Ghai Essential Pediatrics8th

.pdf

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

|

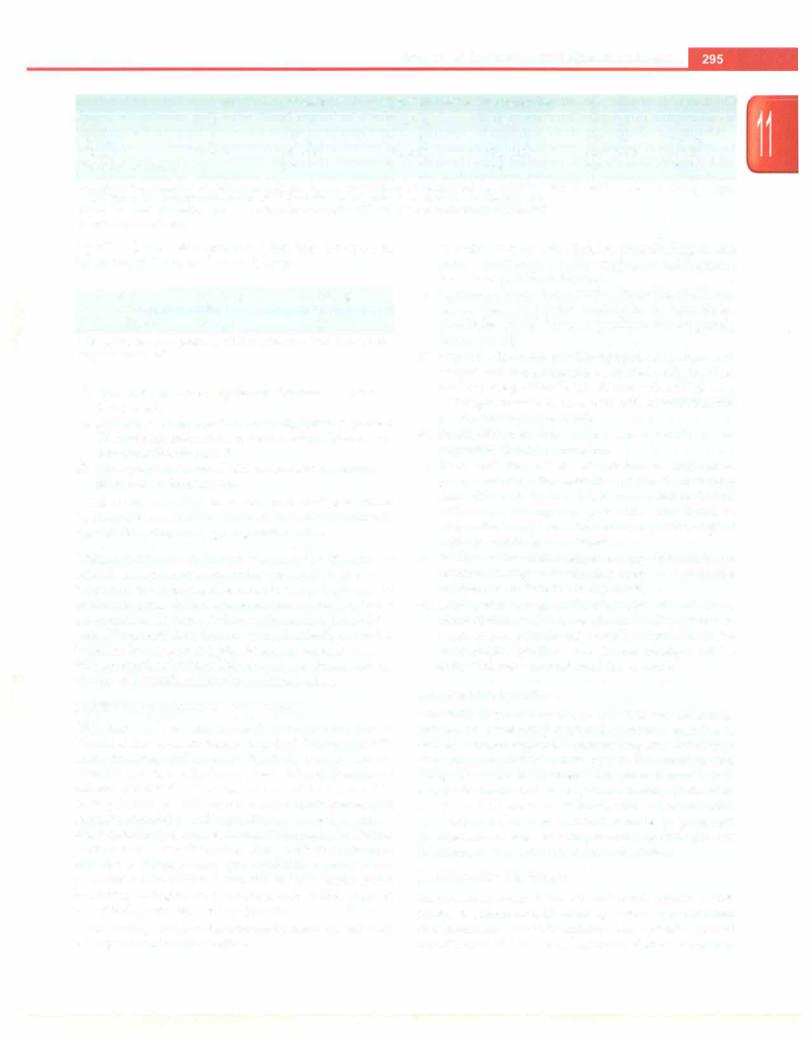

Table 11.12: Guidelines for treating patients with some dehydration (Plan B) |

|

||||

Age |

<41110 |

4-11 mo |

12-23 mo |

2-4 yr |

5-14yr |

?.15 yr |

Weight |

< 5 kg |

5-8 kg |

8-11 kg |

11-16 kg |

16-20 kg |

>30 kg |

ORS, ml |

200-400 |

400-600 |

600-800 |

800-1200 |

1200-2200 |

>2200 |

Number of glasses |

1-2 |

2-3 |

3-4 |

4-6 |

6-11 |

12-20 |

The approximate amount of ORS required (in ml) can also be calculated by multiplying the patient's weight (in kg) times 75. When body weight is not known, the approximate amount of ORS solution to give in the first 4 hr is given according to age

For infants under-6 months who are not breastfed, also give 100-200 ml clean water during this period Encourage breastfeeding

kg of IV fluid. Management following intravenous hydration end is to be done as follows:

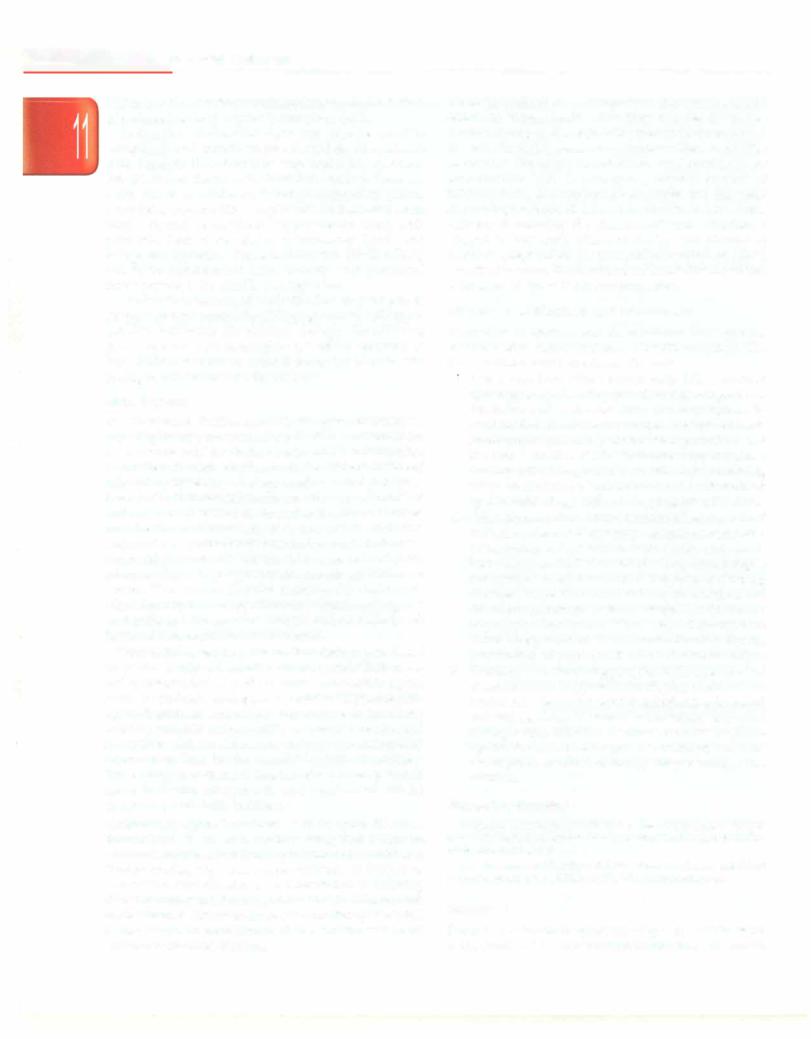

Age |

30ml/kg |

70ml/kg |

<12mo |

1 hr* |

5 hr |

>12mo |

30min* |

21h hr |

*The above can be repeated if child continues to have feeble/non palpable radial pulse

i.Persistence of severe dehydration. Intravenous infusion is repeated.

ii.Hydration is improved but some dehydration is present.

IV fluids are discontinued; ORS is administered over 4 hr according to Plan B

iii.There is nodehydration. IV fluids are discontinued; treat ment Plan A is followed.

The child should be observed for at least 6 hr before discharge, to confirm that the mother is able to maintain the child's hydration by giving ORS solution.

