- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Acute Renal Failure |

44 |

|

|

Raj Kumar Mani and Arghya Majumdar |

|

A 30-year-old male victim of a road trafÞc accident was admitted with pelvic fracture. An external Þxator was applied the same day. The following day he suffered a massive pulmonary embolism requiring thrombolysis. He started becoming oliguric. On the fourth day, he developed retroperitoneal hemorrhage with an intra-abdominal pressure of 22 mmHg, as a complication of anticoagulation. He required surgical drainage. He went on to develop progressive renal failure requiring dialysis support.

A systematic approach to oliguria in the ICU patient is mandatory due to the multifactorial etiology of this problem, potential to deteriorate to anuria, and need for renal replacement therapy. Timely diagnosis and prompt intervention will decrease morbidity and mortality from this potentially preventable problem. Mortality rate in patients with acute kidney injury in the ICU is in excess of 50%.

Step 1: Resuscitate

¥Optimizing oxygenation and hemodynamics is of prime importance in preventing kidney injury (refer to Chap. 78).

Step 2: Differentiate urinary retention from oliguria

¥By deÞnition, oliguria is less than 0.5 mL/kg urine output for at least 2 h.

¥Perform suprapubic percussion for bladder fullness in all cases of low urine output to exclude retention of urine.

R.K. Mani, M.D., F.R.C.P. (*)

Department of Pulmonology and Critical Care, Artemis Health Institute, Gurgaon, India e-mail: raj.rkmjs@gmail.com

A. Majumdar, M.D., M.R.C.P.

Department of Nephrology, AMRI Hospitals, Kolkata, India

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

351 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_44, © Springer India 2012 |

|

352 |

R.K. Mani and A. Majumdar |

|

|

¥Sudden drop of urine output, no urine or ßuctuating levels of urine output in a catheterized patient who is otherwise stable, may indicate a partial or complete catheter block with clot or debris or pericatheter leak. Ascertain this by physical examination, bladder wash, or replacing the catheter.

¥Bedside ultrasonography differentiates retention from oliguria and at the same time conÞrms the catheter position.

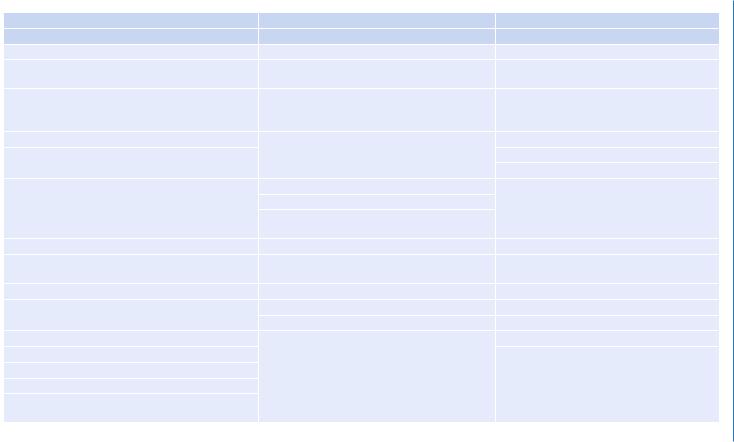

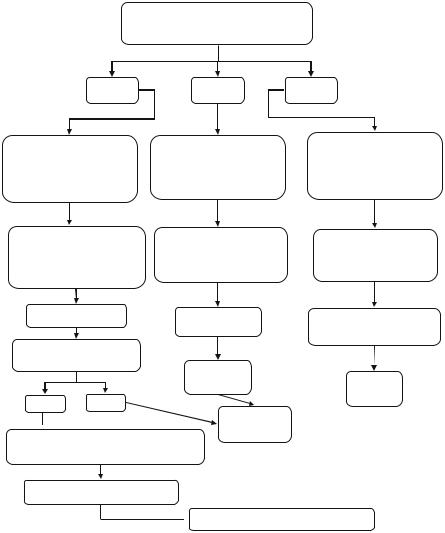

Step 3: Ascertain the cause of oliguria (Table 44.1)

¥First consider whether it is a prerenal, renal, or postrenal cause.

