Ghai Essential Pediatrics8th

.pdf

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

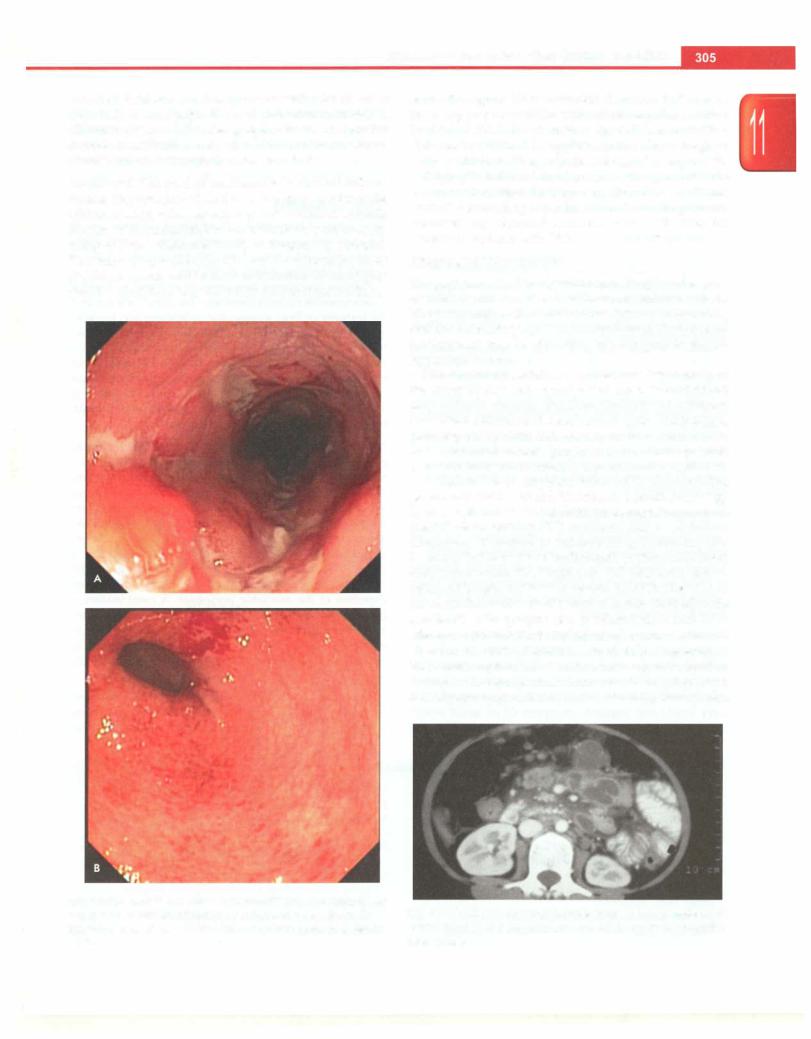

with ileal intubation and biopsy is essential for all cases (Figs 11.11 A and B). Small bowel evaluation with BMFT, CT enteroclysis or MR enterography should be done for correct classification into ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease and to determine the disease extent.

Treatment The goal of treatment is to control inflam mation, improve growth and ensure a good quality of life with the least toxic therapeutic regimen. As IBD is a chronic disease with remissions and exacerbations, proper coun seling of both patient and family at diagnosis is essential. The main drugs used for IBD are 5 aminosalicylates (5-ASA), steroids and immunomodulators (6-mercapto purine, azathioprine, methotrexate and monoclonal

antibodies against tumor necrosis factor, i.e. infliximab). Ensuring proper nutrition with caloric supplementation (-120% of RDA) is a necessity for children with IBD. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation should be given as these children are at an increased risk of osteoporosis.

Surgery is indicated in ulcerative colitis patients with severe acute colitis refractory to medical disease. Uncon trolled hemorrhage, perforation, toxic megacolon, abscesses and obstruction are the other indications for surgery in patients with IBD.

Abdominal Tuberculosis

The gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, lymph nodes and/ or solid viscera can be involved in abdominal tuberculosis. The peritoneal involvement is of two types: wet (or ascitic) and dry (or plastic) type. On the other hand, the intestinal involvement may be ulcerative, hypertrophic or ulcero hypertrophic type.

The clinical presentation is varied and depends upon the site of disease and type of pathology. Clinical features may include chronic diarrhea, features of subacute intestinal obstruction (abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, obstipation), ascites, lump in abdomen (ileocecal mass, loculated ascites, lymph nodes) and/or systemic manifestations (fever, malaise, anorexia and weight loss).

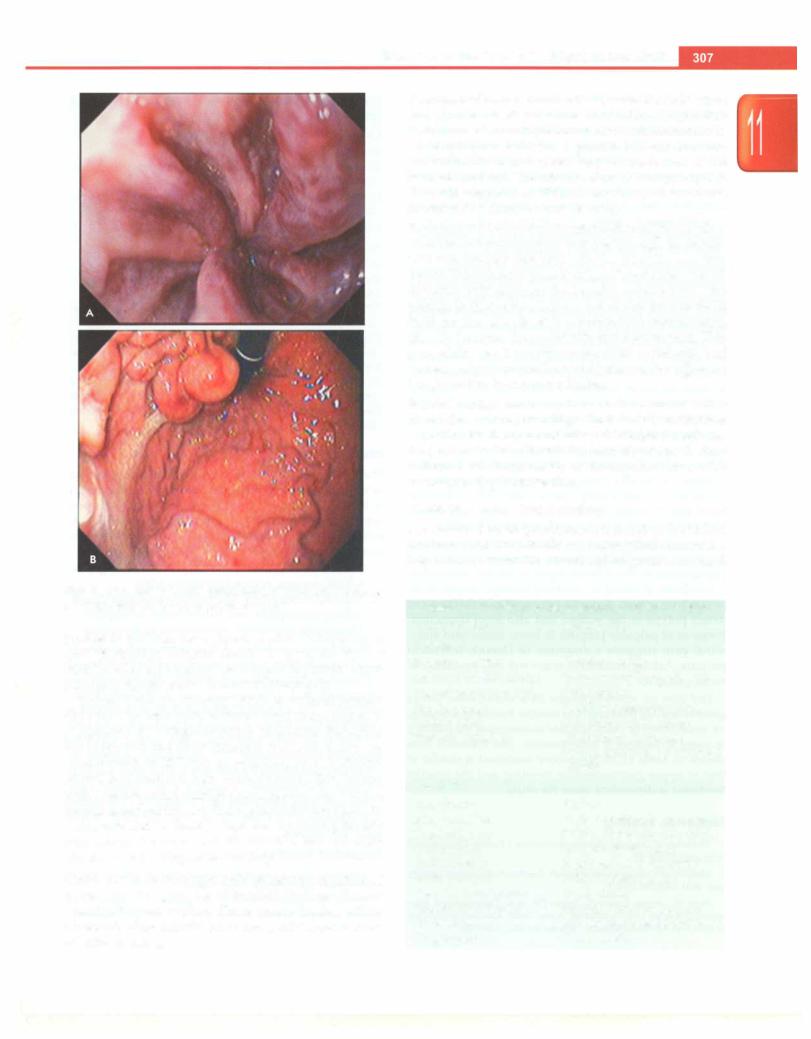

A high index of suspicion followed by documenting presence of acid fast bacilli (fine needle aspiration cytology from lymph nodes, ascitic fluid, endoscopic biopsies) on Ziehl-Neelsen staining, PCR or culture leads to a definitive diagnosis. Presence of tubercular granuloma with caseation in the biopsies (endoscopic, peritoneal or liver) also helps make the diagnosis. CT abdomen shows enlarged lymph nodes with central necrosis (Fig. 11.12). An exudative ascites (low serum to ascitic fluid albumin gradient) with lymphocyte predominance and high adenosine deaminase is typical of tubercular ascites. In absence of above features, a probable diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis is made when suggestive clinical features and response to antitubercular therapy is present. It is important to differentiate intestinal TB from Crohn

Figs 11.11A and B: Inflammatory bowel disease. (A) Deep, linear, serpigenous ulcers on colonoscopy in Crohn disease; (B) confluent superficial ulcerations with friability on colonoscopy in ulcerative colitis

Fig. 11.12: CT scan showing multiple enlarged lymph nodes with central necrosis in para-aortic and mesenteric region in abdominal tuberculosis

___E_s_s_e_n_ tia_i_P_e_d_ ia _trics_________________________________

disease as they mimic each other in clinical presentation but have different treatments.

