- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Nutrition Support |

43 |

|

|

Pravin Amin |

|

A 25-year-old male patient (175 cm in height and 80 kg in weight), involved in a motorcycle accident, was admitted to the ICU. He had several high rib fractures and a ßail segment on his left chest wall with associated major lung contusion and hemopneumothorax on the left side. He had blunt injury to abdomen with large bruises in the epigastrium. He had fractured both tibia and femur in the right lower limb. His blood pressure on arrival was 70/40 mmHg, heart rate was 145/min, and respiratory rate was 42/min. He was fully conscious but in distress. You had been asked to formulate a nutritional plan for him.

Nutritional support is an integral part of organ support in the ICU. A systematic and protocolized approach to nutrition support by a dedicated nutrition support team is ideal to minimize complications of the ICU stay.

Step 1: Initial resuscitation

¥Achieving hemodynamic stability is of paramount importance before considering nutritional support. Nutrition should be started as soon as the patient is resuscitated.

Step 2: Assess nutritional status

¥Initial assessment of nutritional status is important as many patients are malnourished on admission and require early nutritional support.

¥Traditional methods of nutritional assessment like calculation of body mass

index = weight (kg)/height (m2). AnthropometryÑtriceps skinfold, mid-arm

P. Amin, M.D., F.C.C.M. (*)

Department of Internal Medicine and critical care Bombay Hospital Institute of Medical Sciences, Mumbai e-mail: pamin@vsnl.com

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

341 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_43, © Springer India 2012 |

|

342 |

P. Amin |

|

|

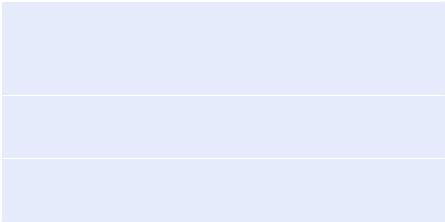

Table 43.1 Subjective global assessment of nutritional status

(A)History

1.Weight change

2.Dietary intake change relative to normal

3.Gastrointestinal symptoms (persisting for more than 2 weeks)

4.Functional capacity

5.Disease and its relationship to nutritional requirements

(B)Physical examination (for each specify: 0 = normal, 1 + = mild, 2 + = moderate, 3 + = severe) Loss of subcutaneous fat (triceps, chest)

Muscle wasting (quadriceps, deltoids) Ankle edema/sacral edema/ascites

(C)Subjective global assessment rating Well nourished

Moderately malnourished Severely malnourished

muscle circumference, and creatinine-height index. Laboratory assessmentÑ albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, serum cholesterol, and C-reactive protein are not very reliable in critically ill patients.

¥Bedside clinical assessment by Òeye ballingÓ and subjective global assessment by history and simple physical examination are more reliable (Table 43.1).

Step 3: Calculate ideal (predicted) body weight

¥In most critically ill patients, body weight cannot be measured, and ideal (predicted) body weight (IBW) needs to be calculated by height. Most of the nutritional formulae are based on ideal body weight:

ÐMale IBW (kg) = 50 + (0.91 × (height in centimeters − 152.4)) or 50 kg for 5 ft, add 2.3 kg for every 1 in. above 5 ft.

ÐFemale IBW (kg) = 45.5 + (0.91 × (height in centimeters − 152.4)) or 45.5 kg for 5 ft, add 2.3 kg for every 1 in. above 5 ft.

Step 4: Estimate energy (calories) requirement

¥Rule of the ÒthumbÓ: 25Ð30 kcal/kg IBW meets most patientsÕ needs.

¥In undernourished patients, initial calorie should be 25% less than IBW to prevent refeeding, and in overweight patients, initial calorie should be 25% more than IBW to meet requirement.

¥In a malnourished patient, a large glucose and calorie load can cause a massive shift of potassium, phosphate, and magnesium to intracellular compartment, leading to a precipitous fall of these electrolytes in the plasma, resulting in cardiorespiratory failure. This phenomenon is called refeeding syndrome. Phosphate, magnesium, and potassium should be checked and adequately replaced, and calories and glucose load should be gradually increased in such patients.

