Ghai Essential Pediatrics8th

.pdf

skin test. Components of vaccinesimplicated in mediating allergic reactions include (i)Egg protein: yellow fever (skin test mandatory; may also contain chicken protein), measles, MMR, rabies PCEV, influenza killed injectable and live attenuated vaccines; (ii) gelatin: influenza, measles, MMR, rabies, varicella, yellow fever and zoster vaccines; (iii) latex in the rubber of the vaccine vialstopper or syringe plunger; (iv) casein: DTaP vaccine; and

(v) Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast: hepatitis B and human papillomavirus vaccines. Antimicrobials added to vaccines in traces (e.g. neomycin) rarely cause allergic reactions. Thimerosal, aluminum and phenoxyethanol, added to some vaccines as preservatives, may cause delayed type hypersensitivity or contact dermatitis. The use of thimerosal has declined due to concerns over mercury exposure. Rare delayed reactions are erythema nodosum and encephalopathy.

Reportable events following vaccination include:

(i) anaphylaxis or anaphylactic shock s7 days of any vaccine; (ii) adverse effects listed as contraindications to future vaccinationinthepackageinsert; (iii)anyseriousor unusual event;and (iv)anysequelae of reportable events. Vaccine-specific reportable events include: (i) oral polio: paralytic polio or vaccine-strain polio within 1-6 months of vaccine administration; (ii) measles: thrombocytopenic purpura within 7-30 days; measles infection by vaccine strain in an immunodeficient recipient s6 months of vaccination; (iii) measles, mumps and/ or rubella: encephalopathy or encephalitis <15 days; (iv) tetanus: brachialneuritiss28days;(v)pertussis: encephalopathyor encephalitis s7 days; (vi) rotavirus: intussusception s30 days; and (vii) rubella: chronic arthritis <6 weeks.

Vaccine Storage and Cold Chain

The cold chain is a system of storing and transporting vaccines at recommended temperatures from the point of manufacture to the point of use. Maintenance of appro priate temperature is critical to the viability and potency of a vaccine. Vaccines such as BCG (especially after reconstitution), OPVand measles are sensitive toheat but can be frozen without harm. In contrast, vaccines like OT, DPT, dT, hepatitis B and tetanus toxoid are less sensitive to heat and are damaged by freezing. Other vaccines that must not be frozen include hepatitis A, Hib and whole cell killed typhoid vaccine. In the refrigerator, OPV vials are stored in the freezer compartment (0 to -4°C). In the main compartment (4-10°C) BCG, measles and MMR are kept in the top rack (below the freezer); other vaccines like DPT, OT, TT, hepatitis A and typhoid are stored in the middle racks; while hepatitis B, varicella and diluents are stored in the lower racks.

IMMUNIZATION PROGRAMS

The ExpandedProgram ofImmunization (EPI), introducedby theWorldHealthOrganization(WHO)in1974,wasthefirst globalinitiativeatimmunizationandfocusedonvaccinating

Immunization and Immunodeficiency -

young children and pregnant women. When adopted by India in 1978, the EPI includedBacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG), diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and whole cell pertussis (DTwP), oral poliomyelitis (OPV) and typhoid vaccines, and covered chiefly urban areas. The Universal Immunization Program (UIP) was introduced in 1985 to improveimmunizationcoveragewithinIndiaandtoextend itsfocusbeyond infancy. Measles vaccinewasaddedtothe Program and typhoid vaccine excluded. Further, vitamin A supplementation was introduced in 1990 and Polio NationalImmunization Days wereinitiatedin1995.Under theUIP,somestateshaveinitiateduniversalimmunization against hepatitis Bvirus since 2002. A pentavalent vaccine combining Haemophilus influenza b (Hib) and hepatitis B vaccines with diphtheria toxoid, whole cell pertussis and tetanustoxoid(DTwP)vaccineshasbeenintroducedinsome states since 2011. The UlP has remained an essential part oftheChildSurvivalandSafeMotherhood(CSSM)program in1992,theReproductiveandChildHealth(RCH)program I in1997andthe RCHIIand National RuralHealthMission (NRHM) since 2005. The efforts of UIP are also supported by Child Vaccine Initiative (CVI) and Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI).

The proportion of 1-yr-old children immunized against measles is an important indicator for immunization coverage within the country. While the UIP achieved a significant decline in the incidence of vaccine preventable diseases,thefindingsoftheNationalFamilyHealthSurvey 2005-2006 suggested that only 43.5% of children in India received all theprimaryvaccines by 12 months of age and this coverage was below 30% in Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan andArunachalPradesh.TheImmunizationStrengthening Project of the Government of India was launched with the intent to: (i) strengthen routine immunization rates to increase the percentage of fully immunized children to above 80%; (ii) eliminate and eradicate polio; (iii) review and develop a new immunization program based on the availability of newer vaccines, recent advances in vaccine production and cold chain technologies and the changing epidemiology of diseases; and (iv) improve vaccination surveillance and monitoring. This program is being implementedthroughtheNational InstituteofHealthand Family Welfare and regional training centers.

Strengthening of immunizationcoverageis an important component of the NRHM. Measures proposed to improve vaccination rates include mobilization of children and pregnant women by Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) and link workers to increase coverage and decrease dropouts, provisionof auto-disable syringes and other disposable and strengthening of cold chain maintenance and immunization monitoring systems.

Recommendations of the Indian Academy of

Pediatrics Committee on Immunization (IAPCOI)

The IAPCOI endorses the National Immunization Program, but recommends certain additional vaccines for

|

E |

s s en t ia P ed iat rics |

____________ |

_____________________ _ |

|

___ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ |

|

|

|

|

Indian view of data available on vaccine preventable dis eases (VPDs) and the availability of severalvaccines.These include the vaccines for hepatitis A, Haemophilusinfluenzae type b, MMR, typhoid, pneumococcal, varicella, HPV, and rotavirus vaccine. The differences in the National Immuni zation Program and the recommendations of the IAP are highlighted in Table 9.7.

IMMUNIZATION IN SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

The Indian Academy of Pediatrics also categorizes certain high-risk categories of children that need to be adminis-

teredadditionalvaccines (Table9.8). Some specific aspects are discussed here.

Lapsed immunization. Table 9.9 outlines suggested schedules for children who have missed routine immunization. The vaccination schedule for adolescents is discussed in Chapter 4.