Unique problems in infants below 2 months of age

Breastfeedingmustcontinueduringthe rehydrationprocess, whenever the infant is able to suck. Complications like septicemia, paralytic ileus and severe electrolyte disturbance are more likely in young infants with diarrhea than at later ages. Diarrhea in these infants should be ideally treated as inpatient by experienced physicians at treatment centers withappropriatefacilities.Thisallowsforcareful assessment of need of systemic antibiotics and monitoring.

Nutritional Management of Diarrhea

Children with severe malnutrition (marasmus or kwashiorkor) are at an increased risk of developing both acute diarrhea and its complications, such as severe systemic infection, dehydration, heart failure, vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Feeding should not be restricted in such patients as this aggravates complications and increases morbidity and mortality. Early feeding during diarrhea not only decreases the stool volume by facilitating sodium and water absorption along with the nutrients, but also facilitates early gut epithelial recovery and prevents malnutrition. Once the child's status starts improving, a higher than recommended intake is given to facilitate complete catchup growth.

Following are the recommendations on dietary management of acute diarrhea:

i.In exclusively breastfed infants, breastfeeding should continue as it helps in better weight gain and decreases the risk of persistent diarrhea.

ii.Optimally energy dense foods with the least bulk, rec ommended for routine feeding in the household, should be offered in small quantities but frequently (every 2-3 hr).

iii.Staple foods do not provide optimal calories per unit weight and these should be enriched with fat or oil and sugar, e.g. khichri with oil, rice with milk or curd and sugar, mashed banana with milk or curd, mashed potatoes with oil and lentil.

iv.Foods with high fiber content, e.g. coarse fruits and vegetables should be avoided.

v.In nonbreastfed infants, cow or buffalo milk can be given undiluted after correction of dehydration toge ther with semisolid foods. Milk should not be diluted with water during any phase of acute diarrhea. Alternatively, milk cereal mixtures, e.g. dalia, sago or milk-rice mixture, are preferable.

vi.Routine lactose-free feeding, e.g. soy formula is not required during acute diarrhea even when reducing substances are detected in the stools.

vii.During recovery, an intake of at least 125% of recom mended dietary allowances should be attempted with nutrient dense foods; this should continue until the child reaches preillness weight and ideally until the child achieves a normal nutritional status.

Zinc Supplementation

Zinc deficiency has been found to be widespread among children in developing countries. Intestinal zinc losses during diarrhea aggravate pre-existing zinc deficiency. Zinc supplementation is now part of the standard care along with ORS in children with acute diarrhea. It is helpful in decreasing severity and duration of diarrhea and also risk of persistent diarrhea. Zinc is recommended to be supplemented as sulphate, acetate or gluconate formulation, at a dose of 20 mg of elemental zinc per day for children >6 months for a period of 14 days.

Symptomatic Treatment

An occasional vomit in a child with acute diarrhea does not need antiemetics. If vomiting is severe or recurrent and interferes with ORS intake, then a single dose of ondansetron (0.1-0.2 mg/kg/dose) should be given.

n i |

i |

is |

________________________ |

_____ |

__E_s e_s |

at_l_P_adetr |

c |

_ |

|

|

Children with refractory vomiting despite administration of ondansetron may require intravenous fluids.

Abdominal distension does not require specific treatment bowel sounds are present and the distension is mild. Paralytic ileus should be suspected if bowel sounds are absent and abdomen is distended. Paralytic ileus can occur due to hypokalemia, intake of antimotility agents, necrotizing enterocolitis or septicemia. In these cases, oral intake should be withheld. Hypokalemia along with paralytic ileus necessitates intravenous fluids and nasogastric aspiration. Potassium chloride (30-40 mEq/1) should be administered intravenously with parenteral fluids provided the child is passing urine.

Convulsions associated with diarrhea may be due to

(i) hypoorhypematremia; (ii)hypoglycemia; (iii)hypo kalemia following bicarbonate therapy for acidosis; (iv) encephalitis; (v) meningitis; (vi) febrile seizures; or (vii)cerebral venous or sagittal sinus thrombosis. The management depends on the etiology.

Drug Therapy

Mostepisodesofdiarrheaareself-limitinganddonotrequire any drug therapy except in a few situations. Antibiotics are not recommended for routine treatment of acute diarrhea in children. In acute diarrhea antimicrobial are indicated in bacillary dysentery, cholera, amebiasis and giardiasis. Escherichiacoliarenormalgutfloraandtheirgrowthonstool culture is not an indication for antibiotics. Acute diarrhea may be the manifestation of systemic infection and malnourished, prematurely bornandyoung infantsareat ahighrisk. Thus suchbabiesshouldbescreenedandgiven adequate days of age appropriate systemic antibiotics for sepsis. Presence of (i) poor sucking; (ii) abdominal distension; (iii) feverorhypothermia; (iv)fastbreathing;and

(v)significant lethargy orinactivityinwell-nourished,well hydrated infants points towards sepsis.

There islittlescientific evidence that bindingagentsbased on pectin, kaolin or bismuth salts are useful. Their use is not recommended in acute diarrhea. Antimotility agents such as synthetic analogues of opiates (diphenoxylate hydrochloride or lomotil and loperamide or imodium) reduce peristalsis or gut motility and should not be used in children with acutediarrhea. Reduction of gut motility allows more time for the harmful bacteria to multiply. These drugs may cause distension of abdomen, paralytic ileus, bacterial overgrowth and sepsis and can be dangerous, even fatal, in infants.

Antisecretory agents have been used in acute diarrhea. Racecadotril is an antisecretory drug that exerts its antidiarrheal effects byinhibiting intestinal enkephalinase. Recent studies reported some evidence in favour of racecadotril over placebo or no intervention in reducing the stool output and duration of diarrhea in children with acute diarrhea. However, more data on efficacy is needed before it can be recommended for routine use in all children with acute diarrhea.

Probiotics, defined as microorganisms that exert beneficial effects on human health when they colonize the bowel, have beenproposedas adjunctive therapyin the treatment of acute diarrhea. Severalmicroorganismslike Lactobacillus rhamnosus (formerly Lactobacillus casei strain GG or Lactobacillus GG), L. plantarum, several strains of bifidobacteria, Enterococcus Jaecium SF68 and the yeast Saccharomyces boulardii have been shown to have some efficacy in reducing the duration of acute diarrhea if started in very early phase of illness. The efficacy of probiotic preparations is strain and concentration (dose) specific. However, the routine use of probiotics in patients with acute diarrhea is not recommended.

Prevent ionof D iarrhea andMalnutr ition

Prevention of diarrhea and its nutritional consequences should receive major emphasis in health education. The three main measures to achieve this are:

1.Proper nutrition. Since breast milk offers distinct advantages in promoting growth anddevelopment of the infant and protection from diarrheal illness, its continuationshould be encouraged. Exclusive breast feedingmaynotbeadequateto sustain growthbeyond the first 6 months of life. Therefore, supplementary feeding with energy-rich food mixtures containing adequate amounts of nutrients should be introduced by 6 months of age without stopping breastfeeding.

ii.Adequate sanitation. Improvement of environment sanitation, clean water supply, adequate sewage dis posal system and protection of food from exposure to bacterialcontaminationareeffectivelongtermstrategies for control of all infectious illnesses including diarrhea. Three 'Cs; clean hands, clean container and cleanenvironmentarethekeymessages. Mothershould beproperlyeducatedabout this. Complementaryfoods should be protected from contamination during preparation, storage, or atthe time of administration.

iii.Vaccination. Evidencesuggests that with improvement in sanitation and hygiene in developing countries, the burdenof bacterialand parasitic infectionhas decreased andviral agentshave assumed anincreasinglyimportant etiologic role. Effective vaccines are now available against the commonest agent, i.e. rotavirus and their use might be an effective strategy for preventing acute diarrhea.

Suggested Reading

Bhatnagar S, Lodha R, Choudhury P, Sachdev HPS, ShahN, Narayan S et al. lAP Guidelines 2006 on Management of Acute Diarrhea. Indian Paediatrics 2007; 44:380

The Treatment of Diarrhea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. WHO (2005). WHO/CDD/SER/80.2

Dysentery

Dysentery refers to the presence of grossly visible blood in the stools and is a consequence of infection of the colon

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

by either bacteria or ameba. Bacillary dysentery is much more common in children than amebic dysentery. The bacteria causing bloody diarrhea are Shigella species

(5. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii and S. sonnei.), enteroinvasive and enterohemorrhagic E. coli, Salmonella and Campylobacter jejuni. S. flexneri is the commonest organism reported in developing countries and S. dysenteriae is associated with epidemics of dysentery.

Achildwithbacillary dysenterypresentswith fever and diarrhea. Diarrhea may be watery to start with, but then shows mucus and blood mixed with stools. There is tenesmus,whichrefers to ineffectualdefecation alongwith straining and suprapubic discomfort. The illness may be complicatedbydehydration,dyselectrolytemia,hemolytic uremic syndrome, convulsions, toxic megacolon, intestinal perforation, rectal prolapse and, very rarely, Shigella encephalopathy.

Administration of ORS, continuation of oral diet, zinc supplementation and antibiotics are the components of treatment. Stool culture and sensitivity should be sent for before startingempiricalantibiotics.Antimicrobialagents arethemainstayoftherapyofallcasesofshigellosis. Based on safety, low cost and efficacy, ciprofloxacin (15 mg/kg/ dayintwodivideddosesfor3days)hasbeenrecommended byWorld Health Organization (WHO) asthefirst line anti biotic for shigellosis. However, antimicrobial resistance to fluoroquinolones had increased significantly from 2002to 2011 and only ceftriaxone has been shown to be uniformly effective.Keepingthisinmind,intravenousceftriaxone (50100 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days) should be the first line of treatment in a sick child. In a stable child, either ciproflo xacinor oral cefixime may begiven, but the patientshould bemonitoredforclinicalimprovementwithin48hr(decrease in fever, stool frequencyand blood instools). Ifnoimprove ment is seen at 48 hr, antibiotics should be changed appropriately.Oralazithromycin(10 mg/kg/dayfor3days) can be used for shigellosis but the experience is limited.

Amebic dysentery is less common among children. The onset is insidious. Tinidazole or metronidazole is the drug of choice. Any young child presenting with blood in stools and persistent abdominal pain should be suspected to have intussusception and evaluated accordingly.

PERSISTENT DIARRHEA

Persistent diarrhea is an episode of diarrhea, of presumed infectious etiology, which starts acutely but lasts for more than 14 days. It should not be confused with chronic diarrhea which has a prolonged duration but an insidious onset and includes conditions causing malabsorption.

1.Thepredominantproblemis the worsening nutritional status that, in tum, impairs the reparative process in the gut. This worsens nutrient absorption and initiates a vicious cycle that can only be broken by proper nutrition. Persistent diarrhea is more common in malnourished children. Apart from malabsorption, malnutritionalsoresultsfrominadequatecalorie intake due to anorexia, faulty feeding and improper counse ling regarding feeding by doctors. One of the major obstacles to nutritional recovery is secondary lactose intolerance, and in some cases, impaired digestion of other complex carbohydrates due to decrease in brush border disaccharidases.

ii.Pathogenic E. coli, especially the enteroaggregative and enteroadherent types, result in malabsorption by causing persistent infection.

iii.Associated infections of the urinary tract or another focus of infection (more commonly in malnourished children) contribute to failure to thrive and mortality.

iv.Prolongation of an acute diarrhea may rarely be a manifestation of cow milk protein allergy. The increased gut permeability in diarrhea predisposes to sensitization to oral food antigens.

v.The use of antibiotics in acute diarrhea suppresses normal gut flora. This may result in bacterial over growth with pathogenic bacteria and/or overgrowth of fungi, resulting in persistent diarrhea and malabsorption

vi.Cryptosporidium infection is frequently implicated in persistentdiarrhea,eveninimmunocompetentchildren

Clinical Features

Majority of patients with persistent diarrhea pass several loose stools daily but remain well hydrated. Dehydration develops only in somepatients due to high stool output or when oral intake is reduced due to associated systemic infections. The major consequences of persistent diarrhea are growth faltering, worsening malnutrition and death due to diarrheal or nondiarrheal illness. The presence of secondary lactose intolerance shouldbe considered when thestoolsareexplosive (i.e. mixedwithgasandpassedwith noise) andinpresenceofperianal excoriation. ThestoolpH is low and stool test for reducing substances is positive. Unabsorbed dietary lactose once delivered to colon is converted to hydrogen and lactic acid by colonic bacteria. Lactic acid results in decreased stool pH, explosive stools areduetohydrogenandunabsorbedlactosegivespositive reducing substances, if tested. There is no need for laboratory testing for stool pH and reducing substances when the history is classical and excoriation is marked.

Etiopathogenesis

Although persistent diarrhea starts as acute infectious diarrhea, the prolongation of diarrhea is not entirely due to infection. Various factors that are implicated in pathogenesis include.

Management

The principles of management are: (i) correction of dehydration, electrolytes and hypoglycemia; (ii) evaluation forinfectionsusingappropriateinvestigations (hemogram, blood culture and urine culture) and their management;

- Essential Pediatrics

and (iii) nutritional therapy. Two-thirds of patients with persistent diarrhea can be treated on outpatient basis. Patients in need of hospital admission are those with

(i) age less than 4 months and not breastfed; (ii) presence of dehydration; (iii) severe malnutrition (weight for height <3 SD, mid-upper arm circumference <11.5 cm for children at 6-60 months of age, or bilateral pedal edema); or (iv) presence or suspicion of systemic infection.

Nutrition

Feeding should be started at the earliest. Initially 6-7 feeds are given everyday and a total daily caloric intake of 100 kcal/kg/day is ensured. Caloric intake should be increa sed gradually over 1-2 weeks to 150 kcal/kg/day in order to achieve weight gain. Tube (nasogastric) feeding may be done initially in children with poor appetite due to presence of serious infection. To ensure absorption and decrease stool output, one may attempt to overcome varying degrees of carbohydrate maldigestion by using diets with different degrees of carbohydrate exclusion in the form of diet A (lactose reduced), diet B (lactose free) and diet C (complex carbohydrate free) diets (Table 11.13).

Initial diet A (reduced lactose diet; milk rice gruel, milk sooji gruel, rice with curds, dalia) This is based on

thefactthat secondary lactose intolerance exists in children with persistent diarrhea and malnutrition. Clinical trials have shown that reduced lactose diet is tolerated equally well as totally lactose-free diet, without significantly increasing stool output or risk of dehydration. If the patient is fed entirely on animal milk, the quantity should be reduced to 50-60 ml/kg providing not more than 2 g of lactose/kg/day. To reduce lactose concentration in animal milk, it should be mixed with cereals, but not diluted with water as that reduces the caloric content. Milk cereal mixtures, e.g. milk or curd mixed rice gruel, milk

sooji gruel, or dalia are palatable, provide good quality proteins and some micronutrients and result in faster weight gain than milk-free diets.

Second diet B (lactose-free diet with reduced

starch) About 65-70% of children improve on the initial diet A. The remainder have impaired digestion of starch and disaccharides other than lactose. These children, if free of systemic infection, are advised diet B which is free of milk (lactose) and provides carbohydrates as a mixture of cereals and glucose. Milk protein is replaced by chicken, egg or protein hydrolysate. The starch content is reduced and partiallysubstituted by glucose. Substituting only part of the cereal with glucose increases the digestibility but at the same time does not cause a very high osmolarity.

Third diet C (monosaccharide-based diet) Overall,

80-85% of patients with severe persistent diarrhea will recover with sustained weight gain on the initial diet A or the second diet B. A small percentage may not tolerate a moderate intake of the cereal in diet B. These children are given diet C which contains only glucose and a protein source as egg white or chicken or commercially available protein hydrolysates. Energy density is increased by adding oil to the diet.

Thestrategy of carbohydrateexclusionto varying degrees in plan A, B and C diets are meant to circumvent the problem of carbohydrate malabsorption. In addition green (unripe) banana diet is gaining acceptance for treatment of persistent diarrhea. Fermentation of nondigestible soluble fibers in cooked green (unripe) banana by colonic bacteria generates short chain fatty acids which are absorbed along with sodium, thereby conserving dietary nutrients.

Indications for change from the initial diet (diet A) to the next diet (diet B or diet C) The diet should be

changed to the next level if the child shows (i) marked

|

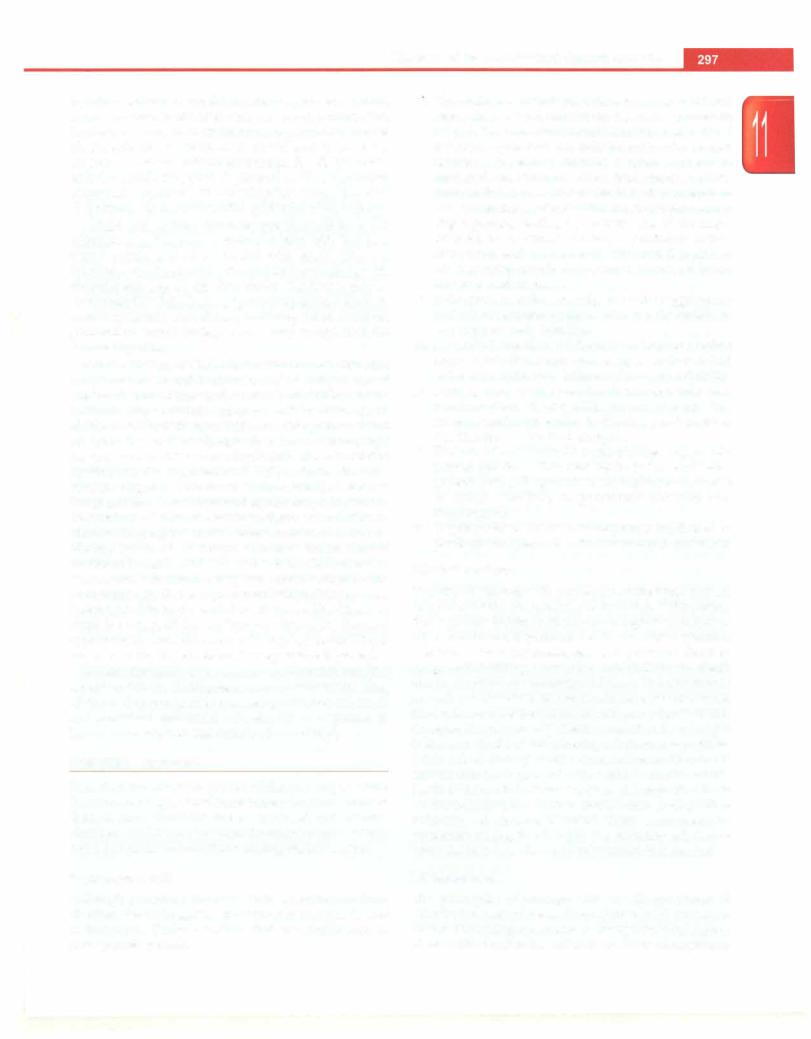

Table 11.13: Diets for persistent diarrhea |

|

Diet A (reduced lactose) |

Diet B (lactosefree) |

Diet C (monosaccharide based) |

Constituents |

|

|

Milk (1/3 katori/50 ml) |

Egg white (3 tsp/half egg white) |

Chicken puree (5 tsp/15 g) or |

Puffed rice powder/cooked rice or |

Puffed rice powder/cooked rice |

egg white (3 tsp/half egg white) |

sooji (2 tsp/6 g) |

(3 tsp/9 g) |

|

Sugar (Ph tsp/7 g) |

Glucose (Ph tsp/7 g) |

Glucose (Ph tsp/7 g) |

Oil (1 tspI4.5 g) |

Oil (Ph tsp/7 g) |

Oil (Ph tsp/7 g) |

Water (2/3 katori/100 ml) |

Water (3/4 katori/120 ml) |

Water (1 katori/150 ml) |

Preparation

Mix milk, sugar and rice, add boiled water and mix well, add oil.

Nutrient content

After whipping the egg white, add rice, glucose and oil and mix well. Add boiled water and mix rapidly to avoid clumping

Boil chicken and make puree after removing bones. Mix it with glucose and oil. Add boiled water to make a smooth flowing feed

85 kcal and 2.0 g protein |

90 kcal and 2.4 g protein |

67 kcal and 3.0 g protein per 100 g |

per 100 g |

per 100 g |

|

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

increase in stool frequency (usually more than 10 watery stools/day) at any time after at least 48 hr of initiating the diet; (ii) features of dehydration any time after initiating treatment; or (iii) failure to gain weight gain by day 7 in the absence of initial or hospital acquired systemic infection. Unless signs of treatment failure occur earlier, each diet should be given for a minimum period of 7 days.

Resumption of regular diet after discharge. Children dischar ged on totally milk free diet should be given small quan tities of milk as part of a mixed diet after 10 days. If they tolerate this and have no signs of lactose intolerance (abdominal pain, abdominal distension and excessive flatulence) then milk can be gradually increased over the next few days. Age appropriate normal diet can then be resumed over the next few week.

Supplement vitamins and minerals Supplemental multivitamins and minerals, at about twice the RDA, should be given daily to all children for at least 2-4 weeks. Iron supplements should be introduced only after the diarrhea has ceased. Vitamin A (as a single dose) and zinc are supplemented as both of them enhance the recovery from persistent diarrhea. A single oral dose of vitamin A should be given routinely, at 2,00,000 IU for children>12 months or 100,000 IU for children 6-12 months. Children weighing less than 8 kg, irrespective of their age, should be given 1,00,000 IU of vitamin A. One should administer 10-20 mg per day of elemental zinc for at least 2 weeks to children between 6 months and 3 yr of age.

Additional supplements for severely malnourished infants and children Magnesium and potassium

supplementation isprovided to these children. Magnesium is given by intramuscular route at 0.2 ml/kg/dose of 50% magnesium sulphate twice a day for 2-3 days. Potassium is supplemented at 5-6 mEq/kg/day orally or as part of intravenousinfusion during the initial stabilization period. Role of antibiotics The indiscriminate use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute diarrhea is among the reasons for persistent diarrhea. Hence, the use of empirical antibiotics atadmissionistobeindividualizedandreservedforchildren with either of the following features: (i) severe malnutrition (majority of these children have associated systemic infections and clinical signsofinfection maynotbe obvious); and (ii) evidence of systemic infection. A combination of cephalosporin and aminoglycoside can be started empiri callyandthereafterchangedaccording to reportsof culture/ sensitivity. Urinary tract infection is common (seen in 1015%) and should be treated appropriately.

Monitoring Response to Treatment

Successful treatment is characterized by adequate food intake, reduced frequency of diarrheal stools (<2 liquid stools/day for 2 consecutive days) and weight gain. Most children will lose weight in the initial 1-2 days and then show steady weight gain as associated infections are

treated and diarrhea subsides. All children should be followed regularly even after discharge to ensure continued weight gain and compliance with feeding advice.

Prognosis

Most patients with persistent diarrhea recover with an approach of stepped up dietarymanagement as discussed above. A small subgroup (<5%) may be refractory and require parenteral nutrition and extensive workup. These patients generally have high purge rate, continue to lose weight, do not tolerate oral feeds and require referral to specialized pediatric gastroenterology centers.

CHRONIC DIARRHEA

Chronic diarrhea is a common problem in children. It is defined as an insidiousonsetdiarrhea of>2weeksduration inchildrenand>4weeksin adults. The termchronicdiarrhea is not synonymous with persistent diarrhea. The approach, etiology and management of chronic diarrhea along with a brief outline of some common causes is discussed.

Approach

Approach to chronic diarrhea must be considered with the following points in mind:

Age of onset. A list of common causes of chronic diarrhea according to age of onset is shown in Table 11.14.

Small or large bowel type of diarrhea. Features in history and examination that help in differentiating small bowel from large bowel diarrhea is shown in Table 11.15. Typically, large volume diarrhea without blood and mucus suggests small bowel type of diarrhea and small volume stools with blood and mucus suggest large bowel type of diarrhea.

Gastrointestinal versus systemic causes: Diarrhea is most commonly of intestinal origin and sometimes pancreatic, or rarely, hepatobiliary in etiology. Cholestasis due to biliaryobstructionorintrahepatic cause can cause diarrhea due to fat malabsorption. Pruritus and malabsorption of fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) and calcium are commonly associated. Maldigestion due to deficiency of pancreatic enzymes leads to pancreatic diarrhea in cystic fibrosis, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (cyclic neutropenia and bone abnormalities) or chronic pancreatitis. Other causes include Zollinger-Elison syndrome, and secretory tumors like VIPoma, carcinoid ormastocytosis.Diarrhea may also be a systemic manifestation of other conditions like sepsis or collagen vascular disorders.

Specific questions in history should include:

i.Duration of symptoms; nature, frequency and consis tency of stools; and presence of blood, mucus or vis ible oil in stools

11.Age of onset; relationship of dietary changes, e.g. introduction of milk or milk products and wheat or

|

E s s |

|

s |

|

|

______________ |

|

|

en t iai |

P ed iat ric |

|

_____________ |

_ |

||

|

__ |

_ _ _ |

_ _ _ _ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ ______ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

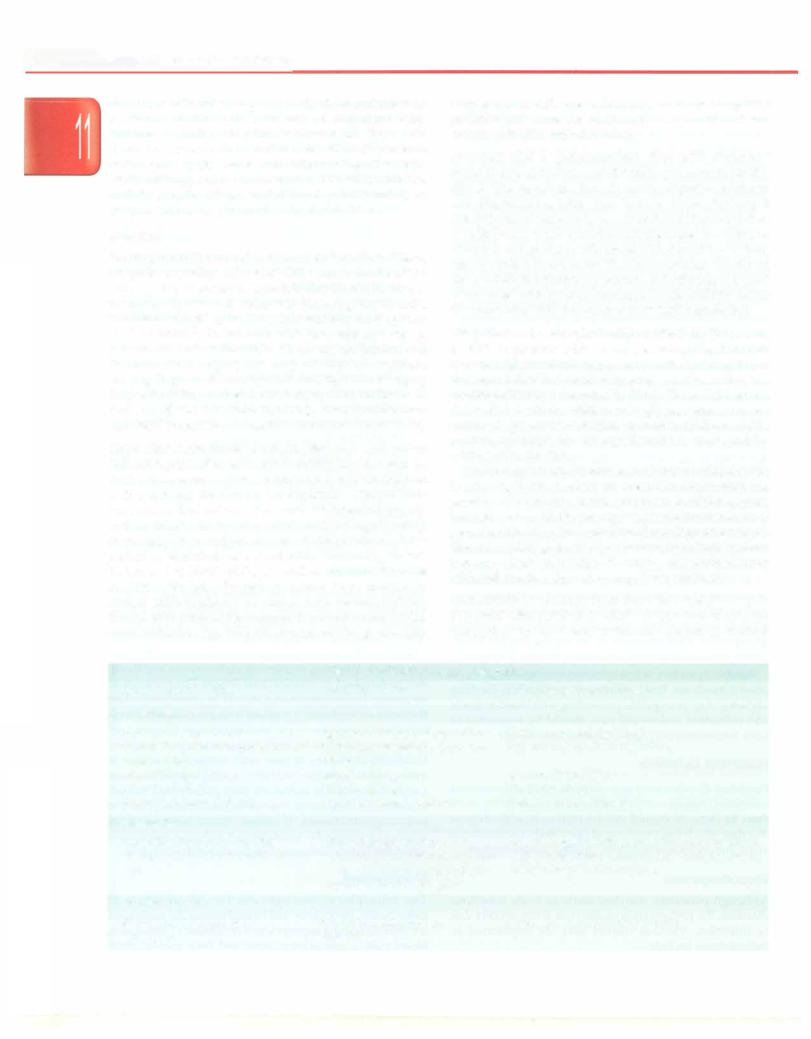

Table 11.14: Causes of chronic diarrhea according to age of onset (in order of importance) |

||||

|

Age <6 mo |

|

|

Age >6 mo to 5 yr |

Age >5 yr |

||

|

Cow milk protein allergy |

Cow milk protein allergy |

Celiac disease |

||||

|

Lymphangiectasia |

|

Celiac disease |

Giardiasis |

|||

|

Urinary tract infection* |

Giardiasis |

Gastrointestinal tuberculosis |

||||

|

Short bowel syndrome** |

Toddler diarrhea |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

||||

|

Immunodeficiency states |

Lymphangiectasia |

Immunodeficiency |

||||

|

Cystic fibrosis |

|

|

Short bowel syndrome** |

Bacterial overgrowth |

||

|

Anatomical defects |

|

Tuberculosis |

Lymphangiectasia |

|||

|

Intractable diarrheas of infancy*** |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

