- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

590 |

R. Chawla and P. Nasa |

|

|

•Manage complications:

–Renal failure

–Acute pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome

–Coagulopathy/disseminated intravascular coagulation

•Rarely, liver transplantation is indicated for liver rupture with necrosis, fulminant liver failure, hepatic encephalopathy, or worsening coagulopathy.

B.Hyperemesis gravidarum

•Treatment is supportive and includes intravenous rehydration and antiemetics.

•Vitamin supplementation, including thiamine, is mandatory to prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

•There is no role of steroids.

•Relapse and recurrence in subsequent pregnancies is common.

C.Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

•Treatment of choice is ursodeoxycholic acid, which helps to relieve pruritis and improve hepatitis.

•Mechanism of action is unknown.

•Other drugs are cholestyramine, dexamethasone, and vitamin K supplementation.

•Termination of pregnancy—when medical measures fail or if the patient’s condition deteriorates.

D.Management of severe preeclampsia–eclampsia and HELLP syndrome (discussed in Chap. 75)

•Treatment of hepatic rupture should be delegated to a surgeon experienced in the management of hepatobiliary surgeries.

E.Viral hepatitis

•Treatment is mainly supportive and similar to nonpregnant patients.

•Course is not altered by delivery.

•Herpes simplex hepatitis can be effectively treated with acyclovir if the diagnosis is recognized promptly.

Suggested Reading

1.Matin A, Sass DA. Liver disease in pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2011;40:335–53.

This article briefly discusses gestational physiologic changes and thereafter reviews liver diseases during pregnancy.

2.Joshi D, James A, Quaglia A, Westbrook RH, Heneghan MA. Liver disease in pregnancy. Lancet. 2010;375:594–605.

This article gives an overview of the management of liver diseases in pregnancy.

3.Lee NM, Brady CW. Liver disease in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:897–906.

This article reviews the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of liver diseases seen in pregnancy.

4.Hay JE. Liver disease in pregnancy. Hepatology. 2008; 47:1067–76.

This article reviews the various liver diseases that are complicated by pregnancy and are specifically associated with pregnancy.

Acute Respiratory Failure During |

74 |

Pregnancy |

Rajesh Chawla, Prashant Nasa, and Aakanksha Chawla

A 25-year-old female at 36 weeks of pregnancy was admitted to hospital with complaints of breathlessness, right sided chest pain, and swelling of the left leg for 3–4 days. Her BMI was 40 kg/m2. She was tachypneic, chest was clear, and SpO2 on room air was 90%.

Acute respiratory failure during pregnancy can occur due to many disorders. It can result in significant maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

Step 1: Initiate assessment and resuscitation

Airway

•Airway evaluation and management remains the first priority in the initial resuscitation as in nonpregnant patients.

•Definitive airway (tracheal intubation) is needed in persistent hypoxemia, airway obstruction, impaired laryngeal reflexes, or in altered consciousness.

•Difficult airway equipment for airway management must be thoroughly checked before proceeding to intubation, and an alternative plan for definitive airway including surgical access should be identified.

•Intubation should be performed by a senior intensivist/anesthesiologist especially in later part of pregnancy due to upper airway edema and narrow airway caliber.

R. Chawla, M.D., F.C.C.M. (*)

Department of Respiratory, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine, Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals, New Delhi, India

e-mail: drchawla@hotmail.com

P. Nasa, M.D., F.N.B.

Department of Critical Care Medicine, Max Superspeciality Hospital, New Delhi, India

A. Chawla, M.B.B.S.

B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Nepal

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

591 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_74, © Springer India 2012 |

|

592 |

R. Chawla et al. |

|

|

Breathing

•Supplemental oxygen may be required in some patients depending on their oxygen saturation.

•Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) can be tried only in the controlled ICU setting. Signs of failure of NIV and requirement of intubation should also be identified sooner than later. This includes increased work of breathing, mental status deterioration, hemodynamic instability, and inability to protect the airway or manage secretions.

•Always target SpO2 of more than 95%. For adequate fetal oxygenation, a maternal arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) of more than 70 mmHg is required, which corresponds to an oxyhemoglobin saturation of 95%.

Circulation

•Two large-bore intravenous cannulae (14G or 16G) should be placed to administer fluids.

•Administrate fluid judiciously to optimize preload and at the same time to avoid overload.

•Maintain high cardiac output.