Preterm neonates. Most preterm andlow birthweight babies mount adequate immune responses, and should receive immunization at the same chronological age and according to the same scheduleandprecautionsasforfull term infants. The dose administered is as for other infants,

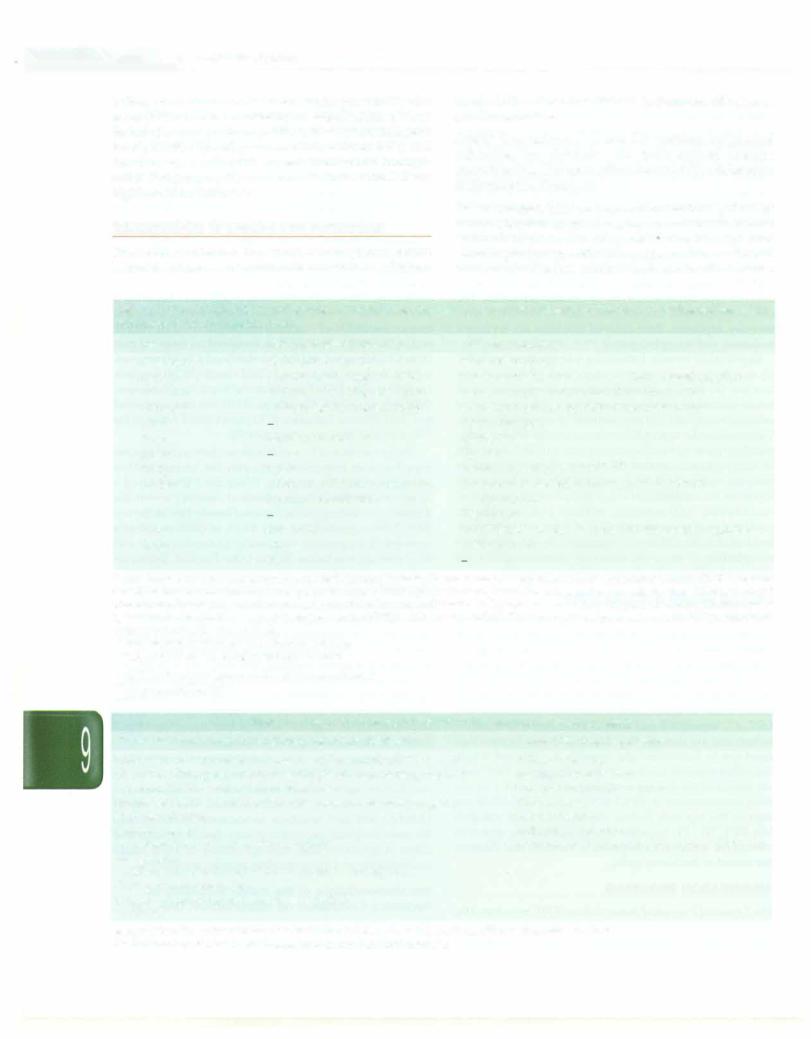

Table 9.7: Comparison of the vaccinations scheduled in the National Immunization Program and the 2012 recommendations of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP)

Age |

National Immunization Program |

IAP recommendation |

0 (at birth) |

BCG,OPVO,HepBO* |

BCG,OPVO,HepBl |

6 weeks |

DTwPl,OPVl,HepBl*,Hibl* |

DTwPl/DTaPl,IPV1$,HepB2,Hibl,Rotavirusl,PCVl |

10 weeks |

DTwP2,OPV2,HepB2*,Hib2* |

DTwP2/DTaP2,IPV2$,Hib2,Rotavirus2,PCV2 |

14 weeks |

DTwP3,OPV3,HepB3*,Hib3* |

DTwP3/DTaP3,IPV3$,Hib3, Rotavirus3, PCV3 |

6 mo |

|

OPVl/HepB3 |

9 mo |

Measles,vitamin Al |

OPV2,Measles |

12 mo |

|

Hep Al |

15 mo |

MMR* |

MMRl,Varicellal,PCVBl |

16-24 mo |

DTwPBl,OPVBl,vitamin A26, |

(16-18 mo) DTwPBl/DTaPBl,IPVBl$,HibBl |

|

Japanese encephalitis*• |

(18 mo) Hep A2 |

2 yr |

|

Typhoidl** |

5 yr |

DTwPB2 |

DTwPB2/DTaPB2,OPV3,MMR2,Varicella2,Typhoid2 |

10 yr |

TT |

TdaP/ Td$$,HPV |

16 yr |

TT |

|

Bl first booster dose; B2 second booster dose; BCG Bacillus Calrnette Guerin vaccine; OT diphtheria toxoid with tetanus toxoid; DTwP diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, whole cell killed pertussis vaccine; DTaP diphtheria toxoid,tetanus toxoid, acellular pertussis vaccine; Td tetanus toxoid with reduced dose diphtheria; Tdap tetanustoxoid withreduced dose diphtheria and pertussis vaccine; Hep B hepatitis B vaccine; HibHaemophilus influenzae bvaccine;HPVhuman papillomavirus vaccine; MMRmeasles,mumps andrubellavaccine;OPV oral poliovirusvaccine; PCVpneumococcal conjugate vaccine; TT tetanus toxoid

*lrnplemented in selected states, districts and cities

••SA 14-14-2 vaccine, in select endemic districts

s OPV if a inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) is not afforded ss dT preferred over TT