Antitubercular drugs are the mainstay of treatment. Surgery is indicated if there is bowel perforation, obstruction or massive hemorrhage. One should suspect multidrug resistant tuberculosis in patients with a definite diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis but a poor response to standard antitubercular therapy.

Suggested Reading

Braamskamp MJ, Dolman KM, Tabbers MM. Clinical practice. Pro tein-losing enteropathy in children. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:1179-85

du Toit G, Meyer R, Shah N, et al. Identifying and managing cow milk protein allergy. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2010;95:134-44

Feasey NA, Healey P, Gordon MA. Review article: the etiology, investigation and management of diarrhea in the HIV-positive patient. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:587---{;03

Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szab6 TR, European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:136-60

Poddar U, Yachha SK, Krishnani N, Srivastava A. Cow milk protein allergy: Anentity forrecognitionin developingcountries. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:178-82

Sandhu BK, Fell JM, Beattie RM, et al. on Behalf of the IBO Working Group of the BritishSociety of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Guidelines for the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children in the United Kingdom. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Feb;50:Sl-S13

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a commonly encountered problem in children. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as bleeding from a site proximal to the ligament of Treitz (at the level of duodenojejunal flexure). Lower gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as bleeding from a site distal to ligament of Treitz.

Hematemesis is passage of blood in vomiting and suggests an upper GI site of bleeding. The vomitus may be bright red or coffee-ground in color depending upon the severity of hemorrhage and the duration it stayed in contact with gastric secretions. Melena is passage of black tarry stools and suggests an upper GI or small bowel source of bleed. Hematochezia is passage of bright red blood

in stools. Hemobilia refers to bleeding from the biliary tree while pseudohematobilia is bleeding from the pancreas. Obscure GI bleed is defined as bleeding from gastro intestinal tract that persists or recurs without any obvious etiology after a diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy. It accounts for -5% of all GI bleeds.

Upper GI Bleeding

The causes of hemorrhage from upper GI tract vary in different age groups as shown in Table 11.18. Varices, esophagitis and gastritis are the commonest causes of upper GI bleeding in Indian children.

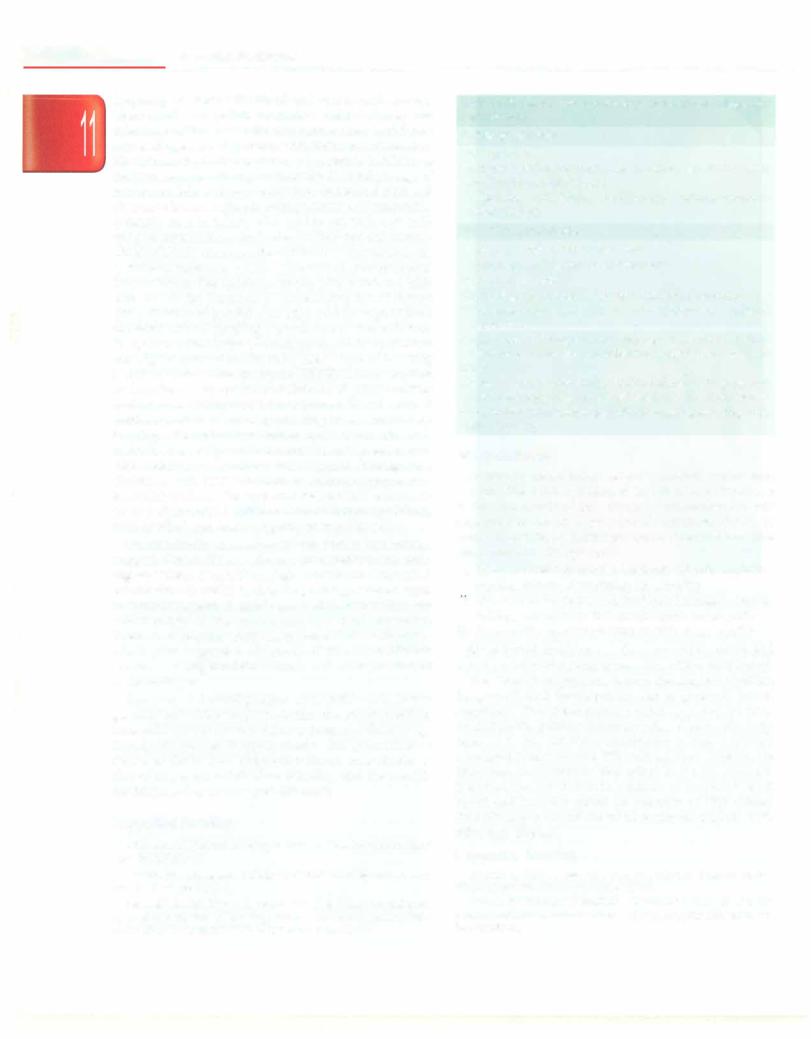

Painless passage of large amount of blood in vomitus points towards variceal bleeding. One should always look for features of liver disease like splenomegaly, jaundice and ascites. In portal hypertension, the spleen may reduce in size just after a bout of massive hematemesis and is thus missed on examination. In a child with portal hypertension, esophageal varices are the commonest cause of upper GI bleeding (Fig. 11.13A). Gastric varices (Fig. ll.13B), congestive gastropathy and gastric antral vascular ectasia can also present with hematemesis.

Management. General supportive measures, including establishing a good venous access, intake output monitoring, oxygen supplementation (if required) and charting of vital signs are mandatory. Blood transfusion should be given to achieve hemoglobin of 8 g/dl. Short term antibiotic prophylaxis (third generation cephalo sporin for 7 days) may reduce bacterial infection and variceal rebleeding, and should be administered in children with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. Specific treatment depends upon the patient's condition and expertise of the available personnel. A combination of pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy is preferred. Early administration of vasoactive drugs should be followed by endoscopic therapy within 12 hr of bleed. Following an episode of acute variceal bleeding, all patients should receive secondary prophylaxis to prevent rebleeding.