¥Proper history should be taken including ßuid loss, drug history (nonsteroidal anti-inßammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), exposure to contrast, urinary symptoms, and fever; perform physical examination for evidence of hypovolemia, abdominal distension, and skin rash.

¥Prerenal factors are by far the most frequent. Volume deÞcit is the commonest cause.

¥For renal factors, pay attention to the nephrotoxic potential of antibiotics, analgesic, or radiocontrast agent.

¥Postrenal factors like urethral injury and bladder outßow tract obstruction are common causes.

Step 4: Send biochemical investigations to ascertain severity and cause of acute kidney injury (AKI)

¥Serum chemistry including sodium; potassium; creatinine; blood urea nitrogen (BUN); calcium; magnesium; phosphate; uric acid; creatine phosphokinase (if rhabdomyolysis is suspected); total protein, albumin, globulin, and unconjugated bilirubin (to exclude hemolysis); and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) should be checked.

¥If clinically indicated, antinuclear factor (ANA), antiglomerular basement membrane antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), complement

levels (C3, C4), cryoglobulin, and hepatitis B and C serology test may be performed.

¥Serum and urine protein electrophoresis should be performed in patients with bone pain, hypercalcemia, and hyperglobulinemia where paraproteinemia is suspected.

Step 5: Examine the urine (Table 44.2)

¥This can yield vital clues with regard to the type of renal failure. Microscopic examination of the urinary sediment should not be neglected.

¥In prerenal failure, urine examination is usually bland, and no casts or cells will be obvious. Hyaline casts may be the only Þnding.

¥In intrinsic renal disease, one may Þnd RBC casts and dysmorphic RBCs indicating glomerular hematuria, eosinophil casts in allergic interstitial nephritis, muddy brown epithelial casts in acute tubular damage, or coarse granular or broad casts, which might indicate background chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Table 44.1 Causes of AKI |