Tropical sprue |

||||

|

Microvillous inclusion disease |

Immunodeficiency |

Immunoproliferative small |

||||

|

Tufting enteropathy |

Bacterial overgrowth |

intestinal disease |

||||

|

Autoimmune enteropathy |

Pancreatic insufficiency |

Pancreatic insufficiency |

||||

|

Glucose galactose malabsorption |

|

|

|

|||

|

Congenital sodium/chloride diarrhea |

|

|

|

|||

Should be considered in young infants with chronic diarrhea, particularly if fever is noted

••Consider if there is antecedent history of small bowel surgery

•••These rare conditions should only be considered if the diarrhea is very early in its onset (neonate to 3 months) and common conditions have been ruled out

Table 11.15: Differentiating small bowel from large bowel diarrhea

Features |

Small bowel diarrhea |

Large bowel diarrhea |

Stool volume |

Large |

Small |

Blood in stool |

No |

Usually present |

Rectal symptoms, e.g. urgency, tenesmus |

No |

Yes |

Steatorrhea (greasy stools) |

Yes |

No |

Carbohydrate malabsorption |

Yes, explosive |

No |

Protein malabsorption |

Yes |

No |

Pain (if any) |

Periumbilical, no reduction after |

Hypogastric, reduced after |

|

passage of stool |

passage of stool |

Color of stool |

Pale |

Normal |

Smell of stool |

Unusually offensive |

Normal |

Nutrient deficiency |

Frequent |

Can occur due to blood loss |

wheat products, with onset of diarrhea; and any specific dietary preferences, like avoidance of juices

iii.Familyhistoryofatopy(foodallergy,asthmaorallergic rhinitis), celiac disease, Crohn disease orcystic fibrosis

iv.History of abdominal surgery, drug intake, systemic disease, features of intestinal obstruction, pedal edema, anasarca, recurrent infections at multiple sites, previous blood transfusion and coexisting medical problems which predispose the child to diarrhea (e.g. congenital immunodeficiency, diabetes mellitus, hy perthyroidism, cystic fibrosis)

Important components of physical examination include

i.Anthropometry

ii.Signs of dehydration

iii.Signs of vitamin or mineral deficiencies (e.g. conjunc tiva! xerosis, Bitot spots, angular stomatitis, glossi tis, cheilitis, rickets, phrynoderma)

iv.Edema, whether symmetric or asymmetric; pitting or non pitting (lymphedema)

v.Fever and signs of systemic sepsis

vi.Extragastrointestinal manifestations in eye, skin, joints, oral cavity (suggest inflammatory bowel dis ease, IBD)

vii. Inspection of perianal area for fissures, anal tags and fistulae (seen in IBD)

viii.Oral thrush and scars of recurrent skin infections (suggest immunodeficiency)

ix.Abdominal distention, localized or generalized ten- derness, masses, hepatosplenomegaly and ascited.

Approach basedon age ofonset Ininfants <6months, cow milk protein allergy and intestinal lymphangiectasia should be considered first. The important clues to each etiology is given inTable 11.16.

Inyoungchildren,celiacdiseaseisthemostcommoncause of chronic diarrhea in North India. Cow milk protein allergy usuallyresolvesby3-5 yr; hence, this diagnosis should not be considered in children with onset of diarrhea beyond 5 yr. Toddlerdiarrhea isadiagnosisofexclusionaftercommon causeshavebeenruledout.Theonsetofdiarrheaisbetween 6 months and 3 yr ofage. The childpasses 3-6 loose stools, mostly during waking hour. Diarrhea worsens with low residue,lowfatorhighcarbohydratediet. Thechildiswell thriving, there is no anemiaor vitamin deficiencies andthe diarrhea resolves spontaneously by about 4 yr of age. Treatment iswith dietary modification; a high (>40%) fat,

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

lowcarbohydrate diet (especially with decreasedintake of juices) and increase in dietary fiber is recommended. IBO is less common in this age group as compared to older children. Giardiasis canbe diagnosedif multiplefreshstool samples (at least 3 in number) are tested for trophozoites. The laboratory may be asked to use concentration methods. Presence of cysts of giardia in immunocompetent patients does not merit a therapy of giardiasis.

Limited etiologies cause chronic diarrhea in older children (Table 11.16). A brief description of common causes of chronic diarrhea is given below.

Celiac Disease

This is an enteropathy caused by permanent sensitivity to gluten in genetically susceptible subjects. It is the most common cause of chronic diarrhea in children over 2 yr of age in North India. High-risk groups include subjects with Type 1 diabetes mellitus, Down syndrome, selective IgA deficiency, autoimmune thyroid disease, Turner syndrome, Williams syndrome, autoimmuneliverdisease and first-degree relatives of celiac disease patients. These subjects are at an increased risk of developing celiac disease and thus should be screened.

Presentation The classical presentation is with small bowel diarrhea, growth failure and anemia. A temporal associationofdiarrheaandintroductionof wheat products at weaning may be present. Onset of diarrhea before introduction ofwheatproducts in diet negates a diagnosis of celiac disease. It may also present without chronic

Table 11.16: Diagnostic clues to important causes of chronic diarrhea

Cow milk |

Onset of diarrhea after introduction of |

protein allergy |

cow or buffalo milk or formula |

|

Rectal bleeding (due to colitis) |

|

Anemia; failure to thrive |

|

Family history of allergy or atopy |

|

Response to milk withdrawal |

Lymphangiectasia |

Nonpitting pedal edema suggesting |

|

lymphedema |

|

Recurrent anasarca |

|

Hypoalbuminemiaandhypoproteinemia |

|

Lymphopenia |

|

Hypocalcemia |

Cystic fibrosis |

History of meconium ileus |

|

Predominant or associated lower |

|

respiratory tract infections |

|

Severe failure to thrive |

|

Clubbing |

|

History of sibling deaths |

|

High sweat chloride (>60 mEq/1) |

Immuno- |

Predominant fever |

deficiencies |

Recurrentinfectionsinvolvingothersites |

|

History of sibling deaths |

|

Organomegaly |

|

Opportunistic infections on stool |

|

examination |

diarrhea asrefractory iron deficiency ordimorphic anemia not responding to oralsupplements,shortstature,delayed puberty, rickets and osteopenia. Examination reveals failure to thrive, loss of subcutaneous fat, clubbing, anemia, rickets and signs of other vitamin deficiencies.

A high index of suspicion for celiac disease is the key to diagnosis.

Diagnosis The main investigations required for making a diagnosis include:

i.Serology. IgAantibodyagainsttissuetransglutaminase (tTG) is an ELISA based test, recommended for initial testing of celiac disease. It has a high sensitivity (92-100%) and specificity (91-100%) in both children and adults. IgAantiendomysialantibody is an equally accurate test(sensitivity88-100%; specificity91-100%) but is more difficulttoperform.The diagnosis of celiac disease should not be based only on celiac serology as serology may be false positive, false negative and interlaboratory variations are also present.