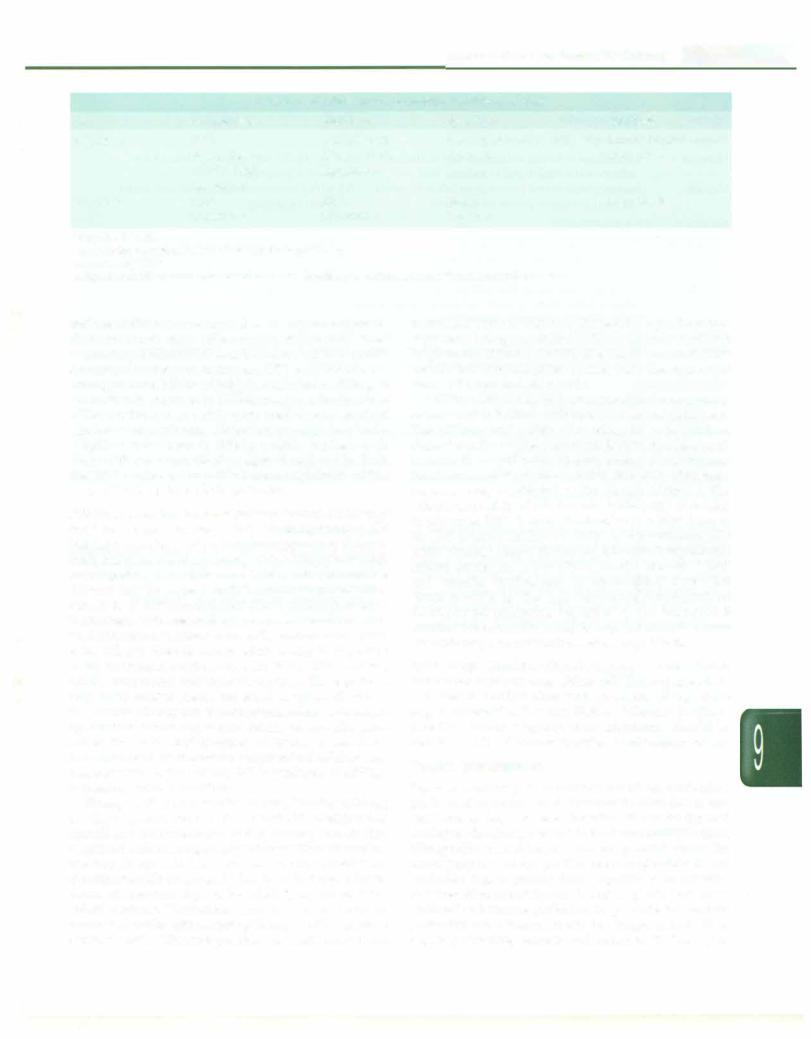

Table 9.8: High-risk conditions in which certain vaccines may be necessary

Circumstances that increase risk of acquiring certain infections |

Vaccines that may be necesssary |

Congenital or acquired immunodeficiency (including HIV infection) |

Influenza vaccine |

Chronic cardiac,pulmonary•,hematologic,renal (including nephrotic |

Meningococcal vaccine |

syndrome),liver disease and diabetes mellitus |

Japanese encephalitis vaccine |

Prolonged therapy with steroids,other irnrnunosuppressive agents |

Cholera vaccine |

Radiation therapy |

Rabies vaccine |

Diabetes mellitus |

Yellow fever vaccine |

Cerebrospinal fluid leak,cochlear implant |

Pneurnococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV 23) |

Malignancies |

|

Children with functional/anatomic asplenia/hyposplenia |

|

During disease outbreaks |

|

Laboratory personnel and health care workers |

|

Travelers |

|

Adapted from the recommendations of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Immunization, 2012 *includes asthma if treated with prolonged high-dose oral corticosteroids

Immunization and Immunodeficiency -

|

Table 9.9: Vaccination of a previously unimmunized child |

|

||

Visit |

At evaluation |

After 1 mo |

After 2 mo |

After 6 mo |

Age 7 yr |

BCG1 |

Oral polio virus1 |

MMR (preferred) or measles |

DTwP/DTaP |

|

Oral poliovirus1 |

DTwP/DTaP |

Typhoid |

Hepatitis B |

|

DTwP/DTaP |

Hepatitis B |

|

|

|

Hepatitis B |

|

|

|

Age >7 yr |

Tdap |

dT3 |

MMR |

Hepatitis B |

|

Hepatitis B |

Hepatitis B |

Typhoid |

|

1 If age is <5-yr-old

2Repeat after ?.4 weeks if not received any doses previously 3Repeat every 10 yr

Adapted from the recommendations of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Immunization, 2012

and use of divided orreduced doses is not recommended. Seroconversion rates following most live and killed vaccinesaresimilartofulltermbabies, exceptfor hepatitis B vaccine.Seroconversion rates are HBV vaccine are lower among preterm babies with birthweight below 2000 g. If the mother is known to be HBsAg negative, the first dose of the vaccine can be safely postponed to one month of age for such newborns. However, preterm low birth weight neonates born to HBsAg positive mothers or to those with unknown HBsAg status should receive both the HBV vaccine and hepatitis B immunoglobulin within 12 hr of birth for immediate protection.

Primary or secondary immunodeficiency Immunodeficiency may be primary or secondary to malignancy, HIV infection, steroids or other immunosuppressive therapy. Such children are at increased risk of infections with certain pathogens, andthe severity of vaccine preventable diseases may be higher than in immunocompetent child ren. It is recommended that these children receive inactivated influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. Live viral orbacterialvaccines are usually contraindicated due to the risk of serious disseminated disease bythe organism in the attenuated vaccine, e.g. with BCG, OPV, measles, MMR, oral typhoid and varicella vaccines. These patients may safely receive toxoid and killed vaccines. However, the vaccine efficacy may be compromised due to immune dysfunction, which mayrequire testingfor specific serum antibodies, and administration of further doses. Since householdcontacts of immunocompromisedchildren may transmit OPV to the patient, IPV is preferred in siblings of immunodeficient children.

Therapy with corticosteroids at 2 mg/kg/day or20 mg per day of prednisolone or its equivalent is considered as significant immunosuppression during which live vaccines should notbegiven; killedorinactivated vaccines and toxoids are safe. Live vaccines may be administered if corticosteroids are given for less than 14 days, in lower doses, on alternate days or by inhaled, topical or intra articular routes. Vaccination with live vaccines may be resumed 4 weeks after stopping therapy with high dose corticosteroids. Wherever possible, vaccinationshould be

completed prior to initiation of chemotherapy, immuno suppressive drugs or radiation. Live vaccines should not be given for at least 3 months after such treatment while inactivated vaccines given during such therapy might need to be repeated afterwards.

Childreninfectedby HIV aresusceptibleto severe and/ or recurrent infections with usual or unusual pathogens. The efficacy and safety of vaccines in such children depends on the degree of immunodeficiency.Most vacci nes are safe andefficacious in early infancy as the immune functions arerelativelyintact, but thelongevityof immune response may be affected as the disease advances, The efficacy and safety of vaccines are significantly decreased in advanced HIV disease. Vaccination of a baby born to an HIV positive mother but with an indeterminate HIV status shouldbe as per the normalschedule. Symptomatic infants should not receive BCG vaccine. Measles, MMR and varicella vaccines may be administered if the CD4 count is >15% for the age. Seroconversion should be documented following hepatitis A and hepatitis B immunization;fourdosesmayberequired indouble doses for achieving seroconversion against hepatitis B.

Splenectomy. Childrenwith splenectomy or anatomical or functional asplenia (e.g. sickle cell disease) are at an increased risk of infections with encapsulated organisms (e.g. S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, H. influenzae b). Where possible, vaccines against these organisms should be considered atleasttwoweeks before elective splenectomy.

Passive Immunization

Passive immunity is resistance based on antibodies preformed in another host. Preformed antibodies to cer tain viruses (e.g. varicella, hepatitis B) can be injected during the incubation period to limit viral multiplication. Nonspecific normal human immunoglobulin serves the same purpose when specific immunoglobulin is not available, e.g. to protect from hepatitis A or measles. Passive-active immunity involves givingboth preformed antibodies immune globulins to provide immediate protection and a vaccine to provide longterm protection, e.g. in preventing tetanus and hepatitis B. These pre-