•Nursing in the left lateral (30° wedge to the right hip) position is needed to prevent supine hypotension syndrome.

Step 2: Take history and physical examination

•Take detailed history of pregnancy, antenatal evaluation and immunization, respiratory disease (e.g., asthma and tuberculosis), and family history of active respiratory infections.

•Detailed history of respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, expectoration, and chest pain should be evaluated.

•The physical examination includes assessment of the severity of respiratory failure by general assessment, respiratory rate, use of accessory respiratory muscles, and signs of impending respiratory arrest (e.g., fatigue, drowsy, silent chest, and bradycardia).

•Assessment of the fetus is also important. Fetal heart sounds and its variability— to ascertain the fetal well-being—should be assessed along with the maternal assessment.

Step 3: Understand physiological changes in pregnancy

•Pregnancy causes various mechanical, immunological, biochemical, and hemodynamic changes on the cardiorespiratory system (Table 74.1).

•Normal PaCO2 on ABG should be interpreted as a sign of impending respiratory failure as there is a mild respiratory alkalosis in pregnancy (see Table 74.1).

•Inability to maintain a PaO2 of more than 70 mmHg, or a SaO2 of more than 95%, with conservative therapy should also be interpreted as a sign of respiratory compromise.

74 Acute Respiratory Failure During Pregnancy |

593 |

|

|

||

Table 74.1 Effects of pregnancy on pulmonary physiology |

||

|

Anatomical changes |

Physiological alterations |

Airway |

Edema, mucosal friability, |

Increased respiratory drive |

|

rhinitis |

Hyperventilation |

Thorax including |

Widened diameters, widened |

Reduced functional residual capacity |

lung parenchyma |

subcostal angle, elevated |

Increased tidal volume |

|

diaphragm |

Preserved vital capacity |

|

|

|

|

|

Respiratory alkalosis |

|

|

Normal oxygenation |

Abdomen |

Enlarged uterus |

Reduced chest wall compliance |

Cardiovascular |

Increased left ventricular (LV) |

Increased cardiac output |

system |

mass |

|

|

Increased blood volume |

|

Arterial blood gas |

|

7.40–7.45 pH |

|

|

28–32 mmHg PaCO2 |

|

|

106–110 mmHg PaO2 |

Step 4: Send investigations

•Complete hemogram.

•Liver function tests.

•Renal function tests and serum electrolytes.

•Arterial blood gas.

•Coagulation profile (prothrombin time [PT], activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT], and fibrinogen international normalized ratio).

•Sputum examination/tracheal secretions—Gram stain and aerobic culture sensitivity.

•Paired percutaneous blood cultures.

•Additional tests if indicated—D-dimer does not help in pregnancy.

•Chest X-ray only if absolutely necessary.

•Multidetector computed tomographic (MDCT) pulmonary angiography if clinical situation demands.

•Ultrasonography is used to assess the status of the fetus, to evaluate growth, and in suspected case to evaluate deep venous thrombosis.

•Transthoracic echocardiography

Step 5: Make a diagnosis of respiratory failure in pregnancy

The various causes of acute respiratory failure are summarized in Table 74.2.

A.ARDS

•The criteria for diagnosis of ARDS are similar to nonpregnant women (see Chap. 5).

B.Asthma in pregnancy

•Rule of thirds—one-third of patients with asthma in pregnancy improve, and one-third shows no change. One-third worsens and can present in acute severe asthma.

•This explains the unpredictable effect of pregnancy on asthma.

594 |

|

R. Chawla et al. |

|

||

Table 74.2 Differential diagnosis of acute respiratory failure during pregnancy |

||

|

Conditions can be affected |

Conditions unaffected |

Conditions unique to pregnancy |

by pregnancy |

by pregnancy |

Peripartum cardiomyopathy |

Acute pulmonary edema |

ARDS—direct/pulmonary |

|

|

Bacterial pneumonia |

Amniotic fluid embolism |

Aspiration of gastric |

Fat embolism |

|

contents |

|

Tocolytic therapy-induced acute |

Asthma |

Inhalational injury |

pulmonary edema |

|

|

Severe preeclampsia |

Venous thromboembolism |

Indirect |

Chorioamnionitis, endometritis |

Bacterial and viral |

Sepsis, trauma, burns |

|

pneumonia |

|

Ovarian hyperstimulation |

Malaria, fungal infections |

Acute pancreatitis, |

syndrome (OHSS) |

|

transfusion-related acute |

|

|

lung injury (TRALI) |

C.Pulmonary embolism in pregnancy

•Pregnancy itself is a hypercoagulable state and an independent risk factor for pulmonary embolism (PE).

