- •Preface to the 3rd edition

- •General Pharmacology

- •Systems Pharmacology

- •Therapy of Selected Diseases

- •Subject Index

- •Abbreviations

- •General Pharmacology

- •History of Pharmacology

- •Drug and Active Principle

- •The Aims of Isolating Active Principles

- •European Plants as Sources of Effective Medicines

- •Drug Development

- •Congeneric Drugs and Name Diversity

- •Oral Dosage Forms

- •Drug Administration by Inhalation

- •Dermatological Agents

- •From Application to Distribution in the Body

- •Potential Targets of Drug Action

- •External Barriers of the Body

- •Blood–Tissue Barriers

- •Membrane Permeation

- •Binding to Plasma Proteins

- •The Liver as an Excretory Organ

- •Biotransformation of Drugs

- •Drug Metabolism by Cytochrome P450

- •The Kidney as an Excretory Organ

- •Presystemic Elimination

- •Drug Concentration in the Body as a Function of Time—First Order (Exponential) Rate Processes

- •Time Course of Drug Concentration in Plasma

- •Time Course of Drug Plasma Levels during Repeated Dosing (A)

- •Time Course of Drug Plasma Levels during Irregular Intake (B)

- •Accumulation: Dose, Dose Interval, and Plasma Level Fluctuation (A)

- •Dose–Response Relationship

- •Concentration–Effect Curves (B)

- •Concentration–Binding Curves

- •Types of Binding Forces

- •Agonists—Antagonists

- •Other Forms of Antagonism

- •Enantioselectivity of Drug Action

- •Receptor Types

- •Undesirable Drug Effects, Side Effects

- •Drug Allergy

- •Cutaneous Reactions

- •Drug Toxicity in Pregnancy and Lactation

- •Pharmacogenetics

- •Placebo (A)

- •Systems Pharmacology

- •Sympathetic Nervous System

- •Structure of the Sympathetic Nervous System

- •Adrenergic Synapse

- •Adrenoceptor Subtypes and Catecholamine Actions

- •Smooth Muscle Effects

- •Cardiostimulation

- •Metabolic Effects

- •Structure–Activity Relationships of Sympathomimetics

- •Indirect Sympathomimetics

- •Types of

- •Antiadrenergics

- •Parasympathetic Nervous System

- •Cholinergic Synapse

- •Parasympathomimetics

- •Parasympatholytics

- •Actions of Nicotine

- •Localization of Nicotinic ACh Receptors

- •Effects of Nicotine on Body Function

- •Aids for Smoking Cessation

- •Consequences of Tobacco Smoking

- •Dopamine

- •Histamine Effects and Their Pharmacological Properties

- •Serotonin

- •Vasodilators—Overview

- •Organic Nitrates

- •Calcium Antagonists

- •ACE Inhibitors

- •Drugs Used to Influence Smooth Muscle Organs

- •Cardiac Drugs

- •Cardiac Glycosides

- •Antiarrhythmic Drugs

- •Drugs for the Treatment of Anemias

- •Iron Compounds

- •Prophylaxis and Therapy of Thromboses

- •Possibilities for Interference (B)

- •Heparin (A)

- •Hirudin and Derivatives (B)

- •Fibrinolytics

- •Intra-arterial Thrombus Formation (A)

- •Formation, Activation, and Aggregation of Platelets (B)

- •Inhibitors of Platelet Aggregation (A)

- •Presystemic Effect of ASA

- •Plasma Volume Expanders

- •Lipid-lowering Agents

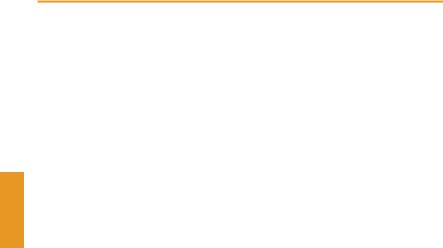

- •Diuretics—An Overview

- •NaCl Reabsorption in the Kidney (A)

- •Aquaporins (AQP)

- •Osmotic Diuretics (B)

- •Diuretics of the Sulfonamide Type

- •Potassium-sparing Diuretics (A)

- •Vasopressin and Derivatives (B)

- •Drugs for Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers

- •Laxatives

- •Antidiarrheal Agents

- •Drugs Affecting Motor Function

- •Muscle Relaxants

- •Nondepolarizing Muscle Relaxants

- •Depolarizing Muscle Relaxants

- •Antiparkinsonian Drugs

- •Antiepileptics

- •Pain Mechanisms and Pathways

- •Eicosanoids

- •Antipyretic Analgesics

- •Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

- •Cyclooxygenase (COX) Inhibitors

- •Local Anesthetics

- •Opioid Analgesics—Morphine Type

- •General Anesthesia and General Anesthetic Drugs

- •Inhalational Anesthetics

- •Injectable Anesthetics

- •Sedatives, Hypnotics

- •Benzodiazepines

- •Pharmacokinetics of Benzodiazepines

- •Therapy of Depressive Illness

- •Mania

- •Therapy of Schizophrenia

- •Psychotomimetics (Psychedelics, Hallucinogens)