__E_s_s__en_t_ia_1_P_e_d_ia_t_ri_c_s __________________________________

|

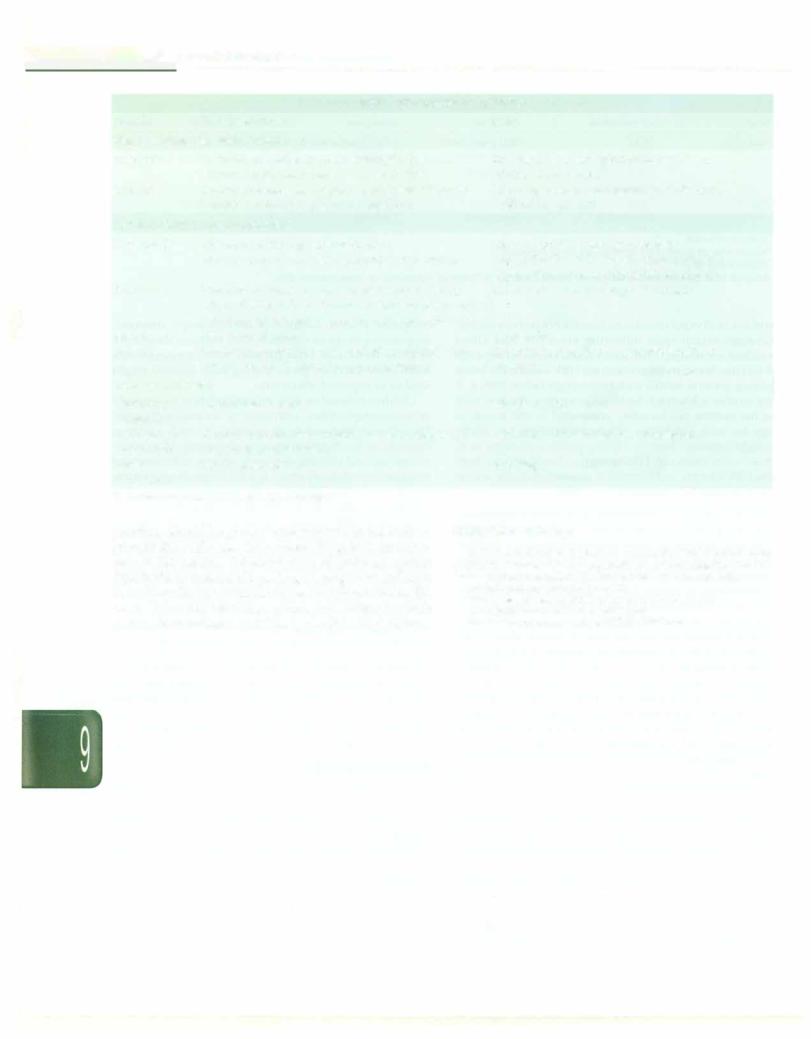

Table 9.1 O: Passive immunization |

|

Infection |

Target population |

Dose* |

Normal human immunoglobulin |

|

|

Hepatitis A |

Institutional outbreak; unimmmunized contact of |

0.02 ml/kg (3.2 mg/kg); repeat every 4 mo |

|

infected individual; travel to endemic area |

if travel is prolonged |

Measles |

Immunocompromised person or an infant <1-yr-old |

0.5 ml/kg (immunocompromised individual); |

|

exposed to infected person <6 days back |

0.25 ml/kg (infant) |

Specific (hyperimmune globulin) |

|

|

Hepatitis B |

Newborn of HBsAg positive mother |

0.5 ml (>100 IU) within 24 hr of birth |

|

Percutaneous or mucosal exposure; sexual contact |

0.06 ml/kg (32-48 JU/kg; maximum 2000 IU) |

|

|

within 7 days (preferably 48 hr) of exposure |

Varicella |

Newborn of infected mother with lesions noted 5.6 |

12.5 (5-25) U/kg (maximum 625 units) |

|

days of birth; infant <1-yr-old or immunocompromised |

|

|

child exposed to infected person <6 days back |

|

Rabies |

Bite by rabid animal |

20 units/kg |

Tetanus |

Wound/exposure in unimmunized or incompletely |

250 units for prevention; 3000-6000 units for |

|

immunized individual; treatment of tetanus |

therapy |

Antisera/Antitoxin |

|

|

Diphtheria |

Susceptible contact |

500-1000 units |

antitoxin |

|

|

Anti-tetanus |

Wound/exposure in unimmunized or incompletely |

1500 units subcutaneous or intramuscular |

serum (horse) |

immunized individual |

|

Rabies |

Bite by rabid animal |

40 IU/kg |

antiserum |

|

|

*Administered intramuscularly unless specified

parations should be given at different sites in the body to prevent the antibodies from neutralizing then immuno gens in the vaccine. Administration of antibody against diphtheria or tetanus allows large amounts of antitoxin to be immediately available to the host to neutralize the toxins. Table 9.10 tabulates common indications in which passive immunization provides protection from disease.

- Essential Pediatrics

unknown. However, fever may also be associated with adverse effects, such as increased insensible water losses, cardiopulmonarystress,paradoxicalsuppressionofimmune response and triggering of febrile seizures in predisposed patients. Reduction of fever is essential in patients with past orfamilyhistoryoffebrileseizuresandpatientswithcritically illness, cardiorespiratory failure, disturbed fluid and electrolyte balance and those with temperature exceeding 40°C (104°F). Treatment should be individualized in other patients and parental counseling is important.

The two antipyretic drugs commonly used in children are paracetamol and ibuprofen. Other agents such as aspirin, nimesulide and mefenamic acid are associated with high incidence of adverse effects and are better avoided. Therapy with ibuprofen decreases fever at the same rate as paracetamol, but therapy with ibuprofen shows a slightly lower nadir and prolonged duration of action (6 hr) as compared to paracetamol (4 hr). However, the risk of side effects such as acute renal failure and gastrointestinal bleeding is theoretically higher with ibuprofen.Conversely, theconsequences of overdose with paracetamol (hepatic failure) are more sinister than those with ibuprofen (renal failure, neurological depression). Consideringallfactors, it isreasonableto use paracetamol at a dose of 15 mg/kg every 4 hr (maximum 5-6 doses/ day) as the first-line drug for fever management. Patients who have not adequately responded to paracetamol may receive ibuprofen at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 6 hr. There is marginal benefit on amelioration of fever by combining paracetamol and ibuprofen as compared to using either drug alone without increase in toxicity. Tepid water sponging may be used as a complementary method to drug therapy in bringing down fever quickly.

Heat illness is a medical emergency. High temperatures can cause irreversible organ damage and should be brought down quickly. Since the hypothalamic set point is not altered, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which act by reducing prostaglandin production, are ineffective. External cooling with ice water sponging, cooling blankets, cold water enemas and gastric washes are helpful. Simultaneously, measures to correct the underlying condition are required.

Suggested Reading

Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: Have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 yr? Pediatrics 2001;107:1241-6

Sherman JM, Sood SK. Current challenges in the diagnosis and management of fever. Curr Opin Pediatr 2012;24(3):400-6

Short Duration Fevers

Short duration fever lasting for less than 5-7 days are among the most common reasons for pediatric outpatient visits. While the overwhelming majority are due to viral infections, fever without localizing signs or focus in children below the age of3yr (especially below3 months)

are ofgreatconcern as they may indicatea serious bactE infection. Since H. infl-uenzae and S. pneumoniae important causes of serious bacterial infection, ·, algorithms suggested below may change with increasi rates ofimmunizationwith H.infl-uenzaeand S.pneumon vaccines.