Administration of somatostatin or octreotide decreases the splanchnic and azygous blood flow, thus reducing portal pressures. Both agents are equally effective; limited

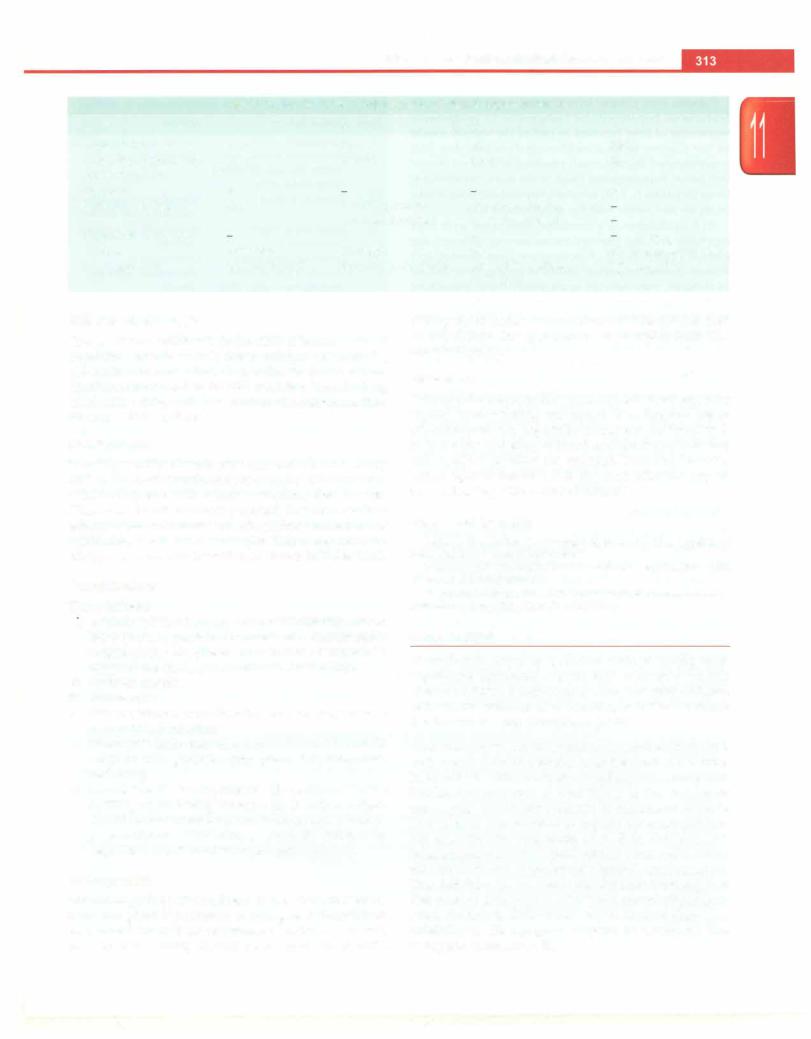

Table 11.18: Causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Neonate or infant

Swallowed maternal blood Esophagitis

Gastroduodenal erosion or ulceration Sepsis or coagulopathy Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn Esophageal varices (children >4 mo) Vascular malformation

Foreign body impaction

Rare: Antral/duodenal web, gastric cardia prolapse, heterotopic pancreatic tissue, esophageal duplication

Children >2 yr

Esophagitis due to reflux, medications, infections Mallory-Weiss tear

Gastric erosions; duodenal or gastric ulcer

Portal hypertension causing esophageal/gastric varices; congestive gastropathy; gastric antral vascular ectasia Caustic ingestion, foreign body impaction

Vascular malformation, Henoch-Schonlein purpura Tumors: leiomyoma, lymphoma

Rare: gastrointestinal duplication, hemobilia, radiation gastritis, coagulopathy

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

Figs 11.13A and B: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing

(A) esophageal varices; (B) large gastric varices

studies in children have shown control of bleeding in 64-71% children. Infusion should be given for at least 24-48 hr after the bleeding has stopped to prevent recur rence and should not be discontinued abruptly.

Endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) or variceal ligation (EVL) are the two main methods used to manage eso phageal varices. Using a fiberoptic endoscope, the varices are inspected and their location, size and extent are documented. In EST, 2-3 ml of sclerosant (1% ethoxy sclerol) is injected into each variceal column. EVL is done with a device called multiple band ligator. The variceal column is sucked into a cylinder attached at the tip of the endoscope and the band is deployed by pulling the trip wire around the varix. Both EST and EVL have 90-100% efficacy in controlling acute bleeding.

Gastric varices are managed with endoscopic injection of tissue adhesive glue, i.e. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate or isobutyl-2-cyanoacrylate. These agents harden within 20 seconds of contact with blood andresult in rapid control of active bleeding.

Tamponade ofvarices is required only when the endoscopic and pharmacologic measures have failed. Sengstaken Blakemore tube is a triple lumen tube with connection to an esophageal balloon, a gastric balloon and one perforated distal end which helps in aspiration of the stomach contents. The tube is relatively cheap, requires little skill compared to EST and has efficacy of above 75% in controlling acute variceal bleeding.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) involves insertion of a multipurpose catheter through the jugular vein and superior vena cava with the aid of the puncture device.The catheter ispassed viahepatic vein into a branch of portal vein through the hepatic parenchyma. The passage is dilated by a balloon and an expansile metallic mesh prosthesis is placed to maintain the communication directly between the portal vein and hepatic vein. This procedure results in bypassing liver resistance and consequently decreases the portal pressure. Experience of this procedure in children is limited.

Surgical management is required when above measures have failed or when bleeding is from ectopic varices that cannot be effectivelycontrolled byendoscopicprocedures. Surgery can be done either in the form of portocaval shunt (selective or nonselective) or devascularization with esophageal staple transection.

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

The causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in children are shown in Table 11.19. History and physical examination helps narrow down the differential diagnosis. Increased

Table 11.19: Causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Neonate or infant |

Children >2 yr |

Colitis |

|

Infectious colitis |

Infectious colitis |

Cow milk protein allergy |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

Necrotising enterocolitis |

Tuberculosis |

Hirschsprung |

Pseudomembranous colitis |

enterocolitis |

Cow milk protein allergy |

Systemic vasculitis |

Uncommon: Amebiasis, |

|

cytomegalovirus, neutropenic |

|

colitis |

Noncolitic |

|

Anal fissure |

Fissure |

Intussusception |

Polyp or polyposis syndrome |

Duplication cyst |

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome |

Arteriovenous |

Meckel's diverticulum |

malformation |

Rectal varices or colopathy |

Rectal prolapse |

NSAID induced ulcer |

Meckel's diverticulum |

Hemorrhoids |

Hemorrhagic disease |

Henoch-Schonlein purpura |

of newborn |

Arteriovenous malformation |

Coagulopathy |

Coagulopathy |

--------------------------------Essential Pediatrics

frequency of stools with blood and mucus with crampy abdominal pain points towards a colitic illness and infectious colitis is by far the commonest cause in children across all ages. A sick preterm with abdominal distension, blood in stools, feed intolerance and systemic instability is likely to have necrotizing enterocolitis.Delayed passage of meconium followed by constipation, abdominal pain and distension is seen in Hirschsprung's disease. Allergic colitis is mostly seen in infants who are top fed with cow milk andpresent withloosestoolsmixed with blood and anemia. Onset ofbloodydiarrhea afterantibioticuse points towards pseudomembranous colitis. Presence of extraintestinal manifestations like aphthous ulcers, joint pains and iritis gives clue to the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). History of painful defecation and passage of hard stools with blood streaking of stools is seen in anal fissure. In a patient with history of constipation, straining at stools and digital evacuation, the most likely cause of bleeding is solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS). Intussusception is characterized by episodes of abdominal pain, vomiting and red currant-jelly stools, i.e. mixture of blood, mucoid exudates and stool. Painless bleeding is seen commonly in polyps, Meckel's diverticulum, ulcer or vascular ano maly. Presence of typical cutaneous lesions as seen in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome often suggests the diagnosis. Children with HIV infection or immunosuppression secondary to chemotherapy can develop CMV enterocoli tis or polymicrobial inflammation of cecum (typhlitis), both of which can lead to significant rectal bleeding.

On examination, presence offissureandfleshyanal tags suggests Crohn disease whereas characteristic orobuccal pigmentationis seeninPeutz-Jeghersyndrome.Abdominal examination is useful in detecting sausage shaped mass in intussusception. A gentle per rectal examination can detect polyps in the rectum and also stool impaction. Presence of palpable purpura in lower limbs with abdo minal pain suggests a diagnosis of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Asking the child to strain will show presence of rectal prolapse.

The aim of investigations in a child with lower gastrointestinal bleeding isto localize the site of bleeding, i.e.small bowel orcolonand also todeterminethe etiology in order to manage it appropriately. The approach is as shown in Table 11.20. Supportive treatment is similar to that of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and the specific treatment is dependent upon the cause.

Suggested Reading

Molleston JP. Variceal bleeding in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003;37:538-45

MurphyMS. Management ofbloody diarrhea in children in primary care. BMJ 2008;336:1010-5

Sarin SK, Ashish Kumar A, Angus PW, et al. Diagnosis and man agement of acute variceal bleeding: Asian PacificAssociation for Study of the Liver Recommendations. Hepatol Int 2011;5:607-24

Table 11.20: Evaluation for etiology of lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding

Colitic presentation

Hemogram, ESR

Stool examination for trophozoites, culture sensitivity, assay for Clostridium difficile toxin

Colonoscopy with biopsy for histology, culture, immuno- histochemistry

Noncolitic presentation

Hemogram, ESR, prothrombin time Colonoscopy and biopsy or polypectomy

Based on presentation

Ultrasonography abdomen (suspected intussusception) 99mTc pertechnate scan (Meckel diverticulum or intestinal duplication)

Triple phase CT angiography and selective cannulation of mesenteric vessel for embolization (ongoing aneurysmal bleed)

Wireless capsule endoscopy, double balloon endoscopy and push endoscopy (obscure site of bleeding in the small bowel) Preoperative enteroscopy (significant ongoing bleeding from unknown site)

Intestinal Failure

Ther term intestinal failure refers to a malabsorptive state in which the residual intestinal function is inadequate. It is the end result of any disease that causes chronic dependence on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) to maintain growth, hydration or micronutrient balance. The most common etiologies are:

i.Short bowel syndrome: Midgut volvulus, gastro schisis, trauma, necrotizing enterocolitis

u.Mucosal enteropathy: Microvillous inclusion disease, tufting enteropathy and autoimmune enteropathy.

iii.Dysmotility syndrome: neuropathic or myopathic

Short bowel syndrome is the commonest cause and usually results from surgicalresection of the small bowel.

The aim of management is toprovideadequatenutrition for growth and development and to promote bowel adaptation. The identification of etiology is important as conditions like primary enterocyte disorders require early referral to an intestinal transplant centre. Catheter associated infections and TPN related liver diseases are important complications that affect long term survival. Intestinal transplantation in isolation or combined small bowel and liver transplant (in presence of TPN related liver disease) is the treatment of choice for patients with refractory disease.

Suggested Reading

Avitzur Y, Grant D. Intestine transplantation in children: update 2010. Pediatr Clin North Am 2010;57:415-31

Malone FR, Horslen SP Medical and surgical management of the pediatricpatientwith intestinalfailure. Curr TreatOptionsGastroenterol 2007;10:379-90

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

DISORDERS OF THE HEPATOBILIARY SYSTEM

The liver has immense regenerative capacity and plays a vital role in maintainingnormal body metabolism. It stores excess carbohydrates as glycogen and releases glucose during fasting by glycogenolysis or gluconeogenesis. It also synthesizes proteins like albumin, fibrinogen, transferrin, low-density lipoproteins, ceruloplasmin and complement and coagulation factors. The liver is also responsible for lipid metabolism by fatty acid oxidation and detoxification of drugs. The primary bile acids, cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid, are synthesized in liver and excreted in bile which helps in bile flow and fat absorption. Hepatomegaly, jaundice, pruritus, growth failure, portal hypertension (splenomegaly and ascites), varicealbleeding and hepatic encephalopathy are common manifestations of liver disease in children.

The reference range for prothrombin time is usually around 11-16 seconds; the normal range for the INR is 0.8-1.2. A prolongation of PT by >3 seconds is abnormal.

Serum proteins. The half-life of albumin is 20 days; albumin is a marker of liver synthetic functions and is low in chronic liver disease. Gamma globulins are increased in autoimmune hepatitis; the ratio of albumin to globulin is reversed in cirrhosis, particularly in autoimmune liver disease. Low serum albumin and prolonged PT (un responsive to vitamin K) indicate poor synthetic liver functions, raised ALT and AST indicate inflammation and raised ALP and GGT suggest cholestasis.

Serum ammonia levels. Levels are raised in hepatic encephalopathy.

Cholesterol. Levels are increased in cholestasis.

Evaluation

After accurate history and physical examination, a judicious selection of laboratory tests helps in arriving to a definite diagnosis.

Biochemical Tests

Bilirubin. Total and fractionated (unconjugated and conjugated) bilirubin helps to differentiate between elevation caused by hemolysis versus hepatocellular or biliary dysfunction.

Transaminases (aspartate aminotransferaseor serumglutamate oxaloacetate trans/erase (AST, SCOT) and alanine amino transferaseorserumglutamatepyruvatetrans/erase(ALT,SGPT).

ALT is present mainly in liver and in lower concentration in muscle while AST is derived from other organs as well (muscles, kidney, red blood cells). Most marked increase in transaminases occurs with acute hepatocellular injury secondarytoinflammationor ischemia, while inchronic liver disease transaminases are mildly or moderately elevated.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Normal values are higher in growing children due to bone isoenzyme fraction. If elevation is associated with increased gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), it suggests cholestasis. GGT is more specific for hepatobiliary disease. The values are higher in newborns and reach normal adult values by 6-9 months.

Prothrombin time (PT) and international normalized ratio

(INR). Deficiency of factors V and vitamin K dependent factors (II, VII, IX and X) occurs in liver disease. PT is a marker of synthetic function of liver. lNR is a standardized way of reporting the prothrombin time. It is the ratio of a patient prothrombin time to a normal sample, raised to the power of the international sensitivity index (ISi) value for the analytical system used. ISi ranges between 1.0 and 2.0 and shows how a batch of tissue factor compares to an internationally standardized sample.

INR = (PT test/PT normal)151

Radiological Tests

X-ray abdomen. Hepatomegaly, calcification in space occupying lesions in liver, air under the diaphragm (pneumoperitoneum) or in a space occupying lesion (liver abscess) or in portal vein (necrotizing enterocolitis) can be seen on plain X-ray of the abdomen.

Ultrasonography. It is an extremely useful, cost effective and easily available imaging tool. It provides information regarding: (i) liver and spleen size, echotexture and space occupying lesion, (ii) splenoportal axis and hepatic venous system by Doppler ultrasonography, (iii) ascites, lymph nodes, and (iv) gallbladder, biliary tree and pancreas.