- •Hypothalamic and Hypophyseal Hormones

- •Thyroid Hormone Therapy

- •Glucocorticoid Therapy

- •Follicular Growth and Ovulation, Estrogen and Progestin Production

- •Oral Contraceptives

- •Antiestrogen and Antiprogestin Active Principles

- •Aromatase Inhibitors

- •Insulin Formulations

- •Treatment of Insulin-dependent Diabetes Mellitus

- •Treatment of Maturity-Onset (Type II) Diabetes Mellitus

- •Oral Antidiabetics

- •Drugs for Maintaining Calcium Homeostasis

- •Drugs for Treating Bacterial Infections

- •Inhibitors of Cell Wall Synthesis

- •Inhibitors of Tetrahydrofolate Synthesis

- •Inhibitors of DNA Function

- •Inhibitors of Protein Synthesis

- •Drugs for Treating Mycobacterial Infections

- •Drugs Used in the Treatment of Fungal Infections

- •Chemotherapy of Viral Infections

- •Drugs for the Treatment of AIDS

- •Drugs for Treating Endoparasitic and Ectoparasitic Infestations

- •Antimalarials

- •Other Tropical Diseases

- •Chemotherapy of Malignant Tumors

- •Targeting of Antineoplastic Drug Action (A)

- •Mechanisms of Resistance to Cytostatics (B)

- •Inhibition of Immune Responses

- •Antidotes and Treatment of Poisonings

- •Therapy of Selected Diseases

- •Hypertension

- •Angina Pectoris

- •Antianginal Drugs

- •Acute Coronary Syndrome— Myocardial Infarction

- •Congestive Heart Failure

- •Hypotension

- •Gout

- •Obesity—Sequelae and Therapeutic Approaches

- •Osteoporosis

- •Rheumatoid Arthritis

- •Migraine

- •Common Cold

- •Atopy and Antiallergic Therapy

- •Bronchial Asthma

- •Emesis

- •Alcohol Abuse

- •Local Treatment of Glaucoma

- •Further Reading

- •Further Reading

- •Picture Credits

- •Drug Indexes

318 Therapy of Selected Diseases

Antianginal Drugs

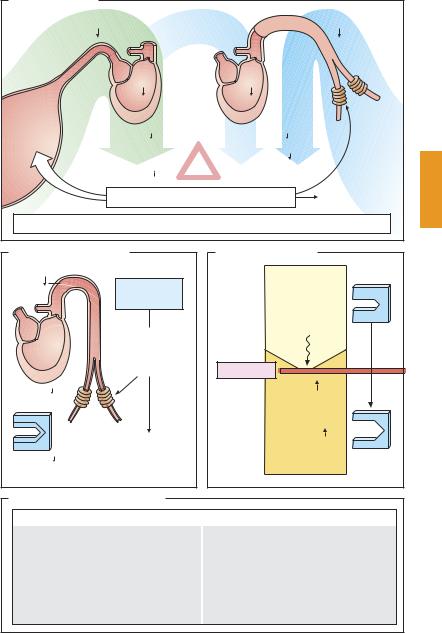

Antianginal agents derive from three drug groups, the pharmacological properties of which have already been presented in more detail: the organic nitrates (p.124), the calcium antagonists (p.126), and the β-blockers (p. 96).

Organic nitrates (A) increase blood flow, hence O2 supply, because diastolic wall tension (preload) declines as venous return to the heart is diminished. Thus, the nitrates enable myocardial flow resistance to be reduced even in the presence of coronary sclerosis with angina pectoris. In angina due to coronary spasm, arterial dilation overcomes the vasospasm and restores myocardial perfusion to normal. O2 demand falls because of the ensuing decrease in the two variables that determine systolic wall tension (afterload): ventricular filling volume and aortic blood pressure.

Calcium antagonists (B) decrease O2 demand by lowering aortic pressure, one of the components contributing to afterload. The dihydropyridine nifedipine, is devoid of a cardiodepressant effect, but may give rise to reflex tachycardia and an associated increase in O2 demand. The catamphiphilic drugs verapamil and diltiazem are cardiodepressant. Reduced beat frequency and contractility contribute to a reduction in O2 demand; however, AV-block and mechanical insuf ciency can dangerously jeopardize heart function. In coronary spasm, calcium antagonists can induce spasmolysis and improve blood flow.

β-Blockers (C) protect the heart against the O2-wasting effect of sympathetic drive by inhibiting β1-receptor-mediated increases in cardiac rate and speed of contraction.

Uses of antianginal drugs (D). For relief of the acute anginal attack, rapidly absorbed drugs devoid of cardiodepressant activity are preferred. The drug of choice is nitroglycerin (NTG, 0.8–2.4 mg sublingually; onset of ac-

tion within 1–2 minutes; duration of effect ~ 30 minutes). Isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) can also be used (5–10 mg sublingually); compared with NTG, its action is somewhat delayed in onset but of longer duration. Finally, nifedipine may be useful in chronic stable, or in variant angina (5–20 mg, capsule to be bitten and the content swallowed).

For sustained daytime angina prophylaxis, nitrates are of limited value because “nitrate pauses” of about 12 hours are appropriate if nitrate tolerance is to be avoided. If attacks occur during the day, ISDN, or its metabolite isosorbide mononitrate, may be given in the morning and at noon (e. g., ISDN 40 mg in extended-release capsules). Because of hepatic presystemic elimination, NTG is not suitable for oral administration. Continuous delivery via a transdermal patch would also not seem advisable because of the potential development of tolerance. With molsidomine, there is less risk of a nitrate tolerance; however, its clinical use is restricted owing to its potential carcinogenicity.

The choice between calcium antagonists must take into account the differential effect of nifedipine versus verapamil or diltiazem on cardiac performance (see above). When β-blockers are given, the potential consequences of reducing cardiac contractility (withdrawal of sympathetic drive) must be kept in mind. Since vasodilating β2-receptors are blocked, an increased risk of vasospasm cannot be ruled out. Therefore, monotherapy with β-blockers is recommended only in angina due to coronary sclerosis, but not in variant angina.

Antianginal Drugs |

319 |

A. Effects of nitrates

p |

Diastole |

Systole |

p |

|

Vol |

|

Vol |

|

|

|

Resistance |

Venous |

|

|

vessels |

|

|

|

|

capacitance |

Preload |

Nitrate |

Afterload |

vessels |

|

|

|

|

|

tolerance |

O2-demand |

|

|

|

|

|

O2-supply |

|

|

|

|

Vasorelaxation |

Relaxation of |

|

|

coronary spasm |

|

|

|

|

Nitrates, e.g., nitroglycerin (GTN), isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN)

B. Effects of Ca-antagonists |

C. Effects of β -blockers |

|

p |

|

Rest |

Ca- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

antagonists |

|

|

|

Sympathetic |

|

Relaxation |

system |

|

|

|

|

of |

|

|

resistance |

|

|

vessels |

β -Blocker |

|

|

|

Afterload |

|

Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

Contraction |

|

|

velocity |

|

Relaxation of |

|

O2-demand |

coronary spasm |

Exercise |

|

||

D. Clinical uses of antianginal drugs |

|

|

|

Angina pectoris |

|

Coronary sclerosis |

|

|

|

|

Coronary spasm |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Therapy of attack |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

GTN, |

ISDN |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nifedipine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anginal prophylaxis |

|

|

|||||

Long-acting nitrates |

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

β− Blockers |

|

|

Ca-antagonists |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

320 Therapy of Selected Diseases

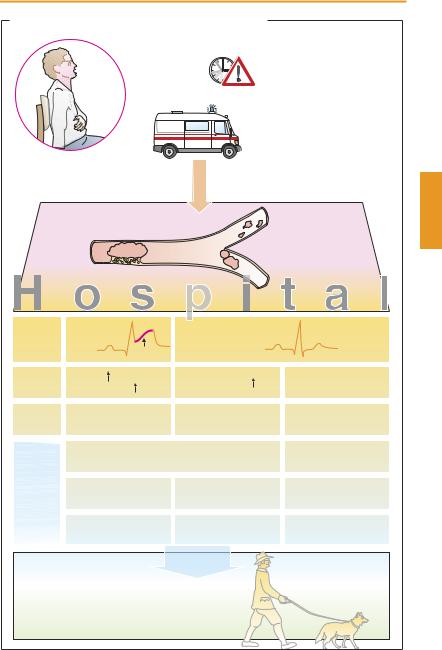

Acute Coronary Syndrome— Myocardial Infarction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is caused by the acute thrombotic occlusion of a coronary artery. The myocardial region that has been cut off from its blood supply dies within a short time owing to the lack of O2 and glucose. The loss in functional muscle tissue results in reduced cardiac performance. In the infarct border zone, spontaneous pacemaker potentials may develop, leading to fatal ventricular fibrillation. The patient experiences severe pain, a feeling of annihilation, and fear of dying.