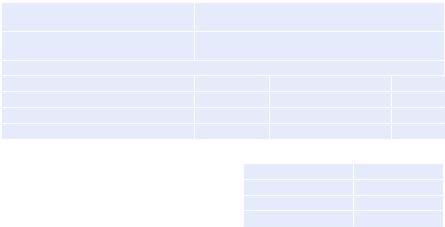

¥Formulas like HarrisÐBenedict may be used to calculate calorie requirement, but are time-consuming and not validated in critically ill patients (Table 43.2).

43 Nutrition Support |

|

|

343 |

|

|

||

Table 43.2 HarrisÐBenedict equation with LongÕs modiÞcation |

|

||

HarrisÐBenedict formula for women |

Basal metabolic rate (BMR) = 655 + (9.6 × weight |

||

|

in kg) + (1.8 × height in cm) − (4.7 × age in years) |

||

HarrisÐBenedict formula for men |

BMR = 66 + (13.7 × weight in kg) + (5 × height |

||

|

in cm) − (6.8 × age in years) |

|

|

Actual energy needs = BMR × AF × IF |

|

|

|

Activity factor (AF) |

Use |

Injury factor (IF) |

Use |

ConÞned to bed |

1.2 |

Minor surgery |

1.2 |

Out of bed |

1.3 |

Skeletal trauma |

1.3 |

|

|

Major sepsis |

1.6 |

Table 43.3 Protein |

|

No stress |

0.7Ð0.8 g/kg/day |

requirements |

|

Mild stress |

0.8Ð1.0 g/kg/day |

|

|

||

|

|

Moderate stress |

1.0Ð1.5 g/kg/day |

|

|

Severe stress |

1.5Ð2.0 g/kg/day |

¥Carbohydrates usually form 70Ð75% of calories. Fats usually form 25Ð30% of calories, not more than 40Ð50%.

¥Protein intake should not be calculated as a calorie source.

¥Indirect calorimetry may be used for calorie calculation and measuring respiratory quotient. A high respiratory quotient of more than 1 indicates carbohydrate as a predominant source of energy. It cannot be used in patients requiring high inspired oxygen, air leaks, or chest tubes.

Step 5: Estimate protein (nitrogen) requirement

¥Rule of the ÒthumbÓ: 1.5Ð2 g of protein/kg IBW meets most patientsÕ needs (Table 43.3):

Ð 6.25 g of protein is equal to 1 g of nitrogen.

Ð Non Protein Calorie (NPC)Ðnitrogen ratio = 150 cal (NPC): 1 g nitrogen.

¥Nitrogen requirement may also be assessed by calculating nitrogen balance:

ÐNitrogen balance = nitrogen intake − nitrogen output.

ÐNitrogen intake = protein intake/6.25.

ÐNitrogen output = 24-h urinary urea nitrogen + 4 (nonurinary nitrogen).

ÐThis should be done once weekly in all severely ill patients with a normal renal function. Try to achieve at least equal nitrogen balance.

Step 6: Supplement micronutrients

¥Vitamins and the trace of elements should be added as per recommended daily allowance, which are present in formula feed.

Step 7: Estimate fluid and electrolyte requirement

¥Rule of the ÒthumbÓ: 1 ml/cal is the minimum requirement of ßuid to deliver isocaloric feed.

¥Electrolyte should be tailored to individual patientsÕ requirement.

344 |

P. Amin |

|

|

Step 8: Select route of delivering nutrition

¥Whenever the gut is working, use it. Advantages of enteral feed are as follows:

ÐPreservation of the integrity and function of the gastrointestinal tract

ÐMaintenance of splanchnic blood ßow

ÐProvision of nutrition to the enterocytes

ÐFewer infectious and metabolic complications

ÐEase of administration, lower costs, and avoiding the disadvantages of total parenteral nutrition (TPN)

¥Enteral feeding may be given through nasogastric, nasojejunal, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy tubes. There is no signiÞcant difference in the efÞcacy of jejunal versus gastric feeding in critically ill patients.