CT scan. It provides information similar to ultrasono graphy and has the advantage of better resolution especially for evaluation of pancreas, focal lesions like cysts and tumors and vascularity of a lesion following intravenous contrast injection. CT allows visualization at different levels by selecting cuts through the organs and reconstruction in axial planes.

Radionuclide scanning. This technique depends on selective uptake of radiopharmaceutical agent, its pattern and excretion. 99mTc iminodiacetic acid is taken up by hepato cytes and excreted in bile. It is useful in the assessment of neonatal cholestasis, acute cholecystitis and bile duct perforation.

Cho/angiography. It is the direct visualization of the biliary tree after contrast injection. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are commonly done. Sometimes cholangiography is done by the percutaneous transhepatic route.

Liver Biopsy

Biopsy, using a Trucut needle or Bard biopsy gun, is a useful investigation for making a histologic diagnosis especially in neonatal cholestasis, congenital hepatic fibrosis, storage disorders like glycogen storage diseases

- |

E_sse_nt a l |

e |

at |

s |

|

L |

... _ |

_ i__P_d_iicr_ ---------------------------------- |

|||

and histiocytosis. It is useful for enzymatic estimation in metabolic diseases and for copper in Wilson disease. It is helpful in diagnosis of infectious diseases by immuno histochemistry and monitoring response to therapy in autoimmune liver disease. Liver biopsy also helps in understandingthestage ofliverdisease, e.g.chronichepa titis or cirrhosis, degree of fibrosis and inflammation. Contraindications of liver biopsy are presence of deranged coagulation (prolonged INR, decreased plate lets), ascites or large vascular or cystic lesions in theliver. Complications include intraperitoneal hemorrhage, hematoma formation, bile leak and pneumothorax (see Chapter 28).

Hepatomegaly

A palpable liver does not always indicateenlargement. It onlyreflectstherelationof the liver to adjacent structures. In normal children, the liver is palpable one cm and in infantsupto2cmbelowthecostalmargin.Whenthe costal angle is wide, liver may not be palpable and may be more than2cmbelow theribmarginifthecostalangleisnarrow. Liver is pusheddown in pneumothorax, bronchiolitis and emphysema. Visceroptosis associated with rickets and Riedel lobe cause pitfalls in the interpretation of the liver size. It is therefore important to measure the liver span to determine the presence of hepatomegaly. The liver span varies with age: infants 5-6.5 cm; 1-5 yr; 6-7 cm; 5-10 yr; 7-9 cm; and 10-15 yr; 8-10 cm. The liver is also examined for tenderness, consistency and character of the surface. Abdomen should be palpated for other masses or enlargement of the spleen. The liver may be enlarged due to: (i) inflammation, (ii) fatty infiltration, (iii) Kupffer cell hyperplasia, (iv) congestion, (v) cellular infiltration, and (vi) storage of metabolite (Table 11.21).

Splenomegaly

Common causes ofsplenomegalyare listed inTable 11.22. The spleen is massively enlarged, >8 cm or crossing the umbilicus in the following conditions:

Table 11.21: Causes of hepatomegaly

Chronic liver disease(cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis): Wilson disease, chronic hepatitis B and C, autoimmune liver disease, Budd Chiari syndrome, cryptogenic

Metabolic or storage disorders: Glycogen storagedisease,Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease, progressive familial intra hepatic cholestasis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Infective: Viral hepatitis, liver abscess (pyogenic or amebic), tuberculosis, salmonella, malaria, kala-azar, hydatid disease

Tumors: Lymphoma, leukemia, histiocytosis, neuroblastoma, benign hemangioendothelioma, mesenchymal hamartoma, hepatoblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma

Biliary: Caroli disease, choledochal cyst, congenital hepatic fibrosis,cysticdiseaseof liver; extrahepatic biliary obstruction

Miscellaneous: Congestive heart failure, constrictive peri carditis, sarcoidosis

Table 11.22: Common causes of splenomegaly

Portal hypertension: Cirrhosis, extrahepatic portal venous obstruction; congenital hepatic fibrosis, noncirrhotic portal fibrosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome

Storage disorders: Niemann-Pick disease, Gaucher disease, mucopolysaccharidosis

Hematological malignancies: Leukemia, lymphoma, histiocytosis

Increased splenic function: Collagen vascular disorders, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, inherited hemolytic anemias

Infections: Malaria, enteric fever, viral hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, kala-azar; congenital infections

Extramedullary he111atopoiesis: Osteopetrosis

i.Noncirrhotic portal hypertension due to extrahepatic portal venous obstruction, congenital hepatic fibrosis and noncirrhotic portal fibrosis

ii.Hematologicmalignancies: chronicmyeloid leukemia,

myeloproliferative disorders; splenic lymphoma

m.Osteopetrosis

iv.Hemolytic anemia: thalassemia major v. Storage disorders: Gaucher disease

v1. Infections: kala-azar, chronic malaria; congenital syphilis.

Liver Abscess

Pyogenic liver abscess is more common than amebic liver abscess in children. The infection reaches the liver by one of the following routes: (i) portal vein, e.g. in intra-abdo minal sepsis, umbilical vein infection; (ii) biliary tree obs truction and cholangitis, e.g. choledochal cyst;

(iii)systemic sepsis, e.g. endocarditis, osteomyelitis; and

(iv)direct inoculation, e.g. in trauma. In children on immunosuppressive medications or with defects of neutrophil function, e.g. chronic granulomatous disease) there is an increased risk of developing abscesses, especially due to S. aureus.

Invasive intestinal amebiasis can lead to amebic liver abscess althoughahistoryofamebiccolitisinthepreceding period is not common. Amebic liver abscess is usually solitary and in the right lobe of liver whereas pyogenic abscesses may be multiple (secondary to cholangitis) or single. Nearly three quarters of pyogenic liver abscesses are in the right lobe of liver.

Clinical features. The child presents with fever and right upper quadrant abdominal pain.Jaundice is uncommon. Examination reveals tender hepatomegaly. Empyema, pneumonia, subphrenic abscessand cholecystitiscan have asimilarclinicalpresentationand should be differentiated. Complications include spontaneous rupture into perito neum,pericardium,pleuraor bronchial tree and metastatic spread to lungs or brain.

