- •About the author

- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •This Book’s Approach

- •What’s New in the Seventh Edition?

- •The Arrangement of Topics

- •Part One, Introduction

- •Part Two, Classical Theory: The Economy in the Long Run

- •Part Three, Growth Theory: The Economy in the Very Long Run

- •Part Four, Business Cycle Theory: The Economy in the Short Run

- •Part Five, Macroeconomic Policy Debates

- •Part Six, More on the Microeconomics Behind Macroeconomics

- •Epilogue

- •Alternative Routes Through the Text

- •Learning Tools

- •Case Studies

- •FYI Boxes

- •Graphs

- •Mathematical Notes

- •Chapter Summaries

- •Key Concepts

- •Questions for Review

- •Problems and Applications

- •Chapter Appendices

- •Glossary

- •Translations

- •Acknowledgments

- •Supplements and Media

- •For Instructors

- •Instructor’s Resources

- •Solutions Manual

- •Test Bank

- •PowerPoint Slides

- •For Students

- •Student Guide and Workbook

- •Online Offerings

- •EconPortal, Available Spring 2010

- •eBook

- •WebCT

- •BlackBoard

- •Additional Offerings

- •i-clicker

- •The Wall Street Journal Edition

- •Financial Times Edition

- •Dismal Scientist

- •1-1: What Macroeconomists Study

- •1-2: How Economists Think

- •Theory as Model Building

- •The Use of Multiple Models

- •Prices: Flexible Versus Sticky

- •Microeconomic Thinking and Macroeconomic Models

- •1-3: How This Book Proceeds

- •Income, Expenditure, and the Circular Flow

- •Rules for Computing GDP

- •Real GDP Versus Nominal GDP

- •The GDP Deflator

- •Chain-Weighted Measures of Real GDP

- •The Components of Expenditure

- •Other Measures of Income

- •Seasonal Adjustment

- •The Price of a Basket of Goods

- •The CPI Versus the GDP Deflator

- •The Household Survey

- •The Establishment Survey

- •The Factors of Production

- •The Production Function

- •The Supply of Goods and Services

- •3-2: How Is National Income Distributed to the Factors of Production?

- •Factor Prices

- •The Decisions Facing the Competitive Firm

- •The Firm’s Demand for Factors

- •The Division of National Income

- •The Cobb–Douglas Production Function

- •Consumption

- •Investment

- •Government Purchases

- •Changes in Saving: The Effects of Fiscal Policy

- •Changes in Investment Demand

- •3-5: Conclusion

- •4-1: What Is Money?

- •The Functions of Money

- •The Types of Money

- •The Development of Fiat Money

- •How the Quantity of Money Is Controlled

- •How the Quantity of Money Is Measured

- •4-2: The Quantity Theory of Money

- •Transactions and the Quantity Equation

- •From Transactions to Income

- •The Assumption of Constant Velocity

- •Money, Prices, and Inflation

- •4-4: Inflation and Interest Rates

- •Two Interest Rates: Real and Nominal

- •The Fisher Effect

- •Two Real Interest Rates: Ex Ante and Ex Post

- •The Cost of Holding Money

- •Future Money and Current Prices

- •4-6: The Social Costs of Inflation

- •The Layman’s View and the Classical Response

- •The Costs of Expected Inflation

- •The Costs of Unexpected Inflation

- •One Benefit of Inflation

- •4-7: Hyperinflation

- •The Costs of Hyperinflation

- •The Causes of Hyperinflation

- •4-8: Conclusion: The Classical Dichotomy

- •The Role of Net Exports

- •International Capital Flows and the Trade Balance

- •International Flows of Goods and Capital: An Example

- •Capital Mobility and the World Interest Rate

- •Why Assume a Small Open Economy?