|

|

Prerenal |

Renal |

Postrenal |

Hypovolemia |

Acute tubular necrosis |

Ureteric |

Gastrointestinal ßuid lossÑvomiting and diarrhea |

Ischemic |

Obstruction |

Renal ßuid lossÑdiuretics, osmotic diuresis |

Toxins |

External compression (retroperitoneal Þbrosis) |

(diabetes), hypoadrenalism |

|

|

Burns |

(a) Exogenous: IV contrast, antibiotics (e.g., |

Calculi |

|

aminoglycosides), CyA, chemotherapy (e.g., |

|

|

cisplatin), ethylene glycol |

|

Hemorrhage |

(b) Endogenous: Hb, myoglobin, uric acid, |

Sloughed papilla |

Sequestration in extravascular spaceÑpancreatitis, |

oxalate, myeloma |

Cancer |

trauma, and low albumin |

|

Blood clot |

|

Acute interstitial nephritis |

|

|

Idiopathic |

|

|

Infection: viral (CMV), fungal, bacterial |

|

|

(pyelonephritis) |

|

Low cardiac output states |

InÞltration: lymphoma, leukemia, sarcoid |

|

Disease of myocardium, valves, pericardium, |

Allergic drugs: antibiotics, NSAIDs, diuretics |

Bladder neck obstruction |

tamponade |

|

|

Arrhythmias |

Disease of the glomeruli |

Neurogenic |

Massive pulmonary embolus |

Acute glomerulonephritis |

Calculi |

|

Vasculitis |

Cancer |

Low renal perfusion pressure |

Hemolytic uremic syndrome, thrombotic |

Prostatic hypertrophy |

Shock (e.g., sepsis) |

thrombocytopenic purpura, disseminated |

Blood clot |

Abdominal compartment syndrome |

intravascular coagulation, preeclamptic toxemia, |

|

systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, |

|

|

Altered renalÑsystemic vascular resistance ratio |

|

|

radiation |

|

|

Systemic vasodilatationÑsepsis, antihypertensives, |

|

|

|

|

|

anesthesia |

|

|

|

|

(continued) |

Failure Renal Acute 44

353

Table 44.1 (continued) |

|

354 |

|

|

|

Prerenal |

Renal |

Postrenal |

Hypovolemia |

Acute tubular necrosis |

Ureteric |

|

Renovascular |

|

|

Renal veinÑthrombosis |

Urethral obstruction |

|

Renal arteryÑstenosis, plaque, embolism, |

Stricture |

|

thrombus, aneurysm |

|

|

Intratubular deposition and obstruction |

Congenital valves |

Renal vasoconstriction |

Myeloma proteins |

Phimosis |

Hypercalcemia |

Uric acid |

|

Norepinephrine, vasopressor agents |

Oxalate |

|

CyA, tacrolimus |

Acyclovir crystals |

|

Cirrhosis with hepatorenal syndrome |

Methotrexate |

|

Hyperviscosity |

Sulfonamides |

|

Multiple myeloma |

Renal allograft rejection |

|

Macroglobulinemia |

|

|

Majumdar .A and Mani .K.R

44 Acute Renal Failure |

|

355 |

|

|

|

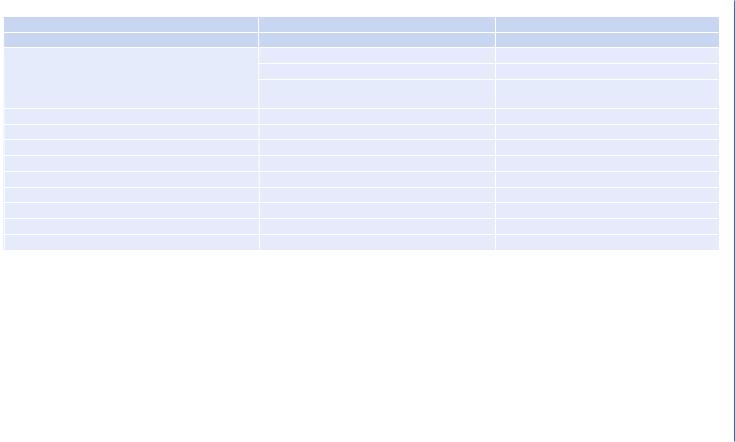

Table 44.2 Urinary biochemistry |

|

|

|

Prerenal |

Renal |

Urine osmolality |

>500 mosmols/kg |

<350 mosmols/kg |

Urine sodium |

<10 mEq/L |

>20 mEq/L |

Urine/plasma osmolality ratio |

>1.5 |

<1.2 |

Urine/plasma urea nitrogen ratio |

>8 |

<3 |

Urine/plasma creatinine ratio |

>40 |

<20 |

Plasma BUN/creatinine ratio |

>20 |

<10 |

Urine speciÞc gravity |

>1.020 |

~1.010 |

Fractional excretion of sodium (FeNa)% |

<1 |

>1 |

Urine/plasma Na divided by urine/plasma |

|

|

creatinine × 100 |

|

|

¥Uric acid or calcium oxalate crystals may highlight a background metabolic problem.

¥RBC and WBC casts are fragile, and their absence does not exclude underlying parenchymal disease.

¥Dipstick test is vital. It might reveal proteinuria, hematuria, glycosuria, ketonuria, bilirubin, or urobilinogen. A positive dipstick for hemoglobin in the absence of RBCs in the urine sediment may suggest hemolysis or myoglobinuria (which can be conÞrmed by speciÞc assays).

¥A positive nitrite test may indicate infection. High speciÞc gravity and ascorbic acid may interfere with the test.

¥Urine biochemistry test should be performed to differentiate prerenal from renal failure (Table 44.2).

Step 6: Monitor the patient carefully

¥Ensure continuous monitoring of urine output, by placing an indwelling urinary catheter.

¥Continuous monitoring of hemodynamic parameters is also mandatory.

¥Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) monitoring is very important, especially when large volumes of ßuids or blood products are infused, as they may third space into the peritoneal cavity if there is capillary leak due to systemic inßammatory response syndrome (SIRS) after trauma, sepsis, or abdominal surgery.

¥IAP of less than 12 mmHg indicates normal condition, 12Ð20 mmHg indicates intra-abdominal hypertension, and more than 20 mmHg with organ dysfunction indicates abdominal compartment syndrome.

Step 7: Perform renal imaging

¥Abdominal ultrasound or noncontrast CT scan would be useful to diagnose renal and postrenal oliguria.

¥An ultrasonography may reveal echogenic or small kidneys with loss of corticomedullary differentiation, which might indicate a background of chronic kidney disease. However, in some conditions such as diabetes, amyloidosis, and multiple myeloma, kidney size may be normal even with chronic disease. A

356 |

R.K. Mani and A. Majumdar |

|

|

discrepancy in kidney size (>2 cm) may suggest unilateral renal artery stenosis. Color Doppler ßow can be used to assess renal perfusion and rule out thrombosis. Multiple bilateral cortical cysts may indicate polycystic kidney disease.

¥The presence of hydronephrosis and/or hydroureter is suggestive of a postrenal cause. However, a dehydrated patient may not exhibit signiÞcant hydronephrosis. Postvoidal residual urine of more than 100 mL is suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction.

¥Volume status can be assessed by checking the diameter and collapsibility of the inferior vena cava.

¥Radiologic examination is useful for detecting renal stones and pelvic fractures. However, fecoliths may masquerade as stones, and without proper bowel preparation, it is difÞcult to delineate stones.

¥Occasionally an intravenous urogram, contrast CT (if renal function is normal), MRI, or retrograde/antegrade (percutaneous) contrast studies may be necessary to delineate the site or nature of obstruction or injury.

¥Nuclear scans may be used to assess renal function, perfusion, or obstruction.

Step 8: Be wary of sepsis

¥Always suspect sepsis, whether as the primary cause or as an intercurrent complication. In such instances, the promptness and appropriateness of antibiotics can save lives.

¥In case of postrenal oliguria and urosepsis, urgent urological intervention such as urinary drainage using ureteric catheterization, DJ stents, or percutaneous nephrostomy may be required, as source control is vital. Perinephric collections of pus or blood may need drainage too (Fig. 44.1).

Step 9: Maintain renal perfusion pressure

¥Maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) of more than 65 mmHg by adequate volume loading and with vasopressors if necessary. MAP may have to be kept higher if the patient is hypertensive or has a high IAP.

¥Individual titration is necessary in this regard. In cases of high IAP, renal perfusion pressure is equal to MAPÐ2 × IAP, and a higher MAP is desirable. Dose of vasopressors should be kept to minimum, which is necessary for maintaining an adequate MAP, and every attempt should be made to reduce dose of vasopressors.

¥Invasive hemodynamic monitoring (arterial line and central line) is usually needed in these cases.

¥There is no role of renal dose of dopamine to increase renal perfusion.

¥Dobutamine should be used to optimize cardiac output, provided there is no tachycardia or arrhythmia (refer to Chap. 18).

¥Occasionally one may have to take recourse to an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) for hemodynamic optimization in cardiogenic shock.

¥Medical (e.g., diuresis, drainage of ascites) and surgical measures (e.g., opening up of abdominal sutures) should be taken up, where possible, to reduce intraabdominal hypertension.

44 Acute Renal Failure |

357 |

|

|

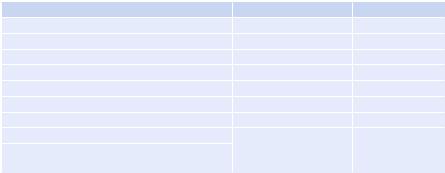

Urine output <0.5 mL/kg/h × 2 hours

|

Prerenal |

Renal |

Postrenal |

|

History/exam (fluid loss, |

History/exam (renovascular, |

History/exam (Ureteric |

||

sequestration, ↓ Cardiac |

||||

obstruction, clot, stone, |

||||

Output, sepsis, hepatorenal |

glomerular, ATN, AIN) |

|||

urethral obstruction) |

||||

drugs, hyperviscosity) |

|

|||

|

|

|||

Hemodynamic |

Urinalysis (casts, crystals, |

Urinalysis (clots, crystals, |

||

assessment/fluid |

||||

responsiveness (CVP, |

proteinuria, myoglobinuria, |

sloughed papilla, |

||

PCWP, PLR, Echo), SVV, |

eosinophiluria, etc.) |

malignant cells) |

||

PICCO, etc.) |

|

|

||

Urine analysis |

Renal biopsy |

Imaging (CT, MRU, RGP); |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Urodynamic study |