MI usually develops after rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque within a coronary blood vessel. At this site, the clotting cascade is activated and the resultant thrombus occludes the lumen. In all patients under suspicion of MI, immediate therapy has to be initiated by the emergency physician. To relieve the patient from severe pain and anxiety, morphine and a benzodiazepine need to be given. Antiplatelet drugs and heparin are necessary for preventing further formation of thrombi. Nitroglycerin can be used to reduce cardiac load. When blood pressure and heart rate have stabilized, a β-blocker can be administered to lower cardiac O2 consumption and the risk of arrhythmias. Infusion of lidocaine is required to counter the threat of arrhythmias. The chance of survival of the MI patient depends on the interval between the onset of infarction and the start of therapy.

In the hospital, ECG and laboratory tests are performed promptly to determine the subsequent treatment strategy. When cardiomyocytes die, contractile proteins (troponin) or myocardial enzymes (creatine kinase, CK-MB) are liberated and can be detected in blood for diagnostic purposes. Marked elevation of the ST segment in the ECG raises the strong suspicion of a complete occlusion of a coronary artery (STelevation MI, STEMI). In these MI patients, reperfusion of the affected area as early and as completely as

possible may be life-saving. In this situation, removal of the coronary stenosis with a balloon catheter combined with implantation of a stent offers the best chance of survival but can be performed only in specialized cardiac centers. As dilatation of the vascular stenosis by the heart catheter liberates many thrombogenic mediators, platelet aggregation must be prevented by administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists (p.154).

If the MI patient cannot be transported to a cardiac center in time, fibrinolytic treatment of the coronary thrombus is instituted. For this purpose, fibrinolytics (streptokinase or recombinant tissue plasminogen activators) are given intravenously. Fibrinolysis is associated with an increased risk of bleeding; cerebral hemorrhages are of particular concern. A coronary bypass operation is available as a third therapeutic option.

Patients with persistent angina pectoris who lack an elevated ST segment in the ECG but show an elevated blood level of troponin may have a non-STEMI (“NSTEMI”). The most frequent cause is thrombi that have moved from the larger coronary arteries into smaller branches to produce a blockage there. If neither ST segment elevation nor biochemical MI markers can be ascertained, unstable angina pectoris is present, which is initially treated with antiplatelet drugs.

Post-MI management calls for strict adherence to a program of secondary prevention. Cardiac risk factors have to be excluded or modified, for instance, by reduction of overweight, cessation of smoking, optimal control of diabetes mellitus, and physical exercise (a dog that loves to run is an ideal training partner). Supportive pharmacotherapeutic measures include administration of platelet aggregation inhibitors, β-blockers, and ACE inhibitors.

|

|

|

|

Myocardial Infarction |

321 |

||

A. Myocardial infarction: pharmacotherapeutic approaches |

|

|

|||||

|

|

Acute symptoms: |

Acute care measures |

|

|||

|

|

severe pain |

|

– Nitroglycerin (reduction of |

|

||

|

|

sense of impending |

preand afterload) |

|

|||

|

|

doom |

|

– Acetylsalicylic acid |

|

||

|

Patient |

fear of dying |

|

(if needed i.v.) |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

(inhibition of platelet |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aggregation) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– Morphine (analgesia, sedation) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

– Oxygen via nasal tube |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hospitalization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

with minimal delay |

|

|

Acute coronary syndrome |

Plaque rupture |

|

|

|

|||

Angina pectoris > 20 min |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

Distal |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

thrombus |

|

|

|

Thrombus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ECG |

ST-elevation |

T |

No ST-elevation |

|

|

||

|

|

S |

|

|

|

|

|

Laboratory |

CK-MB |

|

|

Troponin-I, -T |

|

– |

|

|

Troponin-I, -T |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Diagnosis |

Myocardial infarction |

Myocardial infarction |

Unstable |

|

|||

|

(“STEMI”) |

|

|

(“NSTEMI”) |

|

angina pectoris |

|

Therapy |

General: O2, acetylsalicylic acid, |

|

Acetylsalicylic acid, |

|

|||

|

heparin, nitrates, β -blocker, morphine |

|

clopidrogel |

|

|||

|

PTCA (Stent) |

|

PTCA (Stent) |

|

Cardiac |

|

|

|

GPIIb/IIIa-Antagonist |

GPIIb/IIIa-Antagonist |

catheterization |

|

|||

|

or |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

fibrinolysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

or |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

bypass surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary prevention |

|

|

Discharge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

possibly: |

|

|

|

|

|

– Acetylsalicylic acid |

– Clopidrogel |

|

|

|

|

||

– β -Blocker |

– Phenprocoumon |

|

|

|

|||

– ACE inhibitor |

– Statins |

|

|

|

|

||