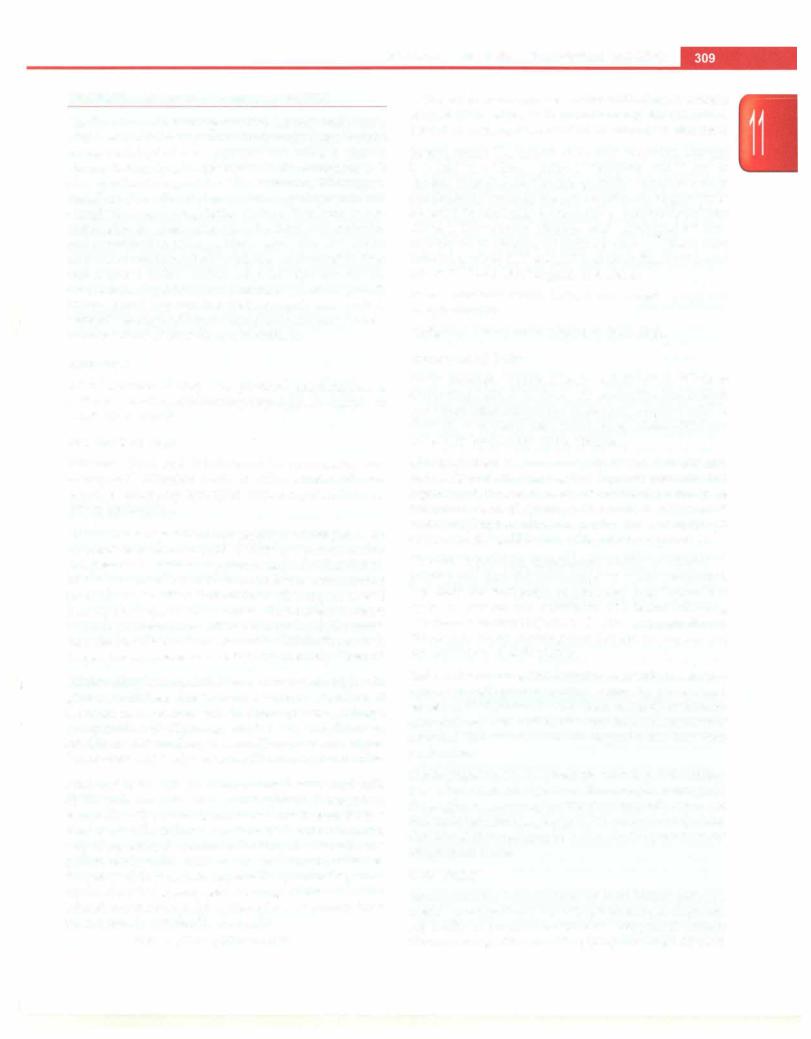

Diagnosis. Leukocytosis and elevated ESR are usually present. Transaminases and alkaline phosphatase are mildly elevated. X-ray abdomen shows an elevated right

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

dome of diaphragm with or without pleural effusion. Diagnosis is confirmed by imaging; ultrasound provides good details about abscess size, number, rim and liquefaction. Contrast enhanced CT scanmay be required in patients with complications (Fig. 11.14). Amebic serology (indirect hemagglutination test) is positive in >95% children with amebic liver abscess and helps to differentiate it from pyogenic abscess.

Management. Patients with pyogenic liver abscesses are treated with broad spectrum antibiotics (against gram positive, gram-negative aerobic and anerobic bacteria) for 4-6 weeks.Metronidazoleisusedfor10-14daysin patients with amebic liver abscess. Ultrasound guided percuta neous needle aspiration and/or catheter drainage is requiredfor abscessesthatfail toimproveafter3--4daysof antibiotic therapy, large abscesses in left lobeand impen ding rupture (narrow rim <1 cm). Surgery is required for abscesses complicated by frank intraperitoneal rupture or multiseptate abscesses not responding to percutaneous catheterdrainage and antibiotics.

Prognosis. The abscess cavity takes3-6 months to resolve completely. Cure rate following management with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage is excellent.

Liver Tumors

Liver tumors account for -0.5-2% of all neoplasms in children. Hepatoblastoma, hemangioendothelioma and mesenchymal hamartoma are seen primarily in young children whereas hepatocellular carcinoma, undiffer entiated embryonal sarcoma and focal nodular hyper plasiapresentintheolderchild.Themost commontumors are hepatoblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and infantile hemangioendothelioma.

Fig. 11.14: Computed tomography scan shows a multiloculated liver abscess in the right lobe (black arrow) with elevated right dome of diaphragm and ascites. Percutaneous drainage catheter is seen in situ (white arrow)

Infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma isa benigntumorand presents in first 6 months of life with an abdominal mass. Jaundice, skin hemangiomas and congestive heart failure may be associated. The lesion may be single or multiple and is made of thin vascular channels. Observation is recommended for focal lesions. Treatment options for multifocal and diffuse lesions include corticosteroids, hepatic artery ligation with or without corticosteroids, hepatic artery embolization, surgical resection or liver transplantation.

Hepatoblastoma is the mostcommonmalignant liver tumor in children. It is of two types: epithelial (fetal or embryonal malignant cells) and mixed (epithelial and mesenchymal elements) and presents with an abdominal mass and anorexia. Weight lossandpain in abdomen usually appear late; metastasis occurs to lungs and lymph nodes and alphafetoprotein is raised in the majority of cases. Ultrasound helps to differentiate between malignant and vascular lesions. CT and MRI are used to define tumor extent and resectability. The survival of patients with a hepatoblastoma has markedly improved in recent years by combining surgery with preand postoperative chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin and doxo rubicin.Livertransplantationisan option for unresectable hepatoblastoma following chemotherapy in absence of visible extrahepatic disease.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is usually multicentric. The risk is increased in patients with chronic hepatitis B or C infection, tyrosinemia, glycogen storage disease or prior androgen therapy. The tumor presents asa liver mass with abdominal distension, anorexia and weight loss. Liver functions areusuallynormalandanemia may be present; alphafetoprotein is raised. Imaging with CT/MRI helps in targeting the tumor for needle biopsy, confirming the diagnosis and determining resectability. Bone scan and CT chest should be done to screen for metastasis. Treatment options include surgical resection along with chemotherapy; chemoembolization and liver trans plantation.

Suggested Reading

Srivastava A, Yachha SK, Arora V, Poddar U, Lal R, Baijal 55. Iden tification of high-risk group and therapeutic options in children with

liver abscess. Eur J Pediatr 2012;171:33-41

von Schweinitz D. Hepatoblastoma: recent developments in research and treatment. Semin Pediatr Surg 2012;21:21-30

Jaundice

The term jaundice means a yellow discoloration of skin, sclera andmucousmembranedue toincreasein theserum bilirubin levels. Nearly 250-300 mg of bilirubin is produced daily, approximately 70% from breakdown of old erythrocytes in reticuloendothelial system. Bilirubin is cleared by the liver in three steps. It is first transported into hepatocytes by specificcarriers. Then it is conjugated

___E_s_s_e_n_ tia_i_P_e_d_ i_a _tr_sic_________________________________

to 1-2moleculesofglucoronide.Thereafter the conjugated bilirubin moves to the canalicular membrane where it is excreted into the bile canaliculi by other carrier proteins. Most of the conjugated bilirubin is excreted in the stool and small amount is reabsorbed after deconjugation by colonic bacteria. Colonic bacteria also reduce bilirubin to urobilinogen, which is reabsorbed and excreted in urine.

Serum bilirubin should be >2.5-5 mg/dl for jaundice to be visible. Hyperbilirubinemia is classified as uncon jugated (conjugated bilirubin fraction <15% of total bili rubin and normal colored urine) and conjugated hyper bilirubinemia (conjugated bilirubin fraction >20% with high colored urine). Conjugated bilirubin is cleared by kidneys;thusinrenalfailure, bilirubinlevelsareincreased. Any abnormality of the above steps can cause jaundice (Table 11.23).

Congenital Enzyme Deficiencies

Gilbert syndrome is the most common cause of uncon jugated hyperbilirubinemia and affects 3-8% of the population. It results from a partial deficiency of the enzyme uridine diphosphate glucuronyl transferase (UDP-GT) and thus, impaired conjugation. Most patients are asymptomatic and exhibit chronic or recurrent jaundice (up to 6 mg/dl) precipitated by intercurrent illness, fasting or stress. Mild fatigue, nausea, anorexia or abdominal pain may be present in some patients. Other liver functions remain normal. No specific treatment is necessary for this disorder.