Fever without Focus in Newborns

Fever in a neonate is a medical emergency, since thei infants have 5-15% risk of serious bacterial infection sue as sepsis, bacteremia,urinary tract infections, pneumoni, enteritis and bacterial meningitis and may look we! despitecarryingaseriousinfection,delaying thediagnosi: of sepsis.

Sometimes neonates develop fever due to over clothing or warm weather ('dehydration fever'). The baby looks well and active and only requires observation with frequent feeding and nursing in less warm environment. The infant is observed for signs of sepsis and, if diagnosis is doubtful, investigated.

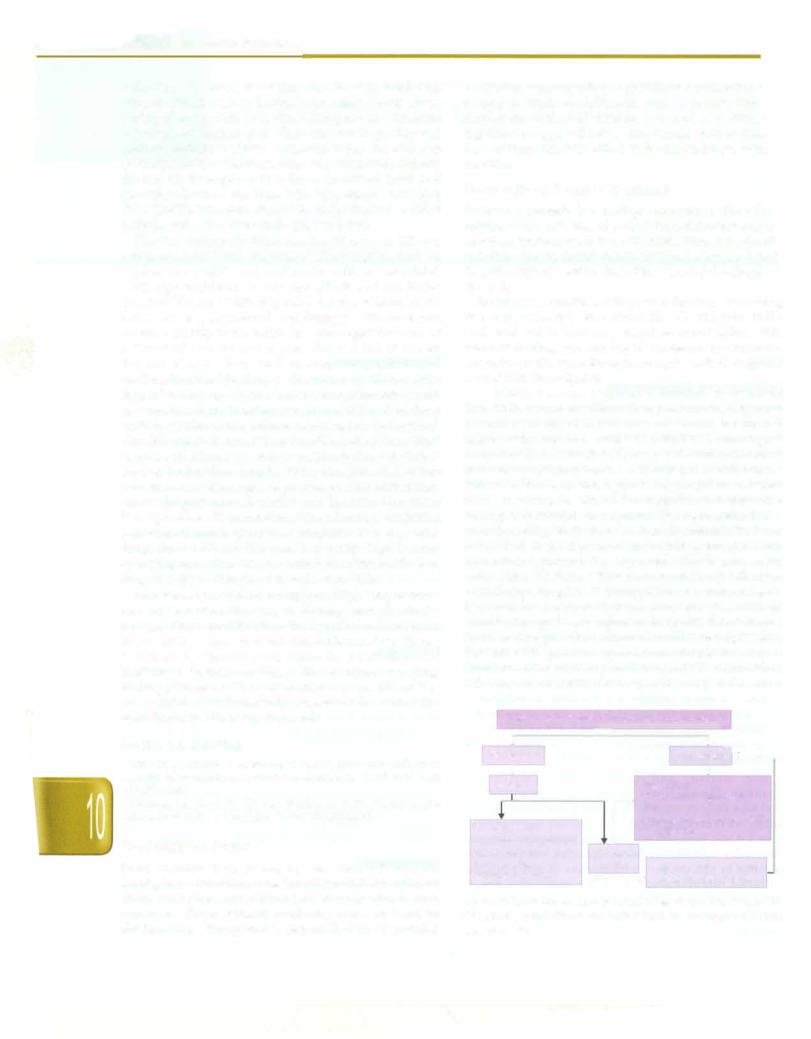

A febrile neonate requires a detailed assessment (Fig. 10.1). A neonate with toxic appearance hashigh-risk of serious bacterial infections and should be treated aggressively. He/She should be admitted to undergo a completesepsisevaluation. Therapywithantibiotics (third generation cephalosporins, e.g. cefotaxime or ceftriaxone, with or without an aminoglycoside) should be initiated while awaiting results of investigations. Supportive therapy is instituted, as required. The management of a well-appearing febrile neonate is controversial. For fever suspected to be due to overdressing, temperature assessment should be repeated 15-30 min after undressing. Most guidelines recommend hospitalization of well-appearing febrile infants below 1 month of age as they may have serious bacterial infection. These infants should undergo basic evaluation including blood counts and Creactive protein. Cultures should be sent if possible. Patients with positive septic screen should receive IV antibiotics after lumbar puncture and CSF examination. If the screen is negative, the baby is observed and a screen

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fever >38° C in less than 90 days age, no focus |

||||||

|

|

|

|

::::i |

|

|

|

Well looking |

|

|

r |

...t -, |

|||

|

|

Sick looking ----, |

|||||

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|||

Screen |

|

|

|

Hospitalize |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Blood counts, urinalysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CRP |

|

Normal screen |

|

|

|

Cultures: blood, urine, CSF |

|||

|

|

|

IV antibiotics |

||||

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

||

TLC 5000-15,000/mm |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Band count normal |

|

Abnormal |

|

|

|||

CRP negative |

|

screen |

Repeat screen if needed |

||||

Urinalysis normal |

|

----+ observe until afebrile |

|||||

|

|

|

|

||||

Fig. 10.1: Evaluation of fever in a patient less than 3-month-old; CRP (-reactive protein; CSF cerebrospinal fluid; IV intravenous; TLC total leukocyte count

repeated 6-12 hr later. If repeat screen is also negative, observationiscontinuedtillthebabyisafebrileandculture reports are available. By then most babies would have either become afebrile or a focus would have developed.

Fever without Focus in an Infant 7-3-Month-Old

Similar to neonates, 10% infants in this age group may have serious bacterial disease, with 2-3% risk of bactere mia. Also, they may look well but still have bacteremia. The algorithm for management of these babies is similar to newborns (Fig. 10.1) and includes a detailed clinical assessment. As fever may relate to immunization, history must include that of recent vaccination.

Toxic or ill-appearing babies require management similar tosickfebrile neonates. Oneto 3-month-old febrile infants who appears well should undergo a complete sepsis evaluation through the outpatient department including leukocyte and platelet counts, band cell count, C-reactive protein, urinalysis, urine and blood cultures and, if indicated, smear for malarial parasite, and chest X ray. CSF examination is undertaken if there is no clue to focus of infection. If the screen is positive, the patient is hospitalized and treated with antibiotics. A well-looking infant with no clinical focus of infection and a negative screen (leukocyte count <15,000 mm3, band count <20%, negative C-reactive protein, urine white cells <10/HPF) can be observed at home without antibiotics, provided the care takers are reliable and agree to bring the infant for reassessment 24 hr and 48 hr later.