¥Intragastric feeding should be the Þrst choice because it is easy and relatively safe, and the majority of patients tolerate it:

ÐThe head of the bed should be elevated to 30Ð45¡.

ÐGive continuous rather than bolus feedings; start with 25 cc intragastrically every hour to a target rate of 50Ð75 cc/h, in most adults preferably through a feeding pump.

ÐCheck residual 2 h after initiating feeding and every 8 h thereafter.

ÐIV administration of metoclopramide should be considered in patients with intolerance to enteral feeding, for example, with high gastric residuals (>300 in 4 h or more than one-third of enteral feed being aspirated).

¥Jejunal feed can be tried if the patient has high gastric residue despite prokinetic and correction of electrolytes.

Step 9: Select the type of enteral feed

¥Blenderized diets: It may not be complete and balanced. Nutritive value is difÞcult to estimate, and highly viscous solution needs a large-bore nasogastric tube. Large particles may block the feeding tubes, and nutrients are not predigested. Bacterial overgrowth is a distinct possibility.

¥Polymeric diets: These contain nitrogen as whole protein and are balanced and compete. The carbohydrate source is partially hydrolyzed starch, and the fat contains long-chain triglycerides. Their Þber content is very variable.

¥Predigested diets: These feeds contain nitrogen either as short peptides or, in the case of elemental diets, as free amino acids. Carbohydrate provides much of the energy. The rest of the calorie proportion is provided as long-chain triglycerides and medium-chain triglycerides. The aim of Òpredigested dietsÓ is to improve nutrient absorption in the presence of signiÞcant malabsorption.

¥Disease-speciÞc diets: Patients with respiratory failure are often given feeds with a low carbohydrate-to-fat ratio to minimize carbon dioxide production. Renal patients often require modiÞed protein, electrolyte, and volume feeds. Liver patients may need low sodium, low volume feeds. There is no good evidence that patients with hepatic encephalopathy should have low protein intakes, and the evidence for the beneÞt of feeds rich in branched-chain amino acids is weak.

¥Immunonutrition: Glutamine should be added to a standard enteral formula in burned patients and trauma patients. The immune-modulating formula enriched with arginine, nucleotides, and w-3 fatty acids may be given to selective upper

43 Nutrition Support |

345 |

|

|

gastrointestinal surgical patients, but can be harmful to patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. As per current guidelines, patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome should receive enteral nutrition (EN) enriched with omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants.

Step 10: Look for tolerance to enteral feed

¥Signs of intolerance include bloating, nausea, cramps, abdominal distention, or diarrhea, but these signs are nonspeciÞc.

¥Intragastric feeds should not be stopped for residuals of less than 200 ml.

¥SigniÞcant distention or complaints of cramping by the patient should warrant slowing or discontinuing the feeds.

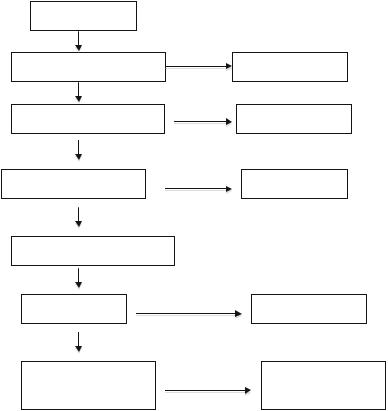

¥In case of diarrhea, follow a standard protocol (see Fig. 43.1).

Is diarrhea present? |

|

Yes |

|

|

No |

Is stool clinically significant? |

Continue same feeds |

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

Are medications responsible? |

Change medications |

No |

|

Is the patient on antibiotics? |

Yes |

Check for C.difficile. |

|

No |

|

Consider fiber or elemental diet |

|

Yes |

|

Diarrhea resolved |

Continue same feeds |

No |

|

Decrease feed rates till |

Advance to goal rate as |

tolerance is achieved |

tolerance improves |

Fig. 43.1 Resolving tube feeding-associated diarrhea

Step 11: Select candidates for parenteral nutrition

¥Parenteral nutrition is indicated for some critically ill patients in the following situations: