- •Preface to the 3rd edition

- •General Pharmacology

- •Systems Pharmacology

- •Therapy of Selected Diseases

- •Subject Index

- •Abbreviations

- •General Pharmacology

- •History of Pharmacology

- •Drug and Active Principle

- •The Aims of Isolating Active Principles

- •European Plants as Sources of Effective Medicines

- •Drug Development

- •Congeneric Drugs and Name Diversity

- •Oral Dosage Forms

- •Drug Administration by Inhalation

- •Dermatological Agents

- •From Application to Distribution in the Body

- •Potential Targets of Drug Action

- •External Barriers of the Body

- •Blood–Tissue Barriers

- •Membrane Permeation

- •Binding to Plasma Proteins

- •The Liver as an Excretory Organ

- •Biotransformation of Drugs

- •Drug Metabolism by Cytochrome P450

- •The Kidney as an Excretory Organ

- •Presystemic Elimination

- •Drug Concentration in the Body as a Function of Time—First Order (Exponential) Rate Processes

- •Time Course of Drug Concentration in Plasma

- •Time Course of Drug Plasma Levels during Repeated Dosing (A)

- •Time Course of Drug Plasma Levels during Irregular Intake (B)

- •Accumulation: Dose, Dose Interval, and Plasma Level Fluctuation (A)

- •Dose–Response Relationship

- •Concentration–Effect Curves (B)

- •Concentration–Binding Curves

- •Types of Binding Forces

- •Agonists—Antagonists

- •Other Forms of Antagonism

- •Enantioselectivity of Drug Action

- •Receptor Types

- •Undesirable Drug Effects, Side Effects

- •Drug Allergy

- •Cutaneous Reactions

- •Drug Toxicity in Pregnancy and Lactation

- •Pharmacogenetics

- •Placebo (A)

- •Systems Pharmacology

- •Sympathetic Nervous System

- •Structure of the Sympathetic Nervous System

- •Adrenergic Synapse

- •Adrenoceptor Subtypes and Catecholamine Actions

- •Smooth Muscle Effects

- •Cardiostimulation

- •Metabolic Effects

- •Structure–Activity Relationships of Sympathomimetics

- •Indirect Sympathomimetics

- •Types of

- •Antiadrenergics

- •Parasympathetic Nervous System

- •Cholinergic Synapse

- •Parasympathomimetics

- •Parasympatholytics

- •Actions of Nicotine

- •Localization of Nicotinic ACh Receptors

- •Effects of Nicotine on Body Function

- •Aids for Smoking Cessation

- •Consequences of Tobacco Smoking

- •Dopamine

- •Histamine Effects and Their Pharmacological Properties

- •Serotonin

- •Vasodilators—Overview

- •Organic Nitrates

- •Calcium Antagonists

- •ACE Inhibitors

- •Drugs Used to Influence Smooth Muscle Organs

- •Cardiac Drugs

- •Cardiac Glycosides

- •Antiarrhythmic Drugs

- •Drugs for the Treatment of Anemias

- •Iron Compounds

- •Prophylaxis and Therapy of Thromboses

- •Possibilities for Interference (B)

- •Heparin (A)

- •Hirudin and Derivatives (B)

- •Fibrinolytics

- •Intra-arterial Thrombus Formation (A)

- •Formation, Activation, and Aggregation of Platelets (B)

- •Inhibitors of Platelet Aggregation (A)

- •Presystemic Effect of ASA

- •Plasma Volume Expanders

- •Lipid-lowering Agents

- •Diuretics—An Overview

- •NaCl Reabsorption in the Kidney (A)

- •Aquaporins (AQP)

- •Osmotic Diuretics (B)

- •Diuretics of the Sulfonamide Type

- •Potassium-sparing Diuretics (A)

- •Vasopressin and Derivatives (B)

- •Drugs for Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers

- •Laxatives

- •Antidiarrheal Agents

- •Drugs Affecting Motor Function

- •Muscle Relaxants

- •Nondepolarizing Muscle Relaxants

- •Depolarizing Muscle Relaxants

- •Antiparkinsonian Drugs

- •Antiepileptics

- •Pain Mechanisms and Pathways

- •Eicosanoids

- •Antipyretic Analgesics

- •Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

- •Cyclooxygenase (COX) Inhibitors

- •Local Anesthetics

- •Opioid Analgesics—Morphine Type

- •General Anesthesia and General Anesthetic Drugs

- •Inhalational Anesthetics

- •Injectable Anesthetics

- •Sedatives, Hypnotics

- •Benzodiazepines

- •Pharmacokinetics of Benzodiazepines

- •Therapy of Depressive Illness

- •Mania

- •Therapy of Schizophrenia

- •Psychotomimetics (Psychedelics, Hallucinogens)