Fever without Focus in Children 3-36-Month-Old

The risk of serious bacterial infections decreases to 5% in this agegroup.Detailedhistoryis takenaboutvaccination, history of sick contacts in the family and the condition of the child when fever is down. If the child looks toxic, he requires hospitalization and appropriate evaluation and treatment. In a nontoxic child with fever less than 39°C, one can merely observe. Children with fever more than 39°C have a high-risk of bacteremia and testing with leukocyte count and examination of smear for malarial parasite are recommended. If the leukocyte count is >15,000/mm3, bloodcultureshouldbesent and thepatient administered IV ceftriaxone on either an inpatient or outpatientbasis. A countbelow5000/mm3 suggests a viral infection or enteric fever. If the count is below 15 000 mm3 observation is continued; if fever persists bey nd 48 h; without development of a focus, evaluation should include complete blood counts, smear for malaria, urine microscopy and blood culture.

Suggested Reading

BakerMD. Evaluation and management of infantswith fever. Pediatr Clinics North Am 1999;46:1061-72

Jhaveri R, Byington CL, Klein JO, Shapiro ED. Management of the non-toxic appearing acutely febrile child. J Pediatr 2011;159:181-5

Section on clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics 2011;127:530-7

Infections and Infestations -

Fever of Unknown Origin

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is defined as fever >101°C lastingfor 3 weeks or more for which no cause is apparent after 1 week of outpatient investigation. A practical defi nition is fever >101°F measured on several occasions over a 7-day period.

Causes

The principal causes are listed in Table 10.1. Infections account for 60-70% cases in children. Most common infectious causes include entericfever,malaria, pulmonary or extrapulmonary tuberculosis and urinary tract infections. The remaining cases are due to malignancies, chiefly leukemia and autoimmune diseases, chiefly juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Uncommon causes include drugfever, temperature dysregulation,diabetesinsipidus, sarcoidosis, ectodermal dysplasia and sensory autonomic neuropathies. Even with extensive investigations, the cause remains undiagnosed in 10-20% cases.

Approach to Evaluation

The first step is to identify sick patients who need stabili zation and urgent referral. Subsequently, all attempts are made toidentifythe etiology. Adetailedhistoryis of para mountimportance.Thisshouldinclude: (i)whetherandhow fever was documented (not uncommonly, children with history of prolonged fever do not have fever documented on a thermometer); (ii) duration and pattern of fever (to distinguish fromrecurrentfever); (iii) symptomsreferable to various organ systems, weight loss; (iv) recurrent infections and/or oral thrush (suggests HIV infection);

(v)jointpain,rash,photosensitivity(autoimmunedisease);

(vi)contact with person with tuberculosis; animals (brucellosis); (vii) traveltoendemic zones (kala-azar); and

(viii)history of intake of anticholinergics (drug fever).

Complete physical examination should include documentationoffever, followed by assessmentofgeneral activity, nutrition and vital signs. Physical examination, including head to toe examination, should be repeated

Table 10.1: Causes of fever of unknown origin

Infectious

Enteric fever, malaria, urinary tract infections, tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis, HIV, occult abscesses (liver, pelvic), mastoiditis, sinusitis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, infectious mononucleosis, infective endocarditis, brucellosis, CMV, toxoplasmosis, kala-azar

Autoimmune

Systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Kawasaki disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, polyarteritis nodosa

Malignant

Leukemia, lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- |

|

s |

|

- |

|

|

------------- |

||

|

E•s•s•e •n•t-ia•l•P• e•d-ia.t.ri•c• ---------------- |

|||

|

- |

|

---- |

|

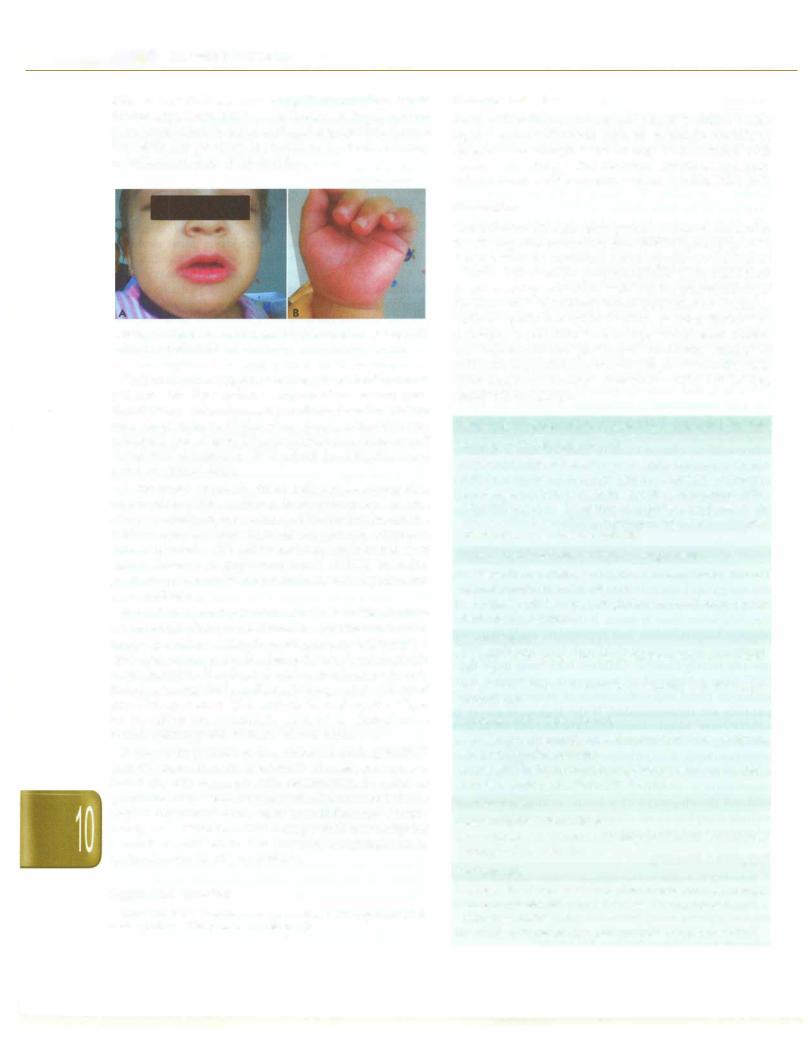

daily as new findings may emerge that provide a clue to the etiology. Kawasaki disease, though relatively uncom mon, must be kept inmindas diagnosing the illness before the tenth day of fever is crucial to prevent coronary complications (Figs 10.2A and B).

Fever with Rash

Fever with rash is a common and vexing problem. It may signify serious disorders such as meningococcemia or dengue hemorrhagic fever or may be associated with minor drug allergy. The common infectious and non infectiouscausesof fever with rash arelistedin Table 10.2.

Figs 10.2A and B: Kawasaki disease: (A) Red and cracked lips; (B) palmar rash and swelling

Preliminary investigations which should be done in all patients with FUO include complete blood counts, peri pheral smear, malarial parasite, erythrocytesedimentation rate, blood culture, Widal, chest X-ray, tuberculin test, urinalysis and culture, hepatic aminotransaminases and abdominal ultrasound. Specialized investigations are based on clinical clues.

