited: The Mundell-Fleming Model and the Exchange-Rate Regime | 377

We can now see that the monetary transmission mechanism works through two channels in a large open economy. As in a closed economy, a monetary expansion lowers the interest rate, which stimulates investment. As in a small open economy, a monetary expansion causes the currency to depreciate in the market for foreign exchange, which stimulates net exports. Both effects result in a higher level of aggregate income.

A Rule of Thumb

This model of the large open economy describes well the U.S. economy today. Yet it is somewhat more complicated and cumbersome than the model of the closed economy we studied in Chapters 10 and 11 and the model of the small open economy we developed in this chapter. Fortunately, there is a useful rule of thumb to help you determine how policies influence a large open economy without remembering all the details of the model: The large open economy is an average of the closed economy and the small open economy.To find how any policy will affect any variable, find the answer in the two extreme cases and take an average.

For example, how does a monetary contraction affect the interest rate and investment in the short run? In a closed economy, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. In a small open economy, neither the interest rate nor investment changes. The effect in the large open economy is an average of these two cases: a monetary contraction raises the interest rate and reduces investment, but only somewhat. The fall in the net capital outflow mitigates the rise in the interest rate and the fall in investment that would occur in a closed economy. But unlike in a small open economy, the international flow of capital is not so strong as to negate fully these effects.

This rule of thumb makes the simple models all the more valuable. Although they do not describe perfectly the world in which we live, they do provide a useful guide to the effects of economic policy.

M O R E P R O B L E M S A N D A P P L I C A T I O N S

1.Imagine that you run the central bank in a large open economy. Your goal is to stabilize income, and you adjust the money supply accordingly.

Under your policy, what happens to the money supply, the interest rate, the exchange rate, and the trade balance in response to each of the following shocks?

a.The president raises taxes to reduce the budget deficit.

b.The president restricts the import of Japanese cars.

2.Over the past several decades, investors around the world have become more willing to take advantage of opportunities in other countries. Because of this increasing sophistication, economies are more open today than in the past. Consider how this development affects the ability of monetary policy to influence the economy.

a.If investors become more willing to substitute foreign and domestic assets, what happens to the slope of the CF function?

378 | P A R T I V Business Cycle Theory: The Economy in the Short Run

b.If the CF function changes in this way, what happens to the slope of the IS curve?

c.How does this change in the IS curve affect the Fed’s ability to control the interest rate?

d.How does this change in the IS curve affect the Fed’s ability to control national income?

3.Suppose that policymakers in a large open economy want to raise the level of investment without changing aggregate income or the exchange rate.

a.Is there any combination of domestic monetary and fiscal policies that would achieve this goal?

b.Is there any combination of domestic monetary, fiscal, and trade policies that would achieve this goal?

c.Is there any combination of monetary and fiscal policies at home and abroad that would achieve this goal?

4.Suppose that a large open economy has a fixed exchange rate.

a.Describe what happens in response to a fiscal contraction, such as a tax increase. Compare your answer to the case of a small open economy.

b.Describe what happens if the central bank expands the money supply by buying bonds from the public. Compare your answer to the case of a small open economy.

C H A P T E R 13

Aggregate Supply and the

Short-Run Tradeoff Between

Inflation and Unemployment

Probably the single most important macroeconomic relationship is the Phillips curve.

—George Akerlof

There is always a temporary tradeoff between inflation and unemployment;

there is no permanent tradeoff.The temporary tradeoff comes not from inflation

per se, but from unanticipated inflation, which generally means, from a rising

rate of inflation.

—Milton Friedman

Most economists analyze short-run fluctuations in national income and the price level using the model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. In the previous three chapters, we examined aggregate demand

in some detail. The IS–LM model—together with its open-economy cousin the Mundell–Fleming model—shows how changes in monetary and fiscal policy and shocks to the money and goods markets shift the aggregate demand curve. In this chapter, we turn our attention to aggregate supply and develop theories that explain the position and slope of the aggregate supply curve.

When we introduced the aggregate supply curve in Chapter 9, we established that aggregate supply behaves differently in the short run than in the long run. In the long run, prices are flexible, and the aggregate supply curve is vertical. When the aggregate supply curve is vertical, shifts in the aggregate demand curve affect the price level, but the output of the economy remains at its natural level. By contrast, in the short run, prices are sticky, and the aggregate supply curve is not vertical. In this case, shifts in aggregate demand do cause fluctuations in output. In Chapter 9 we took a simplified view of price stickiness by drawing the short-run aggregate supply curve as a horizontal line, representing the extreme situation in which all prices are fixed. Our task now is to refine this

379

380 | P A R T I V Business Cycle Theory: The Economy in the Short Run

understanding of short-run aggregate supply to better reflect the real world in which some prices are sticky and others are not.

After examining the basic theory of the short-run aggregate supply curve, we establish a key implication. We show that this curve implies a tradeoff between two measures of economic performance—inflation and unemployment. This tradeoff, called the Phillips curve, tell us that to reduce the rate of inflation policymakers must temporarily raise unemployment, and to reduce unemployment they must accept higher inflation. As the quotation from Milton Friedman at the beginning of the chapter suggests, the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment is only temporary. One goal of this chapter is to explain why policymakers face such a tradeoff in the short run and, just as important, why they do not face it in the long run.

13-1 The Basic Theory of

Aggregate Supply

When classes in physics study balls rolling down inclined planes, they often begin by assuming away the existence of friction. This assumption makes the problem simpler and is useful in many circumstances, but no good engineer would ever take this assumption as a literal description of how the world works. Similarly, this book began with classical macroeconomic theory, but it would be a mistake to assume that this model is always true. Our job now is to look more deeply into the “frictions” of macroeconomics.

We do this by examining two prominent models of aggregate supply. In both models, some market imperfection (that is, some type of friction) causes the output of the economy to deviate from its natural level. As a result, the short-run aggregate supply curve is upward sloping rather than vertical, and shifts in the aggregate demand curve cause output to fluctuate. These temporary deviations of output from its natural level represent the booms and busts of the business cycle.

Each of the two models takes us down a different theoretical route, but each route ends up in the same place. That final destination is a short-run aggregate supply equation of the form

= − + a − a >

Y Y (P EP), 0,

−

where Y is output, Y is the natural level of output, P is the price level, and EP is the expected price level. This equation states that output deviates from its natural level when the price level deviates from the expected price level. The parameter a indicates how much output responds to unexpected changes in the price level; 1/a is the slope of the aggregate supply curve.

Each of the models tells a different story about what lies behind this short-run aggregate supply equation. In other words, each model highlights a particular reason why unexpected movements in the price level are associated with fluctuations in aggregate output.