- •Hypothalamic and Hypophyseal Hormones

- •Thyroid Hormone Therapy

- •Glucocorticoid Therapy

- •Follicular Growth and Ovulation, Estrogen and Progestin Production

- •Oral Contraceptives

- •Antiestrogen and Antiprogestin Active Principles

- •Aromatase Inhibitors

- •Insulin Formulations

- •Treatment of Insulin-dependent Diabetes Mellitus

- •Treatment of Maturity-Onset (Type II) Diabetes Mellitus

- •Oral Antidiabetics

- •Drugs for Maintaining Calcium Homeostasis

- •Drugs for Treating Bacterial Infections

- •Inhibitors of Cell Wall Synthesis

- •Inhibitors of Tetrahydrofolate Synthesis

- •Inhibitors of DNA Function

- •Inhibitors of Protein Synthesis

- •Drugs for Treating Mycobacterial Infections

- •Drugs Used in the Treatment of Fungal Infections

- •Chemotherapy of Viral Infections

- •Drugs for the Treatment of AIDS

- •Drugs for Treating Endoparasitic and Ectoparasitic Infestations

- •Antimalarials

- •Other Tropical Diseases

- •Chemotherapy of Malignant Tumors

- •Targeting of Antineoplastic Drug Action (A)

- •Mechanisms of Resistance to Cytostatics (B)

- •Inhibition of Immune Responses

- •Antidotes and Treatment of Poisonings

- •Therapy of Selected Diseases

- •Hypertension

- •Angina Pectoris

- •Antianginal Drugs

- •Acute Coronary Syndrome— Myocardial Infarction

- •Congestive Heart Failure

- •Hypotension

- •Gout

- •Obesity—Sequelae and Therapeutic Approaches

- •Osteoporosis

- •Rheumatoid Arthritis

- •Migraine

- •Common Cold

- •Atopy and Antiallergic Therapy

- •Bronchial Asthma

- •Emesis

- •Alcohol Abuse

- •Local Treatment of Glaucoma

- •Further Reading

- •Further Reading

- •Picture Credits

- •Drug Indexes

Therapy of Selected Diseases

Hypertension |

314 |

|

|

||

Angina Pectoris |

316 |

|

|

||

Antianginal Drugs |

318 |

|

|||

Myocardial Infarction |

320 |

|

|||

Congestive Heart Failure 322 |

|

||||

Hypotension |

324 |

|

|

||

Gout 326 |

|

|

|

|

|

Obesity |

328 |

|

|

|

|

Osteoporosis |

330 |

|

|

||

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

332 |

|

|||

Migraine |

334 |

|

|

|

|

Common Cold |

336 |

|

|

||

Atopy and Antiallergic Therapy |

338 |

||||

Bronchial Asthma |

340 |

|

|||

Emesis |

342 |

|

|

|

|

Alcohol Abuse |

344 |

|

|

||

Local Treatment of Glaucoma |

346 |

||||

314 Therapy of Selected Diseases

Hypertension

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death in the Western world. Basically, atherosclerosis manifests itself in three major organs and thereby leads to severe secondary diseases. Coronary disease results from atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries and culminates in myocardial infarction when vessels are occluded by a thrombus. In the brain, atherosclerosis gives rise to arterial thrombi or ruptures that result in a stroke. Atherosclerosis in the kidney leads to renal failure. Since these diseases significantly lower life expectancy, early recognition and elimination of risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and smoking) that promote atherosclerosis are essential.

Hypertension is considered to be present when systolic blood pressure exceeds 140 mmHg and the diastolic value lies above 90 mmHg. Since cardiovascular risk increases over a wide range with increasing blood pressure, no “threshold value” exists that defines hypertension unequivocally. If other risk factors are present, blood pressure should be brought down to an even lower level (in diabetes mellitus below 130/80 mmHg). Therapeutic objectives comprise the prevention of organ damage and reduction of mortality. Because these target parameterscannot bemeasured in individual patients, the “surrogate parameter” of lowering of blood pressure is defined as the immediate goal. Before drug therapy is instituted, the patient has to be instructed to lower body weight (BMI < 30), to reduce consumption of alcohol (in men < 20–30 g ethanol/day; in women 10–20 g/day), to stop smoking, and to restrict the daily intake of NaCl (to 6 g/day).

The drugs of first choice in antihypertensive therapy are those that have been unambiguously shown in clinical studies to reduce mortality of hypertension—diuretics, ACE inhibitors and AT1 antagonist, β-blockers, and calcium antagonists.

Among the diuretics, thiazides are particularly recommended for treatment of hypertension. To avoid undue loss of K+, combination with triamterene or amiloride is often advantageous.

ACE inhibitors prevent the formation of angiotensin II by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and thereby reduce peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure. In addition, ACE inhibitors prevent the effect of angiotensin II on protein synthesis in myocardial and vascular muscle cells, and thus diminish ventricular hypertrophy. As adverse effects, ACE inhibitors may provoke dry cough, impaired renal function, and hyperkalemia. When ACE inhibitors are poorly tolerated, an AT1-receptor antagonist can be given.

From the group of antagonists at β-adre- noceptors, β1-selective blockers are mainly used (e. g., metoprolol). Owing to blockade of β2-receptors, β-blockers can impair pulmonary function, particularly in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease.

Among calcium antagonists, dihydropyridines with long half-lives are advantageous because short-acting drugs, which rapidly lower blood pressure, are prone to elicit reflex tachycardia.

Fewer that 50% of hypertensive patients are adequately managed by monotherapy. If the monotherapy fails, either the drug should be discontinued or two agents should be combined in reduced dosage (thiazide and β-blocker, or/and ACE inhibitor, or/and calcium-antagonist). Combinations that abolish the counterregulation against the primary antihypertensive drug are especially effective. For instance, diuretic-induced loss of Na+ and water leads to a compensatory activation of the renin–angiotensin system that can be eliminated by ACE inhibitors or AT1-antagonists.

Hypertension 315

A. Risk factors of atherosclerosis and secondary diseases

R i s k f a c t o r s

Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking

Brain |

Heart |

|

Athero- |

|

|

sclerosis |

|

|

Kidney |

Coronary |

|

|

||

Renal |

heart disease |

|

Myocardial |

||

failure |

||

Stroke: |

infarction |

|

Infarction |

Congestive |

|

Hemorrhage |

||

heart failure |

||

|

||

Diminished life expectancy |

|

B. Therapy of hypertension

H y p e r t e n s i o n > 1 4 0 / 9 0 m m H g

Healthy diet (low NaCl), weight reduction, no smoking, alcohol restriction, exercise

Thiazide diuretics |

If antihypertensive effect insufficient, add:

β -Blocker or ACE inhibitor, |

angiotensin receptor antagonist or calcium antagonist |

If still not sufficient:

Combination therapy:

+ clonidine or α 1-antagonists or vasodilators

Therapeutic aim:

Lowering of blood pressure

(< 140/90, in diabetes < 130/80 mmHg); and, hence, reduction in cardiovascular mortality

316 Therapy of Selected Diseases

Angina Pectoris

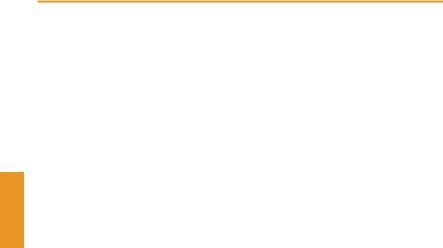

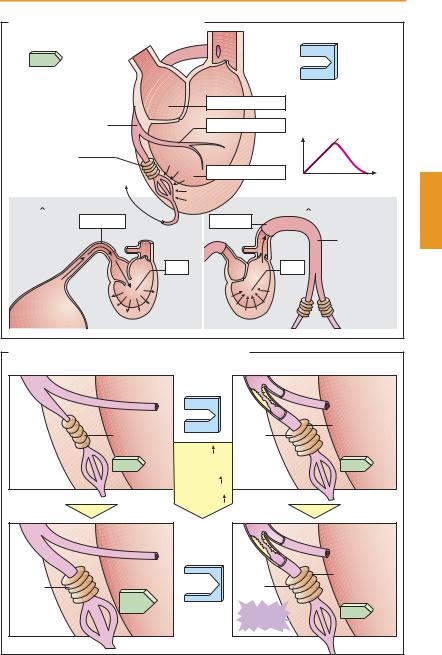

An anginal pain attack signals a transient hypoxia of the myocardium. As a rule, the oxygen deficit results from inadequate myocardial blood flow due to narrowing of larger coronary arteries. The underlying causes are most commonly an atherosclerotic change of the vascular wall (coronary sclerosis with exertional angina); very infrequently a spasmodic constriction of a morphologically healthy coronary artery (coronary spasm with angina at rest; variant angina); or more often a coronary spasm occurring in an atherosclerotic vascular segment.