- •The Model

- •How Policies Influence the Trade Balance

- •Evaluating Economic Policy

- •Nominal and Real Exchange Rates

- •The Real Exchange Rate and the Trade Balance

- •The Determinants of the Real Exchange Rate

- •How Policies Influence the Real Exchange Rate

- •The Effects of Trade Policies

- •The Special Case of Purchasing-Power Parity

- •Net Capital Outflow

- •The Model

- •Policies in the Large Open Economy

- •Conclusion

- •Causes of Frictional Unemployment

- •Public Policy and Frictional Unemployment

- •Minimum-Wage Laws

- •Unions and Collective Bargaining

- •Efficiency Wages

- •The Duration of Unemployment

- •Trends in Unemployment

- •Transitions Into and Out of the Labor Force

- •6-5: Labor-Market Experience: Europe

- •The Rise in European Unemployment

- •Unemployment Variation Within Europe

- •The Rise of European Leisure

- •6-6: Conclusion

- •7-1: The Accumulation of Capital

- •The Supply and Demand for Goods

- •Growth in the Capital Stock and the Steady State

- •Approaching the Steady State: A Numerical Example

- •How Saving Affects Growth

- •7-2: The Golden Rule Level of Capital

- •Comparing Steady States

- •The Transition to the Golden Rule Steady State

- •7-3: Population Growth

- •The Steady State With Population Growth

- •The Effects of Population Growth

- •Alternative Perspectives on Population Growth

- •7-4: Conclusion

- •The Efficiency of Labor

- •The Steady State With Technological Progress

- •The Effects of Technological Progress

- •Balanced Growth

- •Convergence

- •Factor Accumulation Versus Production Efficiency

- •8-3: Policies to Promote Growth

- •Evaluating the Rate of Saving

- •Changing the Rate of Saving

- •Allocating the Economy’s Investment

- •Establishing the Right Institutions

- •Encouraging Technological Progress

- •The Basic Model

- •A Two-Sector Model

- •The Microeconomics of Research and Development

- •The Process of Creative Destruction

- •8-5: Conclusion

- •Increases in the Factors of Production

- •Technological Progress

- •The Sources of Growth in the United States

- •The Solow Residual in the Short Run

- •9-1: The Facts About the Business Cycle

- •GDP and Its Components

- •Unemployment and Okun’s Law

- •Leading Economic Indicators

- •9-2: Time Horizons in Macroeconomics

- •How the Short Run and Long Run Differ

- •9-3: Aggregate Demand

- •The Quantity Equation as Aggregate Demand

- •Why the Aggregate Demand Curve Slopes Downward

- •Shifts in the Aggregate Demand Curve

- •9-4: Aggregate Supply

- •The Long Run: The Vertical Aggregate Supply Curve

- •From the Short Run to the Long Run

- •9-5: Stabilization Policy

- •Shocks to Aggregate Demand

- •Shocks to Aggregate Supply

- •10-1: The Goods Market and the IS Curve

- •The Keynesian Cross

- •The Interest Rate, Investment, and the IS Curve

- •How Fiscal Policy Shifts the IS Curve

- •10-2: The Money Market and the LM Curve

- •The Theory of Liquidity Preference

- •Income, Money Demand, and the LM Curve

- •How Monetary Policy Shifts the LM Curve

- •Shocks in the IS–LM Model

- •From the IS–LM Model to the Aggregate Demand Curve

- •The IS–LM Model in the Short Run and Long Run

- •11-3: The Great Depression

- •The Spending Hypothesis: Shocks to the IS Curve

- •The Money Hypothesis: A Shock to the LM Curve

- •Could the Depression Happen Again?

- •11-4: Conclusion

- •12-1: The Mundell–Fleming Model

- •The Goods Market and the IS* Curve

- •The Money Market and the LM* Curve

- •Putting the Pieces Together

- •Fiscal Policy

- •Monetary Policy

- •Trade Policy

- •How a Fixed-Exchange-Rate System Works

- •Fiscal Policy

- •Monetary Policy

- •Trade Policy

- •Policy in the Mundell–Fleming Model: A Summary

- •12-4: Interest Rate Differentials

- •Country Risk and Exchange-Rate Expectations

- •Differentials in the Mundell–Fleming Model

- •Pros and Cons of Different Exchange-Rate Systems

- •The Impossible Trinity

- •12-6: From the Short Run to the Long Run: The Mundell–Fleming Model With a Changing Price Level

- •12-7: A Concluding Reminder

- •Fiscal Policy

- •Monetary Policy

- •A Rule of Thumb

- •The Sticky-Price Model

- •Implications

- •Adaptive Expectations and Inflation Inertia

- •Two Causes of Rising and Falling Inflation

- •Disinflation and the Sacrifice Ratio

- •13-3: Conclusion

- •14-1: Elements of the Model

- •Output: The Demand for Goods and Services

- •The Real Interest Rate: The Fisher Equation

- •Inflation: The Phillips Curve

- •Expected Inflation: Adaptive Expectations

- •The Nominal Interest Rate: The Monetary-Policy Rule

- •14-2: Solving the Model

- •The Long-Run Equilibrium

- •The Dynamic Aggregate Supply Curve

- •The Dynamic Aggregate Demand Curve

- •The Short-Run Equilibrium

- •14-3: Using the Model

- •Long-Run Growth

- •A Shock to Aggregate Supply

- •A Shock to Aggregate Demand

- •A Shift in Monetary Policy

- •The Taylor Principle

- •14-5: Conclusion: Toward DSGE Models

- •15-1: Should Policy Be Active or Passive?

- •Lags in the Implementation and Effects of Policies

- •The Difficult Job of Economic Forecasting

- •Ignorance, Expectations, and the Lucas Critique

- •The Historical Record

- •Distrust of Policymakers and the Political Process

- •The Time Inconsistency of Discretionary Policy

- •Rules for Monetary Policy

- •16-1: The Size of the Government Debt

- •16-2: Problems in Measurement

- •Measurement Problem 1: Inflation

- •Measurement Problem 2: Capital Assets

- •Measurement Problem 3: Uncounted Liabilities

- •Measurement Problem 4: The Business Cycle

- •Summing Up

- •The Basic Logic of Ricardian Equivalence

- •Consumers and Future Taxes

- •Making a Choice

- •16-5: Other Perspectives on Government Debt

- •Balanced Budgets Versus Optimal Fiscal Policy

- •Fiscal Effects on Monetary Policy

- •Debt and the Political Process

- •International Dimensions

- •16-6: Conclusion

- •Keynes’s Conjectures

- •The Early Empirical Successes

- •The Intertemporal Budget Constraint

- •Consumer Preferences

- •Optimization

- •How Changes in Income Affect Consumption

- •Constraints on Borrowing

- •The Hypothesis

- •Implications

- •The Hypothesis

- •Implications

- •The Hypothesis

- •Implications

- •17-7: Conclusion

- •18-1: Business Fixed Investment

- •The Rental Price of Capital

- •The Cost of Capital

- •The Determinants of Investment

- •Taxes and Investment

- •The Stock Market and Tobin’s q

- •Financing Constraints

- •Banking Crises and Credit Crunches

- •18-2: Residential Investment

- •The Stock Equilibrium and the Flow Supply

- •Changes in Housing Demand

- •18-3: Inventory Investment

- •Reasons for Holding Inventories

- •18-4: Conclusion

- •19-1: Money Supply

- •100-Percent-Reserve Banking

- •Fractional-Reserve Banking

- •A Model of the Money Supply

- •The Three Instruments of Monetary Policy

- •Bank Capital, Leverage, and Capital Requirements

- •19-2: Money Demand

- •Portfolio Theories of Money Demand

- •Transactions Theories of Money Demand

- •The Baumol–Tobin Model of Cash Management

- •19-3 Conclusion

- •Lesson 2: In the short run, aggregate demand influences the amount of goods and services that a country produces.

- •Question 1: How should policymakers try to promote growth in the economy’s natural level of output?

- •Question 2: Should policymakers try to stabilize the economy?

- •Question 3: How costly is inflation, and how costly is reducing inflation?

- •Question 4: How big a problem are government budget deficits?

- •Conclusion

- •Glossary

- •Index

526 | P A R T |

V I More on the Microeconomics Behind Macroeconomics |

|

|

|||||

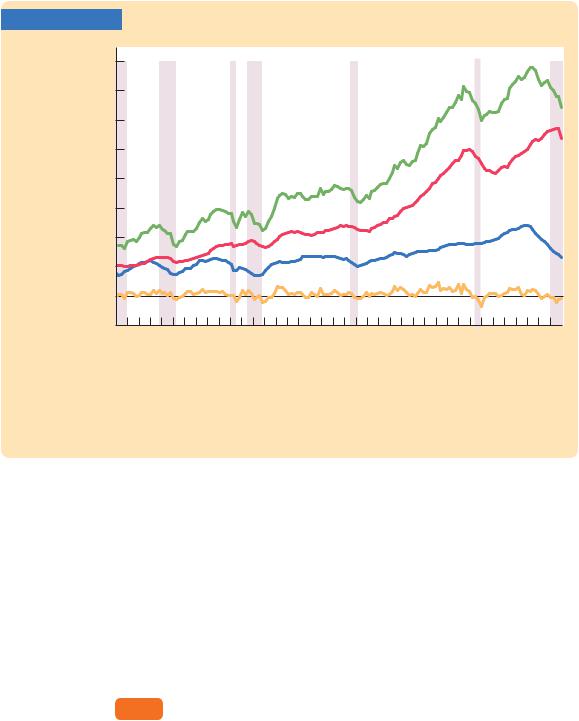

FIGURE 18-1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Billions of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2000 dollars 2000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1750 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1250 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1000 |

|

|

Total investment |

|

|

|

|

|

750 |

|

|

Business fixed investment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

500 |

|

|

Residential investment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

250 |

|

|

Change in inventories |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

250 |

1975 |

1980 |

1985 |

1990 |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

|

1970 |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year |

The Three Components of Investment This figure shows total investment, business fixed investment, residential investment, and inventory investment in the United States from 1970 to 2008. Notice that all types of investment usually fall during recessions, which are indicated here by the shaded areas.

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce and Global Financial Data.

In this chapter we build models of each type of investment to explain these fluctuations. The models will shed light on the following questions:

■Why is investment negatively related to the interest rate?

■What causes the investment function to shift?

■Why does investment rise during booms and fall during recessions?

At the end of the chapter, we return to these questions and summarize the answers that the models offer.

18-1 Business Fixed Investment

The largest piece of investment spending, accounting for about three-quarters of the total, is business fixed investment. The term “business” means that these investment goods are bought by firms for use in future production. The term “fixed” means that this spending is for capital that will stay put for a while, as

C H A P T E R 1 8 Investment | 527

opposed to inventory investment, which will be used or sold within a short time. Business fixed investment includes everything from office furniture to factories, computers to company cars.

The standard model of business fixed investment is called the neoclassical model of investment. The neoclassical model examines the benefits and costs to firms of owning capital goods. The model shows how the level of invest- ment—the addition to the stock of capital—is related to the marginal product of capital, the interest rate, and the tax rules affecting firms.

To develop the model, imagine that there are two kinds of firms in the economy. Production firms produce goods and services using capital that they rent. Rental firms make all the investments in the economy; they buy capital and rent it out to the production firms. Most firms in the real world perform both functions: they produce goods and services, and they invest in capital for future production. We can simplify our analysis and clarify our thinking, however, if we separate these two activities by imagining that they take place in different firms.

The Rental Price of Capital

Let’s first consider the typical production firm. As we discussed in Chapter 3, this firm decides how much capital to rent by comparing the cost and benefit of each unit of capital. The firm rents capital at a rental rate R and sells its output at a price P; the real cost of a unit of capital to the production firm is R/P. The real benefit of a unit of capital is the marginal product of capital MPK—the extra output produced with one more unit of capital. The marginal product of capital declines as the amount of capital rises: the more capital the firm has, the less an additional unit of capital will add to its output. Chapter 3 concluded that, to maximize profit, the firm rents capital until the marginal product of capital falls to equal the real rental price.

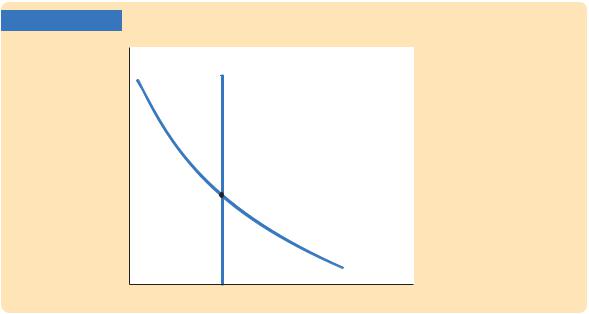

Figure 18-2 shows the equilibrium in the rental market for capital. For the reasons just discussed, the marginal product of capital determines the demand curve. The demand curve slopes downward because the marginal product of capital is low when the level of capital is high. At any point in time, the amount of capital in the economy is fixed, so the supply curve is vertical. The real rental price of capital adjusts to equilibrate supply and demand.