|

Na <10 mmol/L, |

|

|

||

SG >1.018, Fe Na <1% |

Checklist of |

|

||

|

|

Checklist |

||

|

|

causes |

||

Yes |

No |

|

of causes |

|

|

|

|||

Consider

intrinsic renal Further fluid challenge and hemodynamic

intrinsic renal Further fluid challenge and hemodynamic

reassessment for fluid responsiveness

Oliguria despite adequate filling

Consider Intra-abdominal hypertension

Consider Intra-abdominal hypertension

Fig. 44.1 Approach to oliguria

Step 10: Use diuretics judiciously

¥Weigh the potential beneÞts versus risks of a trial of intravenous diuretics. The role of diuretic therapy has been questioned as it does not affect renal outcome. However, in nonoliguric renal failure, management of the patient becomes easier. It creates some intravascular space for administering nutrition, intravenous antibiotics, blood, and blood products, where necessary.

However, diuretics have been shown to be detrimental too. They create an acidic

urine milieu, which might predispose to myoglobin precipitation and oxalate crystallization. The potential toxicities of diuretics include worsening of hypovolemia,

358 |

R.K. Mani and A. Majumdar |

|

|

metabolic alkalosis, and interstitial nephritis. Further, a diuretic response may delay a search for correctable causes of oliguria.

Step 11: Correct metabolic abnormalities

¥Look for and manage metabolic abnormalities, which may be a result of renal impairment such as hyperkalemia, hyper/hyponatremia, and hypocalcemia.

¥Look for causative factors such as hypercalcemia or hyperuricemia.

¥Frequent monitoring of electrolytes may be necessary.

¥The usual ureaÐcreatinine ratio is 10:1. An unusually high ureaÐcreatinine ratio is suggestive of volume depletion, gastrointestinal bleeding, catabolic state, or high protein feed.

¥A high creatinineÐurea ratio is associated with rhabdomyolysis or may indicate chronic kidney disease (CKD).

¥If rhabdomyolysis is suspected, the maintenance of urinary pH to more than 7 by systemic alkalinization is indicated.

Step 12: Avoid any potentially nephrotoxic agent

¥In high-risk cases, along with hydration with 0.9% saline, N-acetyl cysteine at a dose of 600 mg twice per day may be administered for 3 days from a day prior to elective radiocontrast imaging study.

¥Low osmolality or preferably iso-osmolar contrast should be used.

¥Avoid nephrotoxic antibiotics. Aminoglycosides, if used, should be dosed once daily.

¥Lipid formulations of amphotericin are preferable.

¥Intravenous use of voriconazole may cause nephrotoxicity due to b-cyclodextrin.

¥Intravenous acyclovir may cause crystal nephropathy.

¥High-dose mannitol may lead to osmotic nephropathy.

¥NSAIDs should be avoided.

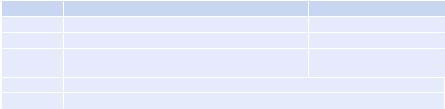

Step 13: Strive to detect acute kidney injury (AKI) as early as possible (Table 44.3)

¥The Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) group, composed of nephrologists and intensivists, has laid down deÞnitive criteria for diagnosing AKI, which has been universally accepted and validated.

¥This is the RIFLE criteria (risk, injury, failure, loss, end-stage kidney disease), which should now be followed in all ICUs to stratify AKI.

Table 44.3 |

RIFLE criteria |

|

Category |

Glomerular Þltration rate (GFR) criteria |

Urine output (UO) criteria |

Risk |

Increased creatinine × 1.5 or GFR decrease >25% |

UO <0.5 mL/kg/h × 6 h |

Injury |

Increased creatinine × 2 or GFR decrease >50% |

UO <0.5 mL/kg/h × 12 h |

Failure |

Increased creatinine × 3 or GFR decrease >75% |

UO <0.3 mL/kg/h × 24 h or |

|

|

anuria × 12 h |

Loss |

Persistent acute renal failure = complete loss of kidney function in >4 weeks |

|

ESKD |

End-stage kidney disease (>3 months) |

|