Crigler-Najjarsyndrome (CN) type Iisanautosomalrecessive disorder characterized by absence of UDP-GT activity.

Table 11.23 Causes ofjaundice in children

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia

Hemolysis: Blood group incompatibility (Rh, ABO), drugs, infection related, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, autoimmune hemolysis

Bilirubin overproduction: Ineffective erythropoiesis, large hematoma

Specific conditions in neonates: Physiologicjaundice, breastmilk jaundice

Enzyme defects: Gilbert syndrome, Crigler-Najjar syndrome Miscellaneous: Hypothyroidism, fasting

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia

Neonatal cholestasis

Infections: Sepsis, acute viral hepatitis, enteric fever, malaria, leptospirosis

Chronic liver disease

Liver tumor: Primary, secondaries Infiltration: Histiocytosis, leukemia

Enzyme defects: Dubin-Johnson syndrome, Rotor syndrome Biliary: Choledochal cyst, choledocolithiasis, ascariasis, sclerosing cholangitis

Miscellaneous: Drug toxicity (hepatocellular, cholestatic), total parenteral nutrition, veno-occlusive disease

Patients developsevere unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia anddieby18-24 months of age if untreated. Phototherapy, plasmapheresis andexchange transfusion are requiredfor managing these cases in initial phases. Serum bilirubin levels should be kept below 20 mg/dl during first several months of life to prevent brain damage. Definitive treatment is possible by liver transplantation, preferably auxiliary, if available.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type II is also known as Aria syndrome. There is marked reduction of UDP-GT. In comparison to typeI, jaundice is less severe and does not result in kernicterus. The condition responds to drugs like phenobarbitone that stimulate hyperplasia of the endoplasmic reticulum. The bilirubin level significantly decreases in type II CN following administration of phenobarbitone, while no change is seen in typeI patients.

Dubin-Johnsonsyndrome is anautosomalrecessivedisorder resulting from impaired hepatic excretion of bilirubin and causes conjugated hyperbilirubinemia (2-6 mg/dl). The transaminases and synthetic liver functions are normal. Most patients are asymptomatic apart from jaundice. Pregnancy and oral contraceptives may worsen jaundice. Liver biopsy is often done for exclusion of other causes and shows brown-black pigmentation.

Rotor syndrome is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder manifesting as mild conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. The primary defect appears to be a deficiency in the intra cellular storage capacity of the liver for binding anions. The liver histology is normal.

ACUTE VIRAL HEPATITIS

Viruses can affect the liver, either primarily, e.g. hepatitis A, B, C, E or as part of a systemic involvement, e.g. cytomegalo-virus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus(EBV), herpes simplex virus (HSV). In Indian children, hepatitis A is the commonest cause (40-60%) of acute viral hepatitis, followed by hepatitis E (10-20%) and hepatitis B (7-17%). Nearly 8-20% patients have coinfection with more than one virus, HAV and HEV being thecommonest. Hepatitis A and E are transmitted by feco-oral route whereas HBV and HCV are transmittedby parenteral or vertical(mother to baby) route (Table 11.24) (see also Chapter 10).

Clin ical Features

Following exposure, patients show a prodrome charac terized by low grade fever, malaise, anorexia and vomiting, followed by appearance of jaundice. Exami nation shows icterus, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly (small, soft in 15-20%). Mild ascites may be present in 10-15% cases, which resolves completely on followup. Over the next few weeks, the appetite improves, jaundice resolves and the child gets better. In young children asymptomatic and anicteric presentation of hepatitis A infection can occur.

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

|

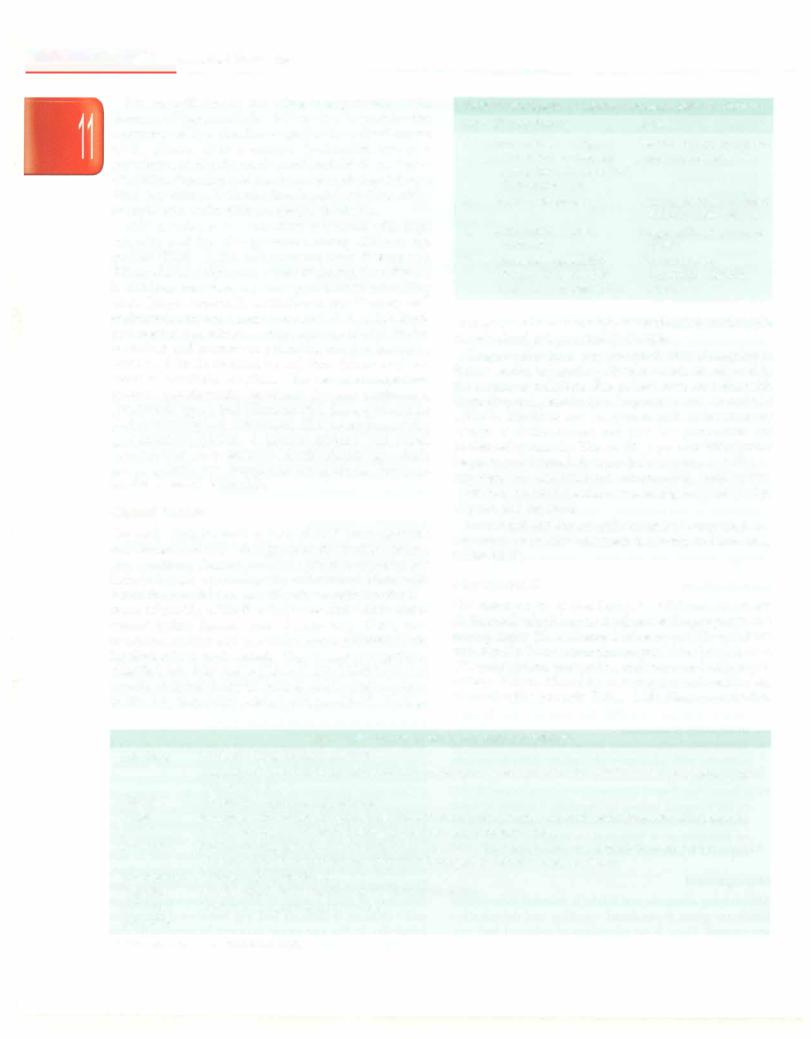

Table 11.24: Epidemiological profile of different hepatitis viruses |

|

||

Virus |

A |

B |

C |

E |

Type of virus |

RNA |

DNA |

RNA |

RNA |

Incubation period, days |

15-40 |

50-150 |

30-150 |

15-45 |

Route of infection |

|

|

|

|

Feco-oral |

+ |

|

|

+ |

Parenteral or others |

Rare |

Usually perinatal, |

Usually perinatal, |

|

|

|

by sexual contact |

by sexual contact |

|

Chronic liver disease |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vaccine |

Available |

Available |

No |

No (being developed) |

Diagnostic test |

IgM; anti-HAV |

HBsAg; IgM anti-HBc |

Anti-HCV antibody; |

IgM anti-HEV |

|

|

|

HCVRNA |

|

Differential Diagnosis

The conditions, which mimic the clinical features of viral hepatitis include enteric fever, falciparum malaria, leptospirosis and viral hemorrhagic fever. Other conditions that need to be differentiated include drug inducedhepatitis, acute presentation ofautoimmune liver disease or Wilson disease.