If the above approach yields a diagnosis, appropriate treatmentshould be instituted. Inability to make a specific diagnosis merits reassessment and further investigations. While second line investigations are planned, treatment with intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone may be initiated since enteric fever is an important cause of FUO in India, particularly incaseswherepreliminary investigations are noncontributory.

Second-line investigations include HIV ELISA, contrast enhanced CT of chest and abdomen, bone marrow smear, biopsy and cultures, 20 echocardiogram, complement C3 level, antinuclearantibody, rheumatoidfactor and specific tissue biopsies, if indicated. Other serologic tests may include serology for brucellosis, HBsAg andPaul Bunnel test, Monospot test or IgM antibody to viral capsidantigen for infectious mononucleosis. Tests of no clinical value include serology and PCR for M. tuberculosis.

It should be possible to determine the etiology of FUO in most cases. In a small number of cases, no cause is found. In such cases, periodic reassessment is useful as lymphoma or systemiconsetjuvenile rheumatoidarthritis may finally surface. Some cases are self limiting. Uncom monly, use of antitubercular therapy with four drugs for a month is advised in sick patients. Empirical use of corticosteroids should be avoided.

Suggested Reading

Tolan RW. Fever of unknown origin: A diagnostic approach to this vexing problem. Clin pediatr 2010;49:207-13.

Evaluation

The nature of the rash often provides clues to determine theetiologyof theexanthematousfebrileillness (Fig. 10.3). Rashes may be macular, maculopapular, vesicular, nodular, urticaria! or purpuric (Table 10.2) and consi derable overlap may occur with varying presentations of the same etiology. Other factors that assist in diagnosis include epidemiological factors, season, history of exposure, incubation period, age, vaccination status, previous exantherns, prodromal symptoms, relation of rash with fever, distribution and progression of the rash, involvement of mucous membranes, drug intake and associated symptoms.

Table 10.2: Common exanthematous illnesses in Indian children

Macular or Maculopapular rash

Common:Measles,rubella,dengue,roseolainfantum, erythema infectiosum, drug rash, adenoviral or enteroviral infections Less common: Infectious mononucleosis, chikungunya, HIV, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, secondary syphilis, brucellosis, scrub typhus, chronic hepatitis B, cytomegalovirus, lupus, systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

Diffuse erythema with peeling or desquamation

Common: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug induced toxic epidermolysis, Kawasaki disease

Less common: Scarlet fever, staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome

Vesicular rash

Common: Chickenpox, enteroviral infections (hand-foot-mouth disease)

Less common: Herpes simplex, herpes zoster, papulonecrotic tuberculosis

Petechial and/or Purpuric rash

Common: Meningococcemia, dengue hemorrhagic fever, Henoch-Schonlein purpura

Less common: Indian spottedfever, gonococcemia, hemorrhagic measles, chickenpox, cutaneous vasculitis

Urticaria! rash

Common: Scabies, insect bites

Less common: Cutaneous larva migrans due to hookworm, strongyloides, pediculosis

Nodular rash

Common: Erythema nodosum due to tuberculosis, drugs, sarcoid, inflammatory bowel disease, lepromatous leprosy;

Molluscum contagiosum

Less common: Disseminated histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis

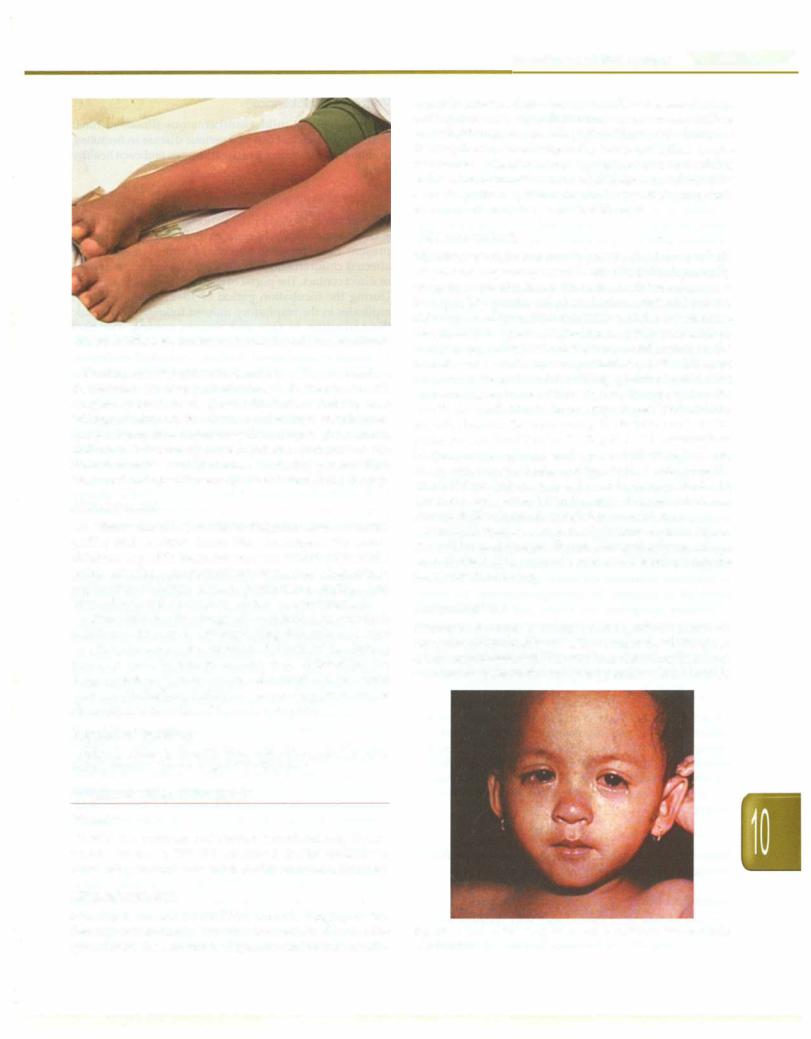

Fig. 10.3: Diffuse erythematous rash seen in a patient with dengue

Examination should include nature of the rash and its distribution, involvement of palms and soles (seen with dengue, spotted fever, Kawasaki disease and Stevens Johnson syndrome),involvement of mucous membranes, lymphadenopathy, organomegaly and signs of meningeal irritation. Laboratory investigations that may assist include complete blood counts, C-reactive protein, ESR, blood culture, specific serologies and sometimes, biopsy.

Management

All efforts should be made to diagnose serious entities earlier and institute immediate treatment. For stable children, a specific diagnosis may not be always possible. In this situation, symptomatic therapy, close observation, explanation of danger signs to parents and staying away from school until the rash resolves, is recommended.

Oftenachildreceivesdrugsandantibioticsforfeverwhich is followed by a rash. Distinguishing this rash as a viral exanthem from drug related rash is difficult. Intense itching is more commonly seen with a drug rash. Withholding the drug, symptomatic therapy and observation is the usual practice. Rechallenge with the same drug later under observation is permitted iftherash was mild.