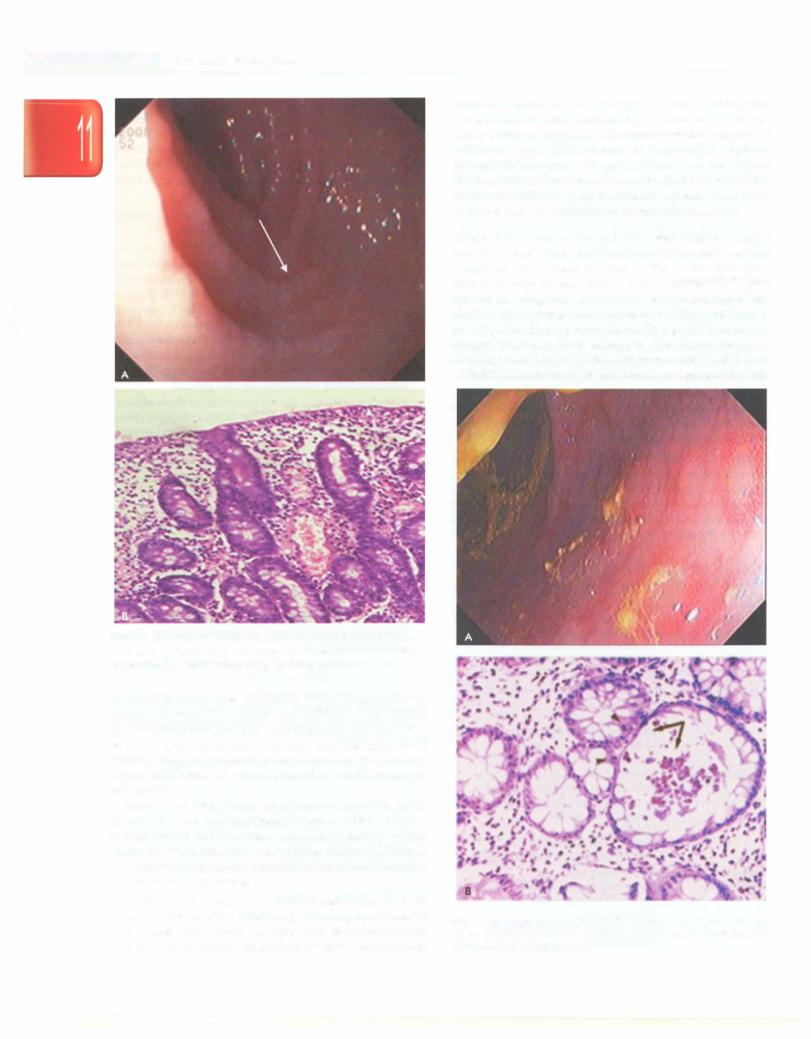

11.Upper GI endoscopy. It may be normal or show absence offolds orscallopedfolds (Fig.11.8A).Multiple (4-6in number)endoscopicbiopsiesfromthebulbandsecond/ third part of duodenum should be taken in all cases.

iii.Histology. The characteristic histological changes in celiacdiseaseareincreasedintraepitheliallymphocytes (>30/100 enterocytes), increased crypt length, partial to total villous atrophy, decreased villous to crypt ra tio and infiltration of plasma cells and lymphocytes in lamina propria (Fig. ll.8B).

Diagnosis of celiac disease (based on the modified criteria ofthe European Society of Pediatric Gastroentero logy, Hepatology and Nutrition, ESPGHAN) requires the following:

i.Clinical features compatible with diagnosis.

ii.Positive intestinal biopsy as described above with or without serology.

iii.Unequivocalresponseto glutenfree diet (GFD) within

12 weeks of initiation of GFD.

A positive serology makes the diagnosis more definite especially in developing countries where other causes of villousatrophyarecommondue to intercurrent infections or undernutrition.

Treatment The treatment involves life-long GFD and correction of iron, folate and other vitamin/mineral defi ciencies by supplementation. The patient should be assessed at 3 months for responseto GFD. After initiation of GFD, all symptoms should subside and weight and height gain should be present. Repeated explanation to patientandparentsbydoctorsisveryhelpfulinsustaining compliance after the child has become asymptomatic.

Cow Milk Protein Allergy

Cow milk protein allergy (CMPA) affects 2 to 5% of all children in the West, with the highest prevalence during the first year of life. In India, CMPA accounts for -13% of

|

E s s en t ial P ed iat rics |

__ |

__ |

_______ |

_______________________ |

|

|

__ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ |

|

|

||

|

|

|

||||

Figs 11.8A and B: Celiac disease. (A) Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing scalloping of duodenal folds (arrow);

(B) duodenal histology showing total villous atrophy

all malabsorption cases in children <2 yr of age. A family history of atopy is common in children with CMPA. Nearly50% childrenoutgrow theallergyby 1 yr and -95% by 5 yr of age. It is the most common food allergy in small children who are topfed but can also occur occasionally in breastfed babies due to passage of cow milk antigen in breast milk.

There are two kinds of reactions to cow milk:

(i) Immediate, i.e. IgE mediated: It occurs within minutes of milk intake and is characterized by vomiting, pallor, shock-like state, urticaria and swelling of lips. (ii) Delayed, i.e. T cell mediated: It has an indolent course and presents mainly with GI symptoms.

Symptoms The most common presentation is with diarrhea with blood and mucus. Depending upon the site and extent of involvement, the child may have small bowel, large bowel or mixed type diarrhea. In an Indian

study 40% children presented with bloody diarrhea, 33% watery and 7% with a mixed type of diarrhea. Uncom monly reflux symptoms and hematemesis may be present indicating upper GI involvement. Respiratory symptoms (allergic rhinitis and asthma) and atopic manifestations (eczema, angioedema) may be seen in 20-30% and 50-60% cases respectively. Iron deficiency anemia, hypopro teinemia and eosinophilia are commonly present.

Diagnosis In India non-IgE mediated CMPA is more common. Sigmoidoscopy (aphthous ulcers and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia as seen in Fig. 11.9A and rectal biopsy (plenty of eosinophils as seen in Fig. 11.9B give clue to the diagnosis in >95% cases irrespective of the clinical presentation and should be the first line of investigation in suspected cases. The gold standard for diagnosis of any food allergy is the elimination and challenge test. Typically the symptoms subside after milk withdrawal and recur within 48 hr of re-exposure to milk.

Figs 11.9A and B: Cow milk protein allergy. (A) Sigmoidoscopy showing aphthous ulcers; (B) rectal biopsy showing eosinophilic infiltration with crypt abscess

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver

Treatment All animal milk/milk products have to be removed from the diet. Soyor extensivelyhydrolyzedfor mula,bothof whichareequallyeffectiveintermsofgrowth and nutrient intake can be used as alternatives. Although soy ismorepalatable andcheap but itisnotrecommended in infants <6 months of age. Also 10-15% of CMPA have concomitant soy allergy, thus necessitating use of exten sively hydrolyzed formulae. A minority of children may nottolerate theextensivelyhydrolyzed formulaeandneed elemental amino acid formulas. Parental education regarding diet and calcium supplementation is essential.