To see what variables influence the equilibrium rental price, let’s consider a particular production function. As we saw in Chapter 3, many economists consider the Cobb–Douglas production function a good approximation of how the actual economy turns capital and labor into goods and services. The Cobb–Douglas production function is

Y = AKaL1−a,

where Y is output, K is capital, L is labor, A is a parameter measuring the level of technology, and a is a parameter between zero and one that measures capital’s share of output. The marginal product of capital for the Cobb–Douglas production function is

MPK = aA(L/K )1−a.

528 | P A R T V I More on the Microeconomics Behind Macroeconomics

FIGURE 18-2

Real rental price, R/P

Capital supply

Capital demand (MPK)

K |

Capital stock, K |

The Rental Price of Capital The real rental price of capital adjusts to equilibrate the demand for capital (determined by the marginal product of capital) and the fixed supply.

Because the real rental price R/P equals the marginal product of capital in equilibrium, we can write

R/P = aA(L/K )1−a.

This expression identifies the variables that determine the real rental price. It shows the following:

■ The lower the stock of capital, the higher the real rental price of capital.

■The greater the amount of labor employed, the higher the real rental price of capital.

■The better the technology, the higher the real rental price of capital.

Events that reduce the capital stock (an earthquake), or raise employment (an expansion in aggregate demand), or improve the technology (a scientific discovery) raise the equilibrium real rental price of capital.

The Cost of Capital

Next consider the rental firms. These firms, like car-rental companies, merely buy capital goods and rent them out. Because our goal is to explain the investments made by the rental firms, we begin by considering the benefit and cost of owning capital.

The benefit of owning capital is the revenue earned by renting it to the production firms. The rental firm receives the real rental price of capital R/P for each unit of capital it owns and rents out.

C H A P T E R 1 8 Investment | 529

The cost of owning capital is more complex. For each period of time that it rents out a unit of capital, the rental firm bears three costs:

1.When a rental firm borrows to buy a unit of capital, it must pay interest on

the loan. If PK is the purchase price of a unit of capital and i is the nominal interest rate, then iPK is the interest cost. Notice that this interest cost would be the same even if the rental firm did not have to borrow: if the

rental firm buys a unit of capital using cash on hand, it loses out on the interest it could have earned by depositing this cash in the bank. In either case, the interest cost equals iPK.

2.While the rental firm is renting out the capital, the price of capital can change. If the price of capital falls, the firm loses, because the firm’s asset has

fallen in value. If the price of capital rises, the firm gains, because the firm’s

asset has risen in value. The cost of this loss or gain is −DPK. (The minus sign is here because we are measuring costs, not benefits.)

3.While the capital is rented out, it suffers wear and tear, called depreciation.

If d is the rate of depreciation—the fraction of capital’s value lost per period because of wear and tear—then the dollar cost of depreciation is dPK.

The total cost of renting out a unit of capital for one period is therefore

Cost of Capital = iPK − DPK + dPK

= PK(i − DPK/PK + d).

The cost of capital depends on the price of capital, the interest rate, the rate at which capital prices are changing, and the depreciation rate.

For example, consider the cost of capital to a car-rental company. The company buys cars for $10,000 each and rents them out to other businesses. The company faces an interest rate i of 10 percent per year, so the interest cost iPK is $1,000 per year for each car the company owns. Car prices are rising at 6 percent per year, so, excluding wear and tear, the firm gets a capital gain DPK of $600 per year. Cars depreciate at 20 percent per year, so the loss due to wear and tear dPK is $2,000 per year. Therefore, the company’s cost of capital is

Cost of Capital = $1,000 − $600 + $2,000

= $2,400.

The cost to the car-rental company of keeping a car in its capital stock is $2,400 per year.

To make the expression for the cost of capital simpler and easier to interpret, we assume that the price of capital goods rises with the prices of other goods. In this case, DPK/PK equals the overall rate of inflation p. Because i − p equals the real interest rate r, we can write the cost of capital as

Cost of Capital = PK(r + d).