Suggested Reading

Sarkar R, Mishra K, Garg VK. Fever with rash in a child in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereal Leprol 2012;78(3):251--62.

COMMON VIRAL INFECTIONS

Measles

Measles is a common and serious exanthematous illness, which still causes 350,000 childhood deaths annually in developing countries of which 80,000 occurinIndia alone.

Etiopathogenesis

Infections and Infestations -

4 days before to 5 days after the rash. The disease is highly contagious with secondary attack rates in susceptible household contacts exceeding 90%. The portal of entry is the respiratory tract where the virus multiplies in the respiratory epithelium. Primary viremia occurs resulting in infection of the reticuloendothelial system, followed by secondary viremia, which results in systemic symptoms. The incubation period is around 10 days.

Clinical Features

The disease is mostcommon in preschool children; infants areprotectedbytransplacentalantibodies,whichgenerally decay by 9 months (hence the rationale for vaccination at this age). The prodromal phase is characterized by fever, rhinorrhea, conjunctiva! congestion and a dry hacking cough. Koplik spots, considered as pathognomonic of measles, appear opposite the lower secondmolars on the buccalmucosa on thesecondor third day of the illness as gray or white lesions resembling grains of sand with surrounding erythema. The rash, usually apparent on the fourth day with rise in fever, appears as faint reddish macules behind the ears, along the hairline and on the posterior aspects ofthecheeks (Fig. 10.4).Therashrapidly becomes maculopapular and spreads to the face, the neck, chest, arms, trunk, thighs and legs in that order over the next 2-3 days. It then starts fading in the same order that it appeared and leaves behind branny desquamation and brownish discoloration, which fade over 10 days.

Modifiedmeasles,seen in partially immune individuals, is a milder and shorter illness. Hemorrhagic measles is characterized by a purpuric rash and bleeding from the nose, mouth or bowel.

Complications

Widespread mucosal damage and significant immuno suppression induced by measles account for the frequent complicationsseen with this viralinfection. Complications are morefrequent in the very young, malnourished and the

Measles is caused by an RNA virus belonging to the Paramyxovirus family. The virus is transmittedby droplet spread from the secretions of the nose and throat, usually

Fig. 10.4: Conjunctiva! congestion and morbilliform rash in a child with measles

-----------------------------Essential Pediatrics

immunocompromised. The most common complications are otitis media and bacterial bronchopneumonia. The usual bacterial pathogens are pneumococcus, Staphylococcus aureus and sometimes gram-negative bacteria. Other respiratory complications include laryngitis, tracheitis, bronchitis, giant cell pneumonia, bronchiectasis and flaring up of latent M. tuberculosis infection.Transient loss of tuberculin hypersensitivity reaction is common following measles. Gastrointestinal complications include persistent diarrhea, appendicitis, hepatitis and ileocolitis. Measles can precipitate malnutrition and can cause noma or gangrene of the cheeks.

Acute encephalitis occurs in measles at a frequency of 1 2- per 1000 cases, most commonly during the period of the rash, consequent to direct invasion of the brain. Post measles encephalitis occurs after recovery and is believed to be due to an immune mechanism, similar to other para infectious or demyelinating encephalomyelitis. Measles is also responsible for the almost uniformly fatal subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), seen several yr after infection at a frequency of 1 per 100,000 cases.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is clinical and may be confirmed by estimating the levels of IgM antimeasles antibody that is present 3 days after the rash and persists for 1 month. Measles needs to be differentiated from other childhood exanthematous illnesses. The rash is milder and fever less prominent in rubella, enteroviral and adenoviral infections. In roseola infantum, the rash appears once fever disappears while in measles the fever increases with rash. In rickettsial infections, the face is spared which is always involved in measles. In meningococcemia, the upper respiratory symptoms are absent and the rash rapidly becomespetechial. Drug rashes havehistory of antecedent drug intake. In Kawasaki disease, glossitis, cervical adenopathy, fissuring of lips, extreme irritability, edema of hands and scaling are distinguishing clinical features.

Treatment

Treatment is supportive and comprises antipyretics, maintenance of hygiene, ensuring adequate fluid and caloric intake and humidification. Vitamin A reduces morbidity and mortality of measles; a single oral dose of 100,000 units below 1 yr and 200,000 units over the age of 1 yr is recommended. Complications should be managed appropriately.

Prevention

Measles is a preventable and potentially eradicable disease through universal immunization (see Chapter 9).

Suggested Reading

Measles vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemic! Rec 2009; 84:349-60

Scott LA, Stone MS. Viral Exanthems. Dermatol Online J 2003;9:4

Varicella (Chickenpox)

Chickenpox is a mild exanthematous illness in most healthy children but can be a serious disease in neonates, immunocompromised, pregnant women and even healthy adults.

Etiopathogenesis

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), a DNA virus of the herpes virus family. The virus is present in respiratory secretions and skin lesions of affected children and is transmitted by air-borne spread or direct contact. The portal of entry is the respiratory tract. During the incubation period of 10-21 days, the virus replicates in the respiratory mucosa followed by viremic dissemination to skin and various organs. The host immune responses limit infection and promote recovery. In immunocompromised children, unchecked replication and dissemination of virus leads to complications. During the latter part of the incubation period, the virus is transported to the respiratory mucosa and leads to infectivity even prior to appearance of the rash. The period of infectivity lasts from 24 to 48 hr before the rash until all the vesicles are crusted (the scabs are not infective, unlike small-pox). The disease is highly contagious with secondary attack rates of 80% among household contacts. VZV establishes lifelong latent infection in the sensory ganglia. Reactivation, especially during periods of depressed immunity, leads to the dermatomal rash of herpes zoster.

Clinical Features

Chickenpox is rarely subclinical; however, in some children only a few lesions may be present. The peak age of disease is 5-10 yr. The prodromal period is short with mild to moderate fever, malaise, headache and anorexia. The rash appears 24--48 hr after the prodromal symptoms as intensely pruritic erythematous macules, seen first on the trunk. The rash rapidly spreads to the face and extremities while it evolves into papules, clear fluid-filled vesicles, clouded vesicles and then crusted vesicles (Fig. 10.5). Several crops of lesions appear and simultaneous presence of skin lesions in varying stages of evolution is characteristic of varicella. The median number of lesions is around 300 but may vary from 10 to 1500. Systemic symptoms persist for 2-4 days after appearance of the rash. The rash lasts 3-7 days and leaves behind hypopigmented or hyperpigmentedmacules that persist for days to weeks. Scarring is unusual unless lesions are secondarily infected.

Complications

Secondary bacterial infections of the skin lesions is fairly common; necrotizing fasciitis is rare. Neurologic compli cations includemeningoencephalitis, acute cerebellar ataxia, transverse myelitis, Landry-Guillain-Barre syndrome and optic neuritis. Other complications include purpura ful minans due to antibodies against protein C, CNS vasculitis