Investigations

Direct hyperbilirubinemia with markedly elevated ALT/ AST and normalalbumin andprothrombin time are usual. Mild leukopenia with relative lymphocytosis is seen. Ultrasound is not routinely required, but shows mildly enlarged liver with increased echogenicity and edema of gallbladder wall. Viral serologies help determine the etiology of acute viral hepatitis, as shown in Table 11.24.

Complications

These include:

1.Acute liverfailure. The appearanceofirritability,altered sleep pattern, persistent anorexia and uncorrectable coagulopathy (despite administration of vitamin K)

suggests the development of acute liver failure.

ii.Aplastic anemia

iii.Pancreatitis

iv.Serum sickness, vasculitis-like reaction may be seen in hepatitis B infection

v.Hemolysis (cola-colored urine) with renal failure in subjects with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

vi.Chronic liverdisease: In patients withviralhepatitis due to HBV, repeat testing for hepatitis B surface antigen should be done after 6 months to document clearance or persistence of infection. A majority (95%) clear hepatitis B infection after acute icteric infection.

Management

Maintaining adequate oral intake is essential intravenous fluids are given if persistent vomiting and dehydration are present. There is no advantage of enforced bed rest, but vigorous activity should be avoided. No specific

dietary modification is recommended. The child should be monitored for appearance of complications like encephalopathy.

Prevention

Public healthmeasureslikesanitation,safedrinkingwater supply, hand washing and proper food hygiene are of utmost importance, especially in epidemics of hepatitis A or E. Proper screening of blood and blood products and safe injection practices are essential. Universal immuni zation against hepatitis B is the most effective way of preventing hepatitis B related disease.

Suggested Reading

Acharya SK, Madan K, Dattagupta S, Panda SK.Viral hepatitis in India. Nat Med J India 2006;19:203-17

Strassburg CP. Hyperbilirubinemia syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010;24:555-71

Yeung LT, Roberts EA. Current issues in the management of pediatric viral hepatitis. Liver Int 2010;30:5-18

LIVER FAILURE

Liver failure refers to a clinical state resulting from hepatocyte dysfunction or necrosis and not a specific disease etiology. It may occur de nova in normal children without any evidence of pre-existing liver disease where it is known as acute liver failure (ALF).

Acute liverfailure. An international normalized ratio 2:1.5 with hepatic encephalopathy or an international norma lized ratio 2:2 without hepatic encephalopathy along with biochemical evidence of liver injury in the absence of underlying chronic liver disease is considered as acute liver failure. The presence of hepatic encephalopathy is not essential for diagnosis of ALF in children. All international normalized prothrombinvalues referto that measuredafter8 hr of parenteralvitamin K administration. This definition has evolved with the understanding that detection of mild grades of hepatic encephalopathy in small children is difficult and any behavioral change or irritability in this age group may not be necessarily due to hepatic encephalopathy.

___E_s_s_e_n_ tia_l_P_e_d_ i_a trics_________________________________

Patients with chronic liver disease may manifest with features of hepatocellular failure due to progressive worsening of liver function as part of the natural course of the disease or as a sudden dysfunction due to a superimposed hepatic insult resulting in acute on chronic liverfailure. Superimposedinsultcanbedueto hepatotropic virus (hepatitis A, E, B) infection, hepatotoxic drug intake or sepsis and varies with the geographical area.

ALF in children is a condition associated with high mortality and the etiology varies among different age groups (Table 11.25). Autoimmune liver disease and Wilson disease, important causes of chronic liver disease in children, may have an acute presentation mimicking ALF. Drugs, especially antituberculosis therapy and anticonvulsants are a major cause of ALF. In the West, paracetamol poisoning is a common cause of ALF. Herbal medicines and mushroom poisoning are also known to cause ALF. In the neonatal period, liver failure may be a result of metabolic conditions like neonatal hemochro matosis, galactosemia, hereditary fructose intolerance, tyrosinemia type 1 and Niemann-Pick disease, infections and hematological conditions like hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. A careful history and rapid investigations are necessaryto identifythe etiology, which has prognostic and therapeutic implications. However, 30--40% cases are idiopathic.

Clinical Features

The early clinical manifestations of ALF are nonspecific and characterized by lethargy, anorexia, malaise, nausea and vomiting. Central nervous system manifestations include hepatic encephalopathy andcerebraledema with raised intracranial tension. Hepatic encephalopathy is a result of inability of the liver to process and excrete endo genous toxins. Raised levels of ammonia, GABA, false neurotransmitters and pro-inflammatory cytokines are implicated in its pathogenesis. Hepatic encephalopathy is classified into four stages (Table 11.26). Identification of hepatic encephalopathy in children can be challenging as in the early stages they present with nonspecific findings

Table 11.26: Stages of hepatic encephalopathy in children

Stage Clinical features Reflexes

I |

Inconsolable crying, |

Normal or hyper-reflexic; |

|

inattention to task, not |

asterixis absent |

|

acting like self, disturbed |

|

|

sleep-wake cycle |

|

II |

Same as in stage I |

Normal or hyper-reflexic; |

|

|

asterixis easily elicited |

III |

Somnolence, stupor, |

Hyper-reflexic; asterixis |

|

combative |

present |

IV |

Comatose, responsive |

Decerebrate or |

|

to pain (IVA) or non |

decorticate; asterixis |

|

responsive to pain (IVB) |

absent |

suchasexcessivesomnolence, reversal ofsleep-wakecycle or behavioral and personality changes.

Coagulopathyduetoimpairedproductionofcoagulation factors results in bleeding. Platelet counts are affected in the setting of infection. The patient may manifest with hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalance and metabolic acidosis. Infections are common in ALF as the immune system is dysfunctional and invasive procedures are performedcommonly.Thisresultsin gram-positive, gram negative and fungal infections. Infection may manifest as hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation, worsening metabolicacidosis, worsening encephalopathy, oliguria and azotemia.

Investigations for specific causes if suspected are important as specific treatment is needed in these cases (Table 11.27).

Management

The management of liver failure in children is based on:

(i) diagnosis of etiology as it influences the prognosis and management; (ii) assessment of severity of liver failure and timely liver transplantation if indicated; and (iii) anticipation, prevention and treatment of compli cations. Patients should be treated and monitored closely in an intensive care unit (Table 11.28). Elective intubation

|

Table 11.25: Causes of acute liver failure in children |

Infections |

Common: Viral hepatitis (A, B, E) |

|

Uncommon:Adenovirus, Epstein-Barr,parvovirus,cytomegalovirus,echovirus,varicella,dengue,herpes simplex |

|

virus I and II* |

Others |

Septicemia*, malaria, leptospirosis |

Drugs |

Isoniazid with rifampicin, pyrazinamide, acetaminophen, sodium valproate, carbamazepine, ketoconazole |

Toxins |

Herbal medicines, Amanita pha/loides poisoning, carbon tetrachloride |

Metabolic |

Wilson disease, galactosemia*, tyrosinemia*, hereditary fructose intolerance*, hemochromatosis*, Niemann-Pick |

|

disease type C*, mitochondrial cytopathies*, congenital disorder of glycosylation |

Autoimmune |

Autoimmune liver disease |

Vascular |

Acute Budd-Chiari syndrome, acute circulatory failure |

Infiltrative |

Leukemia, lymphoma, histiocytosis* |

Idiopathic |

|

* More common in neonates and infants