Intestinal Lymphangiectasia

Itischaracterizedbyectasiaofthe bowellymphaticsystem, which on rupture causes leakage of lymph in the bowel. The disease is often associated with abnormal lymphatics in extremities. Signs and symptoms include peripheral edema which could be bilateral and pitting due to hypo albuminemia or asymmetrical and nonpitting due to lymphedematous limb. Diarrhea, abdominal distension and abdominal pain are commonly present. Abdominal and/or thoracic chylouseffusions may beassociated. Pre sence of hypoalbuminemia,low immunoglobulins, hypo calcemia and lymphopenia is characteristic of lymph angiectasia. Barium mealfollow-throughshows thickening of jejuna! folds with nodular lucencies in mucosa. On UGI endoscopy after fat loading with 2 gm/kg of butter at bedtime scattered white plaques or chyle like substance coveringthe mucosa may be seen (Fig. 11.lOA). Duodenal biopsy reveals dilated lacteals in villi and lamina propria (Fig. 11.lOB). The treatment consists of a low fat, high proteindietwithMCToil,calcium and fat soluble vitamin supplementation. Intravenous albumin is required for symptomatic management and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is reserved for management of chylous effusions. Resection may be considered if the lesion is localized to a small segment of intestine.

Immunodeficiency

Bothcongenitalandacquiredimmunodeficiency cancause chronic diarrhea. It should be suspected if there is history of recurrent infections at multiple sites (chest/GI/skin) and wasting. The common immunodeficiency conditions presenting with diarrhea include IgA deficiency, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). There is increased risk of celiac disease (10-20-fold increase) and Crohn disease in patients with IgA deficiency. Diarrhea is either due to enteric infections like giardia, cryptosporidium, CMV, etc. or due to bacterial overgrowth. Diagnosis is made by measuring serum immunoglobulins, Tcellcounts andfunctions, phagocytic function (nitro bluetetrazolium reduction test)depending upon the suspected etiology. Treatment involves administration of antimicrobialsfor bacterial overgrowth and opportunistic infections and therapy for underlying

Figs 11.1 OA and B: Intestinal lymphangiectasia. (A) Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing white deposits; (B) duodenal histology shows dilated lacteals

cause (IV immunoglobulins, y interferon or bone marrow transplantation).

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Chronic diarrhea is a common feature in children with AIDS. The impaired mucosal immunity results in recurrent oppor tunisticinfectionsand the alteredmaturationandfunction of enterocytes results in increased permeability and decreased functional absorptive surface with or without bacterial overgrowth. AIDS enteropathy is characterized by chronic diarrhea and marked weight loss in absence of enteric pathogens. The children are often sick with other clinical manifestations but sometimes diarrhea may be the only symptom. Presence of oral thrush, lymphadenopathy hepatosplenomegaly and parotiditis (10-20% cases) gives clue to the diagnosis. The common infections include:

1.Viral. Cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, adenovirus, norovirus

n |

l |

i |

__E_s_s_ e_ |

_t_ iaP_e _da t _r_ics__________________________________ |

|

|

||

ii.Bacterial. Salmonella, Shigella, Mycobacterium avium com plex (MAC), Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium difficile

m. Fungi. Candidiasis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis

iv.Protozoa. Microsporidium, Isospora belli, Cryptosporidium, Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Cyclospora,

Blastocystis hominis

Multiple stool examinations are required to identify the causative etiology by using special stains and PCR techniques. Colonic/terminalileumbiopsy and duodenal fluidexamination are the other ways of diagnosingoppor tunisticinfections.Treatmentiswithspecificantimicrobials along withHAART (highly active anti-retroviraltherapy).

Drug Induced Diarrhea

Diarrhea can be a side effect of many pharmacologic agents. Altered GI motility,mucosalinjuryand/or change in intestinal microflora are the main etiologic factors. Antibiotics can cause loose watery stools by altered bacterial flora or bloody stools secondary to Clostridium difficile overgrowth and pseudomembranous colitis (PMC). Stopping the offending agent is often enough. If suspicion of PMC is presentthenstoolfor toxinassayand sigmoidoscopyis requiredfor confirmation. Metronidazole or oral vancomycin is the drug of choice for PMC.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

IBDis a chronic inflammatory disease of theGI tract and is of two main types, Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. In -10%casesthefindingsarenonspecificandsubjectscannot be classified into one of the above two groups. These cases are labelled asindeterminate colitis. Nearly 25%of all IBD presentsinthepediatricagegroup.Worldwidetheincidence ofIBDisincreasinginchildrenwithincreaseinrecentreports of bothulcerative colitis and Crohn disease from India. The averageageofpresentationinchildrenis-10-11yr.Genetics isaveryimportantriskfactorforIBDandupto30%patients

may have a family member with IBD.

Clinical features Children with ulcerative colitis present with diarrhea and rectal bleeding which raises alarm and

leads to early workup and diagnosis. In Crohn disease abdominal pain, diarrhea and growth failure are the predominant complaints. The classical triad of Crohn disease, i.e. pain, diarrhea and weight loss is seen in only 25% cases. Fever, fatigue and anorexia are present in 25-50% cases. The absence of blood in stools and non specific complaints are responsible for delay in diagnosis of Crohn disease in children.

Extraintestinal manifestations are seen in 25-30% chil dren with IBD. They can precede, follow or occur concur rently with the intestinal disease and may be related/ unrelated to activity of the intestinal disease. Arthralgia/ arthritisismostcommonextraintestinalmanifestationseen in 15-17% cases. Uveitis, erythema nodosum and scleros ingcholangitisaretheotherextra-intestinalmanifestations. Disease distribution Ulcerativecolitisisclassifiedasdistal colitis (proctitis/proctosigmoiditis), left side colitis (up to splenic flexure) and pancolitis with majority of children havingpancolitis. Majority of patients with Crohndisease (50-70%) have ileocolonic disease, with isolated colonic involvement in 10-20% and small bowel in 10-15% patients. Upper GIinvolvementis presentin30-40% cases and perianal diseasein20-25%cases. Crohndiseaseisalso classified as predominantly inflammatory, fistulizing or stricturing disease based on the clinical features.

As themanagementandprognosisof Crohndisease and ulcerative colitis is different, so a correct diagnosis is essential. Table 11.17 lists the maindifferentiatingfeatures between ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease.

Diagnosis The initial evaluation of a child withsuspected IBD includes a detailed clinical, family and treatment history. A complete examination with growth charting, perianal and rectal examination for fistulae, tags and fissures is essential. Simple lab tests like hemogram, ESR, C reactive protein, total protein, serum albumin and stool for occult blood helps in screening forIBO and confirming presence of bowel inflammation.

According to the recommendations of the IBD working group, upper GI endoscopy with biopsy, colonoscopy

|

Table 11.17: Differentiation between Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis |

|

|

Crohn disease |

Ulcerative colitis |

Distribution |

Entire gastrointestinal tract |

Colon only |

|

Discontinuous lesions |

Continuous involvement |

Bloody diarrhea |

Less common |

Common |

Abdominal pain |

Common |

Less common |

Growth failure |

Common |

Less common |

Perianal disease |

Abscess; fistulae |

Absent |

Serology |

Anti sacchromyces cerevisae antibody |

Perinuclear anti neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody |

|

(ASCA) positive |

(p-ANCA) positive |

Endoscopy |

Deep irregular serpigenous or aphthous |

Granularity, loss of vascular pattern, friability and |

|

ulcers with normal intervening mucosa |

diffuse ulceration |

|

(skip lesions) |

|

Histopathology |

Transmural inflammation with non |

Mucosa! disease with cryptitis, crypt distortion, crypt |

|

caseating granuloma |

abscess and goblet cell depletion |