•Clinical prediction models that are used to predict pretest probability of PE have not been validated in pregnant patients.

•D-dimers are likely to perform differently in the pregnant population as D-dimers may be falsely high in pregnant patients.

•Radiographic imaging remains the primary testing modality for diagnosing PE, and it should not be delayed because of concerns about radiation exposure.

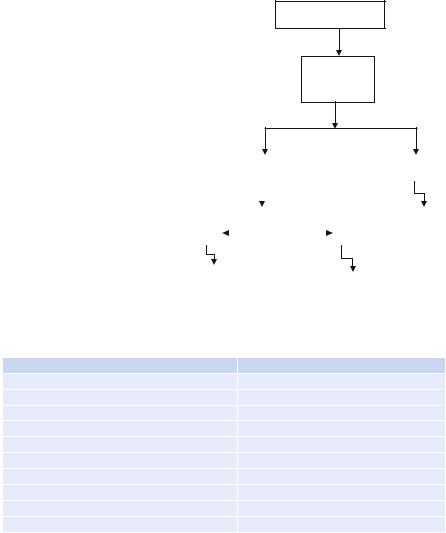

•Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) pulmonary angiography is currently the most preferred mode for confirming diagnosing PE in pregnant patients (Fig. 74.1).

•The main concerns with MDCT are radiation and contrast exposure to the fetus in suspected PE. It has been seen that the exposure of radiation is less to the fetus.

•Compression ultrasonography and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are the initial test of choice to exclude deep venous thrombosis.

•Chest radiographs involve minimal radiation; they rarely show signs suggestive of PE, which may detect other diagnosis.

•The accuracy of ventilation-perfusion scan in pregnancy is not available, and outcome studies are limited.

D.Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)

•Gestation of 3–8 weeks.

•Increased vascular permeability—fluid shift from the intravascular to extravascular space—causing pleural or pericardial effusions, ascites, electrolyte imbalances, dyspnea, oliguria, severely enlarged polycystic ovaries, hemoconcentration, and hypercoagulability, electrolyte imbalance are the common presentations.

74 Acute Respiratory Failure During Pregnancy |

595 |

|

|

Fig. 74.1 Diagnosis of PE

Suspected PE

Signs of

DVT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

CUS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MDCT |

||

Pos |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Negative |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

PE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MDCT |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

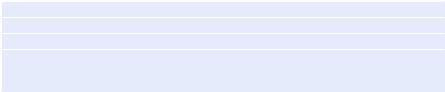

Table 74.3 Criteria that define the severe and life-threatening stages of OHSS

Severe OHSS |

Life-threatening OHSS |

Variably enlarged ovary |

Variably enlarged ovary |

Massive ascites with or without hydrothorax |

Tense ascites with or without hydrothorax |

Hematocrit >45% |

Hematocrit >55% |

WBC count >15,000 |

WBC count >25,000 |

Oliguria |

Oliguria |

Creatinine level 1.0–1.5 mg/dL |

Creatinine level ³1.6 mg/dL |

Creatinine clearance ³50 mL/min |

Creatinine clearance <50 mL/min |

Liver dysfunction |

Renal failure |

Anasarca |

Thromboembolic phenomena |

|

ARDS |

•The common criteria for severe and life-threatening OHSS are described in Table 74.3.

E.Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM)

•Risk factors include hypertension, preeclampsia, multiparity, multiple gestations, and older maternal age.

•Signs and symptoms are paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, chest pain, nocturnal cough, new regurgitant murmurs, pulmonary crackles, increased jugular venous pressure, and hepatomegaly.

•Identify other cardiac and noncardiac disorders such as coronary, rheumatic, or valvular heart disease; arrhythmias; and family history of cardiomyopathy

596 |

R. Chawla et al. |

|

|

Table 74.4 Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of PPCM

Development of cardiac failure in the last month of pregnancy or within 5 months postpartum

Absence of another identifiable cause for the cardiac failure

Absence of recognizable heart disease before the last month of pregnancy

LV systolic dysfunction shown by echocardiographic data such as depressed shortening fraction (e.g., ejection fraction less than 45%, M-mode fractional shortening less than 30%, or both, and an LV end diastolic dimension of more than 2.7 cm/m2)

or sudden death and other risk factors of cardiac diseases such as hypertension (chronic, gestational, preeclampsia), diabetes, dyslipidemia, thyroid disease, anemia, prior chemotherapy or mediastinal radiation, sleep disorders, current or past alcohol or drug abuse, and collagen vascular disease.