The goal of treatment is to prevent myocardial hypoxia either by raising blood flow (oxygen [O2] supply) or by lowering myocardial oxygen demand (O2 demand) (A).

Factors determining oxygen supply. The force driving myocardial blood flow is the pressure difference between the coronary ostia (aortic pressure) and the opening of the coronary sinus (right atrial pressure). Blood flow is opposed by coronary flow resistance, which includes three components:

1.Owing to their large caliber, the proximal coronary segments do not normally contribute significantly to flow resistance. However, in coronary sclerosis or spasm, pathological obstruction of flow occurs here. Whereas the more common coronary sclerosis cannot be overcome pharmacologically, the less common coronary spasm can be relieved by appropriate vasodilators (nitrates, nifedipine).

2.The caliber of arteriolar resistance vessels controls blood flow through the coronary bed. Arteriolar caliber is determined by myocardial O2 tension and local concentrations of metabolic products, and is “automatically” adjusted to the required blood flow (B, healthy subject). This metabolic autoregulation explains why anginal attacks in coronary sclerosis occur only during exercise (B, patient). At rest, the pathologically elevated flow resistance is

compensated by a corresponding decrease in arteriolar resistance, ensuring adequate myocardial perfusion. During exercise, further dilation of arterioles is impossible. As a result, there is ischemia associated with pain. Pharmacological agents that act to dilate arterioles would thus be inappropriate because at rest they may divert blood from underperfused into healthy vascular regions on account of redundant arteriolar dilation. The resulting “steal effect” could provoke an anginal attack.

3.The intramyocardial pressure, i. e., systolic squeeze, compresses the capillary bed. Myocardial blood flow is halted during systole and occurs almost entirely during diastole. Diastolic wall tension (“preload”) depends on ventricular volume and filling pressure. The organic nitrates reduce preload by decreasing venous return to the heart.

Factors determining oxygen demand. The heart muscle cell consumes the most energy to generate contractile force. O2 demand rises with an increase in (1) heart rate, (2) contraction velocity, (3) systolic wall tension

(“afterload”). The last depends on ventricular volume and the systolic pressure needed to empty the ventricle. As peripheral resistance increases, aortic pressure rises and, hence, the resistance against which ventricular blood is ejected. O2 demand is lowered by β-blockers and calcium-antagonists, as well as by nitrates (p. 318).

|

Angina Pectoris |

|

317 |

|

A. O2 supply and demand of the myocardium |

|

|

|

|

O2-supply |

|

O |

2 |

-demand |

during |

|

|

|

|

|

during |

|||

diastole |

|

|||

|

systole |

|||

|

|

|||

Flow resistance: |

Left atrium |

1. Heart rate |

|

|

1. Coronary arterial |

Coronary artery |

2. Contraction |

||

caliber |

|

velocity |

|

|

2. Arteriolar |

|

p-force |

|

|

caliber |

Left ventricle |

|

|

|

Right |

|

|

Time |

|

atrium |

|

|

|

|

3. Diastolic |

|

3. Systolic wall |

|

|

wall tension |

|

tension |

|

|

= Preload |

|

= Afterload |

|

|

Pressure p |

Pressure p |

|

|

|

Venous |

|

Aorta |

||

|

|

|

|

|

supply |

|

|

|

|

Vol. |

|

Vol. |

|

|

|

|

Peripheral |

||

|

|

resistance |

||

Venous |

|

|

|

|

reservoir |

|

|

|

|

B. Pathogenesis of exertion angina in coronary sclerosis |

|

|

|

|

Healthy subject |

Patient with coronary sclerosis |

|||

|

Rest |

Compensa- |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

tory |

|

|

|

|

dilatation of |

||

Narrow |

Wide |

arterioles |

||

|

|

|

||

|

Rate |

|

|

|

Contraction |

|

|

|

|

|

velocity |

|

|

|

Afterload |

|

|

|

|

|

Exercise |

|

|

|

|

|

Additional |

||

|

|

dilatation |

||

|

|

not possible |

||

Wide |

Wide |

|

|

|

|

Angina |

|

|

|

|

pectoris |

|

|

|