•The diagnosis of PPCM is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be made when other possible causes of acute/subacute heart failure have been ruled out (Table 74.4).

Step 6: Treat the specific cause

The general management of respiratory failure in pregnancy is similar to the management in nonpregnant women, although one should be careful about normal physiologic alterations that occur in the parturient state and effect of ventilator strategies.

A.Management of ARDS and mechanical ventilation in pregnant patients

•Lung-protective strategy to avoid volutrauma, biotrauma, atelectrauma, leading to less ventilator-induced lung injury has been found to reduce mortality and improve outcome in patients with ARDS.

•Lung-protective strategy causes hypoventilation, which is tolerated to maintain (permissive hypercapnia) the pH between 7.25 and 7.35.

•Permissive hypercapnia can cause fetal acidosis, an increase in intracranial pressure, and a right shift in the hemoglobin dissociation curve and in first 72 h may lead to retinopathy of prematurity, so lung-protective ventilatory strategy in pregnant patients should be used with close monitoring of the fetal status with the biophysical profile.

•Oxygen levels should be closely monitored in pregnancy and kept higher than in nonpregnant women (preferably SpO2 ³ 95%).

B.Management of asthma in pregnancy

•Management of asthma in pregnancy is similar to nonpregnant women.

•Beta-agonists bronchodilators and corticosteroids are the mainstay of the treatment.

C.PE during pregnancy

•Acute treatment of PE can be done with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH) and should be started without delay whenever PE is suspected or confirmed.

•LMWH is first-line therapy for the treatment of acute PE in the general population and in pregnancy as the risk of bleeding in pregnant women is not different from nonpregnant women.

74 Acute Respiratory Failure During Pregnancy |

597 |

|

|

•Thrombolysis increases the risk of obstetric and neonatal complications such as pregnancy loss, abruption, and preterm labor. Therefore, the use of thrombolytics in pregnancy should be reserved for women with PE who are hemodynamically unstable or with refractory hypoxemia.

•The American College of Chest Physicians guideline recommends the use of anticoagulation for 6 months at least in the postpartum period.

•Always give injectable heparins during the entire period of pregnancy. Start oral anticoagulants only after delivery.

D.OHSS

•Syndrome is self-limiting, and resolution parallels the decline in serum HCG levels: 7 days in nonpregnant patients and 10–20 days in pregnant patients.

•Monitor frequently for deterioration with physical examinations, daily weights, and periodic laboratory measurements of complete blood counts, electrolytes, and analysis of renal and hepatic function.

•Severe disease—placement of two large-bore peripheral intravenous catheters or a central venous catheter (preferred) for fluid management may be required.

•Use the Foley’s catheter for close monitoring of the urine output.

•Normal saline with or without glucose is the crystalloid of choice, and potas- sium-containing fluids should be avoided because patients with OHSS could develop hyperkalemia.

•In more severe cases with significant hypovolemia, hemoconcentration (hematocrit >45%), hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin level <3.0 g/dL), or severe ascites, albumin can be given as a plasma expander along with diuretics (furosemide) once hematocrit is 36–38%.

•If respiratory symptoms worsen, thoracentesis/paracentesis should be performed.

•If ARDS develops and mechanical ventilation is required, lung-protective strategies must be used.

E.PPCM

•Diuretics are indicated for most patients because they cause symptomatic relief of pulmonary and peripheral edema and are usually used as adjuvant to other definitive therapies. Furosemide is the most commonly used diuretic.

•Aldosterone antagonists have been shown to improve survival in selected heart failure patients. These agents are still not advised in pregnancy (lack of safety data); however, they can be added postpartum.

•Hydralazine and nitrates are the vasodilators of choice for pregnant women, as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, the first-line agent for nonpregnant patients, are contraindicated for pregnant women.

•b-Blockers (sustained-release metoprolol succinate, carvedilol, and bisoprolol) have been shown to reduce mortality with current or prior heart failure and reduced ejection fraction and therefore constitute the first-line therapy for all stable patients unless contraindicated (Table 74.5).

•Digoxin improves symptoms, quality of life, and improves exercise tolerance in mild-to-moderate heart failure.